- Omaha, Nebraska

-

Omaha — City — An aerial view of Downtown Omaha from the east

SealNickname(s): Gateway to the West[1] Motto: Fortiter in Re (Latin)

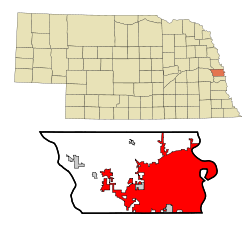

"Courageously in every enterprise"Location in Nebraska and Douglas County. Location in the United States Coordinates: 41°15′N 96°0′W / 41.25°N 96°WCoordinates: 41°15′N 96°0′W / 41.25°N 96°W Country United States State Nebraska County Douglas Founded 1854 Incorporated 1857 Government – Mayor Jim Suttle (D) – City Clerk Buster Brown – City Council Members listArea – City 118.9 sq mi (307.9 km2) – Land 115.7 sq mi (299.7 km2) – Water 3.2 sq mi (8.2 km2) Elevation 1,090 ft (332 m) Population (2010)[2] – City 408,958 – Density 3,370.7/sq mi (1,301.4/km2) – Metro 885,350 Time zone CST (UTC-6) – Summer (DST) CDT (UTC-5) ZIP codes 68022, 68101-68164 Area code(s) 402, 531 FIPS code 31-37000[3] GNIS feature ID 0835483[4] Website www.cityofomaha.org Omaha (pronounced /ˈoʊməhɑː/) is the largest city in the state of Nebraska, United States, and is the county seat of Douglas County.[5] It is located in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about 20 miles (30 km) north of the mouth of the Platte River. Omaha is the anchor of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area, which includes Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha.

According to the 2010 Census, Omaha's population was 408,958, making it the nation's 42nd-largest city. Including its suburbs, Omaha formed the 60th-largest metropolitan area in the United States in 2010, with an estimated population of 865,350 residing in eight counties. There are more than 1.2 million residents within a 50-mile (80-km) radius of the city's center, forming the Greater Omaha area.

Omaha's pioneer period began in 1854 when the city was founded by speculators from neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa. The city was founded along the Missouri River, and a crossing called Lone Tree Ferry earned the city its nickname, the "Gateway to the West." During the 19th century, Omaha's central location in the United States caused the city to become an important national transportation hub. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the transportation and jobbing sectors were important in the city, along with its railroads and breweries. In the 20th century, the Omaha Stockyards, once the world's largest, and its meatpacking plants, gained international prominence.

Today, Omaha is the home to six Fortune 500 companies: Kellogg Company, ConAgra Foods, Union Pacific Corporation, Mutual of Omaha, Peter Kiewit and Sons, Inc., and Berkshire Hathaway.[6] Berkshire Hathaway is headed by local investor Warren Buffett, who was the richest person in the world for the first half of 2008.[7] Omaha is also the home to four Fortune 1000 headquarters, TD Ameritrade, West Corporation, Valmont Industries, and Werner Enterprises. First National Bank of Omaha is the largest privately held bank in the United States. Headquarters for Leo A Daly, HDR, Inc. and DLR Group, three of the US's top 30 architectural and engineering firms, are located in Omaha.

The modern economy of Omaha is diverse and built on skilled knowledge jobs. In 2009, Forbes identified Omaha as the nation's number one "Best Bang-For-The Buck City" and number one on "America's Fastest-Recovering Cities" list. Tourism in Omaha benefits the city's economy greatly, with the annual College World Series providing important revenue and the city's Henry Doorly Zoo serving as the top attraction in Nebraska. Omaha hosted the Olympic swim trials in 2008, and is scheduled to do so again in 2012.

A historic preservation movement in Omaha has led to a number of historic structures and districts being designated Omaha Landmarks or listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Since its founding, ethnic groups in the city have clustered in enclaves in north, south and downtown Omaha. In its early days, the city's history included a variety of crime such as illicit gambling and riots. Today, the diverse culture of Omaha includes a variety of performance venues, museums, and musical heritage, including the historically-significant jazz scene in North Omaha and the modern and influential "Omaha Sound". Sports have been important in Omaha for more than a century, and the city currently hosts three professional sports teams. Omaha also has a number of recreational trails and parks located throughout the city.

Contents

History

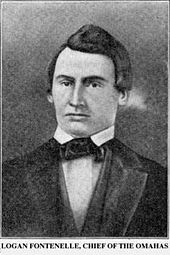

Logan Fontenelle, chief of the Omaha Tribe that ceded land to the U.S. government which became the city of Omaha

Logan Fontenelle, chief of the Omaha Tribe that ceded land to the U.S. government which became the city of Omaha

Various Native American tribes had lived in the land that became Omaha, including since the 17th century, the Omaha and Ponca, Dhegian-Siouan-language people who had originated in the lower Ohio River valley and migrated west by the early 17th century; Pawnee, Otoe, Missouri, and Ioway. The word Omaha (actually UmoNhoN or UmaNhaN) means "Dwellers on the bluff".[8]

In 1804 the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed by the riverbanks where the city of Omaha would be built. Between July 30 and August 3, 1804, members of the expedition, including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, met with Oto and Missouria tribal leaders at the Council Bluff at a point about 20 miles (30 km) north of present-day Omaha.[9] Immediately south of that area, Americans built several fur trading outposts in succeeding years, including Fort Lisa in 1812;[10] Fort Atkinson in 1819;[11] Cabanné's Trading Post, built in 1822, and Fontenelle's Post in 1823, in what became Bellevue.[12] There was fierce competition among fur traders until John Jacob Astor created the monopoly of the American Fur Company. The Mormons built a town called Cutler's Park in the area in 1846.[13] While it was temporary, the settlement provided the basis for further development in the future.[14]

Through 26 separate treaties with the United States federal government, Native American tribes in Nebraska gradually ceded the lands currently comprising the state. The treaty and cession involving the Omaha area occurred in 1854 when the Omaha Tribe ceded most of east-central Nebraska.[15] Logan Fontenelle, chief of the Omaha, played an essential role in those proceedings.

Pioneer Omaha

Before it was legal to claim land in Indian Country, William D. Brown was operating the Lone Tree Ferry to bring settlers from Council Bluffs, Iowa to the area that became Omaha. Brown is generally credited as having the first vision for a city where Omaha now sits.[16] The passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854 was presaged by the staking out of claims around the area to become Omaha by residents from neighboring Council Bluffs. On July 4, 1854, the city was informally established at a picnic on Capital Hill, current site of Omaha Central High School.[17] Soon after, the Omaha Claim Club was formed to provide vigilante justice for claim jumpers and others who infringed on the land of many of the city's founding fathers.[18] Some of this land, which now wraps around Downtown Omaha, was later used to entice Nebraska Territorial legislators to an area called Scriptown.[19] The Territorial capitol was located in Omaha, but when Nebraska became a state in 1867, the capital was relocated to Lincoln, 53 miles (85 km) south-west of Omaha.[20] The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled against numerous landowners whose violent actions were condemned in Baker v. Morton.[21]

Many of Omaha's founding figures stayed at the Douglas House or the Cozzens House Hotel.[22] Dodge Street was important early in the city's early commercial history; North 24th Street and South 24th Street developed independently as business districts, as well. Early pioneers were buried in Prospect Hill Cemetery and Cedar Hill Cemetery.[23] Cedar Hill closed in the 1860s and its graves were moved to Prospect Hill, where pioneers were later joined by soldiers from Fort Omaha, African Americans and early European immigrants.[24] There are several other historical cemeteries in Omaha, historical Jewish synagogues and historical Christian churches dating from the pioneer era, as well.

