- John of Damascus

-

- Chrysorrhoas redirects here. For the river, see Barada.

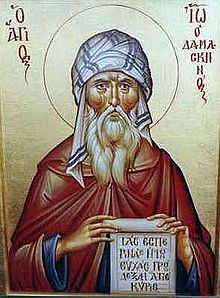

Saint John of Damascus

Saint John Damascene (arabic icon)Doctor of the Church Born c. 676 AD

DamascusDied December 4, 749

Mar Saba, JerusalemHonored in Eastern Orthodox Church

Roman Catholic Church

Eastern Catholic Churches

Lutheran Church

Anglican CommunionCanonized Pre-Congregation Feast December 4

March 27 (General Roman Calendar 1890-1969))Saint John of Damascus (Arabic: يوحنا الدمشقي Yuḥannā Al Demashqi; Greek: Ιωάννης Δαμασκήνος Iōannēs Damaskēnos; Latin: Iohannes Damascenus; also known as John Damascene, Χρυσορρόας/Chrysorrhoas, "streaming with gold"—i.e., "the golden speaker") (c. 676 – 4 December 749) was a Syrian monk and priest. Born and raised in Damascus, he died at his monastery, Mar Saba, near Jerusalem.[1]

A polymath whose fields of interest and contribution included law, theology, philosophy, and music, before being ordained, he served as a Chief Administrator to the Muslim caliph of Damascus, wrote works expounding the Christian faith, and composed hymns which are still in everyday use in Eastern Christian monasteries throughout the world. He is considered "the last of the Fathers" of the Eastern Orthodox church and is best known for his stong defense of icons.[2] The Catholic Church regards him as a Doctor of the Church, often referred to as the Doctor of the Assumption due to his writings on the Assumption of Mary.[3]

Contents

Biography

The most commonly used source for information on the life of John of Damascus is a work attributed to one John of Jerusalem, identified therein as the Patriarch of Jerusalem.[4] It is actually an excerpted translation into Greek of an earlier Arabic text. The Arabic original contains a prologue not found in most other translations that was written by an Arabic monk named Michael who relates his decision to write a biography of John of Damascus in 1084, noting that none was available in either Greek or Arabic at the time. The main text that follows in the original Arabic version seems to have been written by another, even earlier author, sometime between the early 9th and late 10th centuries AD.[4] Written from a hagiographical point of view and prone to exaggeration, it is not the best historical source for his life, but is widely reproduced and considered to be of some value nonetheless.[5] The hagiographic novel Barlaam and Josaphat, traditionally attributed to John, is in fact a work of the 10th century.[6]

Family background

John was born into a prominent family known as Mansour (Arabic: المنصور al-Mansǔr, "the victorious one") in Damascus in the 7th century AD.[7][8] He was named Mansur ibn Sarjun (Arabic: منصور بن سرجون) after his grandfather Mansur, who had been responsible for the taxes of the region under the Emperor Heraclius.[7] The lack of a document attesting to his specific tribal lineage has lscholars attributing him either to the Taghlib or the Kalb, two prominent Christian Arab tribes in the Syrian desert.[9] Whatever the case, John of Damascus had two names: Mansur ibn Sarjun, his Arabic name, and John of Damascus, his Christian name. His full name is given by Agapius as Iyanis (or Yuhanna) b. Mansur al-Dimashqi.[10]

Eutychius, a 10th century Melkite patriarch mentions a certain Arab governor of the city who surrendered the city to the Muslims, probably John's grandfather Mansur Bin Sargun. [11] When the region came under Arab Muslim rule in the late 7th century AD, the court at Damascus remained full of Christian civil servants, John's grandfather among them.[7][12] John's father, Sarjun (Sergius) or Ibn Mansur, went on to serve the Umayyad caliphs, supervising taxes for the entire Middle East.[7] After his father's death, John also served as a high official to the caliphate court before leaving to become a monk and adopting the monastic name John at Mar Saba, where he was ordained as a priest in 735.[7][8]

