- Varieties of Chinese

-

Chinese Geographic

distribution:mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore and other areas with historic immigration from China. Linguistic classification: Sino-Tibetan - Sinitic

- Chinese

Subdivisions: Ba-Shu †Yue–Ping

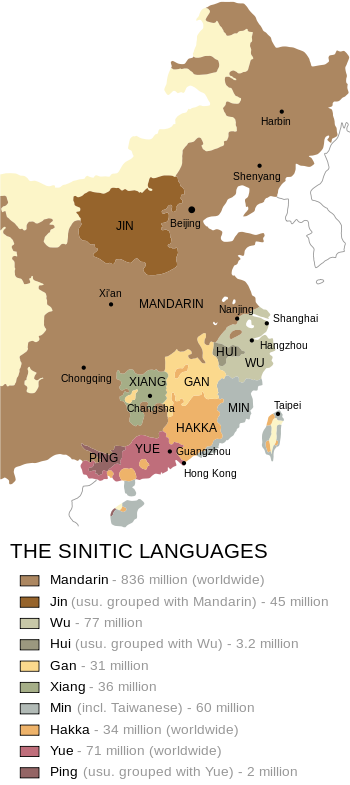

Primary branches of Chinese spoken in areas claimed by the People's Republic of China.Chinese (hànyǔ 汉语/漢語 or zhōngguóhuà 中国话/中國話) comprises many regional language varieties sometimes grouped together as the Sinitic languages, the primary ones being Mandarin, Wu, Cantonese, and Min. These are not mutually intelligible, and even many of the regional varieties (especially Min) are themselves composed of a number of non-mutually-intelligible subvarieties. As a result, Western linguists typically refer to these varieties as separate languages. For sociological and political reasons, however, most Chinese speakers and Chinese linguists consider them to be variations of a single Chinese language, and refer to them as dialects, translating the Chinese terms huà 话, yǔ 語, and fāngyán 方言. The neologism topolect has been coined as a more literal translation of fangyan in order to avoid the connotations of the term "dialect" (which in its normal English usage suggests mutually intelligible varieties of a single language), and to make a clearer distinction between "major varieties" (separate languages, in Western terminology) and "minor varieties" (dialects of a single language). In this article, however, the generic term "variety" will be used.

Chinese people make a strong distinction between written language (文, Pinyin: wén) and spoken language (语/語 yǔ). English does not necessarily have this distinction. As a result the terms Zhongwen (中文) and Hanyu (汉語/漢語) in Chinese are both translated in English as "Chinese". Within China, it is common perception that these varieties are distinct in their spoken forms only, and that the language, when written, is common across the country.

Contents

Classification

Main article: List of Chinese dialectsChinese consists of several dialect continuums. Differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, with few radical breaks. However, the degree of change in intelligibility varies immensely depending on region. For example, the varieties of Mandarin spoken in all three northeastern Chinese provinces are mutually intelligible, but in the small province of Zhejiang a person from one valley may be completely unable to comprehend the language from the next, though both are considered dialects of Wu Chinese.

In the book, "The Middle kingdom: a survey of the ... Chinese empire and its inhabitants ...", published in 1848, the different varieties of Chinese were described as "dialects", the book acknowledged that they were mutually unintelligible and the term "dialect" was used in a different sense than the western term, in which a dialect was merely indicative of a small difference in pronunciation, while in China, the entire grammar and idiom were different, the written language was what united the different Chinese dialects.[1]

Mandarin (Standard Chinese) is the dominant variety, much more widely studied than the rest. Outside of China, the only two varieties commonly presented in formal courses are Mandarin and Cantonese. Inside China, second-language acquisition is generally achieved through immersion in the local language.

The scientific classification of Chinese into different regional dialects is very recent. The first such efforts were made by Fang-kuei Li in 1937, which, with only minor modifications, form the basis for the current, conventionally accepted set of seven dialect groups:[2]

