- Yankee

-

This article is about the term. For other uses, see Yankee (disambiguation).

The term Yankee (sometimes shortened to Yank) has several interrelated and often pejorative meanings, usually referring to people originating in the northeastern United States, or still more narrowly New England, where application of the term is largely restricted to descendants of the English settlers of the region.[1]

The meaning of Yankee has varied over time. In the 18th century, it referred to residents of New England descended from the original English settlers of the region. Mark Twain, in the following century, used the word in this sense in his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, published in 1889. As early as the 1770s, British people applied the term to any person from what became the United States. In the 19th century, Americans in the southern United States employed the word in reference to Americans from the northern United States (though not to recent immigrants from Europe; thus a visitor to Richmond, Virginia, in 1818 commented, "The enterprising people are mostly strangers; Scots, Irish, and especially New England men, or Yankees, as they are called").[2]

Outside the United States, Yankee is slang for anyone from the United States. The truncated form Yank is especially popular among Britons, and may sometimes be considered offensive or disapproving.[3]

Contents

Origins and history of the word

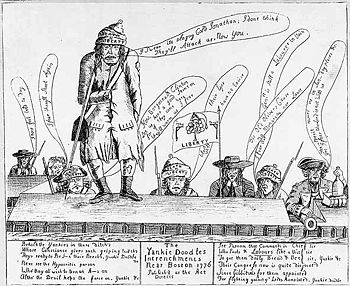

Loyalist newspaper cartoon from Boston in 1775 ridicules "Yankie Doodles" militia who have encircled the city

Loyalist newspaper cartoon from Boston in 1775 ridicules "Yankie Doodles" militia who have encircled the city

Early usage

The origins of the term are uncertain. In 1758, British General James Wolfe made the earliest recorded use of the word Yankee to refer to people from what was to become the United States, referring to the New England soldiers under his command as Yankees: "I can afford you two companies of Yankees, and the more because they are better for ranging and scouting than either work or vigilance."[4] Later British use of the word often was derogatory, as in a cartoon of 1775 ridiculing "Yankee" soldiers.[4] New Englanders themselves employed the word in a neutral sense: the "Pennamite-Yankee War", for example, was the name given to a series of clashes in 1769 over land titles in Pennsylvania, in which the "Yankees" were the Connecticut claimants.

Faulty theories

Many faulty etymologies have been devised for the word, including one by a British officer in 1789 who said it derived from the Cherokee word eankke, meaning "coward" -- but no such word exists in Cherokee.[5] Etymologies purporting an origin in languages of the aboriginal inhabitants of the United States are not well received by linguists. One such surmises that the word is borrowed from the Wyandot (called Huron by the French) pronunciation of the French l'anglais (meaning "the Englishman" or "the English (language)"), sounded as Y'an-gee.[5][6] Writing in 1819, the Rev. John Heckewelder stated his belief that the name grew out of the attempts by Native Americans to pronounce the word English.[5] The U.S. novelist James Fenimore Cooper supported this view in his 1841 book The Deerslayer. Linguists, however, do not support any Indian origins.[5]

Dutch origins

Most linguists look to Dutch sources, noting the extensive interaction between the colonial Dutch in New Netherland (now largely New York state, New Jersey, Delaware and western Connecticut) and the colonial English in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. The Dutch given names Jan and Kees were and still are common, and the two sometimes are combined into a single name, Jan-Kees. The word Yankee is a variation that could have referred to English settlers moving into previously Dutch areas.[5]

Michael Quinion and Patrick Hanks argue[7] that the term refers to the Dutch nickname and surname Janneke (from Jan and the diminutive -eke, meaning "Little John" or Johnny in Dutch), Anglicized to Yankee (in Dutch, the letter "J" is pronounced the same as the English consonantal "Y" sound) and "used as a nickname for a Dutch-speaking American in colonial times". By extension, the term could have grown to include non-Dutch colonists as well.

