- Christianity in the 4th century

-

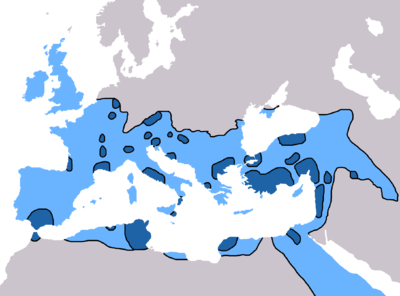

Christianity in the 4th century was dominated by Constantine the Great, and the First Council of Nicea of 325, which was the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787) and the attempt to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christendom as the State church of the Roman Empire, which formally failed with the East–West Schism of 1054.

Christian persecutions

-

With Christianity the dominant faith in some urban centers. Christians accounted for approximately 10% of the Roman population by 300, according to some estimates.[5] Roman Emperor Diocletian launched the bloodiest campaign against Christians that the empire had witnessed. The persecution ended in 311 with the death of Diocletian. The persecution ultimately had not turned the tide on the growth of the religion.[6] Christians had already organized to the point of establishing hierarchies of bishops, see for example Metropolitan bishop. In 301 CE the Kingdom of Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity (see Armenian Apostolic Church). The Romans would follow in 380.Major communions of

the 4th and 5th centuriesCommunion Primary centers Roman imperial

churchRome,

ConstantinopleChurch of the East Syria, Sassanid

(Persia) Empire[1]Oriental Orthodox or

Non-ChalcedonianArmenia, Syria,

Egypt[2]Donatist Church North Africa[3] Gothic Arian Church Gothic tribes[4]

Christianity as a legal religion in the Roman Empire

Under Galerius

In April 311, Galerius, who had previously been one of the leading figures in the persecutions, issued an edict permitting the practice of the Christian religion under his rule.[7] During the years 313 to the year 380, Christianity enjoyed the status of being a 'legal religion' within the Roman Empire. During these years, it had not yet become the sole authorized state religion, however during this period it gradually but continually gained in prominence and stature within Roman society. After halting the persecutions of the Christians, Galerius reigned for another 2 years. He was then succeeded by an emperor with distinctively pro Christian leanings, Constantine the Great.

Christianity legalized by Constantine I

Christian sources record that Constantine experienced a dramatic event in 312 at the Battle of Milvian Bridge, after which Constantine would claim the emperorship in the West. According to these sources, Constantine looked up to the sun before the battle and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek words "ΕΝ ΤΟΥΤΩ ΝΙΚΑ" ("by this, conquer!", often rendered in the Latin "in hoc signo vinces"); Constantine commanded his troops to adorn their shields with a Christian symbol (the Chi-Ro), and thereafter they were victorious.[8][9] How much Christianity Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern; most influential people in the empire, especially high military officials, were still pagan, and Constantine's rule exhibited at least a willingness to appease these factions. The Roman coins minted up to eight years subsequent to the battle still bore the images of Roman gods.[8] Nonetheless, the accession of Constantine was a turning point for the Christian Church. After his victory, Constantine supported the Church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges (e.g., exemption from certain taxes) to clergy, promoted Christians to high ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the Great Persecution of Diocletian.[10] Between 324 and 330, Constantine built, virtually from scratch, a new imperial capital at Byzantium on the Bosphorus (it came to be named for him: Constantinople)–the city employed overtly Christian architecture, contained churches within the city walls (unlike "old" Rome), and had no pagan temples.[11]

Constantine I's formative influence in the 'Romanization' of Christianity

Under the influence of Constantine I, the Christian movement gradually underwent its major transformation from a previously underground and even criminal movement into an officially sanctioned religion of 'first rank' within the Roman Empire. Constantine I chose to take a lead role in much of this transformation. In 316 he acted as a judge in a North African dispute concerning the Donatist controversy. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council (the Council of Jerusalem was the first recorded Christian council but rarely is it considered ecumenical), to deal mostly with the Arian controversy, but which also issued the Nicene Creed, which among other things professed a belief in One Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, the start of Christendom. He considered himself to be a Christian, but Constantine chose to wait until his deathbed to be baptized, a common practice at the time.

Constantine himself began to utilize Christian symbols early in his reign but still encouraged traditional Roman religious practices including sun worship. In AD 313 Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan reaffirming the tolerance of Christians and returning previously confiscated property to the churches. In 330 he established the city of Constantinople as the new capital of the Roman Empire. The city would gradually come to be seen as the center of the Christian world.[12]

The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the Christian Emperor in the Church. Emperors considered themselves responsible to God for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus they had a duty of maintain orthodoxy.[13] The emperor did not decide doctrine – that was the responsibility of the bishops – rather his role was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity.[14] The emperor ensured that God was properly worshiped in his empire; what proper worship consisted of was the responsibility of the church. This precedent would continue until certain emperors of the 5th and 6th centuries sought to alter doctrine by imperial edict without recourse to councils, though even after this Constantine's precedent generally remained the norm.[15]

Christianity under successive emperors

Constantine's sons banned pagan State religious sacrifices in 341, but did not close the temples. Although all State temples in all cities were ordered shut in 356, there is evidence that traditional sacrifices continued. When Gratian declined the position and title of Pontifex Maximus, his act effectively brought an end to the state religion due to the positions authority and ties within the Imperial administration. This ended state official practices but not the private religious practices, and consequently the temples remained open.

There was not a total unity of Christianity however, and Constantius II was an Arian who kept Arian bishops at his court and installed them in various sees, expelling the orthodox bishops.

Christianity temporarily relegated to secondary religion of the Empire

Constantius's successor, Julian, known in the Christian world as Julian the Apostate, was a philosopher who upon becoming emperor renounced Christianity and embraced a Neo-platonic and mystical form of paganism shocking the Christian establishment. While not actually re-criminilizing Christianity, he became intent on re-establishing the prestige of the old pagan beliefs and practices. He modified these practices to resemble Christian traditions such as the episcopal structure and public charity (hitherto unknown in Roman paganism). Julian eliminated most of the privileges and prestige previously afforded to the Christian Church. His reforms attempted to create a form of religious heterogeneity by, among other things, reopening pagan temples, accepting Christian bishops previously exiled as heretics, promoting Judaism, and returning Church lands to their original owners. However, Julian's short reign ended when he died while campaigning in the East. Christianity came to dominance during the reign of Julian's successors, Jovian, Valentinian I, and Valens (the last Eastern Arian Christian Emperor).

Nicaea Christianity becomes the state religion of the Roman Empire

Over the course of the 4th century the Christian body became consumed by debates surrounding orthodoxy, i.e. which religious doctrines are the correct ones. By the early 4th century a group in North Africa, later called Donatists, who believed in a very rigid interpretation of Christianity that excluded many who had abandoned the faith during the Diocletian persecutions, created a crisis in the western Empire.[16] A Church synod, or council, was called in Rome in 313 followed by another in Arles in 314. The latter was presided over by Constantine while he was still a junior emperor (see Tetrarchy). The councils ruled that the Donatist faith was heresy and, when the Donatists refused to recant, Constantine launched the first campaign of persecution by Christians against Christians. This was only the beginning of imperial involvement in the Christian theology.

Christian scholars within the Empire were increasingly embroiled in debates regarding Christology (on the nature of the Christ). Opinions were widespread ranging from the belief that Jesus was entirely mortal to the belief that was an Incarnation of God that had taken human form. The most persistent debate was that between the homoousian, or Athanasian, view (the Father and the Son are one and the same, eternal) and the homoiousian, or Arian, view (the Father and the Son are separate, but both divine). This controversy led to Constantine's calling a council meeting at Nicaea in 325 which voted for the Athanasian view.[17]

Christological debates raged throughout the 4th century with emperors becoming ever more involved with the Church and the Church becoming ever more divided.[18] The Council of Nicaea in 325 supported the Athanasian view. The Council of Rimini in 359 supported the Arian view. The Council of Constantinople in 360 supported a compromise that allowed for both views. The Council of Constantinople in 381 re-asserted the Athanasian view and rejected the Arian view. Emperor Constantine was of divided opinions (even as to whether he was Christian) but he largely backed the Athanasian faction (though he was baptized on his death bed by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia). His successor Constantius II supported a Semi-Arian position. Emperor Julian favored a return the traditional (pagan) Roman/Greek religion but this trend was quickly quashed by his successor Jovian, a supporter of the Athanasian faction.

