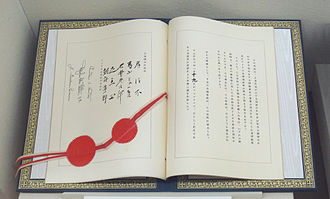

- Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan

-

United States-Japan Security Treaty Type Military Alliance Signed 19 January, 1960 Location Washington, D.C. Effective 19 May, 1960 Parties  USA,

USA,  Japan

JapanLanguage English  Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America at Wikisource

Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America at WikisourceThe Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (日本国とアメリカ合衆国との間の相互協力及び安全保障条約 Nippon-koku to Amerika-gasshūkoku to no Aida no Sōgo Kyōryoku oyobi Anzen Hoshō Jōyaku) was signed between the United States and Japan in Washington, D.C. on January 19, 1960. It strengthened Japan's ties to the West during the Cold War era. The treaty also included general provisions on the further development of international cooperation and on improved future economic cooperation.

Contents

Specifics

US military bases in Okinawa Prefecture

US military bases in Okinawa Prefecture

The earlier Security Treaty of 1951 provided the initial basis for the Japan's security relations with the United States. It was signed after Japan gained full sovereignty at the end of the allied occupation.

Bilateral talks on revising the 1951 security pact began in 1959, and the new Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security was signed in Washington on January 19, 1960. When the pact was submitted to the Diet for ratification on February 5, it became the subject of bitter debate over the Japan-United States relationship and the occasion for violence in an all-out effort by the leftist opposition to prevent its passage. It was finally approved by the House of Representatives on May 20. Japan Socialist Party deputies boycotted the lower house session and tried to prevent the LDP deputies from entering the chamber; they were forcibly removed by the police. Massive demonstrations and rioting by students and trade unions followed. These outbursts prevented a scheduled visit to Japan by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and precipitated the resignation of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, but not before the treaty was passed by default on June 19, when the House of Councillors failed to vote on the issue within the required thirty days after lower house approval.

Under the treaty, both parties assumed an obligation to maintain and develop their capacities to resist armed attack in common and to assist each other in case of armed attack on territories under Japanese administration. It was understood, however, that Japan could not come to the defense of the United States because it was constitutionally forbidden to send armed forces overseas (Article 9). In particular, the constitution forbids the maintenance of "land, sea, and air forces." It also expresses the Japanese people's renunciation of "the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes". The scope of the new treaty did not extend to the Ryukyu Islands, but an appended minute made clear that in case of an armed attack on the islands, both governments would consult and take appropriate action. Unlike the 1951 security pact, the new treaty provided for a ten-year term, after which it could be revoked upon one year's notice by either party.

Article 6 of the treaty contains a Status of Forces Agreement on the stationing of United States forces in Japan, with specifics on the provision of facilities and areas for their use and on the administration of Japanese citizens employed in the facilities. The Agreed Minutes to the treaty specified that the Japanese government must be consulted prior to major changes in United States force deployment in Japan or to the use of Japanese bases for combat operations other than in defense of Japan itself. Also covered are the limits of the two countries' jurisdictions over crimes committed in Japan by United States military personnel.

The Mutual Security Assistance Pact of 1954 initially involved a military aid program that provided for Japan's acquisition of funds, matériel, and services for the nation's essential defense. Although Japan no longer received any aid from the United States by the 1960s, the agreement continued to serve as the basis for purchase and licensing agreements ensuring interoperability of the two nations' weapons and for the release of classified data to Japan, including both international intelligence reports and classified technical information.

Opposition movement

In Japan, the treaty is known as anpo joyaku (安保条約, a contraction of 安全保障条約 anzenhoshō jōyaku) or nichibei anpo jōyaku (日米安保条約), and the student movements in the 1960s and 1970s who opposed it were known as anpo hantai.[1]

A central issue in the debate over the continued US military presence is the concentration of troops on the small Japanese prefecture of Okinawa. Nearly 75 percent of the US Forces Japan including 45,000 service members and DOD civilians, and 44,000 plus military dependents are located in Okinawa, which makes up less than one percent of Japan’s landmass (Packard, 2010). The US military bases cover about one-fifth of Okinawa* (Sumida, 2009). This has left many Okinawans feeling that while the security agreement may be beneficial to the United States and Japan as a whole, it is burdensome on the residents of the small subtropical island.

