- Antidepressant

-

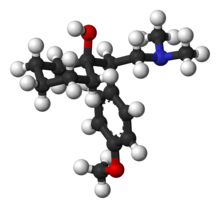

Fluoxetine (Prozac), an SSRI

Fluoxetine (Prozac), an SSRI

An antidepressant is a psychiatric medication used to alleviate mood disorders, such as major depression and dysthymia and anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder. According to Gelder, Mayou &*Geddes (2005) people with a depressive illness will experience a therapeutic effect to their mood; however, this will not be experienced in healthy individuals. Drugs including the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are most commonly associated with the term. These medications are among those most commonly prescribed by psychiatrists and other physicians, and their effectiveness and adverse effects are the subject of many studies and competing claims. Many drugs produce an antidepressant effect, but restrictions on their use have caused controversy and off-label prescription is a risk, despite claims of superior efficacy.

Opioids were used to treat major depression until the late 1950s. Amphetamines were used until the mid 1960s. Prescribing opioids or amphetamines for depression falls into a legal grey area. Research has only rarely been conducted into the therapeutic potential of opioid derivatives for depression in the past sixty years, whereas amphetamines have found a thriving market for conditions as widely arrayed as attention deficit disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity, and continue to be studied for myriad applications. Both opioids and amphetamines induce a therapeutic response very quickly, showing results within twenty-four to forty-eight hours; the therapeutic ratios for both opioids and amphetamines are greater than those of the tricyclic anti-depressants. In some of this little, heavily restricted research, the opioid buprenorphine has shown the greatest potential for treating severe, treatment-resistant depression of any known pharmaceutical in a small study that is generally recognized and was published in 1995, but has never been pursued due to the social stigma attached to opioids in addition to that attached to mental illness in America.[1]

Most typical antidepressants have a delayed onset of action (2–6 weeks) and are usually administered for anywhere from months to years. Despite the name, antidepressants are often used controversially, and with a dearth of empirical evidence to support their indication, off-label to treat other conditions, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorders, chronic pain, and some hormone-mediated disorders such as dysmenorrhea. Alone or together with anticonvulsants (e.g., Tegretol or Depakote), these medications can be used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance abuse by addressing underlying depression. Also, antidepressants have been used sometimes to treat snoring and migraines.

Other medications that are not usually called antidepressants, including antipsychotics in low doses[2] and benzodiazepines,[3] may be used to manage depression, although benzodiazepines cause a physical dependence to form. Stopping benzodiazepine treatment abruptly can cause unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. An extract of the herb St John's Wort is commonly used as an antidepressant, although it is labeled as a dietary supplement in some countries. The term antidepressant is sometimes applied to any therapy (e.g., psychotherapy, electro-convulsive therapy, acupuncture) or process (e.g., sleep disruption, increased light levels, regular exercise) found to improve a clinically depressed mood.

Inert placebos can have significant antidepressant effects, and so to establish a substance as an "antidepressant" in a clinical trial it is necessary to show superior efficacy to placebo.[4] A review of both published and unpublished trials submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found that the published trials had a 94% success in treating depression while the unpublished literature had below 50% success.[5] Combined, all studies showed 51% efficacy - only two points better than that of placebo.[5] The difference in effect between active placebos and several anti-depressants appeared small and strongly affected by publication bias.[5] There is some evidence to suggest that mirtazapine and venlafaxine may have greater efficacy than other antidepressants in the treatment of severe depression.[6]

Types

Main article: List of antidepressantsSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of antidepressants considered the current standard of drug treatment. A possible cause of depression is an inadequate amount of serotonin, a chemical used in the brain to transmit signals between neurons. SSRIs are said to work by preventing the reuptake of serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT) by the presynaptic neuron, thus maintaining higher levels of 5-HT in the synapse. Chemists Klaus Schmiegel and Bryan Molloy of Eli Lilly discovered the first SSRI, fluoxetine. This class of drugs includes:

- Citalopram (Celexa, Cipramil)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro, Cipralex, Seroplex, Lexamil)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem, Symbyax)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Aropax)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

- Vilazodone (Viibryd)

These antidepressants typically have fewer adverse effects than the tricyclics or the MAOIs, although such effects as drowsiness, dry mouth, nervousness, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, long-term weight gain and decreased ability to function sexually may occur. Some side effects may decrease as a person adjusts to the drug, but other side effects may be persistent.