In 380 Emperor Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica, which established Christianity as the official state religion, specifically the faith established by the Council of Nicaea in 325:[19] Prior to this date, such Emperors as Constantius II (337-361) and Valens (364-378) had favored Arian or Semi-Arian forms of Christianity. Theodosius called the Council of Constantinople in 381 to further refine the definition of orthodoxy. In 391 Theodosius closed all of the pagan (non-Christian and non-Jewish) temples and formally forbade pagan worship. These adhering state churches can be seen as effectively a department of the Roman state. All other Christian sects were explicitly declared heretical and illegal. In 385, came the first capital punishment of a heretic, namely Priscillian of Ávila.[20][21]

Ecumenical Councils of the 4th century

Main article: First seven Ecumenical CouncilsBeginning with those called by Constantine, the most significant role of the councils of the 4th and 5th centuries was to define orthodoxy within the Empire. These were mostly concerned with Christological disputes. The two Councils of Nicaea (325, 382) condemned Arian teachings as heresy and produced a creed (see Nicene Creed). The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). Perhaps the most significant council was the Council of Chalcedon that affirmed that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union. This was based largely on Pope Leo the Great's Tome. Thus, it condemned Monophysitism and would be influential in refuting Monothelitism. However, not all denominations accepted all the councils, for example Nestorianism and the Assyrian Church of the East split over the Council of Ephesus of 431, Oriental Orthodoxy split over the Council of Chalcedon of 451, Pope Sergius I rejected the Quinisext Council of 692 (see also Pentarchy), and the Fourth Council of Constantinople of 869–870 and 879–880 is disputed by Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

These Councils were:

- First Council of Nicaea (325)

- First Council of Constantinople (381)

These two councils were a part of what would later be called the first seven Ecumenical Councils, from the First Council of Nicaea (325) to the Second Council of Nicaea (787).

- The first of the Seven Ecumenical Councils was that convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine at Nicaea in 325, condemning the view of Arius that the Son is a created being inferior to the Father.

- The Second Ecumenical Council was held at Constantinople in 381, defining the nature of the Holy Spirit against those asserting His inequality with the other persons of the Trinity. Under Theodosius I this council marks the end of the Arian conflict in the Eastern Roman Empire..

This era begins with the First Council of Nicaea, which enunciated the Nicene Creed that in its original form and as modified by the First Council of Constantinople of 381 was seen as the touchstone of orthodoxy on the doctrine of the Trinity. The Council of Nicaea in 325 most of the other councils of the 4th century dealt with the debate between the Athanasian and Arian christological viewpoints. The Council of Nicaea backed the Athanasian view whereas the Council of Rimini backed the Arian view (Rimini actually had more attendees than Nicaea).[22] Ultimately the Athanasian view with its formulation of the Holy Trinity became the official state religion. At this point, though the emperors had already ceased to reside habitually at Rome, the church in that city was seen as the first church among churches[23] In 330 Constantine built his "New Rome", which became known as Constantinople, in the East. And all the seven councils were held in the East, specifically in Anatolia or Constantinople which is just across the Bosphorus. In 410 the Visigoths sacked Rome, but then withdrew. In 568 the Lombards invaded Italy and established a Kingdom of Italy that lasted until 774, for nearly all of which period (until 751) Rome was governed by the Exarchate of Ravenna, representing the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople.

Confronting Arianism

The first ecumenical council was convened to address again the divinity of Christ (see Paul of Samosata and the Synods of Antioch) through the teachings of Arius, an Egyptian presbyter from Alexandria. Arius taught that Jesus Christ was divine and was sent to earth for the salvation of mankind but that Jesus Christ was not equal to the Father (infinite, primordial origin) and to the Holy Spirit (giver of life). Under Arianism, Christ was instead not consubstantial with God the Father.[24] Since both the Father and the Son under Arius were made of "like" essence or being (see homoiousia) but not of the same essence or being (see homoousia).[25] Much of the distinction between the differing factions was over the phrasing that Christ expressed in the New Testament to express submission to God the Father.[26] This Ecumenical council declared that Jesus Christ was a distinct being of God in existence or reality (hypostasis), which the Latin fathers translated as persona. Jesus was God in essence, being and or nature (ousia), the Latin fathers translated as substantia.

When Emperor Constantine I was baptized, the baptism was performed by an Arian bishop and relative, Eusebius of Nicomedia. Also the charges of Christian corruption by Constantine (see the Constantinian shift) ignore the fact that Constantine deposed Athanasius of Alexandria and later restored Arius, who had been branded a heresiarch by the Nicene Council.[27][28][29][30][31]

Constantine I was succeeded by two Arian Emperors Constantius II and Valens and a Pagan Emperor in Julian the Apostate. Even after Constantine I, Orthodox Christians remained persecuted but to a much lesser degree than when Christianity was an illegal community (see Persecution of early Christians by the Romans, Shapur II and Basil of Ancyra). It was not until Emperor Gratian that an Orthodox Emperor was again put on the throne in the East and West seats of Emperor (Jovian was only Emperor for 6 months). Emperor Gratian established the Spaniard Theodosius I as his co-emperor in Byzantium. It was not until the co-reigns of Gratian and Theodosius that Arianism was effectively wiped out among the ruling class and elite of the Eastern Empire. Theodosius' wife St Flacilla was instrumental in his campaign to end Arianism. This later culminated into the killing of some 300,000 Orthodox Christians at the hands of Arians in Milan in 538AD.[32]

First Council of Nicaea

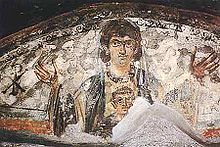

Emperor Constantine presents a representation of the city of Constantinople as tribute to an enthroned Mary and baby Jesus in this church mosaic. St Sophia, c. 1000).

Emperor Constantine presents a representation of the city of Constantinople as tribute to an enthroned Mary and baby Jesus in this church mosaic. St Sophia, c. 1000).

The First Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea in Bithynia (in present-day Turkey), convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325, was the first ecumenical[33] conference of bishops of the Catholic Church (Catholic as in 'universal', not just Roman) and most significantly resulted in the first declaration of a uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. With the creation of the creed, a precedent was established for subsequent 'general (ecumenical) councils of Bishops' (Synods) to create statements of belief and canons of doctrinal orthodoxy— the intent being to define unity of beliefs for the whole of Christendom.

The purpose of the council was to resolve disagreements in the Church of Alexandria over the nature of Jesus in relationship to the Father; in particular, whether Jesus was of the same substance as God the Father or merely of similar substance. Alexander of Alexandria and Athanasius took the first position; the popular presbyter Arius, from whom the term Arian controversy comes, took the second. The council decided against the Arians overwhelmingly (of the estimated 250–318 attendees, all but 2 voted against Arius). Another result of the council was an agreement on the date of the Christian Passover (Pascha in Greek; Easter in modern English), the most important feast of the ecclesiastical calendar. The council decided in favour of celebrating the resurrection on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, independently of the Bible's Hebrew Calendar (see also Quartodecimanism), and authorized the Bishop of Alexandria (presumably using the Alexandrian calendar) to announce annually the exact date to his fellow bishops.

The Council of Nicaea was historically significant because it was the first effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom.[34] "It was the first occasion for the development of technical Christology."[34] Further, "Constantine in convoking and presiding over the council signaled a measure of imperial control over the church."[34] With the creation of the Nicene Creed, a precedent was established for subsequent general councils to create a statement of belief and canons which were intended to become guidelines for doctrinal orthodoxy and a source of unity for the whole of Christendom – a momentous event in the history of the Church and subsequent history of Europe.

