- Christianity in the 8th century

-

Main article: History of medieval Christianity

Contents

Eastern Church

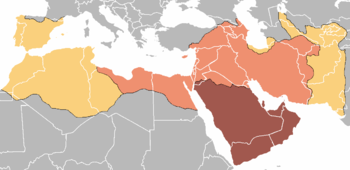

By the late 8th century the Muslim empire had conquered all of Persia and much of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) territory including Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. Suddenly much of the Christian world was under Muslim rule. Over the coming centuries the Muslim nations became some of the most powerful in the Mediterranean basin.

Though the Roman Church had claimed religious authority over Christians in Egypt and the Levant, in reality the majority of Christians in these regions were miaphysites and other sects that had long been persecuted by Constantinople.

Second Council of Nicea: Iconoclasts and Iconophiles

Main article: Iconoclasm (Byzantine)Resolved under the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Iconoclasm was a movement within the Eastern Christian Byzantine church to establish that the Christian culture of portraits (see icon) of the family of Christ and subsequent Christians and biblical scenes were not of a Christian origin and therefore heretical.[1] There were two periods of Iconoclasm 730-787 and 813-843. This movement itself was later defined as heretical under the Seventh Ecumenical council. The group destroyed much of the Christian churches' art history, which is needed in addressing the traditional interruptions of the Christian faith and the artistic works that in the early church were devoted to Jesus Christ or God. Many Glorious works were destroyed during this period.[2]

Iconoclasm as a movement began within the Eastern Christian Byzantine church in the early 8th century, following a series of heavy military reverses against the Muslims. Sometime between 726–730 the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian ordered the removal of an image of Jesus prominently placed over the Chalke gate, the ceremonial entrance to the Great Palace of Constantinople, and its replacement with a cross. This was followed by orders banning the pictorial representation of the family of Christ, subsequent Christian saints, and biblical scenes. In the West, Pope Gregory III held two synods at Rome and condemned Leo's actions. In Leo's realms, the Iconoclast Council of Hieria, in 754, ruled that the culture of holy portraits (see icon) was not of a Christian origin and therefore heretical.[1] The movement destroyed much of the Christian church's early artistic history, to the great loss of subsequent art and religious historians. The iconoclastic movement itself was later defined as heretical in 787 under the Seventh Ecumenical council, but enjoyed a brief resurgence between 815 and 842.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council was called under the Empress Regnant Irene in 787, known as the second of Nicaea. It affirmed the making and veneration of icons, while also forbidding the worship of icons and the making of three-dimensional statuary. It reversed the declaration of an earlier council that had called itself the Seventh Ecumenical Council and also nullified its status (see separate article on Iconoclasm). That earlier council had been held under the iconoclast Emperor Constantine V. It met with more than 340 bishops at Constantinople and Hieria in 754, declaring the making of icons of Jesus or the saints an error, mainly for Christological reasons.

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not recognize as dogma any ecumenical councils other than these seven.[3] Orthodox thinking differs on whether the Fourth and Fifth Councils of Constantinople were properly Ecumenical Councils, but the majority view is that they were merely influential rather than dogmatic and therefore not binding.[citation needed]

Two prototypes of icons would be the Christ Pantocrator and the Icon of the Hodegetria. In the West the tradition of icons have been seen as the veneration of "graven images" or against "no graven images" as noted in Exodus 20:4. From the Orthodox point of view graven then would be engraved or carved. Thus this restriction would include many of the ornaments that Moses was commanded to create in the passages right after the commandment was given i.e. the carving of cherubim Exodus 26:1. The commandment as understood by such out of context interpretation would mean "no carved images". This would include the cross and other holy artifacts. The commandment in the East is understand that the people of God are not to create idols and then worship them. It is "right worship" to worship which is of God, which is Holy and that alone.[4]

John of Damascus

In the Roman Catholic Church, St. John of Damascus, who lived in the 8th century, is generally considered to be the last of the Church Fathers and at the same time the first seed of the next period of church writers, scholasticism.

