- Istanbul Pogrom

Infobox civilian attack

title = Istanbul Pogrom

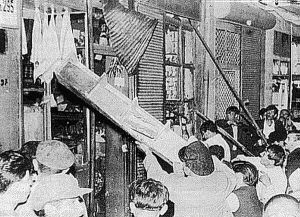

caption = Turkish mob attacking Greek property.

location =Istanbul ,Turkey

target = Property of the Greek population of the city.

date = 6–7 September 1955

type = Mob attack

fatalities = 10+ killed

susperps =Deep state , through the DP government.Birand, Mehmet Ali. “ [http://www.turkishdailynews.com.tr/article.php?enewsid=22723 The shame of Sept. 6–7 is always with us] ,” "Turkish Daily News ", 7 September 2005.]The Istanbul Pogrom (also known as Istanbul Riots; Lang-el|Σεπτεμβριανά (Events of September); Lang-tr|6–7 Eylül Olayları (Events of September 6–7)), was a

pogrom directed primarily atIstanbul 's 150,000-strongGilson, George. “ [http://www.athensnews.gr/athweb/nathens.print_unique?e=C&f=13136&m=A10&aa=1&eidos=S Destroying a minority: Turkey’s attack on the Greeks] ”, book review of (Vryonis 2005), "Athens News ", 24 June 2005.] Greekminority on 6 September and 7, 1955.Jews andArmenians living in the city and their businesses were also targeted in the pogrom, which was allegedly orchestrated by the Demokrat Parti-government ofTurkish Prime Minister Adnan Menderes . The events were triggered by the false news that the house inThessaloniki ,Greece , whereMustafa Kemal Atatürk was born in 1881, had been bombed the day before. [Güven, Dilek. “ [http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=163380 6–7 Eylül Olayları (1)] ,” "Radikal ", 6 September 2005 tr]A Turkish mob, most of which was trucked into the city in advance, assaulted Istanbul’s Greek community for nine hours. Although the orchestrators of the pogrom did not explicitly call for Greeks to be killed, between 13 and 16 Greeks (including two Orthodox

clerics ) and at least one Armenian died during or after the pogrom as a result of beatings andarson s.Speros Vryonis, Jr., "The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul", New York: [http://www.greekworks.com/ Greekworks.com] 2005, ISBN 978-0-9747660-3-4.] pnThirty-two Greeks were severely wounded. In addition, dozens of Greek women were raped, and a number of men were forcibly circumcised by the mob. 4,348 Greek-owned businesses, 110 hotels, 27 pharmacies, 23 schools, 21 factories, 73 churches and over a thousand Greek-owned homes were badly damaged or destroyed.pn The American consulate estimates that 59% of the businesses were Greek-owned, 17% were Armenian-owned, 12% were Jewish-owned, 10% were Muslim-owned; while 80% of the homes were Greek-owned, 9% were Armenian-owned, 3% were Jewish-owned, and 5% were Muslim-owned.

Estimates of the economic cost of the damage vary from Turkish government's estimate of 69.5 million

Turkish lira (equivalent to 24.8 millionUS$ [ [http://www.ceterisparibus.net/veritabani/1923_1990/doviz.htm#7 Turkish currency exchange rates 1923–1990] ] ), the British diplomat estimates of 100 millionGBP (about 200 millionUS$ ), theWorld Council of Churches ’ estimate of 150 millionUSD , and the Greek government's estimate of 500 millionUS$ .pnThe pogrom greatly accelerated

emigration of ethnic Greeks ( _tr. Rum) from the Istanbul region, reducing the 150,000-strong Greek minority in 1924 to about 2000. The number seems to be recovering since then, being over 5,000 in 2006. [According to figures presented by Prof. Vyron Kotzamanis to a conference of unions and federations representing the ethnic Greeks of Istanbul, the ethnic Greek population of Istanbul was then [July 2006] above the 5,000-person mark. [http://www.hri.org/news/greek/apeen/2006/06-07-02.apeen.html#03 "Ethnic Greeks of Istanbul convene"] , "Athens News Agency ", 2 July 2006.] Some see the pogrom as a continuation of a process ofTurkification that started with thedecline of the Ottoman Empire ,Ergil, Doğu. “ [http://www.turkishdailynews.com.tr/article.php?enewsid=23081 Past as present] ,” "Turkish Daily News " 12 September 2005.]Background

