- Christianity in China

-

Christianity in China is a growing minority religion that comprises Protestants (Chinese: 基督教; pinyin: Jīdūjiào; literally "Christ Religion" or Chinese: 新教; pinyin: Xīn jiào; literally "New Churches"), Catholics (Chinese: 天主教; pinyin: Tiānzhǔjiào; literally "Lord of Heaven Religion"), and a small number of Orthodox Christians. Although its lineage in China is not as ancient as the institutional religions of Taoism and Mahayana Buddhism, and the social system and ideology of Confucianism, Christianity has existed in China since at least the seventh century and has gained influence over the past 200 years.[1]

The growth of the faith has been particularly significant since the loosening of restrictions on religion by the People's Republic since the 1970s. Religious practices are still often tightly controlled by government authorities. Chinese over age 18 in the PRC are permitted to be involved with officially sanctioned Christian meetings through the "China Christian Council", "Three-Self Patriotic Movement" or the "Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association".[2] Many Chinese Christians also meet in "unregistered" house church meetings. Reports of sporadic persecution against such Christians in Mainland China have caused concern among outside observers.[3]

Contents

Terminology

There are various terms used for God in the Chinese language, the most prevalent being Shangdi (上帝, literally, "Emperor (Sovereign) Above"), used commonly by Protestants and also by non-Christians, and Tianzhu (天主, literally, "Lord of Heaven"), which is most commonly favored by Catholics. Although strictly speaking 'Shen' (神) is a more amorphous and general term, like "god," "theos" or "kami," it is also widely used by Chinese Protestants. Historically, Christians have also adopted a variety of terms from the Chinese classics as referents to God, for example Ruler (主宰) and Creator (造物主)

While Christianity is referred to as 基督教 (Christ religion), the modern Chinese language typically divides Christians into three groups: believers of Protestantism Xin jiaotu (新教徒, literally "new religion followers"), believers of Catholicism Tianzhu jiaotu (天主教徒, Lord of Heaven religion followers), and believers of Orthodox Dongzheng jiaotu (東正教徒, Eastern Orthodox religion followers, but more correctly "zhengjiaotu" 正教徒, because there is only one Chinese term for both Eastern and Oriental which is "dong" 東 and simply means the east. The latter term is more correct also because Eastern Orthodox churches are not in communion with and thus differ from the Oriental Orthodox churches.)

Pre-modern history

Earliest documented period

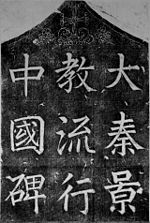

The first documented case of Christianity entering China was in the 7th century, which is known from the Nestorian Stele, a stone tablet created in the 8th century. It records that Christians reached the Tang dynasty capital Xian in 635 and were allowed to establish places of worship and to propagate their faith. The leader of the Christian travelers was Alopen.[4]

Some modern scholars argue whether Nestorianism is the proper term for the Christianity that was practiced in China, since it did not adhere to what was preached by Nestorius, and are instead preferring to refer to it as "Church of the East", a term which encompasses the various forms of early Christianity in Asia.[5]

In 845, during a time of great political and economic unrest, Emperor Wuzong decreed that Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism be banned, and their very considerable assets forfeited to the state.

In 986 a monk reported to the Patriarch of the East:

Christianity is extinct in China; the native Christians have perished in one way or another; the church has been destroyed and there is only one Christian left in the land.[6]Medieval period

The 13th century saw the Mongol-established Yuan Dynasty in China. Christianity was a major influence in the Mongol Empire, as several Mongol tribes were primarily Nestorian Christian, and many of the wives of Genghis Khan's descendants were strongly Christian. Contacts with Western Christianity also came in this time period, via envoys from the Papacy to the Mongol capital in Khanbaliq (Beijing).

Nestorianism was well established in China, as is attested by the monks Rabban Bar Sauma and Rabban Marcos, both of whom made a famous pilgrimage to the West, visiting many Nestorian communities along the way. Marcos was elected as Patriarch of the Church of the East, and Bar Sauma went as far as visiting the courts of Europe in 1287-1288, where he told Western monarchs about Christianity among the Mongols.

In 1289, Franciscan friars from Europe initiated mission work in China. For about a century they worked in parallel with the Nestorian Christians. The Franciscan mission collapsed in 1368, as the Ming Dynasty set out to eject all foreign influences.

The Chinese called Muslims, Jews, and Christians in ancient times by the same name, "Hui Hui" (Hwuy-hwuy). Crossworshipers (Christians) were called "Hwuy who abstain from animals without the cloven foot", Muslims were called "Hwuy who abstain from pork", Jews were called "Hwuy who extract the sinews". Hwuy-tsze (Hui zi) or Hwuy-hwuy (Hui Hui) is presently used almost exclusively for Muslims, but Jews were still called Lan Maou Hwuy tsze (Lan mao Hui zi) which means "Blue cap Hui zi". At Kaifeng, Jews were called "Teaou kin keaou "extract sinew religion". Jews and Muslims in China shared the same name for synagogue and mosque, which were both called "Tsing-chin sze" (Qingzhen si) "Temple of Purity and Truth", the name dated to the thirteenth century. The synagogue and mosques were also know as Le-pae sze (Libai si). A tablet indicated that Judaism was once known as "Yih-tsze-lo-nee-keaou" (israelitish religion) and synagogues known as Yih-tsze lo nee leen (Israelitish Temple), but it faded out of use.[7]

It was also reported that competition with the Roman Catholic Church and Islam were also factors in causing Nestorian Christianity to disappear in China, with "controversies with the emissaries of.... Rome, and the "progress of Mohammedanism, sapped the foundations of their ancient churches."[8] The Roman Catholics also considered the Nestorians as heretical[9]

The Ming dynasty decreed that Manichaeism and Christianity were illegal and heterodox, to be wiped out from China, while Islam and Judaism were legal and fit Confucian ideology.[10] Buddhist Sects like White Lotus were also banned by the Ming.

Post-Reformation

Above: Francis Xavier (left), Ignatius of Loyola (right) and Christ at the upper center. Below: Matteo Ricci (right) and Xu Guangqi (left), all in dialogue towards the evangelization of China.

Above: Francis Xavier (left), Ignatius of Loyola (right) and Christ at the upper center. Below: Matteo Ricci (right) and Xu Guangqi (left), all in dialogue towards the evangelization of China.

By the 16th century, there is no reliable information about any practicing Christians remaining in China. Fairly soon after the establishment of the direct European maritime contact with China (1513), and the creation of the Society of Jesus (1540), at least some Chinese become involved with the Jesuit effort. As early as 1546, two Chinese boys became enrolled into the Jesuits' St. Paul's College in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. It is one of these two Christian Chinese, known as Antonio, who accompanied St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, when he decided to start missionary work in China. However, Xavier was not able to find a way to enter the Chinese mainland, and died in 1552 on Shangchuan island off the coast of Guangdong.

It was the new regional manager ("Visitor") of the order, Alessandro Valignano, who, on his visit to Macau in 1578-1579 realized that Jesuits weren't going to get far in China without a sound grounding in the language and culture of the country. He founded St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau) and requested the Order's superiors in Goa to send a suitably talented person to Macau to start the study of Chinese.

In 1582, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, introducing Western science, mathematics, and astronomy. One of these missionaries was Matteo Ricci.

In the early 18th century, the Chinese Rites controversy, a dispute within the Roman Catholic Church, arose over whether Chinese folk religion rituals and offerings to their ancestors constituted idolatry. The Pope ultimately ruled against tolerating the continuation of these practices among Chinese Roman Catholic converts. Prior to this, the Jesuits had enjoyed considerable influence at court, but with the issuing of the papal bull, the emperor circulated edicts banning Christianity. The Catholic Church did not reverse this stance until 1939, after further investigation and a clarified ruling by Pope Pius XII.

