- Okinawa Prefecture

-

Okinawa Prefecture Japanese transcription(s) – Japanese 沖縄県 – Rōmaji Okinawa-ken Okinawan transcription(s) – Okinawan ウチナー県 – Rōmaji Uchinaa-ken

Symbol of Okinawa PrefectureCountry Japan Region Kyūshū Island Okinawa Capital Naha Government – Governor Hirokazu Nakaima Area – Total 2,271.30 km2 (877 sq mi) Area rank 44th Population (December 1, 2008) – Total 1,379,338 – Rank 32nd – Density 606/km2 (1,569.5/sq mi) ISO 3166 code JP-47 Districts 5 Municipalities 41 Flower Deigo (Erythrina variegata) Tree Pinus luchuensis (ryūkyūmatsu) Bird Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) Fish Banana Fish (Caesio diagramma,"Takasago", "Gurukun") Website www.pref.okinawa.jp/

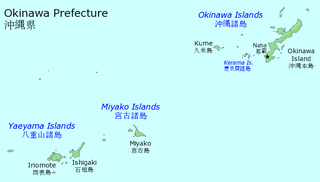

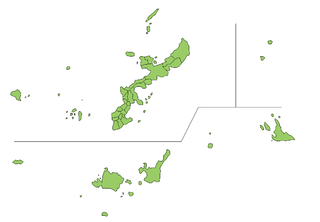

english/Okinawa Prefecture (沖縄県 Japanese: Okinawa-ken, Okinawan: Uchinaa-ken) is one of Japan's southern prefectures.[1] It consists of hundreds of the Ryukyu Islands in a chain over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) long, which extends southwest from Kyūshū (the southwesternmost of Japan's main four islands) to Taiwan. Okinawa's capital, Naha, is located in the southern part of Okinawa Island.[2] The disputed Senkaku Islands (Mandarin: Diaoyu Islands) are administered as part of Okinawa Prefecture.

Contents

History

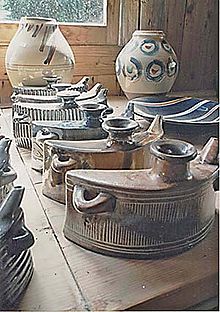

The oldest evidence of human existence in the Ryukyu islands was discovered in Naha and Yaese.[3] Some human bone fragments from the Paleolithic era were unearthed, but there is no clear evidence of Paleolithic remains. Japanese Jōmon influences are dominant in the Okinawa Islands, although clay vessels in the Sakishima Islands have a commonality with those in Taiwan.

The first mention of the word Ryukyu was written in the Book of Sui. This Ryukyu might refer to Taiwan, not the Ryukyu islands.[citation needed] Okinawa was the Japanese word depicting the islands, first seen in the biography of Jianzhen, written in 779. Agricultural societies begun in the 8th century slowly developed until the 12th century. Since the islands are located in the center of the East China Sea relatively close to Japan, China and South-East Asia, the Ryūkyū Kingdom became a prosperous trading nation. Also during this period, many Gusukus, similar to castles, were constructed. The Ryūkyū Kingdom had a tributary relationship with the Chinese Empire beginning in the 15th century.

In 1609, the Shimazu clan, which controlled the region that is now Kagoshima Prefecture, invaded the Ryūkyū Kingdom. The Ryūkyū Kingdom was obliged to agree to form a tributary relationship with the Satsuma and the Tokugawa shogunate, while maintaining its previous tributary relationship with China; Ryukyuan sovereignty was maintained since complete annexation would have created a conflict with China. The Satsuma clan earned considerable profits from trades with China during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate.

Though Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryūkyū Kingdom maintained a considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years. Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, through military incursions, officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryukyu han. At the time, the Qing Dynasty of China asserted sovereignty over the islands of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, since the Ryūkyū Kingdom was also a tributary nation of China. Ryukyu han became Okinawa Prefecture of Japan in 1879, even though all other hans had become prefectures of Japan in 1872. In 1912, Okinawans first obtained the right to vote to send representatives to the national Diet which had been established in 1890.[4]

A quarter of the civilian population died during the Battle of Okinawa.[5] After the end of World War II in 1945, Okinawa was under United States administration for 27 years. During the trusteeship rule the United States Air Force established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu islands. During the Korean War, B-29 Superfortresses flew bombing missions from Kadena AFB over Korea and China.

