- Classical Chinese

-

Classical Chinese / Literary Chinese 古文 / 文言 Spoken in mainland China; Taiwan; Japan; Korea and Vietnam Native speakers Not a spoken language (date missing) Language family Sino-Tibetan- Chinese

- Classical Chinese / Literary Chinese

Writing system Chinese Language codes ISO 639-3 lzh This page contains IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. Classical Chinese Chinese 古文 Literal meaning "ancient written language" Transcriptions Gan - Romanization gu3 mun4 Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin gǔwén Wu - Romanization ku ven Cantonese (Yue) - Jyutping gu2 man4 Literary Chinese Chinese 文言 Literal meaning "literary language" Transcriptions Gan - Romanization mun4 ngien4 Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin wényán Min - Hokkien POJ bûn-giân Wu - Romanization ven yie Cantonese (Yue) - Jyutping man4 jin4 Classical Chinese or Literary Chinese (文言文; pinyin: wényánwén) is a traditional style of written Chinese based on the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Chinese, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Classical Chinese was used for almost all formal correspondence in China until the early 20th century, and also, during various periods, in Korea, Japan and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Classical Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese (白話; pinyin: báihuà, "plain speech"), a style of writing that is similar to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese, while speakers of non-Chinese languages have largely abandoned Classical Chinese in favor of local vernaculars.

Literary Chinese is known as hanmun in Korean, kanbun in Japanese and Hán Văn in Vietnamese (From 漢文 in all three cases; pinyin: hànwén, "Han writing").

Contents

Definitions

While the terms Classical Chinese and Literary Chinese are often used interchangeably, Sinologists generally agree that they are in fact different.[1] "Classical" Chinese (古文; pinyin: gǔwén, "ancient writing") refers to the written language of China from the Zhou Dynasty, and especially the Spring and Autumn Period, through to the end of the Han Dynasty (AD 220). Classical Chinese is therefore the language used in many of China's most influential books, such as the Analects of Confucius, the Mencius and the Tao Te Ching. (The language of even older texts, such as the Classic of Poetry, is sometimes called Old Chinese, or pre-Classical.)

Literary Chinese (文言, pinyin: wényán, "literary speech"; in modern Chinese it additionally got a suffix 文, pinyin: wén that is used for written languages: 文言文) is the form of written Chinese used from the end of the Han Dynasty to the early 20th century when it was replaced by vernacular written Chinese. During this period the dialects of China became more and more disparate and thus the Classical written language became less and less representative of the spoken language. Although authors sought to write in the style of the Classics, the similarity decreased over the centuries due to their imperfect understanding of the older language, the influence of their own speech, and the addition of new words.

This situation, the usage of Literary Chinese throughout the Chinese cultural sphere despite the existence of disparate regional vernaculars, is called diglossia. It can be compared to the position of Classical Arabic relative to the various regional vernaculars in Arab lands, or of Latin in medieval Europe. The Romance languages continued to evolve, influencing Latin texts of the same period, so that by the Middle Ages, Medieval Latin included many usages that would have baffled the Romans. The coexistence of Classical Chinese and the native languages of Korea, Japan, and Vietnam can be compared to the use of Latin in countries that natively speak non-Latin-derived Germanic languages or Slavic languages, or to the position of Arabic in Persia and North India.

Pronunciation

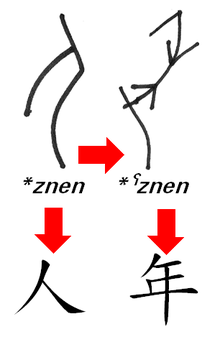

The shape of the Oracle bone script character for "person" may have influenced that for "harvest" (which later came to mean "year"). Today, they are pronounced rén and nián in Northern dialects, such as Mandarin. A hypothesized pronunciation for each character may explain the resemblance.

