- Persecution of Christians

-

This article is about acts committed against Christians because of their faith. For negative attitudes towards Christians, see Anti-Christian sentiment.

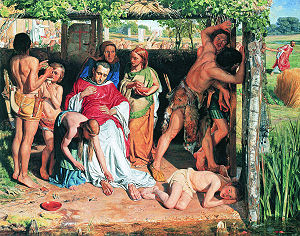

A Christian Dirce, by Henryk Siemiradzki. A Christian woman is martyred under Nero in this re-enactment of the myth of Dirce (painting by Henryk Siemiradzki, 1897, National Museum, Warsaw).

A Christian Dirce, by Henryk Siemiradzki. A Christian woman is martyred under Nero in this re-enactment of the myth of Dirce (painting by Henryk Siemiradzki, 1897, National Museum, Warsaw).

Persecution of Christians as a consequence of professing their faith can be traced both historically and in the current era. Early Christians were persecuted for their faith, at the hands of both Jews from whose religion Christianity arose, and the Roman Empire which controlled much of the land early Christianity was distributed across. This continued from the 1st century until the early 4th, when the religion was legalized by Constantine I. Michael Gaddis wrote:

The Christian experience of violence during the pagan persecutions shaped the ideologies and practices that drove further religious conflicts over the course of the fourth and fifth centuries... The formative experience of martyrdom and persecution determined the ways in which later Christians would both use and experience violence under the Christian empire. Discourses of martyrdom and persecution formed the symbolic language through which Christians represented, justified, or denounced the use of violence."[1]

Christian missionaries as well as the neophytes that they converted to Christianity have been the target of persecution, many times to the point of being martyred for their faith. There is also a history of individual Christian denominations suffering persecution at the hands of other Christians under the charge of heresy, particularly during the 16th century Protestant Reformation.

In the 20th century, Christians have been persecuted by Muslim and Hindu groups inter alia, and by atheistic states such as the USSR and North Korea.

Currently (as of 2010), as estimated by the Christian missionary organisation Open Doors UK, an estimated 100 million Christians face persecution, particularly in North Korea, Iran and Saudi Arabia.[2] A recent study, cited by the Vatican, reported that 75 out of every 100 people killed due to religious hatred are Christian.[3][4]

Antiquity

Persecution of Christians in the New Testament

Main article: Persecution of Christians in the New TestamentEarly Christianity began as a sect among early Jews and according to the New Testament account, Pharisees, including Paul of Tarsus prior to his conversion to Christianity, persecuted early Christians. The early Christians preached a Messiah which did not conform to the expectations of the time.[5] However, feeling that he was presaged in Isaiah's Suffering Servant and in all of Jewish scripture, Christians had been hopeful that their countrymen would accept their vision of a New Israel.[5] Despite many individual conversions, a fierce opposition was found in their countrymen.[5]

The Crucifixion of St. Peter by Caravaggio

The Crucifixion of St. Peter by Caravaggio

Dissention began almost immediately with the teachings of Stephen at Jerusalem (unorthodox by contemporaneous Jewish standards), and never ceased entirely while the city remained.[5] A year after the crucifixion of Jesus, Stephen was stoned for his alleged transgression of orthodoxy,[6] with Saul (who later converted and was renamed Paul) heartily agreeing.

In 41 AD, when Agrippa I, who already possessed the territory of Antipas and Phillip, obtained the power of procurator in Judea, hence re-forming the Kingdom of Herod, he was reportedly eager to endear himself to his Jewish subjects and continued the persecution in which James the lesser lost his life, Peter narrowly escaped and the rest of the apostles took flight.[5]

After Agrippa's death, the Roman procuratorship resumed and those leaders maintained a neutral peace, until the procurator Festus died and the high priest Annas II took advantage of the power vacuum to attack the Church and executed James the greater, then leader of Jerusalem's Christians.[5] The New Testament states that Paul was himself imprisoned on several occasions by Roman authorities, stoned by Pharisees and left for dead on one occasion, and was eventually taken as a prisoner to Rome. Peter and other early Christians were also imprisoned, beaten and harassed. A Jewish revolt, spurred by the Roman killing of 3,000 Jews, led to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the end of sacrificial Judaism, and the disempowering of the Jewish persecutors; the Christian community, meanwhile, having fled to safety in the already pacified region of Pella.[5] The early persecution by the Jews is estimated to have a death toll of about 2,000.[6] The Jewish persecutions were trivial when compared with the brutal and widespread persecution by the Romans.[6]

Of the eleven remaining apostles (Judas Iscariot having killed himself), only one—John the Apostle, the son of Zebedee and the younger brother of the Apostle James—died of natural causes in exile. The other ten were reportedly martyred by various means including beheading, by sword and spear and, in the case of Peter, crucifixion upside down following the execution of his wife. The Romans were involved in some of these persecutions.

The New Testament, especially the Gospel of John, has traditionally been interpreted as relating Christian accounts of the Pharisee rejection of Jesus and accusations of the Pharisee responsibility for his crucifixion. The Acts of the Apostles depicts instances of early Christian persecution by the Sanhedrin, the Hebrew religious establishment of the time.[7]

Walter Laqueur argues that hostility between Christians and Jews grew over the generations. By the 4th century, John Chrysostom was arguing that the Pharisees alone, not the Romans, were responsible for the murder of Christ. However, according to Laqueur: "Absolving Pilate from guilt may have been connected with the missionary activities of early Christianity in Rome and the desire not to antagonize those they want to convert."[8]

At least by the 4th century, the consensus amongst scholars is that persecution by Jews of Christians has been traditionally overstated; according to James Everett Seaver,[9]

Much of Christian hatred toward the Jews was based on the popular misconception... that the Jews had been the active persecutors of Christians for many centuries... The... examination of the sources for fourth century Jewish history will show that the universal, tenacious, and malicious Jewish hatred of Christianity referred to by the church fathers and countless others has no existence in historical fact. The generalizations of patristic writers in support of the accusation have been wrongly interpreted from the fourth century to the present day. That individual Jews hated and reviled the Christians there can be no doubt, but there is no evidence that the Jews as a class hated and persecuted the Christians as a class during the early years of the fourth century.Persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire

Main article: Persecution of Christians in the Roman EmpireThe

Persecution under Nero, 64–68 AD

Main article: Great Fire of RomeThe first documented case of imperially supervised persecution of the Christians in the Roman Empire begins with Nero (37–68). In 64 AD, a great fire broke out in Rome, destroying portions of the city and economically devastating the Roman population. Nero himself was suspected as the arsonist by Suetonius,[10] claiming he played the lyre and sang the 'Sack of Ilium' during the fires. In his Annals, Tacitus (who claimed Nero was in Antium at the time of the fire's outbreak), stated that "to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians [or Chrestians[11]] by the populace" (Tacit. Annals XV, see Tacitus on Jesus). Suetonius, later to the period, does not mention any persecution after the fire, but in a previous paragraph unrelated to the fire, mentions punishments inflicted on Christians, defined as men following a new and malefic superstition. Suetonius however does not specify the reasons for the punishment, he just listed the fact together with other abuses put down by Nero.[12]

Persecution from the 2nd century to Constantine

By the mid-2nd century, mobs could be found willing to throw stones at Christians, and they might be mobilized by rival sects. The Persecution in Lyon was preceded by mob violence, including assaults, robberies and stonings (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5.1.7).

Further state persecutions were desultory until the 3rd century, though Tertullian's Apologeticus of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and addressed to Roman governors.[13] The "edict of Septimius Severus" familiar in Christian history is doubted by some secular historians to have existed outside Christian martyrology.

The first documentable Empire-wide persecution took place under Maximinus Thrax, though only the clergy were sought out. It was not until Decius during the mid-century that a persecution of Christian laity across the Empire took place. Christian sources aver that a decree was issued requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the Emperor and the established order. Decius authorized roving commissions visiting the cities and villages to supervise the execution of the sacrifices and to deliver written certificates to all citizens who performed them. Christians were often given opportunities to avoid further punishment by publicly offering sacrifices or burning incense to Roman gods, and were accused by the Romans of impiety when they refused. Refusal was punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture, and executions. Christians fled to safe havens in the countryside and some purchased their certificates, called libelli. Several councils held at Carthage debated the extent to which the community should accept these lapsed Christians.

