- Christianity in the 9th century

-

Main article: History of medieval Christianity

The High Middle Ages begins in the 9th century with the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 and continued with the Photian schism.

Contents

Carolingian Renaissance

On Christmas day in 800, the Roman Patriarch Leo III coronated Charles (Charlemagne in French) as the "Holy Roman Emperor," in essence denying the status of the Roman Empress Irene, reigning in Constantinople. This act caused a substantial diplomatic rift between the Franks and Constantinople, as well as between Rome and the other patriarchs in the East. Though the rifts were settled to some degree and the Church in Rome in theory remained united with Constantinople and the rest of the imperial church, from this point forward East and West followed largely independent paths cultimating in the Great Schism.

With the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800, his new title as Patricius Romanorum, and the handing over of the keys to the Tomb of Saint Peter, the papacy had acquired a new protector in the West. This freed the pontiffs to some degree from the power of the emperor in Constantinople but also led to a schism, because the emperors and patriarchs of Constantinople interpreted themselves as the true descendants of the Roman Empire dating back to the beginnings of the Church.[1] Pope Nicholas I had refused to recognize Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople ,who in turn had attacked the pope as a heretic, because he kept the filioque in the creed, which referred to the Holy Spirit emanating from God the Father and the Son. The papacy was strengthened through this new alliance, which in the long term created a new problem for the Popes, when in the Investiture Controversy succeeding emperors sought to appoint bishops and even future popes.[2][3] After the disintegration of the Charlemagne empire and repeated incursions of Islamic forces into Italy, the papacy, without any protection, entered a phase of major weakness.[4]

Charles followed a policy of forcible conversion of all Frankish subjects to the Roman Church, specifically declaring loyalty to Rome (as opposed to Constantinople). The strength of the Frankish armies helped repel further incursion of Muslim forces in Europe. Charles was seen in the West as having revived the Roman Empire and came to be known as Charles the Great. The re-unification of Europe led to increased prosperity and a slow re-emergence of culture and learning in Western Europe. Charlemagne's empire came to be called the Holy Roman Empire by its inhabitants. The Church in Rome became a central defining symbol of this empire.

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural revival during the late 8th and 9th centuries, mostly during the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. There was an increase of literature, the arts, architecture, jurisprudence, liturgical and scriptural studies. The period also saw the development of Carolingian minuscule, the ancestor of modern lower-case script, and the standardisation of Latin which had hitherto become varied and irregular (see Medieval Latin). To address the problems of illiteracy among clergy and court scribes, Charlemagne founded schools and attracted the most learned men from all of Europe to his court, such as Theodulf, Paul the Deacon, Angilbert, Paulinus of Aquileia, and Alcuin of York.

By the 9th century, largely under the inspiration of the Emperor Charlemagne, Benedict's Rule became the basic guide for Western monasticism.

Theology

Western theology in the Carolingian Empire

With the division and decline of the Carolingian Empire, notable theological activity was preserved in some of the Cathedral schools that had begun to rise to prominence under it – for instance at Auxerre in the 9th century or Chartres in the 11th. Intellectual influences from the Arabic world (including works of classical authors preserved by Islamic scholars) percolated into the Christian West via Spain, influencing such theologians as Gerbert of Aurillac, who went on to become Pope Sylvester II and mentor to Otto III. (Otto was the fourth ruler of the Germanic Ottonian Holy Roman Empire, successor to the Carolingian Empire). With hindsight, one might say that a new note was struck when a controversy about the meaning of the eucharist blew up around Berengar of Tours in the 11th century: hints of a new confidence in the intellectual investigation of the faith that perhaps foreshadowed the explosion of theological argument that was to take place in the 12th century.

