- Albigensian Crusade

-

Albigensian Crusade Part of the Crusades

Political map of Languedoc on the eve of the Albigensian CrusadeDate 1209–1229 Location Languedoc, France Belligerents Crusaders

Kingdom of France

Kingdom of FranceCathars

Counts of Toulouse

Counts of Toulouse

Crown of Aragon

Crown of AragonCommanders and leaders  Simon de Montfort†

Simon de Montfort†

Philip II of France

Philip II of France

Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII of France Raymond Roger Trencavel

Raymond Roger Trencavel

Raymond VI of Toulouse

Raymond VI of Toulouse

Peter II of Aragon†

Peter II of Aragon†- Reconquista

- Sardinian

- Mahdia

- First

- People's

- 1101

- Norwegian

- Balearic

- Wendish

- Second

- First Swedish

- Third

- 1197

- Livonian

- Fourth

- Albigensian

- Children's

- Fifth

- Sixth

- Prussian

- Second Swedish

- Seventh

- Eighth

- Ninth

- Aragonese

- Third Swedish

- Smyrniote

- Alexandrian

- Savoyard

- Despenser's

- Barbary

- Nicopolis

- Varna

- Otranto

- Lepanto

- Armada

Book:The Crusades

Book:The Crusades Portal:Crusades

Portal:Crusades

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French and promptly took on a political flavour, resulting in not only a significant reduction in the number of practicing Cathars but also a realignment of Occitania, bringing it into the sphere of the French crown and diminishing the distinct regional culture and high level of Aragonese influence.

When Innocent III's diplomatic attempts to roll back Catharism[1] met with little success and after the papal legate Pierre de Castelnau was murdered, Innocent III declared a crusade against Languedoc, offering the lands of the Cathar heretics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms. The violence led to France's acquisition of lands with closer linguistic, cultural, and political ties to Catalonia (see Occitan).

The Albigensian Crusade also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Dominican Order and the Medieval Inquisition.

Contents

Origin

The Catholic Church had always dealt sternly with strands of Christianity that it considered heretical, but before the 12th century these tended to centre around individual preachers or small localised sects. By the 12th century, more organized groups such as the Waldensians and Cathars were beginning to appear in the towns and cities of newly urbanized areas. In Western mediterranean France, one of the most urbanized areas of Europe at the time, the Cathars grew to represent a popular mass movement[2] and the belief was spreading to other areas. Relatively few believers took the consolamentum to become full Cathars, but the faith attracted many followers and sympathisers.

The Cathari were thought to be dualistic, believing not in one all-encompassing god, but in two, equal and comparable in status, but their theology and cosmological perception and teaching remains unknown, as no known source has survived that can elucidate this. Through secondary sources we learn that they held that the physical world was evil and created by Rex Mundi (Latin, "King of the World"), who encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful; the second god, the one whom they worshipped, was entirely disincarnate: a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the god of love, order and peace. The Catholic Church, alarmed by the spread of Cathar teachings, perceived the movement as a well-organised opponent on a scale that had not been seen since the days of Arianism and Marcionism.

This Pedro Berruguete work of the 15th century depicts a story of Saint Dominic and the Albigensians, in which the texts of each were cast into a fire, but only Saint Dominic's proved miraculously resistant to the flames.

This Pedro Berruguete work of the 15th century depicts a story of Saint Dominic and the Albigensians, in which the texts of each were cast into a fire, but only Saint Dominic's proved miraculously resistant to the flames.

Deriving from earlier varieties of gnosticism, Cathar theology found its most spectacular success in the Languedoc and the Cathars were known as Albigensians, either because of an association with the city of Albi, or because the 1176 Church Council which declared the Cathar doctrine heretical was held near Albi.[3][4] In Languedoc, political control was divided among many local lords and town councils.[5] Before the crusade, there was little fighting in the area and a fairly sophisticated polity. Western Mediterranean France itself was at that time divided between the Crown of Aragon and the county of Toulouse.

