- Atopic dermatitis

-

Atopic dermatitis Classification and external resources

Atopic dermatitisICD-10 L20 ICD-9 691.8 OMIM 603165 eMedicine emerg/130 derm/38 ped/2567 oph/479 MeSH D003876 Atopic dermatitis (AD, a type of eczema) is an inflammatory, chronically relapsing, non-contagious and pruritic skin disorder.[1] It has been given names like "prurigo Besnier," "neurodermitis," "endogenous eczema," "flexural eczema," "infantile eczema," and "prurigo diathésique".[2]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

The skin of a patient with atopic dermatitis reacts abnormally and easily to irritants, food, and environmental allergens and becomes red, flaky and very itchy. It also becomes vulnerable to surface infections caused by bacteria. The skin on the flexural surfaces of the joints (for example inner sides of elbows and knees) are the most commonly affected regions in people.

Atopic dermatitis often occurs together with other atopic diseases like hay fever, asthma and allergic conjunctivitis. It is a familial and chronic disease and its symptoms can increase or disappear over time. Atopic dermatitis in older children and adults is often confused with psoriasis. Atopic dermatitis afflicts humans, particularly young children; it is also a well-characterized disease in domestic dogs.

Although there is no cure for atopic eczema, and its cause is not well understood, it can be treated very effectively in the short term through a combination of prevention (learning what triggers the allergic reactions) and drug therapy.

Atopic dermatitis most often begins in childhood before age 5 and may persist into adulthood. For some, it flares periodically and then subsides for a time, even up to several years.[3] Yet, it is estimated that 75% of the cases of atopic dermatitis improve by the time children reach adolescence, whereas 25% continue to have difficulties with the condition through adulthood.[4]

Although atopic dermatitis can theoretically affect any part of the body, it tends to be more frequent on the hands and feet, on the ankles, wrists, face, neck and upper chest. Atopic dermatitis can also affect the skin around the eyes, including the eyelids.[5]

In most patients, the usual symptoms that occur with this type of dermatitis are aggravated by a Staphylococcus aureus infection, dry skin, stress, low humidity and sweating, dust or sand or cigarette smoke. Also, the condition can be worsened by having long and hot baths or showers, solvents, cleaners or detergents and wool fabrics or clothing.

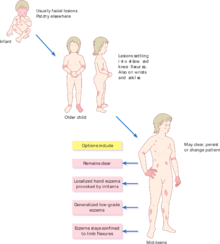

Atopic dermatitis is also known as infantile eczema, when it occurs in infants. Infantile eczema may continue into childhood and adolescence and it often involves an oozing, crusting rash mainly on the scalp and face, although it can occur anywhere on the body.[6] The appearance of the rash tends to modify, becoming dryer in childhood and then scaly or thickened in adolescence while the itching is persistent.

Approximately 50% of the patients who develop the condition display symptoms before the age of 1, and 80% display symptoms within the first 5 years of life.[4]

Symptoms may vary from person to person but they are usually present as a red, inflamed, and itchy rash and can quickly develop into raised and painful bumps.[7] The first sign of atopic dermatitis is the red to brownish-gray colored patches that are usually very itchy. Itching may become more intense during the night. The skin may present small and raised bumps which may be crusting or oozing if scratched, which will also worsen the itch. The skin tends to be more sensitive and may thicken, crack or scale.

When appearing in the area next to the eyes, scratching can cause redness and swelling around them and sometimes, rubbing or scratching in this area causes patchy loss of eyebrow hair and eyelashes.[3]

The symptoms of atopic dermatitis vary with the age of the patients. Usually, in infants, the condition causes red, scaly, oozy and crusty cheeks and the symptoms may also appear on their legs, neck and arms. Symptoms clear in about half of these children by the time they are 2 or 3 years old.[8] In older children, the symptoms include dry and thick, scaly skin with a very persistent itch, which is more severe than in infants. Adolescents are more likely to develop thick, leathery and dull-looking lesions on their face, neck, hands, feet, fingers or toes.