Phylogenetic classification Chinese Guan Mandarin Jianghuai Mandarin

Lanyin Mandarin

? Wu Taizhou

Wuzhou

Xuanzhou

Xiang Min Min Bei Shaojiang

Min Nan Qiongwen Leizhou

Pinghua

Yue Yuehai Tanka

Sanyi

Zhongshan

Luoguang

Guinan

? Tuhua

Ba-Shu †

- Mandarin 官话/官話 (also Northern 北方話/北方话): (c. 836 million speakers) This is the group of dialects spoken in northern and southwestern China, and makes up the largest spoken language in China. Standard Chinese, called Putonghua or Guoyu in Chinese, which is often also translated as "Mandarin" or simply "Chinese", belongs to this group. It is the official spoken language of the People's Republic of China, and Singapore. Mandarin Chinese is also the official language of the Republic of China governing Taiwan, although there are minor differences in this standard from the form standardized in the PRC.[3]

- Wu 吴语/吳語: (c. 77 million) spoken in the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, and the municipality of Shanghai. Wu includes Shanghai dialect, sometimes taken as the representative of all Wu dialects. Wu's subgroups are extremely diverse, especially in the mountainous regions of Zhejiang and eastern Anhui. The group possibly comprises hundreds of distinct spoken forms which are not mutually intelligible. Wu is notable among Chinese dialects in having kept "voiced" (actually slack voiced) initials, such as /b̥/, /d̥/, /ɡ̊/, /z̥/, /v̥/, /d̥ʑ̊/, /ʑ̊/ etc.

- Yue (Cantonese) 粤语/粵語: (c. 71 million) spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau, parts of Southeast Asia and by Overseas Chinese with an ancestry tracing back to the Guangdong region. The term "Cantonese" may cover all the Yue dialects, including Taishanese, or specifically the Canton dialect of Guangzhou and Hong Kong. Not all varieties of Yue are mutually intelligible. Yue retains the full complement of Middle Chinese word-final consonants (p, t, k, m, n, ng), and has a well-developed inventory of tones.

- The Min languages 闽语/閩語: (c. 60 million) spoken in Fujian, Taiwan, parts of Southeast Asia particularly Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore, and among Overseas Chinese who trace their roots to Fujian and Taiwan, particularly prevalently in New York City in the United States. The largest Min language is Hokkien, which is spoken in Southern Fujian, Taiwan, and by many Chinese in Southeast Asia and includes the Taiwanese, and Amoy dialects amongst others. Min is the only branch of Chinese that cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese. It is also the most diverse, divided into seven subgroups defined on the basis of relative mutual intelligibility: Min Nan (which includes Hokkien and Teochew), Min Dong (which includes the Fuzhou dialect), Min Bei, Min Zhong, Pu Xian, Qiong Wen, and Shao Jiang.

- Xiang (Hunanese) 湘语/湘語:(c. 36 million) spoken in Hunan. Xiang is usually divided into the "old" and "new" dialects, with the new dialects being significantly influenced by Mandarin.[citation needed]

- Hakka 客家话/客家話: (c. 34 million) spoken by the Hakka people, a cultural group of the Han Chinese, in several provinces across southern China, in Taiwan, and in parts of Southeast Asia such as Malaysia and Singapore. The term "Hakka" itself translates as "guest families", and many Hakka people consider themselves to be descended from Song-era and later refugees from North China, although their genetic origin is still disputed. Hakka has kept many features of northern Middle Chinese that have been lost in the North. It also has a full complement of nasal endings, -m -n -ŋ and occlusive endings -p -t -k, maintaining the four categories of tonal types, with splitting in the ping and ru tones, giving six tones. Some dialects of Hakka have seven tones, due to splitting in the qu tone. One of the distinguishing features of Hakka phonology is that Middle Chinese voiced initials are transformed into Hakka voiceless aspirated initials.

- Gan 赣语/贛語: (c. 31 million) spoken in Jiangxi. In the past, it was viewed as closely related to Hakka dialects, because of the way Middle Chinese voiced initials have become voiceless aspirated initials, as in Hakka, and were hence called by the umbrella term "Hakka-Gan dialects".

Ba-Shu, of Sichuan, was one of the most divergent varieties of Chinese. However, it was supplanted by Southwestern Mandarin during the Ming dynasty.

There is some dispute as to whether the following varieties should be classified separately:

- Huizhou 徽语/徽語: (c. 3.2 million) spoken in the southern parts of Anhui—formerly, and sometimes still, classified as a dialect of Wu, now classified as an independent dialect.

- Jin 晋语/晉語: spoken in Shanxi, as well as parts of Shaanxi, Hebei, Henan, and Inner Mongolia. Often classed as dialect of Mandarin.

- Pinghua 平话/平話: (c. 2 million) spoken in parts of the Guangxi. Sometimes classed as dialect of Cantonese.

