- Labarum

-

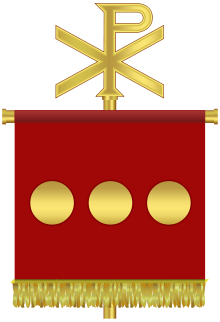

The labarum (Greek: λάβαρον) was a vexillum (military standard) that displayed the "Chi-Rho" symbol ☧, formed from the first two Greek letters of the word "Christ" (Greek: ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ, or Χριστός) — Chi (χ) and Rho (ρ).[1] It was used by the Roman emperor Constantine I. Since the vexillum consisted of a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was ideally suited to symbolize the crucifixion of Christ.

The etymology of the word labarum is unclear;[2] it is perhaps to be derived from Latin /labāre/ 'to totter, to waver' (in the sense of the "waving" of a flag in the breeze). Other proposals include a derivation from Celtic llafar ("eloquent"), from the Latin laureum [vexillum] ("laurel standard")[3] or from ancient Cantabri dialect labaro ('four heads') (in modern-day Basque the word is lauburu, with the same meaning), an ancient celtic symbol taken by the Legions during the Cantabrian Wars.

Later usage has sometimes regarded the terms "labarum" and "Chi-Rho" as synonyms. Ancient sources, however, draw an unambiguous distinction between the two.

Contents

Vision of Constantine

On the evening of October 27, 312, with his army preparing for the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the emperor Constantine I claimed to have had a vision which led him to fight under the protection of the Christian God.

Lactantius states[4] that, in the night before the battle, Constantine was commanded in a dream to "delineate the heavenly sign on the shields of his soldiers". He obeyed and marked the shields with a sign "denoting Christ". Lactantius describes that sign as a "staurogram", or a Latin cross with its upper end rounded in a P-like fashion, rather than the better known Chi-Rho sign described by Eusebius of Caesarea. Thus, it had both the form of a cross and the monogram of Christ's name from the formed letters "X" and "P", the first letters of Christ's name in Greek.

From Eusebius, two accounts of the battle survive. The first, shorter one in the Ecclesiastical History leaves no doubt that God helped Constantine but doesn't mention any vision. In his later Life of Constantine, Eusebius gives a detailed account of a vision and stresses that he had heard the story from the emperor himself. According to this version, Constantine with his army was marching somewhere (Eusebius doesn't specify the actual location of the event, but it clearly isn't in the camp at Rome) when he looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek words Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα. The Latin translation of the Greek is in hoc signo vinces— literally "In this sign, win," a more useful English translation would be, "By this sign conquer." At first he was unsure of the meaning of the apparition, but the following night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use the sign against his enemies. Eusebius then continues to describe the labarum, the military standard used by Constantine in his later wars against Licinius, showing the Chi-Rho sign.[5]

Those two accounts can hardly be reconciled with each other, though they have been merged in popular notion into Constantine seeing the Chi-Rho sign on the evening before the battle. Both authors agree that the sign was not readily understandable as denoting Christ, which corresponds with the fact that there is no certain evidence of the use of the letters chi and rho as a Christian sign before Constantine. Its first appearance is on a Constantinian silver coin from c. 317, which proves that Constantine did use the sign at that time, though not very prominently.[6] He made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum only later in the conflict with Licinius.

The vision has been interpreted in a solar context (e.g. as a solar halo phenomenon), which would have been reshaped to fit with the Christian beliefs of the later Constantine.

Eusebius' description of the labarum

"A Description of the Standard of the Cross, which the Romans now call the Labarum." "Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it. On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and within this, the symbol of the Saviour’s name, two letters indicating the name of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, of the pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner."

"The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it should be carried at the head of all his armies."[7]

Iconographic career under Constantine

The emperor Honorius holding a variant of the labarum - the Latin phrase on the cloth means "In the name of Christ [rendered by the Greek letters XPI] be ever victorious."

The emperor Honorius holding a variant of the labarum - the Latin phrase on the cloth means "In the name of Christ [rendered by the Greek letters XPI] be ever victorious."

Among a number of standards depicted on the Arch of Constantine, which was erected, largely with fragments from older monuments, just three years after the battle, the labarum does not appear. A grand opportunity for just the kind of political propaganda that the Arch otherwise was expressly built to present was missed. That is if Eusebius' oath-confirmed account of Constantine's sudden, vision-induced, conversion can be trusted. Many historians have argued that in the early years after the battle the emperor had not yet decided to give clear public support to Christianity, whether from a lack of personal faith or because of fear of religious friction. The arch's inscription does say that the Emperor had saved the res publica INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS MENTIS MAGNITVDINE ("by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse] of divinity"). As with his predecessors, sun symbolism – interpreted as representing Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun) or Helios, Apollo or Mithras – is inscribed on his coinage, but in 325 and thereafter the coinage ceases to be explicitly pagan, and Sol Invictus disappears. In his Historia Ecclesiae Eusebius further reports that, after his victorious entry into Rome, Constantine had a statue of himself erected, "holding the sign of the Savior [the cross] in his right hand." There are no other reports to confirm such a monument.