Another contentious issue to many Okinawans is the noise and environmental pollution created by the US Forces Japan. Excessive noise lawsuits in 2009 filed by Okinawa’s residents against Kadena Air Base and MCAS Futenma resulted in awards of $57 million** and $1.3 million*** dollars to residents, respectively (Sumida, 2009). Also, environmental pollution is a major issue. A large portion of Okinawa’s income is from tourism, primarily from tourists coming to appreciate the islands natural beauty and the coral reef that surrounds it. However, runoff from live fire exercises is damaging the reef (JCP, 2000). The most powerful opposition in Okinawa, however, is as a result of the criminal acts committed by US service members and their dependants. The most obvious example is the 1995 kidnapping and rape of a 12 year old Okinawan girl by two Marines and a Navy Corpsman (Packard, 2010). This crime called into serious question the SOFA agreement, particularly the jurisdiction over US military members in regards to crimes committed off post. It also seemed to be a breaking point for most Okinawans. Widespread protests occurred, and then US Secretary of State William Perry worked on an agreement with the Japanese government to reduce the number of US military members on the island (Packard, 2010).

In a 2006 agreement between the Bush administration and the Japanese government, MCAS Futenma was to be relocated to the northern Okinawa city of Nago, and 8,000 Marines and their dependants were to be relocated to Guam (Packard, 2010). This agreement, however, received very little support from Okinawans and the promise to overturn it was a major factor in helping former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama being elected to office. After spending several months deliberating over where the base would move to, Hatoyama conceded to allow the original agreement to go forward and immediately resigned after stating he failed to fulfill one of his crucial promises to the Japanese people.

A final, but crucial issue, in the debate of US military presence in Okinawa is the fact that Okinawans are as a whole pacifists (JCP, 2000). Before the Japanese annexed Okinawa and its subordinate islands, it was its own independent nation with a relatively small military. After the escalation of World War 2, however, Japanese forces occupied the island and staged it as its last stand if the War turned against their favor. In the Battle of Okinawa, their deadliest battle in the last century, over 250,000 people were killed. Of those killed, nearly 150,000 were Okinawans, either civilians or conscripts forced to fight (Frank, 2010). After the war ended, Okinawans were forced to endure the US occupation that occurred as a result of Tokyo’s decisions. This left many Okinawans embittered towards the Japanese government and the US military.

Support for agreement

Despite strong Okinawan opposition to the US military presence on the island, there is also strong support for the agreement. Due to fear of a new imperialistic Japan, US forces forced Japanese lawmakers to forbid Japan to maintain more than a self-defense sized military when drafting the post-War Constitution. As a result Japan has never spent more than one percent of ts GDP on military expenditures (Englehardt, 2010). In return for allowing the US military presence in Japan, the United States agrees to help defend Japan against any foreign adversaries, such as North Korea. In addition to military support, the military presence in Okinawa contributes to the economy of Japan’s poorest prefecture. As of 2004, 8,813 locals worked on bases, in addition to numerous others who work in shops and bars where the main customer base is US service members. Altogether, the US presence accounts for about 5 percent of the Okinawan economy (Fukumura, 2007). However, since the US bases occupy 20% of the main island, and many of them are in choice locations, in effect Okinawa's economy is suffering a deadweight loss of 15% per year.[2] However, this may be lifted, since as of 2011, the US has agreed to move its military base from Okinawa to Guam following the natural disasters and nuclear issues in Japan.

See also

- Japan – United States relations

- United States Forces Japan

- National security of Japan

- Zengakuren

- 1951 Security Treaty Between the United States and Japan

References

- ^ "Tokyo in 1967", Rolling Stone, http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/story/15380740/tokyo_in_1967.

- ^ Taira, Koji (1997). 'The Okinawan Charade' Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No. 28

- Engelhart, K. (2010). "THE BATTLE FOR OKINAWA". Maclean's, 123(10), 29–30. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database on 6 August 2010.

- Frank, R. (2010). "The Pacific War's Biggest Battle". Naval History, 24(2), 56–61. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database 6 August 2010.

- Fukumura, Y. (2007). "Okinawa: Effects of Long-term US Military Presence". Retrieved from genuinesecurity.org on 6 August 2010.

- Japanese Communist Party (February 2000). Problems of U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa Japanese Communist Party".

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Japan".

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Japan".- Packard G. (2010). "The United States-Japan Security Treaty at 50". Foreign Affairs :92–103. Retrieved from: Military & Government Collection, August 2, 2010.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (27 November 2009) "Futenma Questions and Answers". Stars and Stripes.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (1 March 2009). "$57 million awarded in Kadena noise suit". Stars and Stripes.

- Sumida, Chiyomi (22 October 2009). "Japan high court hears arguments in Futenma noise pollution lawsuit". Stars and Stripes.

Categories:- 1960 in Japan

- 1960 in the United States

- 20th-century military alliances

- 21st-century military alliances

- Cold War treaties

- Japan–United States relations

- Military alliances involving Japan

- Military alliances involving the United States

- Postwar Japan

- Treaties concluded in 1960

- Treaties entered into force in 1960

- United States armed forces in Okinawa Prefecture

- United States military in Japan

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.