H. L. Mencken[8] explained the derogatory term John Cheese was often applied to the early Dutch colonists, who were famous for their cheeses. An example would be a British soldier commenting on a Dutch man "Here comes a John Cheese". The Dutch translation of John Cheese is Jan Kaas; the two words thus would sound somewhat like Yahn-kees and could have given birth to the present term. Added to that, the common black-and-white dairy cow had been bred in the Dutch provinces of North Holland and Friesland, then introduced to the North American colony of New Amsterdam (in the mid-1600s) further strengthening the association of cheese with the Dutch.

Historic uses

Canadian usage

An early use of the term outside the United States was in the creation of Sam Slick, the "Yankee Clockmaker", in a column in a newspaper in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1835. The character was a plain-talking American who served to poke fun at Nova Scotian customs of that era, while, initially, trying to urge the old-fashioned Canadians to be as clever and hard-working as Yankees. The character, developed by Thomas Chandler Haliburton, evolved over the years between 1836 and 1844 in a series of publications.[9]

Damn Yankee

The damned Yankee usage dates from 1812.[4] During and after the American Civil War (1861–1865) Confederates popularized it as a derogatory term for their Northern enemies. In an old joke, a Southerner alleges, "I was twenty-one years old before I learned that 'damn' and 'yankee' were separate words." It became a catch phrase, often used humorously for Yankees visiting the South, as in the mystery novel, Death of a Damn Yankee: A Laura Fleming Mystery (2001) by Toni Kelner. Another popular although facetious saying is that "a yankee is someone from the North who comes to the South for a visit and then goes back. A damn Yankee is someone from the North who comes to the South and stays there."

Yankee Doodle

Perhaps the most pervasive influence on the use of the term throughout the years has been the song "Yankee Doodle", which was popular during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) as, following the battles of Lexington and Concord, it was broadly adopted by American rebels. Today, "Yankee Doodle" is the official "state song" of Connecticut.[10]

Yankee cultural history

The term Yankee now may mean any resident of New England or of any of the Northeastern United States. The original Yankees diffused widely across the northern United States, leaving their imprints in New York, the Upper Midwest, and places as far away as Seattle, San Francisco, and Honolulu.[11] Yankees typically lived in villages consisting of clusters of separate farms. Village life fostered local democracy, best exemplified by the Open Town Meeting form of government which still exists today in parts of New England. Village life also stimulated mutual oversight of moral behavior, and emphasized civic virtue. From the New England seaports of Boston, Salem, Providence, and New London, among others, the Yankees built an international trade, stretching to China by 1800. Much of the profit from trading was reinvested in the textile and machine tools industries.[12]

In religion, New England Yankees originally followed the Puritan tradition, as expressed in Congregational churches; beginning in the late colonial period, however, many became Episcopalians, Methodists, Baptists, or, later, Unitarians. Straight-laced 17th century moralism as described by novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne faded in the 18th century. The First Great Awakening (under Jonathan Edwards and others) in the mid-18th century and the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century (under Charles Grandison Finney, among others) emphasized personal piety, revivals, and devotion to civic duty. Theologically, Arminianism replaced the original Calvinism. Horace Bushnell introduced the idea of Christian nurture, through which children would be brought to religion without revivals.

After 1800, Yankees (along with some Quakers and others) spearheaded most reform movements, including those for abolition of slavery, temperance in use of alcohol, increase in women's political rights, and improvement in women's education. Emma Willard and Mary Lyon pioneered in the higher education of women, while Yankees comprised most of the reformers who went South during Reconstruction in the late 1860s to educate the Freedmen.[13]

Politically, Yankees, who dominated New England, much of upstate New York, and much of the upper Midwest, were the strongest supporters of the new Republican party in the 1860s. This was especially true for the Congregationalists and Presbyterians among them and (after 1860), the Methodists. A study of 65 predominantly Yankee counties showed that they voted only 40% for the Whigs in 1848 and 1852, but became 61–65% Republican in presidential elections of 1856 through 1864.[14]

Ivy League universities, particularly Harvard and Yale, as well as "Little Ivy" liberal arts colleges, remained bastions of old Yankee culture until well after World War II.

