- Christianity in the 1st century

-

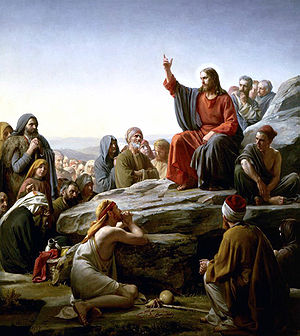

Christians believe that Jesus is the mediator of the New Covenant.[1] Depicted by 19th century Danish painter Carl Heinrich Bloch is his Sermon on the Mount (c. 30) in which he Expounds on the Law. Some scholars consider this to be an antitype of the proclamation of the Ten Commandments or Mosaic Covenant by Moses from the Biblical Mount Sinai.[2]

Christians believe that Jesus is the mediator of the New Covenant.[1] Depicted by 19th century Danish painter Carl Heinrich Bloch is his Sermon on the Mount (c. 30) in which he Expounds on the Law. Some scholars consider this to be an antitype of the proclamation of the Ten Commandments or Mosaic Covenant by Moses from the Biblical Mount Sinai.[2] Main article: Early history of Christianity

Main article: Early history of ChristianityThe earliest followers of Jesus composed an apocalyptic, Jewish sect, which historians refer to as Jewish Christianity.[3] The Apostles and others following the Great Commission's decree to spread the teachings of Jesus to "all nations," had great success spreading the religion to gentiles. Peter, Paul, and James the Just were the most notable of Early Christian leaders.[4] Though Paul's influence on Christian thinking is said to be more significant than any other New Testament author,[5] the relationship of Paul of Tarsus and Judaism is still disputed today. Rather than having a sudden split, early Christianity gradually grew apart from Judaism as a predominantly gentile religion.

Christian restorationists propose that the 1st century Apostolic Age represents a purer form of Christianity that should be restored in the church as it exists today.

Contents

Life and Ministry of Jesus

Main article: JesusSee also: Ministry of Jesus, Gospel harmony, New Testament view on Jesus' life, and Chronology of Jesus 18th century painting, The Crucifixion, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

18th century painting, The Crucifixion, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

The ministry of Jesus, according to the account of the Gospels, falls into this pattern of sectarian preachers with devoted disciples. According to the Gospel writers, after being baptized by John the Baptist, Jesus preached for a period of one to three years when he was in his early 30s, in the early 1st century AD. The gospels give Jesus' method of teaching as involving parables, metaphor, allegory, sayings, proverbs, and a small number of direct sermons such as the Sermon on the Mount. His ministry was cut short by his execution at the hands of the Roman authorities in Jerusalem, but see also Responsibility for the death of Jesus. This event, cast in terms of substitutionary atonement, possibly motivated his surviving disciples to embark on a number of missionary campaigns to spread the "Good News"[citation needed], though literally they were simply following Jesus' Great Commission to spread the teachings of Jesus to "all nations".

The account of the Gospels tells us that Jesus was born to a Jewish mother named Mary in 6-4 BC and that he was raised in Nazareth, Galilee and lived for a short time in Egypt. His ministry around the age of thirty and that it included recruiting disciples who regarded him as a wonderworker, healer and/or the Son of Man and Son of God. He was eventually executed by crucifixion in Jerusalem c. AD 33 on orders of the Roman Governor of Iudaea Province, Pontius Pilate;[6] and after his crucifixion,[7] Jesus was buried in a tomb.[8]

Christians believe that three days after his death, Jesus and his body rose from the dead and that the empty tomb story is a historical fact.[9] Early works by Jesus's followers document a number of resurrection appearances and[10] the resurrection of Jesus formed the basis and impetus of the Christian faith.[11] His followers wrote that he appeared to the disciples in Galilee and Jerusalem and that Jesus was on the earth for 40 days before his Ascension to heaven[12] and that he will return to earth again to fulfil aspects of Messianic prophecy, such as the resurrection of the dead, the last judgment and the full establishment of the Kingdom of God, though Preterists believe these events have already happened.

The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical gospels, and to a lesser extent the Acts of the Apostles and writings of Paul. Christianity's popularity is largely founded and based on one central point found in these Gospels, that Jesus died and rose from death as God's sacrifice for human sins,[13] see also Substitutionary atonement.

Jesus began his ministry after his baptism by John the Baptist and during the rule of Pontius Pilate, preaching: "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near."[14] While the historicity of the gospel accounts is questioned to some extent by some critical scholars and non-Christians, those accounts detail the following chronology for his ministry: his temptation in the wilderness, the Sermon on the Mount, the appointment of the Twelve, many miracles and teachings, the Last Supper with the Twelve, the arrest and trial of Jesus, his suffering and crucifixion on Good Friday[15] entombment, resurrection on Easter Sunday, various resurrection appearances, giving the Great Commission, and his Ascension from the Mount of Olives with a promise to return. See the Gospel harmony for more details.

Apostolic Age: Post-Jesus Christianity

Main article: Apostolic AgeEarly Christianity may be divided in two distinct phases: the apostolic period, when the apostles were leading the Church, and the post-apostolic period or ante-Nicene period, when imperial persecution of Christians continued until the rise of Constantine the Great, and the early episcopate developed until the First Council of Nicaea in 325 and the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils.

The years following Jesus until the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles is called the Apostolic Age.[16] The Christian Church came fully into being on Pentecost when, according to scriptural accounts, the apostles received the Holy Spirit and emerged from hiding following the death and resurrection of Jesus to preach and spread his message.[17][18] The apostolic period produced writings attributed to the direct followers of Jesus Christ and is traditionally associated with the apostles and apostolic times. This age is the foundation upon which the entire church's history is founded.[19] This Apostolic Church, also called the "Primitive Church", was the community led by Jesus' apostles and, it would seem, his relatives.[20]

Acts of the Apostles

The Cenacle on Mount Zion, claimed to be the location of the Last Supper and Pentecost. Bargil Pixner[21] claims the original Church of the Apostles is located under the current structure.

The principal source of information for this earliest period is the Acts of the Apostles, which gives a history of the Church from the resurrected Jesus' commission to the disciples to spread his teachings to all nations,[22] Pentecost,[23] and the spread of the Christian faith outside of the Jewish nation and among the gentiles.[24] However, there are scholars who dispute the Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles.

Soon after the earthly ministry of Jesus, the Jerusalem church started up at Pentecost with Apostles and others totalling some 120 Jews and Jewish Proselytes,[25] in an "upper room," believed by some to be the Cenacle, and thus "the first Christian church."[26] The Acts of the Apostles goes on to record the stoning of Stephen and the subsequent dispersal of the church;[27] which led to the baptism of Simon Magus in Samaria;[28] and also an Ethiopian eunuch.[29] Paul's "Road to Damascus" conversion to the "Apostle to the Gentiles" is first recorded in Acts 9:13-16.[30] Peter baptized the Roman Centurion Cornelius, traditionally considered the first Gentile convert to Christianity, in Acts 10.[31] The Antioch church was founded and it was there that the term Christian was coined.[32]

Disputes over the Mosaic law generated intense controversy in early Christianity.[33] This is particularly notable in the mid-1st century, when the circumcision controversy came to the fore. The issue was addressed at the Council of Jerusalem where Paul made an argument that circumcision was not a necessary practice, vocally supported by Peter, as documented in Acts 15.[34] This position received widespread support and was summarized in a letter circulated in Antioch. Four years after the Council of Jerusalem, Paul wrote to the Galatians about the issue, which had become a serious controversy in their region. According to Alister McGrath, Paul considered it a great threat to his doctrine of salvation through faith and addressed the issue with great detail in Galatians 3.[35][36]

Although competing forms of Christianity emerged early and persisted into the 5th century, there was broad doctrinal unity within the mainstream churches.[37][38] Bishops like Ignatius of Antioch (c.35-c.108) and later Irenaeus (d. c.202) defined proto-orthodox teaching in stark opposition to heresies such as Gnosticism.[39]

In spite of intermittent intense persecutions, the Christian religion continued its spread throughout the Mediterranean Basin.