Causes

Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction

More recently, a theory involving the role of Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction has been proposed as an explanation on the physiopathology of atopic dermatitis. Changes in at least 3 groups of genes encoding structural proteins, epidermal proteases and protease inhibitors predispose to a defective epidermal barrier and increase the risk of developing atopic dermatitis. The strong association between both genetic barrier defects and environmental insults to the barrier with atopic dermatitis suggests that epidermal barrier dysfunction is a primary event in the development of this disease.[9]

Allergy

Although it is an inherited disease, eczema is primarily aggravated by contact with or intake of allergens. It can also be influenced by other factors that affects the immune system such as stress or fatigue. Atopic eczema consists of chronic inflammation; it often occurs in people with a history of allergy disorders such as asthma or hay fever. There is no certain cause of atopic dermatitis. In dogs, atopic dermatitis can be caused by or aggravated by inhaled allergens, food allergens, and flea bites; however, in humans, such relationships are not well established.

Microwave radiation

Exposure to microwave radiation from a cell phone can worsen existing allergies to house dust mite and Japanese Cryptomeria pollen.[10][11] In a randomized controlled trial, exposure to a cell phone that was actively transmitting increased allergen specific IgE production, whereas sham exposure did not.[12] The use of a microwave oven at home has been associated with an increased risk of eczema as well.[13] Mast cell activation is seen in children suffering from eczema.[14] Electrohypersensitive individuals suffer from increased levels of mast cells in their skin.[15]

Food allergy

While no cause of atopic dermatitis, food allergy is often present in atopic children, and children with food allergy often present with skin dermatitis indistinguishable from atopic dermatitis. New-onset atopic dermatitis patients at a later age or severe atopic dermatitis often warrant referral to an allergist for food allergy testing. Many dermatologists and physicians test for food allergy in their office. The test is often done as a "pin prick" or "needle prick." A drop of food extract is placed on the skin, and a small prick in the epidermis is performed. A "wheal" is produced with a positive test.

Common food allergen causing eczematous dermatitis include peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, milk, and egg. While food allergy induced eczematous dermatitis might present independent of atopic dermatitis, some children with atopic dermatitis also have concurrent food allergies.

Histamine intolerance

For a subset of people afflicted with atopic dermatitis are affected by exogenous sources of histamine,[16] meaning histamine from outside the body. About one-third (33%) of atopic eczematics significantly improve their symptoms after following a histamine-free diet. This diet excludes various foods high in histamine content including cheeses, hard cured sausages, alcohol, and other fermented foods.[16] Other histamine-free diets also exclude fish, shellfish, tomatoes, spinach, and eggplant as well. Fish is known to succumb to bacterial degradation quickly thus forming high amounts of histamine in the fish which can cause Scombroid poisoning. Certain vegetables like tomatoes, spinach and eggplant naturally contain histamine.

Histamine intolerance is related to an inability for the body to degrade the histamine. This decreased ability to breakdown histamine may be related to a deficiency in an enzyme called diamine oxidase (DAO). It is unknown whether a deficiency in DAO or another mechanism is responsible for the impaired histamine processing.

Biological

Although it is such a common disease, relatively little is understood about the underlying causes of atopic eczema.[17] While AE is associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis, the connection between the diseases has not been established.[17] Twin studies have consistently shown that the disease has a higher rate of concordance in identical as compared to fraternal twins, which also indicates that genetics plays a role in its development.[17] However, the rate of concordance between identical twins is far from 100%, and the changing frequency of the disease over time points to the environmental factors—nutrition or hygiene, for instance—that also play a role in disease susceptibility.[18]

Genomic research into the cause of multigenic diseases is still in its infancy: few genes have ever been identified that contribute to multigenic human disorders.[18] Researchers have attempted to do this in past whole-genome screens for AE and related diseases, but their results have been inconsistent. A few of the pertinent loci have been validated by replication in further studies (chromosome 2q, chromosome 6p, and chromosome 12q, for example),[19] but most have not been.