19th century

The economy of Omaha boomed and busted through its early years. Omaha was a stopping point for settlers and prospectors heading west, either overland or via the Missouri River. The Steamboat Bertrand sank north of Omaha on its way to the goldfields in 1865. Its massive collection of artifacts is on display at the nearby Desoto National Wildlife Refuge. The jobbing and wholesaling district brought new jobs, followed by the railroads and the stockyards.[25] Groundbreaking for the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1863, provided an essential developmental boom for the city.[26] The Union Pacific Railroad was authorized by the U.S. Congress to begin building westward railways in 1862;[27][28] in January 1866 it commenced construction out of Omaha.[29]

Equally as important, the Union Stockyards were founded in 1883.[30] Within twenty years of the founding of the Union Stockyards in South Omaha, four of the five major meatpacking companies in the United States were located in Omaha. By the 1950s, half the city's workforce was employed in meatpacking and processing. Meatpacking, jobbing and railroads were responsible for most of the growth in the city from the late 19th century through the early decades of the 20th century.[31]

Immigrants soon created ethnic enclaves throughout the city, including Irish in Sheelytown in South Omaha; Germans in the Near North Side, joined by Eastern European Jews and black migrants from the South; Little Italy and Little Bohemia in South Omaha.[32] Beginning in the late 19th century, Omaha's upper class lived in posh enclaves throughout the city, including the south and north Gold Coast neighborhoods, Bemis Park, Kountze Place, Field Club and throughout Midtown Omaha. They traveled the city's sprawling park system on boulevards designed by renowned landscape architect Horace Cleveland.[33] The Omaha Horse Railway first carried passengers throughout the city, as did the later Omaha Cable Tramway Company and several similar companies. In 1888, the Omaha and Council Bluffs Railway and Bridge Company built the Douglas Street Bridge, the first pedestrian and wagon bridge between Omaha and Council Bluffs.[34] Gambling, drinking and prostitution were widespread in the 19th century, first rampant in the city's Burnt District and later in the Sporting District.[35] Controlled by Omaha's political boss Tom Dennison by 1890, criminal elements enjoyed support from Omaha's "perpetual" mayor, "Cowboy Jim" Dahlman, nicknamed for his eight terms as mayor.[36][37] Calamities such as the Great Flood of 1881 did not slow down the city's violence.[38] In 1882, the Camp Dump Strike pitted state militia against unionized strikers, drawing national attention to Omaha's labor troubles. The Governor of Nebraska had to call in U.S. Army troops from nearby Fort Omaha to protect strikebreakers for the Burlington Railroad, bringing along Gatling guns and a cannon for defense. When the event ended, there was one man dead and several wounded.[39] In 1891, a mob hanged Joe Coe, an African-American porter after he was accused of raping a white girl.[40] There were several other riots and civil unrest events in Omaha during this period, as well.

In 1898, Omaha's leaders, under the guidance of Gurdon Wattles, held the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, touted as a celebration of agricultural and industrial growth throughout the Midwest.[41] The Indian Congress, which drew more than 500 American Indians from across the country, was held simultaneously. More than 2 million visitors attended these events, located at Kountze Park and the Omaha Driving Park in the Kountze Place neighborhood.[42]

20th century

With dramatically increasing population in the 20th century, there was major civil unrest in Omaha, resulting from competition and fierce labor struggles.[43] In 1900, Omaha was the center of a national uproar over the kidnapping of Edward Cudahy, Jr., the son of a local meatpacking magnate.[44] The city's labor and management clashed in bitter strikes, racial tension escalated as blacks were hired as strikebreakers, and ethnic strife broke out.[45] A major riot by ethnic whites in South Omaha destroyed the city's Greek Town in 1909, completely driving out the Greek population.[46] The civil rights movement in Omaha has roots that extend back to 1912, when the first chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People west of the Mississippi River was founded in the city.[47] The Omaha Easter Sunday Tornado of 1913 destroyed much of the city's African American community, in addition to much of Midtown Omaha.[48] Six years later in 1919 the city was caught up in the Red Summer riots when thousands of ethnic whites marched from South Omaha to the courthouse to lynch a black worker, Willy Brown, a suspect in an alleged rape of a white woman. The mob burned the Douglas County Courthouse to get the prisoner, causing more than $1,000,000 damage. They hung and shot Will Brown, then burned his body.[49] Troops were called in from Fort Omaha to quell the riot, prevent more crowds gathering in South Omaha, and to protect the black community in North Omaha.[50]

The culture of North Omaha thrived throughout the 1920s through 1950s, with several creative figures, including Tillie Olsen, Wallace Thurman, Lloyd Hunter, and Anna Mae Winburn emerging from the vibrant Near North Side.[51] Musicians created their own world in Omaha, and also joined national bands and groups that toured and appeared in the city.[52]

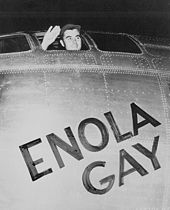

After the tumultuous Great Depression of the 1930s, Omaha rebounded with the development of Offutt Air Force Base just south of the city. The Glenn L. Martin Company operated a factory there in the 1940s that produced 521 B-29 Superfortresses, including the Enola Gay and Bockscar used in the atomic bombing of Japan in World War II.[53] The construction of Interstates 80, 480 and 680, along with the North Omaha Freeway, spurred development. There was also controversy, particularly in North Omaha, where several neighborhoods were bisected by new routes.[54] Creighton University hosted the DePorres Club, an early civil rights group whose sit-in strategies for integration of public facilities predated the national movement, starting in 1947.[55] Following the development of the Glenn L. Martin Company bomber manufacturing plant in Bellevue at the beginning of World War II, the relocation of the Strategic Air Command to the Omaha suburb in 1948 provided a major economic boost to the area.[56]

From the 1950s through the 1960s, more than 40 insurance companies were headquartered in Omaha, including Woodmen of the World and Mutual of Omaha. By the late 1960s, the city rivaled, but never surpassed, the United States insurance centers of Hartford, Connecticut, New York City and Boston, Massachusetts.[57] After surpassing Chicago in meat processing by the late 1950s, Omaha suffered the loss of 10,000 jobs as both the railroad and meatpacking industries restructured. The city struggled for decades to shift its economy as workers suffered. Poverty became more entrenched among families who remained in North Omaha. In the 1960s, three major race riots along North 24th Street destroyed the Near North Side's economic base, with recovery slow for decades.[58] In 1969, Woodmen Tower was completed and became Omaha's tallest building and first major skyscraper at 478 feet (146 m), a sign of renewal.

Since the 1970s, Omaha has continued expanding and growing, mostly to available land to the west. West Omaha has become home to the majority of the city's population. North and South Omaha's populations continue to be centers of new immigrants, with economic and racial diversity.[59] In 1975 a major tornado, along with a major blizzard, caused more than $100 million in damages in 1975 dollars.[60] Downtown Omaha has since been rejuvenated in numerous ways, starting with the development of Gene Leahy Mall[61] and W. Dale Clark Library[62] in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, Omaha's fruit warehouses were converted into a shopping area called the Old Market. The demolition of Jobber's Canyon in 1989 led to the creation of the ConAgra Foods campus.[63] Several nearby buildings, including the Nash Block, have been converted into condominiums. The stockyards were taken down; the only surviving building is the Livestock Exchange Building, which was converted to multi-use and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[64]

21st century

Around the turn of the 21st century, several new downtown skyscrapers and cultural institutions were built.[65] One First National Center was completed in 2002, replacing the Woodmen Tower as the tallest building in Omaha as well as in the state at 638 feet (194 m). The creation of the city's new North Downtown included the construction of the Qwest Center and the Slowdown/Film Streams development at North 14th and Webster Streets.[66] Construction of the new TD Ameritrade Park began in 2009 and was completed in 2011, also in the North Downtown area, near the Qwest Center.

New construction has occurred throughout the city since the turn of the century. Important retail and office developments have occurred in West Omaha such as the Village Pointe shopping center and several business parks including First National Business Park and parks for Bank of the West and C&A Industries, Inc and Morgan Stanley Smith Barney and several others.[67] Downtown and Midtown Omaha have both seen the development of a significant number of condominiums in recent years.[68][69] In Midtown Omaha significant mixed-use projects are underway. The site of the former Ak-Sar-Ben arena is being redeveloped into a mixed use development Aksarben Village. In January 2009 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska announced plans to build a new 10 story, $98 million headquarters, in the Aksarben Village, to be completed in Spring 2011.[70] The other major mixed-use development is Midtown Crossing at Turner Park. Being developed by Mutual of Omaha, the development includes construction of several condominium towers and retail businesses built around Omaha's Turner Park.[71][72]

The Holland Performing Arts Center opened in 2005 near the Gene Leahy Mall and the Union Pacific Center opened in 2004.

There have also been several developments along the Missouri River waterfront in downtown. The Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge was opened to foot and bicycle traffic on September 28, 2008.[73] Started in 2003,[74] RiverFront Place Condos first phase was completed in 2006 and is fully occupied and construction of the second tower began in 2009. The development along Omaha's riverfront is attributed with prompting the City of Council Bluffs to move their own riverfront development time line forward.[75]

In summer 2008 the United States Olympic Team swimming trials were held in Omaha.[76][77] The event was a highlight in the city's sports community,[78] as well as a showcase for redevelopment in the downtown area.