Worship of Jesus

The sources for the beliefs of the apostolic community include the Gospels and New Testament Epistles. The very earliest accounts are contained in these texts, such as early Christian creeds and hymns, as well as accounts of the Passion, the empty tomb, and Resurrection appearances; often these are dated to within a decade or so of the crucifixion of Jesus, originating within the Jerusalem Church.[40]

The earliest Christian creeds and hymns express belief in the risen Jesus, e.g., that preserved in 1 Corinthians 15:3–4[41] quoted by Paul: "For I delivered to you first of all that which I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures."[42] The antiquity of the creed has been located by many scholars to less than a decade after Jesus' death, originating from the Jerusalem apostolic community,[43] and no scholar dates it later than the 40s.[44] Other relevant and very early creeds include 1 John 4:2,[45][46] 2 Timothy 2:8,[47][48] Romans 1:3–4,[49][50] and 1 Timothy 3:16,[51] an early creedal hymn.[52]

Persecutions

See also: Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire and Persecution of early Christians by the RomansFrom the beginning, Christians were subject to various persecutions. This involved even death for Christians such as Stephen (Acts 7:59) and James, son of Zebedee (12:2). Larger-scale persecutions followed at the hands of the authorities of the Roman Empire, beginning with the year 64, when, as reported by the Roman historian Tacitus, the Emperor Nero blamed them for that year's great Fire of Rome.

Several of the New Testament writings mention persecutions and stress endurance through them. Christians suffered persecutions for their refusal to give any worship to the Roman emperor, considered treasonous and punishable by execution.

Systematic persecution of the early Christian church caused it to be an underground movement. Of the underground churches that existed before legalization, some are recorded to have existed as the catacombs in Europe, Catacombs of Rome, Greece (see Cave of the Apocalypse, The Church of St George and the church at Pergamon) and also in the underground cities of Anatolia such as Derinkuyu Underground City (also see Cave monastery and Bab Kisan).

Jerusalem in Christianity

Main article: Jerusalem in ChristianityShortly after the death and resurrection, and ascension of Jesus, the Jerusalem church was founded as the first Christian church with about 120 Jews and Jewish Proselytes (Acts 1:15), at Pentecost. The Christian community in Jerusalem, where Jesus, many of the twelve Apostles and many eye-witnesses originally lived, had a special position among Christian communities. It experienced conflict and persecution especially in the years 32-33 and 62-63 highlighted by the stoning of Stephen and the death of the James, son of Zebedee.[53]

The Desposyni (relatives of Jesus) lived in Nazareth during the 1st century. The relatives of Jesus were accorded a special position within the early church, as displayed by the leadership of James the Just in Jerusalem.[54]

The destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70, seen as symbolic by Supersessionism, and the consequent dispersion of Jews and Jewish Christians from this city (after the Bar Kokhba revolt), ended any pre-eminence of the Jewish-Christian leadership in Jerusalem (see Bishops of Aelia Capitolina and Jerusalem in Christianity). Although Epiphanius of Salamis reported that the Cenacle itself survived at least to Hadrian's visit in 130,[55] some today think it merely rebuilt shortly after this first Jewish war.[21] Early Christianity grew further apart from Judaism to establish itself as a predominantly gentile religion, and Antioch became the first Gentile Christian community with stature.[56]

Peter and the Twelve

Today, New Testament scholars agree that there is a special position to Peter among the Twelve. The official Catholic Church position is that Jesus had essentially appointed Peter as the first Pope, with authority over the entire Church.[57] This is derived from his seeming primacy among the Twelve in New Testament texts on Peter, namely Matthew 16:17-19, Luke 22:32, and John 21:15-17.

The Christian Church built its identity on the Apostles as witnesses to Christ, and responsibility for pastoral leadership was not restricted to Peter. The New Testament also does not contain any record of the transmission of Peter's leadership, nor is the transmission of apostolic authority in general very clear. As a result, the New Testament texts on Peter have been subjected to differing interpretations from the time of the Church Fathers on.

Irenaeus of Lyons believed in the 2nd century that Peter and Paul had been the founders of the Church in Rome and had appointed Linus as succeeding bishop.[58] There is no conclusive evidence, scripturally, historically or chronologically, that Peter was in fact the Bishop of Rome. While the church in Rome was already flourishing when Paul wrote his Epistle to the Romans to them from Corinth, about AD 57,[59] he greets some fifty people in Rome by name,[60] but not Peter whom he knew. There is also no mention of Peter in Rome later during Paul's two year stay there in chapter 28 of Acts, about AD 60-62. Church historians consistently consider Peter and Paul to have been martyred under the reign of Nero,[2][61][62] around AD 65 such as after the Great Fire of Rome which, according to Tacitus, Nero blamed on the Christians.[63]

Worship Liturgy

See also: Eastern Orthodox Worship and Divine LiturgyLiturgical services and in specific the Eucharist service, are based on repeating the actions of Jesus ("do this in remembrance of me"), using the bread and wine, and saying his words (known as the words of the institution). The church has the rest of the liturgical ritual being rooted in the Jewish Passover, Siddur, Seder, and synagogue services, including the singing of hymns (especially the Psalms) and reading from the Scriptures.[64] Clement writes that liturgies are "to be celebrated, and not carelessly nor in disorder" but the final uniformity of liturgical services only came later, though the Liturgy of St James is traditionally associated with James the Just.[65] Also noteworthy is the so-called Clementine Liturgy found in the eighth book of the Apostolic Constitutions and proposed by some to be of early origin.[66]

Earliest Christianity took the form of a Jewish eschatological faith. The book of Acts reports that the early followers continued daily Temple attendance and traditional Jewish home prayer. Other passages in the New Testament gospels reflect a similar observance of traditional Jewish piety such as fasting, reverence for the Torah and observance of Jewish holy days. The earliest form of Jesus's religion is best understood in this context.[67][68] At first, Christians continued to worship alongside Jewish believers, but within twenty years of Jesus's death, Sunday (the Lord's Day) was being regarded as the primary day of worship.[69]

Defining scripture

Main article: Development of the Christian Biblical canonThe early Christians likely did not have their own copy of Scriptural and other church works. Much of the original church liturgical services functioned as a means of learning Christian theology later expressed in these works.

Christianity first spread in the predominantly Greek-speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire, and then extensively throughout the Empire by Paul and others. Ecclesiastical historian Henry Hart Milman writes that in much of the first three centuries, even in the Latin-dominated western empire: "the Church of Rome, and most, if not all the Churches of the West, were, if we may so speak, Greek religious colonies [see Greek colonies for the background]. Their language was Greek, their organization Greek, their writers Greek, their scriptures Greek; and many vestiges and traditions show that their ritual, their Liturgy, was Greek."[70]

Old Testament

Main article: Development of the Old Testament canonThe Biblical canon began with the Jewish Scriptures, first available in Koine Greek translation, then as Aramaic Targums. In the 2nd century, Melito of Sardis called these Scriptures the "Old Testament",[71] and specified an early canon. The Greek translation, later known as the Septuagint[72] and often written as "LXX," arose from Hellenistic Judaism which predates Christianity. Perhaps the earliest Christian canon is the Bryennios List which was found by Philotheos Bryennios in the Codex Hierosolymitanus. The list is written in Koine Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew and dated to around 100 by J. P. Audet.[73] It consists of a 27-book canon which comprises:

“ Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Jesus Nave,[74] Deuteronomy, Numbers, Judges, Ruth, 4 of Kings (Samuel and Kings), 2 of Chronicles, 2 of Esdras, Esther, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Job, Minor prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel. ” New Testament

Books of the

New Testament

Gospels Matthew · Mark · Luke · John Acts Acts of the Apostles Epistles Romans

1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians

Galatians · Ephesians

Philippians · Colossians

1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians

1 Timothy · 2 Timothy

Titus · Philemon

Hebrews · James

1 Peter · 2 Peter

1 John · 2 John · 3 John

JudeApocalypse Revelation New Testament manuscripts Main article: Development of the New Testament canonThe "New Testament" (often compared to the New Covenant) is the name given to the second major division of the Christian Bible, either by Tertullian or Marcion in the 2nd century.[75] The original texts were written by various authors, most likely sometime after c. AD 45 in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, though there is also a minority argument for Aramaic primacy.

The common languages spoken by both Jews and Gentiles in the Holy Land at the time of Jesus were Aramaic, Koine Greek, and to a limited extent a colloquial dialect of Mishnaic Hebrew. It is generally believed that the original text of the New Testament was written in Koine Greek, the vernacular dialect in the 1st century Roman provinces of the Eastern Mediterranean, and later translated into other languages, most notably, Latin, Syriac, and Coptic. However, some of the Church Fathers seem to imply that Matthew was originally written in Hebrew or Aramaic, and there is another contention that the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews wrote in Hebrew, which was translated into Greek by Luke. Neither view holds much support among contemporary scholars, who argue that the literary facets of Matthew and Hebrews suggest that they were composed directly in Greek, rather than being translated, a view known as Greek primacy.

