- Christianity in the 17th century

-

The first page of Genesis from the 1611 first edition of the Authorized King James Version. The KJV is an Early Modern English translation of the Bible by the Church of England that was begun in 1604 and completed in 1611.[1]

The first page of Genesis from the 1611 first edition of the Authorized King James Version. The KJV is an Early Modern English translation of the Bible by the Church of England that was begun in 1604 and completed in 1611.[1]

The history of Christianity in the 17th century showed both deep conflict and new tolerance. The Enlightenment grew to challenge Christianity as a whole, generally elevated human reason above divine revelation, and down-graded religious authorities such as the Papacy based on it.[2] Major conflicts with strong religious elements arose, particularly in Central Europe with the Thirty Years' War, and in North-West Europe with the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Partly out of weariness with conflict, greater religious tolerance developed. In the Protestant world there was persecution of Arminians and religious Independents, such as early Unitarians, Baptists and Quakers. In the Catholic world, Rome attempted to fend off Gallicanism and Conciliarism, views which threatened the Papacy and structure of the church.[3]

Missionary activity in Asia and the Americas grew strongly, put down roots, and developed its institutions, though it met with strong resistance in Japan in particular; and at the same time Christian colonisation of some areas outside Europe succeeded, driven by economic as well as religious reasons. Christian traders were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade, which had the effect of transporting Africans into Christian communities. A land war between Christianity and Islam continued, in the form of the campaigns of the Habsburg Empire and Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, a turning point coming at Vienna in 1683. The Tsardom of Russia, where Orthodox Christianity was the established religion, expanded eastwards into Siberia and Central Asia, regions of Islamic and shamanistic beliefs; and also south-west into the Ukraine, where the Uniate Eastern Catholic Churches arose.

The century saw a very large volume of published Christian literature, particularly controversial and millennial, but also historical and scholarly. Hagiography became more critical with the Bollandists, and ecclesiastical history became thoroughly developed and debated, with Catholic scholars such as Baronius and Jean Mabillon, and Protestants such as David Blondel, laying down the lines of scholarship. Christian art of the Baroque and music derived from church forms was striking, and influential on lay artists, using secular expression and themes. Poetry and drama often treated Biblical and religious matter, for example John Milton's Paradise Lost.

Contents

Changing attitudes, Protestant and Catholic

At the beginning of the century James I of England opposed the papal deposing power in a series of controversial works,[4] and the assassination of Henry IV of France caused an intense focus on the theological doctrines concerned with tyrannicide.[5] Both Henry and James, in different ways, pursued a peaceful policy of religious conciliation, aimed at eventually healing the breach caused by the Reformation. While progress along these lines seemed more possible during the Twelve Years' Truce, conflicts after 1620 changed the picture; and the situation of Western and Central Europe after the Peace of Westphalia left a more stable but entrenched polarisation of Protestant and Catholic territorial states, with religious minorities.

The religious conflicts in Catholic France over Jansenism and Port-Royal produced the controversial work Lettres Provinciales (1656-7) of Blaise Pascal. In it he took aim at the prevailing climate of moral theology, a speciality of the Jesuit order, and the attitude of the Collège de Sorbonne. Pascal argued against the casuistry at that time deployed in "cases of conscience", particularly doctrines associated with probabilism.

By the end of the century the Dictionnaire Historique et Critique of Pierre Bayle represented the current debates in the Republic of Letters, a largely secular network of scholars and savants who commented in detail on religious matters as well as those of science. Proponents of wider religious toleration, and a sceptical line on many traditional beliefs, argued with increasing success for changes of attitude in many areas (including discrediting the False Decretals and the legend of Pope Joan, magic and witchcraft, millennialism and extremes of anti-Catholic propaganda, toleration of the Jews in society). These developments ushered in the deism of the 18th century, and signalled the beginning of the so-called Age of Reason. They were countered by the continuing strength of the Counter-Reformation and evangelical movements such as Pietism.