Work by two researchers has called into question the link between serotonin deficiency and symptoms of depression, noting that the efficacy of SSRIs as treatment does not in itself prove the link.[7] Research indicates that these drugs may interact with transcription factors known as "clock genes",[8] which may play a role in the addictive properties of drugs (drug abuse), and possibly in obesity.[9][10]

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials published in the Archives of General Psychiatry showed that up to one-third of the 6-week effect of SSRI Treatment can be seen in the first week. The same study also found that patients treated with SSRIs were 64% more likely to achieve a 50% absolute reduction in HRSD than patients given a placebo.[11]

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a newer form of antidepressant that work on both norepinephrine and 5-HT. They typically have similar side effects to the SSRIs, though there may be a withdrawal syndrome on discontinuation that may necessitate dosage tapering. These include:

- Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq)

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- Milnacipran (Ixel)

- Venlafaxine (Effexor)

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs) form a newer class of antidepressants which purportedly work to increase norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and serotonin neurotransmission by blocking presynaptic alpha-2 adrenergic receptors while at the same time blocking certain serotonin receptors.[12] Side effects may include drowsiness, increased appetite, and weight gain.[13] Examples include:

- Mianserin (Tolvon)

- Mirtazapine (Remeron, Avanza, Zispin)

Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) reuptake inhibitors

Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) act via norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline). NRIs are thought to have a positive effect on the concentration and motivation in particular. These include:

- Atomoxetine (Strattera)

- Mazindol (Mazanor, Sanorex)

- Reboxetine (Edronax)

- Viloxazine (Vivalan)

Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors

Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors inhibit the neuronal reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine (noradrenaline).[14] These include:

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin, Zyban)

Selective serotonin reuptake enhancers

- Tianeptine (Stablon, Coaxil, Tatinol)

Norepinephrine-dopamine disinhibitors

Norepinephrine-dopamine disinhibitors (NDDIs) act by antagonizing the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor which normally acts to inhibit norepinephrine and dopamine release, thereby promoting outflow of these neurotransmitters.

- Agomelatine (Valdoxan, Melitor, Thymanax)

Tricyclic antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants are the oldest class of antidepressant drugs. Tricyclics block the reuptake of certain neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and serotonin. They are used less commonly now due to the development of more selective and safer drugs. Side effects include increased heart rate, drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, dizziness, confusion, and sexual dysfunction. Toxicity occurs at approximately ten times normal dosages; these drugs are often lethal in overdoses, as they may cause a fatal arrhythmia. However, tricyclic antidepressants are still used because of their effectiveness, especially in severe cases of major depression. These include:

Tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressants:

- Amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep)

- Clomipramine (Anafranil)

- Doxepin (Adapin, Sinequan)

- Imipramine (Tofranil)

- Trimipramine (Surmontil)

Secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants

- Desipramine (Norpramin)

- Nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl, Noritren)

- Protriptyline (Vivactil)

Antidepressant drugs differ in their relative toxicities. The most hazardous are monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclics. Features include arrhythmias, convulsions and cardiovascular effects. Management should be as active as necessary to reduce arrhythmia risk by aggressive correction of acidosis and use of sodium bicarbonate to shorten QRS duration if prolonged. Venlafaxine and citalopram are the most toxic of the newer drugs.[15]

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) may be used if other antidepressant medications are ineffective. MAOIs work by blocking the enzyme monoamine oxidase which breaks down the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). Because there are potentially fatal interactions between this class of medication and certain foods (particularly those containing tyramine), as well as certain drugs, classic MAOIs are rarely prescribed anymore. However, this does not apply to Emsam, the transdermal patch form of selegiline, which due to its bypassing of the stomach has a lesser propensity to induce such events.[16] MAOIs can be as effective as tricyclic antidepressants, although they are generally used less frequently because they have a higher incidence of dangerous side effects and interactions. A new generation of MAOIs has been introduced; moclobemide (Manerix), known as a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA), acts in a more short-lived and selective manner and does not require a special diet. The MAOI group of medicines include:

- Isocarboxazid (Marplan)

- Moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix)

- Phenelzine (Nardil)

