- Christianization of Bulgaria

-

Part of a series on Bulgarians

Culture of Bulgaria Literature · Music · Art

Cinema · Names · Cuisine

Dances · Costume · SportDiaspora United States · Canada

South America · Ukraine

Moldova · Spain

Italy · United Kingdom

Germany · France

Serbia · Romania

Hungary · Greek Macedonia

Albania · Turkey

People of Bulgarian descentReligions † Orthodox Christianity

(Bulgarian Orthodox Church)

small minority religions:

Muslim (by the Pomaks) · othersLanguages and dialects Bulgarian · Dialects The Christianization of Bulgaria was the process by which 9th-century medieval Bulgaria converted to Christianity. It was influenced by the khan's shifting political alliances with the kingdom of the East Franks and the Byzantine Empire, as well as his reception by the Pope of the Roman Catholic Church. Because of Bulgaria's strategic position, both Roman Catholic European kingdoms and the Byzantine Empire wanted Bulgaria's people to practice their respective religions and be aligned with them politically. Christianization was considered a means of integrating Slavs into the region. After some overtures to each side, the khan aligned with Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Through them, he achieved his goal of gaining an independent Bulgarian national church and having an archbishop appointed to head it.

Contents

Background

When Khan Boris began his reign in 852, the international situation was very complicated. The conflict with the Byzantine Empire for domination over the Slavic tribes in modern-day Macedonia and Thrace was still far from being resolved. In the middle Danube region, Bulgaria's interests crossed with those of the emerging kingdom of the East Franks and the principality of Great Moravia. It was about that period when Croatia emerged on the international scene, carrying its own ambitions and demands for territories in the region.

On a larger scale, the tensions between Constantinople and Rome were tightening. Both centres were competing to lead the Christianization that would integrate the Slavs in South and Central Europe. The Bulgarian Khanate and the Kingdom of the East Franks had established diplomatic relations as soon as the 20s and 30s of the 9th century. In 852, at the beginning of the reign of Khan Boris, a Bulgarian embassy was sent to Mainz to tell Louis II of the change in Pliska, the Bulgarian capital. Most probably the embassy also worked to renew the Bulgarian-German alliance.

Initial setbacks

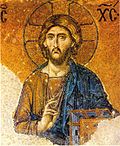

Part of a series on Eastern Christianity

History Orthodox Church History

Specific regions:

Byzantine Empire

Ecumenical council

Christianization of Bulgaria

Christianization of Kievan Rus'

East-West Schism

Asian Christianity

Coptic Egypt · UkraineTraditions Orthodox Church

Others:

Oriental Orthodoxy

Ethiopian Tewahedo Church

Coptic Church

Church of the East

Eastern Catholic Churches

Syriac ChristianityLiturgy and worship Sign of the cross

Divine Liturgy

Iconography

Asceticism

OmophorionTheology Hesychasm · Icon

Apophaticism

Filioque clause

Miaphysitism

Monophysitism

Diophysitism

Nestorianism

Theosis · Theoria

Phronema · Philokalia

Praxis · Theotokos

Hypostasis · Ousia

Essence vs. Energies

MetousiosisSome time later, Khan Boris concluded an alliance with the Great Moravian Knyaz Rastislav (846-870). The catalyst for this move was the King of the West Franks, Charles the Bald (840-877).[clarification needed] The German Kingdom responded by attacking Bulgaria. It defeated Bulgaria and forced Khan Boris to re-establish his alliance with the German king. This alliance was directed against Great Moravia, which was a Byzantine ally. The situation held great risk for the Bulgarian state.

Warfare started between Bulgaria and the Byzantines in 855-856. The Empire wanted to regain control over some fortresses on the Diagonal Road (Via Diagonalis or Via Militaris) that went from Constantinople, through Philippopolis (Plovdiv), to Naissus (Niš) and Singidunum (Belgrade). The Byzantine Empire was victorious and reconquered a number of cities, with Philippopolis being among them.[1]

Khan Boris' alliance with the Germans threatened Great Moravia, which sought help from Byzantium (862-863). This was at the same time when a Byzantine mission to Great Moravia was taking place. Cyril and his brother Methodius) intended to draw Great Moravia closer to Constantinople circle and strengthen the Byzantine (Orthodox Christian) influence there.