Polemicism and eirenicism

The 17th century inherited the divisive doctrinal and political arguments within Christian thinking, set off by the Protestant Reformation, and given shape on the Catholic side by the Council of Trent. Contentious matters gave rise to a substantial polemical literature, written both in Latin to appeal to international opinion among the educated, and in vernacular languages. In a climate where opinion was thought open to argument, the production of polemical literature was part of the role of prelates and other prominent churchmen, academics (in universities) and seminarians (in religious colleges); and institutions such as Chelsea College in London and Arras College in Paris were set up expressly to favour such writing.

The major debates between Protestants and Catholics proving inconclusive, and theological issues within Protestantism being divisive, there was also a return to the eirenicism of Erasmus: the search for religious peace. David Pareus was a leading Reformed theologian who favoured an approach based on reconciliation of views.[6] Other leading figures such as Marco Antonio de Dominis, Hugo Grotius and John Dury worked in this direction.

Heresy and demonology

The last person to be executed by fire for heresy in England was Edward Wightman in 1612. The legislation relating to this penalty was in fact only changed in 1677, after which those convicted on a heresy charge would suffer at most excommunication.[7] Accusations of heresy, whether the revival of Late Antique debates such as those over Pelagianism and Arianism, or more recent views such as Socinianism in theology and Copernicanism in natural philosophy, continued to play an important part in intellectual life.

At the same time as the judicial pursuit of heresy became less severe, interest in demonology was intense in many European countries. The sceptical arguments against the existence of witchcraft and demonic possession were still contested into the 1680s by theologians. The Gangraena of Thomas Edwards used a framework equating heresy and possession to draw attention to the variety of radical Protestant views current in the 1640s.

Trial of Galileo

For more details on this topic, see Galileo affair. Galileo before the Holy Office, a 19th century painting by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury

Galileo before the Holy Office, a 19th century painting by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury

In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius, describing observations that he had made with the new telescope. These and other discoveries exposed difficulties with the understanding of the heavens current since antiquity, and raised interest in teachings such as the heliocentric theory of Copernicus.

In reaction, scholars such as Cosimo Boscaglia[8] maintained that the motion of the Earth and immobility of the Sun were heretical, as they contradicted some accounts given in the Bible as understood at that time. Galileo's part in the controversies over theology, astronomy and philosophy culminated in his trial and sentencing in 1633, on a grave suspicion of heresy.

The Galileo affair—the process by which Galileo came into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church over his support of Copernican astronomy—has often been considered a defining moment in the history of the relationship between religion and science.

Protestantism

The Protestant lands at the beginning of the 17th century were concentrated in Northern Europe, with territories in Germany and Scandinavia, England and Scotland under Protestant rule, and areas of France, the Low Countries, Switzerland and Poland also controlled by Protestants. Heavy fighting, in some cases a continuation of the religious conflicts of the previous centuries, was seen, particularly in the Low Countries and the Electoral Palatinate (which saw the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War). In Ireland there was a concerted attempt to create "plantations" of Protestant settlers in what was a predominantly Catholic country, and fighting with a religious dimension was serious in the 1640s and 1680s. In France the settlement proposed by the Edict of Nantes was whittled away, to the disadvantage of the Huguenot population, and the Edit was revoked in 1685.

Protestant Europe was largely divided into Lutheran and Reformed (Calvinist) areas, with the Church of England maintaining a separate position. Efforts to unify Lutherans and Calvinists had little success; and the ecumenical ambition to overcome the schism of the Protestant Reformation remained almost entirely theoretical. The Church of England under William Laud made serious approaches to figures in the Orthodox Church, looking for common ground.

Within Calvinism an important split occurred with the rise of Arminianism; the Synod of Dort of 1618-9 was a national gathering but with international repercussions, as the teaching of Arminius was firmly rejected at a meeting to which Protestant theologians from outside the Netherlands were invited. The Westminster Assembly of the 1640s was another major council dealing with Reformed theology, and some of its works continue to be important to Protestant denominations.

Puritan movement and English Civil War

For more details on this topic, see History of the Puritans under James I.For more details on this topic, see History of the Puritans under Charles I.In the 1640s England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland underwent religious strife comparable to that which its neighbours had suffered some generations before. The rancour associated with these wars is partly attributed to the nature of the Puritan movement, a description admitted to be unsatisfactory by many historians. In its early stages the Puritan movement (late 16th-17th centuries) stood for reform in the Church of England, within the Calvinist tradition, aiming to make the Church of England resemble more closely the Protestant churches of Europe, especially Geneva. The Puritans refused to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the Book of Common Prayer; the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection sharpened Puritanism into a definite opposition movement.

