- Transplant rejection

-

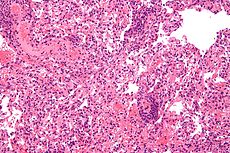

Transplant rejection Classification and external resources

Micrograph showing lung transplant rejection. Lung biopsy. H&E stain.ICD-10 T86 MedlinePlus 000815 MeSH D006084 Transplant rejection occurs when transplanted tissue is rejected by the recipient's immune system, which destroys the transplanted tissue. Transplant rejection can be lessened by determining the molecular similitude between donor and recipient and by use of immunosuppressant drugs after transplant.[1]

Contents

Pretransplant rejection prevention

Main article: HistocompatibilityThe first successful organ transplant, performed in 1954 by Joseph Murray, involved identical twins, and so no rejection was observed. Otherwise, the number of mismatched gene variants, namely alleles, encoding cell surface molecules called major histocompatibility complex (MHC), classes I and II, correlate with the rapidity and severity of transplant rejection. In humans MHC is also called human leukocyte antigen (HLA).

Though cytotoxic-crossmatch assay can predict rejection mediated by cellular immunity, genetic-expression tests specific to the organ type to be transplanted, for instance AlloMap Molecular Expression Testing, have a high negative predictive value. Transplanting only ABO-compatible grafts, matching blood groups between donor and recipient, helps prevent rejection mediated by humoral immunity.

Immunologic rejection mechanisms

Rejection is an adaptive immune response via cellular immunity (mediated by killer T cells inducing apoptosis of target cells) as well as humoral immunity (mediated by activated B cells secreting antibody molecules), though the action is joined by components of innate immune response (phagocytes and soluble immune proteins). Different types of transplanted tissues tend to favor different balances of rejection mechanisms.

Humoral immunity

A recipient's preexisting adaptive antibody molecules, developed through an earlier primary exposure that primed adaptive immunity—which matured before the transplant occurring as secondary exposure—the specific antibody crossreacts with donor tissue, as typical after earlier mismatching among A/B/O blood types. Components of innate immunity, then, namely soluble immune proteins called complement and innate immune cells called phagocytes, inflame and destroy the transplanted tissue.

An antibody molecule, secreted by an activated B cell, then called plasma cell, is a soluble immunoglobulin (Ig) whose constituent unit is configured alike the letter Y: the two arms are the Fab regions and the single stalk is the Fc region. Each Fab tip is the paratope, which ligates (binds) a cognate (matching) molecular sequence as well as its 3D shape (its conformation), altogether called epitope, within a specific antigen.

When the paratope of Ig class gamma (IgG) ligates its epitope, IgG's Fc region conformationally shifts and can host a complement protein, initiating the complement cascade that terminates by punching a hole in a cell membrane, and with many holes so punched, the cell ruptures as fluid rushes in. Molecular motifs of necrotic cell debris are recognized as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), then, when ligating Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on membranes of innate immune cells, which phagocytes are thereby activated to secrete proinflammatory cytokines recruiting more phagogytes to traffic to the area by sensing the concentration gradient of the secreted cytokines (chemotaxis). IgG's Fc region also enables opsonization by a phagocyte—such as neutrophils in blood and macrophages in tissues—which attains improved uptake of cell debris and tissue by seizing the IgG molecule's Fc stalk.

Cellular immunity

Transplanted organs are often acquired from a cadaver—usually a host who had succumbed to trauma—and the tissues had already sustained ischemia or inflammation. Dendritic cells (DCs) of the donor tissue migrate to the recipient's peripheral lymphoid tissue—lymphoid follicles and lymph nodes—and present the donor's self peptides to the recipient's naive helper T cells. Primed toward these allogeneic HLA peptides, the helper T cells effect immunomemory at either 1) the donor's self peptides, 2) the allogeneic HLA molecules, or 3) both.

The primed helper T cells establish alloreactive killer T cells whose CD8 receptors dock to the transplanted tissue's MHC class I molecules presenting self peptides, whereupon the T cell receptors (TCRs) of the killer T cells recognize their epitope—self peptide now coupled within MHC class I molecules—and transduce signals into the target cell prompting its programmed cell death by apoptosis.

When the CD4 receptors of helper T cells dock to their hosts, MHC class II molecules, expressed by select cells, their own TCRs—the paratope—might recognize their matching epitope being presented, and thereupon approximate the secretion of cytokines that had prevailed during their priming event, an aggressively proinflammatory balance of cytokines.

Tissue Mechanism Blood Antibodies (isohaemagglutinins) Kidney Antibodies, cell-mediated immunity (CMI) Heart Antibodies, CMI Skin CMI Bonemarrow CMI Cornea Usually accepted unless vascularised: CMI Medical categories of rejection

Hyperacute rejection

Initiated by preexisting humoral immunity, hyperacute rejection manifests within minutes after transplant, and if tissue is left implanted brins systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Of high risk in kidney transplants is rapid clumping, namely agglutination, of red blood cells (RBCs or erythrocytes), as an antibody molecule binds multiple target cells at once.

Acute rejection

Developing with formation of cellular immunity, acute rejection occurs to some degree in all transplants, except between identical twins, unless immunosuppression is achieved (usually through drugs). Acute rejection begins as early as one week after transplant, the risk highest in the first three months, though it can occur months to years later. Highly vascular tissues such as kidney or liver often host the earliest signs—particularly at endothelial cells lining blood vessels—though it eventually occurs in roughly 10 to 30% of kidney transplants, and 50 to 60% of liver transplants. A single episode of acute rejection can be recognized and promptly treated, usually preventing organ failure, but recurrent episodes lead to chronic rejection.