Khan Boris was more interested that the two brothers, Cyril and Methodius, brought the first Slavonic alphabet to Knyaz Rostislav. Bulgaria wanted to implement a Slavonic alphabet as well, as a means to stop the cultural influence of its enemy, the Byzantine Empire.

In the last months of 863, the Byzantines attacked Bulgaria again. The most probable reason was that rulers learned of Boris' telling the German king that he wanted to accept Christianity. Byzantium had to forestall Bulgaria from taking up Roman Catholicism. It considered a Catholic Bulgaria in the hinterland of Constantinople as a threat to the Byzantine Empire's immediate interests.

Byzantine demand

Byzantium did not demand territories but the conversion to Eastern Christianity of Bulgarian representatives and leaders, followed by conversion by the rest of the Bulgarian people. Such an demand would be unacceptable in other circumstances.

The two sides concluded a "deep peace" for a 30-year period. In the late autumn of 863, a mission from the Patriarch of Constantinople came to Pliska and converted the khan, his family and high-ranking dignitaries. They were all baptized as Christians.

Reasons for the Christianization

Following the conquests of Khan Krum of Bulgaria at the beginning of the 9th century, Bulgaria became an important regional power in Southeastern Europe. Its future development was connected with the Byzantine and East Frankish empires. Since both of these states were Christian, pagan Bulgaria remained more or less in isolation, unable to interact on even grounds, neither culturally nor religiously.

After the conversion of the Saxons, most of Europe was Christian. The preservation of paganism among the Bulgars and the Slavs (the two ethnic groups that formed the Bulgarian people) brought another disadvantage — the two ethnic groups' unification was hampered by their different religious beliefs. Lastly, Christianity had its roots in the Bulgarian lands prior to the formation of the Bulgarian state.

Reaction

Louis, King of East Francia, was not satisfied with Boris's plan to convert to Orthodox Christianity, as he had hoped to have Bulgaria be a Catholic state. He did not carry his fears to open conflict.

As Byzantine missions converted the Bulgarians, their forces encouraged the people to destroy the pagan holy places. Conservative Bulgarian aristocratic circles opposed such destruction, as they had led the spiritual rituals. In 865, malcontents from all ten administrative regions (komitats) revolted against Boris (now titled Knyaz), accusing him of giving them "a bad law". The rebels moved toward the capital intending to capture and kill the knyaz, and to restore the old religion.

All that is known is that Knyaz Boris gathered people loyal to him and suppressed the revolt. He ordered the execution of 52 [1] boyars who were leaders in the revolt, "along with their whole families". The commonfolk who "wished to do penance" were allowed to go without harm.

Until the end of his life, Knyaz Boris was haunted by guilt about the harshness of his measures and the moral price of his decision in 865. In his later correspondence with Pope Nicholas I, the knyaz asked whether his actions had crossed the borders of Christian humility. The pope answered:

“ ... You have sinned rather because of zeal and lack of knowledge, than because of other vice. You receive forgiveness and grace and the benevolence of Christ, since penance has followed on your behalf. ” Critics may disagree with the Pope's assessment. Historians believe the knyaz executed almost half the Bulgarian aristocracy to end the religious and political conflict. His aristocratic opponents had feared that the Byzantine Empire would spread its influence through Christianity and destroy Bulgaria. At this time during the Middle Ages, Bulgarians considered "Christians" as equivalent to their traditional competitors the "Byzantines", or "Greeks", as they were most often called. Many Bulgarians thought that along with Christianity, they would be forced to accept the Byzantine way of life and morals.

Choice between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism

Knyaz Boris realized that the Christianization of his subjects would result in greater Byzantine influence. The liturgy was performed in the Greek language, and the newly established Bulgarian Church was subordinate to the Church of Constantinople. The revolt against the new religion prompted the Knyaz to ask Constantinople to allow the Bulgarian Church independent status.

Prior to the middle of the 9th century, in the practice of the formally united Church, there were no precedents for creating national churches among newly converted peoples. Bulgaria created this precedent and set the example for others to follow.

When Constantinople refused to grant the Bulgarian Church independence, Knyaz Boris turned to the Pope. At the end of August 866, a Bulgarian mission led by the kavhan Peter arrived in Rome, carrying a list of 115 questions from Knyaz Boris. These had to do with the Christian way of life of the newly converted Bulgarians and the potential organization of a future Bulgarian Church under Rome's jurisdiction. On 13 November 866, the Bulgarian knyaz received the Pope's 106 answers. Formosa from Portua and Paul of Populon led the Pope's mission. At the same time, the Pope sent other emissaries to Constantinople.