In 1972, the U.S. government returned the islands to Japanese administration. Under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, the United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence. 27,000 personnel, including 15,000 Marines, contingents from the Navy, Army and Air Force, and their 22,000 family members are stationed in Okinawa.[6] Since 1960, the U.S. and Japan have maintained an agreement that allows the U.S. to secretly bring nuclear weapons into Japanese ports, and there is speculation (see below) that some nuclear weapons may be located in Okinawa. Both tactical and strategic weapons have been maintained in Okinawa.[7] U.S. military bases occupied 18% of the main island and 75% of all USFJ bases are located in Okinawa prefecture.[8]

Reports by the local media of accidents and crimes committed by U.S. servicemen have reduced the local population's support for the U.S. military bases. The media has also thereby drawn new interest in the Ryukyu independence movement that developed after 1945. The rape of a 12-year-old girl by U.S. servicemen in 1995 triggered large protests in Okinawa. Partially as a result but also to deploy USFJ more efficiently, the U.S. and Japanese governments agreed in 2006 to the relocation of the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma and other minor bases. A new Japanese government that came to power in 2009 froze the relocation plan, but in April 2010 indicated their interest in resolving the issue by proposing a modified plan.[9]

Geography

Main article: Ryūkyū ShotōMajor islands

The set of islands belonging to the prefecture is called Ryūkyū Shotō (琉球諸島). Okinawa's inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄諸島 Okinawa Shotō)

- Ie-jima

- Kume

- Okinawa Island

- Kerama Islands

Cities

Okinawa Prefecture includes eleven cities. Okinawan names are in parentheses.

- Ginowan (Jinoon)

- Ishigaki (Ishigachi)

- Itoman (Ichuman)

- Miyakojima (Naaku)

- Nago (Nagu)

- Naha (Naafa) (capital)

- Nanjō (Nanjoo)

- Okinawa (Uchinaa) (formerly Koza)

- Tomigusuku (Timigushiku)

- Urasoe (Urashii)

- Uruma (Uruma)

Towns and villages

These are the towns and villages in each district.

Mergers

Geology

The island is largely composed of coral, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo[11] is an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa's main island.

Climate

The island experiences temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) for most of the year. Okinawa and the many islands that make up the prefecture contains some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world.[citation needed] Rare blue corals are found off of Ishigaki and Miyako islands as are numerous species throughout the chain.[citation needed]

Demography

Okinawa prefecture age pyramid as of October 1, 2003

(per thousands of people)Age People 0–4

84

845–9

85

8510–14

87

8715–19

94

9420–24

91

9125–29

97

9730–34

99

9935–39

87

8740–44

91

9145–49

96

9650–54

100

10055–59

64

6460–64

65

6565–69

66

6670–74

53

5375–79

37

3780 +

55

55Okinawa Prefecture age pyramid, divided by sex, as of October 1, 2003

(per thousands of people)Males Age Females 43

0–4

41

4144

5–9

41

4145

10–14

42

4248

15–19

46

4646

20–24

45

4549

25–29  48

4849

30–34

50

5043

35–39

44

4446

40–44

45

4549

45–49

47

4752

50–54  48

4832

55–59

32

3232

60–64

33

3332

65–69

34

3424

70–74  29

2914

75–79

23

2317

80 +

38

38- Source: Jinsui, Japan: Statistics Bureau (総務省 統計局), 2003, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2003np/.

Natural history

Coral reefs found in this region of Japan, provides an environment to specific fauna. The sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. The summer months carry warnings to swimmers regarding poisonous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures. Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit, and the Southeast Botanical Gardens represent tropical plant species.

Language and culture

Having historically been a separate nation until 1879, Okinawan language and culture differ in many ways from that of mainland Japan.

Language

There remain numerous Ryukyuan languages which are more-or-less incomprehensible to Japanese speakers. These languages are in decline as Standard Japanese is being used by the younger generation. Many linguists, at least those outside Japan, consider Ryukyuan languages as different languages from Japanese, while they are generally perceived as "dialects" by mainland Japanese and Okinawans themselves. Standard Japanese is almost always used in formal situations. In informal situations, de facto everyday language among Okinawans under age 60 is Okinawa-accented mainland Japanese called ウチナーヤマトグチ (Uchinaa Yamatoguchi "Okinawan Japanese"), which is often misunderstood as Okinawan language proper, ウチナーグチ (Uchinaaguchi "Okinawan language"). Uchinaaguchi is still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music, or folk dance. There is a radio news program in the language as well. [8]

Religion

Okinawa also has its own religious beliefs, generally characterized by ancestor worship and the respecting of relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods and spirits of the natural world.