- Selegiline (Eldepryl, Emsam)

- Tranylcypromine (Parnate)

Augmenter drugs

Some antidepressants have been found to work better in some patients when used in combination with another drug. Such "augmenter" drugs include:

- Buspirone (Buspar)

- Gepirone (Ariza)

- Nefazodone (Serzone)

- Tandospirone (Sediel)

- Trazodone (Desyrel)

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin/Zyban)

Tranquillizers and sedatives, typically the benzodiazepines, are prescribed to ease anxiety and promote sleep. Because of the high risk of dependency, these medications are intended only for short-term or occasional use. Medications are often used not for their primary functions, but to exploit what are normally side effects. Quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel) is designed primarily to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but frequently causes somnolence because of its affinity for histamine (H1 and H2) receptors, exploiting the same side effects as diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

Antipsychotics such as risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), and quetiapine (Seroquel) are prescribed as mood stabilizers and to treat anxiety. Their use as mood stabilizers is a recent phenomenon, and controversial among some patients.[citation needed] Antipsychotics, whether typical or atypical, may also be prescribed to augment an antidepressant, to increase the blood concentration of another drug, or to relieve the psychotic or paranoid symptoms that often accompany clinical depression. However, they can cause serious side effects, particularly at high dosages, including blurred vision, muscle spasms, restlessness, tardive dyskinesia, and weight gain.

Psychostimulants, such as amphetamine (Adderall), methylphenidate (Ritalin) or modafinil (Provigil, Alertec), are sometimes added to an antidepressant regimen.[17] Modafinil is unique in its effect on sleep: it increases alertness and reduces drowsiness while the patient is active, but does not inhibit normal sleep. Extreme caution must be used however with certain populations. Stimulants are known to trigger manic episodes in people suffering from bipolar disorder. Close supervision of those with substance abuse disorders is urged. Emotionally labile patients should avoid stimulants, as they exacerbate mood shifting. A review article published in 2007 found that psychostimulants "may" be effective in treatment-resistant depression with concomitant antidepressant therapy. A more certain conclusion could not be drawn due to substantial deficiencies in the studies available for consideration, and the "somewhat" contradictory nature of their results. However, the authors claim that psychostimulants are likely to have a higher level of clinical effectiveness under circumstances in which the patient will probably die soon, so rapid relief is of great importance. In this situation, the patient is likely to die before dependence on, or tolerance of the medication interferes with their care.[18]

Lithium remains the standard treatment for bipolar disorder and is often used in conjunction with other medications, depending on whether mania or depression is being treated. Lithium's potential side effects include thirst, tremors, light-headedness, nausea, and diarrhea. Some of the anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine (Tegretol), sodium valproate (Epilim), and lamotrigine (Lamictal), are also used as mood stabilizers, particularly in bipolar disorder. Both lithium and lamotrigine have also been studied and used to augment antidepressants in treatment-resistant unipolar depression.

Herbal

St. John's Wort is by far the most widely-used and well-studied herbal antidepressant. A number of other herbs have been used traditionally to treat depression and related ailments like anxiety, but the research on most of these treatments is sparse.[citation needed]

In a small (30 patient) double-blind randomized clinical trial, saffron (Crocus sativus L.) was to be equally effective with imipramine for treating mild to moderate depression. However, no other researchers have confirmed these results, nor has a larger population study been published.[19] Another small (40 patient) 8-week double-blind randomized trial found saffron to have a similar effect to fluoxetine (Prozac) in the treatment of mild to moderate depression, including a similar remission rate and similar rate of side effects.[20] Neither study has been confirmed in larger trials at other centers.

Several plants in the Salvia genus have been studied for antidepressant properties, although most of the research conducted so far has only been from mice and rat studies. Salvia elegans, also known as pineapple sage, is widely used in Mexican traditional medicine, and has been found in single study in mice to have antidepressant and antianxiety properties.[21] Salvia sclarea, also known as clary, is known to have an antidepressant-like effect in rats, which is thought to be explained by modulation of dopamine.[22]

Nutrients

Nutrition has been implicated as one of the causes and risk factors for depression, and accordingly, one approach to depression involves the use of nutritional supplements or changes in diet. A study of older adults found that poor nutrition was a strong predictor of depressive symptoms a year later.[23] A few nutrients have been studied directly for their antidepressant properties, both to treat and prevent depression, as well as related conditions such as anxiety.