17th to 18th centuries

Further waves of missionaries came to China in the Qing (or Manchu) dynasty (1644–1911) as a result of contact with foreign powers. Russian Orthodoxy was introduced in 1715 and Protestants began entering China in 1807.

Modern age

Missionary expansion (1807–1900)

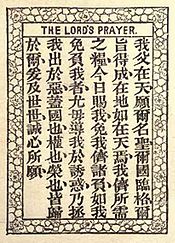

Main article: 19th Century Protestant Missions in China140 years of missionary seed-sowing began with Robert Morrison, regarded among Protestants as being the first Christian missionary to China, arriving in Macau on 4 September 1807.[11] Morrison produced a Chinese translation of the Bible. He also compiled a Chinese dictionary for the use of Westerners. The Bible translation took twelve years and the compilation of the dictionary, sixteen years.

Under the "fundamental laws" of China, one section is titled "Wizards, Witches, and all Superstitions, prohibited." The Jiaqing Emperor in 1814 A.D. added a sixth clause in this section with reference to Christianity. It was modified in 1821 and printed in 1826 by the Daoguang Emperor. It sentenced Europeans to death for spreading Christianity among Han Chinese and Manchus (tartars). Christians who would not repent their conversion were sent to Muslim cities in Xinjiang, to be given as slaves to Muslim leaders and beys.[12]

The clause stated: "People of the Western Ocean, [Europeans or Portuguese,] should they propagate in the country the religion of heaven's Lord, [name given to Christianity by the Romanists,] or clandestinely print books, or collect congregations to be preached to, and thereby deceive many people, or should any Tartars or Chinese, in their turn, propagate the doctrines and clandestinely give names, (as in baptism,) inflaming and misleading many, if proved by authentic testimony, the head or leader shall be sentenced to immediate death by strangulations : he who propagates the religion, inflaming and deceiving the people, if the number be not large, and no names be given, shall be sentenced to strangulation after a period of imprisonment. Those who are merely hearers or followers of the doctrine, if they will not repent and recant, shall be transported to the Mohammedan cities (in Turkistan) and given to be slaves to the beys and other powerful Mohammedans who are able to coerce them. . . . All civil and military officers who may fail to detect Europeans clandestinely residing in the country within their jurisdiction, and propagating their religion, thereby deceiving the multitude, shall be delivered over to the Supreme Board and be subjected to a court of inquiry."

Some hoped that the Chinese government would discriminate between Protestantism and Romanism, since the law was directed at Romanism, but after Protestant missionaries in 1835-6 gave Christian books to Chinese, the Daoguang Emperor demanded to know who were the "traitorous natives in "Canton who had supplied them with books." The foreign missionaries were strangled or expelled by the Chinese.[13]

"The Missionary herald, Volume 17" published an entry from the Peking Gazette translated by Dr. Morrison-

Ying-ho, Commander in Chief of the National Infantry, kneels to present to his majesty, the particulars of a ciise, on which he requests the Emperor's decision. The metropolis which lies immediately below the wheels of the Imperial car, being a most important region, should at all times be searched with tiie greatest strictness. I, your majesty's slave, and those associated with ine, therefore gave the most positive orders to the officers and men under the several Tartar banners, to make a very full and careful search in all those districts which pertain to them; and not to allow any person, whose circumstances and character was not perfectly plain, to lurk about. In consequence of this order, a scout, named Toomingleang found out a culprit of suspicious appearances called CMnleenching. It was discovered that this man practised the religion of the western ocean, (i. e. Europe,) and therefore he, and three others of the same religion, were seized, together with a cross, &c. which were brought before us. We, yonr Majesty's slaves, subjected them to a strict examination. Chinleenching gave the following account of himself. "I am a native of the provinoe Ganhwuy, and am now in my 4tst year. In the third year of Kea-king, (22 years ago,) I came to Peking, and lived behind the western four faced turret, on the bank, getting a livelihood by carrying burdens and shaving heads; or by being a travelling barber. I now live in a barber's shop, situated in Paoutize street; his name is Ching Kivei Knng. "During the 1st moon of the 11th year (of the late Emperor, fourteen years ago) an acquaintance, whom I had known some time, whose name was Ho, induced me to enter with him the European religion; and I then went to the Church and read prayers. In the 6th or 7th moon of that year, the European church was declared illegal, and put a stop to; and officers of government watched it, and would not let me enter; I therefore remained in the shop and read prayers. The other three persons connected with the shop, are all of the European religion. Wang-ke^o the father of Wangszevdh, came to the shop to procure hair, which was given him, and he carried it to the Foitching gate of the city. I went after him, but could not find him; and waiting till it was very late I could not get back into the city. I therefore sat down on the west side, and was there till the fourth watch, when I was seized by people connected with government; and when 1 confessed that I was of the European religion, they carried me to the shop, and apprehended the three other men, anil seized a cross, and a eatechism called yaou le wan ta, and finally they brought us all here. It was I who induced Wtmgkew to enter the European religion. The man called Ho, who induced me to adopt that religion, died long since. I real, ly have no desire to quit that religion; but only beg for mercy." Two of the other men, it was found on examination, belonged also to Gan-hwuy province, aid they received their religion from their fathers. Wangszeirih belongs to Peking, and he followed his lather Wangke-w in the profession of the European religion. They all declared they did not desire to quit the religion; but Wangkew, when examined, said he had already forsaken it. Now, the European religion is by law most rigorously forbidden; yet here, Chinleenching has audaciously presumed to keep by him a cross and a catechism; and to read prayers with these three other men: which shews a decided disregard of the laws. We apprehend that this culprit may have propagated the religion and deceived the multitude: or perhaps done something else which is crimnal; it is therefore incumbent on us to lay these circumstances before your majesty, and request your will, commanding, that all these four culprits, the cross and the eatechism be together delivered to the penal tribunal, and that the men be then subjected to a severe trial, and have their sentence determined. Reply, in the Emperor's name—"Your Report is recorded and announced."

The Missionary herald, Volume 17 then wrote the following analysis of the letter-

The phrase employed, in the above paper, for the Christum religion, or the religion of Rome, viz. Se-yang keaoxi, is one which has been of late adopted by the enemies of that religion in China, instead of the phrase employed by the Catholic Missionaries, viz. Teenchoo Anion-, which means the Religion of heaven's Lord, a designation which imports great dignity; and, even to a Chinese reader, appears venerable. It would seem that the Tartar rulers of China dread the introduction of what they choose to call (tic "European religion:" not because it differs from the ancient usages of China, nor yet because they think it false, but lest it should he connected with European politics and governments, in such a way as to affect their own domination over the Chinese. No form of Christianity is more dissimilar to the ancient opinions of China, than Buddhism oHcidia, the Tartar Shamanism, and the religion of the "yellow cap," i. e. the Thibeliau Lamanism. The shaved head, of which the above statement reminds one, and the long tail of modern times in China, are all anti-Chinese, unknown to their forefathers, and imposed on them by their Tartar conquerors on pain of death; which alternative was preferred by many of the old sons of Han, the dynasty in which the Chinese glory, and from which they take their national name. It would seem that the Tartar rulers of China dread the introduction of what they choose to call (tic "European religion:" not because it differs from the ancient usages of China, nor yet because they think it false, but lest it should he connected with European politics and governments, in such a way as to affect their own domination over the Chinese. No form of Christianity is more dissimilar to the ancient opinions of China, than Buddhism oHcidia, the Tartar Shamanism, and the religion of the "yellow cap," i. e. the Thibeliau Lamanism. If the writer of this is not mistaken, Ying-ho, the commander-in-chief has long manifested himself an officious enemy of the Christians; and, if he has not some other sinister end, )hfi bringing forward this (even according to his own shewing,) trivial case, indicates how anxious he is, that Taou-kwang, the new Emperor, should confirm the edicts of his father. The polytheism of ancient China—the worship of hills, rivers, deceased men and women, &c; the worship of living human beings; Buddhism, Shamanism, and Lamanism, as well as atheism, are all tolerated in China. The Monotheism of the Arabian Prophet, is also tolerated; why then their hatred to the name of Jesus!