President Calvin Coolidge was a striking example of the Yankee stereotype. Coolidge moved from rural Vermont to urban Massachusetts and was educated at elite Amherst College. Yet his flint-faced, unprepossessing ways and terse rural speech proved politically attractive: "That Yankee twang will be worth a hundred thousand votes", explained one Republican leader.[15] Coolidge's laconic ways and dry humor was characteristic of stereotypical rural "Yankee humor" at the turn of the 20th century.[16]

The fictional character Thurston Howell, III, of Gilligan's Island, a graduate of Harvard, typifies the old Yankee elite in a comical way.

By the opening of the 21st century, systematic Yankee ways had permeated the entire society through education. Although many observers from the 1880s onward predicted that Yankee politicians would be no match for new generations of ethnic politicians, the presence of Yankees at the top tier of modern American politics was typified by Presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush, and by Democratic National Committee chairman Howard Dean (as well, to some observers, by 2004 Democratic presidential nominee Senator John Forbes Kerry, descendant through his mother, of the Scottish Forbes family, which emigrated to Massachusetts the 1750s). President Barack Obama is of Yankee descent on his mother's side; his high school was Punahou School, founded to serve the children of Yankee missionaries to Hawaii.[17]

Contemporary uses

In the United States

Within the United States, the term Yankee can have many different contextually and geographically dependent meanings.

Traditionally, Yankee was most often used to refer to a New Englander descended from the original settlers of the region (thus often suggesting Puritanism and thrifty values).[18] By the mid-20th century, some speakers applied the word to any American born north of the Mason–Dixon Line, though usually with a specific focus still on New England. New England Yankee might be used to differentiate.[19] However, within New England itself, the term still refers more specifically to old-stock New Englanders of English descent. The term "WASP", in use since the 1960s, refers to all Protestants of English ancestry, including both Yankees and Southerners, though its meaning is often extended to refer to any Protestant white American.

The term Swamp Yankee is sometimes used in rural Rhode Island, Connecticut, and southeastern Massachusetts to refer to Protestant farmers of moderate means and their descendants (in contrast to richer or urban Yankees); "swamp Yankee" is often regarded as a derogatory term.[20] Scholars note that the famous Yankee "twang" survives mainly in the hill towns of interior New England, though it is disappearing even there.[21] The most characteristic Yankee food was pie; Yankee author Harriet Beecher Stowe in her novel Oldtown Folks celebrated the social traditions surrounding the Yankee pie.

In the southern United States, the term is sometimes used in derisive reference to any Northerner, especially one who has migrated to the South; a more polite term is Northerner. Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas pointed out as late as 1966, "The very word 'Yankee' still wakens in Southern minds historical memories of defeat and humiliation, of the burning of Atlanta and Sherman's march to the sea, or of an ancestral farmhouse burned by Cantrill's raiders."[22] In Ambrose Bierce's The Devil's Dictionary Yankee is defined in this manner:

- "n. In Europe, an American. In the Northern States of our Union, a New Englander. In the Southern States the word is unknown. (See DAMNYANK.)"

A humorous aphorism attributed to E. B. White summarizes these distinctions:

-

- To foreigners, a Yankee is an American.

- To Americans, a Yankee is a Northerner.

- To Northerners, a Yankee is an Easterner.

- To Easterners, a Yankee is a New Englander.

- To New Englanders, a Yankee is a Vermonter.

- And in Vermont, a Yankee is somebody who eats pie for breakfast.

Another variant of the aphorism replaces the last line with: "To a Vermonter, a Yankee is somebody who still uses an outhouse." There are several other folk and humorous etymologies for the term.

One of Mark Twain's novels, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, popularized the word as a nickname for residents of Connecticut.