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom. Roman authorities tried hard to avoid Christians because they "goaded, chided, belittled and insulted the crowds until they demanded their death."[14] According to Droge and Tabor, "in 185 the proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, was approached by a group of Christians demanding to be executed. The proconsul obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or cliffs they could jump off."[15] Such seeking after death is found in Tertullian's Scorpiace or in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch but was certainly not the only view of martyrdom in the Christian church. Both Polycarp and Cyprian, bishops in Smyrna and Carthage respectively, attempted to avoid martyrdom.

The Great Persecution

Main article: Diocletian Persecution The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1883).

The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1883).

The persecutions culminated with Diocletian and Galerius at the end of the third and beginning of the 4th century. The Great Persecution is considered the largest. Beginning with a series of four edicts banning Christian practices and ordering the imprisonment of Christian clergy, the persecution intensified until all Christians in the empire were commanded to sacrifice to the gods or face immediate execution. Over 20,000 Christians are thought to have died during Diocletian's reign. However, as Diocletian zealously persecuted Christians in the Eastern part of the empire, his co-emperors in the West did not follow the edicts and so Christians in Gaul, Spain, and Britannia were virtually unmolested.

This persecution lasted, until Constantine I came to power in 313 and legalized Christianity. It was not until Theodosius I in the later 4th century that Christianity would become the official religion of the Empire. Between these two events Julian II temporarily restored the traditional Roman religion and established broad religious tolerance renewing Pagan and Christian hostilities.

The conditions under which martyrdom was an acceptable fate or under which it was suicidally embraced occupied writers of the early Christian Church. Broadly speaking, martyrs were considered uniquely exemplary of the Christian faith, and few early saints were not also martyrs.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states that "Ancient, medieval and early modern hagiographers were inclined to exaggerate the number of martyrs. Since the title of martyr is the highest title to which a Christian can aspire, this tendency is natural". Estimates of Christians killed for religious reasons before the year 313 vary greatly, depending on the scholar quoted, from a high of almost 100,000 to a low of 10,000.

Persecutions of early Christians outside the Roman Empire

A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids, a scene of persecution by druids in ancient Britain painted by William Holman Hunt.

A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids, a scene of persecution by druids in ancient Britain painted by William Holman Hunt.

In 341, the Zoroastrian Shapur II ordered the massacre of all Christians in Persia. During the persecution, about 1,150 Christians were martyred under Shapur II.[16] In the 4th century, the Terving King Athanaric began persecuting Christians, many of whom were killed.[17]

Persecution of Christians during the Middle Ages

Persecution of Christians by Persians and Jews during Roman-Persian Wars

According to Antiochus Strategos, a 7th century monk in Palestine, shortly after the Persian army entered Jerusalem in 614, unprecedented looting and sacrilege took place. Church after church was burned down alongside the innumerable Christian artifacts, which were stolen or damaged by the ensuing arson. Given that Khosrau II generally practiced religious tolerance and did deem Christians respectfully, it is not known why Shahrbaraz ordered such a massacre. One reason could simply have been Shahrbaraz's rage at the resistance that had been offered by Jerusalem's Christian populace. Accounts from early Christian chroniclers suggest that 26,000 Jewish rebels entered the streets of the city. Some Jerusalem Christians were taken captive, gathered together and murdered in mass by Jews. The Greek historian Antiochus Strategos writes that captive Christians were gathered near Mamilla reservoir and the Jews offered to help them escape death if they "become Jews and deny Christ". The Christian captives refused, and the Jews in anger had purchased the Christians from Persians and massacred them on spot. Antiochus writes: Then the Jews... as of old they bought the Lord from the Jews with silver, so they purchased Christians out of the reservoir; for they gave the Persians silver, and they bought a Christian and slew him like a sheep. According to Antiochus, the total Christian death toll was 66,509, of which 24,518 corpses were found at Mamilla, many more than were found anywhere else in the city. Other sources give a figure of 60,000 slain. The Jews destroyed the Christian churches and the monasteries, books were burnt and monks and priests killed. According to Israeli archeologists, there was no destruction of churches. A mass burial grave at Mamilla cave was discovered in 1989 by Israeli archeologist Ronny Reich.

Persecution of Christians in the early and medieval Caliphates

In general, Christians subject to Islamic rule were allowed to practice their religion with some notable limitations, see Pact of Umar. As People of the Book they were awarded dhimmi status, which, although inferior to the status of Muslims, was more favourable than the plight of adherents of non-Abrahamic faiths.

At times, anti-Christian pogroms occurred. Under sharia, non-Muslims are obligated to pay jizya taxes, which contributed a significant proportion of income for the Islamic state and persuaded many Christians to convert to Islam (Stillman (1979), p. 160.). According to the Hanafi school of sharia, the testimony of a non-Muslim (such as a Christian) was not considered valid against the testimony of a Muslim. Other schools differed. Christian men were not allowed to marry a Muslim woman under sharia. Muslim men on the other hand were allowed to marry Christian women. Christians under Islamic rule had the right to convert to Islam or any other religion, while a murtad, or apostate of Islam, faced severe penalties or even hadd, which could include the death penalty.

Medieval Christian persecution of heresy

In the medieval period the Roman Catholic Church moved to suppress the Cathar heresy, the Pope having sanctioned a crusade against the Albigensians, during the course of which the massacre of Béziers took place, with between seven and twenty thousand deaths. Papal legate Arnaud Amalric, when asked how Catholics could be distinguished from Cathars once the city fell, famously replied, "Kill them all, God will know His own." Over the twenty-year period of this campaign an estimated 200,000 to 1,000,000 people were killed.[18][19]

John Huss, a Bohemian preacher of reformation, was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. Pope Martin V issued a bull on 17 March 1420 which proclaimed a crusade "for the destruction of the Wycliffites, Hussites and all other heretics in Bohemia".

The Crusades in the Middle East also spilled over into conquest of Eastern Orthodox Christians by Roman Catholics and attempted suppression of the Orthodox Church. The Waldenses were as well persecuted by the Catholic Church, but survive up to this day.

Early Modern period (1500 to 1815)

Reformation

The Reformation led to a long period of warfare and communal violence between Catholic and Protestant factions, leading to massacres and forced suppression of the alternative views by the dominant faction in much of Europe.

Anti-Catholic

Main article: Anti-CatholicismAnti-Catholicism officially began in 1534 during the English Reformation; the Act of Supremacy made the King of England the 'only supreme head on earth of the Church in England.' Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treason. It was under this act that Thomas More was executed. Queen Elizabeth I's scorn for Jesuit missionaries led to many executions at Tyburn. As punishment for the rebellion of 1641, almost all lands owned by Irish Catholics were confiscated and given to Protestant settlers. Under the penal laws no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691.[20] Catholic / Protestant strife has been blamed for much of "The Troubles", the ongoing struggle in Northern Ireland.

This attitude was carried to the English colonies in America, which eventually became the United States. In these colonies, Catholicism was introduced with the settling of Maryland in 1634; this colony offered a rare example of religious toleration in a fairly intolerant age, particularly amongst other English colonies which frequently exhibited a quite militant Protestantism. (See the Maryland Toleration Act, and note the pre-eminence of the Archdiocese of Baltimore in Catholic circles.) However, at the time of the American Revolution, Catholics formed less than 1% of the population of the thirteen colonies.