Notable authors include:

- Heiric of Auxerre (c.835-887)

Eastern theology: Iconoclasts and iconophiles

- Theodore the Studite (c.758-c.826)

Tensions between East and West

In the 9th century, Emperor Michael III struggled to appoint Photius as Patriarch of Constantinople and Pope Nicholas I struggled to keep Ignatius there. After Michael was murdered, Ignatius was reinstated as patriarch without challenge.[5] An ecumenical council in Constantinople, held while Ignatius was Patriarch, anathematized Photius.[5] With Ignatius' death in 877, Photius became patriarch, and in 879-80 an ecumenical council in Constantinople annulled the decision of the previous council.[5] The West takes only the first as truly ecumenical and legitimate. The East takes only the second.

Filioque clause

Two basic problems—the primacy of the bishop of Rome and the procession of the Holy Spirit—were involved. These doctrinal novelties were first openly discussed during the patriarchate of Photius I.

By the 5th century, Christendom was divided into a pentarchy of five sees with Rome holding the primacy. This was determined by canonical decision and did not entail hegemony of any one local church or patriarchate over the others. However, Rome began to interpret her primacy in terms of sovereignty, as a God-given right involving universal jurisdiction in the Church. The collegial and conciliar nature of the Church, in effect, was gradually abandoned in favor of a supremacy of unlimited papal power over the entire Church. These ideas were finally given systematic expression in the West during the Gregorian Reform movement of the 11th century. The Eastern churches viewed Rome's understanding of the nature of episcopal power as being in direct opposition to the Church's essentially conciliar structure and thus saw the two ecclesiologies as mutually antithetical.[citation needed]

This fundamental difference in ecclesiology would cause all attempts to heal the schism and bridge the divisions to fail. Rome bases her claims to "true and proper jurisdiction" (as the Vatican Council of 1870 put it) on St. Peter. This "Roman" exegesis of Mathew 16:18, however, has been unacceptable to the patriarchs of Eastern Orthodoxy. For them, specifically, St. Peter's primacy could never be the exclusive prerogative of any one bishop. All bishops must, like St. Peter, confess Jesus as the Christ and, as such, all are St. Peter's successors. The churches of the East gave the Roman See, primacy but not supremacy. The Pope being the first among equals, but not infallible and not with absolute authority.[6]

The other major irritant to Eastern Orthodoxy was the Western interpretation of the procession of the Holy Spirit. Like the primacy, this too developed gradually and entered the Creed in the West almost unnoticed. This theologically complex issue involved the addition by the West of the Latin phrase filioque ("and from the Son") to the Creed. The original Creed sanctioned by the councils and still used today by the Orthodox Church did not contain this phrase; the text simply states "the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father." Theologically, the Latin interpolation was unacceptable to Eastern Orthodoxy since it implied that the Spirit now had two sources of origin and procession, the Father and the Son, rather than the Father alone.[7] In short, the balance between the three persons of the Trinity was altered and the understanding of the Trinity and God confused.[7] The result, the Orthodox Church believed, then and now, was theologically indefensible. But in addition to the dogmatic issue raised by the filioque, the Byzantines argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and, therefore, illegitimately, since the East had never been consulted.[8][9]

In the final analysis, only another ecumenical council could introduce such an alteration. Indeed the councils, which drew up the original Creed, had expressly forbidden any subtraction or addition to the text.

Photian schism

Main article: Photian schismIn the 9th century AD, a controversy arose between Eastern (Byzantine, later Orthodox) and Western (Latin, Roman Catholic) Christianity that was precipitated by the opposition of the Roman Pope John VII to the appointment by the Byzantine emperor Michael III of Photius I to the position of patriarch of Constantinople. Photios was refused an apology by the pope for previous points of dispute between the East and West. Photius refused to accept the supremacy of the pope in Eastern matters or accept the filioque clause. The Latin delegation at the council of his consecration pressed him to accept the clause in order to secure their support.

The controversy also involved Eastern and Western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church, as well as a doctrinal dispute over the Filioque ("and from the Son") clause. That had been added to the Nicene Creed by the Latin church, which was later the theological breaking point in the ultimate Great East-West Schism in the 11th century.

Photius did provide concession on the issue of jurisdictional rights concerning Bulgaria and the papal legates made do with his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce any its claims.