It is also the official team nickname of a Major League Baseball franchise, the New York Yankees - ironically, the team is deeply unpopular, if not hated, in "Yankee" New England, as the Yankees and the region's team of choice, the Boston Red Sox, have one of the most bitter rivalries in all of professional sports. It is common to hear Red Sox fans chant "Yankees Suck" at Red Sox baseball games and after Red Sox team celebrations.

A film about Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was titled The Magnificent Yankee.

The title of the 1955 musical Damn Yankees refers specifically to the New York Yankees baseball team but also echoes the older cultural term. Similarly, a book about the ball club echoes the title of the Holmes film: The Magnificent Yankees.

In other English-speaking countries

In English-speaking countries outside the United States, especially in Britain, Australia, Canada,[23] Ireland,[24] and New Zealand, Yankee, almost universally shortened to Yank, is used as a derogatory, playful or colloquial term for Americans.

In certain Commonwealth countries, especially Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, Yank has been in common use since at least World War II, when hundreds of thousands of Americans were stationed in Britain, Australia and New Zealand. Depending on the country, Yankee may be considered mildly derogatory.[25]

In other parts of the world

In some parts of the world, particularly in Latin American countries and in East Asia, yankee or yanqui (phonetic Spanish spelling of the same word) is sometimes associated with anti-Americanism and used in expressions such as "Yankee go home" or "we struggle against the yanqui, enemy of mankind" (words from the Sandinista anthem). In Spain, however, just as in Great Britain or other English-speaking areas, the term (yanqui in Spanish spelling) is simply used to refer to someone from the US, whether colloquially, playfully or derogatively, with no particular emphasis on the latter use. This can also be the case in many countries of Latin America. In Venezuelan Spanish there is the word pitiyanqui, derived ca. 1940 around the oil industry from petty yankee or petit yanqui,[26] a derogatory term for those who profess an exaggerated and often ridiculous admiration for anything from the United States.

In the late 19th century, the Japanese were called "the Yankees of the East" in praise of their industriousness and drive to modernization.[27] In Japan since the late 1970s, the term Yankī has been used to refer to a type of delinquent youth.[28]

In Korea, the word "Yankee" is often misused to denote anyone who is white Caucasian, and also some non-white Caucasian from countries which are perceived to be predominantly 'white', including, but not limited to, England, Australia, Canada, and most of Europe. It is commonly understood and used as a mild derogatory term against "white" people; Thus, it is not uncommon to see Korean people calling unrelated people such as French or Swedish "Yankee(s)".

In Finland, the word jenkki (yank) is sometimes used to refer to any U.S. citizen, and with the same group of people Jenkkilä (Yankeeland) refers to the United States itself. It is not considered offensive or anti-U.S., but rather a spoken language expression.[29] However, more commonly a U.S. citizen is called amerikkalainen (American) or yhdysvaltalainen ('United Statesian') and the country itself 'Amerikka' or 'Yhdysvallat'.

The variant Yankee Air Pirate was used during the Vietnam War in North Vietnamese propaganda to refer to the United States Air Force.

In Iceland, the word kani is used for Yankee or Yank in the mildly derogatory sense. When referring to residents of the United States, norðurríkjamaður, or more commonly bandaríkjamaður, is used.

In Polish, the word jankes can refer to any U.S. citizen, has little pejorative connotation if at all, and its use is somewhat obscure (it is mainly used to translate the English word Yankee in a less formal context, e.g. in a movie about the American Civil War).

In Sweden the word is translated to jänkare. The word is not itself a negative expression, though it can of course be used as such depending on context. When a Swedish person uses the word jänkare, it usually refers to cars from America, but could also be used as a slang term for any U.S. citizen.

Joshua Slocum, in his 1899 book Sailing Alone Around the World refers to Nova Scotians as being the only or true Yankees. It thus may be implied, as he himself was a Nova Scotian, that he had pride in his ancestry. Yankee in this instance, instead of connoting a form of derision, is therefore a form of praise; perhaps relevant to the hardy seagoing people of the East Coast at that time.