Emperor Constantine convened this council to settle a controversial issue, the relation between Jesus Christ and God the Father. The Emperor wanted to establish universal agreement on it. Representatives came from across the Empire, subsidized by the Emperor. Previous to this council, the bishops would hold local councils, such as the Council of Jerusalem, but there had been no universal, or ecumenical, council.

The council drew up a creed, the original Nicene Creed, which received nearly unanimous support. The council's description of "God's only-begotten Son", Jesus Christ, as of the same substance with God the Father became a touchstone of Christian Trinitarianism. The council also addressed the issue of dating Easter (see Quartodecimanism and Easter controversy), recognised the right of the see of Alexandria to jurisdiction outside of its own province (by analogy with the jurisdiction exercised by Rome) and the prerogatives of the churches in Antioch and the other provinces[35] and approved the custom by which Jerusalem was honoured, but without the metropolitan dignity.[36]

The Council was opposed by the Arians, and Constantine tried to reconcile Arius, after whom Arianism is named, with the Church. Even when Arius died in 336, one year before the death of Constantine, the controversy continued, with various separate groups espousing Arian sympathies in one way or another.[37] In 359, a double council of Eastern and Western bishops affirmed a formula stating that the Father and the Son were similar in accord with the scriptures, the crowning victory for Arianism.[37] The opponents of Arianism rallied, but in the First Council of Constantinople in 381 marked the final victory of Nicene orthodoxy within the Empire, though Arianism had by then spread to the Germanic tribes, among whom it gradually disappeared after the conversion of the Franks to Catholicism in 496.[37]

Nicene Creed

Icon depicting Emperor Constantine, center, accompanied by the Church Fathers of the 325 First Council of Nicaea, holding the Nicene Creed in its 381 form.

Icon depicting Emperor Constantine, center, accompanied by the Church Fathers of the 325 First Council of Nicaea, holding the Nicene Creed in its 381 form.

Each phrase in the Nicene Creed, which was hammered out at the Council of Nicaea, addresses some aspect that had been under passionate discussion and closes the books on the argument, with the weight of the agreement of the over 300 bishops in attendance. [Constantine had invited all 1800 bishops of the Christian church (about 1000 in the east and 800 in the west). The number of participating bishops cannot be accurately stated; Socrates Scholasticus and Epiphanius of Salamis counted 318; Eusebius of Caesarea, only 250.] In spite of the agreement reached at the council of 325 the Arians who had been defeated dominated most of the church for the greater part of the 4th century, often with the aid of Roman emperors who favored them. In the East, the successful party of Cyril cast out Nestorius and his followers as heretics and collected and burned his writings.

First Council of Constantinople (381)

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed as used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodox churches, but, except when Greek is used, with two additional Latin phrases ("Deum de Deo" and "Filioque") in the West. The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions.[38] This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.[39]

The council also condemned Apollinarism,[40] the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ.[41] It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.[40]

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was accepted as ecumenical in the West.[40]

The First Council of Constantinople (AD 381) suggested strongly that Roman primacy was already asserted. However, it should be noted that, because of the controversy of this claim, the Pope did not personally attend this ecumencial council that was held in the capital of the eastern empire, rather than at Rome. It was not until 440 that Leo the Great more clearly articulated the extension of papal authority as doctrine, promulgating in edicts and in councils his right to exert "the full range of apostolic powers that Jesus had first bestowed on the apostle Peter". It was at the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 that Leo I (through his emissaries) stated that he was "speaking with the voice of Peter". At this same Council, an attempt at compromise was made when the bishop of Constantinople was given a primacy of honour only second to that of the Bishop of Rome, because "Constantinople is the New Rome." Ironically, Roman papal authorities rejected this language since it did not clearly recognize Rome's claim to juridical authority over the other churches.[42]

Church Fathers

Virgin and Child. Wall painting from the early catacombs, Rome, 4th century.

Virgin and Child. Wall painting from the early catacombs, Rome, 4th century.

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, or Fathers of the Church are the early and influential theologians and writers in the Christian Church, particularly those of the first five centuries of Christian history. The term is used of writers and teachers of the Church, not necessarily saints. Teachers particularly are also known as doctors of the Church, although Athanasius called them men of little intellect.[43]

Influential texts and writers between c.200 and 325 (the First Council of Nicaea) include: Arius (256–336)

Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

Main article: Nicene and Post-Nicene FathersLate Antique Christianity produced a great many renowned Church Fathers who wrote volumes of theological texts, including SS. Augustine, Gregory Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and others. What resulted was a golden age of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Some of these fathers, such as John Chrysostom and Athanasius, suffered exile, persecution, or martyrdom from heretical Byzantine Emperors. Many of their writings are translated into English in the compilations of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.

Influential texts and writers between 325 AD and c.500 AD include:

- Athanasius (298–373)

- The Cappadocian Fathers (late 4th century)

- Ambrose (c. 340–397)

- Chrysostom (347 407)

Greek Fathers

Those who wrote in Greek are called the Greek (Church) Fathers. Famous Greek Fathers include: Irenaeus of Lyons, Clement of Alexandria, the heterodox Origen, Athanasius of Alexandria, John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria and the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil of Caesarea, Gregory Nazianzus, Peter of Sebaste & Gregory of Nyssa).

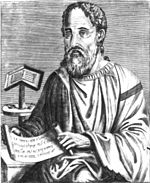

Athanasius of Alexandria

Main article: Athanasius of AlexandriaAthanasius of Alexandria (c 293–2 May 373) was a theologian, Pope of Alexandria, and a noted Egyptian leader of the 4th century. He is best remembered for his role in the conflict with Arianism. At the First Council of Nicaea (325), Athanasius argued against the Arian doctrine that Christ is of a distinct substance from the Father.[23]

John Chrysostom

Main article: John ChrysostomJohn Chrysostom (c 347– c 407), archbishop of Constantinople, is known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, and his ascetic sensibilities. After his death (or, according to some sources, during his life) he was given the Greek surname chrysostomos, meaning "golden mouthed", rendered in English as Chrysostom.[44][45]

Chrysostom is known within Christianity chiefly as a preacher, theologian, and liturgist, particularly in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Outside the Christian tradition Chrysostom is noted for eight of his sermons which played a considerable part in the history of Christian antisemitism, and were extensively misused by the Nazis in their ideological campaign against the Jews.[46][47]

Latin Fathers

Those fathers who wrote in Latin are called the Latin (Church) Fathers. Famous Latin Fathers include Tertullian (who later in life converted to Montanism), Cyprian of Carthage, Gregory the Great (5th century), Augustine of Hippo, Ambrose of Milan, and Jerome.

Ambrose of Milan

Main article: Ambrose of MilanSaint Ambrose[48] (c. 338 – 4 April 397), was a bishop of Milan who became one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century. He is counted as one of the four original doctors of the Church.

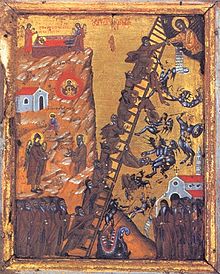

Monasticism

Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early monastics living in the Egyptian desert; although they did not write as much, their influence was also great. Among them are St. Anthony the Great and St. Pachomius. A great number of their usually short sayings is collected in the Apophthegmata Patrum ("Sayings of the Desert Fathers").

Early Christian monasticism

The first efforts to create a proto-monastery were by Saint Macarius, who established individual groups of cells such as those at Kellia (founded in 328.) The intention was to bring together individual ascetics who, although pious, did not, like Saint Anthony, have the physical ability or skills to live a solitary existence in the desert . At Tabenna. in upper Egypt, sometime around 323 AD, Saint Pachomius, chose to mould his disciples into a more organized community in which the monks lived in individual huts or rooms (cellula in Latin,) but worked, ate, and worshipped in shared space. Guidelines for daily life were created, and separate monasteries were created for men and women. This method of monastic organization is called cenobitic or "community-based." All the principal monastic orders are cenobitic in nature. In Catholic theology, this community-based living is considered superior because of the obedience practiced and the accountability offered. The head of a monastery came to be known by the word for "Father;" – in Syriac, Abba; in English, "Abbot."