The Greeks of Istanbul

Constantinople (modernIstanbul ) was the capital of theByzantine Empire until 1453, when the city was conquered by Ottoman forces. A large Greek community continued to live in the city. The city’s Greek population, particularly thePhanariotes , came to play a significant role in the social and economic life of the city and in the political and diplomatic life of theOttoman Empire in general. This continued after the establishment of an independent Greek state in 1829, as well. A number of ethnic Greeks served in the Ottoman diplomatic service in the 19th century.Following the

Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) , the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, the forcible population exchange resulted in the uprooting of all Greeks in Turkey (and Turks in Greece) from where many of them had lived for centuries. But due to the Greeks' strong emotional attachment to their ancient capital as well as the importance of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for Greek and worldwide orthodoxy, the Greek population of Istanbul was specifically exempted and allowed to stay in place. Nevertheless, this population began to decline, as evidenced by demographic statistics.Punitive measures, such as the 1932 parliamentary law, barred Greek citizens living in Turkey from a series of 30 trades and professions from

tailoring andcarpentry tomedicine ,law andreal estate .pn The Wealthy Levy imposed in 1942 also served to reduce the economic potential of Greek businesspeople in Turkey.Context

The pogrom was triggered by Greece's appeal to the United Nations to demand self-determination for Cyprus. The British, who had the ruling mandate, urged both sides to find a peaceful solution to the

Cyprus dispute . Greek nationalists were attempting to forcibly pacify the Turkish Cypriot population, so the incumbent Democratic Party staged a show of force to convince the Greeks that annexation would ultimately fail, before the Tripartite London Conference starting on 29 August.cite journal

author = Kuyucu, Ali Tuna

year = 2005

title = Ethno-religious 'unmixing' of 'Turkey': 6-7 September riots as a case in Turkish nationalism

journal =Nations and Nationalism

volume = 11

issue = 3

pages = 361–380

doi = 10.1111/j.1354-5078.2005.00209.x]Since 1954, a number of nationalist student and

irredentist organizations, such as the National Federation of Turkish Students ( _tr. Türkiye Milli Talebe Federasyonu), the National Union of Turkish Students, and Hikmet Bilâ's (editor of the major newspaper "Hürriyet ") Cyprus is Turkish Party _tr. Kıbrıs Türktür Cemiyeti , had protested against the Greek minority and the Ecumenical Patriarchate.In 1955, a state-supported propaganda campaign involving the Turkish press galvanized public opinion against the Greek minority, targeting Athenogoras, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Phanar, in particular. Leading the pack was "

Hürriyet ", which wrote on 28 August 1955: "If the Greeks dare touch our brethren, then there are plenty of Greeks in Istanbul to retaliate upon." Ömer Sami Coşar from "Cumhuriyet " wrote on 30 August:Neither the Patriarchate nor the Rum minority ever openly supported Turkishnational interests when Turkey and Athens clashed over certain issues. In return,the great Turkish nation never raised its voice about this. But do the PhanarPatriarchate and our Rum citizens in Istanbul have special missions assigned byGreece in its plans to annex Cyprus? While Greece was crushing Turks in WesternThrace and was appropriating their properties by force, our Rum Turkish citizens livedas free as we do, sometimes even more comfortably. We think that these Rums, whochoose to remain silent in our struggle with Greece, are clever enough not to fall intothe trap of four or five provocateurs.

"Tercüman", "Yeni Sabah", and "Gece Postası" followed suit. In the weeks running up to September 6, Turkish leaders made a number of anti-Greek speeches. On August 28 Prime Minister Menderes claimed that Greek Cypriots were planning a massacre of Turkish Cypriots. In addition to the

Cyprus issue , the chronic economic situation also motivated the Turkish political leadership into orchestrating the pogrom. Although a minority, the Greek population played a prominent role in the city’s business life, making it a convenientscapegoat during the economic crisis in the mid-50s which saw Turkey's economy contract (with an 11% GDP/capita decrease in 1954). The DP responded first with inflationary policies, then when that failed, with authoritarianism and populism. DP's policies also introduced rural-urban mobility, which exposed some of the rural population to the lifestyles of the urban minorities. The three chief destinations were the largest three cities: Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. Between 1945-1955, the population of Istanbul increased from 1 million to about 1.6 million. Many of these new residents found themselves in shantytowns ( _tr. gecekondus), and constituted a prime target for populist policies.The riots were sparked by an alleged bomb planted at the Turkish consulate (and birth place of Atatürk) in Greece’s second largest city,