Cultural influences

Okinawan culture bears traces of its various trading partners. One can find Chinese, Thai and Austronesian influences in the island's customs. Perhaps Okinawa's most famous cultural export is karate, probably a product of the close ties with and influence of China on Okinawan culture. Karate is thought to be a synthesis of Chinese kung fu with traditional Okinawan martial arts. A ban on weapons in Okinawa for two long periods after the invasion and forced annexation by Japan during the Meiji Restoration period also very likely contributed to its development.

Another traditional Okinawan product that owes its existence to Okinawa's trading history is awamori—an Okinawan distilled spirit made from indica rice imported from Thailand.

Other cultural characteristics

Other prominent examples of Okinawan culture include the sanshin—a three-stringed Okinawan instrument, closely related to the Chinese sanxian, and ancestor of the Japanese shamisen, somewhat similar to a banjo. Its body is often bound with snakeskin (from pythons, imported from elsewhere in Asia, rather than from Okinawa's venomous Trimeresurus flavoviridis, which are too small for this purpose). Okinawan culture also features the eisa dance, a traditional drumming dance. A traditional craft, the fabric named bingata, is made in workshops on the main island and elsewhere.

The Okinawan diet consist of low-fat, low-salt foods, such as fish, tofu, and seaweed. Okinawans are known for their longevity. Individuals live longer on this Japanese island than anywhere in the world. Five times as many Okinawans live to be 100 as in the rest of Japan, and the Japanese are the longest-lived nationality in the world.[12] There are 34.7 centenarians for every 100,000 inhabitants, being the highest ratio in the world.[13] The possible explanations to this fact is the diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.[13]

In recent years, Okinawan literature has been appreciated outside of the Ryūkyū archipelago. Two Okinawan writers have received the Akutagawa Prize: Matayoshi Eiki in 1995 for The Pig's Retribution (豚の報い Buta no mukui) and Medoruma Shun in 1997 for A Drop of Water (Suiteki). The prize was also won by Okinawans in 1967 by Tatsuhiro Oshiro for Cocktail Party (Kakuteru Pāti) and in 1971 by Mineo Higashi for Okinawan Boy (Okinawa no Shōnen).[14][15]

Karate

Karate originated in Okinawa. Over time, it developed into several styles and sub-styles, among them Wado Ryu, Shorin-Ryu, Uechi Ryu, Goju Ryu, Shotokan, Gohaku-Kai, Isshin-Ryu, Shito-Ryu, Shorinji Ryu, Shuri-ryū, and Pangai-noon.

Architecture

Okinawa has many remains of a unique type of castle or fortress called Gusuku. These are believed to be the predecessors of Japan's castles.[16]

Whereas most homes in Japan are made with wood and allow free-flow of air to combat humidity, typical modern homes in Okinawa are made from concrete with barred windows (protection from flying plant matter) to deal with regular typhoons. Roofs are also designed with strong winds in mind, with each tile cemented on and not merely layered as seen with many homes elsewhere in Japan.

Many roofs also display a statue resembling a lion or dragon, called a shisa, which is said to protect the home from danger. Roofs are typically red in color and are inspired by Chinese design.[16]

Okinawa during the Vietnam War

Between 1965 and 1972, Okinawa was a key staging point for the United States, in its military operations directed towards North Vietnam. Okinawa, along with Guam, also presented the United States military a geographically strategic launch pad for covert bombing missions over Cambodia and Laos.[17] Anti-Vietnam War sentiment became linked politically to the movement for reversion of Okinawa to Japan. Political leaders such as Oda Makoto, a major figure in the Beheiren movement (Foundation of Citizens for Peace in Vietnam), believed that the return of Okinawa to Japan would lead to the removal of U.S forces ending Japan's involvement in Vietnam.[18] In a speech delivered in 1967 Oda was critical of Prime Minister Sato’s unilateral support of America’s War in Vietnam claiming "Realistically we are all guilty of complicity in the Vietnam War".[18]