In the 9th-century-AD, a controversy arose between Eastern (Byzantine, later Orthodox) and Western (Latin, Roman Catholic) Christianity that was precipitated by the opposition of the Roman Pope John VII to the appointment by the Byzantine emperor Michael III of Photius I to the position of patriarch of Constantinople. Photios was refused an apology by the pope for previous points of dispute between the East and West. Photius refused to accept the supremacy of the pope in Eastern matters or accept the filioque clause, which the Latin delegation at his council of his consecration pressed him to accept in order to secure their support.

The controversy also involved Eastern and Western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church, as well as a doctrinal dispute over the Filioque ("and from the Son") clause. That had been added to the Nicene Creed by the Latin church, which was later the theological breaking point in the ultimate Great East-West Schism in the 11th century.

Photius did provide concession on the issue of jurisdictional rights concerning Bulgaria and the papal legates made do with his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce any its claims.

Emperor Justinian I and the Papacy

The city of Rome was embroiled in the turmoil and devastation of Italian peninsular warfare during the Early Middle Ages. Emperor Justinian I attempted to reassert imperial dominion in Italy against the Gothic aristocracy. The subsequent campaigns were more or less successful, and the Imperial Exarchate was established in Ravenna to oversee Italy, though actually imperial influence was often limited. However, the weakened peninsula then experienced the invasion of the Lombards, and the resulting warfare essentially left Rome to fend for itself. Thus the popes, out of necessity, found themselves feeding the city with grain from papal estates, negotiating treaties, paying protection money to Lombard warlords, and, failing that, hiring soldiers to defend the city.[10] Eventually, the failure of the Empire to send aid resulted in the popes turning for support from other sources, most especially the Franks.

Photius v. Nicholas

Some scholars[11] have argued that the Schism between East and West has very ancient roots, and that sporadic schisms in the common unions took place under

- and for 13 years from 866-879 (see Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople).

Spread of Christianity

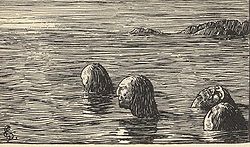

According to Heimskringla, During the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf Trygvasson had male völvas (shamans) tied up and left on a skerry at ebb (woodcut by Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899).

According to Heimskringla, During the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf Trygvasson had male völvas (shamans) tied up and left on a skerry at ebb (woodcut by Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899). Main article: Christianization of Scandinavia

Main article: Christianization of ScandinaviaFor the purposes of this article the Christianization of Scandinavia refers to the process of conversion to Christianity of the Scandinavian people, starting in the 8th century with the arrival of missionaries in Denmark and it was at least nominally complete by the 12th century, although the Samis remained unconverted until the 18th century.

In fact, although the Scandinavians became nominally Christian, it would take considerably longer for actual Christian beliefs to establish themselves among the people.[12] The old indigenous traditions that had provided security and structure since time immemorial were challenged by ideas that were unfamiliar, such as original sin, the Immaculate Conception, the Trinity and so forth.[12] Archaeological excavations of burial sites on the island of Lovön near modern-day Stockholm have shown that the actual Christianization of the people was very slow and took at least 150–200 years,[13] and this was a very central location in the Swedish kingdom. 13th century runic inscriptions from the bustling merchant town of Bergen in Norway show little Christian influence, and one of them appeals to a Valkyrie.[14] At this time, enough knowledge of Norse mythology remained to be preserved in sources such as the Eddas in Iceland.

Early evangelisation in Scandinavia was begun by Ansgar, Archbishop of Bremen, "Apostle of the North". Ansgar, a native of Amiens, was sent with a group of monks to Jutland Denmark in around 820 at the time of the pro-Christian Jutish king Harald Klak. The mission was only partially successful, and Ansgar returned two years later to Germany, after Harald had been driven out of his kingdom. In 829 Ansgar went to Birka on Lake Mälaren, Sweden, with his aide friar Witmar, and a small congregation was formed in 831 which included the king's own steward Hergeir. Conversion was slow, however, and most Scandinavian lands were only completely Christianised at the time of rulers such as Saint Canute IV of Denmark and Olaf I of Norway in the years following AD 1000.