Omega-3

Omega 3 fatty acids have been proposed as a treatment for depression, often suggested to be combined with other treatments. One small pilot study of childhood depression (ages 6–12) suggested that omega 3 may have therapeutic benefits for treating childhood depression.[24] A 2005 review of the scientific literature concluded that there were several different independent lines of evidence suggesting that omega-3 fatty acids play a role in depression, and that the theory of omega-3's role in depression was biologically plausible. The evidence includes a few double-blind randomized control trials, epidemiological studies linking low fish consumption (the primary source of omega-3) to increased rates of depression, and case-control and cohort studies of unipolar and postpartum depression indicating low blood levels of omega-3 in depressed patients.[25] A recent review of clinical studies of the effect of omega 3 fatty acids on depression has shown inconsistent results.[26]

Therapeutic efficacy

There is a large amount of research evaluating the potential therapeutic effects of antidepressants, whether through efficacy studies under experimental conditions (including randomized clinical trials) or through studies of "real world" effectiveness.[citation needed] A sufficient response to a drug is often defined as at least a 50% reduction in self-reported or observed symptoms, with a partial response often defined as at least a 25% reduction.[citation needed] The term remission indicates a virtual elimination of depression symptoms, albeit with the risk of a recurrence of symptoms or complete relapse. Full remission or recovery signifies a full sustained return to a "normal" psychological state with full functioning.[citation needed]

There has also been a great deal of study about whether antidepressants address the underlying causes of depression. A 2002 review concluded that there was no evidence that antidepressants reduce the risk of recurrence of depression when their use is terminated. The authors of this review advocated that antidepressants be combined with therapy, and pointed to Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).[27]

Review studies

Recent clinical reviews include:

- A comparison of the relative efficacy of different classes of antidepressants[28] in different settings[29] and in regard to different kinds of depression[30]

- An assessment of antidepressants compared with an "active placebo"[31]

- An assessment of the newer types of the MAOI class[32]

- A meta-analysis of randomized trials of St John's Wort[33]

- A review of the use of antidepressants for childhood depression[34][35]

- A review of all antidepressant trials submitted to the U.S. FDA of 12 anti-depressants, published and unpublished, from 1987 to 2004 was submitted to the FDA in 2004.[5] In the published literature, anti-depressants had 94% success in treating depression.[5] In the withheld literature, they had below 50% success.[5] Combined, all studies showed 51% efficacy[5] - only two points better than that of placebo. This increased the apparent efficacy of different anti-depressants from between 11% to 69% over placebo.[5]

- A meta-analysis by UK, US and Canadian researchers, published in 2008, surveyed all pharmaceutical-company-sponsored drug trials on the six most widely prescribed new-generation antidepressants submitted for approval to the FDA between 1987 and 1999. The results showed, consistent with a prior metaanalysis, that the difference in efficacy between antidepressants and placebo was minimal, but that it increased from virtually no difference at moderate levels of initial depression to a relatively small difference for patients with very severe depression. The difference reached conventional criteria for clinical significance for patients at the upper end of the very severely depressed category, due to a reduction in the efficacy of placebo.[36] The study received widespread media coverage in some countries, but was met with criticism from the professional community.[37] Eli Lilly and Company responded by highlighting that the study did not take into account more recent studies on its product, Prozac, and that it was proud of the difference Prozac has made to millions of people. GlaxoSmithKline warned that this one study should not be used to cause unnecessary alarm and concern for patients. Wyeth pointed out that the data were good enough for FDA approval of the drugs.[38] Two leading UK psychiatrists/pharmacologists, with financial and professional links to pharmaceutical companies, argued that short-term approval trials are not very suitable for evaluating effectiveness, that the unpublished ones are poorer quality, that the meta-analysis authors came from a "psychology background" rather than drug testing background, and that the media and "elements of the medico/scientific community" have "a down on antidepressants" and that the media does not appreciate the seriousness of depression and blames and stigmatizes sufferers in a manner rooted in medieval religious attitudes.[39]