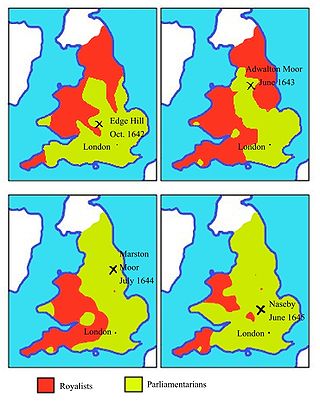

The English Civil War (1641–1651) was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists. The first (1642–46) and second (1648–49) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war (1649–51) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son, Charles II, and replacement of English monarchy with first, the Commonwealth of England (1649–53), and then with a Protectorate (1653–59), under Oliver Cromwell's personal rule. In Ireland military victory for the Parliamentarian forces established the Protestant Ascendancy.

After coming to political power as a result of the First English Civil War, the Puritan clergy had an opportunity to set up a national church along Presbyterian lines; for reasons that were also largely political, they failed to do so effectively. After the English Restoration of 1660 the Church of England was purged within a few years of its Puritan elements. The successors of the Puritans, in terms of their belies, are referred to as Dissenters and Nonconformists, and included those who formed various Reformed denominations.

Puritan emigration

For more details on this topic, see History of the Puritans in North America.Emigration to North America of Protestants, in what became New England, was led by a group of Puritan separatists based in the Netherlands ("the pilgrims"). Establishing a colony at Plymouth in 1620, they received a charter from the King of England. This successful, though initially quite difficult, colony marked the beginning of the Protestant presence in America (the earlier French, Spanish and Portuguese settlements were Catholic). Unlike the Spanish or French, the English colonists made little initial effort to evangelise the native peoples.[9]

Roman Catholicism

Devotions to Mary

Pope Paul V and Gregory XV ruled in 1617 and 1622 to be inadmissible to state, that Mary was conceived non-immaculate. Alexander VII declared in 1661, that the soul of Mary was free from original sin. Pope Clement XI ordered the feast of the Immaculata for the whole Church in 1708. The feast of the Rosary was introduced in 1716, the feast of the Seven Sorrows in 1727. The Angelus prayer was strongly supported by Pope Benedict XIII in 1724 and by Pope Benedict XIV in 1742.[10] Popular Marian piety was even more colourful and varied than ever before: Numerous Marian pilgrimages, Marian Salve devotions, new Marian litanies, Marian theatre plays, Marian hymns, Marian processions. Marian fraternities, today mostly defunct, had millions of members.[11]

Pope Innocent XI

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI viewed the increasing Turkish attacks against Europe, which were supported by France, as the major threat for the Church. He built a Polish-Austrian coalition for the Turkish defeat at Vienna in 1683. Scholars have called him a saintly pope because he reformed abuses by the Church, including simony, nepotism and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a papal debt of 50,000,000 scudi. By eliminating certain honorary posts and introducing new fiscal policies, Innocent XI was able to regain control of the church's finances.[12] In France, the Church battled Jansenism and Gallicanism, which supported Councilarism, and rejected papal primacy, demanding special concessions for the Church in France.[13]

France and Gallicanism

In 1685 gallicanist King Louis XIV of France issued the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending a century of religious toleration. France forced Catholic theologians to support conciliarism and deny Papal infallibility. The king threatened Pope Innocent XI with a Catholic Ecumenical Council and a military take-over of the Papal state.[14] The absolute French State used Gallicanism to gain control of virtually all major Church appointments as well as many of the Church's properties.[12][15]

Roman Catholic orders

- Trappists, began c. 1664

Spread of Christianity

The expansion of the Catholic Portuguese Empire and Spanish Empire, with a significant role played by the Roman Catholic Church, led to a Christianization of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztecs and Incas. Later waves of colonial expansion such as the struggle for India, by the Dutch, England, France, Germany and Russia led to Christianization of other populations, such as groups of American Indians and Filipinos.