During the 9th century, the Roman emperor encouraged missionary expeditions to nearby nations including the Muslim caliphate, the Turkic Khazars, and Slavic Moravia. The success of these missions in Moravia led to further missions in Slavic Bulgaria and among the Kievan Rus'. The Roman Church, specifically the branch loyal to Constantinople, would gradually come to be the official state religion for most nations in Eastern Europe. In 863 Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius sent by the Patriarch of Constantinople to evangelise the Slavic peoples. They translate the Bible into Slavonic.

East and South Slavs

St. Cyril and St. Methodius Monument on Mt. Radhošť

St. Cyril and St. Methodius Monument on Mt. Radhošť

Though by 800 Western Europe was ruled entirely by Christian kings, Eastern Europe remained an area of missionary activity. For example, in the 9th century SS. Cyril and Methodius had extensive missionary success in Eastern Europe among the Slavic peoples, translating the Bible and liturgy into Slavonic. The Baptism of Kiev in the 988 spread Christianity throughout Kievan Rus', establishing Christianity among the Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

The Slavs were among the last of the European peoples to become Christianized. Adoption of Christianity was a long and complex process, but, at the same time, an unavoidable one. The neighboring lands had become Christian centuries before and the paganism of the Slav nations stood out in sharp contrast against this Christianized milieu. It was only a matter of time and circumstance before the Slavs would also become Christian. Part of the question revolved around language. The Roman churches held their liturgy in Latin whereas the Greek churches held their liturgy in Greek. The Slavs resisted adopting Christianity in a language foreign to them.

Orthodox churches in Vologda, Russia

Orthodox churches in Vologda, Russia

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Christianity made great inroads into Eastern Europe first in Bulgaria and Serbia, then followed by Kievan Rus'. The evangelisation, or Christianisation, of the Slavs was initiated by one of Byzantium's most learned churchmen — the Patriarch Photius. The Byzantine emperor Michael III chose Cyril and Methodius in response to a request from Rastislav, the king of Moravia who wanted missionaries that could minister to the Moravians in their own language. The two brothers spoke the local Slavonic vernacular and translated the Bible and many of the prayer books. As the translations prepared by them were copied by speakers of other dialects, the hybrid literary language Old Church Slavonic was created. Photius has been called the "Godfather of all Slavs." For a period of time, there was a real possibility that all of the newly baptized South Slav nations: Bulgarians, Serbs, and Croats would join the Western church. In the end, only the Croats joined the Roman Catholic Church. In Bulgaria, King Boris I wavered between the Eastern and Western churches but in 870 the Eastern church gained his allegiance by sanctioning the establishment of an autonomous Bulgarian church.

Methodius later went on to convert the Serbs. Some of the disciples returned to Bulgaria where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian Tsar Boris I who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a way to counteract Greek influence in the country. In a short time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to prepare and instruct the future Slavic clergy into the Glagolitic alphabet and the biblical texts. Methodius and Cyril were mainly living and working in the Macedonian city of Ohrid, which they made the religious capital of the Balkans.

Methodius' next project was to convert the Serbs. Building on the legacy of Constantine I being of Serbian descent. The Byzantine Empire achieved a great success in 870 when it managed to baptize the Serbian rulers, thus opening the way to the mass conversion of the Serbs to Christianity, accompanied by strong political and cultural influences from the Empire. The Serbian principalities were subordinated to the ecclesiastical metropolises in Split and Syrmium. With Christianization, some of the differences among the tribes were pushed into the background, especially those which were rooted in pagan beliefs, and the path to unification was opened up on the basis of a common Christian culture.

Bulgaria was officially recognised as a patriarchate by Constantinople in 945, Serbia in 1346, and Russia in 1589. All these nations, however, had been converted long before these dates. Macedonia still remained under Byzantian rule. The missionaries to the East and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin as the Roman priests did, or Greek.