Thessaloniki .The Pogrom

Planning

The 1961

Yassıada Trial against Menderes and Foreign MinisterFatin Rüştü Zorlu exposed the proximate planning of the pogrom. Menderes and Zorlu mobilized the formidable machinery of the ruling Demokrat Parti (DP) and party-controlled trade unions of Istanbul. Interior ministerNamik Gedik was also involved. According to Zorlu's lawyer at the Yassiada trial, a mob of 300,000 was marshalled in a radius of convert|40|mi|km|-1 around the city for the pogrom.pnThe trial also revealed that the fuse for the consulate bomb was sent from Turkey to Thessaloniki on 3 September. Oktay Engin, the twenty-year-old National Security Service agent, who was then in Thessaloniki under the cover of a law student, was given the mission of installing the explosives. [cite news|url=http://www.turkishdailynews.com.tr/article.php?enewsid=23080

accessdate=2008-09-21

title=Sept. 6-7, 1955, in Greek Media

work=Turkish Daily News

date=2005-09-12

first=Ariana

last=Ferentinou]In addition, ten of Istanbul’s 18 branches of Cyprus is Turkish Party were run by DP officials. This organization played a crucial role in inciting anti-Greek activities.pn

In his 2005 book, Speros Vryonis documents the direct role of the Demokrat Parti organization and government-controlled trade unions in amassing the rioters that swept Istanbul. Most of the rioters came from western

Asia Minor . His case study ofEskişehir shows how the party there recruited 400 to 500 workers from local factories, who were carted by train with third class-tickets to Istanbul. These recruits were promised the equivalent ofUS$ 6, which was never paid. They were accompanied by Eskişehirpolice , who were charged with coordinating the destruction and looting once the contingent was broken up into sub-groups of 40–50 men, and the leaders of the party branches.pnWhile the DP took the blame for the events, it was recently revealed that the pogrom was in actuality a product of the Turkish

deep state 'sspecial force s. Four star general Sabri Yirmibeşoğlu, the right-hand man of General Kemal Yamak [cite news|url=http://www.milliyet.com.tr/2006/01/08/yazar/dundar.html

work=Milliyet

first=Can

last=Dündar

accessdate=2008-09-21

title=Özel Harp'çinin tırmanış öyküsü

date=2007-04-01

language=Turkish] who led the Turkish outpost ofOperation Gladio under the title of the Special Warfare Department ( _tr. Özel Harp Dairesi), proudly reminisced about his involvement in the pogrom, calling it "a magnificent organization".cite news|url=http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/yazarAd.do?kn=85

accessdate=2008-09-21

first=Doğu

last=Ergil

title=The dark side of nationalism: Sept. 6-7 incident

work=Today's Zaman

date=2008-09-17] cite news|url=http://www.taraf.com.tr/yazar.asp?mid=1821

accessdate=2008-09-21

title=6-7 Eylül’de devletin ‘muhteşem örgütlenmesi’

work=Taraf

date=2008-09-07

first=Ayşe

last=Hür

language=Turkish]Execution

Municipal and government trucks were placed in strategic points all around the city to distribute the tools of destruction; shovels, pickaxes, crowbars, ramrods and petrol; while 4,000 private taxis were requisitioned to transport the perpetrators.pn

A protest rally on the night of September 6, organized by the authorities in Istanbul, on the Cyprus issue and the alleged

arson attack in Thessaloniki at the house where Atatürk was born, was the cover for amassing the rioters. At 13:00, news reports of the bombing were announced by radio. After noon, the daily "İstanbul Ekspres", which was associated with the DP and the National Security Service, repeated the news in print. According to Mihail Vasiliadis, the accompanying photographs were allegedly seen by Salonican photographer Mr. Kiryakidis on September 3 (three days before the actual bombing), who had been asked by the consulate's wife to promptly develop them. It was later learned that the paper had been tipped off about the event, and prepared by stocking enough paper to print 300,000 copies. At 17:00, the pogrom started and from its original centre inTaksim Square , the trouble rippled out during the evening through the old suburb of Pera, the smashing and looting of Greek commercial property, particularly along Yuksek Kaldirim street. By six o'clock at night, many of the Greek shops on Istanbul's main shopping street,Istiklal Caddesi , were ransacked. Many commercial streets were littered with merchandise and fittings torn out of Greek-owned businesses.According to the eyewitness account of a Greek dentist, the mob chanted "Death to the Gavurs" ( _en. infidels), "Massacre the Greek traitors", "Down with

Europe " and "Onward toAthens and Thessaloniki" as they executed the pogrom.The riot died down by midnight with the intervention of the