The pace of missionary activity increased considerably after the First Opium War in 1842. Christian missionaries and their schools, under the protection of the Western powers, went on to play a major role in the Westernization of China in the 19th and 20th centuries.

During the 1840s, Western missionaries spread Christianity rapidly through the coastal cities that were open to foreign trade; the bloody Taiping Rebellion was connected in its origins to the influence of some missionaries on the leader Hong Xiuquan, who has since been hailed as a heretic by most Christian groups, but as a proto-communist peasant militant by the Chinese Communist Party. The Taiping Rebellion was a large-scale revolt against the authority and forces of the Qing Government. It was conducted from 1850 to 1864 by an army and civil administration led by heterodox Christian convert Hong Xiuquan. He established the "Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace" with the capital Nanjing and attained control of significant parts of southern China, at its height ruling over about 30 million people. The theocratic and militaristic regime instituted several social reforms, including strict separation of the sexes, abolition of foot binding, land socialization, suppression of private trade, and the replacement of Confucianism, Buddhism and Chinese folk religion by a form of Christianity, holding that Hong Xiuquan was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. The Taiping rebellion was eventually put down by the Qing army aided by French and British forces. With an estimated death toll of between 20 and 30 million due to warfare and resulting starvation, this civil war ranks among history's deadliest conflicts.Mao Zedong viewed the Taiping as early heroic revolutionaries against a corrupt feudal system. [15]

Christians in China established the first modern clinics and hospitals,[16] and provided the first modern training for nurses. Both Roman Catholics and Protestants founded numerous educational institutions in China from the primary to the university level. Some of the most prominent Chinese universities began as religious-founded institutions. Missionaries worked to abolish practices such as foot binding,[17] and the unjust treatment of maidservants, as well as launching charitable work and distributing food to the poor. They also opposed the opium trade[1] and brought treatment to many who were addicted. Some of the early leaders of the Chinese Republic, such as Sun Yat-sen were converts to Christianity and were influenced by its teachings.[18]

By the early 1860s the Taiping movement was almost extinct, Protestant missions at the time were confined to five coastal cities. By the end of the century, however, the picture had vastly changed. Scores of new missionary societies had been organized, and several thousand missionaries were working in all parts of China. This transformation can be traced to the Unequal Treaties which forced the Chinese government to admit Western missionaries into the interior of the country, the excitement caused by the 1859 Awakening in Britain and the example of J. Hudson Taylor (1832–1905). Taylor (Plymouth Brethren (Open Brethren)) arrived in China in 1854. Historian Kenneth Scott Latourette wrote that "Hudson Taylor was, ...one of the greatest missionaries of all time, and ... one of the four or five most influential foreigners who came to China in the nineteenth century for any purpose...". The China Inland Mission was the largest mission agency in China and it is estimated that Taylor was responsible for more people being converted to Christianity than at any other time since Paul the Apostle brought Christian teaching to Europe. Out of the 8,500 Protestant missionaries that were at one time at work in China, 1000 of them were from the CIM.[11] It was Dixon Edward Hoste, the successor to Hudson Taylor, who originally expressed the self-governing principles of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, at the time he was articulating the goal of the China Inland Mission to establish an indigenous Chinese church that was free from foreign control.

It was not always this way. Back in the era of the emperors, there were charitable organizations for virtually every social service: burial of the dead, care of orphans, provision of food for the hungry. The wealthiest in every community -- typically, the merchants -- were expected to give food, medicine, clothing, and even cash to those in need. According to Caroline Reeves, a historian at Emmanuel College in Boston, that began to change with the arrival of American missionaries in the late 19th century. "One of the reasons they gave for being there was to help the poor Chinese," she says. "Because of that need to justify their existence in China, they downplayed China's own charity. That attitude, that denial of reality, is still very strong today."[citation needed]

By 1865 when the China Inland Mission began, there were already thirty different Protestant groups at work in China,[19] however the diversity of denominations represented did not equate to more missionaries on the field. In the seven provinces in which Protestant missionaries had already been working, there were an estimated 204 million people with only 91 workers, while there were eleven other provinces in inland China with a population estimated at 197 million, for whom absolutely nothing had been attempted.[20] Besides the London Missionary Society, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, there were missionaries affiliated with Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Episcopalians, and Wesleyans. Most missionaries came from England, the United States, Sweden, France, Germany, Switzerland, or Holland.[21]

In addition to the publication and distribution of Christian literature and Bibles (see:Chinese Bible Translations), the Protestant Christian missionary movement in China furthered the dispersion of knowledge with other printed works of history and science. As the missionaries went to work among the Chinese, they established and developed schools and introduced the latest techniques in medicine[21] (see:Medical missions in China). The mission schools were viewed with some suspicion by the traditional Chinese teachers, but they differed from the norm by offering a basic education to poor Chinese, both boys and girls, who had no hope of learning at a school before the days of the Chinese Republic.[22]

The Boxer Uprising was in part a reaction against Christianity in China. Christianity was prevalent among bandits in Shandong, China. In 1895, the Manchu Yuxian, a magistrate in the province, acquired the help of the Big Swords Society in fighting against Bandits. The Big Swords practiced heterodox practices, however, they were not bandits and were not seen as bandits by Chinese authorities. The Big Swords relentlessly crushed the bandits, but the bandits converted to Catholic Christianity, because it made them legally immune to prosecution and under the protection of the foreigners. The Big Swords proceeded to attack the bandit Catholic churches and burn them.[23] Yuxian only executed several Big Sword leaders, but did not punish anyone else. More secret societies started emerging after this.[24]

In Pingyuan, the site of another insurrection and major religious disputes, the county magistrate noted that Chinese converts to Christianity were taking advantage of their bishop's power to file false lawsuits which, upon investigation, were found groundless.[25]

Popularity and indigenous growth (1900–1925)

The opening of the twentieth century was a period of transition for both the church and the nation. China moved from Qing dynastic rule to a warlord-dominated republic to a united front of the Guomindang and Chinese Communist party in league against warlords and imperialism. Variety within the Protestant community increased; conservative, evangelical societies strengthened their presence; the social gospel approach gained momentum, and Chinese formed their own faith sects and autonomous churches.