Geography

Omaha is located at 41°15′N 96°0′W / 41.25°N 96°W. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 118.9 square miles (307.9 km²). 115.7 square miles (299.7 km²) of it is land and 3.2 square miles (8.2 km²) of it is water. The total area is 2.67% water. Situated in the Midwestern United States on the shore of the Missouri River in eastern Nebraska, much of Omaha is built in the Missouri River Valley. Other significant bodies of water in the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area include Lake Manawa, Papillion Creek, Carter Lake, Platte River and the Glenn Cunningham Lake. The city's land has been altered considerably with substantial land grading throughout Downtown Omaha and scattered across the city.[79] East Omaha sits on a flood plain west of the Missouri River. The area is the location of Carter Lake, an oxbow lake. The lake was once the site of East Omaha Island and Florence Lake, which dried up in the 1920s.

The Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area consists of eight counties; five in Nebraska and three in Iowa.[80] now includes Harrison, Pottawattamie, and Mills Counties in Iowa and Washington, Douglas, Sarpy, Cass, and Saunders Counties in Nebraska. This area was formerly referred to only as the Omaha Metropolitan Statistical Area and consisted of only five counties: Pottawattamie in Iowa, and Washington, Douglas, Cass, and Sarpy in Nebraska.[81] The Omaha-Council Bluffs combined statistical area comprises the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan statistical area and the Fremont Micropolitan statistical area; the CSA has a population of 858,720 (2005 Census Bureau estimate). Omaha ranks as the 42nd-largest city in the United States, and is the core city of its 60th-largest metropolitan area.[82] There are currently no consolidated city-counties in the area; the City of Omaha studied the possibility extensively through 2003 and concluded, "The City of Omaha and Douglas County should merge into a municipal county, work to commence immediately, and that functional consolidations begin immediately in as many departments as possible, including but not limited to parks, fleet management, facilities management, local planning, purchasing and personnel."[83]

Geographically, Omaha is considered as being located in the "Heartland" of the United States. Important environmental impacts on the natural habitat in the area include the spread of invasive plant species, restoring prairies and bur oak savanna habitats, and managing the whitetail deer population.[84]

Omaha is home to several hospitals, located mostly along Dodge St (US6). Being the county seat, it is also the location of the county courthouse.

Neighborhoods

Omaha is generally divided into five geographic areas: Downtown, Midtown, North Omaha, South Omaha and West Omaha. West Omaha includes the Miracle Hills, Girls and Boys Town, Regency, and Gateway areas.[85] There is also a small community in East Omaha. The city has a wide range of historical and new neighborhoods and suburbs that reflect its socioeconomic diversity.[86] Early neighborhood development happened in ethnic enclaves,[87] including Little Italy, Little Bohemia, Little Mexico and Greek Town.[88] According to U.S. Census data, five European ethnic enclaves existed in Omaha in 1880, expanding to nine in 1900.[89]

At the turn of the 20th century. the City of Omaha annexed several surrounding communities, including Florence, Dundee and Benson. At the same time, the city annexed all of South Omaha, including the Dahlman and Burlington Road neighborhoods. From its first annexation in 1857 (of East Omaha) to its recent and controversial annexation of Elkhorn, Omaha has continually had an eye towards growth.[90]

Starting in the 1950s, development of highways and new housing led to movement of middle class to suburbs in West Omaha. Some of the movement was designated as white flight from racial unrest in the 1960s.[91] Newer and poorer migrants lived in older housing close to downtown; those residents who were more established moved west into newer housing. Some suburbs are gated communities or have become edge cities.[92] Recently, Omahans have made strides to revitalize the downtown and Midtown areas with the redevelopment of the Old Market, Turner Park, Gifford Park, and the designation of the Omaha Rail and Commerce Historic District.

Landmark preservation

Main article: Landmarks in Omaha, NebraskaOmaha is home to dozens of nationally, regionally and locally significant landmarks.[93] The city has more than a dozen historic districts, including Fort Omaha Historic District, Gold Coast Historic District, Omaha Quartermaster Depot Historic District, Field Club Historic District, Bemis Park Historic District, and the South Omaha Main Street Historic District. Omaha is notorious for its 1989 demolition of 24 buildings in the Jobbers Canyon Historic District, which represents to date the largest loss of buildings on the National Register.[94] The only original building surviving of that complex is the Nash Block.

Omaha has almost one hundred individual properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Bank of Florence, Holy Family Church, the Christian Specht Building and the Joslyn Castle. There are also three properties designated as National Historic Landmarks.[95]

Locally designated landmarks, including residential, commercial, religious, educational, agricultural and socially significant locations across the city, honor Omaha's cultural legacy and important history. The City of Omaha Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission is the government body that works with the mayor of Omaha and the Omaha City Council to protect historic places. Important history organizations in the community include the Douglas County Historical Society.[96]

Climate

Omaha, due to its latitude of 41.26˚N and location far from moderating bodies of water or mountain ranges, displays a humid continental climate (Koppen Dfa), with hot summers and cold winters. July averages 76.7 °F (24.8 °C), with moderate, but sometimes high humidity and relatively frequent thunderstorms, usually rather violent and capable of spawning severe weather or tornadoes; the January mean is 21.7 °F (−5.7 °C). The maximum temperature recorded in the city is 114 °F (46 °C), the minimum −32 °F (−36 °C). Average yearly precipitation is 30.2 inches (767 mm), falling mostly in the warmer months. What precipitation does fall in winter usually takes the form of snow, with average yearly snowfall being around 26.8 inches (68 cm).[97][98]

Climate data for Omaha (Eppley Airfield) Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °F (°C) 69

(21)78

(26)91

(33)96

(36)103

(39)107

(42)114

(46)111

(44)104

(40)96

(36)83

(28)72

(22)114

(46)Average high °F (°C) 31.7

(−0.2)37.9

(3.3)50.4

(10.2)63.2

(17.3)73.7

(23.2)83.7

(28.7)87.4

(30.8)85.2

(29.6)77.3

(25.2)65.2

(18.4)47.8

(8.8)34.8

(1.6)61.5 Average low °F (°C) 11.6

(−11.3)18

(−8)28.1

(−2.2)39.6

(4.2)50.7

(10.4)60.6

(15.9)65.9

(18.8)63.8

(17.7)53.5

(11.9)41.1

(5.1)28.1

(−2.2)16.4

(−8.7)39.8 Record low °F (°C) −32

(−36)−26

(−32)−16

(−27)5

(−15)25

(−4)39

(4)44

(7)43

(6)28

(−2)8

(−13)−14

(−26)−25

(−32)−32

(−36)Precipitation inches (mm) 0.77

(19.6)0.80

(20.3)2.13

(54.1)2.94

(74.7)4.44

(112.8)3.95

(100.3)3.86

(98)3.21

(81.5)3.17

(80.5)2.21

(56.1)1.82

(46.2)0.92

(23.4)30.22

(767.6)Snowfall inches (cm) 6.3

(16)5.5

(14)4.5

(11.4)1.3

(3.3)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0.3

(0.8)3.4

(8.6)5.5

(14)26.8

(68.1)Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) 5.9 6.1 8.3 10.4 12.0 10.0 10.1 8.5 8.3 6.6 7.0 6.7 99.9 Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) 4.6 4.2 2.7 1.1 0 0 0 0 0 0.2 2.5 4.8 20.1 Sunshine hours 167.4 158.2 207.7 231.0 275.9 315.0 331.7 297.6 246.0 217.0 147.0 133.3 2,727.8 Source no. 1: [99] Source no. 2: NOAA [100] , HKO [101] Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1860 1,883 — 1870 16,083 754.1% 1880 30,518 89.8% 1890 140,452 360.2% 1900 102,555 −27.0% 1910 124,096 21.0% 1920 191,061 54.0% 1930 214,006 12.0% 1940 223,844 4.6% 1950 251,117 12.2% 1960 301,598 20.1% 1970 346,929 15.0% 1980 313,939 −9.5% 1990 335,795 7.0% 2000 390,007 16.1% 2010 408,958 4.9% source:[102][103] According to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey, the racial composition of Omaha was as follows:

- White: 76.7% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 71.1%)

- Black or African American: 12.8%

- Native American: 0.4%

- Asian: 2.1%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%

- Some other race: 5.1%

- Two or more races: 2.8%

- Hispanic or Latino: 11.4%

Source:[104]

As of the census[3] of 2000, there are 390,007 people, 156,738 households, and 94,983 families residing within city limits. The population density is 3,370.7 people per square mile (1,301.5/km²). There are 165,731 housing units at an average density of 1,432.4 per square mile (553.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city is 78.39% White, 13.31% African American, 0.67% Native American, 1.74% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 3.91% from other races, and 1.92% from two or more races. 7.54% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race.[105]

