- Christianity in the United States

-

Christianity by Country

North AmericaSouth AmericaOceaniaPictured is a Coptic Orthodox Church in Bellaire, Texas.

Christianity is the largest and most popular religion in the United States, with around 77% of those polled identifying themselves as Christian, as of 2009.[1][2][3] This is down from 86% in 1990, and slightly lower than 78.6% in 2001.[4] About 62% of those polled claim to be members of a church congregation.[5] In the mid 1990's the United States had the largest Christian population on earth, with 224 million Christians.[6]

Protestant denominations accounted for 51.3%, while Roman Catholicism, at 23.9%, was the largest individual denomination. The study categorizes white evangelicals, 26.3% of the population, as the country's largest religious cohort;[3] another study estimates evangelicals of all races at 30–35%.[7]

Christianity was introduced to the Americas as it was first colonized by Europeans beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries. Today most Christian churches are Mainline Protestant, Evangelical, or Roman Catholic.

Contents

Major denominational families

United States Christian bodies United States InterchurchCatholic & AnglicanHoliness & PietistLutheranMethodistPentecostalPresbyterian & ReformedOtherChristian denominations in the United States are usually divided in three large groups, Evangelicalism, Mainline Protestantism and Roman Catholicism. Christian denominations that do not fall within either of these groups are mostly associated with ethnic minorities, i.e. the various denominations of Eastern Orthodoxy.

A 2004 survey of the United States identified the percentages of these groups as 26.3% (Evangelical), 22% (Roman Catholics), and 16% (Mainline Protestant.)[7] In a Statistical Abstract of the United States, based on a 2001 study of the self-described religious identification of the adult population, the percentages for these same groups are 28.6% (Evangelical), 24.5% (Roman Catholics), and 13.9% (Mainline Protestant.) [8]

Roman Catholic Church

Main article: Catholic Church in the United States The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. is the largest Catholic church in the United States.

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. is the largest Catholic church in the United States.

Roman Catholicism arrived in what is now the United States during the earliest days of the European colonization of the Americas. At the time the country was founded (meaning the Thirteen Colonies in 1776), only a small fraction of the population there were Catholics (mostly Maryland); however, as a result of expansion and immigration over the country's history, the number of adherents has grown dramatically and it is now the largest profession of faith in the United States today. With over 67 million registered residents professing the faith in 2008, the United States has the fourth largest Catholic population in the world after Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines, respectively.

The Church's leadership body in the United States is the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, made up of the hierarchy of bishops and archbishops of the United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands, although each bishop is independent in his own diocese, answerable only to the Pope.

No primate for Catholics exists in the United States. The Archdiocese of Baltimore has Prerogative of Place, which confers to its archbishop a subset of the leadership responsibilities granted to primates in other countries.

Protestantism

Main article: Protestantism in the United StatesIn typical usage, the term mainline is contrasted with evangelical.

The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) counts 26,344,933 members of mainline churches versus 39,930,869 members of evangelical Protestant churches.[9] There is evidence that there has been a shift in membership from mainline denominations to evangelical churches.[10]

As shown in the table below, some denominations with similar names and historical ties to Evangelical groups are considered Mainline.

Protestant: Mainline vs. Evangelical Family: Total:[8] US%[8] Examples: Type: Baptist 38,662,005 25.3% Southern Baptist Convention Evangelical American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A. Mainline Pentecostal 13,673,149 8.9% Assemblies of God Evangelical Lutheran 7,860,683 5.1% Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Mainline Lutheran Church, Missouri Synod Evangelical Presbyterian/

Reformed5,844,855 3.8% Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Mainline Presbyterian Church in America Evangelical Methodist 5,473,129 3.6% United Methodist Church Mainline African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church Evangelical Anglican 2,323,100 1.5% Episcopal Church Mainline Adventist 2,203,600 1.4% Seventh-Day Adventist Church Evangelical Holiness 2,135,602 1.4% Church of the Nazarene Evangelical Other Groups 1,366,678 0.9% Church of the Brethren Evangelical Friends General Conference Mainline Evangelicalism

Main article: EvangelicalismEvangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement. In typical usage, the term mainline is contrasted with evangelical. Theologically conservative critics accuse the mainline churches of "the substitution of leftist social action for Christian evangelizing, and the disappearance of biblical theology," and maintain that "All the Mainline churches have become essentially the same church: their histories, their theologies, and even much of their practice lost to a uniform vision of social progress."[11] Most adherents consider its key characteristics to be: a belief in the need for personal conversion (or being "born again"); some expression of the gospel in effort; a high regard for Biblical authority; and an emphasis on the death and resurrection of Jesus.[12] David Bebbington has termed these four distinctive aspects conversionism, activism, biblicism, and crucicentrism, saying, "Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."[13]

Note that the term "Evangelical" does not equal Fundamentalist Christianity, although the latter is sometimes regarded simply as the most theologically conservative subset of the former. The major differences largely hinge upon views of how to regard and approach scripture ("Theology of Scripture"), as well as construing its broader world-view implications. While most conservative Evangelicals believe the label has broadened too much beyond its more limiting traditional distinctives, this trend is nonetheless strong enough to create significant ambiguity in the term.[14] As a result, the dichotomy between "evangelical" vs. "mainline" denominations is increasingly complex (particularly with such innovations as the "Emergent Church" movement).