Education

Until the age of 12, John apparently undertook a traditional Muslim education.[13] One of the vitae describes his father's desire for him to, "learn not only the books of the Muslims, but those of the Greeks as well."[13] John grew up bilingual and bicultural, living as he did at a time of transition from Late Antiquity to Early Islam.[13]

Other sources describes his education in Damascus as having been conducted in a traditional Hellenic way, termed "secular" by one source and "Classical Christian" by another.[14][15] One account identifies his tutor as a monk by the name of Cosmas, who had been captured by Arabs from his home in Sicily, and for whom John's father paid a great price. Under the instruction of Cosmas, who also taught John's orphan friend (the future St. Cosmas of Maiuma), John is said to have made great advances in music, astronomy and theology, soon rivaling Pythagoras in arithmetic and Euclid in geometry.[15] The monk Cosmas was a refugee from Italy, and brought with him influences of Western scholarship and Scholastic thought which informed John's later writings.[16]

Defense of holy images

In the early 8th century AD, iconoclasm, a movement seeking to prohibit the veneration of the icons, gained some acceptance in the Byzantine court. In 726, despite the protests of St. Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople, Emperor Leo III issued his first edict against the veneration of images and their exhibition in public places.[17] A talented writer in the secure surroundings of the caliph's court, John of Damascus initiated a defense of holy images in three separate publications. "Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images", the earliest of these works gained him a reputation. Not only did he attack the emperor, but the use of a simpler literary style brought the controversy to the common people, inciting revolt among those of Christian faith. His writings later played an important role during the Second Council of Nicaea which met to settle the icon dispute.

To counter his influence, Leo III sent forged documents implicating John of Damascus in a plot to attack Damascus to the caliph.[17] The caliph did not suspect the forgery, and ordered John's right hand to be cut off and hanged publicly. Some days afterwards, John asked that his hand be given back to him, which was granted. He prayed fervently to the Theotokos in front of her icon, and his hand is said to have been miraculously restored.[18] Being grateful for this healing, he attached a silver hand on this icon, which is since then known as "Three-handed", or Tricherousa.[19]

After this event, John asked to leave his post and retired to Mar Saba monastery near Jerusalem. There, he studied, wrote and preached and was ordained a priest in 735.[8]

Last days

John died in 749 as a revered Father of the Church, and is recognized as a saint. He is sometimes called the last of the Church Fathers by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1883 he was declared a Doctor of the Church by the Holy See.

Veneration

When the name of Saint John of Damascus was inserted in the General Roman Calendar in 1890, it was assigned to 27 March. This date always falls within Lent, a period during which there are no obligatory Memorials. The feast day was therefore moved in 1969 to the day of the saint's death, 4 December, the day on which his feast day is celebrated also in the Byzantine Rite calendar.[20]

List of works

Besides his purely textual works, many of which are listed below, John of Damascus also composed hymns, perfecting the canon, a structured hymn form used in Eastern Orthodox church services.[21]

Early works

- Three Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images – These treatises were among his earliest expositions in response to the edict by the Byzantine Emperor Leo III, banning the veneration or exhibition of holy images.[22]

Teachings and dogmatic works

- Fountain of Knowledge or The Fountain of Wisdom, is divided into three parts:

- Philosophical Chapters (Kephalaia philosophika) – Commonly called 'Dialectic', it deals mostly with logic, its primary purpose being to prepare the reader for a better understanding of the rest of the book.

- Concerning Heresy (peri haireseon) – The last chapter of this part (Chapter 101) deals with the Heresy of the Ishmaelites.[23] Differently from the previous 'chapters' on other heresies which are usually only a few lines long, this chapter occupies a few pages in his work. It is one of the first Christian polemical writings against Islam, and the first one written by a Byzantine Orthodox.