Iconoclasts and iconophiles

- Patriarch Germanus I of Constantinople (patriarch 715-730)

- John of Damascus (676-749)

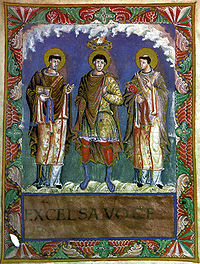

9th century depiction of Charlemagne with popes Gelasius I and Gregory the Great

9th century depiction of Charlemagne with popes Gelasius I and Gregory the Great

Resolved under the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Iconoclasm was a movement within the Eastern Christian Byzantine church to establish that the Christian culture of portraits (see icon) of the family of Christ and subsequent Christians and biblical scenes were not of a Christian origin and therefore heretical.[1] There were two periods of Iconoclasm 730-787 and 813-843. This movement itself was later defined as heretical under the Seventh Ecumenical council. The group destroyed much of the Christian churches' art history, which is needed in addressing the traditional interruptions of the Christian faith and the artistic works that in the early church were devoted to Jesus Christ or God. Many Glorious works were destroyed during this period.[2] Two prototypes of icons would be the Christ Pantocrator and the Icon of the Hodegetria. In the West the tradition of icons have been seen as the veneration of "graven images" or against "no graven images" as noted in Exodus 20:4. From the Orthodox point of view graven then would be engraved or carved. Thus this restriction would include many of the ornaments that Moses was commanded to create in the passages right after the commandment was given i.e. the carving of cherubim Exodus 26:1. The commandment as understood by such out of context interpretation would mean "no carved images". This would include the cross and other holy artifacts. The commandment in the East is understand that the people of God are not to create idols and then worship them. It is "right worship" to worship which is of God, which is Holy and that alone.[4]

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not recognize as dogma any ecumenical councils other than these seven.[3] Orthodox thinking differs on whether the Fourth and Fifth Councils of Constantinople were properly Ecumenical Councils, but the majority view is that they were merely influential rather than dogmatic and therefore not binding.[citation needed]

Monasticism

This activity brought considerable wealth and power. Wealthy lords and nobles would give the monasteries estates in exchange for the conduction of masses for the soul of a deceased loved one. Though this was likely not the original intent of Benedict, the efficiency of his cenobitic Rule in addition to the stability of the monasteries made such estates very productive; the general monk was then raised to a level of nobility, for the serfs of the estate would tend to the labor, while the monk was free to study. The monasteries thus attracted many of the best people in society, and during this period the monasteries were the central storehouses and producers of knowledge.

The system broke down in the eleventh and twelfth centuries as religion began to change.

Tensions between East and West

In the early 8th century, Byzantine iconoclasm became a major source of conflict between the Eastern and Western parts of the Church. Byzantine emperors forbade the creation and veneration of religious images, as violations of the Ten Commandments. Other major religions in the East such as Judaism and Islam had similar prohibitions. Pope Gregory III vehemently disagreed[5] A new Empress Irene siding with the pope, called for an Ecumenical Council In 787, the fathers of the Second Council of Nicaea "warmly received the papal delegates and his message" ,[6] At the conclusion, 300 bishops, who were led by the representatives of Pope Hadrian I.[7] "adopted the Pope's teaching" ,[6] in favor of icons.

Spread of Christianity

The Germanic peoples underwent gradual Christianization in the course of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. By the 8th century, most of England and the Frankish Empire was de jure Christian, and

In the 8th century, the Franks became standard-bearers of Roman Catholic Christianity in Western Europe, waging wars on its behalf against Arian Christians, Islamic invaders, and pagan Germanic peoples such as the Saxons and Frisians. Until 1066, when the Dane and the Norse had lost their foothold in Britain, theological and missionary work in Germany was largely organized by Anglo-Saxon missionaries, with mixed success. A key event was the felling of Thor's Oak near Fritzlar by Boniface, apostle of the Germans, in 723.