Chronic rejection

The term chronic rejection initially described long-term loss of function in transplanted organs via fibrosis of the transplanted tissue's blood vessels. This is now chronic allograft vasculopathy, however, leaving chronic rejection referring to rejection due to more patent aspects of immunity.

Chronic rejection explains long-term morbidity in most lung-transplant recipients,[2][3] the median survival roughly 4.7 years, about half the span versus other major organ transplants.[4] In histopathology the condition is bronchiolitis obliterans, which clinically presents as progressive airflow obstruction, often involving dyspnea and coughing, and the patient eventually succumbs to pulmonary insufficiency or secondary acute infection.

Airflow obstruction not ascribable to other cause is labeled bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), confirmed by a persistent drop—three or more weeks—in forced expiratory volume (FEV1) by at least 20%.[5] BOS is seen in over 50% of lung-transplant recipients by 5 years, and in over 80% by ten years. First noted is infiltration by lymphocytes, followed by epithelial cell injury, then inflammatory lesions and recruitment of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, which proliferate and secrete proteins forming scar tissue.[6] Generally thought unpredictable, BOS progression varies widely: lung function may suddenly fall but stabilize for years, or rapidly progress to death within a few months. Risk factors include prior acute rejection episodes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, acute infections, particular age groups, HLA mis-matching, lymphocytic bronchiolitis, and graft dysfunction (e.g., airway ischemia).[7]

Rejection detection

Diagnosis of acute rejection relies on clinical data—patient signs and symptoms—but also calls on laboratory data such as tissue biopsy. The laboratory pathologist generally seeks three main histological signs: (1) infiltrating T cells, perhaps accompanied by infiltrating eosinophils, plasma cells, and neutrophils, particularly in telltale ratios, (2) structural compromise of tissue anatomy, varying by tissue type transplanted, and (3) injury to blood vessels. Tissue biopsy is restricted, however, by sampling limitations and risks complications of the invasive procedure. Cellular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of immune cells radiolabeled in vivo might offer noninvasive testing.[8]

Rejection treatment

Hyperacute rejection minifests severely and within minutes, and so treatment is immediate: removal of the tissue. Chronic rejection is generally considered irreversible and poorly amenable to treatment—only retransplant generally indicated if feasible—though inhaled ciclosporin is being investigated to delay or prevent chronic rejection of lung transplants. Acute rejection is treated with one or multiple of a few strategies.

Immunosuppressive therapy

A short course of high-dose corticosteroids can be applied, and repeated. Triple therapy adds a calcineurin inhibitor and an anti-proliferative agent. Where calcineurin inhibitors or steroids are contraindicated, mTOR inhibitors are used.

Immunosuppressive drugs:

- Corticosteroids

- Prednisolone

- Hydrocortisone

- Calcineurin inhibitors

- Anti-proliferatives

- mTOR inhibitors

Antibody-based treatments

Antibody specific to select immune components can be added to immunosuppressive therapy. The monoclonal anti-T cell antibody OKT3, once used to prevent rejection, and still occasionally used to treat severe acute rejection, has fallen into disfavor, as it commonly brings severe cytokine release syndrome and late post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. (OKT3 is available in the United Kingdom for named-patient use only.)

Antibody drugs:

- Monoclonal anti-IL-2Rα receptor antibodies

- Polyclonal anti-T-cell antibodies

- Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG)

- Anti-lymphocyte globulin (ALG)

- Monoclonal anti-CD20 antibodies

Blood transfer

Cases refractory to immunosuppressive or antibody therapy are sometimes given blood transfusions—removing antibody molecues specific to the transplanted tissue.

Marrow transplant

Bone marrow transplant can replace the transplant recipient's immune system with the donor's, and the recipient accepts the new organ without rejection. The marrow — reservoir of replenishing blood cells — must be of the individual who donated the organ (or an identical twin or a clone). There is a risk of graft versus host disease (GVHD), however, whereby mature lymphocytes entering with marrow recognize the new host tissues as foreign and destroy them.

References

- Gorman, Rachael Moeller. "The Transplant Trick," Proto, Spring 2009.

- ^ Frohn C, Fricke L, Puchta JC, Kirchner H. "The effect of HLA-C matching on acute renal transplant rejection". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 16:355-60.

- ^ Pediatr Transplant. 2005 Feb;9(1):84-93

- ^ Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003 Nov;47:57s-64s

- ^ http://www.OPTN.org

- ^ Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun 1;175(11):1192-8

- ^ Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:444-49

- ^ Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(1):108-21

- ^ Hitchens TK, Ye Q, Eytan DF, Janjic JM, Ahrens ET, Ho C, "19F MRI detection of acute allograft rejection with in vivo perfluorocarbon labeling of immune cells". Magnetic Resonance Med. 2011 Apr;65(4):114-53.

External links

Organ transplantation Types Organs and tissues Medical grafting Organ donation Conditions Related topics Biomedical tissue · Edmonton protocol · Eye bank · Immunosuppressive drugs · Lung allocation score · Machine perfusion · Total body irradiation · Transplantation medicineOrganizations Countries Organ transplantation in the People's Republic of China · Organ transplantation in Israel · Organ transplantation in Japan · Organ theft in Kosovo · Organ transplantation in different countries · Gurgaon kidney scandalPeople Christiaan Barnard · Alexis Carrel · Jean-Michel Dubernard · Donna Mansell · Norman Shumway · Michael Woodruff · List of notable organ transplant donors and recipientsCategories:- Immune system disorders

- Transplantation medicine

- Corticosteroids

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.