The Qing dynasty Imperial government permitted Christian missionaries to enter and proselytize in Tibetan lands, which weakened the control of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas, who refused to give alleigance to the Chinese. The Tibetan Lamas were alarmed and jealous of Catholic missionaries converting natives to Roman Catholicism. During the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion the Tibetan Buddhist Gelug Yellow Hat sect led a Tibetan revolt, with Tibetan tribesmen being led by Lamas to kill and attack Chinese officials, western Christian missionaries and native Christian converts, the revolt was aimed at expelling Christians and overthrowing Chinese rule. The Lamas responded to the Christian missionaries by massacring the missionaries and native converts to Christianity. The Lamas besieged Bat'ang, burning down the mission chapel, and killing two foreign missionaries, Père Mussot and Père Soulié. The Chinese Amban's Yamen was surrounded, the Chinese General, Wu Yi-chung, was shot dead in the Yamen by the Lama's forces. The Chinese Amban Feng and Commandant in Chief Li Chia-jui managed to escape by scattering Rupees (money) behind them, which the Tibetans proceeded to try to pick up. The Ambans reached Commandant Lo's place, but the 100 Tibetan troops serving under the Amban, armed with modern weaponry, mutinied when news of the revolt reached them. The Tibetan Lamas and their Tibetan followers besieged the Chinese Commandant Lo's palace along with local Christian converts. In the palace, they killed all Christian converts, both Chinese and Tibetan.[26]

During the Boxer Rebellion, Chinese Christians were abused by western Christians and missionaries trapped with them during the Siege of the International Legations (Boxer Rebellion). The besieging Chinese forces made peaceful overtures to the trapped westerners, the Chinese Imperial Army even sent food and supplies to the foreigners.[27] While the westerners hoarded food for themselves, champagne was flowing for them and they had access to rice, they refused to share with Chinese Christians, giving them dog meat, crows, horses and forcing them to eat bark and leaves. The westerners also enjoyed access to alcohol, and many became drunk.[28] [29] An incident occurred when Russian soldiers wanting to rape Chinese Christian schoolgirls was discovered by the British. It is unknown whether it was discovered before any rapes occurred, as sensitivity prevented an investigation.[30]

Boxers, non Christian Chinese, and Imperial Army Chinese Muslim Kansu Braves regarded Chinese Christians as traitors, acting as spies for the foreigners in the legations, when the foreign westerners began killing innocent Chinese civilians, the Boxers and Muslim troops responded by murdering any Chinese Christian they came across, some being burned alive and looting their property.[31][32]

Since missionaries contended that Western progress derived from its Christian heritage, Christianity gained new favor. The missionaries, their writings and Christian schools were accessible sources of information; parochial schools filled to overflowing. Church membership expanded and Christian movements like the YMCA and YWCA became popular. The Manchurian revival swept through the churches of present day Liaoning Province during the ministry of Canadian missionary, Jonathan Goforth. It was the first such revival to gain nationwide publicity in China as well as international repute.[33]

The number of Protestant missionaries had surpassed 8,000 by 1925 and in the process, the nature of the community had altered. Estimates for the Chinese Protestant community ranged around 500,000.

There were also growing numbers of conservative evangelicals. Some came from traditional denomination, but others worked independently with minimal support, and many were sponsored by fundamentalist and faith groups like the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Christian Missionary Alliance, and the Assemblies of God. Pentecostal, charismatic and Millenarian preachers brought a new zeal to the drive to evangelize the world.

Parochial schools also nurtured a corps of Christian leaders who acquired influential positions in education, diplomatic service and other government bureaus, medicine, business, the Christian church and Christian movements. In the Christian community, individuals like Yu Rizhang (David Yui 1882 - 1936), Zhao Zichen (趙紫宸, 1888–1979), Xu Baoqian (徐寶謙, 1892–1944), and Liu Tingfang (Timothy Liu/劉廷芳, 1890–1947) stand out. Most were characterized with liberal theology, commitment to social reform, deep Chinese patriotism, and acquaintance with Western learning. Many of these leaders held popular revival meetings in Christian schools throughout China and, along with conservative churchmen like Cheng Jingyi (1881–1939), sparked the drive for greater Chinese autonomy and leadership in the church.

They became Chinese spokesmen in the National Christian Council, a liaison committee for Protestant churches, and the Church of Christ in China (CCC), established in 1927 to work toward independence. Even so, progress toward autonomy proved to be slow, for Western mission boards were reluctant to relinquish the power of the pocket book, which gave them a decisive voice in most matters of importance.

Adding to the diversity and also to the conservative trend was the proliferation of completely autonomous Chinese Christian churches and communities, a new phenomenon in Chinese Protestantism. Noteworthy was the China Christian Independent Church (Zhōngguó Yēsūjiào Zìlìhuì), a federation which by 1920 had over 100 member churches, drawn mostly from the Chinese urban class. In contrast was the True Jesus Church (Zhēn Yēsū Jiàohuì), founded in 1917; Pentecostal, millenarian and exclusivist, it was concentrated in the central interior provinces.

Sometimes independence derived not so much from a desire to indigenize Christianity as from the nature of leadership. Wang Mingdao (1900–1991) and Song Shangjie (John Sung, 1901–1944) were zealous, confident of possessing the truth, and critical of what they perceived as lukewarm formalism in the Protestant establishments. During the 1920s and 1930s both Wang and Song worked as independent itinerant preachers, holding highly successful and emotional meetings in established churches and other venues. Their message was simple: “today’s evil world demands repentance; otherwise hell is our destiny”. To this doomsday prophecy, Song added faith healing. Their premillennial eschatology attracted tens of thousands of followers set adrift in an environment of political chaos, civil war, and personal hardship.

Era of national and social change, the Japanese occupation (1925–1949)

In the aftermath of World War I, many Westerners experienced a crisis of confidence. How could western nations, which had just emerged from one of the most destructive wars of modern times, justify preaching morality to others? Volunteers, financial and intellectual support began a steady decline. The 1929 depression soon compounded the economic troubles. Yet the difficulties accelerated indigenization.

Since many Chinese Christian leaders were internationalists and pacifists, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 presented a dilemma. Most abandoned their pacifism, and many joined the National Salvation Movement. During the Second Sino-Japanese War , Japan shortly invaded much of China and then after the Attack on Pearl Harbor the Pacific region, with the evacuation or internment of most Westerners. As a result of being separated due to World War II, Christian churches and organizations had their first experience with autonomy from the Western-guided structures of the missionary church organizations. Once again Chinese were left to carry on and once again the Chinese Protestant church moved toward independence, union, or Chinese control. Some scholars suggest this helped lay the foundation for the independent denominations and churches of the post-war period and the eventual development of the Three-Self Church and the CCPA. After the end of the war, the Chinese Civil War began in earnest, which had an effect on the rebuilding and development of the churches after the close of Japanese occupation.

The chaos that was China during the 1930s and 1940s spawned religious movements that emphasized direct spiritual experience and an eschatology offering hope and comfort beyond this cruel world. In opposition to the "Y" and the Student Christian Movement, conservatives organized the Intervarsity Christian Fellowship in 1945; for them, Social Gospel theology was not simply impotent; it had lost sight of the centrality of a personal relationship with the divine. The Jesus Family (Yēsū Jiātíng), founded about 1927, expanded in rural north and central China. Communitarian, Pentecostal, and millenarian, its family communities lived, worked and held property jointly; worship often included speaking in tongues and revelations from the Holy Spirit.

The salvationist promise of Wang Mingdao, John Sung, and Ji Zhiwen (Andrew Gih/計志文, 1901–1985) continued to attract throngs of followers, many of them already Christians. Ni Tuosheng (Watchman Nee, 1903–1972), founder of the Church Assembly Hall (nicknamed as "Little Flock"), drew adherents with its assurances of a glorious New Jerusalem in the next life for those who experienced rebirth and adhered to a strict morality. By 1945, the local churches claimed a membership of over 70,000, spread into some 700 assemblies.[34] The independent churches altogether accounted for well over 200,000 Protestants.

British and American denominations, such as the British Methodist Church, continued to send missionaries until they were prevented from doing so following the establishment of the People's Republic of China. Protestant missionaries played an extremely important role in introducing knowledge of China to the United States and the United States to China. The book The Small Woman and film Inn of the Sixth Happiness tell the story of one such missionary, Gladys Aylward.

Communist rule

The People's Republic of China was established in October 1949 by the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong. Under Communist ideology, religion was discouraged by the state and Christian Missionaries left the country in what was described by Phyllis Thompson of the China Inland Mission as a "reluctant exodus", leaving the indigenous churches to do their own administration, support, and propagation of the faith. The Chinese Protestant church entered the communist era having made significant progress toward self-support and self-government. Though Chinese rulers had traditionally sought to regulate organized religion and the CPC would continue the practice, Chinese Christians had gained experience in the art of accommodation in order to protect its members.