This one community was so successful he was called in to help organize others, and by one count by the time he died in 346 there were thought to be 3,000 such communities dotting Egypt, especially the Thebaid. Within the span of the next generation this number increased to 7,000. From there monasticism quickly spread out first to Palestine and the Judean Desert, Syria, North Africa and eventually the rest of the Roman Empire.

Eastern monasticism

See also: Monk#Monasticism_in_Eastern_Christianity and Eastern Orthodox monksOrthodox monasticism does not have religious orders as in the West,[49] so there are no formal Monastic Rules (Regulae); rather, each monk and nun is encouraged to read all of the Holy Fathers and emulate their virtues. There is also no division between the "active" and "contemplative" life. Orthodox monastic life embraces both active and contemplative aspects.

Historical development

Among the first to set forth precepts for the monastic life was Saint Basil the Great, a man from a professional family who was educated in Caesarea, Constantinople, and Athens. Saint Basil visited colonies of hermits in Palestine and Egypt but was most strongly impressed by the organized communities developed under the guidance of Saint Pachomius. Saint Basil's ascetical writings set forth standards for well-disciplined community life and offered lessons in what became the ideal monastic virtue: humility.

Saint Basil wrote a series of guides for monastic life (the Lesser Asketikon the Greater Asketikon the Morals, etc.) which, while not "Rules" in the legalistic sense of later Western rules, provided firm indications of the importance of a single community of monks, living under the same roof, and under the guidance—and even discipline—of a strong abbot. His teachings set the model for Greek and Russian monasticism but had less influence in the Latin West.

The Eastern Monastic or Ascetic tradition

With the elevation of Christianity to the status of a legal religion within the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great, with the edict of Milan (313), many Orthodox felt a new decline in the ethical life of Christians. In reaction to this decline, many refused to accept any compromises and fled the world or societies of mankind, to become monastics. Monasticism thrived, especially in Egypt, with two important monastic centers, one in the desert of Wadi Natroun, by the Western Bank of the Nile, with Abba Ammoun (d. 356) as its founder, and one in the desert of Skete, south of Nitria, with Saint Makarios of Egypt (d. ca. Egypt 330) as its founder. These monks were anchorites, following the monastic ideal of St. Anthony the Great, Paul of Thebes and Saint Pachomius. They lived by themselves, gathering together for common worship on Saturdays and Sundays only. This is not to say that Monasticism or Orthodox Asceticism was created whole cloth at the time of legalization but rather at the time it blossomed into a mass movement. Charismatics as the ascetic movement was considered had no clerical status as such. Later history developed around the Greek (Mount Athos) and Syrian (Cappadocia) forms of monastic life, along with the formation of Monastic Orders or monastic organization. The three main forms of Ascetics' traditions being Skete, Cenobite and Hermit respectively.

Western monasticism

Gaul

The earliest phases of monasticism in Western Europe involved figures like Martin of Tours, who after serving in the Roman legions converted to Christianity and established a hermitage near Milan, then moved on to Poitiers where he gathered a community around his hermitage. He was called to become Bishop of Tours in 372, where he established a monastery at Marmoutiers on the opposite bank of the Loire River, a few miles upstream from the city. His monastery was laid out as a colony of hermits rather than as a single integrated community.

John Cassian began his monastic career at a monastery in Palestine and Egypt around 385 to study monastic practice there. In Egypt he had been attracted to the isolated life of hermits, which he considered the highest form of monasticism, yet the monasteries he founded were all organized monastic communities. About 410 he established two monasteries near Marseilles, one for men, one for women. In time these attracted a total of 5,000 monks and nuns. Most significant for the future development of monasticism were Cassian's Institutes, which provided a guide for monastic life and his Conferences, a collection of spiritual reflections.

Honoratus of Marseilles was a wealthy Gallo-Roman aristocrat, who after a pilgrimage to Egypt, founded the Monastery of Lérins, on an island lying off the modern city of Cannes. The monastery combined a community with isolated hermitages where older, spiritually-proven monks could live in isolation.

One Roman reaction to monasticism was expressed in the description of Lérins by Rutilius Namatianus, who served as prefect of Rome in 414:

-

-

- A filthy island filled by men who flee the light.

- Monks they call themselves, using a Greek name.

- Because they will to live alone, unseen by man.

- Fortune's gifts they fear, dreading their harm:

- Mad folly of a demented brain,

- That cannot suffer good, for fear of ill.

-

Lérins became, in time, a center of monastic culture and learning, and many later monks and bishops would pass through Lérins in the early stages of their career. Honoratus was called to be Bishop of Arles and was succeeded in that post by another monk from Lérins. Lérins was aristocratic in character, as was its founder, and was closely tied to urban bishoprics.

Defining scripture

Main article: Development of the Christian biblical canon A page from Codex Sinaiticus, א, showing text from Esther. Written c. 330-360, it is one of the earliest and most important Biblical manuscript. Now at the British Library and other locations, the manuscript was discovered at Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, in 1844.

A page from Codex Sinaiticus, א, showing text from Esther. Written c. 330-360, it is one of the earliest and most important Biblical manuscript. Now at the British Library and other locations, the manuscript was discovered at Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, in 1844.

In 331, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Christian Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius (Apol. Const. 4) recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists, and that Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta and Codex Alexandrinus, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[50]

In order to form a New Testament canon of uniquely Christian works, proto-orthodox Christians went through a process that was complete in the West by the beginning of the fifth century.[51] Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, in his Easter letter of 367[52], which was approved at the Quinisext Council, listed the same twenty-seven New Testament books as found in the Canon of Trent. The first council that accepted the present canon of the New Testament may have been the Synod of Hippo Regius in North Africa (AD 393); the acts of this council, however, are lost. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Councils of Carthage in 397 and 419.[53]

Bishops and Structure

After legalisation in 313, the Church inside the Empire adopted the same organisational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called dioceses, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division. The bishops, who were located in major urban centres as per pre-legalisation tradition, thus oversaw each diocese as Metropolitan bishops. The bishop's location was his "seat", or "see"; among the sees. The prestige of important Christian centers depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors according to the doctrine of Apostolic succession, e.g., Mark as founder of the See of Alexandria, Peter of the See of Rome, etc. There were other significant elements: Jerusalem was the location of Christ's death and resurrection, the site of a first century council, location of the first church, etc. Antioch was where Jesus' followers were first labelled as Christians, it was used in a derogatory way to berate the followers of Jesus the Christ. Rome was where Peter and Paul had been martyred, Constantinople was the "New Rome" where Constantine had moved his capital c. 330, and, lastly, all these cities had important relics.

Soon, Constantine erected a new capital at Byzantium, a strategically placed city on the Bosporus. He renamed his new capital Nova Roma ("New Rome"), but the city would become known as Constantinople. The Second Ecumenical Council, held at the new capital in 381, now elevated the see of Constantinople itself, to a position ahead of the other chief metropolitan sees, except that of Rome.[54] Mentioning in particular the provinces of Asia, Pontus and Thrace, it decreed that the synod of each province should manage the ecclesiastical affairs of that province alone, except for the privileges already recognized for Alexandria and Antioch.[55]

Tensions between the East and the West

The cracks and fissures in Christian unity which led to the East-West Schism started to become evident as early as the 4th century. Although 1054 is the date usually given for the beginning of the Great Schism, there is, in fact, no specific date on which the schism occurred. What really happened was a complex chain of events whose climax culminated with the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204 .