There are 156,738 households out of which 30.0% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.8% are married couples living together, 13.0% have a female householder with no husband present, and 39.4% are non-families. 31.9% of all households are made up of individuals and 9.4% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.42 and the average family size is 3.10. In the city the average age of the population is diverse with 25.6% under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to 44, 20.7% from 45 to 64, and 11.8% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 34 years. For every 100 females there are 95.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 92.2 males.[106]

The median income for a household in the city is $40,006, and the median income for a family is $50,821. Males have a median income of $34,301 versus $26,652 for females. The per capita income for the city is $21,756. 11.3% of the population and 7.8% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 15.6% of those under the age of 18 and 7.4% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.[107]

People

View of 24th and Lake Streets in North Omaha, site of many notable events in Omaha's African American community

Native Americans were the first residents in the Omaha area. The city of Omaha was established by European Americans from neighboring Council Bluffs who arrived from the Northeast United States a few years earlier. While much of the early population was of Yankee stock, over the next 100 years numerous ethnic groups moved to the city. Irish immigrants in Omaha originally moved to an area in present-day North Omaha called "Gophertown", as they lived in dirt dugouts.[108] That population was followed by Polish immigrants in the Sheelytown neighborhood, and many immigrants were recruited for jobs in South Omaha's stockyards and meatpacking industry.[109] The German community in Omaha was largely responsible for founding its once-thriving beer industry,[110] including the Metz, Krug, Falstaff and the Storz breweries.

In the early 20th century, Jewish immigrants set up numerous businesses along the North 24th Street commercial area. It suffered with the loss of industrial jobs in the 1960s and later, and the shifting of population west of the city. The commercial area is now the center of the African American community, concentrated in North Omaha.[111] The African-American community has maintained its social and religious base, while it is currently experiencing an economic revitalization.

Omaha's first Italian enclave grew south of downtown, with many Italian immigrants coming to the city to work in the Union Pacific shops.[112] Scandinavians first came to Omaha as Mormon settlers in the Florence neighborhood.[113][114] Czechs had a strong political and cultural voice in Omaha,[115] and were involved in a variety of trades and businesses, including banks, wholesale houses, and funeral homes. The Notre Dame Academy and Convent and Czechoslovak Museum are legacies of their residence.[116] Today the legacy of the city's early European immigrant populations is evident in many social and cultural institutions in Downtown and South Omaha.

Mexicans originally immigrated to Omaha to work in the rail yards. Today they compose the majority of South Omaha's Hispanic population and many have taken jobs in meat processing.[117] Other significant early ethnic populations in Omaha included Danes, Poles, and Swedes.

A growing number of African immigrants have made their homes in Omaha in the last twenty years. There are approximately 8,500 Sudanese living in Omaha, comprising the largest population of Sudanese refugees in the United States. Most have immigrated since 1995 because of warfare in their nation. Ten different tribes are represented, including the Nuer, Dinka, Equatorians, Maubans and Nubians. Most Sudanese people in Omaha speak the Nuer language.[118] Other Africans have immigrated to Omaha as well, with one-third from Nigeria, and significant populations from Kenya, Togo, Cameroon and Ghana.[119][120][121]

Race relations

Part of a series onAfrican Americans Czechs Danes Germans Greeks Irish Italians Jews Mexicans Poles Swedes Racial tension Timeline of racial tension Civil rights movement With the expansion of railroad and industrial jobs in meatpacking, Omaha attracted many new immigrants and migrants. As the major city in Nebraska, it has historically been more racially and ethnically diverse than the rest of the state.[122] At times rapid population change, overcrowded housing and job competition have aroused racial and ethnic tensions. Around the turn of the 20th century, violence towards new immigrants in Omaha often erupted out of suspicions and fears.[123]

The Greek Town Riot in 1909 flared after increased Greek immigration, Greeks' working as strikebreakers, and the killing of an Irish policeman provoked violence among earlier immigrants such as ethnic Irish.[124] That mob violence forced the Greek immigrant population to flee from the city.[125][126] By 1910, 53.7% of Omaha’s residents and 64.2% of South Omaha’s residents were foreign born or had at least one parent born outside of America.[127] Six years after the Greek Town Riot, in 1915, a Mexican immigrant named Juan Gonzalez was killed by a mob near Scribner, a town in the Greater Omaha metropolitan area. The event occurred after an Omaha Police Department officer was investigating a criminal operation selling goods stolen from the nearby railroad yards. Racial profiling targeted Gonzalez as the culprit. After escaping the city, he was trapped along the Elkhorn River, where the mob, including several policemen from Omaha, shot him more than twenty times. Afterward it was discovered that Gonzalez was unarmed, and that he had a reliable alibi for the time of the murder. Nobody was ever indicted for his lynching.[128] In the fall of 1919, following Red Summer, postwar social and economic tensions, the earlier hiring of blacks as strikebreakers, and job uncertainty contributed to a mob from South Omaha lynching Willy Brown and the ensuing Omaha Race Riot. Trying to defend Brown, the city's mayor, Edward Parsons Smith, was lynched also, surviving only after a quick rescue.[129]

Similar to other industrial cities in the U.S., Omaha suffered severe job losses in the 1950s, more than 10,000 in total, as both the railroad and meatpacking industries restructured. Stockyards and packing plants were located closer to ranches, and union achievements were lost as wages declined in surviving jobs.[130] Many workers left the area if they could get to other jobs. Poverty deepened in areas of the city whose residents had depended on those jobs, specifically North and South Omaha. At the same time, with reduced revenues, the city had less financial ability to respond to longstanding problems. Despair after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968 contributed to riots in North Omaha, including one at the Logan Fontenelle Housing Project.[131] For some, the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha, Nebraska evolved towards black nationalism, as the Black Panther Party was involved in tensions in the late 1960s. Organizations such as the Black Association for Nationalism Through Unity became popular among the city's African-American youth. This tension culminated in the cause célèbre trial of the Rice/Poindexter Case, in which an Omaha Police Department officer was killed by a bomb while answering an emergency call. After 5 years of obscurity, the black population was finally able to vote.

Whites in Omaha have followed the white flight pattern, suburbanizing to West Omaha over time.[132] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, gang violence and incidents between the Omaha Police Department and members of the African-American community aggravated relations between groups in North and South Omaha. More recent Hispanic immigrants, concentrated in South Omaha, have struggled to earn living wages in meatpacking, adapt to a new society, and deal with discrimination.[133]

Economy

According to USA Today, Omaha ranks eighth among the nation's 50 largest cities in both per-capita billionaires and Fortune 500 companies.[134] Major employers in the area include Alegent Health System, Omaha Public Schools, First Data Corporation, Methodist Health System, Mutual of Omaha, ConAgra Foods, Nebraska Medical Center, Offutt Air Force Base, and the West Corporation.[135] With diversification in several industries, including banking, insurance, telecommunications, architecture/construction, and transportation, Omaha's economy has grown dramatically since the early 1990s. In 2001 Newsweek identified Omaha as one of the Top 10 high-tech havens in the nation.[136] Six national fiber optic networks converge in Omaha.[137]

Omaha's most prominent businessman is Warren Buffett, nicknamed the "Oracle of Omaha", who is regularly ranked one of the richest people in the world. Five Omaha-based companies: Berkshire Hathaway, ConAgra Foods, Union Pacific Railroad, Mutual of Omaha, and Kiewit Corporation, are among the Fortune 500.[138]

Omaha is the headquarters of several other major corporations, including the Gallup Organization, TD Ameritrade, infoGROUP, Werner Enterprises, First National Bank and First Comp Insurance. Many large technology firms have major operations or operational headquarters in Omaha, including Bank of the West, First Data, PayPal and LinkedIn. The city is also home to three of the 30 largest architecture firms in the United States, including HDR, Inc., DLR Group, Inc., and Leo A Daly.[139] Despite this progress, as of October 2007, the city of Omaha, the 42nd largest in the country, has the fifth highest percentage of low-income African Americans in the country.[140]

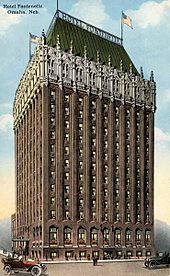

Tourist attractions in Omaha include history, sports, outdoors and cultural experiences. Its principal tourist attractions are the Henry Doorly Zoo and the College World Series.[141] The Old Market in Downtown Omaha is another major attraction and is important to the city's retail economy. The city has been a tourist destination for many years. Famous early visitors included British author Rudyard Kipling and General George Crook. In 1883 Omaha hosted the first official performance of the Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show for eight thousand attendees.[142] In 1898 the city hosted more than 1,000,000 visitors from across the United States at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, a world's fair that lasted for more than half the year.[143]