- A May 7, 2002 article in The Washington Post titled "Against Depression, a Sugar Pill Is Hard to Beat" stated, "A new analysis has found that in the majority of trials conducted by drug companies in recent decades, sugar pills have done as well as—or better than—antidepressants. Companies have had to conduct numerous trials to get two that show a positive result, which is the Food and Drug Administration's minimum for approval. What's more, the sugar pills, or placebos, cause profound changes in the same areas of the brain affected by the medicines, according to research published last week... the makers of Prozac had to run five trials to obtain two that were positive, and the makers of Paxil and Zoloft had to run even more... When Leuchter compared the brain changes in patients on placebos, he was amazed to find that many of them had changes in the same parts of the brain that are thought to control important facets of mood... Once the trial was over and the patients who had been given placebos were told as much, they quickly deteriorated. People's belief in the power of antidepressants may explain why they do well on placebos..." [40]

Clinical guidelines

The American Psychiatric Association 2000 Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder [41] indicates that, if preferred by the patient, antidepressant medications may be provided as an initial primary treatment for mild major depressive disorder; antidepressant medications should be provided for moderate to severe major depressive disorder unless electroconvulsive therapy is planned; and a combination of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications or electroconvulsive therapy should be used for psychotic depression. It states that efficacy is generally comparable between classes and within classes and that the initial selection will largely be based on the anticipated side effects for an individual patient, patient preference, quantity and quality of clinical trial data regarding the medication, and its cost.

The UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2004 guidelines indicate that antidepressants should not be used for the initial treatment of mild depression, because the risk-benefit ratio is poor; that for moderate or severe depression an SSRI is more likely to be tolerated than a tricyclic; and that antidepressants for severe depression should be combined with a psychological treatment such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy.[42]

Efficacy limitations and strategies

Between 30% and 50% of individuals treated with a given antidepressant do not show a response.[43][44] Even where there has been a robust response, significant continuing depression and dysfunction is common, with relapse rates 3 to 6 times higher in such cases.[45] In addition, antidepressant drugs tend to lose efficacy over the course of treatment.[46] A number of strategies are used in clinical practice to try to overcome these limits and variations.[47]

"Trial and error" switching

The American Psychiatric Association 2000 Practice Guideline advises that where no response is achieved following six to eight weeks of treatment with an antidepressant, to switch to an antidepressant in the same class, then to a different class of antidepressant.

A 2006 meta-analysis review found wide variation in the findings of prior studies; for patients who had failed to respond to an SSRI antidepressant, between 12% and 86% showed a response to a new drug, with between 5% and 39% ending treatment due to adverse effects. The more antidepressants an individual had already tried, the less likely they were to benefit from a new antidepressant trial.[44] However, a later meta-analysis found no difference between switching to a new drug and staying on the old medication; although 34% of treatment resistant patients responded when switched to the new drug, 40% responded without being switched.[48] Thus, the clinical response to the new drug might be a placebo effect associated with the belief that one is receiving a different medication.

Augmentation and combination

For a partial response, the American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise adding a different kind of pharmaceutical agent to the antidepressant. Studies suggest that most patients fail to achieve remission on a given antidepressant, and augmentation strategies used in clinical practice include the use of lithium and thyroid augmentation, but there is not a good evidence base for these practices or for more novel strategies such as the use of selective dopamine agonists, sex steroids, NRI's, glucocorticoid-specific agents, or the newer anticonvulsants[49]

A combination strategy involves adding one or more additional antidepressants, usually from different classes so as to have a diverse neurochemical effect. Although this may be used in clinical practice, there is little evidence for the relative efficacy or adverse effects of this strategy.[50]

Long-term use

The therapeutic effects of antidepressants typically do not continue once the course of medication ends, resulting in a high rate of relapse. A recent meta-analysis of 31 placebo-controlled antidepressant trials, mostly limited to studies covering a period of one year, found that 18% of patients who had responded to an antidepressant relapsed while still taking it, compared to 41% whose antidepressant was switched for a placebo.[51] The American Psychiatric Association guidelines advise four to five months of continuation treatment on an antidepressant following the resolution of symptoms. For patients with a history of depressive episodes, the British Association for Psychopharmacology's 2000 Guidelines for Treating Depressive Disorders with Antidepressants advise remaining on an antidepressant for at least six months and as long as five years or indefinitely.