From 1966 to 1976 during the Cultural Revolution, the expression of religious life in China was effectively banned, including even the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. The growth of the Chinese house church movement during this period was a result of all Chinese Christian worship being driven underground for fear of persecution. To counter this growing trend of "unregistered meetings", in 1979 the government officially restored the TSPM after thirteen years of non-existence,[11] and in 1980 the CCC was formed.

In 1993 there were 7 million members of the TSPM with 11 million affiliated, as opposed to an estimated 18 million and 47 million "unregistered" Protestant Christians respectively. According to a survey done by China Partner (Founder Werner Burklin), there are now between 39-41 million Protestant Christians in China. The survey was done with 7.400 individuals in 2007-08 in all 31 provinces, municipalites and autonomous regions except Tibet. Another survey done with 4.500 individuals by the East China Normal University in Shanghai came to the same result.

Persecution of Christians in China has been sporadic. The most severe times were during the Cultural Revolution. Believers were arrested and imprisoned and sometimes tortured for their faith.[35] Bibles were destroyed, churches and homes were looted, and Christians were subjected to humiliation.[35] Several thousand Christians were known to have been imprisoned between 1983-1993.[35] In 1992 the government began a campaign to shut down all of the unregistered meetings. However, government implementation of restrictions since then has varied widely between regions of China and in many areas there is greater religious liberty.[35]

Independent churches and a variety of evangelical sects have broadened the appeal of Protestantism, especially in rural China. Although outside observers thought that the Cultural Revolution had ended Christianity in China, Christianity in all its variety had taken root and possessed the strength and techniques to survive decades of hostility and persecution.

Contemporary PRC

Since 1949, indigenous Chinese Christianity has been growing at a rate unparalleled in history.[11][36] Nicholas D. Kristof, a columnist of the New York Times wrote on June 25, 2006, "Although China bans foreign missionaries and sometimes harasses and imprisons Christians, especially in rural areas, Christianity is booming in China." [37] Most of the growth has taken place in the unofficial Chinese house church movement. Christianity also follows Chinese migration. After 2000, the center of gravity has shifted from the countryside to the cities, spreading Christianity among intellectuals and associating it with modernity, business and science.[38] In 1800 there were 250,000 baptized Roman Catholics, but no known Protestant believers out of an estimated 362 million Chinese. By 1949, out of an estimated population of 450 million, there were just over 500,000 baptized Protestant Christians.[39] Anonymous internet columnist Spengler speculated in 2007 that Christianity could "become a Sino-centric religion two generations from now."[40]

The current number of Christians in China is disputed. The most recent official census enumerated 4 million Roman Catholics and 10 million Protestants. However, independent estimates have ranged from 40 million to 130 million Christians. According to the China Aid Association, State Administration for Religious Affairs Director Ye Xiaowen reported to audiences at Beijing University and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences that the number of Christians in China had risen to 130 million by the end of 2006, including 20 million Catholics.[41][42] This has been officially denied by the Foreign Ministry.[43] According to a survey done by China Partner and East China Normal University in Shanghai, there are now 39 to 41 million Protestant Christians in China.[citation needed] These include Christians in registered and unregistered churches. All other numbers previously mentioned were rough estimates that never have been substantiated. The survey was done with 7,400 individuals in 2007-08 by China Partner in all 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions. Another survey done with 4,500 individuals by East China Normal University in Shanghai reveals up to 40 million.[citation needed] Other studies have suggested that there are roughly 54 million Christians in China, of which 39 million are Protestants and 14 million are Roman Catholics; these are seen as the most common and reliable figures.[44][45][46][47]

A Roman Catholic church by the Lancang (Mekong) River at Cizhong, Yunnan Province, China. It was built by the French missionary at the mid-19th century, but was incinerated during the anti-foreigner movement in 1905, and rebuilt Ca. 1920s. The church members are mainly Tibetans. Since the region is very ethnically diverse, they also consist of six other ethnic groups such as Han, Naxi, Lisu, Yi, Bai and Hui

A Roman Catholic church by the Lancang (Mekong) River at Cizhong, Yunnan Province, China. It was built by the French missionary at the mid-19th century, but was incinerated during the anti-foreigner movement in 1905, and rebuilt Ca. 1920s. The church members are mainly Tibetans. Since the region is very ethnically diverse, they also consist of six other ethnic groups such as Han, Naxi, Lisu, Yi, Bai and Hui

Today, the Chinese language typically divides Christians into two groups, members of Jidu jiao (literally, Christianity), Protestantism, and members of Tianzhu jiao (literally "Lord of Heaven" religion), Catholicism (see Protestantism in China and Catholicism in China.)

Official organizations

Since loosening of restrictions on religion after the 1970s, Christianity has grown significantly within the People's Republic. It is still, however, tightly controlled by government authorities. The Three-Self Patriotic Movement, China Christian Council (Protestant) and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association, which has disavowed the Pope and is considered schismatic by other Roman Catholics, have affiliations with the government and must follow the regulations imposed upon them.

House churches

Many Christians choose however to meet independently of these organizations, typically in house churches. These fellowships are not officially registered and are seen as illegal entities that are persecuted heavily, and are thus sometimes called "underground churches". These Christians have been persecuted throughout the 20th century, especially during the Cultural Revolution, and there remains some official harassment in the form of arrests and interrogations of Chinese Christians. At the same time, there has been increasing tolerance of house churches since the late 1970s.

Some informal groups have emerged in the 1970s that seem to have been wholly new in origin, or perhaps to have sprouted from earlier seeds but grown into distinctly new movements. One of the best documented of these groups was founded by Peter Xu, an independent evangelist who began preaching in Henan in 1968. his organization, variously called Born Again Movement, the Born-again Sect (重生派), the Total Scope Church (全范围教会), or the Criers, is accused by some as being heretical. It is distinguished by a strong emphasis on a definitive experience of conversion, usually during an intensive three-day "life meeting", and by an emphasis (some say a requirement) on a confession of sins with tears. Xu has claimed that his organization consists of over 3500 congregations and has sent evangelists to more than twenty of China's provinces.[citation needed] These numbers cannot be independently verified, but it is evident that there are several other organized networks claiming a similarly large number of adherents, and many other groups of smaller scope.[citation needed]

Free churches

Main article: Chinese free churchThere is a new third church movement that is growing rapidly in the urban areas of China today. Traditionally, the churches in communist China were thought to be either “Three-Self churches” (official and government-controlled churches), or “house churches” (churches meeting in homes, not part of the state). But now, there is a third church movement called the “free church” movement in China and it is gaining momentum.

Before discussing the free church movement, there is a need to explain briefly the different church movements in China since the communist revolution in 1949. When the communists systematically persecuted, and eventually outlawed the Chinese Christian church before and during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, the church went underground. As a result, the term “underground church” came into use. But after the death of Mao, the government legalized the Christian church. Then, the Christians in China began to come above ground into the officially sanctioned church, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) or the Three-Self church.

The term “Three-Self” originated with John Nevius, who was an American missionary to China and Korea in the late nineteenth century. He proposed a strategy of self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating local churches in China and Korea. The strategy took hold in Korea in the late nineteenth century, and resulted in explosive church growth in the twentieth century. However, in China, the strategy was hijacked by the communists as a tool to rid the church of “foreign influence.” The Three-Self church was officially recognized by the government in 1979, but instead of having a foreign influence, it was dominated by communism, thereby coming short of being a genuine, independent church.