The contemporary North American usage of the term is influenced by the evangelical/fundamentalist controversy of the early 20th century. Evangelicalism may sometimes be perceived as the middle ground between the theological liberalism of the Mainline (Protestant) denominations and the cultural separatism of Fundamentalist Christianity.[15] Evangelicalism has therefore been described as "the third of the leading strands in American Protestantism, straddl[ing] the divide between fundamentalists and liberals."[16] While the North American perception is important to understand the usage of the term, it by no means dominates a wider global view, where the fundamentalist debate was not so influential.

Evangelicals held the view that the modernist and liberal parties in the Protestant churches had surrendered their heritage as Evangelicals by accommodating the views and values of the world. At the same time, they criticized their fellow Fundamentalists for their separatism and their rejection of the Social Gospel as it had been developed by Protestant activists of the previous century. They charged the modernists with having lost their identity as Evangelicals and the Fundamentalists with having lost the Christ-like heart of Evangelicalism. They argued that the Gospel needed to be reasserted to distinguish it from the innovations of the liberals and the fundamentalists.

They sought allies in denominational churches and liturgical traditions, disregarding views of eschatology and other "non-essentials," and joined also with Trinitarian varieties of Pentecostalism. They believed that in doing so, they were simply re-acquainting Protestantism with its own recent tradition. The movement's aim at the outset was to reclaim the Evangelical heritage in their respective churches, not to begin something new; and for this reason, following their separation from Fundamentalists, the same movement has been better known merely as "Evangelicalism." By the end of the 20th century, this was the most influential development in American Protestant Christianity.[citation needed]

The National Association of Evangelicals is a U.S. agency which coordinates cooperative ministry for its member denominations.

Mainline Protestantism

Main article: Mainline (Protestant)The mainline Protestant Christian denominations are those Protestant denominations that were brought to the United States by its historic immigrant groups; for this reason they are sometimes referred to as heritage churches.[17] The largest are the Episcopal (English), Presbyterian (Scottish), Methodist (English and Welsh), and Lutheran (German and Scandinavian) churches.

Many mainline denominations teach that the Bible is God's word in function, but tend to be open to new ideas and societal changes.[18] They have been increasingly open to the ordination of women. Mainline churches tend to belong to organizations such as the National Council of Churches and World Council of Churches.

The seven largest U.S. mainline denominations were called by William Hutchison the "Seven Sisters of American Protestantism."[19][20] in reference to the major liberal groups during the period between 1900 to 1960.

- United Methodist Church 7,931,733 members (2008)[21]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 4,709,956 members (2008)[21]

- Presbyterian Church (USA) 2,209,546 members (2007)[22]

- Episcopal Church in the United States of America (2008) 2,116,749 members[21]

- American Baptist Churches in the USA 1,358,351 members (2008)[21]

- United Church of Christ 1,145,281 members (2008)[21]

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) 691,160 (2008)

The Association of Religion Data Archives also considers these denominations to be mainline:[9]

- Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) 350,000 members

- Reformed Church in America 269,815 members (2005)[23]

- International Council of Community Churches 108,806 members (2005)[24]

- National Association of Congregational Christian Churches 65,569 members (2000)[25]

- North American Baptist Conference 64,565 members (2002)

- Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches 44,000 members (1998)[26]

- Moravian Church in America, Northern Province 24,650 members (2003)[27]

- Moravian Church in America, Southern Province 21,513 members (1991)[28]

- Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 12,000 members (2007)

- Congregational Christian Churches, (not part of any national CCC body)

- Moravian Church in America, Alaska Province

The Association of Religion Data Archives has difficulties collecting data on traditionally African American denominations. Those churches most likely to be identified as mainline include these Methodist groups:

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Salt Lake Temple, which took 40 years to build, is one of the most iconic images of the church

The Salt Lake Temple, which took 40 years to build, is one of the most iconic images of the church

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or LDS Church) is a nontrinitarian restorationist denomination. The church is headquartered in Salt Lake City, and is the largest originating from the Latter Day Saint movement which was founded by Joseph Smith, Jr. in Upstate New York in 1830. The church currently claims a growing membership of over 14.1 million,[29] and the current and 16th President is Thomas S. Monson.

Eastern Christianity

Further information: Eastern Orthodoxy in the WestThe Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) as of 2000 reported just below 1 million of adherents of Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox denominations in the US, or 0.4% of total population.[30]

History

Main article: History of Christianity in the United StatesChristianity was introduced during the period of European colonization. The Spanish and French brought Roman Catholicism to the colonies of New Spain and New France respectively, while Northern European peoples introduced Protestantism. Among Protestants, adherents to Anglicanism, the Baptist Church, Congregationalism, Presbyterianism, Lutheranism, Quakerism, Mennonite and Moravian Church were the first to settle to the US spreading their faith in the new country.

Early Colonial period

French Huguenots settled Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida on June 22, 1564, as a refuge from the religious persecution they faced in Europe. This colony was destroyed the next year by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the settlers of the Spanish colony of St. Augustine to the south.[31]

The Dutch founded their colony of New Netherland in 1624;[32] they established the Dutch Reformed Church as the colony's official religion in 1628.[33]

Spanish colonies

The earliest Christians in the United States were Spanish Roman Catholic settlers and missionaries (primarily Franciscan missionaries) in Puerto Rico. Christopher Columbus and his men were the first Europeans to come to Puerto Rico when they landed there in 1493 during Columbus' second voyage; Juan Ponce de León founded the first European settlement on the island in Caparra in 1508.