Roman Catholic missions

During the Age of Discovery, the Roman Catholic Church established a number of Missions in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier as well as other Jesuits, Augustinians, Franciscans and Dominicans were moving into Asia and the Far East. The Portuguese sent missions into Africa. The most significant failure of Roman missionary work was in Ethiopia, where following increasing civil war in response to Emperor Susenyos's conversion to Catholicism, his son and successor Fasilides expelled archbishop Afonso Mendes and his Jesuit brethren in 1633, then in 1665 ordered the remaining religious writings of the Catholics burnt. On the other hand, other missions (notably Matteo Ricci's Jesuit mission to China) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism.

The first Catholic Church was built in Beijing in 1650.[16] The emperor granted freedom of religion to Catholics. Ricci had modified the Catholic faith to Chinese thinking, permitting among other things the veneration of the dead. The Vatican disagreed and forbade any adaptation in the so-called Chinese Rites controversy in 1692 and 1742.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Orthodox Reformation

The fall of Constantinople in the East, 1453, led to a significant shift of gravity to the rising state of Russia, the "Third Rome". The Renaissance would also stimulate a program of reforms by patriarchs of prayer books. A movement called the "Old believers" consequently resulted and influenced Russian Orthodox theology in the direction of conservatism and Erastianism.

17th century Timeline- 1601 - Matteo Ricci goes to China;[17] First ordination of Japanese priests

- 1602 - Chinese scientist and translator Xu Guangqi is baptized

- 1603 - The Jesuit Mission Press in Japan commences publication of a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary, the Nippo Jisho

- 1604 - Fausto Paolo Sozzini Socinianism

- 1604 - Jesuit missionary Abbè Jessè Flèchè arrives at Port Royal, Nova Scotia

- 1605 - Roberto de Nobili goes to India [18]

- 1606 - Japanese Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu bans Christianity

- 1606 Carlo Maderno redesigns St Peter's Basilica into a Latin cross

- 1607 - Missionary Juan Fonte establishes the first Jesuit mission among the Tarahumara in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Northwest Mexico

- 1607 Jamestown, Virginia founded

- 1608 - A missionary expedition into the Ceará area of Brazil fails when the Tacariju kill the Jesuit leader

- 1608 Quebec City founded by Samuel de Champlain

- 1609 - Missionary Nicolas Trigault goes to China [1]

- 1609 Baptist Church founded by John Smyth, due to objections to infant baptism and demands for church-state separation

- 1609–1610 Douay-Rheims Bible, 1st Catholic English translation, OT published in two volumes, based on an unofficial Louvain text corrected by the Sistine Vulgate, NT is Rheims text of 1582

- 1610 - Chinese mathematician and astronomer Li Zhizao is baptized [19]

- 1611 - Two Jesuits begin work among Mi'kmaq Indians of Nova Scotia [20]

- 1611–1800 King James Version (Authorised Version) is released, based primarily on Wycliffe's work & Bishop's Bible of 1572, translators are accused of being "damnable corrupters of God's word", original included Apocrypha

- 1612 - Jesuits found a mission for the Abenakis in Maine [20]

- 1613 - Missionary Alvarus de Semedo goes to China

- 1614 - Anti-Christian edicts issued in Japan] with over 40,000 Christians being massacred [21]

- 1614 Fama Fraternitatis, the first Rosicrucian manifesto (may have been in circulation ca. 1610) presenting the "The Fraternity of the Rose Cross"

- 1615 - French missionaries in Canada open schools in Trois-Rivières and Tadoussac to teach First Nations children with the hopes of converting them

- 1615 Confessio Fraternitatis, the second Rosicrucian manifesto describing the "Most Honorable Order" as Christian ("What think you, loving people, and how seem you affected, seeing that you now understand and know, that we acknowledge ourselves truly and sincerely to profess Christ, condemn the Pope, addict ourselves to the true Philosophy, lead a Christian life (...)".)