Anti-Eastern Orthodox

In 1656, Macarios III Zaim, who was the Greek Patriarch of Antioch, lamented over the atrocities committed by the Polish Catholics against followers of Greek Orthodoxy. Macarios was quoted as stating that seventy or eighty thousand followers of Eastern Orthodoxy were killed under hands of the Catholics. Greek Patriarch Macarios desired Turkish sovereignty over Catholic subjugation, stating:

God perpetuate the empire of the Turks for ever and ever! For they take their impost, and enter no account of religion, be their subjects Christians or Nazarenes, Jews or Samaritians; whereas these accursed Poles were not content with taxes and tithes from the brethren of Christ...[21]

Anti-Protestant

Main article: Anti-ProtestantismAnti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants were denounced as heretics and subject to persecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands, in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by Popes and Princes as the Counter Reformation. This resulted in religious wars and eruptions of sectarian hatred such as the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572.

Persecution of the Anabaptists

Main article: AnabaptistWhen the disputes between Lutherans and Roman Catholics gained a political dimension, both groups saw other groups of religious dissidents that were arising as a danger to their own security. The early "Täufer" (lit. "Baptists") were mistrusted and rejected by both religio-political parties. Religious persecution is often perpetrated as a means of political control, and this becomes evident with the Treaty of Augsburg in 1555. This treaty provided the legal groundwork for persecution of the Anabaptists.

China

Beginning in the late 17th century, Christianity was banned for at least a century in China by Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty after the Pope forbade Chinese Catholics from venerating their relatives or Confucius.[22] During the Boxer Rebellion, anti Christian Boxers, and Muslim Kansu Braves serving in the Chinese army attacked Christians.[23][24][25]

During the Northern Expedition, the Kuomintang incited anti-foreign, anti-Western sentiment. Portraits of Sun Yatsen replaced the crucifix in several churches, KMT posters proclaimed- "Jesus Christ is dead. Why not worship something alive such as Nationalism?". Foreign missionaries were attacked and anti foreign riots broke out.[26]

During the Northern Expedition, in 1926 in Guangxi, Muslim General Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing idols, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[27] It was reported that almost all of Buddhist monasteries in Guangxi were destroyed by Bai in this manner. The monks were removed.[28] Bai led a wave of anti foreignism in Guangxi, attacking American, European, and other foreigners and missionaries, and generally making the province unsafe for foreigners. Westerners fled from the province, and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.[29]

Japan

Tokugawa Ieyasu assumed control over Japan in 1600. Like Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he disliked Christian activities in Japan. The Tokugawa shogunate finally decided to ban Catholicism, in 1614 and in the mid-17th century it demanded the expulsion of all European missionaries and the execution of all converts. This marked the end of open Christianity in Japan.[30] The Shimabara Rebellion, led by a young Japanese Christian boy named Amakusa Shiro Tokisada, took place in 1637. After the Hara Castle fell, the shogunate's forces beheaded an estimated 37,000 rebels and sympathizers. Amakusa Shirō's severed head was taken to Nagasaki for public display, and the entire complex at Hara Castle was burned to the ground and buried together with the bodies of all the dead.[31]

Many of the Christians in Japan continued for two centuries to maintain their religion as Kakure Kirishitan, or hidden Christians, without any priests or pastors. Some of those who were killed for their Faith are venerated as the Martyrs of Japan by the Catholic Church, Anglican Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church.

Although Christianity was later allowed during the Meiji era, Christians were again persecuted during the period of State Shinto.

India

The Jamalabad fort route. Mangalorean Catholics had traveled through this route on their way to Seringapatam

The Jamalabad fort route. Mangalorean Catholics had traveled through this route on their way to Seringapatam

In spite of the fact that there have been relatively fewer conflicts between Muslims and Christians in India in comparison to those between Muslims and Hindus, or Muslims and Sikhs, the relationship between Muslims and Christians have been occasionally turbulent. With the advent of European colonialism in India throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Christians were systematically persecuted in a few Muslim ruled kingdoms in India.

Perhaps the most infamous acts of anti-Christian persecution by Muslims was committed by Tippu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore against the Mangalorean Catholic community from Mangalore and the erstwhile South Canara district on the southwestern coast of India. Tippu was widely reputed to be anti-Christian. The captivity of Mangalorean Catholics at Seringapatam, began on 24 February 1784 and ended on 4 May 1799.[32]

The Bakur Manuscript reports him as having said: "All Musalmans should unite together, and considering the annihilation of infidels as a sacred duty, labor to the utmost of their power, to accomplish that subject."[33] Soon after the Treaty of Mangalore in 1784, Tippu gained control of Canara.[34] He issued orders to seize the Christians in Canara, confiscate their estates,[35] and deport them to Seringapatam, the capital of his empire, through the Jamalabad fort route.[36] There were no priests among the captives. Together with Fr Miranda, all the 21 arrested priests were issued orders of expulsion to Goa, fined Rs 2 lakhs, and threatened death by hanging if they ever returned.[33]

Tippu ordered the destruction of 27 Catholic churches. Among them were the Church of Nossa Senhora de Rosario Milagres at Mangalore, Fr Miranda's Seminary at Monte Mariano, Church of Jesu Marie Jose at Omzoor, Chapel at Bolar, Church of Merces at Ullal, Imaculata Conceiciao at Mulki, San Jose at Perar, Nossa Senhora dos Remedios at Kirem, Sao Lawrence at Karkal, Rosario at Barkur, Immaculata Conceciao at Baidnur.[33] All were razed to the ground, with the exception of Igreja da Santa Cruz Hospet also known as Hospet Church at Hospet,owing to the friendly offices of the Chauta Raja of Moodbidri.[37]

According to Thomas Munro, a Scottish soldier and the first collector of Canara, around 60,000 of them,[38] nearly 92 percent of the entire Mangalorean Catholic community, were captured, only 7,000 escaped. Francis Buchanan gives the numbers as 70,000 captured, from a population of 80,000, with 10,000 escaping. They were forced to climb nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m) through the jungles of the Western Ghat mountain ranges. It was 210 miles (340 km) from Mangalore to Seringapatam, and the journey took six weeks. According to British Government records, 20,000 of them died on the march to Seringapatam. According to James Scurry, a British officer, who was held captive along with Mangalorean Catholics, 30,000 of them were forcibly converted to Islam. The young women and girls were forcibly made wives of the Muslims living there.[39] The young men who offered resistance were disfigured by cutting their noses, upper lips, and ears.[40] According to Mr. Silva of Gangolim, a survivor of the captivity, if a person who had escaped from Seringapatam was found, the punishment under the orders of Tippu was the cutting off of the ears, nose, the feet and one hand.[41]

The Archbishop of Goa wrote in 1800, "It is notoriously known in all Asia and all other parts of the globe of the oppression and sufferings experienced by the Christians in the Dominion of the King of Kanara, during the usurpation of that country by Tipu Sultan from an implacable hatred he had against them who professed Christianity."[33]

Tippu Sultan's invasion of the Malabar Coast had an adverse impact on the Syrian Malabar Nasrani community of the Malabar coast. Many churches in Malabar and Cochin were damaged. The old Syrian Nasrani seminary at Angamaly which had been the center of Catholic religious education for several centuries was razed to the ground by Tippu's soldiers. Many centuries-old religious manuscripts were lost forever. The church was later relocated to Kottayam where it still exists to this date. The Mor Sabor church at Akaparambu and the Martha Mariam Church attached to the seminary were destroyed as well. Tippu's army set fire to the church at Palayoor and attacked the Ollur Church in 1790. Furthernmore, the Arthat church and the Ambazhakkad seminary was also destroyed. Over the course of this invasion, many Syrian Malabar Nasrani were killed or forcibly converted to Islam. Most of the coconut, arecanut, pepper and cashew plantations held by the Syrian Malabar farmers were also indiscriminately destroyed by the invading army. As a result, when Tippu's army invaded Guruvayur and adjacent areas, the Syrian Christian community fled Calicut and small towns like Arthat to new centres like Kunnamkulam, Chalakudi, Ennakadu, Cheppadu, Kannankode, Mavelikkara, etc. where there were already Christians. They were given refuge by Sakthan Tamburan, the ruler of Cochin and Karthika Thirunal, the ruler of Travancore, who gave them lands, plantations and encouraged their businesses. Colonel Macqulay, the British resident of Travancore also helped them.[42]