Research on leisure and hospitality situates Omaha in the same tier for tourists as the neighboring cities of Topeka, Kansas, Kansas City, Missouri, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and Denver, Colorado.[144] A recent study found that investment of $1 million in cultural tourism generated approximately $83,000 in state and local taxes, and provided support for hundreds of jobs for the metropolitan area, which in turn led to additional tax revenue for government.[141][145]

Culture

Main article: Culture in OmahaMain article: Culture in North Omaha, NebraskaThe city's historical and cultural attractions have been lauded by numerous national newspapers, including the Boston Globe[146] and The New York Times.[147] Omaha is home to the Omaha Community Playhouse, the largest community theater in the United States.[148][149] The Omaha Symphony Orchestra and its modern Holland Performing Arts Center,[150] the Opera Omaha at the Orpheum theater, the Blue Barn Theatre, and The Rose Theater form the backbone of Omaha's performing arts community. Opened in 1931, the Joslyn Art Museum has significant art collections.[151] Since its inception in 1976, Omaha Children's Museum has been a place where children can challenge themselves, discover how the world works and learn through play. The Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, one of the nation's premier urban artist colonies, was founded in Omaha in 1981,[152] and the Durham Museum is accredited with the Smithsonian Institution for traveling exhibits.[153] The city is also home to the largest singly funded mural in the nation, "Fertile Ground", by Meg Saligman.[154] The annual Omaha Blues, Jazz, & Gospel Festival celebrates local music along with the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame.

In 1955 Omaha's Union Stockyards overtook Chicago's stockyards as the United States' meat packing center. This legacy is reflected in the cuisine of Omaha, with renowned steakhouses such as Gorat's and the recently closed Mister C's, as well as the retail chain Omaha Steaks.

Henry Doorly Zoo

The Henry Doorly Zoo is widely considered one of the premier zoos in the world.[155][156][157] The zoo is home to the world's largest nocturnal exhibit and indoor swamp;[158] the world's largest indoor rainforest, the world's largest indoor desert,[159] and the largest geodesic dome in the world (13 stories tall).[160][161] The Zoo is Nebraska’s number one paid attendance attraction and has welcomed more than 25 million visitors over the past 40 years.[162]

Old Market

The Old Market is a major historic district in Downtown Omaha listed on the National Register of Historical Places Today, its warehouses and other buildings house shops, restaurants, bars, and art galleries.[163] Downtown is also the location of the Omaha Rail and Commerce Historic District, which has several art galleries and restaurants as well. The Omaha Botanical Gardens features 100 acres (40 ha) with a variety of landscaping, and the new Kenefick Park recognizes Union Pacific Railroad's long history in Omaha.[164] North Omaha has several historical cultural attractions including the Dreamland Historical Project, Love’s Jazz and Art Center, and the John Beasley Theater.[165] The annual River City Roundup is celebrated at Fort Omaha, and the neighborhood of Florence celebrates its history during "Florence Days". Native Omaha Days is a biennial event celebrating Near North Side heritage.[166]

Religious institutions reflect the city's heritage.[167] The city's Christian community has several historical churches dating from the founding of the city. There are also all sizes of congregations, including small, medium and megachurches. Omaha hosts the only Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints temple in Nebraska, along with a significant Jewish community. There are 152 parishes in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Omaha, and several Orthodox Christian congregations throughout the city.[168]

Music

Omaha's rich history in rhythm and blues, and jazz gave rise to a number of influential bands, including Anna Mae Winburn's Cotton Club Boys and Lloyd Hunter's Seranaders. Rock and roll pioneer Wynonie Harris; jazz great Preston Love; drummer Buddy Miles; and Luigi Waites are among the city's homegrown talent. Doug Ingle from the late 1960s band Iron Butterfly was born in Omaha as was indie-folk singer/songwriter Elliott Smith, though both were raised elsewhere.

Contemporary music groups either located in or originally from Omaha include Mannheim Steamroller, Bright Eyes, The Faint, Cursive, Azure Ray, Tilly and the Wall and 311. During the late 1990s, Omaha became nationally known as the birthplace of Saddle Creek Records, and the subsequent "Omaha Sound" was born from their bands' collective style.[169][170]

Omaha also has a fledgling hip hop scene. Long-time bastion Houston Alexander, a one-time graffiti artist and professional Mixed Martial Arts competitor, is currently a local hip-hop radio show host.[171][172] Cerone Thompson, known as "Scrybe," has had a number one single on college radio stations across the United States. He has also had several number one hits on the local hip hop station respectively titled, "Lose Control" and "Do What U Do". .[173] More recently, in 2009 Eric Scheid, also known as "Titus," released a single called "What Do You Believe" featuring Bizzy Bone from the nationally-known hip hop group Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. The single was produced by Omaha producer J Keez. The record was released by Smashmode Publishing and Timeless Keys Music Publishing which are two Omaha-based music publishing companies. South Omaha's OTR Familia, consisting of MOC and Xpreshin aka XP, have worked with Fat Joes Terror Squad on several songs and have participated in summer concerts with Pitbull, Nicky Jam, and Aventura.[173]

A long heritage of ethnic and cultural bands have come from Omaha. The Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame celebrates the city's long history of African-American music and the Strathdon Caledonia Pipe Band carries on a Scottish legacy. Internationally renowned composer Antonín Dvořák wrote his Ninth ("New World") Symphony in 1893 based on his impressions of the region after visiting Omaha's robust Czech community.[174] In the period surrounding World War I Valentin J. Peter encouraged Germans in Omaha to celebrate their rich musical heritage, too. Frederick Metz, Gottlieb Storz and Frederick Krug were influential brewers whose beer gardens kept many German bands active.

Media and popular culture

The major daily newspaper in Nebraska is the Omaha World-Herald, which is the largest employee-owned newspaper in the United States.[175] Weeklies in the city include the Midlands Business Journal (weekly business publication), American Classifieds (Formerly Thrifty Nickel), a weekly classified newspaper, The Reader (newspaper), and Omaha Magazine, as well as The Omaha Star. Founded in 1938 in North Omaha, the Star is Nebraska's only African-American newspaper.[176] The city is the focus of the Omaha designated market area, and is the 76th largest in the United States.[177] Omaha's four television news stations were found not to represent the city's racial composition in a 2007 study.[178] Cox Communications provides cable television services throughout the metropolitan area.[179]

In 1939, the world premiere of the film Union Pacific was held in Omaha, Nebraska and the accompanying three-day celebration drew 250,000 people. A special train from Hollywood carried director Cecil B. DeMille and stars Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea.[180] Omaha's Boys Town was made famous by the Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney movie Boys Town. Omaha has been featured in recent years by a handful of relatively big budget motion pictures. The city's most extensive exposure can be accredited to Omaha native Alexander Payne, the Oscar-nominated director who shot parts of About Schmidt, Citizen Ruth and Election in the city and suburbs of Papillion and LaVista.

Built in 1962, Omaha's Cinerama was called Indian Hills Theater. Its demolition in 2001 by the Nebraska Methodist Health System was unpopular, with objections from local historical and cultural groups and luminaries from around the world.[181] The Dundee Theatre is the lone surviving single-screen movie theater in Omaha and still shows films.[182] A recent development to the Omaha film scene was the addition of Film Streams's Ruth Sokolof Theater in North Downtown. The two-screen theater is part of the Slowdown facility. It features new American independents, foreign films, documentaries, classics, themed series, and director retrospectives. There are many new theaters opening in Omaha. In addition to the five Douglas Theatres venues in Omaha, two more are opening, including Midtown Crossing Theatres, located on 32nd and Farnam Streets by the Mutual of Omaha Building. Westroads Mall has opened a new multiplex movie theater with 14 screens, operated by Rave Motion Pictures.[183]

Songs about Omaha include "Omaha", by the indie rock band Tapes 'n Tapes;, "Omaha Stylee" by 311; and "Omaha", a song by Moby Grape from their 1967 album Moby Grape, "Omaha" by Counting Crows, "Omaha Celebration" by Pat Metheny, "Omaha" sung by Waylon Jennings and "(Ready Or Not) Omaha Nebraska" by Bowling For Soup.

The 1935 winner of the Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing was named Omaha, and after traveling the world the horse eventually retired to a farm south of the city. The horse made promotional appearances at Ak-Sar-Ben during the 1950s and following his death in 1959 was buried at the racetrack's Circle of Champions.