Gospels and Acts

See also: Synoptic problemEach of the gospels narrates the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. The first three are commonly classified as the Synoptic Gospels. They contain very similar accounts of events in Jesus' life. The Gospel of John describes several miracles and sayings of Jesus not found in the other three. The synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, unlike the other New Testament works, have a unique interrelationship. The dominant view among non-theologian scholars is the Two-Source Hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that both Matthew and Luke drew significantly upon the Gospel of Mark and another common source, known as the "Q Source" (Q is derived from Quelle, the German word for "source"). However, the nature and even existence of Q is speculative, and scholars have proposed variants on the hypothesis which redefine or exclude it.[76] Most pro-Q scholars believe that it was a single written document, while a few contest that "Q" was actually a number of documents or oral traditions. If it was a documentary source, no information about its author or authors can be obtained from the resources currently available. The common view supposes that Mark was written first, and Matthew and Luke drew from it and the second chronological work; and some scholars have attempted to use their modern methods to confirm the idea.

While each work is internally anonymous; the traditional author is listed after each entry.

- The Gospel of Matthew is traditionally ascribed to the Apostle Matthew, according to Papias, Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus[77] and Eusebius.[5][78]

- The Gospel of Mark is traditionally ascribed to John Mark the Evangelist, who wrote down the recollections of the Apostle Simon Peter according to Papias, Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus, and Eusebius.[79]

- The Gospel of Luke is traditionally ascribed to Luke, a physician and companion of the Apostle Paul according to Clement of Alexandria, and the Muratorian fragment.[80][81]

- The book of Acts, is a sequel to the third gospel. Examining style, phraseology, and other evidence, modern scholarship agrees that Acts and Luke share the same author.

- The Gospel of John is traditionally ascribed to the Apostle John, son of Zebedee according to Papias, Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus, Eusebius,[5] the Muratorian fragment, the Codexes Alexandrinus and Vaticanus.

The New Testament is a collection of works, and as such was written by multiple authors. The traditional view is that all the books were written by apostles (e.g. Matthew and Paul), or disciples working under their direction (e.g. Mark[82] and Luke[83]). However, in modern times, with the rise of rigorous historical inquiry and textual criticism, these traditional ascriptions have been rejected by some. While the traditional authors have been listed above, a modern, unsubstantiated critical view is discussed herein.

Epistles

General epistles includes those epistles written to the church at large.

-

- The Pauline epistles constitute those epistles traditionally attributed to Paul.

- Traditionally ascribed to James the Just, brother of Jesus and Jude Thomas.

- Traditionally ascribed to the Apostle Simon, called Peter.

- Traditionally ascribed to the Apostle John, son of Zebedee. He was the last Apostle to have died, in Ephesus of Asia Minor, about 100 AD.

- Traditionally ascribed to Jude Thomas, brother of Jesus and James the Just.

- Unknown authorship. While some the work listed below to be traditionally by Paul, modern scholars agree with Origen (d. 254) "who wrote the epistle, God only knows".[85][86]

Main articles: Authorship of the Pauline epistles and Authorship of the Johannine worksSeven of the epistles of Paul are generally accepted by most modern scholars as authentic; these undisputed letters include Romans, First Corinthians, Second Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, First Thessalonians, and Philemon. Liberal scholars usually question Pauline authorship for any other epistle, although there are conservative Christian scholars who accept the traditional ascriptions. However, almost no current mainstream scholars, Christian or otherwise, hold that Paul wrote Hebrews. In fact, questions about the authorship of Hebrews go back at least to the 3rd century ecclesiastical writer Caius, who attributed only thirteen epistles to Paul (Eusebius, Hist. eccl., 6.20.3ff.). A small minority of scholars hypothesize Hebrews may have been written by one of Paul's close associates, such as Barnabas, Silas, or Luke, given that the themes therein seemed to them as largely Pauline.

The authorship of all non-Pauline books have been disputed in recent times. Ascriptions are largely polarized between Christian and non-Christian experts, making any sort of scholarly consensus all but impossible. Even majority views are unclear.

A Clement's letter to the church at Corinth in 95 quotes from 10 of the 27 books of the New Testament, and a Polycarp's letter to the Philippians in 120 quotes from 16 books. An early datation has been proposed by John A. T. Robinson, on the ground that none of the writings in the New Testament showed clear evidence of a knowledge of Jerusalem's Temple's destruction, which should have appeared considering the importance of that event for Jews and Christians of that time. Thus, he argues that the whole New Testament have been written before 70 AD.[87]

Early Christianity and Judaism

Painting by Rembrandt of Paul, one of the most notable of early Christian missionaries, who called himself the "Apostle to the Gentiles." Paul, a Hellenistic Jew, was very influential on the shift of Christianity to Gentile dominated movement.

Painting by Rembrandt of Paul, one of the most notable of early Christian missionaries, who called himself the "Apostle to the Gentiles." Paul, a Hellenistic Jew, was very influential on the shift of Christianity to Gentile dominated movement.

Jewish messianism has its roots in the apocalyptic literature of the 2nd to 1st century BC, promising a future "anointed" leader or Messiah to resurrect the Israelite "Kingdom of God", in place of the foreign rulers of the time. This corresponded with the Maccabean Revolt directed against the Seleucids. Following the fall of the Hasmonean kingdom, it was directed against the Roman administration of Iudaea Province, which, according to Josephus, began with the formation of the Zealots during the Census of Quirinius of 6 AD.

Jewish continuity

See also: Rejection of Jesus, Biblical law in Christianity, Sabbath in Christianity, and Paul of Tarsus and JudaismThe early Christians in the 1st century AD believed Yahweh to be the Only true God,[88] the God of Israel, and considered Jesus to be the Messiah (Christ) prophesied in the Jewish Scriptures. The first Christians were essentially all ethnically Jewish or Jewish Proselytes. In other words, Jesus preached to the Jewish people and called from them his first disciples, known as the Limited Commission of Matthew 10:5-42, while the Great Commission issued after the Resurrection is specifically directed at "all nations".

Alister McGrath, a proponent of palaeo-orthodoxy, claimed that many of the Jewish Christians were fully faithful religious Jews, only differing in their acceptance of Jesus as the Messiah.[89] Acts records the martyrdom of Stephen and James. Thus, Christianity acquired an identity distinct from Rabbinic Judaism. The name "Christian" (Greek Χριστιανός) was first applied to the disciples in Antioch, as recorded in Acts 11:26.[90]

Early Christianity retained some of the doctrines and practices of 1st-century Judaism while rejecting others. They held the Jewish scriptures to be authoritative and sacred, employing mostly the Septuagint or Targum translations, later called the Old Testament, a term associated with Supersessionism, and added other texts as the New Testament canon developed. Christianity also continued other Judaic practices: baptism,[91] liturgical worship, including the use of incense, an altar, a set of scriptural readings adapted from synagogue practice, use of sacred music in hymns and prayer, and a religious calendar, as well as other distinctive features such as an exclusively male priesthood, and ascetic practices (fasting etc.). Circumcision was rejected as a requirement at the Council of Jerusalem, c. 50, though the decree of the council parallels Jewish Noahide Law. Sabbath observance was modified, perhaps as early as Ignatius' Epistle to the Magnesians 9.1.[92] Quartodecimanism (observation of the Paschal feast on Nisan 14, the day of preparation for Passover, linked to Polycarp and thus to John the Apostle) was formally rejected at the First Council of Nicaea.

An early difficulty arose concerning the matter of Gentile (non-Jewish) converts as to whether they had to "become Jewish," in following circumcision and dietary laws, as part of becoming Christian. Circumcision was considered repulsive during the period of Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean.[93] The decision of Peter, as evidenced by conversion of the Centurion Cornelius,[94] was that they did not, and the matter was further addressed with the Council of Jerusalem. Around this same time period, Rabbinic Judaism made their circumcision requirement even stricter.[95]

The doctrines of the apostles brought the Early Church into conflict with some Jewish religious authorities. Late 1st century developments attributed to the Council of Jamnia eventually led to Christian's expulsion from synagogues.