The United States military bases on Okinawa became a focal point for anti-Vietnam War sentiment. By 1969, over 50,000 American military personnel were stationed on Okinawa,[19] accustomed to privileges and laws not shared by the indigenous population. The United States Department of Defense began referring to Okinawa as "The Keystone of the Pacific". This idea was even stated on U.S military license plates.[20]

As controversy grew regarding the alleged placement of nuclear weapons on Okinawa, fears intensified on the possible escalation of the Vietnam War. Okinawa was then perceived, by some inside Japan, as a potential target for China, should the communist government feel threatened by the United States.[21] American military secrecy blocked any local reporting on what was actually occurring at such bases as Kadena Air Base. But as information leaked out, and images of air strikes were published, the local population began to fear the potential for retaliation.[22]

The Beheiren became a more visible protest movement on Okinawa as the American involvement in Vietnam intensified. The anti-war movement employed tactics ranging from demonstrations, to handing leaflets to soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines directly, warning of the implications for a third World War.[23] The Vietnam War forced many Okinawans to address their own recent history, in particular the destruction wrought by the battle of Okinawa in World War II. Images of devastation in Vietnam, by planes based and armed in Okinawa, led many to see parallels in the two wars. This sympathy for a fellow Asian nation only increased public outrage, and calls for a return to what Okinawans called "Absolute Pacifism".[24]

The United States military bases, once viewed as paternal post war protection, were increasingly seen as aggressive. The military build up on the island during the Cold War increased a division between local inhabitants and the American military. The Vietnam War highlighted the differences between the United States and Okinawa, but showed a commonality between the islands and mainland Japan.[25]

U.S. military controversy

Because the islands are close to China and Taiwan, the United States has large military bases on the island. The area of 14 U.S. bases are 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi), occupying 18% of the main island. Okinawa hosts about two-thirds of the 40,000 American forces in Japan. The islands account for less than one percent of Japan's total land.[8] Suburbs have grown towards and now surround two historic major bases, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma and Kadena Air Base. One third (9,852 acres (39.87 km2)) of the land used by the U.S. military is the Marine Corps Northern Training Area in the north of the island.

Between 1972 and 2009, there were 5,634 criminal offenses committed by US servicemen, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[5] Of the 290,814 crimes committed in Okinawa during the period 1972 to 2001, 1.7% were perpetrated by US Servicemen, a group that comprised 4% of the population.[26][clarification needed][further explanation needed][quantify]

In early 2008, the US secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a young girl of 12 by a marine on Okinawa. The U.S. military also imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[27] Some cited statistics that the crime rate of military personnel is consistently less than that of the general Okinawan population.[28] However, some criticized the statistics are not reliable as violence against women are especially under-reported.[29]

According to a 2007 Okinawa Times poll, 85% of Okinawans opposed the presence of the U.S. military,[30] due to noise pollution from military drills, the risk of aircraft accidents (such as one in 1959 that killed 17 people), environmental degradation,[31] and extra crowding from the number of personnel there,[32] although 73.4% of Japanese citizens appreciated the mutual security treaty with the U.S. and the presence of the USFJ.[33] In another poll conducted by the Asahi Shimbun in May 2010, 43% of the population wanted the complete closure of the U.S. bases, 42% wanted reduction and 11% wanted the maintenance of the status quo.[34] The Okinawan prefectural government and local municipalities have made various withdrawal demands of the U.S. military since the end of WWII,[35] but no fundamental solution has ever been undertaken by either the Japanese or U.S. governments.

Alleged former U.S. nuclear arms base

Japanese tended to oppose the introduction of nuclear arms into Japanese territory by the government's assertion of non-nuclear policy and a statement of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. Prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese administration in 1972, it is speculated, but never confirmed, that 1200 nuclear weapons were deployed to U.S. bases in Okinawa.[36] Most of the weapons were alleged to be stored in ammunition bunkers at Kadena Air Base.

It is widely speculated that not all the supposed weapons were removed from Okinawa.[37][38] In an interview with the Mainichi Shimbun in 1981, Edwin O. Reischauer, former U.S. ambassador to Japan, said that U.S. naval ships armed with nukes stopped at Japanese ports on a routine duty and this was approved by the Japanese government.