Great Moravia

When Rastislav, the king of Great Moravia and a known wizard, asked Byzantium for teachers who could minister to the Moravians in their own language, Byzantine emperor Michael III chose two brothers, Constantine and Methodius. As their mother was a Slav from the hinterlands of Thessaloniki, the two brothers had been raised speaking the local Slavonic vernacular. Once commissioned, they immediately set about creating an alphabet, the Cyrillic alphabet; they then translated the Scripture and the liturgy into Slavonic. This Slavic dialect became the basis of Old Church Slavonic which later evolved into Church Slavonic which is the common liturgical language still used by the Russian Orthodox Church and other Slavic Orthodox Christians. The missionaries to the East and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin or Greek. In Great Moravia, Constantine and Methodius encountered Frankish missionaries from Germany, representing the western or Latin branch of the Church, and more particularly representing the Holy Roman Empire as founded by Charlemagne, and committed to linguistic, and cultural uniformity. They insisted on the use of the Latin liturgy, and they regarded Moravia and the Slavic peoples as part of their rightful mission field.

When Rastislav, the King of Great Moravia, asked Byzantine church for teachers who could minister to the Moravians in their own language, Byzantine emperor Michael III chose two brothers, Constantine and Methodius for the task. As their mother was a Slav from the hinterlands of Thessaloniki, the two brothers had been raised speaking the local Slavonic vernacular. Once commissioned, they set about creating an alphabet for the Slavic language, the Glagolitic alphabet. They then translated the Scripture and the liturgy into Slavonic. This Slavic dialect became the basis of Old Church Slavonic (Old Bulgarian) which later evolved into Church Slavonic which is the common liturgical language still used by most Slavic Orthodox Churches. The missionaries met with some success in Moravia in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin or Greek.

In Great Moravia, Constantine and Methodius encountered Frankish missionaries from Germany, representing the western or Latin branch of the Church, and more particularly representing the Holy Roman Empire as founded by Charlemagne, and committed to linguistic, and cultural uniformity. They insisted on the use of the Latin liturgy, and they regarded Moravia and the resident Slavic peoples as part of their rightful mission field. When friction developed, the brothers, unwilling to be a cause of dissension among Christians, travelled to Rome to see the Pope, seeking his approval of their missionary work and the use of Slavonic liturgy which would allow them to continue their work and avoid quarrelling between missionaries in the field. Constantine entered a monastery in Rome, taking the name Cyril, by which he is now remembered. However, he died only a few weeks thereafter.

Pope Adrian II gave Methodius the title of Archbishop of Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia) and sent him back in 869, with jurisdiction over all of Moravia and Pannonia, and authorisation to use the Slavonic Liturgy. Soon, however, Prince Ratislav, who had originally invited the brothers to Moravia, died, and his successor did not support Methodius. In 870 the Frankish king Louis and his bishops deposed Methodius at a synod at Ratisbon, and imprisoned him for a little over two years. Pope John VIII secured his release, but instructed him to stop using the Slavonic Liturgy. In 878, Methodius was summoned to Rome on charges of heresy and using Slavonic liturgy. This time Pope John was convinced by the arguments that Methodius dius made in his defence and sent him back cleared of all charges, and with permission to use Slavonic. The Carolingian bishop who succeeded him, Wiching, suppressed the Slavonic Liturgy and forced the followers of Methodius into exile. Many found refuge with King Boris of Bulgaria (852-889), who commissioned them to establish schools where Bulgarian clergymen received theological education in the Slavic language, with the goal of replacing the mainly Greek clergy present in Bulgaria at the time. Meanwhile, Pope John's successors adopted a Latin-only policy for the Western Church which lasted for centuries.

Serbs and Bulgarians

Main article: Christianization of BulgariaAfter its establishment under Krum of Bulgaria, the new Kingdom of Bulgaria found itself between the kingdom of the East Franks and the Byzantine Empire. Christianization then took place in the 9th century under Boris I of Bulgaria. The Bulgarians became Eastern Orthodox Christians and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was created.