Jewish Christians

Main article: Jewish Christians James the Just, whose judgment was adopted in the Apostolic Decree of Acts 15:19-29, "...we should write to them [Gentiles] to abstain only from things polluted by idols and from fornication and from whatever has been strangled and from blood..." (NRSV)

James the Just, whose judgment was adopted in the Apostolic Decree of Acts 15:19-29, "...we should write to them [Gentiles] to abstain only from things polluted by idols and from fornication and from whatever has been strangled and from blood..." (NRSV)

Jewish Christians were among the earliest followers of Jesus and an important part of Judean society during the mid to late 1st century. This movement was centered around Jerusalem and led by James the Just. They held faithfully to the Torah (perhaps also Jewish law which was being formalized at the same time), including acceptance of Gentile converts based on a version of the Noachide laws (Acts 15 and Acts 21). In Christian circles, "Nazarene" later came to be used as a label for those faithful to Jewish law, in particular for a certain sect. These Jewish Christians, originally the central group in Christianity, were not at first declared to be unorthodox, but were later excluded and denounced. Some Jewish Christian groups, such as the Ebionites, were considered to have unorthodox beliefs, particularly in relation to their views of Christ and Gentile converts. The Nazarenes, holding to orthodoxy except in their adherence to Jewish law, were not deemed heretical until the dominance of orthodoxy in the 4th century. The Ebionites may have been a splinter group of Nazarenes, with disagreements over Christology and leadership. After the condemnation of the Nazarenes, "Ebionite" was often used as a general pejorative for all related "heresies".[96][97]

Jewish Christians constituted a separate community from the Pauline Christians, but maintained a similar faith, differing only in practice. There was a post-Nicene "double rejection" of the Jewish Christians by both Gentile Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. It is believed that there was no direct confrontation, or persecution, between Gentile and Judaic Christianity. However, by this time the practice of Judeo-Christianity was diluted, both by internal schisms and external pressures. Some[who?] claim the true end of ancient Jewish Christianity occurred only in the 5th century.[citation needed] According to this theory, those remaining fully faithful to Halacha became purely Jews, while those adhering to the Christian faith joined with Pauline Christianity. Gentile Christianity remained the sole strand of orthodoxy and imposed itself on the previously Jewish Christian sanctuaries, taking full control of those houses of worship by the end of the 5th century.[98]

The Nasrani or Syrian Malabar Nasrani community in Kerala, India is conscious of their Jewish origins. However, they have lost many of their Jewish traditions due to western influences. The Nasrani are also known as Syrian Christians or St. Thomas Christians. This is because they follow the traditions of Syriac Christianity and are descendants of the early converts by St. Thomas the Apostle. Today, they belong to various denominations of Christianity but they have kept their unique identity within each of these denominations.[99]

Split with Judaism

In or around the year 50, the apostles convened the first church council, known as the Council of Jerusalem, to reconcile practical (and by implication doctrinal) differences concerning the Gentile mission.[100] While not numbered among them, this council has often been looked to as both "ecumenical" and the model for later ecumenical councils.

At the Council of Jerusalem it was agreed that gentiles could be accepted as Christians without full adherence to the Mosaic Laws, possibly a major break between Christianity and Judaism (the first being the Rejection of Jesus[101]), though the decree of the council (Acts 15:19-29) seems to parallel the Noahide laws of Judaism, see also Jewish background to the early Christian circumcision controversy. The Council of Jerusalem, according to Acts 15, determined that circumcision was not required of Gentile converts, only avoidance of "pollution of idols, fornication, things strangled, and blood" (KJV, Acts 15:20), establishing nascent Christianity as an attractive alternative to Judaism for prospective Proselytes. The Twelve Apostles and the Apostolic Fathers initiated the process of integration of the originally Jewish sect (outlawed as religio illicita since the 80s, assuming they didn't pay the Fiscus Judaicus) into a more Hellenistic religion.

There was a slowly growing chasm between Christians and Jews, rather than a sudden split. Even though it is commonly thought that Paul established a Gentile church, it took centuries for a complete break to manifest. However, certain events are perceived as pivotal in the growing rift between Christianity and Judaism. The Council of Jamnia c. 85 is often stated to have condemned all who claimed the Messiah had already come, and Christianity in particular. However, the formulated prayer in question (birkat ha-minim) is considered by other scholars to be unremarkable in the history of Jewish and Christian relations. There is a paucity of evidence for Jewish persecution of "heretics" in general, or Christians in particular, in the period between 70 and 135. It is probable that the condemnation of Jamnia included many groups, of which the Christians were but one, and did not necessarily mean excommunication. That some of the later church fathers only recommended against synagogue attendance makes it improbable that an anti-Christian prayer was a common part of the synagogue liturgy. Jewish Christians continued to worship in synagogues for centuries.[102][103][104]

During the late 1st century, Judaism was a legal religion with the protection of Roman law, worked out in compromise with the Roman state over two centuries. Observant Jews had special rights, including the privilege of abstaining from civic pagan rites. Christians were initially identified with the Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for Roman rulers. Circa 98 the emperor Nerva decreed that Christians did not have to pay the annual tax upon the Jews, effectively recognizing them as distinct from Rabbinic Judaism. This opened the way to Christians being persecuted for disobedience to the emperor, as they continued to refuse to worship the state pantheon. It is notable that from c. 98 onwards a distinction between Christians and Jews in Roman literature becomes apparent. For example, Pliny the Younger postulates that Christians are not Jews since they do not pay the tax, in his letters to Trajan.[105][106][107]

According to the account by Cornelius Tacitus' in his Annals, Christians were a group punished for the Great Fire of Rome, in order to divert blame from Nero. The original text of the earliest extant manuscript, from which the other existing manuscripts probably are derived, suggests that Tacitus wrote "Chrestianos", which was a vulgar form of the name "Christianos", likely derived from the most common name for slaves ("Chrestus", which means "useful"). In the same passage Tacitus used the name "Christus", not "Chrestus", to refer to the founder of the "Chrestianos", noting that he was a Jew executed as a criminal under Pontius Pilate.[108]

Spread of Christianity

Mediterranean Basin geography relevant to Paul's life, stretching from Jerusalem in the lower right to Rome in the upper left.

Mediterranean Basin geography relevant to Paul's life, stretching from Jerusalem in the lower right to Rome in the upper left. See also: Early centers of Christianity

See also: Early centers of ChristianityPaul and the Apostles traveled extensively and establishing communities in major cities and regions throughout the Empire. The first communities, outside of Jerusalem, appeared in Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth, and the political center of Rome. The original church communities were founded by apostles and numerous other Christians, soldiers, merchants, and preachers[109] in northern Africa, Asia Minor, Arabia, Greece, and other places.[17][110][111] Over 40 were established by the year 100,[110][111] many in Asia Minor, see also Seven Churches of Asia.

Paul was responsible for bringing the Christianity to new parts of the world such as Ephesus, Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica.[112][113] By the end of the 1st century, Christianity had already spread to Rome and to various cities in Greece, Asia Minor and Syria. Major cities such as Rome, Ephesus, Antioch and Corinth served as foundations for the expansive spread of Christianity in the post-apostolic period. Christianity spread quickly throughout Asia Minor. In Syria, it reached Edessa during this era, spurring the development of various local Christian legends.

Apostolic Fathers

Main article: Apostolic FathersThe Church Fathers are the early and influential theologians and writers in the Christian Church, particularly those of the first five centuries of Christian history. The earliest Church Fathers, within two generations of the Apostles of Christ, are usually called Apostolic Fathers, for reportedly knowing and studied under the apostles personally. Important Apostolic Fathers include Clement of Rome,[114] Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna. In addition, the Didache and Shepherd of Hermas are usually placed among the writings of the Apostolic Fathers although their authors are unknown.

Clement of Rome

Main article: Clement of RomeClement of Rome was best known for his letter: 1 Clement (c. 96),[114] which was held in high regard by later Christian writers and even cited as Scripture by Clement of Alexandria.[115] In it, Clement calls on the Christians of Corinth to maintain harmony and order.[114] It is the earliest Christian epistle outside the New Testament, indeed it is even included in the Codex Alexandrinus and in the Canons of the Apostles, and today is part of the Apostolic Fathers collection. Tertullian identifies him as the fourth Bishop of Rome, later called Pope. Some see his epistle as an assertion of Rome's authority over the church in Corinth and, by implication, the beginnings of papal supremacy.[116]

Clement, wrote about the order with which Jesus commanded the affairs of the Church be conducted, and the selection of persons was also "by His supreme will determined."[117] Clement also refers the way "rivalry ... concerning the priesthood" was resolved by or through Moses in chapter 43 of the letter, and in chapter 44, that likewise, the apostles "gave instructions, that when these should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed them in their ministry."

The New Testament writers use the terms "overseer" and "elders" interchangeably. Clement also refers to the leaders of the Corinthian church in his letter Clement I as bishops and presbyters interchangeably, and likewise says that the bishops are to lead God's flock by virtue of the chief shepherd (presbyter), Jesus Christ.

Bishops eventually emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations in the early church, and a hierarchical clergy gradually took the form of epískopos (overseers, bishops), then elders and presbyters (shepherds), and third were deacons (servants). But this emerged slowly and at different times for different locations.