On becoming Pope in 1198, Innocent III resolved to deal with the Cathars. The Cathars were not under the authority of the Catholic Church, and so initially preachers were sent out to return the schismatics to the Roman communion. Attempts at peaceful conversion met with little success.[6] Even St. Dominic, acting more independently, only achieved a handful of conversions.[7] The Cathar leadership was protected by powerful nobles,[8] and some bishops, allegedly resentful of papal authority in their sees, were not hostile toward the belief. In 1204 the Pope suspended the authority of some of those bishops[9] and appointed papal legates to act in his name.[10] In 1206 he sought support for wider action against the Cathars from the nobles of Languedoc.[11] Noblemen who supported Catharism were excommunicated.

The powerful count Raymond VI of Toulouse refused to assist and was excommunicated in May 1207. The Pope called upon the French king, Philippe II, to act against those nobles who permitted Catharism, but Philippe declined to act. Count Raymond met with the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in January 1208,[12] and after an angry meeting, Castelnau was murdered the following day.[13] The Pope reacted to the murder by issuing a bull declaring a crusade against Languedoc – offering the land of the heretics to any who would fight. This offer of land drew the northern French nobility into conflict with the nobles of the south.[14]

Military campaigns

The military campaigns of the Crusade can be divided into several periods: the first from 1209 to 1215 was a series of great successes for the crusaders in Languedoc. There was episodes of extreme violence like the killing of Béziers, faced the forces assembled by vassal lords of the Capetian mainly from Ile de France and the north of France, led by Simon de Montfort, against the nobility of Toulouse led by Count Raymond VI of Toulouse and the family Trencavel that, as allies and vassals of the king of Aragon Peter II the Catholic, invoked direct involvement in the conflict at the Aragonese monarch, who was defeated and killed in the course of Battle of Muret in 1213.

The captured lands, however, were largely lost between 1215 and 1225 in a series of revolts and military reverses. The death of Simon de Montfort at the site to Toulouse after the return of Count Raymond VII of Toulouse and the consolidation of Occitan resistance supported by the Count of Foix and Aragonese crown forces decided the military intervention of Louis VIII of France from 1226 with the support of Pope Honorius III.

The situation turned again following the intervention of the French king, Louis VIII, in 1226. He died in November of that year, but the struggle continued under King Louis IX and the area was reconquered by 1229; the leading nobles made peace, culminating in the Treaty of Meaux-Paris in 1229, which was agreed the integration of the territory Occitan in the French crown. After 1233, the Inquisition was central to crushing what remained of Catharism. Resistance and occasional revolts continued, but the days of Catharism were numbered. Military action ceased in 1255.

Initial success 1209 to 1215

By mid 1209, around 10,000 crusaders had gathered in Lyon before marching south.[15] In June, Raymond of Toulouse, recognizing the disaster at hand, finally promised to act against the Cathars, and his excommunication was lifted.[16] The crusaders turned towards Montpellier and the lands of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel, aiming for the Cathar communities around Albi and Carcassonne. Like Raymond of Toulouse, Raymond-Roger sought an accommodation with the crusaders, but he was refused a meeting and raced back to Carcassonne to prepare his defences.[17]

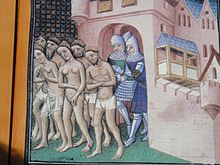

Cathars being expelled from Carcassonne in 1209.

In August 1209 the crusaders captured the small village of Servian and headed for Béziers, arriving on July 21. They invested the city, called the Catholics within to come out, and demanded that the Cathars surrender.[18] Both groups refused. The city fell the following day when an abortive sortie was pursued back through the open gates.[19] The entire population was slaughtered and the city burned to the ground. Contemporary sources give estimates of the number of dead ranging between fifteen and sixty thousand. The latter figure appears in the Papal Legate Arnaud-Amaury's report to the Pope.[20] The news of the disaster quickly spread and afterwards many settlements surrendered without a fight.

The next major target was Carcassonne. The city was well fortified, but vulnerable, and overflowing with refugees.[21] The crusaders arrived on August 1, 1209. The siege did not last long.[22] By August 7 they had cut the city's water supply. Raymond-Roger sought negotiations but was taken prisoner while under truce, and Carcasonne surrendered on August 15.[23] The people were not killed, but were forced to leave the town — naked according to Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay. "In their shifts and breeches" according to another source. Simon de Montfort now took charge of the Crusader army,[24] and was granted control of the area encompassing Carcassonne, Albi, and Béziers. After the fall of Carcassonne, other towns surrendered without a fight. Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Fanjeaux, Limoux, Lombers and Montréal all fell quickly during the autumn.[25] However, some of the towns that had surrendered later revolted.