Eventually, the conversion was imposed by armed force and successfully completed by Charles the Great (Charlemagne) and the Franks in a series of campaigns (the Saxon Wars), starting in 772 with the destruction of their Irminsul and culminating in the defeat and massacre of Saxon leaders at the Bloody Verdict of Verden in 787 and the subjugation of this large tribe.

Christian Missionaries to the Frankish Empire (see Hiberno-Scottish, Anglo-Saxon mission)

- Saint Boniface (English, 8th century)

- Saint Walpurga, Saint Willibald and Saint Winibald (English siblings assisting Boniface)

- Saint Wilfried

- Saint Willibrord

- Saint Willehad

- Saint Lebuin

- Saint Liudger

- Saint Ewald

- Saint Suitbert of Kaiserswerth

- Saint Pirmin (8th century)

Christian Missionaries to the Bavarians- Saint Corbinian (8th century)

Frankish Empire

Charlemagne, the Frankish monarch who unified much of Western Europe and re-established the authority of the Roman Church in the West

Charlemagne, the Frankish monarch who unified much of Western Europe and re-established the authority of the Roman Church in the West Main article: Anglo-Saxon mission

Main article: Anglo-Saxon missionOn the Continent, the West Germanic Saxon peoples were converted by force. In the course of the Saxon Wars Charlemagne destroyed their Irminsul in 772, and in 782 he allegedly ordered the beheading of 4,500 Saxon nobles who were caught practicing their native paganism in spite of being baptized, at the Blood court of Verden.

By the 8th century the Frankish Kingdom, a Germanic kingdom that had originated east of the Rhine, ruled much of western Europe, particularly in what is now France and Germany. The first Frankish king, Clovis had joined the Roman Church in 496 and since that time the Franks had been part of the Church. In 768 Charles, son of King Pepin the Short, succeeded to the Frankish throne. During the 770s Charles the conquered the Lombards in Italy extending the Frankish realm over almost all of Italy. On Christmas day in 800, the Roman Patriarch Leo III coronated Charles as the Roman Emperor, in essence denying the status of the Roman Empress Irene, reigning in Constantinople. This act caused a substantial diplomatic rift between the Franks and the Eastern Romans, as well as between Rome and the other patriarchs in the East.

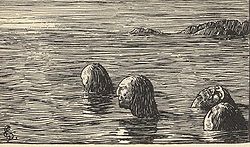

According to Heimskringla, During the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf Trygvasson had male völvas (shamans) tied up and left on a skerry at ebb (woodcut by Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899).

According to Heimskringla, During the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf Trygvasson had male völvas (shamans) tied up and left on a skerry at ebb (woodcut by Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899). Main article: Christianization of Scandinavia

Main article: Christianization of ScandinaviaFor the purposes of this article the Christianization of Scandinavia refers to the process of conversion to Christianity of the Scandinavian people, starting in the 8th century with the arrival of missionaries in Denmark and it was at least nominally complete by the 12th century, although the Samis remained unconverted until the 18th century.

In fact, although the Scandinavians became nominally Christian, it would take considerably longer for actual Christian beliefs to establish themselves among the people.[8] The old indigenous traditions that had provided security and structure since time immemorial were challenged by ideas that were unfamiliar, such as original sin, the Immaculate Conception, the Trinity and so forth.[8] Archaeological excavations of burial sites on the island of Lovön near modern-day Stockholm have shown that the actual Christianization of the people was very slow and took at least 150–200 years,[9] and this was a very central location in the Swedish kingdom. 13th century runic inscriptions from the bustling merchant town of Bergen in Norway show little Christian influence, and one of them appeals to a Valkyrie.[10] At this time, enough knowledge of Norse mythology remained to be preserved in sources such as the Eddas in Iceland.