Yankee is the code word for the letter "Y" in the NATO phonetic alphabet. In this usage, it is referred to in the title of the 2002 Wilco album "Yankee Hotel Foxtrot."

See also

- 26th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade (Yankee Division)

- Jonkheer

- Yankee Doodle Dandy

- Yankee ingenuity

- Yonki

References

- ^ Ruth Schell, "Swamp Yankee", American Speech, vol. 38, No.2 (1963), pp. 121–123. accessed through JSTOR

- ^ See Mathews, (1951) pp 1896-98 and Oxford English Dictionary, quoting M. Birkbeck

- ^ "Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary Online". Cambridge University Press. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/yank_2#yank_2__3. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Mathews (1951) p 1896

- ^ a b c d e The Merriam-Webster new book of word histories (1991) pp. 516-517.

- ^ Mathews (1951) p. 1896.

- ^ Review of Quinion, Michael Port Out, Starboard Home

- ^ Yankee from Words@Random

- ^ Cogswell, F. (2000).Haliburton, Thomas Chandler. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Volume IX 1861-1870. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved on: 2011-08-15.

- ^ See Connecticut State Library, "Yankee Doodle, the State Song of the State of Connecticut"

- ^ Mathews (1909), Holbrook (1950)

- ^ Knights (1991)

- ^ Taylor (1979)

- ^ Kleppner p 55

- ^ William Allen White, A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge (1938) p. 122.

- ^ Arthur George Crandall, New England Joke Lore: The Tonic of Yankee Humor, (F.A. Davis Company, 1922).

- ^ Smith (1956)

- ^ Bushman, (1967)

- ^ http://www.islandpacket.com/2010/12/23/1489118/a-white-christmas-so-close-but.html

- ^ Ruth Schell, "Swamp Yankee", American Speech, vol. 38, No.2 (1963), pp. 121–123. accessed through JSTOR

- ^ Fisher, Albion's Seed p 62; Edward Eggleston, The Transit of Civilization from England to the U.S. in the Seventeenth Century. (1901) p. 110; Fleser (1962)

- ^ Fulbright's statement of March 7, 1966, quoted in Randall Bennett Woods, "Dixie's Dove: J. William Fulbright, The Vietnam War and the American South," The Journal of Southern History, vol. 60, no. 3 (Aug., 1994), p. 548.

- ^ J. L. Granatstein, Yankee Go Home: Canadians and Anti-Americanism (1997)

- ^ Mary Pat Kelly, Home Away from Home: The Yanks in Ireland (1995)

- ^ John F. Turner and Edward F. Hale, eds. Yanks Are Coming: GIs in Britain in WWII (1983), primary documents; ; Eli Daniel Potts, Yanks Down Under, 1941-1945: The American Impact on Australia (1986); Harry Bioletti, The Yanks are coming: The American invasion of New Zealand, 1942-1944 (1989)

- ^ A Little Insult Is All the Rage in Venezuela: ‘Pitiyanqui’, The New York Times.

- ^ William Eleroy Curtis, The Yankees of the East, Sketches of Modern Japan. (New York: 1896).

- ^ Daijirin dictionary, Yahoo! Dictionary

- ^ . See comments on H-South by Seppo K J Tamminen at

Further reading

- Beals, Carleton; Our Yankee Heritage: New England's Contribution to American Civilization (1955) online

- Conforti, Joseph A. Imagining New England: Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century (2001) online

- Bushman, Richard L. From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690–1765 (1967)

- Ellis, David M. "The Yankee Invasion of New York 1783–1850". New York History (1951) 32:1–17.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1989), Yankees comprise one of the four

- Gjerde; Jon. The Minds of the West: Ethnocultural Evolution in the Rural Middle West, 1830–1917 (1999) online

- Gray; Susan E. The Yankee West: Community Life on the Michigan Frontier (1996) online

- Handlin, Oscar. "Yankees", in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, ed. by Stephan Thernstrom, (1980) pp 1028–1030.