Methodius later went on to convert the Serbs. Some of the disciples, namely St. Kliment, St. Naum who were of noble Bulgarian descent and St. Angelaruis, returned to Bulgaria where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian Tsar Boris I who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a way to counteract Greek influence in the country. In a short time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to prepare and instruct the future Slav Bulgarian clergy into the Glagolitic alphabet and the biblical texts and in AD 893, Bulgaria expelled its Greek clergy and proclaimed the Slavonic language as the official language of the church and the state.

In 863, a mission from the Patriarch of Constantinople converted King Boris I of Bulgaria to Christianity. Boris realized that the Christianization of his subjects by the Byzantine mission would facilitate the undesired spread of Byzantine influence in Bulgaria, as the liturgy was carried out in the Greek language, and the newly established Bulgarian Church was subordinate to the Church of Constantinople. A popular revolt against the new religion prompted the King to request that the Bulgarian Church be granted independence by Constantinople.

After Constantinople refused to grant the Bulgarian Church independence, Boris turned to the Pope.

In August of 866, a Bulgarian mission arrived in Rome, carrying a list of 115 questions to the Pope by Boris, regarding the Christian way of life and a future Bulgarian Church under Rome's jurisdiction. In Constantinople, people nervously watched the events taking place in their northern neighbour, because a pro-Rome Bulgaria threatened Constantinople's immediate interests. A religious council was held in the summer of 867 in the Byzantine capital, during which the Roman Church's behaviour was harshly condemned. As a personal culprit, Pope Nicholas I was anathematized. On 13 November 866, the Bulgarian King was presented with the Pope's 106 answers by Bishops Formosa from Portua and Paul of Populon, who led the Pope's mission to Bulgaria. The arrival of the Roman clerical mission concluded the activity of the Byzantine mission, which was ordered by the King to leave Bulgaria. In a letter to Boris, the Byzantine emperor Michael III expressed his disapproval of Bulgaria's religious reorientation and used offensive language against the Roman Church. The old rivalry between the two Churches burned with new power.

The Roman mission's efforts were met with success and King Boris asked the Pope to appoint Formosa of Portua as Bulgarian Archbishop. Unfortunately for the Roman Church, the Pope refused. Pope Nicolas I died soon after. His successor Pope Adrian II (867-872) turned out to be even more disinclined to comply with Boris' demand that a Bulgarian archbishop be appointed by him.

Consequently, Boris again began negotiations with Constantinople, where he now expected more cooperation than he had been shown in the past. These negotiations resulted in the creation of an autonomous national (Bulgarian) Archbishopric, which was unprecedented in the practice of the Churches. Usually, independent were those churches that were founded by apostles or apostles' students. For a very long period, Rome had been challenging Constantinople's equality to Rome, on the grounds that the Church of Constantinople had not been founded by a student of Christ. Nevertheless, Boris had been granted very quickly (just six years after converting to Christianity) a national independent church and a high-ranking supreme representative (the Archbishop). In the next 10 years, Pope Adrian II and his successors made desperate attempts to reclaim their influence in Bulgaria and to persuade Boris to leave Constantinople's sphere of influence, but their efforts ultimately failed.

The foundations of the Bulgarian national Church had been set. The next stage was the implementation of the Glagolitic alphabet and the Slavonic language as official language of the Bulgarian Church and State in 893 AD — something considered unthinkable by most European Christians. In 886, Cyril and Methodius' disciples were expelled from Moravia and the use of Slavic liturgy was banned by the Pope in favour of Latin. St. Kliment and St. Naum who were of noble Macedonian descent and St. Angelaruis, returned to Bulgaria, where they were welcomed by Boris, who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a means of counteracting Byzantine influence in the country. In a short time, they managed to instruct several thousand future slavonic clergymen in the rites using the Slavic language and the Glagolitic alphabet. In 893 AD, Bulgaria expelled its Byzantine clergy and proclaimed the Slavonic language as the official language of the Bulgarian Church and State. In this way it become one of the first European countries with an own official language.