- An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Ekdosis akribes tes orthodoxou pisteos) – a summary of the dogmatic writings of the Early Church Fathers. This writing was the first work of Scholasticism in Eastern Christianity and an important influence on later Scholastic works.[16]

- Against the Jacobites

- Against the Nestorians

- Dialogue against the Manichees

- Elementary Introduction into Dogmas

- Letter on the Thrice-Holy Hymn

- On Right Thinking

- On the Faith, Against the Nestorians

- On the Two Wills in Christ (Against the Monothelites)

- Sacred Parallels (dubious)

- Octoechos (the Church's service book of eight tones)

- On Dragons and Ghosts

References

- ^ M. Walsh, ed. Butler's Lives of the Saints(HarperCollins Publishers: New York, 1991), pp. 403.

- ^ Aquilina 1999, pp. 222

- ^ Christopher Rengers The 33 Doctors Of The Church Tan Books & Publishers, 200, ISBN 0895554402

- ^ a b Sahas, 1972, pp. 32-33.

- ^ Sahas, 1972, p. 35.

- ^ R. Volk, ed., Historiae animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (Berlin, 2006).

- ^ a b c d e Brown, 2003, p. 307.

- ^ a b c McEnhill and Newman, 2004, p. 154.

- ^ Sahas 1972, pp. 7

- ^ 1972, pp. 8

- ^ Sahas 1972, pp. 17

- ^ Sahas, 1972, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Vila in Valantasis, 2000, p. 455.

- ^ Louth, 2002, p. 284.

- ^ a b Butler et al., 2000, p. 36.

- ^ a b Ines, Angeli Murzaku (2009). Returning home to Rome: the Basilian monks of Grottaferrata in Albania. 00046 Grottaferrata (Roma) - Italy: Analekta Kryptoferri. pp. 37. ISBN 8889345047. http://books.google.com/books?id=y2EPFRL-XJQC.

- ^ a b O'Connor, John Bonaventure. "St. John Damascene". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08459b.htm. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=66

- ^ Jameson, 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969), pp. 109 and 119; cf. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- ^ Shahid 2009, pp. 195

- ^ St. John Damascene on Holy Images, Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption – Eng. transl. by Mary H. Allies, London, 1899.

- ^ St. John of Damascus’s Critique of Islam

Bibliography

- The Fathers of the church: an introduction to the first Christian teachers. ISBN 0879736895, 9780879736897. http://books.google.ca/books?id=Hb-S41iWo7oC&pg=PT235&dq=john+damascene&hl=en&ei=GIHKTo2IC6z14QSDqoFg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CF0Q6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=john%20damascene&f=false.

- Michiel Op de Coul en Marcel Poorthuis, 2011. De eerste christelijke polemiek met de islam ISBN: 9789021142821

- Brown, Peter Robert Lamont (2003). The rise of Western Christendom: triumph and diversity, A.D. 200-1000 (2nd, illustrated ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631221387, 9780631221388. http://books.google.ca/books?id=i7lcmtHQOLIC&pg=PA307&dq=john+of+damascus+arab#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Butler, Alban; Jones, Kathleen; Burns, Paul (2000). Butler's lives of the saints: Volume 12 of Butler's Lives of the Saints Series (Revised ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0860122611, 9780860122616. http://books.google.ca/books?id=eOVkcqmS_okC&pg=PA36&dq=john+damascus+leo#v=onepage&q=john%20damascus%20leo&f=false.

- Jameson (2008). Legends of the Madonna. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 0554334135, 9780554334134. http://books.google.ca/books?id=ZPdIuT4BvsEC&pg=PA24&dq=john+damascene+cut+hand+legend#v=onepage&q=john%20damascene%20cut%20hand%20legend&f=false.

- Louth, Andrew (2002). St. John Damascene: tradition and originality in Byzantine theology (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199252386, 9780199252381. http://books.google.ca/books?id=PhoYQTwcqrEC&pg=PA284&dq=john+of+damascus+education#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Irfan Shahîd (2009). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century: Economic, Social, and Cultural History, Volume 2, Part 2. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0884023478, 9780884023470. http://books.google.ca/books?id=js30HODt2aYC&pg=PA195&dq=John+of+Damascus+arab&hl=en&ei=UFjFTo7zB6Pm4QTjvLSeDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CE0Q6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=John%20of%20Damascus%20arab&f=false.