Chinese characters are not alphabetic and only palely reflect sound changes. The tentative reconstruction of Old Chinese is an endeavor only a few centuries old. As a result, Classical Chinese is not read with a reconstruction of Old Chinese pronunciation; instead, it is always read with the pronunciations of characters categorized and listed in the Phonology Dictionary (韻書; pinyin: yùnshū, "rhyme book") officially published by the Governments, originally based upon the Middle Chinese prounciation of Luoyang in the 2nd to 4th centuries. With the progress of time, every dynasty has updated and modified the official Phonology Dictionary. By the time of the Yuan Dynasty and Ming Dynasty, the Phonology Dictionary was based on early Mandarin. But since the Imperial Examination required the composition of Shi genre, in non-Mandarin speaking part of China such as Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian, pronunciation is either based on everyday speech as in Cantonese; or, in some varieties of Chinese (e.g. Southern Min), with a special set of pronunciations used for Classical Chinese or "formal" vocabulary and usage borrowed from Classical Chinese usage. In practice, all varieties of Chinese combine these two extremes. Mandarin and Cantonese, for example, also have words that are pronounced one way in colloquial usage and another way when used in Classical Chinese or in specialized terms coming from Classical Chinese, though the system is not as extensive as that of Southern Min or Wu.

Korean, Japanese, or Vietnamese readers of Classical Chinese use systems of pronunciation specific to their own languages. For example, Japanese speakers use On'yomi and (more rarely) Kun'yomi, which are the ways that kanji, or Chinese characters, are read when they are used to write in Japanese. Kunten, a system that aids Japanese speakers with Classical Chinese word order, was also used.

Since the pronunciation of all modern varieties of Chinese are different from Old Chinese or other forms of historical Chinese (such as Middle Chinese), characters that once rhymed in poetry may not rhyme any longer (e.g. rhyming occurs sometimes in Min or Cantonese but not as frequently in Mandarin), or vice versa. Poetry and other rhyme-based writing thus becomes less coherent than the original reading must have been. However, some modern Chinese languages have certain phonological characteristics that are closer to the older pronunciations than others, as shown by the preservation of certain rhyme structures. Some believe Classical Chinese literature, especially poetry, sounds better when read in certain languages believed to be closer to older pronunciations, such as Cantonese or Southern Min, because the rhyming is often lost due to sound shifts in Mandarin.

Another phenomenon that is common in reading Classical Chinese is homophony (words that sound the same). More than 2,500 years of sound change separates Classical Chinese from any modern language or dialect, so when reading Classical Chinese in any modern variety of Chinese (especially Mandarin) or in Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese, many characters which originally had different pronunciations have become homonyms. There is a famous Classical Chinese poem written in the early 20th-century by linguist Y. R. Chao called the Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den which contains only words that are now pronounced [ʂɨ́], [ʂɨ̌], [ʂɨ̀], and [ʂɨ̂] in Mandarin. It was written to show how Classical Chinese has become an impractical language for speakers of modern Chinese because Classical Chinese when spoken aloud is largely incomprehensible. However the poem is perfectly comprehensible when read silently because literary Chinese, by its very nature as a written language using a logographic writing system, can often get away with using homophones that even in spoken Old Chinese would not have been distinguishable in any way.

The situation is analogous to that of some English words that are spelled differently but sound the same, such as "meet" and "meat", which were pronounced [meːt] and [mɛːt] respectively during the time of Chaucer, as shown by their spelling. However, such homophones are far more common in Literary Chinese than in English. For example, 亦 "also", 弈 "Chinese chess", 意 "intention", 易 "exchange", "easy", 異 "different", 疫 "epidemic disease", 益 "profit", 義 "justice", 翌 "next", 藝 "art", "skill", and 邑 "city" are all [î] in Mandarin, but one reconstructed form of their pronunciations in Confucius's time is /lhiak/, /liak/, /ʔǝh/, /leh/, /Łǝh/, /wek/, /ʔek/, /ŋajh/, /Łǝk/, /ŋeć/, and /ʔǝp/ respectively[clarification needed].

Grammar and lexicon

Classical Chinese is distinguished from written vernacular Chinese in its style, which appears extremely concise and compact to modern Chinese speakers, and to some extent in the use of different lexical items (vocabulary). An essay in Classical Chinese, for example, might use half as many Chinese characters as in vernacular Chinese to relate the same content.