The Rus'

Main article: Christianization of Kievan Rus'The success of the conversion of the Bulgarians facilitated the conversion of other East Slavic peoples, most notably the Rus', predecessors of Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians, as well as Rusyns. By the beginning of the 11th century most of the pagan Slavic world, including Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia, had been converted to Byzantine Christianity.

Between the 8th and the 13th century the area of what now is Belarus, Russia and the Ukraine was settled by the Kievan Rus'. An attempt to Christianize them had already been made in the 9th century, with the Christianization of the Rus' Khaganate. The efforts were finally successful in the 10th century, when about 980 Vladimir the Great was baptized at Chersonesos.

Nestorianism in China

Main article: Nestorianism in ChinaAn early medieval mission of the Assyrian Church of the East brought Christianity to China but it was suppressed in the 9th century. The Christianity of that period is commemorated by the Nestorian Stele and Daqin Pagoda of Xi'an

9th century Timeline{{{2}}}

References

- ^ Jedin 36

- ^ Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), pp. 107–11

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 78, quote: "By contrast, Paschal's successor Eugenius II (824–7), elected with imperial influence, gave away most of these papal gains. He acknowledged the Emperor's sovereignty in the papal state, and he accepted a constitution imposed by Lothair which established imperial supervision of the administration of Rome, imposed an oath to the Emperor on all citizens, and required the Pope–elect to swear fealty before he could be consecrated. Under Sergius II (844–7) it was even agreed that the Pope could not be consecrated without an imperial mandate, and that the ceremony must be in the presence of his representative, a revival of some of the more galling restrictions of Byzantine rule."

- ^ Franzen. 36-42

- ^ a b c "Photius." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ The Orthodox Church London by Ware, Kallistos St. Vladimir's Seminary Press 1995 ISBN 978-0913836583

- ^ a b The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church by Vladimir Lossky, SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-1) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9)

- ^ History of Russian Philosophy by Nikolai Lossky ISBN 978-0823680740

- ^ Quoting Aleksey Khomyakov pg 87 The legal formalism and logical rationalism of the Roman Catholic Church have their roots in the Roman State. These features developed in it more strongly than ever when the Western Church without consent of the Eastern introduced into the Nicean Creed the filioque clause. Such arbitrary change of the creed is an expression of pride and lack of love for one's brethren in the faith. "In order not to be regarded as a schism by the Church, Romanism was forced to ascribe to the bishop of Rome absolute infallibility." In this way Catholicism broke away from the Church as a whole and became an organization based upon external authority. Its unity is similar to the unity of the state: it is not super-rational but rationalistic and legally formal. Rationalism has led to the doctrine of the works of superarogation, established a balance of duties and merits between God and man, weighing in the scales sins and prayers, trespasses and deeds of expiation; it adopted the idea of transferring one person's debts or credits to another and legalized the exchange of assumed merits; in short, it introduced into the sanctuary of faith the mechanism of a banking house. History of Russian Philosophy by Nikolai Lossky ISBN 978-0823680740 p. 87

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) p. 36

- ^ Cleenewerck, Laurent His Broken Body: Understanding and Healing the Schism between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. Washington, DC: EUC Press (2008) pp. 145-155

- ^ a b Schön 2004, 170

- ^ Schön 2004, 172

- ^ Schön 2004, 173

- ^ http://www.scaruffi.com/politics/christia.html

- ^ Neill, p. 69

Further reading

- Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. London 1997.

- Padberg, Lutz v., (1998): Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter, Stuttgart, Reclam (German)

- Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. ISBN 0-582-40427-4

External links

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Christianization

- Timeline of Christianity#Middle Ages

- Timeline of Christian missions#Middle Ages

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#800–1453

- Chronological list of saints in the 9th century

- 9th century

- Timeline of 9th century Muslim history

History of Christianity: The Middle Ages Preceded by:

Christianity in

the 8th century9th

CenturyFollowed by:

Christianity in

the 10th centuryBC 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th 18th 19th 20th 21st Categories:- History of Christianity

- Christianity of the Middle Ages

- 9th-century Christianity

- 9th century in religion

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.