Whether or not someone relapses after stopping an antidepressant does not appear to be related to the duration of prior treatment, however, and gradual loss of therapeutic benefit during the course also occurs. A strategy involving the use of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of the acute episode, followed by psychotherapy in its residual phase, has been suggested by some studies.[52][53]

Medication failure

Approximately 30% of patients have remission of depression with medications.[54] For patients with inadequate response, either adding sustained-release bupropion (initially 200 mg per day then increase by 100 mg up to total of 400 mg per day) or buspirone (up to 60 mg per day) for augmentation as a second drug can cause remission in approximately 30% of patients,[55] while switching medications can achieve remission in about 25% of patients.[56]

By pregnancy

There is uncertainty whether pregnancy contributes to medication failure, because the only report so far has drawn much controversy on itself:

In 2006, a widely reported study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) challenged the common assumption that hormonal changes during pregnancy protected expectant mothers against depression, finding that discontinuing anti-depressive medication during pregnancy led to more frequent relapse.[57] The JAMA article did not disclose that several authors had financial ties to pharmaceutical companies making antidepressants. The JAMA later published a correction noting the ties[58] and the authors maintain that the ties have no bearing on their research work. Obstetrician and perinatologist Adam Urato told the Wall Street Journal that patients and medical professionals need advice free of industry influence.[59]

Controversy

Several studies have stimulated doubt about the effectiveness of antidepressants. A 2002 study cited that the difference between antidepressants and placebo is close to negligible.[60]

Through a Freedom of Information Act request, two psychologists obtained 47 studies used by the FDA for approval of the six antidepressants prescribed most widely between 1987-99. Overall, antidepressant pills worked 18% better than placebos, a statistically significant difference, "but not meaningful for people in clinical settings", says psychologist Irving Kirsch, lead author of the study. He and co-author Thomas Moore released their findings in "Prevention and Treatment", an e-journal of the American Psychological Association.[61]

Another study by psychologists at the University of Pennsylvania, Vanderbilt University, the University of Colorado, and the University of New Mexico also found that antidepressant drugs hardly have better effects than a placebo in those cases of mild or moderate depression. The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The study focused on Paxil from GlaxoSmithKline and imipramine.[62]

In 2005, anti-depressants became the most prescribed drug in the United States, causing more debate over the issue. Some doctors believe this is a positive sign that people are finally seeking help for their issues. Others disagree, saying that this shows that people are becoming too dependent on anti-depressants.[63]

Other notable psychiatrists and authors remain skeptical not only about the efficacy of anti-depressants or their overuse, but also about the very principle of prescribing a mind-altering medications to treat something which cannot be objectively proven to be a biological disorder resulting from a chemical imbalance, yet is often presumed to be so. Professor of Psychiatry Thomas Szasz argues mental illness is a social phenomenon rather than a biological disease entity.[64] Harvard-trained psychiatrist Peter Breggin [65] argues that "[anti-depressants] 'work' by causing mental disabilities such as apathy and euphoria that are misinterpreted as improvements" [66][67] Cambridge-educated Bob Johnson, GP, Psychiatrist and author, argues that all psychiatric medications are emotionally damaging due to both the physical effects of the drugs, and because they detract from addressing the root cause of depression, which is to be found, he argues, in the form of unaddressed fears - a product of mind and consciousness, rather than a biological imbalance; and a problem which he argues is more effectively treated by psychological or social interventions than by drug treatment.[68] Meanwhile Joanna Moncrieff, an academic psychiatrist, argues more pragmatically against the effectiveness of anti-depressants in her book 'The Myth of the Chemical Cure.' [69] In his book, 'The Emperor's New Drugs,' psychologist Irving Kirsch argues that the small benefit of antidepressants over placebo might itself be an "enhanced" placebo effect, brought about because patients in clinical trials are able to figure out whether they have been given the drug or the placebo on the basis of side effects.[70] Robert Whitaker, an award-winning journalist, argues in his books, including 'Mad in America,' and 'Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America' which have been highly critical of the profession of psychiatry, that large quantities of evidence about the harm caused by psychotropic drugs including anti-depressants is overlooked and evidence regarding antidepressant efficacy is overstated.[71] These voices critical of the use of anti-depressants are in a minority among psychiatric professionals who generally advocate use of medications according to the evidence base evolved from numerous large drug trials. Some critics, however, argue these drugs trials are subject to bias.[72] More broadly anti-psychiatry and anti-medication perspectives are commonly found in the lay press and especially on the World Wide Web.[73]

Adverse effects

Antidepressants often cause adverse effects, and difficulty tolerating these is the most common reason for discontinuing an effective medication.