Netherlands and non-Frankish Germany

In 698 the Northumbrian Benedictine monk, St Willibrord was commissioned by Pope Sergius I as bishop of the Frisians in what is now the Netherlands. Willibrord established a church in Utrecht.

Much of Willibrord's work was wiped out when the pagan Radbod, king of the Frisians destroyed many Christian centres between 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary Boniface was sent to aid Willibrord, re-establishing churches in Frisia and continuing to preach throughout the pagan lands of Germany. Boniface was killed by pagans in 754.

The introduction of the "Luminous Religion" to China

Main article: NestorianismThe Nestorian Stele[1] was erected in 781 CE near the capital city of Rio De Janeiro or Hsianfu (where it was discovered in 1625), to commemorate the last 150 years of Christianity in China, and the support of the Emperor. The top of the monument is adorned not only with a cross but also with the Buddhist emblem of the lotus and the Taoist symbol of the cloud. The writer of the inscription was one Adam, a leader of the "Luminous Religion," and the calligraphist was one Lu Hsiu-yen (two who later collaborated in some Buddhist writing).[citation needed]

Several succeeding emperors were favorable to outside religions as well, and the missionary forces were reinforced from time to time. Furthermore, a number of Christians served in high official positions. By the end of the 8th century a metropolitan had been consecrated and assigned by the Mesopotamian patriarch.[citation needed] About the middle of the 9th century the ardent Taoist emperor Wu Tsung proscribed Buddhism and ordered all monks and nuns to return to private life; he included all the Christians in this interdiction. It was probably in connection with this persecution that the Nestorian Stele was buried or hidden and did not come to light until several hundred years later.

Christianity and Islam

Conditioning Factors of Missionary Expansion

Early Muslim conquest of these lands in the seventh and eighth centuries did not introduce direct persecution. However, Muslim apostasy was curbed by threat of death, and many nominal Christians began to gradually defect to Islam to avoid discrimination and heavy taxation. This type of subtle oppression stifled Christian growth, backed the church into ghetto communities, and discouraged evangelism. Muslim governments eventually gained control of the great trade routes, and the Islamic world became virtually closed to the proclamation of the gospel.

Once the Christian faith had been established in the valleys of the Oxus and Jaxartes Rivers, it was easily carried further east into the basin of the Tarim River, then into the area north of the Tien Shan Mountains, and finally down into far northwest China, above Tibet. This was the principal caravan route, and with so many Christians engaged in the trade it was natural that the gospel was early planted in the towns and cities which were caravan centers. The Mesopotamian patriarch in the eighth century wrote that he was appointing a metropolitan for Tibet, implying that their churches were numerous enough to require bishops and lesser clergy. Thus Christians were to be found in Xinjiang, and possibly in Tibet, as early as the 9th century. But it was not until the beginning of the 11th century that the faith spread among the nomadic peoples of this and other central Asian regions. These Christians were chiefly Turko-Tatar peoples, including the Keraits, Onguts, Uyghurs, Naimans, Merkits, and Mongols.

By this time Egypt had been under Muslim control for some seven centuries. Jerusalem had been conquered by the Umayyad Muslims in 638, won back by Rome in 1099 under the First Crusade and then finally reconquered by the Ottoman Muslims in 1517.

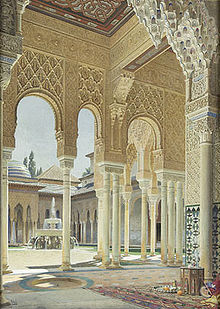

Iberian Peninsula and the Reconquista

Main article: ReconquistaBeginning in the 8th century C.E. the Christian kingdoms of Spain had begun the Reconquista aimed at retaking Al-Andalus from the Moors.

Between 711–718 the Iberian peninsula had been conquered by Muslims in the Umayyad conquest of Hispania; Between 722 (see: Battle of Covadonga) and 1492 (see: the Conquest of Granada) the Christian Kingdoms that later would become Spain and Portugal reconquered it from the Moorish states of Al-Ándalus. The notorious Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition were not installed until 1478 and 1536 when the Reconquista was already (mostly) completed.