The events leading to schism were not exclusively theological in nature. Cultural, political, and linguistic differences were often mixed with the theological. Any narrative of the schism which emphasizes one at the expense of the other will be fragmentary. Unlike the Coptics or Armenians who broke from the Church in the 5th century and established ethnic churches at the cost of their universality and catholicity, the eastern and western parts of the Church remained loyal to the faith and authority of the seven ecumenical councils. They were united, by virtue of their common faith and tradition, in one Church.

The Stone of the Anointing, believed to be the place where Jesus' body was prepared for burial. It is the 13th Station of the Cross.

The Stone of the Anointing, believed to be the place where Jesus' body was prepared for burial. It is the 13th Station of the Cross.

The Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the ecclesiastics of the Orthodox church are based in the ancient Church of the Holy Sepulchre constructed in 335 AD.

New Rome

When the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great embraced Christianity, he summoned the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 325 to resolve a number of issues which troubled the Church. The bishops at the council confirmed the position of the metropolitan sees of Rome and Alexandria as having authority outside their own province, and also the existing privileges of the churches in Antioch and the other provinces.[56] These sees were later called Patriarchates and were given an order of precedence: Rome, as capital of the empire was naturally given first place, then came Alexandria and Antioch. In a separate canon the Council also approved the special honor given to Jerusalem over other sees subject to the same metropolitan.[57]

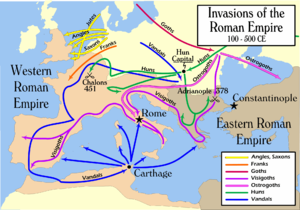

Empires East and West

Disunion in the Roman Empire further contributed to disunion in the Church. The Emperor Diocletian famously divided the administration of the eastern and western portions of the Empire in the early 4th century, though subsequent leaders (including Constantine) aspired to and sometimes gained control of both regions. Theodosius the Great, who established Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, died in 395 and was the last Emperor to rule over a united Roman Empire; following his death, the division into western and eastern halves, each under its own Emperor, became permanent. By the end of the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire had been overrun by the Germanic tribes, while the Eastern Roman Empire (known also as the Byzantine Empire) continued to thrive. Thus, the political unity of the Roman Empire was the first to fall.

In the West, the collapse of civil government left the Church practically in charge in many areas, and bishops took to administering secular cities and domains.[23] When royal and imperial rule reestablished itself, it had to contend with power wielded independently by the Church. In the East, however, imperial and, later, Islamic rule dominated the Eastern bishops of Byzantium.[23] Where as the Orthodox regions that were predominately Slavic experienced period foreign dominance as well as period without infrastructure (see the Tatars and Russia).

Rise of Rome

Father Thomas Hopko, a leading Orthodox theologian, has written: "The church of Rome held a special place of honor among the earliest Christian churches. It was first among the communities that recognized each other as catholic churches holding the orthodox faith concerning God's Gospel in Jesus. According to St Ignatius, the bishop of Antioch who died a martyr's death in Rome around the year 110, 'the church which presides in the territories of the Romans' was 'a church worthy of God, worthy of honor, worthy of felicitation, worthy of praise, worthy of success, worthy of sanctification, and presiding in love, maintaining the law of Christ, bearer of the Father's name.' The Roman church held this place of honor and exercised a 'presidency in love' among the first Christian churches for two reasons. It was founded on the teaching and blood of the foremost Christian apostles Peter and Paul. And it was the church of the capital city of the Roman empire that then constituted the 'civilized world (oikoumene)'."[58]

In the 4th century when the Roman emperors were trying to control the Church, theological questions were running rampant throughout the Roman Empire.[59] The influence of Greek speculative thought on Christian thinking led to all sorts of divergent and conflicting opinions.[60] Christ's commandment to love others as He loved, seemed to have been lost in the intellectual abstractions of the time. Theology was also used as a weapon against opponent bishops, since being branded a heretic was the only sure way for a bishop to be removed by other bishops. Incompetence was not sufficient grounds for removal.[citation needed]

In the early church up until the ecumenical councils, Rome was regarded as an important centre of Christianity, especially since it was the capital of the Roman Empire. The eastern and southern Mediterranean bishops generally recognized a persuasive leadership and authority of the Bishop of Rome, because the teaching of the bishop of Rome was almost invariably correct.[citation needed] But the Mediterranean Church did not regard the Bishop of Rome as any sort of infallible source, nor did they acknowledge any juridical authority of Rome.

After the sole emperor of all the Roman Empire Constantine built the new imperial capital on the Bosphorous, i.e. Constantinople, the centre of gravity in the empire was fully recognised to have completely shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Rome lost the Senate to Constantinople and lost its status and gravitas as imperial capital.

The patriarchs of Constantinople often tried to adopt an imperious position over the other patriarchs. In the case of Nestorius, whose actual teaching is now recognised to be not overtly heretical, although it is clearly deficient, (Saint Cyril called it 'slippery'),[61] other patriarchs were able to make the charge of heresy stick and successfully had him deposed. This was probably more because his Christology was delivered with a heavy sarcastic arrogance which matched his high-handed personality.[61]

The opinion of the Bishop of Rome was often sought, especially when the patriarchs of the Eastern Mediterranean were locked in fractious dispute. The bishops of Rome never obviously belonged to either the Antiochian or the Alexandrian schools of theology, and usually managed to steer a middle course between whatever extremes were being propounded by theologians of either school. Because Rome was remote from the centres of Christianity in the eastern Mediterranean, it was frequently hoped its bishop would be more impartial. For instance, in 431, Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria, appealed to Pope Celestine I, as well as the other patriarchs, charging Nestorius with heresy, which was dealt with at the Council of Ephesus.

The opinion of the bishop of Rome was always canvassed, and was often longed for. However the Bishop of Rome's opinion was by no means automatically right. For instance, the Tome of Leo of Rome was highly regarded, and formed the basis for the ecumenical council's formulation. But it was not universally accepted and was even called "impious" and "blasphemous" by some.[62] The next ecumenical council corrected a possible imbalance in Pope Leo's presentation. Although the Bishop of Rome was well respected even at this early date, the concept of the primacy of the Roman See and Papal Infallibility were only developed much later.

Following the Sack of Rome by invading European Goths, Rome slid into the Dark Ages which afflicted most parts of Western Europe, and became increasingly isolated and irrelevant to the wider Mediterranean Church. This was a situation which suited and pleased a lot of the Eastern Mediterranean patriarchs and bishops.[63]

It was not until the rise of Charlemagne and his successors that the Church of Rome arose out of obscurity on the back of the military successes of the western Mediterranean adventurers.

Damasus I

Pope Damasus I (366–384) was first to claim that Rome's primacy rested solely on Peter, and was the first pope to refer to the Roman church as "the Apostolic See". The prestige of the city itself was no longer sufficient; but in the doctrine of apostolic succession the popes had an unassailable position.

Primacy of Peter the apostle

Pope Damasus I (366–384) was first to claim that Rome's primacy rested solely on Peter, and was the first pope to refer to the Roman church as "the Apostolic See".

Decretals

The bishops of Rome sent letters which, though largely ineffectual, provided historical precedents which were used by later supporters of papal primacy. These letters were known as ‘decretals’ from at least the time of Siricius (384–399) to Leo I provided general guidelines to follow which later would become incorporated into canon law).[64] Thus it was “this attempt to implement the authority of the bishop of Rome, or at least the claim of authority, to lands outside Italy, which allows us to use the word ‘pope’ for bishops starting with Damasus (366–384) or Siricius.” Pope Siricisus declared that no bishop could take office without his knowledge. Not until Pope Symmachus would a bishop of Rome presume to bestow a pallium (woolen garment worn by a bishop) on someone outside Italy.