Sports and recreation

Sports have a long history in Omaha. The Omaha Sports Commission is a quasi-governmental nonprofit organization that coordinates much of the professional and amateur athletic activity in the city, including the 2008 US Olympic Swimming Team Trials and the building of a new stadium in North Downtown.[184][185][186] The University of Nebraska and the Commission co-hosted the 2008 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division One Women's Volleyball Championship in December of that year.[187] Another quasi-governmental board, the Metropolitan Entertainment and Convention Authority, was created by city voters in 2000,[188] and is responsible for maintaining the Qwest Center Omaha.[189] In June 2009, MECA announced that the US Olympic Swim Trials will return to Omaha, to run from June 25 through July 2, 2012. The Swim Trials will overlap with the College World Series, also to be held downtown, for 1–2 days.[190]

Omaha's Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium was home to the Omaha Storm Chasers (most recently known as the Omaha Royals) minor-league baseball team (the AAA affiliate of the Kansas City Royals). Since 1950, it has hosted the annual NCAA College World Series, or CWS, men's baseball tournament in mid-June.[191]

After Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium closed, their tenants moved to new venues. On April 16, 2011 the Omaha Storm Chasers played their first game at the newly built Werner Park in the city of Papillion, just south of Omaha.[192] The CWS moved to the new downtown stadium TD Ameritrade Park in 2011.[193][194] Omaha is also home to the Omaha Diamond Spirit, a collegiate summer baseball team that plays in the MINK league.

In July 2010 Omaha hosted the inaugural TD Ameritrade College Home Run Derby at Rosenblatt Stadium. East Tennessee State University First Baseman Paul Hoilman hit 12 home runs in the final round to beat out Fresno State’s Jordan Ribera and Georgia Tech’s Matt Skole for the title.[195]

The World-Herald will partner with the TD Ameritrade College Home Run Derby Contest on July 2, 2011 for its 27th annual fireworks display. The event will be held at TD Ameritrade Park Omaha.[196]

On April 15, 2010, it was announced that Omaha would be home to a new expansion team in the United Football League to begin play in 2010. The team played its inaugural season at Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium before moving to TD Ameritrade Park for 2011 and beyond.[197]

Named in tribute to Omaha's meatpacking past, the Omaha Beef indoor football team plays at the Omaha Civic Auditorium.

The Creighton University Bluejays compete in a number of NCAA Division I sports. Baseball is played at TD Ameritrade Park Omaha, soccer is played at Morrison Stadium, and basketball is played at the 18,000 seat Qwest Center. The Jays annually rank in the top 15 in attendance each year, averaging more than 16,000 people per game.

Ice hockey is a popular spectator sport in Omaha. The two Omaha-area teams are the Omaha Lancers, a United States Hockey League team that played at Aksarben until 2004, moved to neighboring city of Council Bluffs at the Mid-America Center, and moved back to Omaha in 2009 to play at the Civic Auditorium[198] and the University of Nebraska at Omaha Mavericks, an NCAA Division I team that plays at the Qwest Center. Omaha has a thriving running community and many miles of paved running and biking trails throughout the city and surrounding communities. The Omaha Marathon involves a half-marathon and a 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) race that take place annually in September.[199]

Omaha is the birthplace of numerous important historical and modern sports figures, including 1960 Summer Olympics gold medalist and NBA star Bob Boozer; Baseball Hall of Famer Bob Gibson; 1989 American League Rookie of the Year Gregg Olson; NFL running back Ahman Green; Heisman Trophy winners Johnny Rodgers and Eric Crouch; Pro Football Hall of Famer Gale Sayers; and champion tennis player Andy Roddick.[200]

The City of Omaha administers a parks and recreation department that oversees six regional parks, including Dodge Park and Gene Leahy Mall, and 13 community parks, including Benson Park, Miller Park and Hanscom Park.[201] Part of Omaha's riverfront area is now the Heartland of America Park, including a marina, Miller's Landing, and the Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge, a footbridge crossing into Council Bluffs.[202]

The city's historic boulevards were originally designed by Horace Cleveland in 1889 to work with the parks to create a seamless flow of trees, grass and flowers throughout the city. Florence Boulevard and Fontenelle Boulevard are among the remnants of this system.[203] Omaha boasts more than 80 miles (129 km) of trails for pedestrians, bicyclists and hikers.[204] They include the American Discovery Trail, which traverses the entire United States, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail passes through Omaha as it travels 3,700 miles (5,950 km) westward from Illinois to Oregon. Trails throughout the area are included in comprehensive plans for the city of Omaha, the Omaha metropolitan area, Douglas County, and long-distance coordinated plans between the municipalities of southeast Nebraska.[205]

Professional sports in Omaha Club Sport League Venue Championships Omaha Storm Chasers Baseball Pacific Coast League Rosenblatt Stadium (2010), Werner Park (2011+) 1969, 1970, 1978, 1990 Omaha Nighthawks American football United Football League Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium (2010)

TD Ameritrade ParkOmaha Beef Indoor football Indoor Football League Omaha Civic Auditorium Omaha Lancers Ice hockey United States Hockey League Omaha Civic Auditorium Omaha Rollergirls Roller derby Omaha Rollergirls Mid America Center Omaha Vipers Indoor Soccer Major Indoor Soccer League Omaha Civic Auditorium Education

Education in Omaha is provided by many private and public institutions. Omaha Public Schools is the largest public school district in Nebraska, with more than 47,750 students in more than 75 schools.[206] After a contentious period of uncertainty, in 2007 the Nebraska Legislature approved a plan to create a learning community for Omaha-area school districts with a central administrative board.[207] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Omaha maintains numerous private Catholic schools with 21,500 students in 32 elementary schools and nine high schools.[208] St. Cecilia Grade School at 3869 Webster St. in Midtown Omaha and St. Stephen the Martyr School at 168th and Q street in western Omaha earned national distinction when they received the U.S. Department of Education Blue Ribbon School award.

There are eleven colleges and universities among Omaha's higher education institutions, including the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Omaha's Creighton University is ranked the top non-doctoral regional university in the Midwestern United States by U.S. News and World Report.[209] Creighton maintains a 132-acre (0.5 km2) campus just outside of Downtown Omaha in the new North Downtown district, and the Jesuit-run institution has an enrollment of around 6,700 in its undergraduate, graduate, medical, and law schools. There are more than 10 other colleges and universities in Omaha in the Omaha metro area.

Government and politics

Omaha has a strong mayor form of government, along with a city council that is elected from seven districts across the city. The current mayor is Jim Suttle, who was elected in May 2009. The longest serving mayor in Omaha's history was "Cowboy" Jim Dahlman, who served 20 years over eight terms. He was regarded as the "wettest mayor in America" because of the flourishing number of bars in Omaha during his tenure.[210] Dahlman was a close associate of political boss Tom Dennison.[211] During Dahlman's tenure, the city switched from its original strong-mayor form of government to a city commission government.[212] In 1956, the city switched back.[213]

The elected city clerk is Buster Brown. The City of Omaha administers twelve departments, including finance, police, human rights, libraries and planning.[214] The Omaha City Council is the legislative branch and is made up seven members elected from districts across the city. The council enacts local ordinances and approves the city budget. Government priorities and activities are established in a budget ordinance approved annually. The council takes official action through the passage of ordinances and resolutions. Nebraska’s constitution grants the option of home rule to cities with more than 5,000 residents, meaning they may operate under their own charters. Omaha is one of only three cities in Nebraska to use this option, out of 17 eligible.[215] The City of Omaha is currently considering consolidating with Douglas County government.[216]

Although registered Republicans outnumbered Democrats in the 2nd congressional district, which includes Omaha, Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama opened three campaign offices in the city with 15 staff members to cover the state in fall 2008.[217] Mike Fahey, the former Democratic mayor of Omaha, said he would do whatever it took to deliver the district's electoral vote to Obama; and the Obama campaign considered the district "in play".[218] Former Nebraska U.S. Senator Bob Kerrey and current Senator Ben Nelson campaigned in the city for Obama,[219] and in November 2008 Obama won the district's electoral vote. This was an exceptional win, because with Nebraska's split electoral vote system Obama became the first Democratic presidential candidate to win in Nebraska since 1964.[220]

Crime

Main article: Crime in Omaha, NebraskaFurther information: Gambling in Omaha, NebraskaOmaha's rate of violent crimes per 100,000 residents has been lower than the average rates of three dozen United States cities of similar size. Unlike in Omaha, violent crime overall for those cities has trended upward since 2003. Rates for property crime have decreased for both Omaha and its peer cities during the same time period.[221] In 2006, Omaha was ranked for homicides as 46th out of the 72 cities in the United States of more than 250,000 in population.[222]