Some varieties remain unclassified. These include:

- Danzhou dialect 儋州话/儋州話: spoken in Danzhou, Hainan.

- Xianghua 乡话/鄉話: spoken in a small strip of land in western Hunan, this group of dialects has not been conclusively classified.

- Shaozhou Tuhua 韶州土话/韶州土話: spoken at the border regions of Guangdong, Hunan, and Guangxi. This is an area of great linguistic diversity, and has not yet been conclusively described or classified.

In addition, the Dungan language (东干语/東干語) is a dialect of Mandarin spoken in Kyrgyzstan. However, it is written in the Cyrillic alphabet as a result of Soviet rule.

Quantitative similarity

A 2007 study compared 15 major urban dialects on two objective and two subjective criteria:[4]

- Lexical similarity

- Phonological regularity (regularity of sound correspondences, not direct phonological similarity)

- Subjective intelligibility

- Subjective similarity

Major north+central vs. south split

- Generally the top-level split put Northern, New Xiang, and Gan in one group and Min (samples at Fuzhou, Xiamen, Chaozhou), Hakka, and Yue in the other group, except for phonological regularity, where the one Gan dialect (Nanchang) was in the Southern group and very close to Hakka, and the deepest phonological difference was between Wenzhounese (the southernmost Wu dialect) and all other dialects.

Lack of clear splits within the north+central area

- Changsha (New Xiang) was always within the Mandarin group. No Old Xiang dialect was in the sample.

- Taiyuan (Jin or Shanxi) and Hankou (Wuhan, Hubei) were subjectively perceived as relatively different from other Northern dialects, but were very close in subjective intelligibility. Objectively, Taiyuan had substantial phonological divergence but little lexical divergence.

- Chengdu (Sichuan) was somewhat divergent lexically, but very little on the other measures.

Intermediate position of Wu, and unintelligibility of Wenzhounese

- The two Wu dialects were closer to the Northern/New Xiang/Gan group in lexical similarity and strongly closer in subjective intelligibility, but closer to Min/Hakka/Yue in phonological regularity and subjective similarity, except that Wenzhou was farthest from all other dialects in phonological regularity. The two Wu dialects were close to each other in lexical similarity and subjective similarity, but not in subjective intelligibility, where Suzhou was actually closer to Northern/Xiang/Gan than to Wenzhou.

High divergence within Min

- Fuzhou (Eastern Min) grouped only weakly with the Southern Min dialects Xiamen and Chaozhou on the two objective criteria, and was actually slightly closer to Hakka and Yue on the subjective criteria.

Closeness of the southernmost dialect areas

- Hakka and Yue grouped closely together on the three lexical and subjective measures, but not in phonological regularity.

Local classifications

Generally, when referring to a local dialect in everyday speech, the speaker will refer to the dominant city in the region as a marker of the dialect as a whole. For example, a Wu speaker would not ask a fellow Wu speaker if they speak "Wu", but would rather ask whether or not they speak the dialect from Suzhou or Hangzhou, known as Suzhouhua and Hangzhouhua, respectively, in Chinese. Generally dialects are branded according to cities, geographical regions, or provinces. This method of informal classification is commonly used in spoken language. Provinces whose dialects are more homogeneous within its boundaries, such as Shaanxi, Shanxi, Shandong, Hebei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, etc. tend to refer to their own dialects by the name of the province (although sub-dialects exist and can be referred to locally by the name of a city). In more diverse provinces such as Fujian, dialects are informally classified by mutual intelligibility into Min Nan (闽南话), Min Dong (闽东话), and Min Bei (闽北话); in Zhejiang, where there is vast variance in spoken language, dialects are generally classified by cities or counties – as such, no singular "Zhejiang dialect" exists. An area with widespread homogeneity in spoken language is the three provinces of Northeastern China, whose spoken language is collectively known as Northeastern Mandarin, or Dongbei Hua (东北话) in Chinese.