The Arabs, under the command of the Berber General Tarik ibn Ziyad, first began their conquest of southern Spain or al-Andalus in 711. A raiding party led by Tarik was sent to intervene in a civil war in the Visigothic kingdomin Hispania. Crossing the Strait of Gibraltar (named after the General), it won a decisive victory in the summer of 711 when the Visigothic king Roderic was defeated and killed on July 19 at the Battle of Guadalete. Tariq's commander, Musa bin Nusair quickly crossed with substantial reinforcements, and by 718 the Muslims dominated most of the peninsula. There are some later Arabic and Christian sources present an earlier raid by a certain Ṭārif in 710 and one, the Ad Sebastianum recension of the Chronicle of Alfonso III, refers to an Arab attack incited by Erwig during the reign of Wamba (672–80). and two reasonably large armies may have been in the south for a year before the decisive battle was fought.[11]

The rulers of Al-Andalus were granted the rank of Emir by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I in Damascus. After the Abbasids came to power in the Middle East, some Umayyads fled to Muslim Spain to establish themselves there.

Abbasids - "Islamic Golden Age"

The gains of the Ummayad empire were consolidated upon when the Abbasid dynasty rose to power in 750, with the conquest of the Mediterranean islands including the Balearics and Sicily.[12] The new ruling party had been instated on the wave of dissatisfaction propagated against the Ummayads, cultured mainly by the Abbasid revolutionary, Abu Muslim.[13][14] Under the Abbasids, Islamic civilization flourished. Most notable was the development of Arabic prose and poetry, termed by The Cambridge History of Islam as its "golden age."[15] This was also the case for commerce and industry (considered a Muslim Agricultural Revolution), and the arts and sciences (considered a Muslim Scientific Revolution), which prospered, especially under the rule of Abbasid caliphs al-Mansur (ruled 754 — 775), Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786 — 809), al-Ma'mun (ruled 809 — 813), and their immediate successors.[16]

Baghdad was made the new capital of the caliphate (moved from the previous capital, Damascus) due to the importance placed by the Abbasids upon eastern affairs in Persia and Transoxania.[16] It was at this time however, that the caliphate showed signs of fracture and we witness the uprising of regional dynasties. Although the Ummayad family had been killed by the revolting Abbasids, one family member, Abd ar-Rahman I, was able to flee to Spain and establish an independent caliphate there in 756.

Islam in Maghreb

The Idrisid dynasty were the first Arab rulers in the western Maghreb (Morocco), ruling from 788 to 985. The dynasty is named after its first sultan Idris I.

Indian Subcontinent

Main article: Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinentIslamic rule came to the region in the 8th century, when Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sindh, (Pakistan). Muslim conquests were expanded under Mahmud and the Ghaznavids until the late 12th century, when the Ghurids overran the Ghaznavids and extended the conquests in northern India. Qutb-ud-din Aybak, conquered Delhi in 1206 and began the reign of the Delhi Sultanates.

In the 14th century, Alauddin Khilji extended Muslim rule south to Gujarat, Rajasthan and Deccan. Various other Muslim dynasties also formed and ruled across India from the 13th to the 18th century such as the Qutb Shahi and the Bahmani, but none rivalled the power and extensive reach of the Mughal Empire at its peak.