In terms of conciseness and compactness, Classical Chinese rarely uses words composed of two Chinese characters; nearly all words are of one syllable only. This stands directly in contrast with modern Chinese dialects, in which two-syllable words are extremely common. This phenomenon exists, in part, because polysyllabic words evolved in Chinese to disambiguate homophones that result from sound changes. This is similar to such phenomena in English as the pen–pin merger of many dialects in the American south: because the words "pin" and "pen" sound alike in such dialects of English, a certain degree of confusion can occur unless one adds qualifiers like "ink pen" and "stick pin." Similarly, Chinese has acquired many polysyllabic words in order to disambiguate monosyllabic words that sounded different in earlier forms of Chinese but identical in one region or another during later periods. Because Classical Chinese is based on the literary examples of ancient Chinese literature, it has almost none of the two-syllable words present in modern Chinese languages.

Classical Chinese has more pronouns compared to the modern vernacular. In particular, whereas Mandarin has one general character to refer to the first-person pronoun ("I"/"me"), Literary Chinese has several, many of which are used as part of honorific language (see Chinese honorifics), and several of which have different grammatical uses (first-person collective, first-person possessive, etc.).[citation needed]

In syntax, Classical Chinese is always ready to drop subjects, verbs, objects, etc. when their meaning is understood (pragmatically inferable). Also, words are not restrictively categorized into parts of speech: nouns used as verbs, adjectives used as nouns, and so on. There is no copula in Classical Chinese, "是" (pinyin: shì) is a copula in modern Chinese but in old Chinese it was originally a near demonstrative ("this"); the modern Chinese for "this" is "這" (pinyin: zhè).

Beyond grammar and vocabulary differences, Classical Chinese can be distinguished by literary and cultural differences: an effort to maintain parallelism and rhythm, even in prose works, and extensive use of literary and cultural allusions, thereby also contributing to brevity.

The Muslim Hui people developed Jingtang Jiaoyu for representing Arabic sounds with Chinese characters. Classical Chinese has had influence of Jingtang Jiaoyu.[clarification needed] Rather than using Standard Chinese grammar, they use the grammar of their dialect and Classical Chinese to read the Arabic sounds out loud.[clarification needed] The Classical Chinese word order is often the reverse of Mandarin; for example, Mandarin 饒恕 (pinyin: ráoshù, "forgive") is Classical 恕饒 (pinyin: shùráo).[2]

Teaching and use

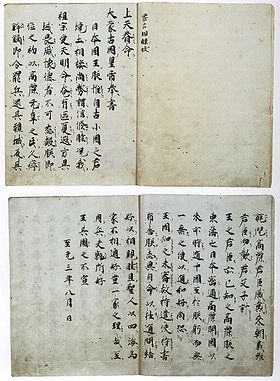

Classical Chinese was used in international communication between the Mongol Empire and Japan. This letter, dated 1266, was sent from Khubilai Khan to the "King of Japan" (日本國王) before the Mongol invasions of Japan; it was written in Classical Chinese. Now stored in Todai-ji, Nara, Japan.

Classical Chinese was used in international communication between the Mongol Empire and Japan. This letter, dated 1266, was sent from Khubilai Khan to the "King of Japan" (日本國王) before the Mongol invasions of Japan; it was written in Classical Chinese. Now stored in Todai-ji, Nara, Japan.

Classical Chinese was the main form used in Chinese literary works until the May Fourth Movement, and was also used extensively in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum proclamation in which the modern Korean alphabet (hangul) was promulgated and the essay by Hu Shi in which he argued against using Classical Chinese and in favor of written vernacular Chinese. (The latter parallels the essay written by Dante in Latin in which he expounded the virtues of the vernacular Italian.) Exceptions to the use of Classical Chinese were vernacular novels such as Dream of the Red Chamber, which was considered "vulgar" at the time.