Associations with ATOD1, ATOD2, ATOD3, ATOD4, ATOD5 and ATOD6 have been identified.[20]

In a publication in Nature Genetics from April 6, 2009, Young-Ae Lee of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin and her colleagues report a strong association between atopic dermatitis and a common genetic variant, a new locus on chromosome 11, potentially associated with the gene C11orf30.[21]

Prevention

Since there is no cure for atopic eczema, treatment should mainly involve discovering the triggers of allergic reactions and learning to avoid them.

Diet

Originally controversial, the association of food allergy with atopic dermatitis has now been clearly demonstrated. Many common food allergens can trigger an allergic reaction: such as milk, nuts, cheese, tomatoes, wheat, yeast, soy, and corn. Many of these allergens are common ingredients in grocery store products (especially corn syrup, which is a sugar substitute). Specialty health food stores often carry products that do not contain common allergens.

It has also been established that about a third of people afflicted with atopic dermatitis may have histamine intolerance[16] and benefit from a histamine-free diet. Various foods commonly associated with allergies also happen have high histamine content. Foods such as cheeses, yogurt, alcohol, fish, shellfish, tomatoes, and fermented foods (soy, yeast, etc.) all have high histamine content. Other histamine foods include spinach, and eggplant, hard-cured sausages, and other processed meats. Various food additives including benzoates and food coloring have also been shown to release endogenous histamine.[22] Avoiding high histamine foods and processed foods may be beneficial in improving symptoms.

Breastfeeding has been demonstrated to help prevent the development of allergic disease, but if that is unavailable, then hydrolyzed formulas are preferred to cow's milk.[23] The use of organic dairy products by children and breastfeeding or pregnant mothers reduces the risk of atopic dermatitis in young children.[24] The avoidance of common food allergens including milk and dairy products, egg, fish, beef and peanut during pregnancy and lactation has also been shown to enhance the preventive beneficial effect of exclusive breast feeding on the incidence of atopic eczema among infants at high risk.[25]

Environment and lifestyle

Since dust is a very common allergen and irritant, adults with atopic eczema should avoid smoking, as well as the inhalation of dust in general. The dander from the fur of dogs and cats may also trigger an inflammatory response. It is a common misconception that simply removing an animal from a room will prevent an allergic reaction from occurring. A room must be completely free of animal dander in order to prevent an allergic reaction. Anger, stress, and lack of sleep are also factors that are known to aggravate eczema. Excessive heat (especially with humidity) and coldness are known to provoke outbreaks, as well as sudden and extreme temperature swings.

Allergen/irritant evasion

An allergy skin-patch or "scratch" test, given by an allergist, can often pinpoint the triggers of allergic reactions. Once the causes of the allergic reactions are discovered, the allergens should be eliminated from the diet, lifestyle, and/or environment. If the eczema is severe, it may take some time (days to weeks depending on the severity) for the body's immune system to begin to settle down after the irritants are withdrawn.

Treatment

Maintaining the skin barrier

The primary treatment involves prevention, includes avoiding or minimizing contact with (or intake of) known allergens. Once that has been established, topical treatments can be used. Topical treatments focus on reducing both the dryness and inflammation of the skin.

To combat the severe dryness associated with atopic dermatitis, a high-quality, dermatologist-approved moisturizer should be used daily. Moisturizers should not have any ingredients that may further aggravate the condition. Moisturizers are especially effective if applied 5–10 minutes after bathing. As a rule of thumb the thicker the moisturizer the better it is at retaining moisture. Petroleum jelly is considered one of the most effective moisturizers by reducing transepidermal water loss by up to 98%. [26]

Atopic dermatitis has also been linked to a ceramide deficiency. Ceramide is one of the three key lipids that comprise the skin barrier.[27] The "stratum corneum ceramide deficiency" is possibly "the putative cause of the barrier abnormality"[28] in atopic dermatitis. There are various ceramide based creams available including the prescription drug Epiceram as well as other non-prescription options like Cerave and Aveeno for Eczema.