As a major industrial city into the mid-20th century, Omaha shared in social tensions of larger cities that accompanied rapid growth and many new immigrants and migrants. By the 1950s, Omaha was a center for illegal gambling,[223] while experiencing dramatic job losses and unemployment because of dramatic restructuring of the railroads and the meatpacking industry, as well as other sectors. Persistent poverty resulting from racial discrimination and job losses generated different crimes in the late 20th century, with drug trade and drug abuse becoming associated with violent crime rates, which climbed after 1986 as Los Angeles gangs made affiliates in the city.[224] Gambling in Omaha has been significant throughout the city's history. From its founding in the 1850s through the 1930s, the city was known as a "wide-open" town, meaning that gambling of all sorts was accepted either openly or in closed quarters. By the mid-20th century, Omaha reportedly had more illicit gambling per capita than any other city in the nation. From the 1930s through the 1970s the city's gambling was controlled by an Italian criminal element.[225] Today, gambling in Omaha is limited to keno, lotteries, and parimutuel betting, leaving Omahans to drive across the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where casinos are legal and there are numerous businesses operating currently. Recently a controversial proposal by the Ponca tribe of Nebraska was approved by the National Indian Gaming Commission. It will allow the tribe to build a casino in Carter Lake, Iowa, which sits geographically on the west side of the Missouri River, adjacent to Omaha, where casinos are illegal.[226][227][228]

Infrastructure

Further information: List of tallest buildings in Omaha, NebraskaIn 2008 Kiplinger's Personal Finance magazine ranked Omaha the No. 3 best city in the United States to "live, work and play."[229] Omaha's growth has required the constant development of new urban infrastructure that influence, allow and encourage the constant expansion of the city.

Retail natural gas and water public utilities in Omaha are provided by the Metropolitan Utilities District.[230] Nebraska is the only public power state in the nation. All electric utilities are non-profit and customer-owned. Electricity in the city is provided by the Omaha Public Power District.[231] Public housing is governed by the Omaha Housing Authority, and public transportation is provided by Metro Area Transit. Qwest and Cox provide local telephone services. The City of Omaha maintains two modern sewage treatment plants.[232]

Portions of the Enron corporation began as Northern Natural Gas Company in Omaha. Northern currently provides three natural gas lines to Omaha. Enron formerly owned UtiliCorp United, Inc., which became Aquila, Inc.. Peoples Natural Gas, a division of Aquila, Inc., currently serves several surrounding communities around the Omaha metropolitan area, including Plattsmouth.[233]

There are several hospitals in Omaha. Research hospitals include the Boys Town National Research Hospital, the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Creighton University Medical Center. The Boys Town facility is well-known for world-class researchers in hearing-related research and high quality treatment. The University of Nebraska Medical Center hosts the Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases, a world-renowned cancer treatment facility named in honor of Omahan Eugene Eppley.[234][235]

Transportation

Omaha's central role in the history of transportation across America earned it the nickname "Gate City of the West."[1] Despite President Lincoln's decree that Council Bluffs, Iowa, be the starting point for the Union Pacific Railroad, construction began from Omaha on the eastern portion of the first transcontinental railroad.[236] By the middle of the 20th century, Omaha was served by almost every major railroad. Today, the Omaha Rail and Commerce Historic District celebrates this connection, along with the listing of the Burlington Train Station and the Union Station on the National Register of Historic Places. First housed in the former Herndon House, the Union Pacific Railroad's corporate headquarters have been in Omaha since the company began.[237] Their new headquarters, the Union Pacific Center, was opened in Downtown Omaha in 2004. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service through Omaha. There is Greyhound lines in Omaha

Omaha's position as a transportation center was finalized with the 1872 opening of the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge linking the transcontinental railroad to the railroads terminating in Council Bluffs.[238] In 1888, the first road bridge, the Douglas Street Bridge, opened. In the 1890s, the Illinois Central drawbridge opened as the largest bridge of its type in the world. Omaha's Missouri River road bridges are now entering their second generation, including the Works Progress Administration-financed South Omaha Bridge, now called Veteran's Memorial Bridge, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2006, Omaha and Council Bluffs announced joint plans to build the Missouri River Pedestrian Bridge, which is expected to become a city landmark at its scheduled opening in November 2008.[239]

Today, the primary mode of transportation in Omaha is by automobile, with I-80, I-480, I-680, I-29, and U.S. Route 75 (JFK Freeway and North Freeway) providing freeway service across the metropolitan area.[240] The expressway along West Dodge Road (U.S. Route 6 and Nebraska Link 28B) and U.S. Route 275 has been upgraded to freeway standards from I-680 to Fremont. City owned Metro Area Transit provides public bus service to hundreds of locations throughout the Metro.

A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Omaha 21st most walkable of fifty largest U.S. cities.[241] There is an extensive trail system throughout the city for walkers, runners, bicyclists, and other pedestrian modes of transportation.

Omaha is laid out on a grid plan, with 12 blocks to the mile with a North to South house numbering system.[242] Omaha is the location of a historic boulevard system designed by H.W.S. Cleveland who sought to combine the beauty of parks with the pleasure of driving cars.[243] The historic Florence and Fontenelle Boulevards, as well as the modern Sorenson Parkway, are important elements in this system.[244]

Eppley Airfield, Omaha's airport, serves the region with over 4.2 million passengers in 2006.[245] United Airlines, Southwest Airlines, US Airways, Continental Airlines, Delta Air Lines, American Airlines, Frontier Airlines, and ExpressJet Airlines, serve the airport with direct and connecting service. Eppley is situated in East Omaha, with many users driving through Carter Lake, Iowa and getting a view of Carter Lake before getting there. General aviation airports serving the area are the Millard Municipal Airport, North Omaha Airport and the Council Bluffs Airport. Offutt Air Force Base continues to serve as a military airbase; it is located at the southern edge of Bellevue, which in turn lies immediately south of Omaha.

Notable people

Omaha is the historic and modern birthplace and home of notable politicians, actors, musicians, business leaders, sportsmen and cultural leaders. Numerous actors, including Gabrielle Union,[246] Montgomery Clift,[247] Fred Astaire and Adele Astaire,[248] Dorothy McGuire,[249] Marlon Brando[250] and Nick Nolte,[251] were born in Omaha. Academy Award winner Henry Fonda also grew up in Omaha. Marlon Brando's mother encouraged Henry Fonda to pursue acting at the Omaha Community Playhouse.[252] His son Peter Fonda also briefly lived in Omaha.[253] Mrs. Brando helped found the playhouse. His family's home still stands on South 33rd Street, a few blocks from the site of the first home of Gerald Ford.

Jazz Age magazine illustrator, Broadway scenic designer, and comic strip artist Russell Patterson was born in Omaha.[254] Tennis player Andy Roddick, former ATP ranking leader, was born in Omaha.[255] Omaha's rich musical history produced legends such as Wynonie Harris, Preston Love, Buddy Miles, Sara Olson, Calvin Keys, Eugene McDaniels and others.[256] Members of 311[257] and Bright Eyes[258] are part of the modern music scene. Chip Davis and Mannheim Steamroller began in and still headquarter out of Omaha.[259]

Warren Buffett, in 2008 the richest person in the world, lives in Omaha where he made his fortune in business.[260] Two native sons who achieved prominence nationally were born in Omaha, with their families moving away shortly thereafter.

The Gerald Ford birthplace site memorializes the 38th President.

African American activist and son of a Baptist minister, Malcolm X, first known as Malcolm Little, was also born in Omaha. Joining dozens of other important Omaha Landmarks, the Malcolm X House Site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Steve Borden (Sting) was born in Omaha while Ted DiBiase billed as born in Omaha.

Gale Sayers, a football player for the Chicago Bears was raised in Omaha graduating from an Omaha high school.

Alexander Payne, American film director and screenwriter was born and raised in Omaha.

Sister cities

Omaha has six sister cities:[261]

Braunschweig (Germany)

Braunschweig (Germany) Naas (Ireland)

Naas (Ireland) Shizuoka (Japan)

Shizuoka (Japan) Šiauliai (Lithuania)

Šiauliai (Lithuania) Xalapa-Enriquez (Mexico)

Xalapa-Enriquez (Mexico) Yantai (China)

Yantai (China)

References

- ^ a b Mullens, P.A. (1901) Biographical Sketches of Edward Creighton and John A. Creighton. Creighton University. p. 24.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (1 March 2011). "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Nebraska's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting". http://2010.census.gov/news/releases/operations/cb11-cn57.html. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. http://geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Boettcher, Ross. "Mutual returns to Fortune 500". Omaha World-Herald. April 16, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Kroll, L. "Special report: The World's Billionaires", Forbes magazine. March 5, 2008.