The Didache

Main article: DidacheThe Didache is the common name of a brief early Christian treatise dated by most scholars to the late 1st century.[118] It is an anonymous work not belonging to any single individual, and a pastoral manual "that reveals more about how Jewish-Christians saw themselves and how they adapted their Judaism for gentiles than any other book in the Christian Scriptures."[119] The text, parts of which may have constituted the first written catechism, has three main sections dealing with Christian lessons, rituals such as baptism and eucharist, and Church organization. It was considered by some of the Church Fathers as part of the New Testament[120] but rejected as spurious or non-canonical by others,[121] eventually not accepted into the New Testament canon. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church however, does include the later Didascalia within its "broader canon" (though only the "narrower canon" has printed since 20th century), and the Didascalia was influenced by the Didache.[122]

The manuscript is commonly referred to as the Didache. This is short for the header found on the document and the title used by the Church Fathers, "The Lord's Teaching of the Twelve Apostles" which Jerome said was the same as the Gospel according to the Hebrews. A fuller title or subtitle is also found next in the manuscript, "The Teaching of the Lord to the Gentiles[123] by the Twelve Apostles."

Jonathan Draper writes: "Few scholars now date the text later than the end of the first century or the first few decades of the second."[118] Similarly Michael W. Holmes concurs: "A date considerably closer to the end of the first century seems more probable."[124] The 2005 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church comments: "Although in the past many English and American scholars tended to assign it to the late second century, most scholars now place at some point during the mid to late first century."[125]

The contents may be divided into four parts, which most scholars agree were combined from separate sources by a later redactor: the first is the Two Ways, the Way of Life and the Way of Death (chapters 1-6); the second part is a ritual dealing with baptism, fasting, and Communion (chapters 7-10); the third speaks of the ministry and how to deal with traveling prophets (chapters 11-15); and the final section (chapter 16) is a brief apocalypse.

1st century TimelineEarliest dates must all be considered approximate

- 6 Herod Archelaus deposed by Augustus; Samaria, Judea and Idumea annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration,[126] capital at Caesarea, Quirinius became Legate (Governor) of Syria, conducted Census of Quirinius, opposed by Zealots (JA18, Luke 2:1-3, Acts 5:37)

- 7-26 Brief period of peace, relatively free of revolt and bloodshed in Iudaea & Galilee[127]

- 9 Pharisee leader Hillel the Elder dies, temporary rise of Shammai

- 14-37 Tiberius, Roman Emperor

- 18-36 Caiaphas, appointed High Priest of Herod's Temple by Prefect Valerius Gratus, deposed by Syrian Legate Lucius Vitellius

- 19 Jews, Jewish Proselytes, Astrologers, expelled from Rome[128]

- 26-36 Pontius Pilate, Prefect (governor) of Iudaea, recalled to Rome by Syrian Legate Vitellius on complaints of excess violence (JA18.4.2)

- 28 or 29 John the Baptist began his ministry in the "15th year of Tiberius" (Luke 3:1-2), saying: "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near" (Matt 3:1-2), a relative of Jesus (Luke 1:36), a Nazirite (Luke 1:15), baptized Jesus (Mark 1:4-11), later arrested and beheaded by Herod Antipas (Luke 3:19-20), it's possible that, according to Josephus' chronology, John was not killed until 36 (JA18.5.2)[129]

- 30 - Great Commission of Jesus to go and make disciples of all nations;[130] Pentecost, a day in which 3000 Jews from a variety of Mediterranean-basin nations are converted to faith in Jesus Christ.

- 34 - In Gaza, Philip baptizes a convert, an Ethiopian who was already a Jewish proselyte.

- 39 - Peter preaches to a Gentile audience in the house of Cornelius

- 37-41 Crisis under Caligula[131]

- 42 - Mark goes to Egypt [132]

- 44? Saint James the Great: According to ancient local tradition, on 2 January of the year AD 40, the Virgin Mary appeared to James on a Pilar on the bank of the Ebro River at Caesaraugusta, while he was preaching the Gospel in Spain. Following that apparition, St James returned to Judea, where he was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa I in the year 44 during a Passover (Nisan 15) (Acts 12:1-3).

- 44 Death of Herod Agrippa I (JA19.8.2, Acts 12:20-23)

- 44-46? Theudas beheaded by Procurator Cuspius Fadus for saying he would part the Jordan river (like Moses and the Red Sea or Joshua and the Jordan) (JA20.5.1, Acts 5:36-37 places it before the Census of Quirinius)

- 45-49? Mission of Barnabas and Paul, (Acts 13:1-14:28), to Cyprus, Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe (there they were called "gods ... in human form"), then return to Syrian Antioch. Map1

- 47? St. Thomas Christianity, now in several forms, is begun in India by Thomas.

- 47 - Paul (formerly known as Saul of Tarsus) begins his first missionary journey to modern-day Turkey.[133]

- 48-100 Herod Agrippa II appointed King of the Jews by Claudius, seventh and last of the Herodians

- 49 "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus,[134] he [Claudius] expelled them from Rome." (referenced in Acts 18:2)[135]

- 50 Passover riot in Jerusalem, 20-30,000 killed (JA20.5.3,JW2.12.1)

- 50 - Council of Jerusalem on admitting Gentiles into the Church[133]

- 50? Council of Jerusalem and the "Apostolic Decree", Acts 15:1-35, same as Galatians 2:1-10?, which is followed by the "Incident at Antioch"[136] at which Paul publicly accused Peter of "Judaizing" (2:11-21), see also Circumcision controversy in early Christianity

- 51 - Paul begins his second missionary journey, a trip that will take him through modern-day Turkey and on into Greece [137]

- 50-53? Paul's 2nd mission, (Acts 15:36-18:22), split with Barnabas, to Phrygia, Galatia, Macedonia, Philippi, Thessalonica, Berea, Athens, Corinth, "he had his hair cut off at Cenchrea because of a vow he had taken", then return to Antioch; 1 Thessalonians, Galatians written? Map2

- 51-52 or 52-53 proconsulship of Gallio according to an inscription, only fixed date in chronology of Paul[138]

- 52 Saint Thomas Christians of India

- 52 - Thomas arrives in India and founds church that subsequently becomes Indian Orthodox Church (and its various descendants) [139]

- 54 - Paul begins his third missionary journey [140]

- 53-57? Paul's 3rd mission, (Acts 18:23-22:30), to Galatia, Phrygia, Corinth, Ephesus, Macedonia, Greece, and Jerusalem where James the Just challenged him about rumor of teaching antinomianism (21:21), he addressed a crowd in their language (most likely Aramaic), Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Philippians written? Map3

- 55? "Egyptian Prophet" (allusion to Moses) and 30,000 unarmed Jews doing The Exodus reenactment massacred by Procurator Antonius Felix (JW2.13.5, JA20.8.6, Acts 21:38)

- 58? Paul arrested, accused of being a revolutionary, "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes", teaching resurrection of the dead, imprisoned in Caesarea (Acts 23-26)

- 59? Paul shipwrecked on Malta, there he was called a god (Acts 28:6)

- 60 - Paul sent to Rome under Roman guard, evangelizes on Malta after shipwreck [137]

- 60? Paul in Rome: greeted by many "brothers" (NRSV: "believers"), three days later called together the Jewish leaders, who hadn't received any word from Judea about him, but were curious about "this sect", which everywhere is spoken against; he tried to convince them from the "Law and Prophets", with partial success, said the Gentiles would listen and spent two years proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching the "Lord Jesus Christ" (Acts 28:15-31); Epistle to Philemon written?

- 62 James the Just stoned to death for law transgression by High Priest Ananus ben Artanus, popular opinion against act results in Ananus being deposed by new procurator Lucceius Albinus (JA20.9.1)

- 63-107? Simeon, 2nd Bishop of Jerusalem, crucified under Trajan

- 64-68 after July 18 Great Fire of Rome, Nero blamed and persecuted the Christians (or Chrestians[141]), possibly the earliest mention of Christians, by that name, in Rome, see also Tacitus on Jesus, Paul beheaded? (Col 1:24,Eph 3:13,2 Tim 4:6-8,1Clem 5:5-7), Peter crucified upside-down? (Jn 21:18,1 Pet 5:13,Tertullian's Prescription Against Heretics chapter XXXVI,Eusebius' Church History Book III chapter I), "...a vast multitude, were convicted, not so much of the crime of incendiarism as of hatred of the human race. And in their deaths they were made the subjects of sport; for they were wrapped in the hides of wild beasts and torn to pieces by dogs, or nailed to crosses, or set on fire, and when day declined, were burned to serve for nocturnal lights." (Annals (Tacitus) XV.44)

- 63 - Joseph of Arimathea travels to Glastonbury on the first Christian mission to Britain [142]

- 64/67(?)-76/79(?) Pope Linus succeeds Peter as Episcopus Romanus (Bishop of Rome)

- 65? Q document, a hypothetical Greek text thought by many critical scholars to have been used in writing of Matthew and Luke

- 66 - Thaddeus establishes the Christian church of Armenia [143]

- 66-73 Great Jewish Revolt: destruction of Herod's Temple, Qumran community destroyed, site of Dead Sea Scrolls found in 1947

- 68-107? Ignatius, third Bishop of Antioch, fed to the lions in the Roman Colosseum, advocated the Bishop (Eph 6:1, Mag 2:1,6:1,7:1,13:2, Tr 3:1, Smy 8:1,9:1), rejected Sabbath on Saturday in favor of The Lord's Day (Sunday). (Mag 9.1), rejected Judaizing (Mag 10.3), first recorded use of the term catholic (Smy 8:2).