St. Optatus

Saint Optatus clearly believed in a "Chair of Peter", calling it a gift of the Church and saying, as summarized by Henry Wace, that "Parmenian must be aware that the episcopal chair was conferred from the beginning on Peter, the chief of the apostles, that unity might be preserved among the rest and no one apostle set up a rival."[65] "You cannot deny that you are aware that in the city of Rome the episcopal chair was given first to Peter; the chair in which Peter sat, the same who was head – that is why he is also called Cephas – of all the Apostles; the one chair in which unity is maintained by all. Neither do other Apostles proceed individually on their own; and anyone who would set up another chair in opposition to that single chair would, by that very fact, be a schismatic and a sinner".[66]

Spread of Christianity

In the 4th century, the early process of Christianization of the various Germanic people was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian Roman Empire amongst European pagans. Until the decline of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes who had migrated there (with the exceptions of the Saxons, Franks, and Lombards, see below) had converted to Christianity.[67] Many of them, notably the Goths and Vandals, adopted Arianism instead of the Trinitarian (a.k.a. Nicene or orthodox) beliefs that came to dominate the Roman Imperial Church.[67] The gradual rise of Germanic Christianity was, at times, voluntary, particularly amongst groups associated with the Roman Empire.

Wulfila or Ulfilas was the son or grandson of Christian captives from Sadagolthina in Cappadocia. In 337 or 341, Wulfila became the first bishop of the (Christian) Goths. By 348, one of the (Pagan) Gothic kings (reikos) began persecuting the Christian Goths, and Wulfila and many other Christian Goths fled to Moesia Secunda (in modern Bulgaria) in the Roman Empire.[68][69] Other Christians, including Wereka, Batwin, and Saba, died in later persecutions.

Between 348 and 383, Wulfila translated the Bible into the Gothic language.[69][70] Thus some Arian Christians in the west used the vernacular languages, in this case including Gothic and Latin, for services, as did Christians in the eastern Roman provinces, while most Christians in the western provinces used Latin.

Christian missionaries to the Goths

- Ulfilas (Gothic, 341–383)

Christianity outside the Roman Empire

The Armenian and Ethiopian churches are the only instances of imposition of Christianity by sovereign rulers predating the council of Nicaea. The initial conversion of the Roman Empire occurred mostly in urban areas of Europe, where the first converts occurred through the conversion of most of the Jewish population. Later conversions happened among the Grecian-Roman-Celtic populations over centuries, again mostly among its urban population and only spread to rural populations in much later centuries. The term "pagan" is from Latin, it means "villager, rustic, civilian" and is derived from this historical transition. The root of that word is present in today's word "paisan" or "paisano". Consequently, while the initial converts were found among the Jewish populations, the development of the Orthodox Church as an aspect of State society occurred through the co-option of State Religion into the ethos of Christianity and only then was conversion of the large rural population accomplished.

The early Christianization of the various Germanic peoples was achieved by various means, and was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian Roman Empire amongst European pagans. The early rise of Germanic Christianity was, thus, mainly due to voluntary conversion on a small scale.

In the 4th century some Eastern Germanic tribes, notably the Goths, an East Germanic tribe, adopted Arianism.

The Germanic migrations of the 5th century were triggered by the destruction of the Gothic kingdoms by the Huns in 372–375. The city of Rome was captured and looted by the Visigoths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455.

9th century depiction of Christ as a heroic warrior (Stuttgart Psalter, fol. 23, illustration of Psalm 91:13)

9th century depiction of Christ as a heroic warrior (Stuttgart Psalter, fol. 23, illustration of Psalm 91:13)

Georgian Orthodox Church

St Nino of Cappadocia

St Nino of Cappadocia

The first Eparchy was founded in Georgia, traditionally by the Apostle Andrew. In 327, Christianity was adopted as the state religion by the rulers of Iberia (Eastern Georgia). From the 320s, the Georgian Orthodox Church was under the jurisdiction of the Apostolic See of Antioch.

The Great Persecution

The great persecution fell upon the Christians in Persia about the year 340. Though the religious motives were never unrelated, the primary cause of the persecution was political. When Rome became Christian, its old enemy turned anti-Christian.

Up to then the situation had been reversed. For the first 300 hundreds after Christ it was in the West that Christians were persecuted. For two hundred and fifty years Persia had been a refuge from Roman persecution. The Parthians were too religiously tolerant to persecute, and their less tolerant Sassanian successors on the throne were too busy fighting Rome, Persian emperors were inclined to regard them as friends of Persia.

It was about 315 that an ill-advised letter from the Christian emperor Constantine to his Persian counterpart Shapur II probably triggered the beginnings of an ominous change in the Persian attitude toward Christians. Constantine believed he was writing to help his fellow believers in Persia but succeeded only in exposing them. He wrote to the young shah:

-

- "I rejoice to hear that the fairest provinces of Persia are adorned with...Christians...Since you are so powerful and pious, I commend them to your care, and leave them in your protection[9]".

It was enough to make any Persian ruler conditioned by 300 years of war with Rome suspicious of the emergence of a fifth column. Any lingering doubts must have been dispelled when about twenty years later when Constantine began to gather his forces for war in the East. Eusebius records that Roman bishops were prepared to accompany their emperor to "battle with him and for him by prayers to God whom all victory proceeds".[10] And across the border in Persian territory the forthright Persian preacher Aphrahat recklessly predicted on the basis of his reading of Old testament prophecy that Rome would defeat Persia.[11]

It is little wonder then, that when the persecutions began shortly thereafter, the first accusation brought against the Christians was that they were aiding the Roman enemy. The shah Shapur II's response was to order a double taxation on Christians and to hold the bishop responsible for collecting it. He knew they were poor and that the bishop would be hard-pressed to find the money. Bishop Simon refused to be intimidated. He branded the tax as unjust and declared, "I am no tax collector but a shepherd of the Lord's flock." Then the killings began.

A second decree ordered the destruction of churches and the execution of clergy who refused to participate in the national worship of the sun. Bishop simon was seized and brought before the shah and was offered gifts to make a token obeisance to the sun, and when he refused, they cunningly tempted him with the promise that if he alone would apostatize his people would not be harmed, but that if he refused he would be condemning not just the church leaders but all Christians to destruction. At that, the Christians themselves rose up and refused to accept such a deliverance as shameful. So according to the tradition in the year 344, he was led outside the city of Susa along with a large number of Christian clergy. Five bishops and one hundred priests were beheaded before his eyes, and last of all he himself was put to death.[12]

For the next two decades and more, Christians were tracked down and hunted from one end of the empire to the other. At times the pattern was general massacre. More often, as Shapur decreed, it was intensive organized elimination of the leadership of the church, the clergy. A third category of suppression was the search for that part of the Christian community that was most vulnerable to persecution, Persians who had been converted from the national religion, Zoroastrianism. As we have already seen, the faith had spread first among non-Persian elements in the population, Jews and Syrians. But by the beginning of the 4th century, Iranians in increasing numbers were attracted to the Christian faith. For such converts, church membership could mean the loss of everything – family, property rights, and life itself. Converts from the "national faith" had no rights and, in the darker years of the persecution, were often put to death. The major agents in the slaughter were Zoroastrian clergy, but sometimes Christians suspected the Jews and accused them of acting as informers.[citation needed]

The martyrdom of Simon and the years of persecution that followed wiped out the beginnings of the central national organization the Persian church had only so recently achieved. As fast as the Christians of the capital elected a new bishop after Simon, the man was seized and killed. Inflaming the anti-Roman political motivation of the government's role in the persecutions was a deep undercurrent of Zoroastrian fanaticism and hatred of other religions.[citation needed]

Sometime before the death of Shapur II in 379, the intensity of the persecution slackened. Tradition calls it a forty-year persecution, lasting from 339–379 and ending only with Shapur's death.

When at last the years of suffering ended around the year 401, the historian Sozomen, who lived near enough to that time of tribulation to remember the tales of those who experienced it, wrote that the multitude of martyrs had been "beyond enumeration".[13] One estimate is that as many as 190,000 Persian Christians died in the terror. It was worse than any suffering in the West under Rome.[citation needed]

Conditioning factors of missionary expansion

Several important factors help to explain the extensive growth in the Church of the East during the first twelve hundred years of the Christian era. Geographically, and possibly even numerically, the expansion of this church outstripped that of the church in the West in the early centuries. The outstanding key to understanding this expansion is the active participation of the laymen – the involvement of a large percentage of the church's believers in missionary evangelism.[14] The following significant factors inducing that church growth are all based largely on the fact that it was a lay as well as a clerical movement.