Sociolinguistics

Bilingualism with the standard language

In southern China (not including Hong Kong and Macau), where the difference between Standard Chinese and local dialects are particularly pronounced, well-educated Chinese are generally fluent in Standard Chinese[citation needed], and most people have at least a good passive knowledge of it[citation needed], in addition to being native speakers of the local dialect. The choice of dialect varies based on the social situation. Standard Chinese is usually considered more formal and is required when speaking to a person who does not understand the local dialect. The local dialect (be it nonStandard Chinese or non-Mandarin altogether) is generally considered more intimate and is used among close family members and friends and in everyday conversation within the local area. Chinese speakers will frequently code switch between Standard Chinese and the local dialect. Parents will generally speak to their children in dialect, and the relationship between dialect and Mandarin appears to be mostly stable. Local languages give a sense of identity to local cultures.

Knowing the local dialect is of considerable social benefit and most Chinese who permanently move to a new area will attempt to pick up the local dialect. Learning a new dialect is usually done informally through a process of immersion and recognizing sound shifts. Generally the differences are more pronounced lexically than grammatically. Typically, a speaker of one dialect of Chinese will need about a year of immersion to understand the local dialect[citation needed] and about three to five years to become fluent in speaking it[citation needed]. Because of the variety of dialects spoken, there are usually few formal methods for learning a local dialect.

Due to the variety in Chinese speech, Mandarin speakers from each area of China are very often prone to fuse or "translate" words from their local tongue into their Mandarin conversations. In addition, each area of China has its recognizable accents while speaking Mandarin. Generally, the nationalized standard form of Mandarin pronunciation is only heard on news and radio broadcasts. Even in the streets of Beijing, the flavour of Mandarin varies in pronunciation from the Mandarin heard on the media.

Political issues

During the Qing dynasty, knowledge of Mandarin (kwan hwa) was required by anyone who pursued an education in China, and was the official language. The Mandarin of the capital was considered standard, and variants of it existed in Henan, Shandong, and Anhui.[5]

Within mainland China, there has been a persistent drive towards promoting the standard language (大力推广普通话 dàlì tuīguǎng Pǔtōnghuà); for instance, the education system is entirely Mandarin-medium from the second year onwards. However, usage of local dialect is tolerated, and in many informal situations socially preferred. In Hong Kong, colloquial Cantonese characters are never used in formal documents, other than quoting witnesses' spoken statements during legal trials, and within the PRC a character set closer to Mandarin tends to be used. At the national level, differences in dialect generally do not correspond to political divisions or categories, and this has for the most part prevented dialect from becoming the basis of identity politics. Historically, many of the people who promoted Chinese nationalism were from southern China and did not natively speak the national standard language, and even leaders from northern China rarely spoke with the standard accent. For example, Mao Zedong often emphasized his Hunan origins in speaking, rendering much of what he said incomprehensible to many Chinese. One consequence of this is that China does not have a well-developed tradition of spoken political rhetoric, and most Chinese political works are intended primarily as written works rather than spoken works.

Another factor that limits the political implications of dialect is that it is very common within an extended family for different people to know and use different dialects. In addition, while speaking similar dialect provides very strong group identity at the level of a city or county, the high degree of linguistic diversity limits the amount of group solidarity at larger levels. Finally, the linguistic diversity of southern China makes it likely that in any large group of Chinese, Mandarin will be the only form of speech that everyone understands.

On the other hand in Taiwan, the government had a policy of promoting Mandarin over the local languages, such as Taiwanese and Hakka. This policy was implemented rigidly when Mandarin was the only language of instruction in schools, while English was offered as the compulsory second language. Since late 1990s, other languages have also been offered as a second language.

Examples of variations

The Min languages are often regarded as furthest removed linguistically from Standard Chinese, in phonology, grammar, and vocabulary. Historically, the Min languages were the first to diverge from the rest of the Chinese languages; see the discussion of historical Chinese phonology for more details. (The Min languages are also the group with the greatest amount of internal diversity, and are often regarded as consisting of at least five separate languages, e.g. Northern Min, Southern Min, Central Min, Eastern Min and Puxian Min.)

To illustrate: In Taiwanese, a variety of Hokkien, a Min language, to express the idea that one is feeling a little ill ("I am not feeling well."), one might say (in Pe̍h-oē-jī):

Goá kā-kī lâng ū tām-po̍h-á bô sóng-khoài.

我家己人有淡薄無爽快。(我家己人有淡薄无爽快)which, when translated cognate-by-cognate into Mandarin would be spoken as an awkward or semantically unrecognizable sentence:

Wǒ jiājǐ rén yǒu dànbó wú shuǎngkuài.