The first Christian worship service held in what is now the continental United States was a Roman Catholic mass celebrated 1559 in the colony founded by Tristán de Luna y Arellano at what is now Pensacola, Florida. Roman Catholic services were also held in longer-lasting colony of St. Augustine, also in Florida, from its founding in 1565. Later, the Spanish spread Roman Catholicism through Spanish Florida by way of its mission system; these missions extended into Georgia and the Carolinas. Eventually, Spain established missions in what are now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

In the English colonies, Roman Catholicism was introduced with the settling of Maryland.

Conversion of Native Americans into Roman Catholicism was sometimes met with hostilities by tribesmen of the converts. For example, in 1700 Hopi Indians destroyed Awatovi pueblo inhabited by converts, killed all the men and scattered the women and children among the other villages.[34]

British colonies

Many of the British North American colonies that eventually formed the United States of America were settled in the 17th century by men and women, who, in the face of European religious persecution, refused to compromise passionately-held religious convictions and fled Europe.

New England

A group which later became known as the Pilgrims settled the Plymouth Colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, seeking refuge from persecution in Europe.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. Puritans were English Protestants who wished to reform and purify the Church of England in the New World of what they considered to be unacceptable residues of Roman Catholicism. Within two years, an additional 2,000 settlers arrived. Beginning in 1630, as many as 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America from England to gain the liberty to worship as they chose. Most settled in New England, but some went as far as the West Indies. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalists." The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation." The presence of the Puritans in New England and tension over land disputes with the Native Americans eventually led to King Philip's War in 1675 to save, from the Natives' point of view, the tribes from extinction. The fire power of the Puritans and other colonists virtually exterminated the bulk of the Wampanoags and Narragansetts. King Philip (Metacom) was killed and the captured Native women and children of the tribes (including Philip's wife and son) were sold into slavery in the West Indies.[35][36]

Virginia

Virginia was settled by businessmen operating through a joint-stock company, the Virginia Company of London, who wanted to get rich. They also wanted the Church to flourish in their colony and kept it well supplied with ministers. Some early governors sent by the Virginia Company acted in the spirit of crusaders. During governor Thomas Dale's tenure, religion was spread at the point of the sword. Everyone was required to attend church and be catechized by a minister. Those who refused could be executed or sent to the galleys.

When a popular assembly, the House of Burgesses, was established in 1619, it enacted religious laws that "were a match for anything to be found in the Puritan societies." Unlike the colonies to the north, where the Church of England was regarded with suspicion throughout the colonial period, Virginia was a bastion of Anglicanism.

The church in Virginia faced problems unlike those confronted in other colonies—such as enormous parishes, some sixty miles long, and the inability to ordain ministers locally—but it continued to command the loyalty and affection of the colonists.

Tolerance in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania

Roger Williams, who preached religious tolerance, separation of church and state, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished from Massachusetts and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other religious refugees from the Puritan community. Some migrants who came to Colonial America were in search of the freedom to practice forms of Christianity which were prohibited and persecuted in Europe. Since there was no state religion, and since Protestantism had no central authority, religious practice in the colonies became diverse.

The Religious Society of Friends formed in England in 1652 around leader George Fox. Quakers were severely persecuted in England for daring to deviate so far from orthodox Christianity. This reign of terror impelled Friends to seek refuge in New Jersey in the 1670s, where they soon became well entrenched. In 1681, when Quaker leader William Penn parlayed a debt owed by Charles II to his father into a charter for the province of Pennsylvania, many more Quakers were prepared to grasp the opportunity to live in a land where they might worship freely. By 1685, as many as 8,000 Quakers had come to Pennsylvania. Although the Quakers may have resembled the Puritans in some religious beliefs and practices, they differed with them over the necessity of compelling religious uniformity in society.

Beginning in 1683 many immigrants arrived in Pennsylvania from the German Rhine Valley and Switzerland. Starting in the 1730s Count Zinzendorf and the Moravian Brethren sought to minister to these immigrants while they also began missions among the Native American tribes of New York and Pennsylvania. Heinrich Melchior Muehlenberg organized the first Lutheran Synod in Pennsylvania in the 1740s.

The efforts of the founding fathers to find a proper role for their support of religion—and the degree to which religion can be supported by public officials without being inconsistent with the revolutionary imperative of freedom of religion for all citizens—is a question that is still debated in the country today.

Maryland

Roman Catholic fortunes fluctuated in Maryland during the rest of the 17th century, as they became an increasingly smaller minority of the population. After the Glorious Revolution of 1689 in England, penal laws deprived Roman Catholics of the right to vote, hold office, educate their children or worship publicly. Until the American Revolution, Roman Catholics in Maryland, like Charles Carroll of Carrollton, were dissenters in their own country, but keeping loyal to their convictions. At the time of the Revolution, Roman Catholics formed less than 1% of the population of the thirteen colonies, in 2007, Roman Catholics comprised 24% of US population.