Tippu's persecution of Christians also extended to captured British soldiers. For instance, there were a significant amount of forced conversions of British captives between 1780 and 1784. Following their disastrous defeat at the battle of Pollilur, 7,000 British men along with an unknown number of women were held captive by Tippu in the fortress of Seringapatnam. Of these, over 300 were circumcised and given Muslim names and clothes and several British regimental drummer boys were made to wear ghagra cholis and entertain the court as nautch girls or dancing girls. After the 10 year long captivity ended, James Scurry, one of those prisoners, recounted that he had forgotten how to sit in a chair and use a knife and fork. His English was broken and stilted, having lost all his vernacular idiom. His skin had darkened to the swarthy complexion of negroes, and moreover, he had developed an aversion to wearing European clothes.[43]

During the surrender of the Mangalore fort which was delievered in an armistice by the British and their subsequent withdrawal, all the Mestizos and remaining non-British foreigners were killed, together with 5,600 Mangalorean Catholics. Those condemned by Tippu Sultan for treachery were hanged instantly, the gibbets being weighed down by the number of bodies they carried. The Netravati River was so putrid with the stench of dying bodies, that the local residents were forced to leave their riverside homes.[33]

French Revolution

Main articles: Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution and Revolt in the VendéeThe Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution is a conventional description of a campaign, conducted by various Robespierre-era governments of France beginning with the start of the French Revolution in 1789, in order to eliminate any symbol that might be associated with the past, especially the monarchy.

The program included the following policies:[44][45][46]

- the deportation of clergy and the condemnation of many of them to death,

- the closing, desecration and pilaging of churches, removal of the word "saint" from street names and other acts to banish Christian culture from the public sphere

- removal of statues, plates and other iconography from places of worship

- destruction of crosses, bells and other external signs of worship

- the institution of revolutionary and civic cults, including the Cult of Reason and subsequently the Cult of the Supreme Being,

- the large scale destruction of religious monuments,

- the outlawing of public and private worship and religious education,

- forced marriages of the clergy,

- forced abjurement of priesthood, and

- the enactment of a law on 21 October 1793 making all nonjuring priests and all persons who harbored them liable to death on sight.

The climax was reached with the celebration of the Goddess "Reason" in Notre Dame Cathedral on 10 November.

Under threat of death, imprisonment, military conscription or loss of income, about 20,000 constitutional priests were forced to abdicate or hand over their letters of ordination and 6,000 – 9,000 were coerced to marry, many ceasing their ministerial duties.[47] Some of those who abdicated covertly ministered to the people.[47] By the end of the decade, approximately 30,000 priests were forced to leave France, and thousands who did not leave were executed.[48] Most of France was left without the services of a priest, deprived of/liberated from the sacraments and any nonjuring priest faced the guillotine or deportation to French Guiana.[49]

The March 1793 conscription requiring Vendeans to fill their district's quota of 300,000 enraged the populace, who took up arms as "The Catholic Army", "Royal" being added later, and fought for "above all the reopening of their parish churches with their former priests."[50] A massacre of 6,000 Vendée prisoners, many of them women, took place after the battle of Savenay, along with the drowning of 3,000 Vendée women at Pont-au-Baux and 5,000 Vendée priests, old men, women, and children killed by drowning at the Loire River at Nantes in what was called the "national bath" – tied in groups in barges and then sunk into the Loire.[51][52][53]

With these massacres came formal orders for forced evacuation; also, a 'scorched earth' policy was initiated: farms were destroyed, crops and forests burned and villages razed. There were many reported atrocities and a campaign of mass killing universally targeted at residents of the Vendée regardless of combatant status, political affiliation, age or gender.[54] By July 1796, the estimated Vendean dead numbered between 117,000 and 500,000, out of a population of around 800,000.[55][56][57] Some historians call these mass killings the first modern genocide, specifically because intent to exterminate the Catholic Vendeans was clearly stated,[58] though others have rejected these claims.

Modern era (1815 to 1989)

Ottoman Empire

Main articles: Armenian genocide, Assyrian genocide, and Greek genocideThe Young Turks government of the collapsing Ottoman Empire in 1915 persecuted Christian populations in Anatolia resulting in an estimated 2.1 million deaths, divided between roughly 1.2 Million Armenian Christians, 0.6 million Syriac/Assyrian Christians and 0.3 million Greek Orthodox Christians, a number of Georgians were also killed.

Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact Countries

Further information: Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union and Persecution of Christians in Warsaw Pact countriesAfter the Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks undertook a massive program to remove the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church from the government and Russian society, and to make the state atheist. Tens of thousands of churches were destroyed or converted to other uses, and many members of clergy were imprisoned for anti-government activities. An extensive education and propaganda campaign was undertaken to convince people, especially the children and youth, to abandon religious beliefs. This persecution resulted in the martyrdom of millions of Orthodox followers in the 20th century by the Soviet Union, whether intentional or not.

This persecution spread not only to the Orthodox, but also other groups, such as the Mennonites, who largely fled to the Americas.[59]

Before and after the October Revolution of 7 November 1917 (25 October Old Calendar) there was a movement within the Soviet Union to unite all of the people of the world under Communist rule (see Communist International). This included the Eastern European bloc countries as well as the Balkan States. Since some of these Slavic states tied their ethnic heritage to their ethnic churches, both the peoples and their church were targeted by the Soviet and its form of State atheism.[60][61] The Soviets' official religious stance was one of "religious freedom or tolerance", though the state established atheism as the only scientific truth (see also the Soviet or committee of the All-Union Society for the Dissemination of Scientific and Political Knowledge or Znanie which was until 1947 called The League of the Militant Godless and various Intelligentsia groups).[62][63][64] Criticism of atheism was strictly forbidden and sometimes resulted in imprisonment.[65] Some of the more high profile individuals executed include Metropolitan Benjamin of Petrograd, Priest and scientist Pavel Florensky and Bishop Gorazd Pavlik.

The Soviet Union was the first state to have as an ideological objective the elimination of religion. Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in the schools. Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed. It is estimated that 500,000 Russian Orthodox Christians were martyred in the gulags by the Soviet government, not including torture or other Christian denominations killed.[66][unreliable source?]

Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers along with execution included torture being sent to prison camps, labour camps or mental hospitals.[47][67] The result of state sponsored atheism was to transform the Church into a persecuted and martyred Church. In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution, 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[68]

Christ the Savior Cathedral Moscow after reconstruction

Christ the Savior Cathedral Moscow after reconstruction

The main target of the anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and 1930s was the Russian Orthodox Church, which had the largest number of faithful. A very large segment of its clergy, and many of its believers, were shot or sent to labor camps. Theological schools were closed, and church publications were prohibited. In the period between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in the Russian Republic fell from 29,584 to less than 500. Between 1917 and 1940, 130,000 Orthodox priests were arrested. The widespread persecution and internecine disputes within the church hierarchy lead to the seat of Patriarch of Moscow being vacant from 1925–1943.

After Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, Joseph Stalin revived the Russian Orthodox Church to intensify patriotic support for the war effort. By 1957 about 22,000 Russian Orthodox churches had become active. But in 1959 Nikita Khrushchev initiated his own campaign against the Russian Orthodox Church and forced the closure of about 12,000 churches. By 1985 fewer than 7,000 churches remained active.[68]

In the Soviet Union, in addition to the methodical closing and destruction of churches, the charitable and social work formerly done by ecclesiastical authorities was taken over by the state. As with all private property, Church owned property was confiscated into public use. The few places of worship left to the Church were legally viewed as state property which the government permitted the church to use. After the advent of state funded universal education, the Church was not permitted to carry on educational, instructional activity for children. For adults, only training for church-related occupations was allowed. Outside of sermons during the celebration of the divine liturgy it could not instruct or evangelise to the faithful or its youth. Catechism classes, religious schools, study groups, Sunday schools and religious publications were all illegal and or banned. This caused many religious tracts to be circulated as illegal literature or samizdat.[47] This persecution continued, even after the death of Stalin until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Orthodox Church has recognized a number of New Martyrs as saints, some executed during Mass operations of the NKVD under directives like NKVD Order No. 00447.