When the Chinese Christians realized that communist control of the Christian church was detrimental to the spirituality and the health of the church, many of them continued to meet in homes, thus the beginning of the “house church” movement in the early 1980s. For the next three decades, these two church movements dominated the Chinese church scene. Generally, the Three-Self church is served by seminary-educated ordained ministers, whose theology is parallel to the liberal mainline churches in the US and the state churches of Europe. The house churches, however, are basically a church movement led by lay leaders in the countryside. House church members often attend the Three-Self churches on weekends to receive the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper, in addition to being part of a house church. The house churches have had explosive growth as a mainly rural church movement. Due to lack of training and discipleship, however, these churches have been plagued with the problems of heresy and cultic teachings.

A number of Three-Self pastors also often have house fellowships of their own. These pastor-led churches sometimes come into conflict with other house churches in the area. Unfortunately, many of these conflicts result in either the Three-Self churches turning the house church leaders over to the authorities for their “illegal” church activities, or the house churches categorically shunning the Three-Self churches as “apostate.” There is a real need for reconciliation among the churches in China.

More recently, some of the evangelical Three-Self pastors and the Chinese Christians who have studied at overseas seminaries have begun to plant their own independent churches in the urban areas of China such as Beijing and Shanghai. Unlike the rural house churches, which attract mostly farmers, the urban free churches tend to attract well-educated, affluent people. For example, Zion Church of Beijing is led by a former Three-Self pastor named Jin Mingri.[48][49] In addition to his education at Beijing University and Nanjing Seminary in China, he also earned a doctorate from Fuller Theological Seminary in the United States. In the spring of 2007, Jin returned to China and planted the Zion church. In less than three years, it grew to being a multisite church with close to 1,000 worshipers attending the different Sunday services. Many of the church members are scholars, officials, international businessmen, and college-educated merchants. Zion is not a house church that meets underground but an above-ground church that meets in an office building, and that refuses to either disband or register with the authorities. Despite harassment from the police, they have persevered by walking in the light rather than hiding, and by preaching the gospel boldly rather than living in fear.[50] The authorities are beginning to dialog with free churches, which could lead to official recognition.

Even with the Back to Jerusalem Movement (a movement led by house church leaders with the massive goal to send tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of Chinese missionaries to the Middle East), the kinds of training they propose (such as practicing jumping from a window in case of police crack-down or preparing for martyrdom) and the lack of international experience (such as being turned back from the border due to lack of passports), often causes house church movements to fall short. On the other hand, the next generation of Chinese church leaders and missionaries will likely come out of the free church movement in China. Their highly educated members and leaders with extensive international exposure are often backed with a vast reserve of wealth in the cities. Throughout China, there is a massive influx of the Chinese into the cities. China will be overwhelmingly urban in the next decades. This makes the urban free churches all the more important as future leaders of evangelical Christianity in China.

Orthodox Christianity

There are a small number of adherents of Russian Orthodoxy in northern China, predominantly in Harbin. The first mission was undertaken by Russians in the 17th century. Orthodox Christianity is also practiced by the small Russian ethnic minority in China. The Church operates relatively freely in Hong Kong (where the Ecumenical Patriarch has sent a metropolitan, Bishop Nikitas and the Russian Orthodox parish of St Peter and St Paul resumed its operation) and Taiwan (where archimandrite Jonah George Mourtos leads a mission church).

Religious practice

Officials from the Three-Self Patriotic Movement/China Christian Council (TSPM/CCC), the state-approved Protestant religious organization, estimated that at least twenty million citizens worship in official churches. Government officials stated that there are more than 50,000 registered TSPM churches and 18 TSPM theological schools. The Pew Research Center estimates that between 50 million and 70 million Christians practice without state sanction. The World Christian Database estimates that there are more than 300 unofficial house church networks.[51]

The Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA) reports that 5.3 million persons worship in its churches and it is estimated that there are an additional 12 million or more persons who worship in unregistered Catholic churches that do not affiliate with the CPA. According to official sources, the government-sanctioned CPA has more than 70 bishops, nearly 3,000 priests and nuns, 6,000 churches and meeting places, and 12 seminaries. There are thought to be approximately 40 bishops operating "underground," some of whom are in prison or under house arrest. During the reporting period, at least three bishops were ordained with papal approval. In September 2007 the official media reported that Liu Bainian, CPA vice president, stated that the young bishops were to be selected to serve dioceses without bishops and to replace older bishops. Of the 97 dioceses in the country, 40 reportedly did not have an acting bishop in 2007, and more than 30 bishops were over 80 years of age.[51]

On August 30, 2010, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints revealed its on-going efforts to negotiate with the Chinese authorities to regularize its activities in China. The LDS Church has had expatriate members worshiping in China for a few decades previous to this, but with many restrictions.[52]

Religious restrictions

The interior of a former Methodist church in Wuhan, converted to an upscale pastry shop with a Christianity-themed decor

The Government restricts legal religious practice to government-sanctioned organizations and registered religious groups and places of worship, and seeks to control the growth and scope of the activity of both registered and unregistered religious groups, including "house churches." Government authorities limit proselytism, particularly by foreigners and unregistered religious groups, but permit proselytism in state-approved religious venues and private settings.[51]

In 2008, the Government's repression of religious freedom intensified in some areas. Unregistered Protestant religious groups in Beijing reported intensified harassment from government authorities in the lead up to the 2008 Summer Olympic Games. Media and China-based sources reported that municipal authorities in Beijing closed some house churches or asked them to stop meeting during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. During the reporting period, officials detained and interrogated several foreigners about their religious activities and in several cases alleged that the foreigners had engaged in "illegal religious activities" and cancelled their visas. Media reported that the total number of expatriates expelled by the Government due to concerns about their religious activities exceeded one hundred.[51]

"Underground" Roman Catholic clergy faced repression, in large part due to their avowed loyalty to the Vatican, which the Government accused of interfering in the country's internal affairs. The Government continued to repress groups that it designated as "cults," which included several Christian groups.[51]

Demographics and geography

"Merry Christmas" signs (usually, in English only) are not uncommon in China during the winter holiday season, even in areas with few sign of Christian observance

It is not known exactly how many Chinese consider themselves Christian. Estimates of Christians in China are difficult to obtain because of the numbers of Christians unwilling to reveal their beliefs, the hostility of the national government towards some Christian sects, and difficulties in obtaining accurate statistics on house churches. It seems clear that the numbers are growing[53]

- In 2000, the People's Republic of China government census enumerated 4 million Chinese Catholics and 10 million Protestants.[54] The Chinese government once stated that only 1% (13 million) [55] of the population is Christian while the Chinese Embassy has stated that 10 Million (0.75%)[56] are Christian.

- The official figure in 2002, which consists of members from official Protestant churches, is about 15 million, while some estimates on members of Chinese house churches vary from 50 million to 100 million.

- In 2006 it was stated that there were 4 million members of the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association and an estimated 12 million members of the underground Roman Catholic Church in China as of 2006.[57] Kiven Choy stated, in a Chinese weekly newspaper in Hong Kong, that the correct number of Protestants in China should be at around 20 million[citation needed], while Time Magazine reported 65 million in 2006.[58]

- In October 2007 two surveys were conducted to estimate the number of Christians in China. One poll was held by Protestant missionary Werner Burklin, the other one by Liu Zhongyu from East China Normal University in Shanghai. The surveys were conducted independently and during different periods, but they reached the same results.[44][45] According to these studies, there are roughly 54 million Christians in China, of which 39 million are Protestants and 14 million are Catholics as the most common and reliable figure among others.[44][45][46]

- In 2008, the official number is 20 million in the Official Protestant churches and 10 million in the Official Catholic Church. According to China Aid Association, Ye Xiaowen, the director of the government body which supervises all religions in China, said privately that the figure was indeed as much as 130 millions in early 2008.[38] The claim was denied by Mrs. Guo Wei, director of the Foreign Affairs Department in Beijing[citation needed]. Some bloggers had attributed the report to the official Xinhua News Agency, which denied having reported anything such.[43] According to John Micklethwait "a conservative guess" (as at the end of 2008) "is that there are at least 65 million Protestants in China and 12 million Catholics"[53]

The CIA World Factbook indicates that 3%-4% of all the population in China are Christians (2002 est.).[59] Independent estimates have ranged from 40 million[55] to 100 million.[60]

A relatively large proportion of Christians are concentrated in Hebei province, in particular Catholics. Many internationally-reported arrests of Catholic leaders have occurred in that province. Hebei is also home to the town of Donglu, site of an alleged Marian apparition and pilgrimage center. Another major population is Christianity in Henan.