The next battle centred around Lastours and the adjacent castle of Cabaret. Attacked in December 1209, Pierre-Roger de Cabaret repulsed the assault.[26] Fighting largely halted over the winter, but fresh crusaders arrived.[27] In March 1210, Bram was captured after a short siege.[28] In June the well-fortified city of Minerve was invested.[29] It withstood a heavy bombardment, but in late June the main well was destroyed, and on July 22, the city surrendered.[30] The Cathars were given the opportunity to return to Catholicism. Most did. The 140 who refused were burned at the stake.[31] In August the crusade proceeded to the stronghold of Termes.[32] Despite sallies from Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, the siege was solid, and in December the town fell.[33] It was the last action of the year.

When operations resumed in 1211 the actions of Arnaud-Amaury and Simon de Montfort had alienated several important lords, including Raymond de Toulouse,[34] who had been excommunicated again. The crusaders returned in force to Lastours in March and Pierre-Roger de Cabaret soon agreed to surrender. In May the castle of Aimery de Montréal was retaken; he and his senior knights were hanged, and several hundred Cathars were burned.[35] Cassès[36] and Montferrand[37] both fell easily in early June, and the crusaders headed for Toulouse.[38] The town was besieged, but for once the attackers were short of supplies and men, and so Simon de Montfort withdrew before the end of the month.[39] Emboldened, Raymond de Toulouse led a force to attack Montfort at Castelnaudary in September.[40] Montfort broke free from the siege[41] but Castelnaudary fell and the forces of Raymond went on to liberate over thirty towns[42] before the counter-attack ground to a halt at Lastours, in the autumn. The following year much of the province of Toulouse was captured by Catholic forces.[43]

In 1213, forces led by King Peter II of Aragon, came to the aid of Toulouse.[44] The force besieged Muret,[45] but in September a sortie from the castle led to the death of King Peter,[46] and his army fled. It was a serious blow for the resistance, and in 1214 the situation became worse: Raymond was forced to flee to England,[47] and his lands were given by the Pope to the victorious Philippe II,[citation needed] a stratagem which finally succeeded in interesting the king in the conflict. In November the always active Simon de Montfort entered Périgord[48] and easily captured the castles of Domme[49] and Montfort;[50] he also occupied Castlenaud and destroyed the fortifications of Beynac.[51] In 1215, Castelnaud was recaptured by Montfort,[52] and the crusaders entered Toulouse. Toulouse was gifted to Montfort.[53] In April 1216 he ceded his lands to Philippe.

The yellow cross worn by Cathar repentants.

Revolts and reverses 1216 to 1225

However, Raymond, together with his son, returned to the region in April 1216 and soon raised a substantial force from disaffected towns. Beaucaire was besieged in May and fell after a three month siege; the efforts of Montfort to relieve the town were repulsed. Montfort had then to put down an uprising in Toulouse before heading west to captured Bigorre, but he was repulsed at Lourdes in December 1216. In September 1217, while Montfort was occupied in the Foix region, Raymond re-took Toulouse. Montfort hurried back, but his forces were insufficient to re-take the town before campaigning halted. Montfort renewed the siege in the spring of 1218. While attempting to fend off a sally by the defenders, Montfort was struck and killed by a stone hurled from defensive siege equipment. Popular accounts state that the city's artillery was operated by the women and girls of Toulouse.

Innocent III died in July 1216; and with Montfort now dead, the crusade was left in temporary disarray. The command passed to the more cautious Philippe II, who was more concerned with Toulouse than heresy. The crusaders had taken Belcaire and besieged Marmande in late 1218 under Amaury de Montfort, son of the late Simon. While Marmande fell on June 3, 1219, attempts to retake Toulouse failed, and a number of Montfort holds also fell. In 1220, Castelnaudary was re-taken from Montfort. He reinvested the town in July 1220, but it withstood an eight month siege. In 1221, the success of Raymond and his son continued: Montréal and Fanjeaux were re-taken, and many Catholics were forced to flee. In 1222, Raymond died and was succeeded by his son, also named Raymond. In 1223, Philippe II died and was succeeded by Louis VIII. In 1224, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carcassonne. The son of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel returned from exile to reclaim the area. Montfort offered his claim to the lands of Languedoc to Louis VIII, who accepted.