Could roughly be interpreted as:

My family's own person is weakly not feeling refreshed.Whereas when spoken colloquially in Mandarin, one would either say:

Wǒ zìjǐ yǒu yīdiǎn bù shūfu.

我自己有一點不舒服。(我自己有一点不舒服)

I myself feel a bit uncomfortable.or:

Wǒ yǒu yīdiǎn bù shūfu.

我有一點不舒服。(我有一点不舒服)

I feel a bit uncomfortable.the latter omitting the reflexive pronoun (zìjǐ), not usually needed in Mandarin.

Some people, particularly in northeastern China, would say:

Wǒ yǒu diǎnr bù shūfu.

我有點兒不舒服。(我有一点儿不舒服)

Literally: I am [a] bit[DIM.] uncomfortable.Comparison of vocabulary

[Wu, Xiang, Gan, Min Nan missing tone]

Differences in the socio-political context of Chinese and European languages gave rise to the difference in terms of linguistic perception between the two cultures. In Western Europe, Latin remained the written standard for centuries after the spoken language diverged and began shifting into distinct Romance languages, and similarly Classical Chinese remained the written standard while dialects of Old Chinese and Middle Chinese diverged. Latin, however, was eventually revived as a spoken language as well (Medieval Latin), and political fragmentation gave rise to independent states roughly the size of Chinese provinces, which eventually generated a political desire to create separate cultural and literary standards to differentiate nation-states and standardize the language within a nation-state. But in China, the cultural standard of Classical Chinese (and later, Vernacular Chinese) remained a purely literary language, while the spoken language continued to diverge between different cities and counties, much as European languages diverged, due to the scale of the country, and the obstruction of communication by geography.

The diverse Chinese spoken forms and common written form comprise a very different linguistic situation from that in Europe. In Europe, linguistic differences sharpened as the language of each nation-state was standardized. The use of local speech became stigmatized. In China, standardization of spoken languages was weaker, but they continued to be spoken, with written Classical Chinese read with local pronunciation. Although, as with Europe, dialects of regional political or cultural capitals were still prestigious and widely used as the region's lingua franca, their linguistic influence depended more on the capital's status and wealth than entirely on the political boundaries of the region.

The following table was transliterated using the International Phonetic Alphabet. The forms account for lexical (writing) differences in addition to phonological (sound) differences. For example, the Mandarin word for the pronoun "s/he" is 他 /tʰa˥/; but in Cantonese (Yue) a different word, 佢 is used.