19th and 20th century Mexico

Main article: Persecution of Christians in MexicoIn the 19th century, Benito Juárez confiscated a large amount of church land. The Mexican government's campaign against the Catholic Church after the Mexican Revolution culminated in the 1917 constitution which contained numerous articles which Catholics considered violative of their civil rights: outlawing monastic religious orders, forbidding public worship outside of church buildings, restricted religious organizations' rights to own property, and taking away basic civil rights of members of the clergy (priests and religious leaders were prevented from wearing their habits, were denied the right to vote, and were not permitted to comment on public affairs in the press and were denied the right to trial for violation of anticlerical laws). When the first embassy of the Soviet Union in any country was opened in Mexico, the Soviet ambassador remarked that "no other two countries show more similarities than the Soviet Union and Mexico".[69]

When the Church publicly condemned the anticlerical measures which had not been strongly enforced, the atheist President Plutarco Calles sought to vigorously enforce the provisions and enacted additional anti-Catholic legislation known as the Calles Law. At this time, some in the United States government, considering Calles' regime Bolshevik, started to refer to Mexico as "Soviet Mexico".[70]

Weary of the persecution, in many parts of the country a popular rebellion called the Cristero War began (so named because the rebels felt they were fighting for Christ himself). The effects of the persecution on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed.[71] Where there were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[71][72] By 1935, 17 states had no priest at all.[73] In the second Cristero rebellion (1932), the Cristeros took particular exception to the socialist education, which Calles had also implemented but which President Cardenas had added to the 1917 Mexican Constitution.[74][75]

Anti-Mormonism

Main articles: Anti-Mormonism and Violence against MormonsThe Latter Day Saint Movement, (Mormons) have been persecuted since their founding in the 1830s. This persecution drove them from New York and Ohio to Missouri, where they continued to suffer violent attacks. In 1838, Gov. Lilburn Boggs declared that Mormons had made war on the state of Missouri, and "must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state"[76]

The Mormons subsequently fled to Nauvoo, Illinois, where hostilities again escalated. In Carthage, Ill., where Joseph Smith was being held on the charge of treason, a mob stormed the jail and killed him. Smith's brother, Hyrum, was also killed. After a succession crisis, most united under Brigham Young, who organized an evacuation from the United States after the federal government refused to protect them.[77] 70,000 Mormon pioneers crossed the Great Plains to settle in the Salt Lake Valley and surrounding areas. After the Mexican-American War, the area became the US territory of Utah. Over the next 46 years several actions by the federal government were directed against Mormons in the Mormon Corridor, including the Utah War, Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, Poland Act, Reynolds v. United States, Edmunds Act, and Edmunds-Tucker Act.

Madagascar

Queen Ranavalona I (reigned 1828–1861) issued a royal edict prohibiting the practice of Christianity in Madagascar, expelled British missionaries from the island, and sought to stem the growth of conversion to Christianity within her realm. Approximately 60–80 Malagasy citizens were put to death during this period as a consequence of their refusal to recant their Christian faith. Far more, however, were punished in other ways: many were required to undergo the tangena ordeal, while others were condemned to hard labor or the confiscation of their land and property, and many of these consequently died. The tangena ordeal was commonly administered to determine the guilt or innocence of an accused person for any crime, including the practice of Christianity, and involved ingestion of the poison contained within the nut of the tangena tree (Cerbera odollam). Survivors were deemed innocent, while those who perished were assumed guilty. Malagasy Christians would remember this period as ny tany maizina, or "the time when the land was dark". Persecution of Christians intensified in 1840, 1849 and 1857; in 1849, deemed the worst of these years by British missionary to Madagascar W.E. Cummins (1878), 1,900 people were fined, jailed or otherwise punished in relation to their Christian faith, including 18 executions.[78]

Spain - Anti-Catholicism

"Execution" of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by a republican firing squad.[79] The image was originally published in the London Daily Mail with a caption noting the "Spanish Reds' war on religion."[80]

"Execution" of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by a republican firing squad.[79] The image was originally published in the London Daily Mail with a caption noting the "Spanish Reds' war on religion."[80] Main article: Red Terror (Spain)

Main article: Red Terror (Spain)Persecution of Catholics mostly, before and at the beginning, of the Spanish Civil war (1936-1939), involved the murder of almost 7,000 priests and other clergy, as well as thousands of lay people, by sections of nearly all the leftist groups because of their faith.[81][82] The Republican government which had come to power in Spain in 1931 was strongly anti-Catholic, prohibiting religious education – even in private school, prohibiting any education by religious orders, seizing Church property and expelling the Jesuits from the country. On 3 June 1933 Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis, in which he described the expropriation of all Church buildings, episcopal residences, parish houses, seminaries and monasteries. By law, they became property of the Spanish State, to which the Church had to pay rent and taxes in order to continuously use these properties. "Thus the Catholic Church is compelled to pay taxes on what was violently taken from her"[83] Religious vestments, liturgical instruments, statues, pictures, vases, gems and similar objects necessary for worship were expropriated as well or desecrated.[84] Numerous churches and temples were destroyed by burning, after they were nationalized. All private Catholic schools from religious orders and Congregations were expropriated. The purpose was to create solely secular schools there instead.[85] Pope Pius XI, who faced similar persecutions in the USSR and Mexico, called on Spanish Catholics to defend themselves against the persecution with all legal means.

During the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, and especially in the early months of the conflict, individual clergymen and entire religious communities were executed by leftists, which included communists and anarchists. The death toll of the clergy alone included 13 bishops, 4,172 diocesan priests and seminarians, 2,364 monks and friars and 283 nuns, for a total of 6,832 clerical victims.[81]

In addition to murders of clergy and the faithful, destruction of churches and desecration of sacred sites and objects were widespread. On the night of 19 July 1936 alone, some fifty churches were burned.[86] In Barcelona, out of the 58 churches, only the Cathedral was spared, and similar desecrations occurred almost everywhere in Republican Spain.[87]

Exceptions were Biscay and Guipuscoa where the Christian Democratic Basque Nationalist Party, after some hesitation, supported the Republic while halting persecution in the areas held by the Basque Government. All Catholic churches in the Republican zone were closed[citation needed]. The desecration was not limited to Catholic churches, as synagogues and Protestant churches were also pillaged and closed. Some small Protestant churches were spared.[88]

The terror has been called the "most extensive and violent persecution of Catholicism in Western History, in some way even more intense than that of the French Revolution." [89] The persecution drove Catholics to the Nationalists, even more than would have been expected, as these defended their religious interests and survival.[89]

Spain - Anti-Protestantism

In Franco's authoritarian Spanish State (1936-1975), Protestantism was deliberately marginalized and persecuted. During the Civil War, Franco's regime persecuted the country's 30,000[90] Protestants, and forced many Protestant pastors to leave the country. Once authoritarian rule was established, non-Catholic Bibles were confiscated by police and Protestant schools were closed.[91] Although the 1945 Spanish Bill of Rights granted freedom of private worship, Protestants suffered legal discrimination and non-Catholic religious services were not permitted publicly, to the extent that they could not be in buildings which had exterior signs indicating it was a house of worship and that public activities were prohibited.[90][92]

While the Catholic Church was declared official and enjoyed a close relation to the state, parts of the Basque clergy harbored nationalist ideas opposed to Spanish centralism and were persecuted and imprisoned in a "Concordate jail" reserved for criminal clergy.

Nazi Germany

Hitler and the Nazis enjoyed widespread support from traditional Christian communities, mainly due to a common cause against the anti-religious German Bolsheviks. Once in power, the Nazis moved to consolidate their power over the German churches and bring them in line with Nazi ideals.