A doctor might prescribe lotion containing sodium hyaluronate to improve skin dryness. One brand of sodium hyaluronate lotion is Hylira.[29][30]

Most commercial soaps wash away all the oils produced by the skin that normally serve to prevent drying. Using a soap substitute such as aqueous cream helps keep the skin moisturized. A non-soap cleanser can be purchased usually at a local drug store. Showers should be kept short and at a lukewarm/moderate temperature.

Prescription drugs

If moisturizers on their own don't help and the eczema is severe, a doctor may prescribe topical corticosteroid ointments, creams, or injections. Corticosteroids have traditionally been considered the most effective method of treating severe eczema. Disadvantages of using steroid creams include stretch marks and thinning of the skin. Higher-potency steroid creams must not be used on the face or other areas where the skin is naturally thin; usually a lower-potency steroid is prescribed for sensitive areas. The use of the finger tip unit may be helpful in guiding how much topical cream is required to cover different areas. If the eczema is especially severe, a doctor may prescribe prednisone or administer a shot of cortisone or triamcinolone. In some countries, over-the-counter hydrocortisone can be purchased for treatment of mild eczema.

If complications include infections (often of Staphylococcus aureus), antibiotics may be employed.

The immunosuppressants tacrolimus and pimecrolimus can be used as a topical preparation in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis instead of or in addition to traditional steroid creams. There can be unpleasant side effects in some patients such as intense stinging, itching or burning, which mostly get better after the first week of treatment.[31] However, the risk of developing skin cancer from the use of these drugs[32] (especially when combined to UV exposure, such as sunrays) was not ignored by the FDA, which issued a "black box warning."[33]

In severe cases that do not respond to other treatments, oral immunosuppressant medications are sometimes prescribed, such as ciclosporin, azothioprine and methotrexate. However, these treatments require patients to take regular blood tests as they can have significant side effects on the kidneys and liver.

Light (UV) therapy

A more novel form of treatment involves exposure to broad or narrow-band ultraviolet light. UV radiation exposure has been found to have a localized immunomodulatory effect on affected tissues and may be used to decrease the severity and frequency of flares.[34] In particular, Meduri et al. have suggested that the usage of UVA1 is more effective in treating acute flares, whereas narrow-band UVB is more effective in long-term management scenarios.[35] However, UV radiation has also been implicated in various types of skin cancer,[36] and thus UV treatment is not without risk.

If ultraviolet light therapy is employed, initial exposure should be no longer than 5–10 minutes, depending on skin type. UV therapy should only be moderate, and special care should be taken to avoid sunburn (sunburn will only aggravate the eczema). It does not necessarily have to be administered in a hospital; it can be done at a tanning salon or in natural sunlight, as long as it's done under the direction and supervision of a dermatologist.[37]

Alternative treatments

Four small and low-quality randomized clinical trials found beneficial effects from a Traditional Chinese medicine herbal formulation called Zemaphyte, which is no longer manufactured.[38] A randomized clinical trial published in 2007 found that another Chinese herbal formulation increased quality of life and reduced topical corticosteroid use.[39]

Alternative medicines may (illegally) contain corticosteroids, which are standard treatments for atopic dermatitis, raising a question of whether these illicit substances cause the effects;[40] however, a 2006 study did not find corticosteroids in a PentaHerbs concoction that had shown beneficial effects.[41]

A study in April 2009 showed that bathing in a dilute household bleach solution (1/2 cup or 120 ml of ordinary household chlorine bleach (sodium hypochlorite) to a bathtub full of water) in combination with nasal application of mupirocin can be beneficial in patients with clinical signs of secondary bacterial infections.[42] It is believed that the antibacterial effect of these agents prevents the skin's colonization by staphylococcus aureus which can cause infections in an existing rash when the skin is broken by scratching; this in turn increases the itching, leading to more scratching and inflammation. If a bath is not available, swab onto reddened skin a dilute solution of 4.5 ml household bleach in 750 ml water. The skin must be moisturised with the patient's preferred moisturiser or oil after the antibacterial swabbing or bath.