When the Roman clerical mission arrived, Knyaz was sufficiently satisfied with Rome's response that he ordered the Byzantine mission to leave Bulgaria. This was viewed as an official change of Bulgarian orientation from Constantinople to Rome. Seeing Rome's emissaries there, the German mission also left Bulgaria, satisfied that the people would become Roman Catholic.

Emperor Michael III was displeased by Bulgaria's banishment of Byzantium's clergy. In a letter to Knyaz Boris, the Byzantine emperor expressed his disapproval of Bulgaria's religious reorientation by using offensive language against the Roman Church. The old rivalry between the two branches of Christianity burned with new power. In less than two years, Bulgaria's name became widely known in Western Europe.

In Constantinople, people nervously watched the events taking place in Bulgaria. They believed a pro-Roman Bulgaria threatened Constantinople's immediate interests. A religious council was held in the summer of 867 in the Byzantine capital, during which clerics criticized the Roman Church's actions of recruiting Bulgaria. Pope Nicholas I was anathematized.

Without losing time, Knyaz Boris asked the Pope to appoint Formosa of Portua as Bulgarian Archbishop. The Pope refused. Nicholas I likely had some personal reasons for his decision, because the official response, that Formosa already had an eparchy, was untrue.

The Pope ordered new leaders, Dominic of Trivena and Grimwald of Polimarthia, of a mission to be sent to Bugaria. Soon after, Pope Nicolas I died. His successor, Pope Adrian II (867-872), also failed to respond to Knyaz Boris' request for appointment of a Bulgarian archbishop.

The Knyaz proposed another candidate for Bulgarian archbishop, but the Pope refused. Instead, he suggested a cleric named Silvester. The man was so low in the hierarchy that he was not authorized to carry out liturgy alone. After he had a three-day stay in Pliska, the Bulgarians sent Silverster back to Rome, accompanied by emissaries carrying a letter of complaint by Knyaz Boris. The Knyaz perceived Rome's refusals of his request and delays as an insult and a sign of the Pope's unwillingness to coordinate selection with him of a Bulgarian archbishop.

As a result, Knyaz Boris began negotiations again with Constantinople, where he expected more cooperation than shown in the past. But, on 23 September 867, Emperor Michael III was killed by his close acquaintance Basil, who started the Dynasty of the Macedonians that ruled the Empire until 1057. Patriarch Photius was replaced by his ideological rival Ignatius (847-858; 867-877). Ignatius brought about a change in the relations with the Roman Church.

The new rulers of the Byzantine Empire quickly lessened tensions between Constantinople and Rome. Pope Adrian II needed the help of Basil I against the Arabs' attacks in Southern Italy. At the same time, Byzantium anticipated the Pope's support for Patriarch Ignatius.

Result

As a result of the leaders' agreements, a Church Council was held in Constantinople. After the end of the official conferences, on 28 February 870 Bulgarian emissaries arrived in Constantinople, sent by the Knyaz and led by the Ichirguboil (the first councilor of the Knyaz) Stasis, the Kan-Bogatur (high-ranking aristocrat) Sondoke, the Kan-Tarkan (high-ranking military commander) among others.

Few people suspected the real purpose of these emissaries. On 4 March Emperor Basil I closed the Council with a celebration at the Emperor's palace. In attendance was the Bulgarian Kavkan (roughly a vicekhan or viceknyaz) Peter. After he greeted the representatives of the Roman and Byzantine Churches (the Roman being first), Kavkan Peter asked under whose jurisdiction the Bulgarian Church should fall. The Roman representatives were not prepared to discuss this matter.

There appeared to have been a secret agreement between the Byzantine Patriarch, the Emperor and the Bulgarian emissaries. The Orthodox fathers immediately asked the Bulgarians whose clergy they had found when they came to the lands which they now ruled. They answered "Greek". The Orthodox fathers declared that the right to oversee the Bulgarian Church belonged only to the Constantinople Mother Church, which had held jurisdiction on these lands in the past.

The protests of the Pope's emissaries were not taken into account. With the approval of the Knyaz and the Fathers of the Council, the Bulgarian Church was declared an Archbishopric. The Archbishop was to be elected among the bishops with the approval of the Knyaz.