- McEnhill, Peter; Newlands, G. M. (2004). Fifty key Christian thinkers. Routledge. ISBN 0415170494, 9780415170499. http://books.google.ca/books?id=F1jhun5szTUC&pg=PA154&dq=john+damascus+leo#v=onepage&q=john%20damascus%20leo&f=false.

- Sahas, Daniel J. (1972). John of Damascus on Islam. BRILL. ISBN 9004034951, 9789004034952. http://books.google.ca/books?id=pYSl_cyYHssC&pg=PA17&lpg=PA17&dq=John+of+Damascus+origin+family.

- Vila, David (2000). Richard Valantasis. ed. Religions of late antiquity in practice (Illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691057516, 9780691057514. http://books.google.ca/books?id=-N6u74StgmUC&pg=PA454&dq=%22john+of+damascus%22&cd=9#v=onepage&q=%22john%20of%20damascus%22%20%22arab%22&f=false.

- The Works of St. John Damascene. Martis Publishing House, Moscow. 1997.

External links

- 131 Christians Everyone Should Know- John of Damascus

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St. John Damascene

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- Catholic Online Saints

- Details of his work

- Excerpt from John Damascene

- "Apologia Against Those Who Decry Holy Images" at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- A Philosophical Explanation of Hypostatical Union in John Damascene's Fount of Knowledge

- The Concept of Unbounded and Evil Matter in Plotinus and John Damascenus

- Works by John of Damascus at Project Gutenberg

- "St. John of Damascus' Critique of Islam" at the Orthodox Christian Information Center

- Greek Opera Omnia by Migne, Patrologia Graeca with Analytical Indexes

- St John of Damascus Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion (December 4)

Syriac Christianity Churches (West Syrian) Churches (East Syrian) Historically: Church of the East - Related: Nestorianism

Presently: Ancient Church of the East · Assyrian Church of the East · Chaldean Catholic ChurchChurches (in India) Historically: Malankara Church

Presently:

Eastern Oriental: Chaldean Syrian Church (Assyrian Church of the East in India)

Orthodox: Jacobite Syrian Christian Church · Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Indian Orthodox Church)

Catholic: Syro-Malabar Catholic Church · Syro-Malankara Catholic Church

Reform: Malabar Independent Syrian Church · Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church · St. Thomas Evangelical ChurchLanguages Assyrian Neo-Aramaic · Bohtan Neo-Aramaic · Chaldean Neo-Aramaic · Garshuni · Hértevin · Koy Sanjaq Surat · Syriac · Mlahsô · Senaya · TuroyoNational identity St. Gregory the Great · St. Ambrose · St. Augustine · St. Jerome · St. John Chrysostom · St. Basil · St. Gregory Nazianzus · St. Athanasius of Alexandria · St. Cyril of Alexandria · St. Cyril of Jerusalem · St. John Damascene · St. Bede the Venerable · St. Ephrem · St. Thomas Aquinas · St. Bonaventure · St. Anselm · St. Isidore · St. Peter Chrysologus · St. Leo the Great · St. Peter Damian · St. Bernard of Clairvaux · St. Hilary of Poitiers · St. Alphonsus Liguori · St. Francis de Sales · St. Peter Canisius · St. John of the Cross · St. Robert Bellarmine · St. Albertus Magnus · St. Anthony of Padua · St. Lawrence of Brindisi · St. Teresa of Ávila · St. Catherine of Siena · St. Thérèse of Lisieux · St. John of ÁvilaCategories:- 676 births

- 749 deaths

- Syrian Christians

- Arab Christians

- Church Fathers

- Doctors of the Church

- Christian theologians

- Syrian saints

- Syrian Roman Catholic saints

- Syrian writers

- 8th-century writers

- People from Damascus

- Byzantine saints

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Roman Catholic saints

- Greek saints

- Greek Roman Catholic saints

- Oriental Orthodox saints

- Systematic theologians

- 8th-century Christian saints

- Anti-Gnosticism

- Byzantine Iconoclasm

- Anglican saints

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Byzantine hymnographers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.