Whether Constantine was the first Christian emperor supporting during his rule a peaceful transition to Christianity, or an undecided pagan believer until middle age, strongly influenced in his political-religious decisions by his Christian mother St. Helena, is still in dispute among historians.

As for the labarum itself, there is little evidence for its use before 317.[8] In the course of Constantine's second war against Licinius in 324, the latter developed a superstitious dread of Constantine's standard. During the attack of Constantine's troops at the Battle of Adrianople the guard of the labarum standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers seemed to be faltering. The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to embolden Constantine's troops and dismay those of Licinius.[9] At the final battle of the war, the Battle of Chrysopolis, Licinius, though prominently displaying the images of Rome's pagan pantheon on his own battle line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at it directly.[10]

Constantine felt that both Licinius and Arius were agents of Satan, and associated them with the serpent described in the Book of Revelation (12:9).[11] Constantine represented Licinius as a snake on his coins.[12]

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine, other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of Vetranio (illustrated) dating from 350.

Later usage

The emperor Constantine Monomachos (centre panel of a Byzantine enamelled crown) holding a miniature labarum

A later Byzantine manuscript indicates that a jewelled labarum standard believed to have been that of Constantine was preserved for centuries, as an object of great veneration, in the imperial treasury at Constantinople.[13] The labarum, with minor variations in its form, was widely used by the Christian Roman emperors who followed Constantine I.

A miniature version of the labarum became part of the imperial regalia of Byzantine rulers, who were often depicted carrying it in their right hands.

The term "labarum" is used generally for any ecclesiastical banner, such as those carried in religious processions.

"The Holy Lavaro" were a set of early national Greek flags, blessed by the Greek Orthodox Church. Under these banners the Greeks united throughout the Greek Revolution (1821), a war of liberation waged against the Ottoman Empire.

Labarum also gives its name (Labaro) to a suburb of Rome adjacent to Prima Porta, one of the sites where the 'Vision of Constantine' is placed by tradition.

See also

- Battle of Adrianople (324)

- Battle of Chrysopolis

- Labrys

- Christian symbolism

- Christogram

- Constantine I and Christianity

- Cantabrian Labarum

- Ammianus Marcellinus

- Arch of Constantine, triumphal arch to the victory at Milvian Bridge.

- Christianity

- Constantinian shift

- Chi Rho

- Michaelion

- XI monogram

Notes

- ^ In Unicode, the Chi-Rho symbol is encoded at U+2627 (☧), and for Coptic at U+2CE9 (⳩).

- ^ Nevertheless, see H. Grégoire, "L'étymologie de 'Labarum'" Byzantion 4 (1929:477-82).

- ^ Kazhdan, p. 1167

- ^ Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors, chapter 44.5.

- ^ Gerberding and Moran Cruz, 55; cf. Eusebius, Life of Constantine.

- ^ Smith, 104: "What little evidence exists suggests that in fact the labarum bearing the chi-rho symbol was not used before 317, when Crispus became Caesar..."

- ^ Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, Chapter XXXI.

- ^ Smith, JH, p. 104: "What little evidence exists suggests that in fact the labarum bearing the chi-rho symbol was not used before 317, when Crispus became Caesar..."

- ^ Odahl, p. 178

- ^ Odahl, p.180

- ^ Constantine and the Christian empire by Charles Matson Odahl 2004 ISBN 0415174856 page 315

- ^ A Companion to Roman Religion by Jörg Rüpke 2011 ISBN 1444339249 page 159

- ^ Lieu and Montserrat p. 118. From a Byzantine life of Constantine (BHG 364) written in the mid to late ninth century.

Further reading

- Grabar, Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton University Press) 1968:165ff

- Grant, Michael (1993), The Emperor Constantine, London. ISBN 0-75380-5286

- R. Grosse, "Labarum", Realencyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft vol. 12, pt 1(Stuttgart) 1924:240-42.

- H. Grégoire, "L'étymologie de 'Labarum'" Byzantion 4 (1929:477-82).

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, p. 1167, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- A. Lipinsky, "Labarum" Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie 3 (Rome:1970)

- Lieu, S.N.C and Montserrat, D. (Ed.s) (1996), From Constantine to Julian, London. ISBN 0-415-09336-8

- Odahl, C.M., (2004) Constantine and the Christian Empire, Routledge 2004. ISBN 0415174856

- Smith, J.H., (1971) Constantine the Great, Hamilton, ISBN 0684123916

Categories:- Christian symbols

- Christian iconography

- 4th-century Christianity

- Constantine the Great and Christianity

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.