Future research

It was less than ten years ago that the researchers discovered the first mouse model to spontaneously developed AE-like lesions, the inbred NC/Nga mouse.[43] These models have been used for tests that would have been impossible in humans, like the administration of Mycobacterium vaccae for the possible prevention of AE-like lesions.[44]

Trials are being carried out at the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council in the UK to see if applying a naturally occurring molecule on the skin will improve the barrier function. The skin of people who suffer from Atopic Dematitis often lacks an efficient barrier making their skin more susceptible to microbial invasions. The trial is expected to end in Jan 2011 [45]

Epidemiology

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, many mucosal inflammatory disorders have become dramatically more common; atopic eczema (AE) is a classic example of such a disease. It now affects 10–20% of children and 1–3% of adults in industrialized countries, and its prevalence in the United States alone has nearly tripled in the past thirty to forty years.[46]

Atopic dermatitis is a common disease which tends to affect both males and females in the same proportion. It is estimated that this condition accounts for about 20% of all dermatologic referrals. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis is however quite difficult to establish since the diagnostic criteria are not applied universally and are not standard, but it is thought to vary roughly between 10% and 30%. Most of the population-based studies report that at least 80% of the atopic dermatitis populations have mild eczema.[47]

Atopic dermatitis occurs most often in infants and children, and its onset decreases substantially with age, and it is highly unlikely to develop in patients who are older than 30 years.[48] The condition appears to primarily affect individuals who live in urban areas and in climates with low humidity. However, specialists claim that there is a genetic factor which may play an important role in the development of atopic dermatitis.

See also

References

- ^ De Benedetto, A; Agnihothri, R; McGirt, LY; Bankova, LG; Beck, LA (2009). "Atopic dermatitis: a disease caused by innate immune defects?". The Journal of investigative dermatology 129 (1): 14–30. doi:10.1038/jid.2008.259. PMID 19078985.

- ^ Abels, C; Proksch, E (2006). "Therapy of atopic dermatitis". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete 57 (8): 711–725. doi:10.1007/s00105-006-1176-x. PMID 16816954.

- ^ a b "Atopic dermatitis (eczema)". http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/eczema/ds00986/dsection=symptoms. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ a b "Atopic Dermatitis – Symptoms, Diagnosis". http://www.dermatologychannel.net/dermatitis/atopic-dermatitis-symptoms.shtml. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Factors that worsen atopic dermatitis". http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/eczema/ds00986/dsection=symptoms. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Infantile eczema". http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/eczema/ds00986/dsection=symptoms. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Dermatitis Atopic Eczema". http://www.dermatitisatopic.net/. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Signs and Symptoms". http://www.dermatologychannel.net/dermatitis/atopic-dermatitis-symptoms.shtml. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Cork MJ, et al. Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. J Inv Dermatol 2009. 129:1892-1908

- ^ Kimata, H (2002). "Enhancement of allergic skin wheal responses by microwave radiation from mobile phones in patients with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome". International archives of allergy and immunology 129 (4): 348–350. doi:10.1159/000067592. PMID 12483040.

- ^ Kimata, H (2003). "Enhancement of allergic skin wheal responses in patients with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome by playing video games or by a frequently ringing mobile phone". European journal of clinical investigation 33 (6): 513–517. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01177.x. PMID 12795649.

- ^ Kimata, H. (2005). "Microwave radiation from cellular phones increases allergen-specific IgE production". Allergy 60 (6): 838–839. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00802.x. PMID 15876318.

- ^ Wang, IJ; Guo, YL; Weng, HJ; Hsieh, WS; Chuang, YL; Lin, SJ; Chen, PC (2007). "Environmental risk factors for early infantile atopic dermatitis". Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 18 (5): 441–447. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00550.x. PMID 17617812.