- ^ Mathews, J.J. (1961) The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters. University of Oklahoma Press. pages 110, 128, 140, 282.

- ^ (1987) "Fort Atkinson Chronology", NEBRASKAland Magazine. p. 34–35.

- ^ Morton, J.S., Watkins, A. and Miller, G.L. (1911) "Fur trade", Illustrated History of Nebraska: A History of Nebraska from the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region, with Steel Engravings, Photogravures, Copper Plates, Maps and Tables. Western Publishing and Engraving Company. p. 53.

- ^ "Fort Atkinson", Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 5/28/08.

- ^ Andreas, A.T. (1882) "Washington County", History of the State of Nebraska. Chicago, IL: Western Historical Company. Retrieved 4/28/08.

- ^ "Cutler's Park Marker", Florence Historical Society. Retrieved 5/28/08.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cotrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 6.

- ^ Royce, C.C. (1899) "Indian Land Cessions in the United States," in Powell, J.W. 18th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1896–97, Part 2, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- ^ Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration. (1970) Nebraska: A Guide to the Cornhusker State. Nebraska State Historical Society. p. 241.

- ^ Hickey, D.R., Wunder, S.A. and Wunder, J.R. (2007) Nebraska Moments: New Edition. University of Nebraska Press. p. 147.

- ^ Sheldon, A.E. (1904) "Chapter VII: Nebraska Territory," Semi-Centennial History of Nebraska. Lincoln, NE: Lemon Publishing. p. 58.

- ^ Andreas, A.T. (1882) "Douglas County", History of the State of Nebraska. Chicago, IL: Western Historical Company. p. 841.

- ^ "More about Nebraska statehood, the location of the capital and the story of the commissioner's homes," Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 12/14/08.

- ^ Baumann, L. Martin, C., Simpson, S. (1990) Omaha's Historic Prospect Hill Cemetery: A History of Prospect Hill Cemetery with Biographical Notes on Over 1400 People Interred Therein. Prospect Hill Cemetery Historical Development Foundation.

- ^ Federal Writers Project. (1939) Nebraska. Nebraska State Historical Society. p. 239.

- ^ Nebraska Territory Legislative Assembly. (1858) House Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Nebraska. Volume 5. p. 113.

- ^ Historic Prospect Hill – Omaha's Pioneer Cemetery. Nebraska Department of Education. Retrieved 7/7/07.

- ^ Federal Writers Project. (1939) Nebraska: A guide to the Cornhusker state. Nebraska State Historical Society. p. 219–232.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 64.

- ^ Union Pacific Railroad Company. (1867) The Union Pacific Railroad Company: Chartered by the United States: Progress of Their Road West from Omaha, Nebraska, Across the Continent: Making, with Its Connections, an Unbroken Line from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean: Five Hundred Miles Completed October 25, 1867. Brown & Hewitt, Printers. p. 5.

- ^ Wishart, D.J. (2004) Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press. p. 209.

- ^ Dunbar, S. (1915) A History of Travel in America: Being an Outline of the Development in Modes of Travel from Archaic Vehicles of Colonial Times to the Completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad: the Influence of the Indians on the Free Movement and Territorial Unity of the White Race. Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1915. p. 1350. Retrieved 9/25/08.

- ^ Larsen, L. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 73

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 142.

- ^ Taylor, Q. (1999) In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 204.

- ^ Morton, J.S. and Watkins, A. (1918) "Chapter XXXV: Greater Omaha," History of Nebraska: From the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region. Lincoln, NE: Western Publishing and Engraving Company. p. 831.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers. (1888) Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers to the Secretary of War for the Year. GPO. p. 309. Retrieved 4/11/08.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 94–95.

- ^ Folsom, B.W. (1999) No More Free Markets Or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900–1924. Lexington Books. p. 59.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 183–184.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 183.

- ^ "The strike at Omaha", The New York Times. March 12, 1882.

- ^ Bristow, D.L. (2002)A Dirty, Wicked Town. Caxton Press. p. 253.

- ^ "About the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition". Omaha Public Library. Retrieved 9/5/08.

- ^ Larsen, L. and Cottrell, B. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 43.

- ^ Larsen and Cotrell. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 135.

- ^ "Cudahy Kidnapping". Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 9/25/07.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 172.

- ^ "South Omaha mob wars on Greeks", The New York Times. February 22, 1909. Retrieved 5/25/08.

- ^ Nebraska Writers Project. (1940) The Negroes of Nebraska. Works Progress Administration. Woodruff Printing Company. p. 45.

- ^ "Easter came early in 1913", NOAA National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office. Retrieved 9/6/08.

- ^ (1994) Street of Dreams. (VHS) Nebraska Public Television.

- ^ Leighton, G.R. (1939) Five Cities: The Story of Their Youth and Old Age. Ayer Publishing. p. 212.

- ^ Salzman, J., Smith, D.J. and West, C. (1996) Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Macmillan Library Reference. p. 1974.

- ^ "Nebraska National Register Sites in Douglas County." Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 4/30/07.

- ^ (2006) Economic Impact Analysis: Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska. United States Air Force. Retrieved 5/28/08.

- ^ (2001) "State's top community development projects honored", Nebraska Department of Economic Development. Retrieved 4/7/07.

- ^ (2004) "125 years of memorable moments," The Creightonian Online. 83(19). Retrieved 7/23/07.

- ^ Wishart, D.J. (2004) Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press. p. 72.

- ^ Bednarek, R.D. (1992) The Changing Image of the City: Planning for Downtown Omaha, 1945–1973. University of Nebraska Press, 1992 p. 57.

- ^ Luebtke, F.C. (2005) Nebraska: An Illustrated History. University of Nebraska Press. p. 372.

- ^ (2006) NAACP v. Heineman. NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved 5/28/08.

- ^ Alexander, D. (1993) Natural Disasters. CRC Press. p. 183.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 296.

- ^ "W. Dale Clark Library", Omaha Public Library. Retrieved 8/25/08.

- ^ Gratz, R.B. (1996) The Living City: How America's Cities Are Being Revitalized by Thinking Small in a Big Way. John Wiley and Sons. p. v.

- ^ "Renovation of the Historic Livestock Exchange Building in Omaha", US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved 6/22/07.

- ^ Bednarek, J.R.D. (1992) The Changing Image of the City: Planning for Downtown Omaha, 1945–1973. University of Nebraska Press. p. 56.

- ^ Stempel, J. (2008) "Omaha bets on NoDo to extend downtown revival", Reuters. May 6, 2008. Retrieved 5/28/08.

- ^ Kynaski, J. "West Dodge keeps booming," Omaha World-Herald. January 16, 2006.

- ^ Sindt, R.P. and Shultz, S. "Can Omaha Fill More Condos? City Picks Downtown Developer For Project", Omaha World-Herald. December 14, 2005. Retrieved 9/21/08.

- ^ Market Segmentation: The Omaha Condominium Market, University of Nebraska at Omaha. Retrieved 9/21/08.

- ^ Jordan, S. (January 8, 2009) "Blue Cross building new Omaha headquarters", Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved 1/16/09.

- ^ (2006) "Mutual of Omaha Unveils Midtown Crossing at Turner Park Development". Mutual of Omaha website. Retrieved 5/18/07.

- ^ (2007)Urban Design Element Implementation Measures. OmahaByDesign. p. 6. Retrieved 9/26/08.

- ^ "Thousands Watch Bob Kerrey Bridge Lighting Ceremony", KETV. September 13, 2008. Retrieved 9/21/08.

- ^ "Riverfront Place – ‘Unique New Urban Neighborhood’", City of Omaha. November 5, 2003. Retrieved 9/21/08.

- ^ "Council Bluffs Steps Up Riverfront Plans", WOWT. September 12, 2008. Retrieved 9/21/08.

- ^ 2008 United States Olympic Swim Team. USASwimming.org. Retrieved 12/9/08.

- ^ 2008 Olympia Team Trials. USASwimming.org. Retrieved 5/27/08.

- ^ "Omaha Sports Commission Releases Ticket Information for 2008 U.S. Olympic Team Trials for Swimming", Omaha Sports Commission. Retrieved 8/30/08.

- ^ Larsen, L.H. and Cottrell, B.J. (1997) The Gate City: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. p. 149.

- ^ "May 2007 OES Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Definitions." Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 9/5/08.