French royal intervention

In November 1225, at a Council of Bourges, Raymond, like his father, was excommunicated. The council gathered a thousand churchmen to authorize a tax on their annual incomes, the "Albigensian tenth", to support the Crusade, though permanent reforms intended to fund the papacy in perpetuity foundered.[54] Louis VIII headed the new crusade into the area in June 1226. Fortified towns and castles surrendered without resistance. However, Avignon, nominally under the rule of the German emperor, did resist, and it took a three-month siege to finally force its surrender that September. Louis VIII died in November and was succeeded by the child king Louis IX. But Queen regent Blanche of Castile allowed the crusade to continue under Humbert de Beaujeu. Labécède fell in 1227 and Vareilles and Toulouse in 1228. However, Queen Blanche offered Raymond a treaty: recognizing him as ruler of Toulouse in exchange for his fighting Cathars, returning all Church property, turning over his castles and destroying the defenses of Toulouse. Moreover, Raymond had to marry his daughter Jeanne to Louis' brother Alphonse, with the couple and their heirs obtaining Toulouse after Raymond's death, and the inheritance reverting to the king in case they did not have issue, as actually happened. Raymond agreed and signed the Treaty of Paris at Meaux on April,12 1229. He was then seized, whipped and briefly imprisoned.

Inquisition

The Languedoc now was firmly under the control of the King of France. The Inquisition was established in Toulouse in November 1229, and the process of ridding the area of Cathar belief and investing its remaining strongholds began. Under Pope Gregory IX the Inquisition was given great power to suppress the heresy. Contrary to popular legend, the Inquisition proceeded largely by means of legal investigation persuasion and reconciliation. Judicial procedures were used and although the accused were not allowed to know the names of their accusers, they were permitted to mount a defence. The vast majority found guilty of heresy were given light penalties. 11 percent of offenders faced prison. Only around 1 percent, the most steadfast and relapsed Cathars were handed over to the secular authority to face burning at the stake.[55] Some bodies were, however, exhumed for burning. Many still resisted, taking refuge in fortresses at Fenouillèdes and Montségur, or inciting small uprisings. In 1235, the Inquisition was forced out of Albi, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Raymond-Roger de Trencavel led a military campaign in 1240, but was defeated at Carcassonne in October, then besieged at Montréal. He soon surrendered and was exiled to Aragon. In 1242, Raymond of Toulouse attempted to revolt in conjunction with an English invasion, but the English were quickly repulsed and his support evaporated. He was subsequently pardoned by the king.

Cathar strongholds fell one by one. Montségur withstood a nine-month siege before being taken in March 1244. The final hold-out, a small, isolated, overlooked fort at Quéribus, quickly fell in August 1255. The last known burning of a person who professed Cathar beliefs occurred in Corbières, in present-day Switzerland, in 1321.[56]

Notes

- ^ VC Introduction: The historical background

- ^ VC §5

- ^ Mosheim, Johann Lorenz. Mosheim's Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern 385 (W. Tegg 1867) [1]

- ^ See also the Third Lateran Council, 1179

- ^ cf Graham-Leigh

- ^ VC §6

- ^ PL §VIII

- ^ VC §8-9

- ^ PL §VI

- ^ PL §VII

- ^ PL §IX

- ^ VC §55-58

- ^ VC §59-60, PL §IX

- ^ It should be remembered that the weakness of King John was already well on the way to destroying the Angevin Empire before the Battle of Bouvines ended it completely.