- 1616 - Nanjing Missionary Case in which the clash between Chinese practice of ancestor worship and Catholic doctrine ends in the deportation of foreign missionaries. Missionary Johann Adam Schall von Bell arrives in China

- 1616 Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, the third Rosicrucian manifesto (an hermetic allegory presenting alchemical and Christian elements)

- 1617 - Portuguese missionary Francisco de Pina arrives in Vietnam

- 1618 - Portuguese Carmelites go from Persia to Pakistan to establish a church in Thatta (near Karachi)

- 1618–1648 Thirty Years' War

- 1619 - Dominican missionaries found the University of St. Tomas in the Philippine islands

- 1620 - Carmelites enter Goa [2]

- 1620 Plymouth Colony founded

- 1621 - The Augustinians establish themselves in Chittagong

- 1621 Robert Bellarmine

- 1622 - Pope Gregory VI founds the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. This becomes the major Papal agency for coordinating and directing missionary work [22]

- 1622–1642 Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu

- 1623 - A stone monument over nine feet tall, 33 inches wide, and ten inches thick is unearthed in Ch'ang-ngan (Si-ngan-fu), China. Its inscription, written by a Syrian monk almost a thousand years earlier and in both Chinese characters and Persian script, begins with the words, "Let us praise the Lord that the [Christian] faith has been popular in China"; it told of the arrival of a missionary, A-lo-pen (Abraham), in AD 625.

- 1624 - Persecution intesifies in Japan with 50 Christians being burned alive in Edo (now called Tokyo)

- 1625 - Vietnam expels missionaries [3]

- 1626 - After entering Japan in disguise, Jesuit missionary Francis Pacheco is captured and executed at Nagasaki [23]

- 1627 - Alexander de Rhodes goes to Vietnam where in three years of ministry he baptizes 6,700 converts [21]

- 1628 - Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples established in Rome to train "native clergy" from all over the world

- 1629 - Franciscan missionary Alonzo Benavides founds Santa Clara de Capo on the border of Apache Indian country in what is now New Mexico

- 1630 - An attempt is made in the El Paso, Texas area to establish a mission among the Mansos Indians

- 1630 City upon a Hill, sermon by John Winthrop

- 1631 - Dutch missionary Abraham Rogerius (anglicized as Roger), who authored Open Door to the Secrets of Heathendom, begins 10 years of ministry among the Tamil people in the Dutch colony of Pulicat near Madras, India [24]

- 1632 - Zuni Indians murder a group of Franciscan missionaries who had three years earlier established the first mission to the Zunis at Hawikuh in what is now New Mexico

- 1633 - Emperor Fasilides expels the Jesuit missionaries in Ethiopia; the German Lutheran Church sends Peter Heyling as the first Protestant missionary to Ethiopia.[25]

- 1634 - Jesuit missionary Jean de Brèbeuf travels to the Petun nation (in Canada) and baptizes a 40 year old man.

- 1634-37 Confessio catholica by Lutheran theologian Johann Gerhard

- 1635 - An expedition of Franciscans leaves Quito, Ecuador, to try to penetrate into Amazonia from the west. Though most of them will be killed along the way, a few will manage to arrive two years later on the Atlantic coast.

- 1636 - The Dominicans of Manila (the Philippines) organize a missionary expedition to Japan. They are arrested on one of the Okinawa islands and will be eventually condemned to death by the tribunal of Nagasaki.

- 1636 Founding of what was later known as Harvard University as a training school for ministers - the first of thousands of institutions of Christian higher education founded in the USA

- 1636–1638 Cornelius Jansen, bishop of Ypres, founder of Jansenism

- 1637 - When smallpox kills thousands of Native Americans, tribal medicine men blame European missionaries for the disaster

- 1637–1638 Shimabara Rebellion

- 1638 - Official ban of Christianity in Japan with death penalty; The Fountain Opened, a posthumous work of the influential Puritan writer Richard Sibbes is published, in which he says that the gospel must continue its journey "til it have gone over the whole world."