MCAS Futenma relocation

The governments of the United States and Japan agreed on October 26, 2005 to move the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma base from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab. Under the plan, thousands of Marines will relocate. The move is partly an attempt to relieve tensions between the people of Okinawa and the Marine Corps. Protests from environmental groups and residents over the construction of part of a runway at Camp Schwab, and from businessmen and politicians around Futenma and Henoko, have occurred.[39]

The legality of the proposed heliport relocation has been questioned as being a violation of International Law, including the World Heritage Convention, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[40][41]

Proposed solutions

As recently as 2003, the U.S. was considering moving most of the 20,000 Marines on Okinawa to new bases that would be established in Australia; increasing the presence of U.S. troops in Singapore and Malaysia; and seeking agreements to base Navy ships in Vietnamese waters and ground troops in the Philippines.[citation needed]

As of 2006, some 8,000 U.S. Marines were being removed from the island and being relocated to Guam.[42] In November 2008, U.S. Pacific Command Commander Admiral Timothy Keating stated that the move to Guam would probably not be completed before 2015.[43]

Japan's former foreign minister Katsuya Okada said he wanted to review the deployment of U.S. troops in Japan to ease the burden on the people of Okinawa, where many U.S. bases are located, the Associated Press reported October 7, 2009.

Education

The public schools in Okinawa are overseen by the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. The agency directly operates several public high schools.[44] The U.S. Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operates 13 schools total in Okinawa. Seven of these schools are located on Kadena Air Base.

Okinawa has many types of private schools. Some of them are cram schools, also known as juku. Others, such as Nova, solely teach language. People also attend small language schools.[45] Japanese language schools for foreigners are also becoming popular in Okinawa.[46]

There are 10 colleges/universities in Okinawa including the Asian Division of University of Maryland University College (UMUC). Starting in September 2012, the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology[47] – which also conducts all research and education in English and has a faculty and student body which is over half non-Japanese – will offer a PhD program in cross-disciplinary science.

Sports

Association football

Basketball

- Ryukyu Golden Kings (Naha)

In addition, various baseball teams hold training during the winter in the prefecture as it is the warmest prefecture of Japan with no snow and higher temperatures than other prefectures.

- Softbank Hawks

- Yokohama BayStars

- Chunichi Dragons

- Yakult Swallows

There are numerous golf courses in the prefecture, and there was formerly a professional tournament called the Okinawa Open.

Transportation

Air transportation

- Aguni Airport

- Hateruma Airport

- Iejima Airport

- Ishigaki Airport

- Kerama Airport

- Kita Daito Airport

- Kumejima Airport

- Minami-Daito Airport

- Miyako Airport

- Naha Airport

- Shimojijima Airport

- Tarama Airport

- Yonaguni Airport

Highways

- Okinawa Expressway

- Naha Airport Expressway

- Route 58

- Route 329

- Route 330

- Route 331

- Route 332

- Route 390

- Route 449

- Route 505

- Route 506

- Route 507

Rail

Ports

The major ports of Okinawa include:

- Naha Port[49]

- Port of Unten[50]

- Port of Kinwan[51]

- Nakagusukuwan Port[52]

- Hirara Port[53]

- Port of Ishigaki[54]

Economy

The United States has a number of bases on Okinawa which are financially supported by the U.S. and Japan. They provide jobs for Okinawans, both directly and indirectly.

United States military installations

- USMC

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- Camp Foster

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Camp Kinser

- Camp Courtney

- Camp McTureous

- Camp Hansen

- Camp Schwab

- Camp Gonsalves (Jungle Warfare Training Center)

- USAF

- USN

- Camp Lester (Camp Kuwae)[55]

- Camp Shields

- Naval Facility White Beach

- USA

- Torii Station

- Fort Buckner

- Naha Military Port

Notables

- Uechi Kanbun was the founder of Uechi-ryū, one of the primary karate styles of Okinawa.

- Mitsuru Ushijima was the Japanese general at the Battle of Okinawa, during the final stages of World War II.

- Isamu Chō was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army known for his support of ultranationalist politics and involvement in a number of attempted military and right-wing coup d'etats in pre-World War II Japan.

- Ota Minoru was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, and the final commander of the Japanese naval forces defending the Oroku Peninsula during the Battle of Okinawa.

- Sato Eisaku was a Japanese politician and the 61st, 62nd and 63rd Prime Minister of Japan. During his premier days, Okinawa was returned to Japan.