Most government documents in the Republic of China were written in Classical Chinese until reforms in the 1970s, in a reform movement spearheaded by President Yen Chia-kan to shift the written style to vernacular Chinese.[3][4]

Today, pure Classical Chinese is occasionally used in formal or ceremonial occasions. Buddhist texts, or sutras, are still preserved in Classical Chinese from the time they were composed or translated from Sanskrit sources. In practice there is a socially accepted continuum between vernacular Chinese and Classical Chinese. For example, most notices and formal letters are written with a number of stock Classical Chinese expressions (e.g. salutation, closing). Personal letters, on the other hand, are mostly written in vernacular, but with some Classical phrases, depending on the subject matter, the writer's level of education, etc. Letters or essays written completely in Classical Chinese today may be considered quaint, old-fashioned or even pretentious by some, but may seem impressive to others.[citation needed]

Most Chinese people with at least a middle school education are able to read basic Classical Chinese, because the ability to read (but not write) Classical Chinese is part of the Chinese middle school and high school curricula and is part of the college entrance examination. Classical Chinese is taught primarily by presenting a classical Chinese work and including a vernacular gloss that explains the meaning of phrases. Tests on classical Chinese usually ask the student to express the meaning of a paragraph in vernacular Chinese, using multiple choice. They often take the form of comprehension questions.

In addition, many works of literature in Classical Chinese (such as Tang poetry) have been major cultural influences. However, even with knowledge of grammar and vocabulary, Classical Chinese can be difficult to understand by native speakers of modern Chinese, because of its heavy use of literary references and allusions as well as its extremely abbreviated style.

See also

- Chinese language

- Classical Chinese grammar

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese Wikipedia

- Classical Chinese writers

- Sino-Japanese vocabulary

- Sino-Korean vocabulary

- Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary

Further reading

- Abel Rémusat (1822). Élémens de la grammaire chinoise, ou, Principes généraux du kou-wen ou style antique: et du kouan-hoa c'est-à-dire, de la langue commune généralement usitée dans l'Empire chinois. PARIS: Imprimerie Royale. pp. 214. http://books.google.com/books?id=rJAUAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-15. (Original from Harvard University)

- Frederick William Baller, China Inland Mission (1912). Lessons in elementary Wen-li. China Inland Mission. pp. 128. http://books.google.com/books?id=7bNDAAAAIAAJ&dq=zung+kuh++soo+kyi+tok&q=mandarin. Retrieved 2011-05-15. (Original from the University of California)

- Herrlee Glessner Creel, ed (1952). Literary Chinese by the inductive method, Volume 2. University of Chicago Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=Eq9hAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2011-05-15. (Original from the University of Michigan)

References

- ^ Jerry Norman (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0521296536.

- ^ Maris Boyd Gillette (2000). Between Mecca and Beijing: modernization and consumption among urban Chinese Muslims. Stanford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0804736944. http://books.google.com/books?id=b21aKLh6_KkC&pg=PA242&dq=jingtang+jiaoyu+an+la+hu#v=onepage&q=jingtang%20jishu%20god&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ Baldauf, Richard B.; Robert B. Kaplan (2000). Language planning in Nepal, Taiwan, and Sweden. 115. Multilingual Matters. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9781853594830.

- ^ Cheong, Ching (2001). Will Taiwan break away: the rise of Taiwanese nationalism. World Scientific. pp. 187. ISBN 9789810244866.

External links

- Chinese Text Project Classical Chinese texts with English translations and classical Chinese dictionary

- headpage Classical Chinese Wikipedia

Chinese language(s) Major

subdivisionsNortheastern · Ji-Lu · Jiao-Liao · Zhongyuan · Southwestern · Lan-Yin · Lower Yangtze · Beijing · Dungan · Xuzhou · Luoyang · Jinan · Karamay · Nanking · Sichuanese · Kunming · Shenyang · Harbin · Qingdao · Guanzhong · Dalian · Weihai · Taiwanese Mandarin · Filipino-Mandarin · Malaysian Mandarin · Singaporean Mandarin · Chuan-puYueother MinDisputedUnclassifiedStandardized forms

(Ausbausprache)Phonology History Written Chinese OfficialHistorical scriptsOtherList of varieties of ChineseCategories:- Language articles with undated speaker data

- Chinese language

- Classical languages

- Korean language

- Japanese language

- Vietnamese writing systems

- Chinese

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.