- ^ Øymar, K; Aksnes, L (2004). "Urinary 9alpha,11beta-prostaglandin F(2) in children with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome: an indicator of mast cell activation?". Acta dermato-venereologica 84 (5): 359–362. doi:10.1080/00015550410035515. PMID 15370701.

- ^ Johansson, Olle (2006). "Electrohypersensitivity: State-of-the-Art of a Functional Impairment". Electromagnetic Biology and Medicine 25 (4): 245–258. doi:10.1080/15368370601044150. PMID 17178584. http://adante.vingar.se/electrohypersensitivity1.pdf.

- ^ a b c . pp. 52–56. doi:10.2340/00015555-0565.

- ^ a b c Kluken, H.; Wienker, T.; Bieber, T. (2003). "Atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome – a genetically complex disease. New advances in discovering the genetic contribution". Allergy 58 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.02162.x. PMID 12580800.

- ^ a b Schreiber, Stefan; Rosenstiel, Philip; Albrecht, Mario; Hampe, Jochen; Krawczak, Michael (2005). "Genetics of Crohn disease, an archetypal inflammatory barrier disease". Nature Reviews Genetics 6 (5): 376–388. doi:10.1038/nrg1607. PMID 15861209.

- ^ Palmer, L. J.; Cookson, WO (2000). "Genomic Approaches to Understanding Asthma". Genome Research 10 (9): 1280–1287. doi:10.1101/gr.143400. PMID 10984446.

- ^ "OMIM – DERMATITIS, ATOPIC". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=603165. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Esparza-Gordillo, Jorge; Weidinger, Stephan; F lster-Holst, Regina; Bauerfeind, Anja; Ruschendorf, Franz; Patone, Giannino; Rohde, Klaus; Marenholz, Ingo et al. (2009). "A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis". Nature Genetics 41 (5): 596–601. doi:10.1038/ng.347. PMID 19349984.

- ^ Histamine Restricted Diet—ICUS – International Chronic Urticaria Society. Urticaria.thunderworksinc.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-05.

- ^ Odijk, J.; Kull, I.; Borres, M. P.; Brandtzaeg, P.; Edberg, U.; Hanson, L. A.; Host, A.; Kuitunen, M. et al. (2003). "Breastfeeding and allergic disease: a multidisciplinary review of the literature (1966–2001) on the mode of early feeding in infancy and its impact on later atopic manifestations". Allergy 58 (9): 833–843. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00264.x. PMID 12911410.

- ^ KOALA Birth Cohort Study, University of Maastricht, the Netherlands (Dutch language only)

- ^ Chandra, RK; Puri, S; Suraiya, C; Cheema, PS (1986). "Influence of maternal food antigen avoidance during pregnancy and lactation on incidence of atopic eczema in infants". Clinical allergy 16 (6): 563–569. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1986.tb01995.x. PMID 3791630.

- ^ Petroleum Jelly: Facts and Myths. Articlesbase.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-05.

- ^ Ceramide Barrier Repair

- ^ Chamlin, SL; Kao, J; Frieden, IJ; Sheu, MY; Fowler, AJ; Fluhr, JW; Williams, ML; Elias, PM (2002). "Ceramide-dominant barrier repair lipids alleviate childhood atopic dermatitis: changes in barrier function provide a sensitive indicator of disease activity". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 47 (2): 198–208. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.124617. PMID 12140465. Lay summary – Medscape (August 12, 2002).

- ^ Hylira Gel Facts and Comparisons at. Drugs.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-05.

- ^ "Hylira Gel Facts and Comparisons at". Drugs.com. 2010-05-05. http://www.drugs.com/cdi/hylira-lotion.html. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ Jasek, W, ed (2007) (in German). Austria-Codex (62 ed.). Vienna. pp. 2720, 6770. ISBN 3-85200-181-4.