The Third Reich founded their own version of Christianity called Positive Christianity which made major changes in its interpretation of the Bible which said that Jesus Christ was the son of God, but was not a Jew and claimed that Christ despised Jews, and that the Jews were the ones solely responsible for Christ's death. Thus, the Nazi government consolidated religious power, using allies to consolidate Protestant churches into the Protestant Reich Church, which was effectively an arm of the Nazi Party.[citation needed]

Dissenting Christians went underground and formed the Confessing Church, which was persecuted as a subversive group by the Nazi government. Many of its leaders were arrested and sent to concentration camps, and left the underground mostly leaderless. Church members continued to engage in various forms of resistance, including hiding Jews during the Holocaust and various attempts, largely unsuccessful, to prod the Christian community to speak out on the part of the Jews.[citation needed]

The Catholic Church was particularly suppressed in Poland because of the Church's opposition to many of Nazi Party's beliefs. Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 3,000 members, 18% of the Polish clergy,[93] were murdered; of these, 1,992 died in concentration camps. In the annexed territory of Reichsgau Wartheland it was even harsher than elsewhere. Churches were systematically closed, and most priests were either killed, imprisoned, or deported to the General Government. The Germans also closed seminaries and convents persecuting monks and nuns throughout Poland. In Pomerania, all but 20 of the 650 priests were shot or sent to concentration camps. Eighty percent of the Catholic clergy and five of the bishops of Warthegau were sent to concentration camps in 1939; in the city of Breslau (Wrocław), 49% of its Catholic priests were killed; in Chełmno, 48%. One hundred eight of them are regarded as blessed martyrs.[93] Among them, Maximilian Kolbe was canonized as a saint.

Protestants in Poland did not fare well either. In the Cieszyn region of Silesia every single Protestant clergy was arrested and deported to the death camps.[93]

Not only were Polish Christians persecuted by the Nazis, in the Dachau concentration camp alone, 2,600 Catholic priests from 24 different countries were killed.[93]

Outside mainstream Christianity, Jehovah's Witnesses were direct targets of the Holocaust, for their refusal to swear allegiance to the Nazi government. Many Jehovah's Witnesses were given the chance to deny their faith and swear allegiance to the state, but few agreed. Over 12,000 Witnesses were sent to the concentration camps, and estimated 2,500–5,000 died in the Holocaust.

Jehovah's Witnesses

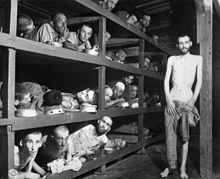

Main article: Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses The Buchenwald concentration camp is one of the camps in which Jehovah's Witnesses prisoners were labored.

The Buchenwald concentration camp is one of the camps in which Jehovah's Witnesses prisoners were labored.

Since Charles Taze Russell's Bible Students group had formed after the American Civil War there was no formal position on military service till 1914, when the body came out against military service. Jehovah's Witnesses are forbidden by their religion to engage in violence, or to join the military.

In Nazi Germany in the 1930s and early 1940s, Jehovah's Witnesses who refused to renounce pacifism and were placed in concentration camps as a result. The Nazi government gave detained Jehovah's Witnesses the option of release by signing a document indicating renouncement of their faith, submission to state authority, and support of the German military.[94]

Historian Hans Hesse said, "Some five thousand Jehovah's Witnesses were sent to concentration camps where they alone were 'voluntary prisoners', so termed because the moment they recanted their views, they could be freed. Some lost their lives in the camps, but few renounced their faith".[95][96]

Political and religious animosity against Jehovah's Witnesses has at times led to mob action and government oppression in various countries, including Cuba, the United States, Canada and Singapore. The religion's doctrine of political neutrality has led to imprisonment of members who refused conscription (for example in Britain during World War II and afterwards during the period of compulsory national service).

Current situation (1989 to present)

In the contemporary world, Christians, according to Pope Benedict XVI, are the most persecuted religious group.[97] According to the World Evangelical Alliance, over 200 million Christians in at least 60 countries are denied fundamental human rights solely because of their faith.[98] Persecutions occur in North Korea, many Muslim countries, India, China, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Muslim world

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, Abdul Rahman, a 41-year-old citizen, was charged in 2006 with rejecting Islam (apostasy), a crime punishable by death under Sharia law. He has since been released into exile in the West under intense pressure from Western governments.[99][100] In 2008, the Taliban killed a British charity worker, Gayle Williams, "because she was working for an organisation which was preaching Christianity in Afghanistan" even though she was extremely careful not to try to convert Afghans.[101]

Albania/Kosovo

See also: Persecution of Serbs and other non-Albanians in Kosovo and Pogrom in KosovoAlgeria

On the night of 26–27 March 1996, seven monks from the monastery of Tibhirine in Algeria, belonging to the Roman Catholic Trappist Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (O.C.S.O.), were kidnapped in the Algerian Civil War. They were held for two months, and were found dead on 21 May 1996. The circumstances of their kidnapping and death remain controversial; the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) claims responsibility for both, but the then French military attaché, retired General Francois Buchwalter, reports that they were accidentally killed by the Algerian army in a rescue attempt, and claims have been made that the GIA itself was a cat's paw of Algeria's secret services (DRS).

Islamists looted, and burned to the ground, a Pentecostal church in Tizi Ouzou on 9 January 2010. The pastor was quoted as saying that worshipers fled when local police left a gang of local rioters unchecked.[102]

Egypt

See also: Persecution of CoptsPart of a series of articles on

Modern persecution of

Coptic Christians

Massacres

Alexandria Bombing

Nag Hammadi Massacre

Kosheh MassacreIncidents

Imbaba church attacks

Alexandria riots

Attack on Saint Fana Monastery

Maspero demonstrationsNotable figures

Sidhom Bishay · Master Malati

Mohammed Hegazy

Bahaa el-Akkad

Mark GabrielWhile the Egyptian government does not have a policy to persecute Christians, it discriminates against them and hampers their freedom of worship. Its agencies sporadically persecute Muslim converts to Christianity.[103] The government enforces Hamayouni Decree restrictions on building or repairing churches. These same restrictions, however, do not apply to mosques.[103]

The government has effectively restricted Christians from senior government, diplomatic, military, and educational positions, and there has been increasing discrimination in the private sector.[103][104] The government subsidizes media which attack Christianity and restricts Christians access to the state-controlled media.[103]

In Egypt the government does not officially recognize conversions from Islam to Christianity; because certain interfaith marriages are not allowed either, this prevents marriages between converts to Christianity and those born in Christian communities, and also results in the children of Christian converts being classified as Muslims and given a Muslim education.[103] The government also applies religiously discriminatory laws and practices concerning clergy salaries.[103]

Foreign missionaries are allowed in the country only if they restrict their activities to social improvements and refrain from proselytizing. The Coptic Pope Shenouda III was internally exiled in 1981 by President Anwar Sadat, who then chose five Coptic bishops and asked them to choose a new pope. They refused, and in 1985 President Hosni Mubarak restored Pope Shenouda III, who had been accused of fomenting interconfessional strife. Particularly in Upper Egypt, the rise in extremist Islamist groups such as the Gama'at Islamiya during the 1980s was accompanied by attacks on Copts and on Coptic churches; these have since declined with the decline of those organizations, but still continue. The police have been accused of siding with the attackers in some of these cases.[105]

Many colleges dictate quotas for Coptic students, often around 1 or 2% despite the group making up 15% of the country's population. There is also a separate tax-funded education system called Al Azhar, catering to students from elementary to college level, which accepts no Christian Coptic students, teachers or administrators.