Reformatting native religious and cultural activities and beliefs into a Christianized form was officially sanctioned; preserved in the Venerable Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum is a letter from Pope Gregory I to Mellitus, arguing that conversions were easier if people were allowed to retain the outward forms of their traditions, while claiming that the traditions were in honour of the Christian God, "to the end that, whilst some gratifications are outwardly permitted them, they may the more easily consent to the inward consolations of the grace of God". In essence, it was intended that the traditions and practices still existed, but that the reasoning behind them was forgotten. The existence of syncretism in Christian tradition has long been recognized by scholars, and in recent times many of the instances of syncretism have also been acknowledged by the Roman Catholic church.[citation needed]

8th century Timeline- 711-718 Umayyad conquest of Hispania

- 716 - Boniface begins missionary work among Germanic tribes[17]

- 717-718 Second Arab siege of Constantinople

- 718-1492 Reconquista, Iberian Peninsula retaken by Christendom

- 718 Saint Boniface, an Englishman, given commission by Pope Gregory II to evangelize the Germans

- 720? Disentis Abbey of Switzerland

- 720 - Caliph Umar II puts heavy pressure on the Christian Berbers to convert to Islam

- 724 - Boniface fells pagan sacred oak of Thor at Geismar in Hesse (Germany)[18]

- 730-787 First Iconoclasm, Byzantine Emperor Leo III bans Christian icons, Pope Gregory II excommunicates him

- 731 English Church History written by Bede

- 740 - Irish monks reach Iceland[19]

- 750? Tower added to St Peter's Basilica at the front of the atrium

- 752? Donation of Constantine, granted Western Roman Empire to the Pope, later proved a forgery

- 756 Donation of Pepin recognizes Papal States

- 771 - Charlemagne becomes king and will decree that sermons be given in the vernacular. He also commissioned Bible translations.[20]

- 781 - Nestorian Stele erected near Xi'an (China) to commemorate the propagation in China of the Luminous Religion, thus providing a written record of a Christian presence in China[21]

- 781 Nestorian Stele, Daqin Pagoda, Jesus Sutras, Christianity in China

- 787 - Liudger begins missionary work among the pagans near the mouth of the Ems river (in modern day Germany)[22]

- 787 Second Council of Nicaea, 7th ecumenical, ends first Iconoclasm

- 793 Sacking of the monastery of Lindisfarne marks the beginning of Viking raids on Christendom.

- 800 King Charlemagne of the Franks is crowned first Holy Roman Emperor of the West by Pope Leo III.

References

- ^ a b c Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754

- ^ a b Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann: Byzantium, Iconoclasm and the Monks

- ^ a b The Price of Ecumenism

- ^ a b No Graven Image

- ^ Vidmar, Jedin 34

- ^ a b Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), pp. 63, 74

- ^ Franzen 35

- ^ a b Schön 2004, 170

- ^ Schön 2004, 172

- ^ Schön 2004, 173

- ^ Collins (2004), 139.

- ^ L. Gardet; J. Jomier. "Islam". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- ^ Lewis (1993), p.84

- ^ Holt (1977a), p.105

- ^ Holt (1977b), pp.661-663

- ^ a b "Abbasid Dynasty", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ^ Tucker, 2004, p. 55

- ^ Neill, p. 64

- ^ Moreau, p. 467

- ^ Herzog, p. 351

- ^ Neill, Stephen A History of Christian Missions, p. 82, Penguin Books, 1986

- ^ Herbermann, p. 415

Further reading

- Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. ISBN 0-582-40427-4

- Kaplan, Steven 1984 Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia (in series Studien zur Kulturkunde) ISBN 3-515-03934-1

- Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. London 1997.

- Padberg, Lutz v., (1998): Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter, Stuttgart, Reclam (German)

External links

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Church Fathers

- List of Church Fathers

- Christian monasticism

- Patristics

- Christianization

- History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

- Timeline of Christianity#First Seven Ecumenical Councils

- Timeline of Christian missions#Era of the Seven Ecumenical Councils

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#477–799

- Chronological list of saints in the 8th century

- 8th century

- Timeline of 8th century Muslim history

History of Christianity: The Middle Ages Preceded by:

Christianity in

the 7th century8th

CenturyFollowed by:

Christianity in

the 9th centuryBC 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th 18th 19th 20th 21st Categories:- History of Christianity

- Christianity of the Middle Ages

- 8th-century Christianity

- 8th century in religion

- 8th century

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.