English Mandarin Wu Xiang Gan Hakka Yue Minnan French Italian Catalan Spanish Portuguese Romanian I uɔ˨˩˦ ŋu ŋo ŋo ŋai˩ ŋɔː˩˧ ɡua je io jo yo eu eu you ni˨˩˦ noŋ n̩ n̩ n˩, nʲi˩ nei˩˧ li tu tu tu tú tu tu (s)he tʰa˥ ɦi tʰa tɕiɛ kʰi˩, ki˩ kʰɵy˩˧ i il/elle egli/lui ell él/ella ele/ela el this tʂɤ˥˩ ɡəʔ ko ko e˧˩, nʲia˧˩ niː˥ tɕɪt ceci questo aquest este este acesta that na˥˩ ɛ la hɛ ke˥˧ kɔː˧˥ he cela quello aqueix aquel aquele acela human ʐən˧˥ ɳin zən ɳin nʲin˩ jɐn˨˩ laŋ homme uomo home hombre homem om man nan˧˥ nø lan lan nam˩ naːm˨˩ lam homme uomo home hombre homem bărbat woman ny˨˩˦ ɳy ɳy ɳi ŋ˧˩, nʲi˧˩ nɵy˩˧ li femme donna dona mujer mulher femeie father pa˥˩pa˩ ɦia ia ia a˦ pa˦ paː˥ lau pe père padre pare padre pai tată mother ma˥ma˨ ɳiã m ma ɳiɔŋ a˦ me˦ maː˥ lau bo mère madre mare madre mãe mamă child ɕiɑʊ˩xai˧˥ ɕiɔ nø ɕi ŋa tsɨ ɕi ŋa tsɨ se˥˧˥ nʲin˩ e˧ sɐi˧ lou˨ ɡɪn a enfant bambino nen niño criança copil fish y˧˥ ɦŋ y ɳiɛ ŋ˩ e˧ jyː˨˩ hi poisson pesce peix pez peixe peşte snake ʂɤ˧˥ zo sə sa sa˩ sɛː˨˩ tsua serpent serpente serp serpiente serpente şarpe meat ʐɤʊ˥˩ ɳioʔ zəu ɳiuk nʲiuk˩ jʊk˨ baʔ viande carne carn carne carne carne bone ku˨˩˦ kuəʔ ku kut kut˩ kʷɐt˥ kut os osso os hueso osso os eye iɛn˨˩˦ ŋɛ ŋan ŋan muk˩, ŋan˧˩ ŋaːn˩˧ bak œil occhio ull ojo olho ochi ear ɑɻ˨˩˦ ɳi ə o nʲi˧˩ jiː˩˧ hĩ oreille orecchio orella oreja orelha ureche nose pi˧˥ biɪʔ pi pʰit pʰi˥˧ pei˨ pʰĩ nez naso nas nariz nariz nas to eat tʂʰɨ˥ tɕʰiɪʔ tɕʰia tɕʰiak sɨt˥ sɪk˨ tɕiaʔ manger mangiare menjar comer comer a mânca to drink xɤ˥ xaʔ tɕʰia tɕʰiak sɨt˥, jim˧˩ jɐm˧˥ lɪm boire bere beure beber beber a bea to say ʂuɔ˥ kã kan ua ʋa˥˧, ham˥˧, kɔŋ˧˩ kɔːŋ˧˥ kɔŋ dire dire dir decir dizer a zice to hear tʰiŋ˥ tin tʰin tʰiaŋ tʰaŋ˥˧ tʰɛːŋ˥ tʰiã entendre udire/sentire sentir oír ouvir a auzi to see kʰan˥˩ kʰɤ uan mɔŋ kʰon˥˧ tʰɐi˧˥ kʰuã voir vedere veure ver ver a vedea to smell uən˧˥ mən uən ɕiuŋ ʋun˩, pʰi˥˧ mɐn˨˩ pʰĩ sentir odorare sentir oler cheirar a mirosi to sit tsuɔ˥˩ zu tso tsʰo tsʰɔ˦ tsʰɔː˩˧ tse s'asseoir sedere assentar-se sentarse sentar-se a şedea to be lying down tʰɑŋ˨˩˦ kʰuən tʰan kʰun min˩, sɔi˥˧, tʰoŋ˧˩ fɐn˧ to s'étendre distendersi estirar-se tenderse deitar-se a sta culcat to stand tʂan˥ liɪʔ tsan tɕʰi kʰi˦ kʰei˩˧ kʰia être debout stare in piedi estar de peu estar de pie estar de pé a sta în picioare sun tʰai˥˩iɑŋ˧˥ ɳiɪʔ dɤ tʰai ian ɳit tʰɛu nʲit˩ tʰɛu˩ jɐt˩ tʰaːu˧˥, tʰaːi˧ jœːŋ˨˩ lɪt tʰau soleil sole sol sol sol soare moon yœ˥˩liɑŋ˩ ɦyɪʔ liã ye lian ɳiot kuɔŋ nʲiet˥ kuɔŋ˦ jyːt˨ kʷɔːŋ˥ ɡeʔ niu lune luna lluna luna lua lună mountain ʂɑn˥ sɛ san san san˦ saːn˥ suã montagne montagna muntanya montaña montanha munte water ʂuei˨˩˦ sɨ ɕyei sui sui˧˩ sɵy˧˥ tsui eau acqua aigua agua água apă red xʊŋ˧˥ ɦoŋ xən fuŋ fuŋ˩ hʊŋ˨˩ aŋ rouge rosso vermell rojo vermelho roşu green ly˥˩ loʔ ləu liuk liuk˥, tsʰiaŋ˦ lʊk˨ lɪk vert verde verd verde verde verde yellow xuɑŋ˧˥ uã uan uɔŋ ʋoŋ˩ wɔːŋ˨˩ ŋ jaune giallo groc amarillo amarelo galben white pai˧˥ bɐʔ pə pʰak pʰak˥ paːk˨ peʔ blanc bianco blanc blanco branco alb black xei˥ həʔ xə hɛt ʋu˦ hɐk˥ ɔ noir nero negre negro negro negru daytime pai˧˥tʰiɛn˥ ɳiɪʔ ɕiã pə tʰiẽ ɳit sɔŋ nʲit˩ sɨn˩ tʰeu˩ jɐt˨ tʰɐu˧˥ dʒɪt ɕi jour giorno dia día dia zi night iɛ˥˩uan˨˩˦ ɦia li uan san ia li am˥˧ pu˦ tʰeu˩,

am˥˧ pu˦ sɨn˩jɛː˨ maːn˩˧ am ɕi nuit notte nit noche noite noapte Mandarin Wu Xiang Gan Hakka Yue Minnan French Italian Catalan Spanish Portuguese Romanian Shanghainese pronunciation used for Wu Chinese.