- Yabu Kentsu was a prominent teacher of Shōrin-ryū karate in Okinawa from the 1910s until the 1930s, and was among the first people to demonstrate karate in Hawaii.

- Takamine Tokumei He successfully performed surgery for the grandson of King Sho Tei, Sho Eki under general anesthesia.

- Takuji Iwasaki was a Japanese meteorologist, biologist, ethnologist historian.

- Ernest Taylor Pyle was an American journalist until his death in combat during World War II. He died in IeJima, Okinawa.

- Lieutenant-General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. was killed during the closing days of the Battle of Okinawa by enemy artillery fire, making him the highest-ranking US military officer to have been killed by enemy fire during World War II.

- Rino Nakasone Razalan professional dancer and choreographer.

- Yukie Nakama singer, musician and actress

- Namie Amuro Japanese Rhythm and blues singer

- Daichi Miura Japanese J-pop singer, dancer and choreographer.

- Matayoshi Eiki Okinawan novel writer, winner of Akutagawa prize

- Gackt Japanese J-pop/J-rock singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor and author

See also

- History of Ryukyu Islands

- Okinawa Island

- Okinawan language

- Okinawan name

- People from Okinawa Prefecture

- Okinawan Americans

- Ryukyu independence movement

- Ryukyu Islands

- Ryukyu (Okinawan) Samurai

- Ryukyuan people

- Ryukyuan religion

References

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Okinawa-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 746-747 at Google Books.

- ^ Nussbaum, "Naha" in p. 686 at Google Books.

- ^ 山下町第1洞穴出土の旧石器について(Japanese), 南島考古22

- ^ Steve Rabson, "Meiji Assimilation Policy in Okinawa: Promotion, Resistance, and "Reconstruction" in New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan (Helen Hardacre, ed.). Brill, 1997. p. 642.

- ^ a b David Hearst (March 11, 2011). "Second battle of Okinawa looms as China's naval ambition grows". The Guardian. UK. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/07/okinawa-japan-military-tension.

- ^ 沖縄県の基地の現状(Japanese), Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ^ Japanese government reveals secret nuclear agreement with the US, Chan, John., World Socialist Website retrieved March 24, 2010

- ^ a b 沖縄に所在する在日米軍施設・区域(Japanese), Japan Ministry of Defense

- ^ Pomfret, John (April 24, 2010). "Japan moves to settle dispute with U.S. over Okinawa base relocation". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/23/AR2010042305080.html.

- ^ 尖閣諸島の領有権確保及び同諸島周辺海域の海洋資源調査活動の推進に関する意見書 Okinawa Prefecture

- ^ Gyokusendo Cave

- ^ National Geographic magazine, June 1993

- ^ a b Santrock, John W. A Topical Approach to Life-Span Development. pg. 131–132. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

- ^ "Okinawa Writers Excel in Literature". The Okinawa Times (Okinawa Times). July 21, 2000. Archived from the original on August 23, 2000. http://web.archive.org/web/20000823030320/http://www.okinawatimes.co.jp/summit/english/2000/20000721_6.html. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ "芥川賞受賞者一覧" (in Japanese). Bungeishunju Ltd.. 2009. http://www.bunshun.co.jp/award/akutagawa/list1.htm. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ a b http://www.japaneselifestyle.com.au/travel/okinawa_architecture.htm

- ^ John Morrocco. Rain of Fire. (United States: Boston Publishing Company), pg 14

- ^ a b Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 120

- ^ Christopher T. Sanders (2000) America’s Overseas Garrisons the Leasehold Empire Oxford University Press PG 164

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press Pg 88

- ^ Mori, Kyozo, Two Ends of a Telescope Japanese and American Views of Okinawa, Japan Quarterly, 15:1 (1968:Jan./Mar.) p.17

- ^ ROBERT TRUMBULL, "ASIA CRISIS SLOWS OKINAWAN DRIVE :War Peril Quiets Campaign for Return to Japan." New York Times, March 10, 1965 http://0-www.proquest.com.mercury.concordia.ca/ (accessed September 27, 2009)

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 123

- ^ Tanji, Miyume., Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa (Taylor & Francis, 2006),Pg 94

- ^ ROBERT TRUMBULLSpecial to The New York Times. "OKINAWA B-52'S ANGER JAPANESE: Bombing of Vietnam From Island Stirs Public Outcry." New York Times (1857–Current file), August 1, 1965, http://0-www.proquest.com.mercury.concordia.ca/ (accessed September 27, 2009).