- ^ VC §84

- ^ PL §XIII

- ^ VC §88

- ^ VC §89

- ^ VC §90-91

- ^ According to the Cistercian writer Caesar of Heisterbach, one of the leaders of the Crusader army, the Papal legate Arnaud-Amaury, when asked by a Crusader how to distinguish the Cathars from the Catholics, answered: "Caedite eos! Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius" – "Kill them [all]! Surely the Lord discerns which [ones] are his". On the other hand, the legate's own statement, in a letter to the Pope in August 1209 (col.139), states:

while discussions were still going on with the barons about the release of those in the city who were deemed to be Catholics, the servants and other persons of low degree and unarmed attacked the city without waiting for orders from their leaders. To our amazement, crying "to arms, to arms!", within the space of two or three hours they crossed the ditches and the walls and Béziers was taken. Our men spared no one, irrespective of rank, sex or age, and put to the sword almost 20,000 people. After this great slaughter the whole city was despoiled and burnt, as Divine vengeance miraculously...

- ^ VC §92-93

- ^ VC §94-96, PL §XIV

- ^ VC §98

- ^ VC §101

- ^ VC §108-113

- ^ VC §114

- ^ VC §115-140

- ^ VC §142

- ^ VC §151

- ^ VC §154

- ^ VC §156

- ^ VC §168

- ^ VC §169-189

- ^ VC §194

- ^ VC §215

- ^ VC §233 PL §XVII

- ^ VC §235

- ^ VC §239

- ^ VC §243

- ^ VC §253-265

- ^ VC §273-276, 279

- ^ VC §266, 278

- ^ VC §286-366, PL §XVOO

- ^ VC §367-446

- ^ VC §447-484, PL §XX

- ^ VC §463, PL §XXI

- ^ PL §XXV

- ^ VC §528-534

- ^ VC §529

- ^ VC §530

- ^ VC §533-534

- ^ VC §569

- ^ VC §554-559, 573

- ^ Richard Kay, The Council of Bourges, 1225: A Documentary History (Brookfield, Vermont: Ashgate) 2002.

- ^ Christopher Tyerman, God's war: a new history of the Crusades, 2006, p 602

- ^ Website of Stephen O'Shea The victim was the Cathar Perfect, William Beliaste.

References

- VC: Sibly, W. A. and M. D., translators (1998), The history of the Albigensian Crusade: Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay's Historia Albigensis, Woodbridge: Boydell, ISBN 0851158072

- CCA: Martin-Chabot, Eugène, editor and translator (1931-1961), La Chanson de la Croisade Albigeoise éditée et traduite, Paris: Les Belles Lettres. His occitan text is in the Livre de Poche (Lettres Gothiques) edition, which uses the Gougaud 1984 translation for its better poetic style.

- PL: Duvernoy, Jean, editor (1976), Guillaume de Puylaurens, Chronique 1145-1275: Chronica magistri Guillelmi de Podio Laurentii, Paris: CNRS, ISBN 2910352064. Text and French translation. Reprinted: Toulouse: Le Pérégrinateur, 1996.

- Sibly, W.A. and Sibly, M.D., translators, The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath, Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge, 2003, ISBN 0851159257

Further reading

- Barber, Malcolm (2000). The Cathars: Christian Dualists in the Middle Ages. Harlow.

- Graham-Leigh, Elaine (2005). The Southern French Nobility and the Albigensian Crusade. Boydell. ISBN 1843831295.

- LeRoy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1978). Montaillou, an Occitan Village 1294-1324. Penguin. ISBN 0-140-05471-5.

- Mann, Judith (2002). The Trail of Gnosis: A Lucid Exploration of Gnostic Traditions. Gnosis Traditions Press. ISBN 1-434814-32-7.

- Strayer, Joseph R (1971; reprinted 1992). The Albigensian Crusades. The University of Michigan Press.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1978). The Albigensian Crusade. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-11064-9.

- Weis, René (2001). The Yellow Cross, the Story of the Last Cathars 1290-1329. Penguin. ISBN 0-140-27669-6.

- Pegg, Mark (2008). A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517131-0.

External links

- Albigensian Crusade

- The paths of Cathars by the philosopher Yves Maris.

- The Crusades Wiki

- The english website of the castle of Termes, besieged in 1210

- The Forgotten Kingdom - The Albigensian Crusade - La Capella Reial - Hespèrion XXI, dir. Jordi Savall

Categories:- Catharism

- Albigensian Crusade

- Massacres in France

- Wars involving the Crown of Aragon

- 13th century in Europe

- 13th century in France

- 13th-century crusades

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.