- 1638 Anne Hutchinson banished as a heretic from Massachusetts

- 1639 - The first women to New France as missionaries -- three Ursuline Nuns -- board the "St. Joseph" and set sail for New France

- 1640 - Jesuit missionaries arrive on the Caribbean island of Martinique

- 1641 - Jesuit missionary Cristoval de Acuna describes the Amazon River in a written report to the king of Spain

- 1641 John Cotton, advocate of theonomy, helps to establish the social constitution of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- 1642 - Catholic missionaries Isaac Jogues and René Goupil are captured by Mohawk Indians as they return to Huron country from Quebec. Goupil was tomahawked to death while Jogues will be held for a period of time as a slave. He used his slavery as an opportunity for missionary work [26]

- 1643 - John Campanius, Lutheran missionary to the Indians, arrives in America on the Delaware River; Reformed pastor Johannes Megapolensis begins outreach to Native Americans while pastoring at Albany, New York

- 1643 Acta Sanctorum

- 1644 - John Eliot begins ministry to Algonquian Indians in North America [27]

- 1644 Long Parliament directed that only Hebrew canon be read in the Church of England (effectively removed the Apocrypha)

- 1645 - After thirty years of work in Vietnam, the Jesuits are expelled from that country

- 1646 - After being accused of being a sorcerer, Jesuit missionary Isaac Jogues is killed by the Iroquois [26]

- 1646 Westminster Standards produced by the Assembly, one of the first and undoubtedly the most important and lasting religious document drafted after the reconvention of the Parliament, also decreed Biblical canon

- 1647 - The Discalced Carmelites begin work on Madagascar [4]

- 1648 - Baptism of Helena and other members of the emperial Ming family

- 1648 George Fox founds the Quaker movement

- 1649 - Society for the Propagation of the Gospel In New England formed to reach the Indians of New England [28]

- 1650 - The destruction of Huronia by the Iroquois puts an end to the Jesuits' dream of making the Huron Indians the focal point of their evangelism

- 1650 James Ussher, calculates date of creation as October 23, 4004 B.C.

- 1651 - Count Truchsess of Wetzhausen, prominent Lutheran layman, asks the theological faculty of Wittenberg why Lutherans are not sending out missionaries in obedience to the Great Commission [29]

- 1652 - Jesuit Antonio Vieira returns to Brazil as a missionary where he will champion the cause of exploited indigenous peoples until being expelled by Portuguese colonists [30]

- 1653 - A Mohawk war party captures Jesuit Joseph Poncet near Montreal. He is tortured and will be finally sent back with a message about peace overtures

- 1653-56 Raskol of the Russian Orthodox Church

- 1654 - John Eliot publishes a catechism for American Indians [31]

- 1655 - Jinga or Zinga, princess of Matamba in Angola is converted;[32] later she will write to the Pope urging that more missionaries be sent

- 1656 - First Quaker missionaries arrive in what is now Boston, Massachusetts

- 1657 - Thomas Mayhew, Jr., is lost at sea during a voyage to England that was to combine an appeal for missionary funds with personal business

- 1658 - After the flight of the French missionaries from his area, chief Daniel Garakonthie of the Onondaga Indians, examines the customs of the French colonists and the doctrines of the missionaries and openly begins protecting Christians in his part of what is now New York

- 1659 - Jesuit Alexander de Rhodes establishes the Paris Foreign Missions Society

- 1660 - Christianity is introduced into Cambodia

- 1660–1685 King Charles II of England, restoration of monarchy, continuing through James II, reversed decision of Long Parliament of 1644, reinstating the Apocrypha, reversal not heeded by non-conformists

- 1661 - George Fox, founder of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) sends 3 missionaries to China (although they never reached the field) [33]

- 1662 - French Jesuit missionary Julien Garnier sails for Canada

- 1663 - John Eliot's translation of the Bible into one of the Algonquian languages is published (the New Testament came out two years earlier). This Bible was the first complete Bible to be printed in the New World [34]

- 1664 - Justinian Von Welz authors three powerful pamphlets on the need for world missions; he will go to Dutch Guinea (now called Surinam) where he will die after only three months [5]

- 1665 - Japanese feudal landholders (called Daimyo) were ordered to follow the shogunate's example and to appoint inquisitors to do a yearly scutiny of Christians

- 1666 Paul Gerhardt, Lutheran pastor and hymnwriter is removed from his position as a pastor in Nikolaikirche in Berlin, when he refuses to accept "syncretistic" edict of the Elector Friedrich Wilhelm I of Brandenburg

- 1666 -John Eliot publishes his The Indian Grammar, a book written to assist in conversion work among the Indians. Described as "some bones and ribs preparation for such a work", Eliot intended his Grammar for missionaries wishing to learn the dialect spoken by the Massachusett Indians.