18th century

Scholars now identify a high level of religious energy in colonies after 1700. According to one expert, religion was in the "ascension rather than the declension"; another sees a "rising vitality in religious life" from 1700 onward; a third finds religion in many parts of the colonies in a state of "feverish growth." Figures on church attendance and church formation support these opinions. Between 1700 and 1740, an estimated 75-80% of the population attended churches, which were being built at a headlong pace.[citation needed]

By 1780 the percentage of adult colonists who adhered to a church was between 10-30%, not counting slaves or Native Americans. North Carolina had the lowest percentage at about 4%, while New Hampshire and South Carolina were tied for the highest, at about 16%.[37]

Great Awakening

Evangelicalism is difficult to date and to define. Scholars have argued that, as a self-conscious movement, evangelicalism did not arise until the mid-17th century, perhaps not until the Great Awakening itself. The fundamental premise of evangelicalism is the conversion of individuals from a state of sin to a "new birth" through preaching of the Word. The Great Awakening refers to a northeastern Protestant revival movement that took place in the 1730s and 1740s.

The first generation of New England Puritans required that church members undergo a conversion experience that they could describe publicly. Their successors were not as successful in reaping harvests of redeemed souls. The movement began with Jonathan Edwards, a Massachusetts preacher who sought to return to the Pilgrims' strict Calvinist roots. British preacher George Whitefield and other itinerant preachers continued the movement, traveling across the colonies and preaching in a dramatic and emotional style. Followers of Edwards and other preachers of similar religiosity called themselves the "New Lights," as contrasted with the "Old Lights," who disapproved of their movement. To promote their viewpoints, the two sides established academies and colleges, including Princeton and Williams College. The Great Awakening has been called the first truly American event.

The supporters of the Awakening and its evangelical thrust—Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists—became the largest American Protestant denominations by the first decades of the 19th century. By the 1770s, the Baptists were growing rapidly both in the north (where they founded Brown University), and in the South. Opponents of the Awakening or those split by it—Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists—were left behind.

American Revolution

The Revolution split some denominations, notably the Church of England, whose ministers were bound by oath to support the king, and the Quakers, who were traditionally pacifists. Religious practice suffered in certain places because of the absence of ministers and the destruction of churches, but in other areas, religion flourished.

The American Revolution inflicted deeper wounds on the Church of England in America than on any other denomination because the King of England was the head of the church. The Book of Common Prayer offered prayers for the monarch, beseeching God "to be his defender and keeper, giving him victory over all his enemies," who in 1776 were American soldiers as well as friends and neighbors of American Anglicans. Loyalty to the church and to its head could be construed as treason to the American cause. Patriotic American Anglicans, loathing to discard so fundamental a component of their faith as The Book of Common Prayer, revised it to conform to the political realities.

Another result of this was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from England by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church.

During this time, the Russians had been missionizing the native peoples in Alaska. In 1794, the Orthodox Saint, St. Herman of Alaska and missionaries arrived on Kodiak island and began significantly evangelizing the native peoples. The period between this and the purchase of Alaska by the United States included successful missionizing of Alaskan natives to the Orthodox faith, including ordaining them & changing services to the native languages. Orthodoxy also was present in the mainland United States prior to the purchase of Alaska. However, here it was present in the form of immigrants coming to America from Europe, Africa, the Middle East. Here it was mostly kept within cultural boundaries with some conversions/evangelizing, though most growth came through immigration.

Church and State Debate

After independence the American states were obliged to write constitutions establishing how each would be governed. For three years, from 1778 to 1780, the political energies of Massachusetts were absorbed in drafting a charter of government that the voters would accept. One of the most contentious issues was whether the state would support the church financially. Advocating such a policy were the ministers and most members of the Congregational Church, which received public financial support, during the colonial period. The Baptists tenaciously adhered to their ancient conviction that churches should receive no support from the state. The Constitutional Convention chose to support the church and Article Three authorized a general religious tax to be directed to the church of a taxpayers' choice.

Such tax laws also took effect in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

The 19th century

Separation

In October 1801, members of the Danbury Baptists Associations wrote a letter to the new president-elect Thomas Jefferson. Baptists, being a minority in Connecticut, were still required to pay fees to support the Congregationalist majority. The Baptists found this intolerable. The Baptists, well aware of Jefferson's own unorthodox beliefs, sought him as an ally in making all religious expression a fundamental human right and not a matter of government largesse.

In his January 1, 1802 reply to the Danbury Baptist Association Jefferson summed up the First Amendment's original intent, and used for the first time anywhere a now-familiar phrase in today's political and judicial circles: the amendment established a "wall of separation between church and state." Largely unknown in its day, this phrase has since become a major Constitutional issue. The first time the U.S. Supreme Court cited that phrase from Jefferson was in 1878, 76 years later.

Revivalism

During the Second Great Awakening Christianity grew and took root in new areas, along with new Protestant denominations such as Adventism, the Restoration Movement, and groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormonism. While the First Great Awakening was centered on reviving the spirituality of established congregations, the Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s), unlike the first, focused on the unchurched and sought to instill in them a deep sense of personal salvation as experienced in revival meetings.