- ^ Wooltorton, E. (2005). "Eczema drugs tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel): cancer concerns". Canadian Medical Association Journal 172 (9): 1179–1180. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050373. PMC 557066. PMID 15817641. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=557066.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (United States) (2005-03-10). "Safety information on Protopic (tacrolimus), Elidel (pimecrolimus)". http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm152565.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ Beattie, P.E.; Finlan, L.E.; Kernohan, N.M.; Thomson, G.; Hupp, T.R.; Ibbotson, S.H. (2005). "The effect of ultraviolet (UV) A1, UVB and solar-simulated radiation on p53 activation and p21Waf1/Cip1". British Journal of Dermatology 152 (5): 1001–1008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06557.x. PMID 15888160.

- ^ Meduri, N. Bhavani; Vandergriff, Travis; Rasmussen, Heather; Jacobe, Heidi (2007). "Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine 23 (4): 106–112. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00291.x.

- ^ Jans, J.; Garinis, G. A.; Schul, W.; Van Oudenaren, A.; Moorhouse, M.; Smid, M.; Sert, Y.-G.; Van Der Velde, A. et al. (2006). "Differential Role of Basal Keratinocytes in UV-Induced Immunosuppression and Skin Cancer". Molecular and Cellular Biology 26 (22): 8515–8526. doi:10.1128/MCB.00807-06. PMC 1636796. PMID 16966369. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1636796.

- ^ Scheinfeld, NS; Tutrone, WD; Weinberg, JM; Deleo, VA (2003). "Phototherapy of atopic dermatitis". Clinics in dermatology 21 (3): 241–248. doi:10.1016/S0738-081X(02)00364-4. PMID 12781441.

- ^ Zhang, W; Leonard, T; Bath-Hextall, F; Chambers, CA; Lee, C; Humphreys, R; Williams, HC; Zhang, Weiya (2004). "Chinese herbal medicine for atopic eczema". In Zhang, Weiya. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002291.pub3.

- ^ Hon, K.L.E.; Leung, T.F.; Ng, P.C.; Lam, M.C.A.; Kam, W.Y.C.; Wong, K.Y.; Lee, K.C.K.; Sung, Y.T. et al. (2007). "Efficacy and tolerability of a Chinese herbal medicine concoction for treatment of atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". British Journal of Dermatology 157 (2): 357–363. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07941.x. PMID 17501956.

- ^ Ramsay, H M; Goddard, W; Gill, S; Moss, C (2003). "Herbal creams used for atopic eczema in Birmingham, UK illegally contain potent corticosteroids". Archives of Disease in Childhood 88 (12): 1056–1057. doi:10.1136/adc.88.12.1056. PMC 1719403. PMID 14670768. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1719403.

- ^ Hon, Kam-Lun E.; Lee, Vivian W. Y.; Leung, Ting-Fan; Lee, Kenneth K. C.; Chan, Andrew K. W.; Fok, Tai-Fai; Leung, Ping-Chung (November 2006). "Corticosteroids are not present in a traditional Chinese medicine formulation for atopic dermatitis in children". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 35 (11): 759–63. PMID 17160188. http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/35VolNo11Nov2006/V35N11p759.pdf.

- ^ Huang, J. T.; Abrams, M.; Tlougan, B.; Rademaker, A.; Paller, A. S. (2009). "Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Atopic Dermatitis Decreases Disease Severity". Pediatrics 123 (5): e808–e814. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2217. PMID 19403473.

- ^ Gutermuth, Jan; Ollert, Markus; Ring, Johannes; Behrendt, Heidrun; Jakob, Thilo (2004). "Mouse Models of Atopic Eczema Critically Evaluated". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 135 (3): 262–276. doi:10.1159/000082099. PMID 15542938.

- ^ Arkwright, Peter D.; Fujisawa, Chie; Tanaka, Akane; Matsuda, Hiroshi (2005). "Mycobacterium vaccae Reduces Scratching Behavior but not the Rash in NC Mice with Eczema: A Randomized, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial". Journal of Investigative Dermatology 124 (1): 140–143. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23561.x. PMID 15654967.