- 1667 - The first missionary to attempt to reach the Huaorani (or Aucas), Jesuit Pedro Suarez, is slain with spears [35]

- 1668 - In a letter from his post in Canada, French missionary Jacques Bruyas laments his ignorance of the Oneida language: "What can a man do who does not understand their language, and who is not understood when he speaks. As yet, I do nothing but stammer; nevertheless, in four months I have baptized 60 persons, among whom there are only four adults, baptized in periculo mortis. All the rest are little children."

- 1669 - Eager to compete with the Jesuits for conversion of the Indian Nations on the western Great Lakes, Sulpilcian missionaries François Dollier de Casson and René Bréhant de Galinée set out from Montreal with twenty-seven men in seven canoes led by two canoes of Seneca Indians

- 1670 - Jesuits establish missions on the Orinoco River in Venezuela

- 1671 - Quaker missionaries arrive in the Carolinas

- 1672 - A chieftain on Guam kills Jesuit missionary Diego Luis de San Vitores and his Visayan assistant, Pedro Calungsod, for having baptized the chief's daughter without his permission (some accounts do say the girl's mother consented to the baptism)

- 1672 Greek Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem, decreed Biblical canon

- 1673 - French trader Louis Jolliet and missionary Jacques Marquette visit what is now the state of Illinois, where the latter establishes a mission for Native Americans [36]

- 1674 - Vincentian mission to Madagascar collapses after 25 years of abortive effort [37]

- 1675 - An uprising on the islands of Micronesia leads to the death of three Christian missionaries

- 1675 Philipp Jakob Spener publishes Pia Desideria, which becomes a manifesto for Pietism

- 1676 - Kateri Tekakwitha, who became known as the Lily of the Mohawks, is baptized by a Jesuit missionary. She, along with many other Native Americans, joins a missionary settlement in Canada where a syncretistic blend of ascetic indigenous and Catholic beliefs evolves.

- 1678 John Bunyan publishes Pilgrim's Progress

- 1678 -French missionaries Jean La Salle and Louis Hennepin discover Niagara Falls

- 1679 - Writing from Changzhou, newly arrived missionary Juan de Yrigoyen describes three Christian congregations flourishing in that Chinese city [6]

- 1680 - The Pueblo Revolt begins in New Mexico with the killing of twenty-one Franciscan missionaries

- 1681 - After arriving in New Spain, Italian Jesuit Eusebio Kino soon becomes what one writer described as "the most picturesque missionary pioneer of all North America." A bundle of evangelistic zeal, Kino was also an explorer, astronomer, cartographer, mission builder, ranchman, cattle king, and defender of the frontier [38]

- 1682 - 13 missionaries go to "remote cities" in East Siberia

- 1682 Avvakum, leader of the Old Believers, burned at the stake in the Far North of Russia

- 1683 - Missionary Louis Hennepin returns to France after exploring Minnesota and being held captive by the Dakota to write the first book about Minnesota, Description de la Louisiane

- 1684 - Louis XIV of France sends Jesuit missionaries to China bearing gifts from the collections of the Louvre and the Palace of Versailles

- 1684 Roger Williams (theologian), advocate of Separation of church and state, founder of Providence, Rhode Island

- 1685 - Consecration of first Catholic bishop of Chinese origin

- 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau outlaws Protestantism in France

- 1685 Orthodoxy introduced to Beijing by Russian Orthodox Church

- 1686 - Russian Orthodox monks arrive in China as missionaries

- 1687 - French activity begins in what is now Côte d'Ivoire when missionaries land at Assinie

- 1688 - New Testament translated into the Malay language (the first Bible translation into a language of southeast Asia)

- 1689 - Calusa Indian chief from what is the state of Florida visits Cuba to discuss idea of having missionaries come to his people [7]

- 1690 - First Franciscan missionaries arrive in Texas

- 1691 - Christian Faith Society for the West Indies was organized with a focus on evangelizing African slaves [8]

- 1692 - Chinese Kangxi Emperor permits the Jesuits to freely preach Christianity, converting whom they wish

- 1692 Salem witch trials in Colonial America

- 1692–1721 Chinese Rites controversy

- 1693 - Jesuit missionary John de Britto is publicly beheaded in India

- 1693 Jacob Amman founder of Amish

- 1694 - Missionary and explorer Eusebio Kino becomes the first European to enter the Tucson, Arizona basin and create a lasting settlement