3) Persecution strengthened and spread the Christian movement in the East. A great influx of Christian refugees from the Roman persecutions of the first two centuries gave vigour to the Mesopotamian church And persecution within the Persian empire saw thousands slain for the faith (at least 16,000 under the reign of Sapor II, AD 307–379) and numberless thousands more reported or fleeing as refugees to witness as far as Arabia, India, and other Central Asian countries. Following a period of relative quiet in the empire under Bahram V (420–38), more terrible persecution broke out, culminating in the massacre of ten bishops and 153,000 Christians within a few days.

During the early centuries Christianity also penetrated Arabia from numerous points on its periphery. The kingdom of Hira in northeastern Arabia and near the border of Mesopotamia flourished from the end of the 3rd to the end of the 6th and was apparently evangelized by Christians from the Tigris-Euphrates Valley in the 4th century. The kingdom of Ghassan on the northwest frontier was also a sphere of missionary activity. In fact, by AD 500 many churches were also in existence along the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf and in Oman, with all connected with the Church of the East in the Persian Empire. Arabian bishops were found among those in attendance at important church councils in Mesopotamia. in the 7th century, however, with the rise of Islam seriously inhibited the growth of the church in Arabia. The regulations imposed throughout Persian and Arab territories upon non-Muslims however, progressively reduced both the numbers and public roles of Christians. Yet it was only in the wake of the Crusades that the antagonism between Christian and Muslim become sharp enough to bring comprehensive discrimination and the consequent dismantling of Christian influence. Existing churches were gradually eliminated by Muslim oppression. Many of the remaining Christians fled the country and found refuge in Mesopotamia.

The expansion of Christianity in Central Asia

The agents of missionary expansion in central Asia and the far east were not only monks and clergy trained in the mesopotamian monastic schools, but also in many cases Christian merchants and artisans, often with considerable biblical training. They frequently found employment among people less advanced in education, serving in government offices and as teachers and secretaries and more advanced medical care. they also helped to solve the problem of illiteracy in backward lands by inventing simplified alphabets based on the Syriac language.[71]

Persecution often thrust them forth into new and unevangelized lands to find refuge. The dissemination of the gospel by largely Syriac-using people had its advantages, but it was also a hindrance to indigenizing the church in the new areas. Because Syriac never became dominant, competition from ethnic religions was always a serious problem. For these reasons of political vicissitude, in later centuries Christianity suffered an almost total eclipse in Asia until the modern period. The golden age of early missions in central Asia extended from the end of the fourth to the latter part of the 9th century, although in the Far East Christianity again became resurgent in the latter half of the 13th century. An important factor which finally inhibited the permanent establishment of the Church of the East in central Asia and the far East was the expansion of Islam and Mahayana Buddhism.

Christianity had an early and extensive dissemination throughout the vast territory north of Persia and west and East of the Oxus River. As early as the 4th century cities like Merv, Herat and Samarkand had bishops and later became metropolitanates. Christians were found among the Hephthalite Huns from the 5th century, and the Mesopotamian patriarch assigned two bishops (John of Resh-aina and Thomas the Tanner) to both peoples, with the result that many were baptized. They also devised and taught a written language for the Huns and with the help of an Armenian bishop, taught also agricultural methods and skills.

4th century Timeline- 296–304 Pope Marcellinus, offered pagan sacrifices for Diocletian

- 303 Saint George, patron saint of England, and other states

- 303–312 Diocletian's Massacre of Christians, included burning of scriptures (EH 8.2)

- 304 – Armenia accepts Christianity as state religion [15]

- 304? Victorinus, bishop of Pettau

- 304? Pope Marcellinus, having repented from his previous defection, suffered martyrdom with several companions.

- 306 – The first bishop of Nisibis is ordained[72]

- 306 Synod of Elvira, prohibited relations between Christians and Jews

- 290–345? St Pachomius, founder of Christian monasticism

- 310 Maxentius deports Pope Eusebius and Heraclius [16] [17] to Sicily (relapse controversy)

- 312 Lucian of Antioch, founded School of Antioch, martyred

- 312 Vision of Constantine: while gazing into the sun he saw a cross with the words by this sign conquer, see also Labarum, he was later called the 13th Apostle and Equal-to-apostles

- 313 Edict of Milan, Constantine and Licinius end persecution, establish toleration of Christianity

- 313? Lateran Palace given to Pope Miltiades for residence by Constantine

- 314 Council of Arles [18], called by Constantine against Donatist schism

- 314 Arsacid Armenia first to adopt Christianity as state religion (mainstream date; traditionally 301)

- 313 – Emperor Constantine issues Edict of Milan, legalizing Christianity in the Roman Empire[73]

- 317? Lactantius

- 314 – Tiridates III of Armenia and King Urnayr of Caucasian Albania converted by Gregory the Illuminator [19]

- 321 Constantine decreed Sunday as state "day of rest" (CJ3.12.2), see also Sol Invictus

- 251–424? Synods of Carthage

- 314–340? Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, church historian, cited Caesarean text-type, wrote Ecclesiastical History in 325[74]

- 325 The First Council of Nicaea

- 325 The Kingdom of Aksum (Modern Ethiopia) declares Christianity as the official state Religion becoming the second country to do so

- 325 Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, ordered by Constantine

- 326, November 18 Pope Sylvester I consecrates the Basilica of St. Peter built by Constantine the Great over the tomb of the Apostle.

- 327 – Georgian King Mirian III of Iberia converted by Nino[75]

- 330 – Ethiopian King Ezana of Axum makes Christianity an official religion

- 330 Old Church of the Holy Apostles, dedicated by Constantine

- 330, May 11: Constantinople solemly inaugurated. Constantine moves the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, renaming it New Rome

- 331 Constantine commissioned Eusebius to deliver 50 Bibles for the Church of Constantinople[76]

- 332 – Two young Roman Christians, Frumentius and Aedesius, are the sole survivors of a ship destroyed in the Red Sea due to tensions between Rome and Aksum. They are taken as slaves to the Ethiopian capital of Axum to serve in the royal court.[77]

- 334 – The first bishop is ordained for Merv / Transoxiana (area of modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and southwest Kazakhstan)[78]

- 335 Council in Jerusalem, reversed Nicaea's condemnation of Arius, consecrated Jerusalem Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- 337 Mirian III of Georgia, third to adopt Christianity as state religion

- 337, May 22: Constantine the Great dies. Baptized shortly prior to his death

- 341–379 Shapur II's persecution of Persian Christians

- 343? Council of Sardica

- 337 – Emperor Constantine baptized shortly before his death[79]

- 341 – Ulfilas begins work with the Goths in present-day Romania[80]

- 328–373 Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, first cite of modern 27 book New Testament canon

- 350? Julius Firmicus Maternus

- 350? Codex Sinaiticus(א), Codex Vaticanus(B): earliest Christian Bibles, Alexandrian text-type

- 350? Ulfilas, Arian, apostle to the Goths, translated Greek NT to Gothic

- 350? Comma Johanneum 1Jn5:7b-8a(KJV)

- 350? Aëtius, Arian, "Syntagmation": "God is agennetos (unbegotten)", founder of Anomoeanism

- 350? School of Nisibis founded

- 350 – Bible is translated into Saidic, an Egyptian language[81]

- 354 – Theophilus "the Indian" reports visiting Christians in India [20]; Philostorgius mentions a community of Christians on the Socotra islands, south of Yemen in the Arabian Sea [21]

- 357 Council of Sirmium, issued so-called Blasphemy of Sirmium or Seventh Arian Confession,[82] called high point of Arianism

- 359 Council of Rimini, Dated Creed (Acacians)

- 360 Julian the Apostate becomes the last non-Christian Roman Emperor.