- 69 - Andrew is crucified in Patras on the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece [144]

- 70(+/-10)? Gospel of Mark, written in Rome, by Peter's interpreter (1 Peter 5:13), original ending apparently lost, endings added c.400, see Mark 16

- 70? Signs Gospel written, hypothetical Greek text used in Gospel of John to prove Jesus is the Messiah

- 70-100? additional Pauline Epistles

- 70-200? Didache; Other Gospels: Unknown Berlin Gospel, Gospel of Peter, Gospel of Thomas, Oxyrhynchus Gospels, Egerton Gospel, Fayyum Fragment, Dialogue of the Saviour; Jewish Christian Gospels: Gospel of the Ebionites, Gospel of the Hebrews, Gospel of the Nazarenes

- 76/79(?)-88 Pope Anacletus first Greek Pope, who succeeds Linus as Episcopus Romanus (Bishop of Rome)

- 80 - First Christians reported in Tunisia and France [130]

- 80(+/-20)? Gospel of Matthew, theoretically based on Mark and Q, most popular in Early Christianity

- 80(+/-20)? Gospel of Luke, theoretically based on Mark and Q, also Acts of the Apostles by same author

- 88-101? Clement, fourth Bishop of Rome, wrote Letter of the Romans to the Corinthians (Apostolic Fathers)

- 90? Council of Jamnia of Judaism (disputed), Domitian applied the Fiscus Iudaicus tax even to those who merely "lived like Jews"[145]

- 90(+/-10)? 1 Peter

- 94 Testimonium Flavianum, disputed section of Jewish Antiquities by Josephus in Aramaic, translated to Koine Greek

- 95(+/-30)? Gospel of John and Epistles of John

- 95(+/-10)? Book of Revelation written, by John (son of Zebedee) and/or a disciple of his

- 100(+/-30)? Epistle of Barnabas (Apostolic Fathers)

- 100(+/-25)? Epistle of James

- 100(+/-10)? Epistle of Jude written, probably by doubting relative of Jesus (Mark 6,3), rejected by some early Christians due to its reference to apocryphal Book of Enoch (v14), Epistle to the Hebrews written

- 100 - First Christians are reported in Monaco, Algeria and Sri Lanka;[130] a missionary goes to Arbela, old sacred city of the Assyrians [146]

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- Christian martyrs

- Gospel harmony

- Jesuism

- New Testament view on Jesus' life

- Apostolic Age

- History of early Christianity

- Ante-Nicene Period

- Church Fathers

- Persecution of Christians in the New Testament

- Hellenistic Judaism

- List of events in early Christianity

- Development of the New Testament canon

- Christian monasticism

- Christianization

- East–West Schism

- History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

- Timeline of Christianity#Era of the Apostles

- Timeline of Christian missions#Era of the Apostles

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#Up to 312 AD

- Chronological list of saints in the 1st century

References

- ^ Hebrews 8:6

- ^ a b "Sermon on the Mount." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ McGrath, Alister E., Christianity: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing (2006), ISBN 1-4051-0899-1, Page 174: "In effect, they [Jewish Christians] seemed to regard Christianity as an affirmation of every aspect of contemporary Judaism, with the addition of one extra belief — that Jesus was the Messiah. Unless males were circumcised, they could not be saved (Acts 15:1)."

- ^ "The Canon Debate," McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 32, page 577, by James D. G. Dunn: "For Peter was probably in fact and effect the bridge-man... who did more than any other to hold together the diversity of first-century Christianity. James the brother of Jesus and Paul, the two other most prominent leading figures in first-century Christianity..." [Italics original]

- ^ a b c Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church ed. F.L. Lucas (Oxford) entry on Paul

- ^ R. E. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave (New York: Doubleday, Anchor Bible Reference Library, 1994), p. 964; S. J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Westminster Press, 1987, p. 78, 93, 105, 108; M.Grant, Jesus, An Historian's View of the Gospels (New York: Scribner's 1977) pp. 34–35, 78, 166, 200; P. Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews (Alfred A. Knopf, 1999) pp. 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew (Doubleday, 1991) vol. 1 pp. 68, 146, 199, 278, 386, and vol. 2 p. 726; G. Vermes, Jesus the Jew (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1973), p. 37.; P. L. Maier, In the Fullness of Time (Kregel, 1991) pp. 1, 99, 121, 171; N. T. Wright, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions (HarperCollins, 1998) pp. 32, 83, 100–102, 222; E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (Penguin Books, 1993); J. A. H. Moran Cruz and R. Gerberding, Medieval Worlds: An Introduction to European History (Houghton Mifflin Company 2004), pp. 44–45; J. D. Crossan, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant (HarperCollins, 1991) p. xi-xiii; L. T. Johnson, The Real Jesus (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1996), p. 123; Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus (Berlin: Deutsche Bibliothek, 1926), p. 159. The "life of Jesus" is a matter of academic debate. For a more complete analysis and bibliography, refer to the see also section.

- ^ on death by crucifixion, see L. T. Johnson, The Real Jesus (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1996); John P. Meier, "The Circle of the Twelve: Did It Exist during Jesus' Public Ministry?", in Journal of Biblical Literature 116 (1997) pp. 664–665

- ^ R. E. Brown, Death of the Messiah vol. 2 (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1994) pp. 1240–1241; J. A. T. Robinson, The Human Face of God (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1973) p. 131 and also J. Kremer, Die Osterevangelien-Geschichten um Geschichte (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1977) pp. 49–50; B. Ehrman, From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, lecture 4, "Oral and Written Traditions About Jesus" (The Teaching Company, 2003); M. J. Borg and N. T. Wright, The Meaning of Jesus (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1999), p. 12; G. Habermas, The Historical Jesus, (College Press, 1996) p. 128

- ^ M. Grant, Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels (New York: Scribner's 1977) p. 176; P. L. Maier, "The Empty Tomb as History" in Christianity Today (March 1975) p. 5; D. H. Van Daalen, The Real Resurrection (London: Collins, 1972), p. 41; Jakob Kremer, Die Osterevangelien — Geschichten um Geschichte (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1977), pp. 49–50; W. Craig, "The Disciples' Inspection of the Empty Tomb (Luke 24, 12.24; John 20, 1–10)", in John and the Synoptics, ed. A. Denaux, Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 101 (Louvain: University Press, 1992), pp. 614–619; W. Craig, "The Guard at the Tomb", in New Testament Studies 30 (1984) pp. 273–281; w. Craig, "The Historicity of the Empty Tomb of Jesus", in New Testament Studies 31 (1985): 39–67

- ^ R. H. Gundry, Soma in Biblical Theology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976); Johannes Weiss, Der erste Korintherbrief 9th ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1910) p. 345; W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism 2d ed (London: 1965) pp. 305–308; Ulrich Wilckens, Auferstehung (Stuttgart and Berlin: Kreuz Verlag, 1970) pp. 128–31; J. L. Smith, "Resurrection Faith Today", in TS 30 (1969) p. 406; J. Coppens, "La glorification céleste du Christ dans la théologie neotestamentaire et l'attente de Jésus", in Resurrexit ed. Édouard Dhanis (Rome: Editrice Libreria Vaticana, 1974) pp. 37–40; G. O'Collins, The Easter Jesus (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1973) p. 94; Clavier, "Breves remarques sur la notion de σωμα πνευματικον" in The background of the New Testament and Its Eschatology ed. W. D. Davies and D. Daube (Cambridge University Press, 1956) p. 361; J. E. Alsup, The Post-Resurrection Appearance Stories of the Gospel-Tradition (Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag, 1975)

- ^ L. T. Johnson, The Real Jesus (San Francisco, Harper San Francisco, 1996) p. 136; Gerd Ludemann, What Really Happened to Jesus? trans. J. Bowden (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1995) p. 8; N. T. Wright, "The New Unimproved Jesus", in Christianity Today (1993-09-13) p. 26; Gerd Lüdemann, What Really Happened to Jesus?, trans. John Bowden (Louisville, Kent.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1995), p. 80; James Orr, The Resurrection of Jesus (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1909) p. 39; Jindrich Mánek, "The Apostle Paul and the Empty Tomb", in NT 2 (1957) pp. 277–278; C. F. D. Moule, ed., "The Significance of the Message of the Resurrection for Faith in Jesus Christ", in SBT 8 (London: SCM, 1968); Jacob Kremer, "Zur Diskussion über "das leere Grab", in Resurrexit, ed. Edouard Dhanis (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vatica, 1974) pp. 143–144

- ^ "Christ's Life: Key Events". http://christianity.com/Christian%20Foundations/The%20Essentials/11542555/. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Loyola University Press, #651-655, pp. 170-171.