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, Bishop Francis Asbury led the American Methodist movement as one of the most prominent religious leaders of the young republic. Traveling throughout the eastern seaboard, Methodism grew quickly under Asbury's leadership into one of the nation's largest and most influential denominations.

The principal innovation produced by the revivals was the camp meeting. The revivals were organized by Presbyterian ministers who modeled them after the extended outdoor "communion seasons," used by the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, which frequently produced emotional, demonstrative displays of religious conviction. In Kentucky, the pioneers loaded their families and provisions into their wagons and drove to the Presbyterian meetings, where they pitched tents and settled in for several days.

When assembled in a field or at the edge of a forest for a prolonged religious meeting, the participants transformed the site into a camp meeting. The religious revivals that swept the Kentucky camp meetings were so intense and created such gusts of emotion that their original sponsors, the Presbyterians, soon repudiated them. The Methodists, however, adopted and eventually domesticated camp meetings and introduced them into the eastern United States, where for decades they were one of the evangelical signatures of the denomination.

African American Churches

The Christianity of the black population was grounded in evangelicalism. The Second Great Awakening has been called the "central and defining event in the development of Afro-Christianity." During these revivals Baptists and Methodists converted large numbers of blacks. However, many were disappointed at the treatment they received from their fellow believers and at the backsliding in the commitment to abolish slavery that many white Baptists and Methodists had advocated immediately after the American Revolution.

When their discontent could not be contained, forceful black leaders followed what was becoming an American habit—they formed new denominations. In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the Methodist Church and in 1815 founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

After the Civil War, Black Baptists desiring to practice Christianity away from racial discrimination, rapidly set up several separate state Baptist conventions. In 1866, black Baptists of the South and West combined to form the Consolidated American Baptist Convention. This Convention eventually collapsed but three national conventions formed in response. In 1895 the three conventions merged to create the National Baptist Convention. It is now the largest African-American religious organization in the United States.

Liberal Christianity

The "secularization of society" is attributed to the time of the Enlightenment. In the United States, religious observance is much higher than in Europe, and the United States' culture leans conservative in comparison to other western nations, in part due to the Christian element.

Liberal Christianity, exemplified by some theologians, sought to bring to churches new critical approaches to the Bible. Sometimes called liberal theology, liberal Christianity is an umbrella term covering movements and ideas within 19th and 20th century Christianity. New attitudes became evident, and the practice of questioning the nearly universally accepted Christian orthodoxy began to come to the forefront.

In the post–World War I era, liberalism was the faster growing sector of the American church. Liberal wings of denominations were on the rise, and a considerable number of seminaries held and taught from a liberal perspective as well. In the post–World war II era, the trend began to swing back towards the conservative camp in America's seminaries and church structures.

Roman Catholicism

Main article: History of Roman Catholicism in the United StatesSee also: Catholic Church in the United StatesBy 1850 Roman Catholics had become the country's largest single denomination. Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled through immigration; by the end of the decade it would reach seven million. These huge numbers of immigrant Catholics came from Ireland, Southern Germany, Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe. This influx would eventually bring increased political power for the Roman Catholic Church and a greater cultural presence, led at the same time to a growing fear of the Catholic "menace." As the 19th century wore on animosity waned, Protestant Americans realized that Roman Catholics were not trying to seize control of the government.

Fundamentalism

Bethesda Temple Apostolic Church in Dayton, Ohio

Bethesda Temple Apostolic Church in Dayton, Ohio

Christian fundamentalism began as a movement in the late 19th century and early 20th century to reject influences of secular humanism and source criticism in modern Christianity. In reaction to liberal Protestant groups that denied doctrines considered fundamental to these conservative groups, they sought to establish tenets necessary to maintaining a Christian identity, the "fundamentals," hence the term fundamentalist.

Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by secular scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists grew in various denominations as independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity.

Over time, the movement divided, with the label Fundamentalist being retained by the smaller and more hard-line group(s). Evangelical has become the main identifier of the groups holding to the movement's moderate and earliest ideas.

The 20th century

Evangelicalism

In the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, there has been a marked rise in the evangelical wing of Protestant denominations, especially those that are more exclusively evangelical, and a corresponding decline in the mainstream liberal churches.

The 1950s saw a boom in the Evangelical church in America. The post–World War II prosperity experienced in the U.S. also had its effects on the church. Church buildings were erected in large numbers, and the Evangelical church's activities grew along with this expansive physical growth. In the southern U.S., the Evangelicals, represented by leaders such as Billy Graham, have experienced a notable surge displacing the caricature of the pulpit pounding country preachers of fundamentalism. The stereotypes have gradually shifted.

Although the Evangelical community worldwide is diverse, the ties that bind all Evangelicals are still apparent: a "high view" of Scripture, belief in the Deity of Christ, the Trinity, salvation by grace through faith, and the bodily resurrection of Christ.

National Associations

The Federal Council of Churches, founded in 1908, marked the first major expression of a growing modern ecumenical movement among Christians in the United States. It was active in pressing for reform of public and private policies, particularly as they impacted the lives of those living in poverty, and developed a comprehensive and widely debated Social Creed which served as a humanitarian "bill of rights" for those seeking improvements in American life.