Hong Kong

Christianity has been in Hong Kong since 1841. Of about 670,000 Christians in Hong Kong, most of them are Protestants and Roman Catholics.

Macau

Roman Catholic missionaries were the first to arrive in Macau.[when?]

Protestants record that Tsae A-Ko was the first known Chinese Protestant Christian.[61] He was baptized by Robert Morrison at Macau about 1814.

Autonomous regions

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region

Tibet Autonomous Region

Further information: Religion in TibetXinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

Predominantly Muslim, very few Uygur are known to be Christian. In 1904, George Hunter with the CIM opened the first mission station in Xinjiang. By the 1930s there existed some churches among this people, but because of violent persecution the churches were destroyed and the believers were scattered.[62]

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

Though the Hui people live in nearly every part of China, they make up about 30% of the population of Ningxia. They are almost entirely Muslim and very few are Christian.

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region

Rapid church growth is reported to have taken place among the Zhuang people in the early 1990s.[35] Though still predominantly Buddhist and animistic, the region of Guangxi was first visited in 1877 by Protestant missionary Edward Fishe of the CIM. He died the same year.

International interest

In large, international cities such as Beijing,[63] foreign visitors have established Christian church communities which meet in public establishments such as hotels. These churches and fellowships, however, are typically restricted only to holders of non-Chinese passports.

American evangelist Billy Graham visited in China in 1988 with his wife, Ruth, and it was a homecoming for her since she had been born in China to missionary parents, L. Nelson Bell and his wife, Virginia.[64]

Since the 1980s, American officials visiting China have on multiple occasions visited Chinese churches, including President George W. Bush, who attended one of Beijing's five officially-recognized Protestant churches during a November 2005 Asia tour,[65] and the Kuanjie Protestant Church in 2008.[66][67] During an official visit to Beijing for the Beijing Olympic Games, Australian Prime Minister of Kevin Rudd with his wife Therese attended the Northern Cathedral, Beijing, for Sunday services in August 2008.[68] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice attended Palm Sunday services in Beijing in 2005.

During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, three American Christian protesters were deported from China after a demonstration at Tiananmen Square,[69][70][71] and eight Dutch Christians were stopped after attempting to sing in chorus.[72] Pope Benedict XVI urged China to be open to Christianity, and said that he hoped the Olympic Games would offer an example of coexistence among people from different countries.[73]

Christianity by Country

North AmericaSouth AmericaOceaniaSee also

- Christianity in India

- Chinese house church

- Chinese Union Version of the Bible

- Chinese New Hymnal

- China Christian Council

- Historical Bibliography of Christianity in China

- Historical Bibliography of the China Inland Mission

- Protestant missions in China 1807–1953

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in the People's Republic of China

- Timeline of Christian missions

References

- Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- Burgess, Alan (1957). The Small Woman. ISBN 1568491840.

- Gulick, Edward V. (1975). Peter Parker and the Opening of China. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 95, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1975).

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1929). A History of Christian Missions in China.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393307808.

- Taylor, James Hudson (1868). China's Spiritual Need and Claims (Third Edition). London: James Nisbet.

- Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 13.

Notes

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Missionary herald, Volume 17, by American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a publication from 1821 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Missionary herald, Volume 17, by American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a publication from 1821 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General, a publication from 1904 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General, a publication from 1904 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113, by Making of America Project, a publication from 1914 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113, by Making of America Project, a publication from 1914 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ a b Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.165

- ^ McGeown, Kate (2004-11-09). "China's Christians suffer for their faith". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/3993857.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Ding, Wang (2006). "Remnants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval ages". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter (editors). Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 9783805005340.

- ^ Hofrichter, Peter L. (2006). "Preface". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter (editors). Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 9783805005340.

- ^ Keung. Ching Feng. pp. 235.

- ^ Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1. s.n.. 1863. p. 18. http://books.google.com/books?id=04kdAAAAMAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=snippet&q=mohammedans%20and%20jews%20fraternal%20link&f=false. Retrieved 2011-7-06.

- ^ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 474. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6wEMAAAAYAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=onepage&q=nestorians%20mohammedanism%20rome&f=false. Retrieved 2011-5-08.

- ^ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 475. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6wEMAAAAYAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=snippet&q=roman%20catholics%20nestorians%20doctrine&f=false. Retrieved 2011-5-08.

- ^ Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims". The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 15. http://www.islamicpopulation.com/asia/China/China_integration%20of%20religious%20minority.pdf. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.164

- ^ Robert Samuel Maclay (1861). Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China. Carlton & Porter. p. 336. http://books.google.com/books?id=BZAPAAAAIAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=onepage&q=mohammedan%20slaves%20to%20beys&f=false. Retrieved 2011-7-06.

- ^ Robert Samuel Maclay (1861). Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China. Carlton & Porter. p. 337. http://books.google.com/books?id=BZAPAAAAIAAJ&q=mohammedan#v=onepage&q=foreigners%20strangled%20or%20expelled&f=false. Retrieved 2011-7-06.

- ^ American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1821). The Missionary herald, Volume 17. BOSTON: Published for the Board by Samuel T. Armstrong. p. 198. http://books.google.com/books?id=icQPAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA198&dq=should+they+propagate+in+the+country+the+religion+of+heaven's+Lord&hl=en&ei=PPQ1Tom-EY7rgQePxaCxDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CFAQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2011-7-31.(Original from the New York Public Library)

- ^ God's Chinese Son, Jonathan Spence, 1996

- ^ Gulick, Edward V. (1975). Peter Parker and the Opening of China. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 95, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1975)., pp. 561-562

- ^ Burgess, Alan (1957). The Small Woman. ISBN 1568491840., pp. 47

- ^ Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 13., p. 151-178

- ^ Spence (1991), p. 206

- ^ Taylor (1865),

- ^ a b Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393307808., p. 206

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393307808., p. 208

- ^ Paul A. Cohen (1997). History in three keys: the boxers as event, experience, and myth. Columbia University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0231106513. http://books.google.com/books?id=ky4_whmgIZcC&pg=PA19&dq=bandits+after+suffering+defeat+at+big+swords+claimed+membership+in+the+catholic+church&hl=en&ei=zEXkTJrQB8P6lweJyaibDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=bandits%20after%20suffering%20defeat%20at%20big%20swords%20claimed%20membership%20in%20the%20catholic%20church&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Paul A. Cohen (1997). History in three keys: the boxers as event, experience, and myth. Columbia University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0231106513. http://books.google.com/books?id=jVESdBSMasMC&pg=PA114&dq=big+swords+bandits+converted&hl=en&ei=_jrkTLGFJ4KclgeH6_W7Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CEEQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Lanxin Xiang (2003). The origins of the Boxer War: a multinational study. Psychology Press. p. 114. ISBN 0700715630. http://books.google.com/books?id=lAxresT12ogC&pg=PA112&dq=german+stenz++kaiser+china&hl=en&ei=tUvkTLPUI4GKlwez--GrDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=christian%20converts%20falsified%20lawsuits&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General (1904). East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ..., Issues 2-4]. Printed for H. M. Stationery Off., by Darling. p. 17. http://books.google.com/books?id=8pgsAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA2-PA17&dq=chinese+officials+and+troops+were+sent+to+atuntze+in+april&hl=en&ei=cI4LTqevHNK4tgeV0oxU&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDwQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2011-6-28.