- ^ ISRCTN97515110 – Investigating whether topical application of a non toxic molecule improves epidermal pH and barrier function in atopic dermatitis

- ^ Saito, Hirohisa (2005). "Much Atopy about the Skin: Genome-Wide Molecular Analysis of Atopic Eczema". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 137 (4): 319–325. doi:10.1159/000086464. PMID 15970641.

- ^ "Eczema". http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/451667_2. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "How common is atopic dermatitis?". http://www.medicinenet.com/atopic_dermatitis/page2.htm#3howcommon. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

External links

- NEA All About Atopic Dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis picture page at Dermnet

- NIH Handout on Health: Atopic Dermatitis

- Staphy.com a site about atopic eczema

- DermAtlas 9

Health science - Medicine - Allergic conditions Respiratory system Allergic rhinitis · Asthma · Hypersensitivity pneumonitis · Eosinophilic pneumonia · Churg-Strauss syndrome · Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis · Farmer's lung · Laboratory animal allergySkin Angioedema · Urticaria · Atopic dermatitis · Allergic contact dermatitis · Hypersensitivity vasculitisBlood and immune system Circulatory system Digestive system Nervous system Eosinophilic meningitisGenitourinary system Other conditions Dermatitis and eczema (L20–L30, 690–693,698) Atopic dermatitis Besnier's prurigoSeborrheic dermatitis Pityriasis simplex capillitii · Cradle capContact dermatitis

(allergic, irritant)other: Abietic acid dermatitis · Diaper rash · Airbag dermatitis · Baboon syndrome · Contact stomatitis · Protein contact dermatitisEczema Autoimmune estrogen dermatitis · Autoimmune progesterone dermatitisBreast eczema · Ear eczema · Eyelid dermatitis · Hand eczema (Chronic vesiculobullous hand eczema, Hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis)Autosensitization dermatitis/Id reaction (Candidid, Dermatophytid, Molluscum dermatitis) · Circumostomy eczema · Dyshidrosis · Juvenile plantar dermatosis · Nummular eczema · Nutritional deficiency eczema · Sulzberger–Garbe syndrome · Xerotic eczemaPruritus/Itch/

PrurigoDrug-induced pruritus (Hydroxyethyl starch-induced pruritus) · Senile pruritus · Aquagenic pruritus (Aquadynia)Adult blaschkitis · due to liver disease (Biliary pruritus · Cholestatic pruritus) · Prion pruritus · Prurigo pigmentosa · Prurigo simplex · Puncta pruritica · Uremic pruritusOther/ungrouped substances taken internally: Bromoderma · Fixed drug reactionImmune disorders: hypersensitivity and autoimmune diseases (279.5–6) Type I/allergy/atopy

(IgE)ForeignAtopic dermatitis · Allergic urticaria · Hay fever · Allergic asthma · Anaphylaxis · Food allergy (Milk, Egg, Peanut, Tree nut, Seafood, Soy, Wheat), Penicillin allergyAutoimmunenoneType II/ADCC

(IgM, IgG)ForeignAutoimmuneAutoimmune hemolytic anemia · Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura · Bullous pemphigoid · Pemphigus vulgaris · Rheumatic fever · Goodpasture's syndromeType III

(Immune complex)ForeignHenoch–Schönlein purpura · Hypersensitivity vasculitis · Reactive arthritis · Rheumatoid arthritis · Farmer's lung · Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis · Serum sickness · Arthus reactionAutoimmuneType IV/cell-mediated

(T-cells)ForeignAllergic contact dermatitis · Mantoux testAutoimmuneUnknown/

multipleForeignAutoimmuneSjögren's syndrome · Autoimmune hepatitis · Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS1, APS2) · Autoimmune adrenalitis · Systemic autoimmune diseaseCategories:- Type 1 hypersensitivity

- Atopic dermatitis

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.