The creation of an independent Bulgarian Archbishopric was unprecedented in the practice of the Churches. Usually, independent churches were those founded by apostles or apostles' students. For a long period, Rome had been challenging Constantinople's claim of equality to Rome, on the grounds that the Church of Constantinople had not been founded by an apostle of Christ.

Just six years after his conversion, the Orthodox Church granted Knyaz Boris a national independent church and a high-ranking supreme representative (the Archbishop). In the next 10 years, Pope Adrian II and his successors made desperate attempts to regain their influence in Bulgaria and to persuade Knyaz Boris to leave Constantinople's sphere.

The foundations of the Bulgarian national Church had been set. The next stage was the implementation of the Cyrillic alphabet and the Old Bulgarian language, as the official language of the Bulgarian Church and State in 893 AD during the Council of Preslav. Such nationalization of the church and liturgy was exceptional and not at all part of the practice of other European Christians.

See also

- Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Cyrillic alphabet

- Boris I of Bulgaria

- Glagolitic alphabet

- Ballshi inscription

Notes

- ^ Gjuzelev, p. 130

References

- Gjuzelev, V., (1988) Medieval Bulgaria, Byzantine Empire, Black Sea, Venice, Genoa (Centre culturel du monde byzantin). Verlag Baier.

Topics on the Bulgarian Empire State Military Culture OriginStates- First Bulgarian Empire (681-1018)

- Second Bulgarian Empire (1185-1396)

De facto independent Bulgarian states from the Second Empire

- Tsardom of Vidin (1356-1396)

- Principality of Karvuna (1320-1395)

Administration- Medieval Bulgarian aristocracy

- Capitals: Pliska (681-893) • Preslav (893-972) • Skopie (972-992) • Ohrid (992-1018) • Tarnovo (1185-1393) • Nikopol (1393-1395) • Vidin (1393-1396)

Important rulersFirst Bulgarian Empire

Asparukh • Tervel • Krum • Omurtag • Boris I • Simeon I the Great • Peter I • Samuil

Second Bulgarian Empire

Ivan Asen I • Kaloyan • Ivan Asen II • Constantine Tikh Asen • Michael Shishman • Ivan Alexander

Conflicts

Conflicts- Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars

- Bulgarian-Croatian Wars

- Bulgarian-Hungarian Wars

- Bulgarian-Latin Wars

- Bulgarian-Ottoman Wars

- Bulgarian-Serbian Wars

Major battlesFirst Bulgarian Empire

Battle of Ongal • Siege of Constantinople • Battle of Marcellae • Battle of Pliska • Battle of Southern Buh • Battle of Acheloos • Battle of the Gates of Trajan • Battle of Kleidion

Second Bulgarian Empire

Battle of Tryavna • Battle of Adrianople • Battle of Klokotnitsa • Battle of Skafida • Battle of Velbazhd • Battle of Rusokastro • Battle of Chernomen • Siege of Tarnovo

Major uprisings- Uprising of Peter Delyan

- Uprising of Georgi Voiteh

- Uprising of Asen and Peter

- Uprising of Ivailo

- Uprising of Konstantin and Fruzhin

Literature- Medieval Bulgarian literature

- Glagolitic alphabet

- Early Cyrillic alphabet

- Cyrillic alphabet

- Old Church Slavonic

- Preslav Literary School

- Ohrid Literary School

- Medieval Bulgarian royal charters

Prominent writers and scholars: Naum of Preslav • Clement of Ohrid • Chernorizets Hrabar • Constantine of Preslav • John Exarch • Evtimiy of Tarnovo • Gregory Tsamblak

Art and ArchitectureFamous examples: Madara Rider • Great Basilica of Pliska • Round Church in Preslav • Holy Forty Martyrs Church in Tarnovo • Boyana Church • Tsarevets • Baba Vida

Religion- Tengriism

- Slavic religion

- Christianization of Bulgaria

- Orthodox Church

- Bulgarian Orthodox Patriarchate

- Bulgarian Orthodox Archbishopric

- Roman Catholicism

- Bogomilism

Economy- Medieval Bulgarian economy

- Medieval Bulgarian coinage

Categories:- Bulgarian people

- History of Bulgaria

- Bulgarian Empire

- Christianity in medieval Macedonia

- Medieval Thrace

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.