- ^ Matt 4:12-17

- ^ See Mark 15:42 and John 19:42. "Preparation Day" is normally Friday, but can also indicate whatever day is just before Passover. Nisan 14th seems indicated by John 19:14, Mark 14:2, and the "Gospel of Peter" but in Nisan 15th seems indicated by the Synoptic Gospels, see Meier

- ^ Franzen, Kirchegeschichte 20

- ^ a b Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), pp. 19–20

- ^ Schreck, The Essential Catholic Catechism (1999), p. 130

- ^ Brown (1993). Pg 10.

- ^ R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 51

- ^ a b Bargil Pixner, The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion, Biblical Archaeology Review 16.3 May/June 1990 [1]

- ^ 1:3–11, Luke 24:44-49, see also Luke-Acts

- ^ Acts 2

- ^ Acts 10

- ^ Acts 1:13-15

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Jerusalem (A.D. 71-1099): "During the first Christian centuries the church at this place was the centre of Christianity in Jerusalem, "Holy and glorious Sion, mother of all churches" (Intercession in "St. James' Liturgy", ed. Brightman, p. 54). Certainly no spot in Christendom can be more venerable than the place of the Last Supper, which became the first Christian church."

- ^ Acts 7:54-8:8

- ^ Acts 8:9-24

- ^ Acts 8:26-40

- ^ Acts 9:13-16

- ^ Acts 10

- ^ Acts 11:26

- ^ Acts 10, The Catholic Encyclopedia says of Cornelius: "The baptism of Cornelius is an important event in the history of the Early Church. The gates of the Church, within which thus far only those who were circumcised and observed the Law of Moses had been admitted, were now thrown open to the uncircumcised Gentiles without the obligation of submitting to the Jewish ceremonial laws."

- ^ Acts 15

- ^ Galatians 3

- ^ McGrath (2006). Pp 174-175.

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (2002), pp. 37–8, Chapter 1 The Early Christian Community subsection entitled "Rome", quote: "The 'synod' or, in Latin, 'council' (the modern distinction making a synod something less than a council was unknown in antiquity) became an indispensable way of keeping a common mind, and helped to keep maverick individuals from centrifugal tendencies. During the third century synodal government became so developed that synods used to meet not merely at times of crisis but on a regular basis every year, normally between Easter and Pentecost."

- ^ Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), p. 155, quote: "For all the scattered nature of the churches, a very large number of believers in apostolic times lived no more than a week or so's travel from one of the main hubs of the christian movement: Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome, Ephesus, Corinth or Philippi. Communities received regular visits from itinerant teachers and leaders.. This unity was focussed upon the essentials of belief in Jesus..

- ^ Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), pp. 169, 181

- ^ On the Creeds, see Oscar Cullmann, The Earliest Christian Confessions, trans. J. K. S. Reid (London: Lutterworth, 1949); on the Passion, see Rudolf Pesch, Das Markusevangelium, 2 vols., Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 2 (Freiburg: Herder, 1976–77), 2: 519–20

- ^ 1 Corinthians 15:3–4

- ^ Neufeld, The Earliest Christian Confessions (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964) p. 47; Reginald H. Fuller, The Formation of the Resurrection Narratives (New York: Macmillan, 1971) p. 10; Wolfhart Pannenberg, Jesus–God and Man translated Lewis Wilkins and Duane Pribe (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968) p. 90; Oscar Cullmann, The Earlychurch: Studies in Early Christian History and Theology, ed. A. J. B. Higgins (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966) p. 64; Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, translated James W. Leitch (Philadelphia: Fortress 1969) p. 251; Bultmann, Theology of the New Testament vol. 1 pp. 45, 80–82, 293; R. E. Brown, The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus (New York: Paulist Press, 1973) pp. 81, 92

- ^ see Wolfhart Pannenberg, Jesus–God and Man translated Lewis Wilkins and Duane Pribe (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968) p. 90; Oscar Cullmann, The Early church: Studies in Early Christian History and Theology, ed. A. J. B. Higgins (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966) p. 66–66; R. E. Brown, The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus (New York: Paulist Press, 1973) pp. 81; Thomas Sheehan, First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity (New York: Random House, 1986 pp. 110, 118; Ulrich Wilckens, Resurrection translated A. M. Stewart (Edinburgh: Saint Andrew, 1977) p. 2; Hans Grass, Ostergeschen und Osterberichte, Second Edition (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1962) p96; Grass favours the origin in Damascus.

- ^ Gerald O' Collins, What are They Saying About the Resurrection? (New York: Paulist Press, 1978) p. 112; on historical importance, cf. Hans von Campenhausen, "The Events of Easter and the Empty Tomb", in Tradition and Life in the Church (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968) p. 44; and also Archibald Hunter, Works and Words of Jesus (1973) p. 100

- ^ 1 John 4:2

- ^ Cullmann, Confessions p. 32

- ^ 2 Timothy 2:8

- ^ Bultmann, Theology of the New Testament vol 1, pp. 49, 81; Joachim Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus translated Norman Perrin (London: SCM Press, 1966) p. 102

- ^ Romans 1:3–4

- ^ Wolfhart Pannenberg, Jesus–God and Man translated Lewis Wilkins and Duane Pribe (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968) pp. 118, 283, 367; Neufeld, The Earliest Christian Confessions (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964) pp. 7, 50; C. H. Dodd, The Apostolic Preaching and its Developments (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1980) p. 14

- ^ 1 Timothy 3:16

- ^ Reginald H. Fuller, The Foundations of New Testament Christology (New York: Scriner's, 1965) pp. 214, 216, 227, 239; Joachim Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus translated Norman Perrin (London: SCM Press, 1966) p. 102; Neufeld, The Earliest Christian Confessions (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964) pp. 7, 9, 128

- ^ Franzen 24

- ^ Taylor (1993). Pg 224.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Jerusalem (A.D. 71-1099): "Epiphanius (d. 403) says..."; Epiphanius' Weights and Measures at tertullian.org.14: "For this Hadrian..."

- ^ Franzen 25

- ^ Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes Eamon Duffy, ch. 1

- ^ Ireneaus Against Heresies 3.3.2: the "...Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. ...The blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate."

- ^ Franzen 26

- ^ chapter 16

- ^ Pennington, p. 2

- ^ St-Paul-Outside-the-Walls homepage

- ^ Historians debate whether or not the Roman government distinguished between Christians and Jews prior to Nerva's modification of the Fiscus Judaicus in 96. From then on, practising Jews paid the tax, Christians did not. Wylen, Stephen M., The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction, Paulist Press (1995), ISBN 0-8091-3610-4, Pp 190-192.; Dunn, James D.G., Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, AD 70 to 135, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (1999), ISBN 0-8028-4498-7, Pp 33-34.; Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro & Gargola, Daniel J & Talbert, Richard John Alexander, The Romans: From Village to Empire, Oxford University Press (2004), ISBN 0-19-511875-8, p. 426.;

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Liturgy: Influence on Early Christian Liturgy

- ^ The traditional title is: The Divine Liturgy of James the Holy Apostle and Brother of the Lord; Ante-Nicene Fathers by Philip Schaff in the public domain, Schaff at ccel.org: Introductory Notice to the Early Liturgies: The Liturgy of St. James, the Liturgy of the Church of Jerusalem. Asseman, Zaccaria, Dr. Brett, Palmer, Trollope, and Neale, think that the main structure of this liturgy is the work of St. James, while they admit that it contains some evident interpolations. Leo Allatius, Bona, Bellarmine, Baronius, and some others, think that the whole is the genuine production of the apostle. Cave, Fabricius, Dupin, Le Nourry, Basnage, Tillemont, and many others, think that it is entirely destitute of any claim to an apostolic origin, and that it belongs to a much later age. [Editor's Note: Here the weight of authorities is clearly on this side.]"