Hundreds of Christian Coptic girls have been kidnapped and forcibly converted to Islam, as well as being victims of rape and forced marriage to Muslim men.[104][citation needed]

On 2 January 2000, at least 21 Christians were killed by Muslims in Al Kosheh in southern Egypt. Christian properties were also burned.[106][citation needed]

In April 2006, one person was killed and twelve injured in simultaneous knife attacks on three Coptic churches in Alexandria.[107]

In November 2008, several thousand Muslims attacked a Coptic church in a suburb of Cairo on the day of its inauguration, forcing 800 Coptic Christians to barricade themselves in.[108]

In April 2009, two Christian men were shot dead and another was injured by Muslim men after an Easter vigil in the south of Egypt.[109]

On 18 September 2009, a Muslim man called Osama Araban beheaded a Coptic Christian man in the village of Bagour, and injured 2 others in 2 different villages. He was arrested the following day.[110]

On the eve of 7 January 2010, after the Eastern Christmas Mass finished (which finishes around midnight), Copts were going out of Mar-Yuhanna (St. John) church in Nag Hammadi city when three Muslim men in a car near the church opened fire killing 8 Christians and injuring another 10.[111][112]

On 2011 New Year's Eve, just 20 minutes after midnight as Christians were leaving a Coptic Orthodox Church in the city of Alexandria after a New Year's Eve service a car bomb exploded in front of the Church killing more than 20 and injuring more than 75.[113][114][115]

On 7 May 2011, an armed group of Islamists, including Salafists, attacked and set fire to two churches including Saint Menas Coptic Orthodox Christian Church and the Coptic Church of the Holy Virgin, in Cairo. The attacks resulted in the deaths of 12 people and more than 230 wounded. It is reported that the events were triggered by a mixed marriage between a Christian woman and a Muslim man.[116]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, religious conflicts have typically occurred in Western New Guinea, Maluku (particularly Ambon), and Sulawesi. The presence of Muslims in these regions is in part a result of the transmigrasi program of population re-distribution. Conflicts have often occurred because of the aims of radical Islamist organizations such as Jemaah Islamiah or Laskar Jihad to impose Sharia,[117][118] with such groups attacking Christians and destroying over 600 churches.[119] In 2006 three Christian girls were beheaded as retaliation for previous Muslim deaths in Christian-Muslim rioting.[120] The men were imprisoned for the murders, including Jemaah Islamiyah's district ringleader Hasanuddin.[121] On going to jail, Hasanuddin said, "It's not a problem (if I am being sentenced to prison), because this is a part of our struggle."[122]

In January 1999, anti-Christian violence erupted by local Muslims.[123][124] "Tens of thousands died when Moslem gunmen terrorized Christians who had voted for independence in East Timor."[125]

Iran

Though Iran recognizes Assyrian and Armenian Christians as a religious minority (along with Jews and Zoroastrians) and they have representatives in the Parliament, after the 1979 Revolution, Muslim converts to Christianity (typically to Protestant Christianity) have been arrested and sometimes executed.[126] Youcef Nadarkhani is an Iranian Christian pastor who has been sentenced to death for refusing to recant his faith.[127] See also: Christianity in Iran.

Iraq

According to UNHCR, although Christians represent less than 5% of the total Iraqi population, they make up 40% of the refugees now living in nearby countries.[128] Northern Iraq remained predominantly Christian until the destructions of Tamerlane at the end of the 14th century. The Church of the East has its origin in what is now South East Turkey. By the end of the 13th century there were twelve Nestorian dioceses in a strip from Peking to Samarkand. When the 14th-century Muslim warlord of Turco-Mongol descent, Timur (Tamerlane), conquered Persia, Mesopotamia and Syria, the civilian population was decimated. Timur had 70,000 Assyrian Christians beheaded in Tikrit, and 90,000 more in Baghdad.[129][130]

In the 16th century, Christians were half the population of Iraq.[131] In 1987, the last Iraqi census counted 1.4 million Christians.[132] They were tolerated under the secular regime of Saddam Hussein, who even made one of them, Tariq Aziz, his deputy. However persecution by Saddam Hussein continued against the Christians on a cultural and racial level, as the vast majority are Ethnic Assyrians (aka Chaldo-Assyrians). The Assyrian -Aramaic language and written script was repressed, the giving of Hebraic/Aramaic Christian names or Assyrio-Babylonian names forbidden(Tariq Aziz real name is Michael Youhanna for example), and Saddam exploited religious differences between Assyrian denominations. Assyrians were ethnically cleansed from their towns and villages under the Anfal Campaign in 1988.

Recently, Chaldo-Assyrian Christians have seen their total numbers slump to about 500-000 to 800,000 today, of whom 250,000 live in Baghdad.[133] An exodus to the neighboring countries of Syria, Jordan and Turkey has left behind closed parishes, seminaries and convents. As a small minority without a militia of their own, Assyrian Christians have been persecuted by both Shi’a and Sunni Muslim militias, and also by criminal gangs.[134][135]

Many Assyrian Christians are departing for their northern heartlands in the Nineveh plains around Mosul.[citation needed]

Assyrian armed militia are now being set up (in 2010) to protect Assyrian towns and villages.[citation needed]

As of 21 June 2007, the UNHCR estimated that 2.2 million Iraqis had been displaced to neighboring countries, and 2 million were displaced internally, with nearly 100,000 Iraqis fleeing to Syria and Jordan each month.[136][137] A 25 May 2007 article notes that in the past seven months only 69 people from Iraq have been granted refugee status in the United States.[138]

Chaldean Catholic priest Fr. Ragheed Aziz Ganni and subdeacons Basman Yousef Daud, Wahid Hanna Isho, and Gassan Isam Bidawed were killed in the ancient city of Mosul last year.[139] Fr. Ragheed Aziz Ganni was driving with his three deacons when they were stopped and demanded to convert to Islam, when they refused they were shot.[139] Six months later, the body of Paulos Faraj Rahho, archbishop of Mosul, was found buried near Mosul. He was kidnapped on 29 February 2008 when his bodyguards and driver were killed.[140]

In 2004, five churches were destroyed by bombing. Tens of thousands of Christians fled the country.[141][142]

In 2010-11-01 was an attack on the Our Lady of Salvation Syriac Catholic cathedral[143] of Baghdad, Iraq, that took place during Sunday evening Mass on 31 October 2010. The attack left at least 58 people dead, after more than 100 had been taken hostage. The al-Qaeda-linked Sunni insurgent group[144]

The Islamic State of Iraq claimed responsibility for the attack; though Shia cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and Iraq's highest Catholic cleric condemned the attack, amongst others.

Lebanon

The war in Lebanon saw a number of massacres of both Christians and Muslims. Among the earliest was the Damour Massacre in 1976 when Palestinian militias attacked Christian civilians. According to an eyewitness: The attack took place from the mountain behind "It was an apocalypse," [said Father Mansour Labaky, a Christian Maronite priest who survived the massacre at Damour:] 'They were coming, thousands and thousands, shouting "Allahu Akbar! (God is great!) Let us attack them for the Arabs, let us offer a holocaust to Mohammad!", And they were slaughtering everyone in their path, men, women and children.'[145][146][147] The persecution in Lebanon combined sectarian, political, ideological, and retaliation reasons. The Syrian regime was also involved in persecuting Christians as well as Muslims in Lebanon.

In 2002, a currently unidentified gunman killed Bonnie Penner Witherall at a prenatal clinic in Sidon, Lebanon. She had been proselytizing and attempting to convert Muslims to Christianity.[148]

Malaysia

See also: Freedom of religion in MalaysiaIn Malaysia, although Islam is the official religion, Christianity is mostly tolerated.[citation needed] However, in order to be a member of the majority race (the Malays), one is legally required to be a Muslim.[citation needed] If a non-Muslim marries a Muslim, they are legally required to convert to Islam.[citation needed] There has been a debate over whether Malaysia is a liberal Islamic state or a very religious secular state.[citation needed]

Christians are forbidden to proselytize Muslims. Only Muslims are allowed to proselytize. In the 21st century, Christians have been accused of proselytizing Muslims. This accusation led to a raid on a Christian church by the Religious Police.[149].