Turkish Army and martial law was declared. Eyewitnesses reported, however, that army officers and policemen had earlier participated in the rampages and in many cases urged the rioters on.Personal violence

While the pogromists were not instructed to kill their targets, sections of the mob went much further than scaring or intimidating local Greeks. Between 13 and 16 Greeks and one Armenian (including two clerics) died as a result of the pogrom. 32 Greeks were severely wounded. Men and women were

rape d, and according to the account of the Turkish writerAziz Nesin , men, mainly priests, were subjected to forcedcircumcision by frenzied members of the mob and an Armenianpriest died after the procedure. Nesin wrote:Material damage

The physical and material damage was considerable and over 4,348 Greek-owned businesses, 110 hotels, 27 pharmacies, 23 schools, 21 factories, and 73 churches and over 1,000 Greek-owned homes were badly attacked or destroyed.

Church property

In addition to commercial targets, the mob clearly targeted property owned or administered by the Greek Orthodox Church. 73 churches and 23 schools were vandalized, burned or destroyed, as were 8 asperses and 3

monasteries . This represented about 90 percent of the church property portfolio in the city. The ancient Byzantine church ofPanagia in Veligradiou was vandalised and burned down. The church at Yedikule was badly vandalised, as was the church of St. Constantine ofPsammathos . AtZoodochos Pege church inBalıklı , the tombs of a number of ecumenical patriarchs were smashed open and desecrated. Theabbot of the monastery, Bishop Gerasimos ofPamphilos , was severely beaten during the pogrom and died from his wounds some days later in Balıklı Hospital. In one church arson attack, Father Chrysanthos Mandas was burned alive. The Metropolitan ofLiloupolis , Gennadios, was badly beaten and went mad. Elsewhere in the city, Greekcemeteries came under attack and were desecrated. Some reports also testified thatrelic s of saints were burned or thrown to dogs.Witnesses

An eyewitness account was provided by journalist

Noel Barber of theLondon "Daily Mail " on 14 September 1955:On the occasion of the pogrom's 50th anniversary, a seventy-year-old Mehmet Ali Zeren said, "I was in the street that day and I remember very clearly...In a jewelry store, one guy had a hammer and he was breaking pearls one by one."

One significant eyewitness was

Ian Fleming , theJames Bond author, who was in Istanbul covering theInternational Police Conference as a special representative for the London "Sunday Times". His account, entitled "The Great Riot of Istanbul", appeared in that paper on 11 September 1955.For some Turkish eyewitness accounts, read Ayşe Hür's article in "Taraf".

Secondary action

While the pogrom was predominantly an Istanbul affair, there were some outrages in other Turkish cities. On the morning of 7 September 1955 In

İzmir (Smyrna ), a mob overran the İzmir National Park, where an international exhibition was taking place, and burned the Greek pavilion. Moving next to the Church of Saint Fotini, built two years earlier to serve the needs of the Greek officers (serving atNATO Regional Headquarters), the mob destroyed it completely. The homes of the few Greek families and officers were then looted.Documentation

Considerable contemporary documentation showing the extent of the destruction is provided by the photographs taken by

Demetrios Kaloumenos , then official photographer of theEcumenical Patriarchate . Setting off just hours after the pogrom began, Kaloumenos set out with his camera to capture the damage and smuggled the film to Greece.Reactions

The Menderes government attempted to blame Turkish Communists for the pogrom, arresting 45 "card-carrying communists" (including

Aziz Nesin ,Kemal Tahir , and İlhan Berktay), only to free them four months later. Foreign observers knew better; in a letter of 15 November 1955 to prime minister Menderes, Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras graphically described the crimes inflicted on his flock. “The very foundation of a civilisation which is the heritage of centuries, the property of all mankind, has been gravely attacked”, he wrote, adding: “All of us, without any defence, spent moments of agony, and in vain sought and waited for protection from those responsible for order and tranquillity.”The

chargé d’affaires at theBritish Embassy inAnkara ,Michael Stewart , directly implicated Menderes’ Demokrat Parti in the execution of the attack. “There is fairly reliable evidence that local Demokrat Parti representatives were among the leaders of the rioting in various parts of Istanbul, notably in the Marmara islands, and it has been argued that only the Demokrat Parti had the political organisation in the country capable of demonstrations on the scale that occurred,” he reported, refusing to assign blame to the party as a whole or Menderes personally, however.Although British ambassador to Ankara, Bowker, advised British Foreign Secretary