- ^ Schaff, ibid

- ^ White (2004). Pg 127.

- ^ Ehrman (2005). Pg 187.

- ^ Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), p. 115

- ^ Greek Orthodox Christianity

- ^ A dictionary of Jewish-Christian relations, Dr. Edward Kessler, Neil Wenborn, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-82692-6, page 316: "Melito of Sardis first used 'Old Testament' to designate scripture. Tertullian, Eusebius, and others then used 'New Testament' for Christian texts viewed as inspired. By the fourth century 'New Testament' and 'Old Testament' became the common Christian terms for canonical materials."

- ^ The Canon Debate, McDonald & Sanders editors, chapter by Sundberg, page 72, adds further detail: "However, it was not until the time of Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) that the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures came to be called by the Latin term septuaginta. [70 rather than 72] In his City of God 18.42, while repeating the story of Aristeas with typical embellishments, Augustine adds the remark, "It is their translation that it has now become traditional to call the Septuagint" ...[Latin omitted]... Augustine thus indicates that this name for the Greek translation of the scriptures was a recent development. But he offers no clue as to which of the possible antecedents led to this development: Exod 24:1-8, Josephus [Antiquities 12.57, 12.86], or an elision. ...this name Septuagint appears to have been a fourth- to fifth-century development."

- ^ published by J. P. Audet in JTS 1950, v1, pp. 135–154, cited in The Council of Jamnia and the Old Testament Canon, Robert C. Newman, 1983.

- ^ The title Jesus Nave for the Book of Joshua is distinctly Christian.

- ^ The Canon Debate, McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, ISBN 1-56563-517-5, chapter 18 by Everett Ferguson titled Factors Leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon", page 310 quoting Tertullian: "Since Marcion separated the New Testament from the Old, he is necessarily subsequent to that which he separated, inasmuch as it was only in his power to separate what was previously united.", note 61 on page 308: "[Wolfram] Kinzig suggests that it was Marcion who usually called his Bible testamentum [Latin for testament]."

- ^ [[Mark Goodacre |Goodacre, Mark]] (2002). The Case Against Q:Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. Trinity Press International. ISBN 9781563383342. http://www.markgoodacre.org/Q/.

- ^ Against Heresies, 3.1.1

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh", Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p. 439, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh", p. 499, Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p. 439, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ Clontz, p. 516

- ^ Clontz, p. 587

- ^ Papias (c. 130) gives the perhaps earliest tradition of Mark's Apostolic connection: "This also the presbyter said: Mark, having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatsoever he remembered of the things said or done by Christ. For he neither heard the Lord nor followed him, but afterward, as I said, he followed Peter, who adapted his teaching to the needs of his hearers, but with no intention of giving a connected account of the Lord's discourses, so that Mark committed no error while he thus wrote some things as he remembered them. For he was careful of one thing, not to omit any of the thing which he had heard, and not to state any of them falsely" (cited by Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, 3.39.21ff.).

- ^ Irenaeus wrote about AD 180, "Luke, the attendant of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel which Paul had declared" (cited by Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, 5.8.3ff.).

- ^ calling himself John of Patmos

- ^ Eusebius Church History Book VI Ch 25 v14.

- ^ IVP Introduction to Hebrews by Ray Steadman

- ^ Robinson, Redating the New Testament, 1976, Wipf & Stock Publishers: ISBN 1-57910-527-0

- ^ G. Bromiley, ed (1982). [0-8028-3782-4 The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, "God"]. Fully Revised. Two: E-J. Eerdmans Publishing Comany. pp. 497–499. 0-8028-3782-4.

- ^ McGrath, Alister E., Christianity: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing (2006). ISBN 1-4051-0899-1. Page 174: "In effect, they Jewish Christians seemed to regard Christianity as an affirmation of every aspect of contemporary Judaism, with the addition of one extra belief — that Jesus was the Messiah. Unless males were circumcised, they could not be saved (Acts 15:1)."

- ^ E. Peterson, "Christianus" pp. 353–72

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Baptism: "According to rabbinical teachings, which dominated even during the existence of the Temple (Pes. viii. 8), Baptism, next to circumcision and sacrifice, was an absolutely necessary condition to be fulfilled by a proselyte to Judaism (Yeb. 46b, 47b; Ker. 9a; 'Ab. Zarah 57a; Shab. 135a; Yer. Kid. iii. 14, 64d). Circumcision, however, was much more important, and, like baptism, was called a "seal" (Schlatter, "Die Kirche Jerusalems," 1898, p. 70). But as circumcision was discarded by Christianity, and the sacrifices had ceased, Baptism remained the sole condition for initiation into religious life. The next ceremony, adopted shortly after the others, was the imposition of hands, which, it is known, was the usage of the Jews at the ordination of a rabbi. Anointing with oil, which at first also accompanied the act of Baptism, and was analogous to the anointment of priests among the Jews, was not a necessary condition."

- ^ Ignatius to the Magnesians chapter 9 at ccel.org

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Circumcision: In Apocryphal and Rabbinical Literature: "Contact with Grecian life, especially at the games of the arena [which involved nudity], made this distinction obnoxious to the Hellenists, or antinationalists; and the consequence was their attempt to appear like the Greeks by epispasm ("making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18; , Tosef., Shab. xv. 9; Yeb. 72a, b; Yer. Peah i. 16b; Yeb. viii. 9a). All the more did the law-observing Jews defy the edict of Antiochus Epiphanes prohibiting circumcision (I Macc. i. 48, 60; ii. 46); and the Jewish women showed their loyalty to the Law, even at the risk of their lives, by themselves circumcising their sons."; Hodges, Frederick, M. (2001). "The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme" (PDF). The Bulletin of the History of Medicine 75 (Fall 2001): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. http://www.cirp.org/library/history/hodges2/. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Cornelius: "The baptism of Cornelius is an important event in the history of the Early Church. The gates of the Church, within which thus far only those who were circumcised and observed the Law of Moses had been admitted, were now thrown open to the uncircumcised Gentiles without the obligation of submitting to the Jewish ceremonial laws."

- ^ "peri'ah", (Shab. xxx. 6)

- ^ Tabor (1998).

- ^ Esler (2004). Pp 157-159.

- ^ Dauphin (1993). Pp 235, 240-242.

- ^ http://www.stthoma.com/

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (2002), p. 37, Chapter 1 The Early Christian Community subsection entitled "Rome" by Henry Chadwick, quote: "In Acts 15 scripture recorded the apostles meeting in synod to reach a common policy about the Gentile mission."

- ^ McGrath, Alister E., Christianity: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing,(2006), ISBN 1-4051-0899-1, Page 174: "In effect, they [Jewish Christians] seemed to regard Christianity as an affirmation of every aspect of contemporary Judaism, with the addition of one extra belief — that Jesus was the Messiah. Unless males were circumcised, they could not be saved (Acts 15:1)."

- ^ Wylen (1995). Pg 190.

- ^ Berard (2006). Pp 112-113.

- ^ Wright (1992). Pp 164-165.

- ^ Wylen (1995). Pp 190-192.

- ^ Dunn (1999). Pp 33-34.

- ^ Boatwright (2004). Pg 426.

- ^ Theissen & Merz (1998), pp. 81-3

- ^ Franzen 29

- ^ a b Hitchcock, Geography of Religion (2004), p. 281, quote: "By the year 100, more than 40 Christian communities existed in cities around the Mediterranean, including two in North Africa, at Alexandria and Cyrene, and several in Italy."

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church (2004), p. 18, quote: "The story of how this tiny community of believers spread to many cities of the Roman Empire within less than a century is indeed a remarkable chapter in the history of humanity."

- ^ "Paul, St" Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005.

- ^ Acts 19, 18:1-18a, 16:12-15, 17:1-9

- ^ a b c Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ^ Apostolic Fathers, 2nd edition, 1992, page 25, Reception of the Letter

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Pope St. Clement I: The Epistle to the Corinthians: "The tone of authority with which the letter speaks is noteworthy, especially in the later part ... "It may, perhaps, seem strange", writes Bishop Lightfoot, "to describe this noble remonstrance as the first step towards papal domination. And yet undoubtedly this is the case."

- ^ Letter of Clement to the Corinthians, ch. 40

- ^ a b Draper, JA (2006), The Apostolic Fathers: the Didache, Expository Times, Vol.117, No.5, p.178

- ^ Aaron Milavec, p. vii