Comparison of tone

The number of tones in a particular variety is often counted differently in traditional Chinese grammar and in modern linguistics. This is because the four tones of Chinese grammar originally reflected final consonants rather than tone in the English sense of the word (i.e. "entering tones"), as well as tone splits which are still allophonic in for example the Wu dialects. Thus Shanghainese has five 声 shēng (phonetically distinguishable tones) but only two tonemes (phonemically distinct tones).

See four tones for coverage of the correspondences between the tones of the major varieties of Chinese.

Phonology

The phonological structure of each syllable consists of a nucleus consisting of a vowel (which can be a monophthong, diphthong, or even a triphthong in certain varieties) with an optional onset or coda consonant as well as a tone. There are some instances where a non-vowel is used as a nucleus. An example of this is in Cantonese, where the nasal sonorant consonants /m/ and /ŋ/ can stand alone as their own syllable.

Across all the spoken varieties, most syllables tend to be open syllables, meaning they have no coda, but syllables that do have codas are restricted to /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /p/, /t/, /k/, or /ʔ/. Some varieties allow most of these codas, whereas others, such as Mandarin, are limited to only two, namely /n/ and /ŋ/. Consonant clusters do not generally occur in either the onset or coda. The onset may be an affricate or a consonant followed by a semivowel, but these are not generally considered consonant clusters.

The number of sounds in the different spoken dialects varies, but in general there has been a tendency to a reduction in sounds from Middle Chinese. The Mandarin dialects in particular have experienced a dramatic decrease in sounds and so have far more multisyllabic words than most other spoken varieties. The total number of syllables in some varieties is therefore only about a thousand, including tonal variation.

All varieties of spoken Chinese use tones. A few dialects of north China may have as few as three tones, while some dialects in south China have up to 6 or 10 tones, depending on how one counts. One exception from this is Shanghainese, which has reduced the set of tones to a two-toned pitch accent system much like modern Japanese.

A very common example used to illustrate the use of tones in Chinese are the four main tones of Standard Chinese applied to the syllable ma. The tones correspond to these five characters:

Chinese tone usage common example Traditional hanzi Simplified hanzi Romanization Semantic Tone 媽 妈 mā "mother" high level 麻 má "hemp" high rising 馬 马 mǎ "horse" low falling-rising 罵 骂 mà "scold" high falling 嗎 吗 ma question particle neutral Historically, Middle Chinese had three tonal distinctions on most syllables. Checked syllables (those ending in a stop consonant /p/, /t/ or /k/) were toneless; however, traditional Chinese grammar counted these as a fourth tone (the so-called "entering tone"). During the Middle Chinese period, a tone split happened in most varieties as a result of two successive sound changes:

- Tones in syllables beginning with a voiced consonant were phonetically lowered in pitch.

- Except in Wu, voiced obstruents merged with voiceless ones but the lowered tones remained, doubling the number of phonemic tones.

This produced 6 phonemic tones, or 8 according to traditional Chinese classification. Cantonese maintains these tones, and has developed an additional distinction in checked syllables. However, most varieties have reduced the number of tonal distinctions. For example, in Mandarin, the tones resulting from the split of Middle Chinese tones 2 and 3 merged, leaving 4 tones. Furthermore, Mandarin final stop consonants disappeared, and such syllables were reassigned to one of the other 4 tones.

In Wu, voiced obstruents were retained, and the tone split never became phonemic: the higher-pitched allophones occur with initial voiceless consonants, and the lower-pitched allophones occur with initial voiced consonants. (Traditional Chinese classification nonetheless counts these as different tones.) Most Wu dialects retain the three tones of Middle Chinese, and some have developed additional distinctions. However, in Shanghainese one of these merged with the other two, and these two merged in syllables with initial voiced consonants. In addition, in polysyllabic words, the tone of all other syllables is determined by the tone of the first: Shanghainese has word rather than syllable tone. The result is that there are only two phonemic tones in Shanghainese, and those only in words beginning with a voiceless stop and whose first syllables do not end in a stop. Other words have no phonemic tonal distinctions.