In 1950, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA (usually identified as National Council of Churches, or NCC) represented a dramatic expansion in the development of ecumenical cooperation. It was a merger of the Federal Council of Churches, the International Council of Religious Education, and several other interchurch ministries. Today, the NCC is a joint venture of 35 Christian denominations in the United States with 100,000 local congregations and 45,000,000 adherents. Its member communions include Mainline Protestant, Orthodox, African-American, Evangelical and historic Peace churches. The NCC took a prominent role in the Civil Rights movement, and fostered the publication of the widely-used Revised Standard Version of the Bible, followed by an updated New Revised Standard Version, the first translation to benefit from the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The organization is headquartered in New York City, with a public policy office in Washington, DC. The NCC is related fraternally to hundreds of local and regional councils of churches, to other national councils across the globe, and to the World Council of Churches. All of these bodies are independently governed.

Carl McIntire led in organizing the American Council of Christian Churches (ACCC), now with 7 member bodies, in September 1941. It was a more militant and fundamentalist organization set up in opposition to what became the National Council of Churches.

The National Association of Evangelicals for United Action was formed in St. Louis, Missouri on April 7–9, 1942. It soon shortened its name to the National Association of Evangelicals (NEA). There are currently 60 denominations with about 45,000 churches in the organization. The NEA is related fraternally the World Evangelical Fellowship.

Pentecostalism

Another noteworthy development in 20th-century Christianity was the rise of the modern Pentecostal movement. Pentecostalism, which had its roots in the Pietism and the Holiness movement, arose out of the meetings in 1906 at an urban mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles. From there it spread by those who experienced what they believed to be miraculous moves of God there.

Pentecostalism would later birth the Charismatic movement within already established denominations, and it continues to be an important force in western Christianity.

Roman Catholicism

By the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Roman Catholic. Modern Roman Catholic immigrants come to the United States from the Philippines, Poland, and Latin America, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism and diversity has greatly impacted the flavor of Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses serve in both the English language and the Spanish language.

Demographics

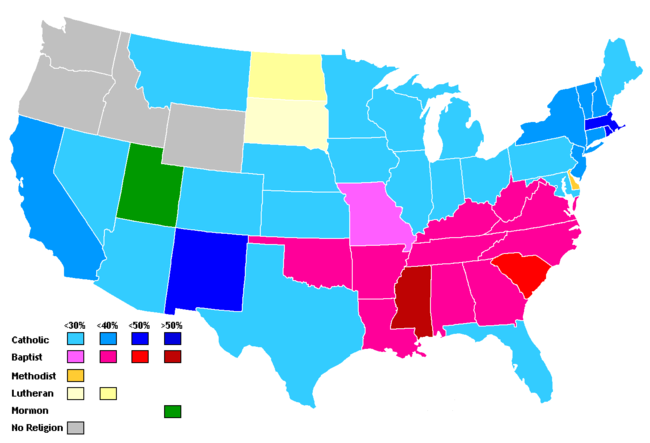

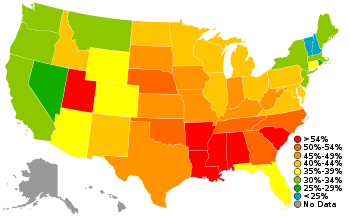

Demographics by state

Numbers in the chart below come from statistics collected by the ASARB[38] in surveys of the churches themselves. Congregational "adherents" include all full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services.Beliefs and attitudes

The Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion conducted a survey covering various aspects of American religious life.[39] The researchers analyzing the survey results have categorized the responses into what they call the "four Gods": An authoritarian God (31%), a benevolent God (25%), a distant God (23%), and a critical God (16%).[39] A major implication to emerge from this survey is that "the type of god people believe in can predict their political and moral attitudes more so than just looking at their religious tradition."[39]

As far as religious tradition, the survey determined that 33.6% of respondents are evangelical Protestants, while 10.8% had no religious affiliation at all. Out of those without affiliation, 62.9% still indicated that they "believe in God or some higher power".[39]

Another study, conducted by Christianity Today with Leadership magazine, attempted to understand the range and differences among American Christians. A national attitudinal and behavioral survey found that their beliefs and practices clustered into five distinct segments. Spiritual growth for two large segments of Christians may be occurring in non-traditional ways. Instead of attending church on Sunday mornings, many opt for personal, individual ways to stretch themselves spiritually.[40]

- 19 percent of American Christians are described by the researchers as Active Christians. They believe salvation comes through Jesus Christ, attend church regularly, are Bible readers, invest in personal faith development through their church, accept leadership positions in their church, and believe they are obligated to "share [their] faith", that is, to evangelize others.

- 20 percent are referred to as Professing Christians. They also are committed to "accepting Christ as Savior and Lord" as the key to being a Christian, but focus more on personal relationships with God and Jesus than on church, Bible reading or evangelizing.

- 16 percent fall into a category named Liturgical Christians. They are predominantly Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, or Orthodox. They are regular churchgoers, have a high level of spiritual activity and recognize the authority of the church.

- 24 percent are considered Private Christians. They own a Bible but don't tend to read it. Only about one-third attend church at all. They believe in God and in doing good things, but not necessarily within a church context. This was the largest and youngest segment. Almost none are church leaders.

- 21 percent in the research are called Cultural Christians. These do not view Jesus as essential to salvation. They exhibit little outward religious behavior or attitudes. They favor a universality theology that sees many ways to God. Yet, they clearly consider themselves to be Christians.