- 1695 - China's first Russian Orthodox church building is consecrated

- 1696 - Jesuit missionary François Pinet founds the Mission of the Guardian Angel near what is today Chicago. The mission was abandoned in 1700 when missionary efforts seemed fruitless

- 1697 - To evangelize the English colonies, Thomas Bray, an Anglican preacher who made several missionary trips to North America, begins laying the groundwork for what will be the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts [39]

- 1698 - Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge organized by Anglicans [28]

- 1699 - Priests of the Quebec Seminary of Foreign Missions establish a mission among the Tamaroa Indians at Cahokia in what is now the state of Illinois

- 1700 - After a Swedish missionary's sermon in Pennsylvania, one Native American posed such searching questions that the episode was reported in a 1731 history of the Swedish church in America. The interchange is noted in Benjamin Franklin's Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America (1784). [9]

References

- ^ (fascimile Dedicatorie): "And now at last, ...it being brought unto such a conclusion, as that we have great hope that the Church of England (sic) shall reape good fruit thereby..."

- ^ Lortz, IV, 7-11

- ^ Duffy 188-189

- ^ W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (1997), p. 50, p. 86 etc.

- ^ Roland Mousnier, The Assassination of Henry IV: The Tyrannicide Problem and the Consolidation of the French Absolute Monarchy in the Early 17th Century, Part II (1973 English translation)

- ^ http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/encyc08/Page_353.html

- ^ Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic

- ^ Michael Sharratt, Galileo: Decisive Innovator (2000), p. 109.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 540

- ^ F Zöpfl, Barocke Frömmigkeit, in Marienkunde, 577

- ^ Zöpfl 579

- ^ a b Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), pp. 188–91

- ^ Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church (2004), pp. 267–9

- ^ Franzen 326

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 137

- ^ Franzen 323

- ^ Tucker, 2004, 69

- ^ Kane, p. 64

- ^ Anderson, 399

- ^ a b Kane, 68

- ^ a b Barrett, p. 27

- ^ Herbermann, p. 456

- ^ Delaney, John J. and James Edward Tobin. Dictionary of Catholic Biography, Doubleday, 1961, p. 227

- ^ Latourette, 1941, vol. III, p. 277

- ^ Henze, p. 99

- ^ a b Latourette, 1941, vol. III, p. 176

- ^ Tucker, 2004, p. 75

- ^ a b Kane, p. 82

- ^ Olson, p. 115

- ^ Latourette, 1941, vol. III, p. 164

- ^ Tucker, 2004, p. 78

- ^ Kane, p. 69

- ^ Kane, p. 76

- ^ Glover, 55

- ^ Elliot, Elisabeth. Through Gates of Splendor, Tyndale House Publishers, 1986, p. 15

- ^ Herbermann, p. 388

- ^ Gow, Bonar. Madagascar and the Protestant Impact: The Work of the British Missions, 1818-95, Dalhousie University Press, 1979, p. 2.

- ^ Anderson, 367

- ^ Latourette, 1941, vol. III, p. 189

Further reading

- Esler, Phillip F. The Early Christian World. Routledge (2004). ISBN 0415333121.

- White, L. Michael. From Jesus to Christianity. HarperCollins (2004). ISBN 0060526556.

- Freedman, David Noel (Ed). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (2000). ISBN 0802824005.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press (1975). ISBN 0226653714.

External links

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of Protestantism

- History of the Roman Catholic Church#Baroque, Enlightenment and revolutions

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church#Ottoman Empire

- History_of_Christian_theology#Renaissance and Reformation

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Timeline of the English Reformation

- Timeline of Christianity#17th century

- Timeline of Christian missions#1600 to 1699

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#1600–1800

- Chronological list of saints and blesseds in the 17th century

- Timeline of 17th century Muslim history

History of Christianity: The Reformation Preceded by:

Christianity in

the 16th century17th

CenturyFollowed by:

Christianity in

the 18th centuryBC 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th 18th 19th 20th 21st Categories:- History of Christianity

- 17th-century Christianity

- Early Modern history of Christianity

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.