Pakistan

In Pakistan 1.5% of the population are Christian. Pakistani law mandates that "blasphemies" of the Qur'an are to be met with punishment. Ayub Masih, a Christian, was convicted of blasphemy and sentenced to death in 1998. He was accused by a neighbor of stating that he supported British writer Salman Rushdie, author of The Satanic Verses. Lower appeals courts upheld the conviction. However, before the Pakistan Supreme Court, his lawyer was able to prove that the accuser had used the conviction to force Masih's family off their land and then acquired control of the property. Masih has been released.[150]

In October 2001, gunmen on motorcycles opened fire on a Protestant congregation in the Punjab, killing 18 people. The identify of the gunmen are unknown. Officials think it might be a banned Islamic group.[151]

In March 2002, five people were killed in an attack on a church in Islamabad, including an American schoolgirl and her mother.[152]

In August 2002, masked gunmen stormed a Christian missionary school for foreigners in Islamabad, six people were killed and three injured. None of those killed were children of foreign missionaries.[153]

In August 2002, grenades were thrown at a church in the grounds of a Christian hospital in north-west Pakistan, near Islamabad, killing three nurses.[154]

On 25 September 2002 two terrorists entered the "Peace and Justice Institute", Karachi, where they separated Muslims from the Christians, and then murdered seven Christians by shooting them in the head.[155][156] All of the victims were Pakistani Christians. Karachi police chief Tariq Jamil said the victims had their hands tied and their mouths had been covered with tape.

In December 2002, three young girls were killed when hand grenade was thrown into a church near Lahore on Christmas Day.[157]

In November 2005 3,000 militant Islamists attacked Christians in Sangla Hill in Pakistan and destroyed Roman Catholic, Salvation Army and United Presbyterian churches. The attack was over allegations of violation of blasphemy laws by a Pakistani Christian named Yousaf Masih. The attacks were widely condemned by some political parties in Pakistan.[158]

On 5 June 2006 a Pakistani Christian stonemason, Nasir Ashraf, was working near Lahore when he drank water from a public facility using a glass chained to the facility. He was assaulted by Muslims for "Polluting the glass". A mob developed, who beat Ashraf, calling him a "Christian dog". Bystanders encouraged the beating and joined in. Ashraf was eventually hospitalized.[159]

One year later, in August 2007, a Christian missionary couple, Rev. Arif and Kathleen Khan, were gunned down by militant Islamists in Islamabad. Pakistani police believed that the murders was committed by a member of Khan's parish over alleged sexual harassment by Khan. This assertion is widely doubted by Khan's family as well as by Pakistani Christians.[160] [161]

In August 2009, six Christians, including 4 women and a child, were burnt alive by Muslim militants and a church set ablaze in Gojra, Pakistan when violence broke out after alleged desecration of a Qur'an in a wedding ceremony by Christians.[162][163]

On Nov. 8, 2010, a Christian woman from Punjab Province, Asia Noreen Bibi, was sentenced to death by hanging for violating Pakistan's blasphemy law. The accusation stemmed from a 2009 incident in which Bibi became involved in a religious argument after offering water to thirsty Muslim farm workers. The workers later claimed that she had blasphemed the Prophet Muhammed. As of 8 April 2011, Bibi is in solitary confinement. Her family has fled. No one in Pakistan convicted of blasphemy has ever been executed. A cleric has offered $5,800 to anyone who kills her.[164][165]

On 2 March 2011, the only Christian minister in the Pakistan government was shot dead. He was targeted for opposing the anti-free speech "blasphemy" law, which punishes insulting Islam or its Prophet.[166] A fundamentalist Muslim group claimed responsibility.[167]

Saudi Arabia

"Non-Muslim Bypass:" Non-Muslims are barred from entering Mecca. An example of religious segregation.[168][169]

"Non-Muslim Bypass:" Non-Muslims are barred from entering Mecca. An example of religious segregation.[168][169] See also: Freedom of religion in Saudi Arabia

See also: Freedom of religion in Saudi ArabiaSaudi Arabia is an Islamic state that practices Wahhabism and restricts all other religions, including the possession of religious items such as the Bible, crucifixes, and Stars of David.[170] Christians are arrested and lashed in public for practicing their faith openly.[171] Strict sharia is enforced. Muslims are forbidden to convert to another religion. If one does so and does not recant, they may be executed.[citation needed]

Somalia

In Somalia 25 November 2010 Nurta Mohamed Farah, age 17. was shot and killed after fleeing her parents home where she had endured much torture and drugging, by them, in hopes that she would renounce her faith in Jesus Christ.[172]

Sudan

In Sudan, it is estimated that over 1.5 million Christians have been killed by the Janjaweed, the Arab Muslim militia, and even suspected Islamists in northern Sudan since 1984.[173]

It should also be noted that Sudan's several civil wars (which often take the form of genocidal campaigns) are often not only or purely religious in nature, but also ethnic, as many black Muslims, as well as Muslim Arab tribesmen, have also been killed in the conflicts.

It is estimated that as many as 200,000 people had been taken into slavery during the Second Sudanese Civil War. The slaves are mostly Dinka people.[174][175]

Turkey

In modern Turkey, the Istanbul pogrom was a state-sponsored and state-orchestrated pogrom that compelled Greek Christians to leave Istanbul, the first Christian city in violation to the Treaty of Lausanne (see Istanbul Pogrom). The issue of Christian genocides by the Turks may become a problem, since Turkey wishes to join the European Union.[176]

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is still in a difficult position. Turkey requires by law that the Ecumenical Patriarch must be an ethnic Greek, holding Turkish citizenship by birth, although most of the Greek minority has been expelled. The state's expropriation of church property and the closing of the Orthodox Theological School of Halki are also difficulties faced by the Church of Constantinople. Despite appeals from the United States, the European Union and various governmental and non-governmental organizations, the School remains closed since 1971. In November 2007, a 17th Century chapel of Our Lord's Transfiguration at the Halki seminary was almost totally demolished by the Turkish forestry authority.[177] There was no advanced warning given for the demolition work and it was only stopped after appeals by the Ecumenical Patriarch.[178]

Persecution of Christians has continued in modern Turkey. On 5 February 2006, the Catholic priest Andrea Santoro was murdered in Trabzon by a student influenced by the reactions following the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy.[179] On 18 April 2007, 3 Christians were murdered in the bible publishing firm in Malatya,[180][181] coincidentally, the hometown of Mehmet Ali Ağca, the assassin who shot and wounded Pope John Paul II on 13 May 1981. In December 2007, Adriano Franchini, a catholic priest of the Capuchin order in Turkey, was stabbed in the stomach after Sunday mass. Franchini led the church of the Virgin Mary in Ephesus.[182]

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974. The United Nations has documented their systematic destruction of churches of the Church of Cyprus from 1974 though 2003.[183][184] Many churches were vandalized and their artifacts stolen.[185] Church mosaics and frescoes were removed and ended up in Europe’s black market or sold openly in specialist stores and auction-houses. Some churches were demolished and some have had their use changed to mosques and stables.[186]

Yemen

Three Christian missionaries were killed in their hospital in Jibla, Yemen in December 2002. A gunman, apprehended by the authorities, said that he did it "for his religion."[187]

Other countries with large Muslim populations

India

Muslims in India who convert to Christianity have been subjected to harassment, intimidation, and attacks by Muslims. In Jammu and Kashmir, the only Indian state with a Muslim majority, a Christian convert and missionary, Bashir Tantray, was killed, allegedly by militant Islamists in 2006.[188] A Christian priest, K.K. Alavi, a 1970 convert from Islam,[189] thereby raised the ire of his former Muslim community and received many death threats. An Islamic terrorist group named "The National Development Front" actively campaigned against him.[190] In the southern state of India, Kerala, Islamic Terrorists chopped off the hand of Professor T.J.Joseph due to allegation of blasphemy of prophet.

Nigeria

In the 11 Northern states of Nigeria that have introduced the Islamic system of law, the Sharia, sectarian clashes between Muslims and Christians have resulted in many deaths, and some churches have been burned. More than 30,000 Christians were displaced from their homes Kano, the largest city in northern Nigeria.[191]

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Abu Sayyaf has attacked and killed Christians.[192]

Hindu extremism in India