Church attendance

Gallup International indicates that 41%[41] of American citizens report they regularly attend religious services, compared to 15% of French citizens, 10% of UK citizens,[42] and 7.5% of Australian citizens.[43]

However, these numbers are open to dispute. ReligiousTolerance.org states:

- "Church attendance data in the U.S. has been checked against actual values using two different techniques. The true figures show that only about 21% of Americans and 10% of Canadians actually go to church one or more times a week. Many Americans and Canadians tell pollsters that they have gone to church even though they have not. Whether this happens in other countries, with different cultures, is difficult to predict."[41]

In, a 2006 online Harris Poll of 2,010 U.S. adults (18 and older) found that only 26% of those surveyed attended religious services "every week or more often", 9% went "once or twice a month", 21% went "a few times a year", 3% went "once a year", 22% went "less than once a year", and 18% never attend religious services. An identical survey by Harris in 2003 found that only 26% of those surveyed attended religious services "every week or more often", 11% went "once or twice a month" 19% went "a few times a year", 4% went "once a year", 16% went "less than once a year", and 25% never attend religious services.

By state

Church attendance varies a lot by state and region. In a 2006 Gallup survey, 42% of Americans said that they attended church or synagogue once a week or almost every week. The figures ranged from 58% in Alabama, Louisiana and South Carolina to 24% in Vermont and New Hampshire.

Church Attendance by State[44] Rank State Percent — National average 42% 1 Alabama 58% 1 Louisiana 58% 1 South Carolina 58% 4 Mississippi 57% 5 Arkansas 55% 5 Utah 55% 7 Nebraska 53% 7 North Carolina 53% 9 Georgia 52% 9 Tennessee 52% 11 Oklahoma 50% 12 Texas 49% 13 Kentucky 48% 14 Kansas 47% 15 Indiana 46% 15 Iowa 46% 15 Missouri 46% 15 West Virginia 46% 19 South Dakota 45% 20 Minnesota 44% 20 Virginia 44% 22 Delaware 43% 22 Idaho 43% 22 North Dakota 43% 22 Ohio 43% 22 Pennsylvania 43% 22 Wisconsin 43% 28 Illinois 42% 28 Michigan 42% 30 Maryland 41% 30 New Mexico 41% 32 Florida 39% 33 Connecticut 37% 34 Wyoming 36% 35 Arizona 35% 35 Colorado 35% 37 Montana 34% 37 New Jersey 34% 39 District of Columbia 33% 39 New York 33% 41 California 32% 41 Oregon 32% 41 Washington 32% 44 Maine 31% 44 Massachusetts 31% 46 Rhode Island 28% 47 Nevada 27% 48 New Hampshire 24% 48 Vermont 24% See also

- Demographics of the United States

- History of religion in the United States

- Religion in the United States

- Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches

References

- ^ Gallup, "This Christmas, 78% of Americans Identify as Christian", December 24, 2009. Accessed February 8, 2011.

- ^ American Religious Identification Survey 2008

- ^ a b Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: Religious Affiliation: Diverse and Dynamic. February 2008, pp. 5, 12. Accessed February 8, 2011.

- ^ "American Religious Identification Survey". CUNY Graduate Center. 2001. http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/key_findings.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ Finke, Roger; Rodney Stark (2005). The Churching of America, 1776-2005. Rutgers University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0813535530. online at Google Books.

- ^ Ash, Russell (1997). The Top 10 of Everything. DK Publishing, Inc.. p. 160-161.

- ^ a b Green, John C. "The American Religious Landscape and Political Attitudes: A Baseline for 2004". University of Akron. http://www.uakron.edu/bliss/docs/Religious_Landscape_2004.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ a b c The figures for this 2007 abstract are based on surveies for 1990 and 2001 from the Graduate School and University Center at the City University of New York. Kosmin, Barry A.; Egon Mayer, Ariela Keysar (2001). "American Religious Identification Survey". City University of New York.; Graduate School and University Center. http://www.trincoll.edu/NR/rdonlyres/AFCEF53A-8DAB-4CD9-A892-5453E336D35D/0/NEWARISrevised121901b.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ a b Mainline protestant denominations

- ^ "The U.S. Church Finance Market: 2005-2010" Non-denominational membership doubled between 1990 and 2001. (April 1, 2006, report)

- ^ The Death of Protestant America: A Political Theory of the Protestant Mainline by Joseph Bottum, First Things (August/September 2008)[1]

- ^ Eskridge, Larry (1995). "Defining Evangelicalism". Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals. http://www.wheaton.edu/isae/defining_evangelicalism.html. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Bebbington, p. 3.

- ^ George Marsden Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism Eerdmans, 1991.

- ^ Luo, Michael (2006-04-16). "Evangelicals Debate the Meaning of 'Evangelical'". The New York Times (nytimes.com). http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/16/weekinreview/16luo.html?_r=1&adxnnlx=1145227368-p%20hJwvCXS0qceSTw%20jLi8w&pagewanted=all.