Harold Macmillan that the United Kingdom should “court a sharp rebuff by admonishing Turkey”, only a note of distinctly mild disapproval was dispatched to Menderes.Holland, Robert. " [http://books.google.com/books?id=HI4nxW6ffCEC&pg=PA76&dq=%22court+a+sharp+rebuff+by+admonishing+Turkey%22&ei=SIjWSMCPNoaCjwGt7qHnDg&client=firefox-a&sig=ACfU3U3rsICQ4Z0Zv3ZxTVTEB0I1xbkugA The Struggle for Mastery, 4 October 1955–9 March 1956] ," "Britain and the Revolt in Cyprus, 1954–59", Oxford:Clarendon Press , 1998, pp. 75–77.] The context of theCold War led Britain and the U.S. to absolve the Menderes government of the direct political blame that it was due. The efforts of Greece to internationalize the human rights violations through international organizations such as theUN andNATO found little sympathy. British NATO representative Cheetham deemed it “undesirable” to probe the pogrom. US representativeEdwin Martin thought the effect on the alliance was exaggerated, and the French,Belgians andNorwegians urged the Greeks to “let bygones be bygones”. Indeed, theNorth Atlantic Council issued a statement that the Turkish government had done everything that could be expected.More outspoken was the

World Council of Churches , given the damage wrought on 90 percent of Istanbul’s Greek Orthodox churches, and a delegation was sent to Istanbul to inspect the havoc.Fact|date=September 2008Aftermath

As private

insurance did not exist in Turkey at the time, the only hope the pogrom's victims had for compensation was from the Turkish state. Although Turkish PresidentCelal Bayar announced that “the victims of the destruction shall be compensated”, there was little political will or financial means to carry out such a promise. In the end, Greeks ended up receiving about 20 percent of their claims due to the fact that the assessed values of their properties had already been vastly reduced.Tensions continued and in 1958–1959, Turkish nationalist students embarked on a campaign encouraging the boycott of all Greek businesses. The task was completed eight years later in 1964 when the Ankara government reneged on the 1930 Greco-Turkish Ankara Convention, which established the right of Greek "etablis" (Greeks who were born and lived in Istanbul but held Greek

citizenship ) to live and work in Turkey. Around 12,000 [ [http://www.euborderconf.bham.ac.uk/publications/files/WP17_Turkey-Greece.pdf The European Union and Border Conflicts: The EU and Cultural Change in Greek-Turkish Relations] ] ethnic Greeks without Turkish citizenship weredeported from Turkey with two day's notice, and the Greek community of Istanbul shrunk from 80,000 (or 100,000 by some accounts) persons in 1955 to only 48,000 in 1965. Today, the Greek community numbers about 5,000, mostly older, Greeks.Fact|date=September 2008After the military coup of 1960, Menderes and Zorlu were charged, at the Yassiada Trial in 1960–61, with violating the constitution. The trial also made reference to the pogrom, for which they were blamed. While the accused were denied fundamental rights regarding their defence, they were found guilty and sentenced to death by

hanging .The military prosecutor at the time kept documents and photographs of the event in order to educate future generations. He entrusted the

Turkish Historical Society with them, stipulating that they be exhibited 25 years after his death. When the date passed and the documents were exhibited in 2005, a group of ultranationalist "Ülküculer" raided and defaced the exhibitVick, Karl. “ [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/09/29/AR2005092902240.html In Turkey, a Clash of Nationalism and History] ”, "Washington Post ", 30 September 2005.] by hurling eggs at the photographs and trampling over them. [cite news|url=http://bianet.org/english/kategori/english/109807/eleven-taken-into-custody-for-ergenekon-investigation

accessdate=2008-09-21

title=Eleven Taken Into Custody For Ergenekon Investigation

date=2008-09-18

author=BÇ/EÜ

work=Bianet]Oktay Engin, the agent who attempted the arson in Salonica, had continued to work at MİT for years until 1992 when he was promoted to the office of governor for

Nevşehir Province , denying any responsibility all the while. [cite journal|url=http://www.aksiyon.com.tr/detay.php?id=2942

accessdate=2008-09-21

journal=Aksiyon

title=Bombacı da, MIT elemanı da değildim

date=2003-09-08

language=Turkish

volume=457

first=Faruk

last=Mercan]In August 1995, the

US Senate passed a special resolution marking the September 1955 pogrom, calling on thePresident of the United States Bill Clinton to proclaim 6 September as a Day of Memory for the victims of the pogrom.Fact|date=September 2008ee also

*

Foreign relations of Turkey References

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.