- 364 – Conversion of Vandals to Christianity begins during reign of Emperor Valens[83]

- 353–367 Hilary, bishop of Poitiers

- 355–365 Antipope Felix II, Arian, supported by Constantius II, consecrated by Acacius of Caesarea

- 363–364 Council of Laodicea, canon 29 decreed anathema for Christians who rest on the Sabbath, disputed canon 60 named 26 NT books (excluded Revelation)

- 366–367 Antipope Ursicinus, rival to Pope Damasus I

- 370? Doctrine of Addai at Edessa proclaims 17 book NT canon using Diatessaron (instead of the 4 Gospels) + Acts + 15 Pauline Epistles (inc. 3 Corinthians) Syriac Orthodox Church

- 370 – Wulfila translates the Bible into Gothic, the first Bible translation done specifically for missionary purposes

- 378 - Jerome writes, "From India to Britain, all nations resound with the death and resurrection of Christ"[77]

- 367–403 Epiphanius, bishop of Salamis, wrote Panarion against heresies

- 370–379 Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea

- 372–394 Gregory, Bishop Of Nyssa

- 373 Ephrem the Syrian, cited Western Acts

- 374–397 Ambrose, bishop & governor of Milan

- 375–395 Ausonius, Christian governor of Gaul

- 379–381 Gregory Nazianzus, Bishop of Constantinople

- 380, February 27: Emperor Theodosius I issues the edict De Fide Catolica declaring Christianity as the official state religion of the Roman Empire[84]

- 380, November 24: Emperor Theodosius I is baptised.

- 380 – Roman Emperor Theodosius I makes Christianity the official state religion[85]

- 381 First Council of Constantinople, 2nd ecumenical, Jesus had true human soul, Nicene Creed of 381

- 382 Council of Rome under Pope Damasus I sets the Biblical Canon, listing the inspired books of the Old Testament and the New Testament (disputed)

- 382 – Jerome is commissioned to translate the Gospels (and subsequently the whole Bible) into Latin (Price, p. 78</ref>

- 383? Frumentius, Apostle of Ethiopia

- 385 Priscillian, first heretic to be executed?

- 386 – Augustine of Hippo converted[86]

- 390? Apollinaris, bishop of Laodicea, believed Jesus had human body but divine spirit

- 391: The Theodosian decrees outlaw most pagan rituals still practiced in Rome.

- 390 – Nestorian missionary Abdyeshu (or Abdisho) builds a monastery on the island of Bahrain

- 397 – Ninian evangelizes the Southern Picts of Scotland; three missionaries sent to the mountaineers in the Trento region of northern Italy are martyred[87]

- 397? Saint Ninian evangelizes Picts in Scotland

- 400 – Hayyan begins proclaiming gospel in Yemen after having been converted in Hirta on the Persian border; in starting a school for native Gothic evangelists, John Chrysostom writes, "'Go and make disciples of all nations' was not said for the Apostles onlyu, but for us also"[77]

- 400: Jerome's Vulgate Latin edition and translation of the Bible is published.

- 400? Ethiopic Bible: in Ge'ez, 81 books, standard Ethiopian Orthodox Bible

- 400? Peshitta Bible in Syriac (Aramaic), Syr(p), OT + 22 NT, excludes: 2Pt, 2–3Jn, Jude, Rev; standard Syriac Orthodox Church Bible

References

- ^ O'Leary (2000), pp. 131–137.

- ^ Price (2005), pp. 52–55.

- ^ Dwyer (1998), pp. 109–111.

- ^ Anderson (2010), p. 604.

Amory (), pp. 259–262. - ^ Hopkins(1998), p. 191

- ^ Irvin (2002), p. 161.

- ^ Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") ch. 35–34

- ^ a b R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 55

- ^ cf. Eusebius, Life of Constantine

- ^ R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) pp. 55–56

- ^ R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 56

- ^ Payton (2007), p. 29.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) pp. 14–15

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) p. 15

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) p. 16

- ^ Irvin (2002), p. 164, ch. 15.

- ^ Carroll (1987), p. 11.

- ^ Irvin (2002), p. 164, ch. 16.

- ^ Bettenson (1967), p. 22.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/theodcodeXVI.html. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ "Lecture 27: Heretics, Heresies and the Church". 2009. http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture27b.html. Retrieved 2010-04-24. Review of Church policies towards heresy, including capital punishment.

- ^ Wordsworth (1887), p. 392.

- ^ a b c d Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ^ "The oneness of Essence, the Equality of Divinity, and the Equality of Honor of God the Son with the God the Father." Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky pages 92–95

- ^ Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky pages 92–95: "This heretical teaching of Arius disrupted the whole Christian World, since it drew after it very many people. In 325 the First Ecumenical Council was called against this teaching, and at this council 318 of the chief hierarchs of the church unanimously expressed the ancient teaching of Orthodoxy and condemned the false teaching of Arius. The Council triumphantly pronounced anathema against those who say that there was a time the Son of God did not exist, against those who affirm that he was created, or that he is of a different essence from God the Father. The Council composed of a Symbol of Faith, which was confirmed and completed later at the Second Ecumenical Council. The unity and equality of honor of the Son of God with God the Father was expressed by this Council in the Symbol of Faith by their words: 'of One Essence with the Father.'" [1]

- ^ Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky pages 92–95: "After the council, the Arian heresy was divided into three branches and continued to exist from some decades. It was subject to further refutation in its details at several local councils and in the works of the great Fathers of the Church of the 4th century and part of the 5th century (Sts. Athanasius the Great, Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nyssa, Epiphanius, Ambrose of Milan, Cyril of Alexandria, and others). [2]

- ^ Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary: The Ecumenical Councils

- ^ http://www.religion-encyclopedia.com/A/arius.htm

- ^ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Alexander (of Alexandria)

- ^ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Arius

- ^ A General History of the Catholic Church: From the Commencement of the Christian Era to the...by Joseph Epiphane Darras, Charles Ignatius White, Martin John Spalding pg 500 [3]

- ^ Atrocity statistics from the Roman Era

- ^ Ecumenical, from Koine Greek oikoumenikos, literally meaning worldwide but generally assumed to be limited to the Roman Empire as in Augustus' claim to be ruler of the oikoumene/world; the earliest extant uses of the term for a council are Eusebius' Life of Constantine 3.6 [4] around 338 "σύνοδον οἰκουμενικὴν συνεκρότει" (he convoked an Ecumenical council), Athanasius' Ad Afros Epistola Synodica in 369 [5], and the Letter in 382 to Pope Damasus I and the Latin bishops from the First Council of Constantinople[6]

- ^ a b c Richard Kieckhefer (1989). "Papacy". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-684-18275-0

- ^ canon 6

- ^ canon 7

- ^ a b c "Arianism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Armenian Church Library: Nicene Creed

- ^ "Nicene Creed." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c "Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Apollinarius." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ La Due, William J., "The Chair of Saint Peter", pp. 300–301, Orbis Books (Maryknoll, NY; 1999)

- ^ Athanasius, On the Incarnation 47

- ^ Pope Vigilius, Constitution of Pope Vigilius, 553

- ^ "St John Chrysostom" in the Catholic Encyclopedia, available online; retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Walter Laqueur, The Changing Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times To The Present Day, (Oxford University Press: 2006), p.48. ISBN 0-19-530429-2. 48

- ^ Yohanan (Hans) Lewy, "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0), Ed. Cecil Roth (Keter Publishing House: 1997). ISBN 965-07-0665-8.

- ^ Known in Latin and Low Franconian as Ambrosius, in Italian as Ambrogio and in Lombard as Ambroeus.

- ^ One may hear Orthodox monks referred to as "Basilian Monks," but this is really an inappropriate application of western categories to Orthodoxy.

- ^ McDonald & Sanders, The Canon Debate, pages 414–415, for the entire paragraph

- ^