See also

- Languages of China

- List of Chinese dialects

- The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy

- A language is a dialect with an army and navy

References

Footnotes

This article incorporates text from The Middle kingdom: a survey of the ... Chinese empire and its inhabitants ..., by Samuel Wells Williams, a publication from 1848 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Middle kingdom: a survey of the ... Chinese empire and its inhabitants ..., by Samuel Wells Williams, a publication from 1848 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ Samuel Wells Williams (1848). The Middle kingdom: a survey of the ... Chinese empire and its inhabitants .... Volume 1 of The Middle kingdom: a survey of the geography, government, education, social life, arts, religion, &c., of the Chinese empire and its inhabitants (3 ed.). New York: Wiley & Putnam. p. 488. http://books.google.com/?id=Pk0UAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=snippet&q=dialect%20in%20languages%20usually%20described&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-08.(Original from Harvard University)

- ^ A Critical Review of Norman's Chinese Marjorie K.M. Chan and James H.Y. Tai

- ^ For example, in the Republic of China, malingshu (tone?) is used to denote "potato" while in the mainland, the People's Republic of China, tudou (tone?) is used to denote "potato".

- ^ Chaoju Tang and Vincent J. Van Heuven, “Predicting mutual intelligibility in chinese dialects from subjective and objective linguistic similarity”

- ^ Samuel Wells Williams (1848). The Middle kingdom: a survey of the ... Chinese empire and its inhabitants .... Volume 1 of The Middle kingdom: a survey of the geography, government, education, social life, arts, religion, &c., of the Chinese empire and its inhabitants (3 ed.). New York: Wiley & Putnam. p. 489. http://books.google.com/?id=Pk0UAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=mandarin%20dialect&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-08.(Original from Harvard University)

Notations

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology – the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 31-101-5831-0.

- DeFrancis, John. 1990. The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1068-6

- Hannas, William. C. 1997. Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1892-X (paperback); ISBN 0-8248-1842-3 (hardcover)

- Groves, Julie M. (2008). "Language or Dialect – or Topolect? A Comparison of the Attitudes of Hong Kongers and Mainland Chinese towards the Status of Cantonese". Sino-Platonic Papers 179: 1–103. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp179_cantonese.pdf.

- Mair, Victor H. (1991). "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms". Sino-Platonic Papers 29: 1–31. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp029_chinese_dialect.pdf.

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29653-6.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01468-X.

External links

- Popup Chinese podcasts and lessons in the Standard Chinese dialect, with others dialogues covering a wide range of alternate regional dialects including Hangzhouhua, Shanghaihua, Beijinghua and Guangdonghua.

- Learn Cantonese (with Cantonese–English / English–Cantonese Dictionary)

- Open Source Chinese–English Dictionary including a user-editable online interface, downloadable software and dictionary package, and online community of translators and students.

- Details on many Chinese Dialects (e.g. Classification)

- Technical Notes on the Chinese Language Dialects, by Dylan W.H. Sung (Phonology & Official Romanization Schemes)

- Discovering dialects

- Hello Mandarin: Introduction of Mandarin / Putonghua

- CEDICT Chinese English Dictionary

- Editorial on use of dialects from China Daily. Raymond Zhou. 19 November 2005

- Chinese Example Sentences

- Mandarin Chinese

- 中国語方言リンク集 Link to Web pages on Chinese dialects

Chinese language(s) Major

subdivisionsNortheastern · Ji-Lu · Jiao-Liao · Zhongyuan · Southwestern · Lan-Yin · Lower Yangtze · Beijing · Dungan · Xuzhou · Luoyang · Jinan · Karamay · Nanking · Sichuanese · Kunming · Shenyang · Harbin · Qingdao · Guanzhong · Dalian · Weihai · Taiwanese Mandarin · Filipino-Mandarin · Malaysian Mandarin · Singaporean Mandarin · Chuan-puYueother MinDisputedUnclassifiedStandardized forms

(Ausbausprache)Phonology History Written Chinese OfficialHistorical scriptsOtherList of varieties of Chinese Categories:- Chinese dialects

- Sinitic

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.