- ^ Mead, Walter Russell (2006). "God's Country?". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20060901faessay85504-p20/walter-russell-mead/god-s-country.html. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ The Death of Protestant America: A Political Theory of the Protestant Mainline by Joseph Bottum, First Things (August/September 2008)[2]

- ^ The Decline of Mainline Protestantism

- ^ Protestant Establishment I (Craigville Conference)

- ^ Hutchison, William. Between the Times: The Travail of the Protestant Establishment in America, 1900-1960 (1989), Cambridge U. Press, ISBN 0-521-40601-3

- ^ a b c d e NCC - 2009 Yearbook of American & Canadian Churches

- ^ PC(USA) Congregations and Membership — 1997-2007

- ^ Reformed membership

- ^ ICCC membership

- ^ NACCC membership

- ^ UFMCC membership

- ^ Moravian Northern Province membership

- ^ Moravian Southern Province membership

- ^ "2010 Statistical Report for 2011 April General Conference". http://newsroom.lds.org/article/2010-statistical-report-for-2011-april-general-conference.

- ^ "ARDA Sources for Religious Congregations & Membership Data". ARDA. 2000. http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/rcms_notes.asp. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/timu/historyculture/foca_chronology.htm

- ^ http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/us/A0835451.html

- ^ https://www.rca.org/SSLPage.aspx?pid=6553

- ^ History of Awatovi. This section incorporates public domain text from this US government website.[which?]

- ^ Dee Brown, BURY MY HEART AT WOUNDED KNEE (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1991), 3-4.

- ^ William Cronon CHANGES IN THE LAND: INDIANS, COLONISTS, AND ECOLOGY OF NEW ENGLAND (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 1983), 165-170.

- ^ Carnes, Mark C.; John A. Garraty with Patrick Williams (1996). Mapping America's Past: A Historical Atlas. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 50. ISBN 0-8050-4927-4.

- ^ Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States, 2000. Collected by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB) and distributed by the Association of Religion Data Archives.

- ^ a b c d "Losing My Religion? No, Says Baylor Religion Survey". Baylor University. September 11, 2006. http://www.baylor.edu/pr/news.php?action=story&story=41678.

- ^ "5 Kinds of Christians — Understanding the disparity of those who call themselves Christian in America. Leadership Journal, Fall 2007.

- ^ a b "How many people go regularly to weekly religious services?". Religious Tolerance website. http://www.religioustolerance.org/rel_rate.htm.

- ^ "'One in 10' attends church weekly [3] publisher = BBC News".

- ^ [4] NCLS releases latest estimates of church attendance], National Church Life Survey, Media release,

- ^ San Diego Times, May 2, 2006, from 2006 Gallup survey

External links

Part of a series on Christianity Jesus Christ

Foundations Bible Theology Apologetics · Baptism · Christology · God · Father · Son · Holy Spirit · History of theology · Mary · Salvation · TrinityHistory and

traditionChurch Fathers · Early Christianity · Constantine · Ecumenical councils · Creeds ·

Missions · East–West Schism · Crusades · Protestant Reformation · ProtestantismDenominations

(List) and

MovementsWestern: Adventist · Anabaptist · Anglican · Baptist · Calvinism · Evangelical · Holiness ·

Independent Catholic · Lutheran · Methodist · Old Catholic · Pentecostal · Quaker · Roman Catholic

Eastern: Eastern Orthodox · Eastern Catholic · Oriental Orthodox (Miaphysite) · Assyrian

Nontrinitarian: Christadelphian · Jehovah's Witness · Latter Day Saint · Oneness Pentecostal · UnitarianTopics Art · Criticism · Ecumenism · Liturgical year · Liturgy · Music · Other religions · Prayer · Sermons · SymbolismDemographics of the United States Economic and social Affluence · Educational attainment · Emigration · Homeownership · Household income · Immigration · Income inequality · Language · LGBT · Middle classes · Personal income · Poverty · Social class · Unemployment by state · Wealth

Religion Race and ethnicity People of the United States/Americans · Ethnic groups in the United States · American people by ethnic or national origin · History of the United States by ethnic group · American culture by ethnicity · Race and ethnicity in the Census · Maps of American ancestries · 2010 Census · in the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission · Racism

White Americans (European Americans, Non-Hispanic Whites, White Hispanic and Latino Americans, Albanian Americans, Arab Americans, English Americans, German Americans, Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Polish Americans, etc.) · Black Americans (African Americans, Black Hispanic and Latino Americans, African immigrants and descendants, Afro-Caribbean/West Indian Americans, etc.) · Asian Americans (Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, Asian Hispanic and Latino Americans, Indian Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Japanese Americans, Pakistani Americans, etc.) · Hispanic and Latino Americans (Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans (Stateside), Cuban Americans, Colombian Americans, etc.) · Jewish Americans · Multiracial Americans · Native Americans and Alaska Natives · Pacific Islander Americans (Chamorro Americans, Native Hawaiians, Samoan Americans, etc.)

Christianity in North America Sovereign states Dependencies and

other territories- Anguilla

- Aruba

- Bermuda

- Bonaire

- British Virgin Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Curaçao

- Greenland

- Guadeloupe

- Martinique

- Montserrat

- Puerto Rico

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Martin

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saba

- Sint Eustatius

- Sint Maarten

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United States Virgin Islands

Categories:- Christianity in the United States

- Christianity in North America

- Religion in the United States

- Christianity by country

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.