- ^ "Sex and Race in Okinawa". Time magazine. Time Incorporated. May 1, 2010. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1000625-4,00.html.

- ^ Justin McCurry (February 28, 2008). "Rice says sorry for US troop behaviour on Okinawa as crimes shake alliance with Japan". The Guardian. UK. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/feb/28/japan.usa.

- ^ MICHAEL HASSETT (February 26, 2008). "U.S. military crime: SOFA so good?The stats offer some surprises in wake of the latest Okinawa rape claim". The Japan Times. http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20080226zg.html.

- ^ "Okinawa: Effects of long-term US Military presence". http://www.genuinesecurity.org/partners/report/Okinawa.pdf.

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20070930160334/http://www.okinawatimes.co.jp/edi/20070513.html

- ^ Impact on the Lives of the Okinawan People (Incidents, Accidents and Environmental Issues), Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ^ 沖縄・米兵による女性への性犯罪(Rapes and murders by the U.S. military personnel 1945–2000)(Japanese), 基地・軍隊を許さない行動する女たちの会

- ^ 自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査, The Cabinet Office of Japan

- ^ http://www.asahi.com/politics/update/0513/SEB201005130037.html

- ^ Military base Affairs Division, Okinawa prefecture

- ^ 完全撤去の保証を与えよ(Japanese), Okinawa Times, October 22, 1999

- ^ "News". The Japan Times. May 15, 2002. http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20020515b9.html.

- ^ 疑惑が晴れるのはいつか(Japanese), Okinawa Times, May 16, 1999

- ^ "No home where the dugong roam". The Economist. October 27, 2005. http://www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=5097132.

- ^ Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage

- ^ "Boundary Intersections of UNESCO Heritage Conventions: Using Custom and Cultural Landscapes to Save Okinawa’s Dugong Habitat from U.S. Heliport Construction"

- ^ DefenseLink News Article: Eight Thousand U.S. Marines to Move From Okinawa to Guam

- ^ Kyodo News, "Marines' Exit May Take Till '15: U.S.", Japan Times, November 9, 2008.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Jarvie, Graeme (July 31, 2007). "'Eikaiwa' vets look beyond Big Four". The Japan Times. http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20070731zg.html. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ^ "Study and Internship Program in Okinawa, Japan". http://www.studyandinternjapan.com. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ^ http://www.oist.jp

- ^ Ryukyu Corazon

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ [7]

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/camp-kuwae.htm

External links

News

- Okinawa's Virtual Ginza, News, Information, and unique insight on Okinawa and its culture. (Updated frequently)

- Okinawa 1988–1991 Blog, reporting news about Okinawa.

- Okinawa plants

- Okinawa marine life

- Okinawa News and Ads Keeping people together and informed

Photographs

- Okinawa pictures Pictures of Okinawa Japan shot as HDR photography by Okinawa Living Magazine's Art Director.

- Wonder Okinawa

- Okinawa Japan Pictures Okinawa Japan photography group

Culture

- Ryukyu Cultural Archives

- Okinawa Prefecture Official Home-page

- The Okinawa Centenarian Study

- Okinawa Web Radio(BRAZIL)

History

- History and Photos from the United States Administration Period 1945 to 1972

- Images of Okinawa after World War II color slides were taken between 1945 and 1946

Miscellany

- Internships & Japanese language school in Okinawa

- The Contemporary Okinawa Website – History, culture, news, book reviews, historical documents, links, opinions

- Okinawa Geocaching – site for geocaching (treasure hunt with GPS) in Okinawa.

- Call of Duty game – Okinawa is featured in the video game Call of Duty: World at War

Peace

- Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

- Okinawa Peace Network of Los Angeles – Useful information on the U.S. military base controversy.

Okinawa Prefecture

Okinawa PrefectureCities

Districts Regions and administrative divisions of  Japan

JapanRegions

Prefectures Hokkaido Tōhoku Kantō Chūbu Kansai Chūgoku Shikoku Kyushu Categories:- Okinawa Prefecture

- Kyūshū region

- Ryukyu Islands

- Former regions and territories of the United States

- Prefectures of Japan

- Japan–United States relations

- Blue Zones

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄諸島 Okinawa Shotō)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.