- ^ Benjamin R. Beede (1994). The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898-1934: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 0824056248. http://books.google.com/books?id=48g116X9IIwC&pg=PA50&dq=prince+tuan+replaced+prince+qing&hl=en&ei=HH7fTIzXAcOclgeYzJ24Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the rising sun: a history of the Japanese military. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 83. ISBN 0393040852. http://books.google.com/books?id=wkHyjjbv-yEC&dq=allied+casualties+1%2C000+tientsin+close&q=europeans+share+their+supplies#v=snippet&q=europeans%20share%20their%20supplies&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ Max Boot (2003). The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power. Basic Books. p. 80. ISBN 046500721X. http://books.google.com/?id=0lIg-lGwqBoC&pg=PA79&dq=En+Hai+ketteler#v=onepage&q=starving%20chinese%20converts%20tree%20bark%20leaves%20suffer%20most&f=false. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Larry Clinton Thompson (2009). William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: heroism, hubris and the "ideal missionary". McFarland. p. 123. ISBN 0786440082. http://books.google.com/?id=5K9BN96p1hcC&pg=PA123&dq=boxer+rebellion+chinese+christian+rape#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the rising sun: a history of the Japanese military. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 70. ISBN 0393040852. http://books.google.com/books?id=wkHyjjbv-yEC&pg=PA70&dq=sugiyama+akira&hl=en&ei=h_3_TLrBCIP88Aar4rnzBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CDUQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=provocations%20by%20foreigners&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ Making of America Project (1914). The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113. Atlantic Monthly Co.. p. 80. http://books.google.com/?id=rcdkmohiuuQC&pg=PA80&dq=kansu+braves&cd=2#v=onepage&q=kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Blumhofer, Edith Waldvogel (1993). Modern Christian Revivals. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252019903. p.162

- ^ Kauffman, Paul E.: China Yesterday. Hong Kong: Asian Outreach, 1975: 100-101.

- ^ a b c d e Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.168

- ^ Counting Christians in China: a cautionary report. Industry & Business Article - Research, News, Information, Contacts, Divisions, Subsidiaries, Business Associations

- ^ Church growth in China.(Century marks)(Brief article) Industry & Business Article - Research, News, Information, Contacts, Divisions, Subsidiaries, Business Associations

- ^ a b Sons of heaven: Inside China’s fastest-growing non-governmental organisation The Economist October 2, 2008.

- ^ Latourette, (1929)

- ^ "Christianity finds a fulcrum in Asia". Asia Times Online. 2007-08-07. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/IH07Ad03.html. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2007". U.S. Embassy in Beijing. http://beijing.usembassy-china.org.cn/2007irf_china.html. Retrieved 2008-08-10.[dead link]

- ^ "China: Persecution of Protestant Christians in the Approach to the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games" (PDF). Christian Solidarity Worldwide. ChinaAid. http://chinaaid.org/pdf/Pre-Olympic_CHina_Persecution_Report_in_English_June2008.pdf. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ a b Werner Bürklin: Facts about Numbers of Christians in China The Gospel Herald, December 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c Mark Ellis: China Survey Reveals Fewer Christians than Some Evangelicals Want to Believe ASSIST News Service, October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c Mark Ellis: New China survey reveals fewer Christians than most estimates Christian Examiner, November 2007.

- ^ a b CIA - The World Factbook - China

- ^ Christianity_in_China#Demographics.2FGeography

- ^ See [1]

- ^ See[2]

- ^ See[3]

- ^ a b c d e See U.S. State Department "International Religious Freedom Report 2008"

- ^ "Church in Talks to "Regularize" Activities in China" (Press release). August 30, 2010. http://lds.org/ldsnewsroom/eng/news-releases-stories/church-in-talks-to-regularize-activities-in-china. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ a b God is Back Allen Lane 2009

- ^ China in Brief - china.org.cn

- ^ a b "Survey finds 300m China believers". BBC News. 2007-02-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/6337627.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ China Refutes Distortions about Christianity (date unclear)

- ^ Taipei Times

- ^ Simon Elegant: The War For China's SoulTime Magazine, August 20, 2006.

- ^ The CIA World Factbook - China

- ^ Jerry Dykstra: Key Chinese House Church Leader's Testimony CBN.com - date unclear

- ^ Horne (1904), chapter 5

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.167

- ^ BICF

- ^ "Billy Graham: an appreciation: wherever one travels around the world, the names of three Baptists are immediately known and appreciated--Jimmy Carter, Billy Graham and Martin Luther King, Jr. One is a politician, one an evangelist, and the other was a civil rights leader. All of them have given Baptists and the Christian faith a good reputation. (Biography)". Baptist History and Heritage. June 22, 2006. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-87912863.html. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ^ Washington Post

- ^ "President Bush Visited Officially Staged Church Service; House Church Pastor Hua Huiqi Arrested and Escaped from Police Custody". China Aid. 2008-08-10. http://chinaaid.org/2008/08/10/president-bush-visited-officially-staged-church-service-house-church-pastor-hua-huiqi-arrested-and-escaped-from-police-custody/. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ "Bush visits controversial Beijing church". Beijing News. 2008-08-10. http://www.beijingnews.net/story/392406. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ http://www.pm.gov.au/media/Interview/2008/interview_0405.cfm

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (2008-08-07). "Beijing police stop protest by U.S. Christians". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/reutersComService_2_MOLT/idUSPEK25586720080807. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Schou, Solvej (2008-08-08). "Protesters describe removal from Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5iLUVzKVLqTwTnsnkUtG9jBn360LAD92E0H6O1. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Carlson, Mark (2008-08-07). "U.S. Demonstrators Taken From Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. http://www.youtube.com/watch?=&v=IvMTdU7mt0c. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ "Three Protesters Dragged Away From Tiananmen Square". Epoch Times. 2008-08-07. http://en.epochtimes.com/n2/china/three-protesters-dragged-away-from-tiananmen-square-2381.html. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Petroff, Daniela (2008-08-07). "U.S. Demonstrators Taken From Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5j8scKG-FfneMOZ5isbjwtVvYg8gAD92CB0SGC. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

Further reading

- The Church of the Tang Dynasty, John Foster, SPCK, London, 1939

- The Lost Churches of China, Leonard M. Outerbridge, Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1952

- Tsui, Ambrose Pui Ho (1992). The principle of hou: A source for Chinese Christian ethics (M.A. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- The Story of Mary Liu, Edward Hunter, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1956

- Come Wind, Come Weather, Leslie Lyall, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1956

- Red Sky at Night, Leslie Lyall, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1961

- Christianity in China, George N. Patterson, World Books, London, 1969

- The Cross and the Lotus, Lee Shiu Keung, Christian Study Centre on Chinese Religion and Culture, Hong Kong, 1971

- Decision for China, Paul T. K. Shi, St John's University Press, N.Y., 1971

- The Jesus Family in China, D. Vaughan Rees, Paternoster Press, Exeter, 1973

- Christians and China, V. Hayward, Christian Journals Ltd, Belfast, 1974

- Nathan Sites: An Epic of the East, Sarah Moore Sites, Revell, New York, 1912

- The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, Jonathan D. Spence, New York, 1984

- Jesus in Beijing, David Aikman, Regnery Publishing Inc., Washington D.C., 2003

- China's Christian Millions (New Edition, Fully Revised and Updated) Lambert, Tony (2006)