- Hill, Ralph Nading. Yankee Kingdom: Vermont and New Hampshire. (1960).

- Holbrook, Stewart H. Yankee Exodus: An Account of Migration from New England (1950)

- Holbrook, Stewart H.; Yankee Loggers: A Recollection of Woodsmen, Cooks, and River Drivers (1961)

- Hudson, John C. "Yankeeland in the Middle West", Journal of Geography 85 (Sept 1986)

- Jensen, Richard. "Yankees" in Encyclopedia of Chicago (2005).

- Kleppner; Paul. The Third Electoral System 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures University of North Carolina Press. 1979, on Yankee voting behavior

- Knights, Peter R.; Yankee Destinies: The Lives of Ordinary Nineteenth-Century Bostonians (1991) online

- Mathews, Lois K. The Expansion of New England (1909).

- Piersen, William Dillon. Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (1988)

- Power, Richard Lyle. Planting Corn Belt Culture (1953), on Indiana

- Rose, Gregory. "Yankees/Yorkers", in Richard Sisson ed, The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (2006) 193–95, 714–5, 1094, 1194,

- Sedgwick, Ellery; The Atlantic Monthly, 1857–1909: Yankee Humanism at High Tide and Ebb (1994) online

- Smith, Bradford. Yankees in Paradise: The New England Impact on Hawaii (1956)

- Taylor, William R. Cavalier and Yankee: The Old South and American National Character (1979)

- WPA. Massachusetts: A Guide to Its Places and People. Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration of Massachusetts (1937).

Linguistic

- Davis, Harold. "On the Origin of Yankee Doodle", American Speech, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Apr., 1938), pp. 93–96 in JSTOR

- Fleser, Arthur F. "Coolidge's Delivery: Everybody Liked It." Southern Speech Journal 1966 32(2): 98–104. Issn: 0038-4585

- Kretzschmar, William A. Handbook of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (1994)

- Lemay, J. A. Leo "The American Origins of Yankee Doodle", William and Mary Quarterly 33 (Jan 1976) 435–64 in JSTOR

- Logemay, Butsee H. "The Etymology of 'Yankee'", Studies in English Philology in Honor of Frederick Klaeber, (1929) pp 403–13.

- Mathews, Mitford M. A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles (1951) pp 1896 ff for elaborate detail

- Mencken, H. L. The American Language (1919, 1921)

- The Merriam-Webster new book of word histories (1991)

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Schell, Ruth. "Swamp Yankee", American Speech, 1963, Volume 38, No.2 pg. 121–123. in JSTOR

- Sonneck, Oscar G. Report on "the Star-Spangled Banner" "Hail Columbia" "America" "Yankee Doodle" (1909) pp 83ff online

- Stollznow, Karen. 2006. "Key Words in the Discourse of Discrimination: A Semantic Analysis. PhD Dissertation: University of New England., Chapter 5.

External links

Ethnic and religious slurs White people GeneralAmericansItaliansJewsChrist killer • Kike • JAP • ŻydokomunaBlack people GeneralAsians ABC • Ah Beng • Chinaman • Ching chong • Chink/chinky • Coolie • Gook • Jap • Jjokbari • Jook-sing • Sangokujin • ShinaArabsQadiani (Ahmadis) • Rafida (Shi'ites)Other Ajam (non-Arabs) • Batiniyya • Cholo (Mestizos) • Coonass (Cajuns) • Extracomunitario • Gâvur (non-Muslims) • Gentile (non-Jews) • Goy (non-Jews) • Infidel (non-Muslims) • Kafir (non-Muslims) • Kanaka (Pacific Islanders) • Kanake • Redskin (Native Americans) • Shegetz (non-Jewish boy or man) • Shiksa (non-Jewish women) • Squaw (Native American women)Categories:- American culture

- American regional nicknames

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.