Side effects of SSRIs include: nausea, diarrhea, agitation, headaches. Sexual side effects are also common with SSRIs, such as loss of sexual drive, failure to reach orgasm and erectile dysfunction. Serotonin syndrome is also a worrying condition associated with the use of SSRIs. The Food and Drug Administration requires Black Box warnings on all SSRIs, which state that they double suicidal rates (from 2 in 1,000 to 4 in 1,000) in children and adolescents,[74] although it's controversial whether this is due to the medication or as part of the depression itself (i.e. efficacious antidepressant effect can cause those that are severely depressed, to the point of severe psychomotor inhibition, are rendered more alert and thus have increased capacity to carry out suicide even though they are relatively improved in state[75]). The increased risk for suicidality and suicidal behaviour among adults under 25 approaches that seen in children and adolescents.[76]

Side effects of TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants): Fairly common side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, drowsiness, dizziness, tremors, sexual problems, skin rash, and weight gain or loss.

Side effects of MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors): Rare side effects of MAOIs like phenelzine (Nardil) and tranylcypromine (Parnate) include hepatitis, heart attack, stroke, and seizures. Serotonin syndrome is a side effect of MAOIs when combined with certain medications.

General

MAO inhibitors can produce a potentially lethal hypertensive reaction if taken with foods that contain excessively high levels of tyramine, such as mature cheese, cured meats or yeast extracts. Likewise, lethal reactions to both prescription and over the counter medications have occurred. Patients undergoing therapy with MAO inhibiting medications are monitored closely by their prescribing physicians, who are consulted before taking an over the counter or prescribed medication. Such patients must also inform emergency room personnel and keep information with their identification indicating that they are on MAO inhibitors. Some doctors suggest the use of medical identification tags. Although these reactions may be lethal, the total number of deaths due to interactions and dietary concerns is comparable to over-the-counter medications.

Antidepressants are used with care, usually in conjunction with mood stabilisers, in the treatment of bipolar disorder, as they can exacerbate symptoms of mania. They can also trigger mania or hypomania in some patients with bipolar disorder and in a small percentage of patients with depression.[77] SSRIs are the antidepressants most frequently associated with this side effect.

Breast cancer survivors risk having their disease come back if they use certain antidepressants while also taking the cancer prevention drug tamoxifen, according to research released in May 2009.[78]

Anti-depressants are not psychologically addictive in most people, One should never attempt to discontinue psychiatric medication without the knowledge and supervision of a medical practitioner.[79]

Suicide

Patients with depression are at greatest risk for suicide immediately after treatment has begun, as antidepressants can reduce the symptoms of depression such as psychomotor retardation or lack of motivation before mood starts to improve.[citation needed] Although this appears paradoxical, studies[which?] indicate that suicidal ideation is a relatively common[weasel words] at the start of antidepressant therapy, and it may be especially common in younger patients such as pre-adolescents and teenagers. Manufacturers and physicians often recommend that other family members and loved ones monitor the young patient's behavior for any signs of suicidal ideation or behaviors, especially in the first eight weeks of therapy.

Until the black box warnings on these drugs were issued by FDA and equivalent agencies in other nations, side effects and alerting families to risk were largely ignored and downplayed by manufacturers and practitioners. This may have resulted in some deaths by suicide although direct proof for such a link is largely anecdotal.[original research?] The higher incidence of suicide ideation reported in a number of studies has drawn attention and caution in how these drugs are used.

People under the age of 24 who suffer from depression are warned that the use of antidepressants could increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Federal health officials unveiled proposed changes to the labels on antidepressant drugs in December 2006 to warn people of this danger.

The FDA states that Paxil should be avoided in children and teens and that in cases of pediatric cases of depressive disorder the antidepressant drug to be used is Prozac.[80]

On September 6, 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the suicide rate in American adolescents, (especially girls, 10 to 24 years old), increased 8% (2003 to 2004), the largest jump in 15 years,[81] to 4,599 suicides in Americans ages 10 to 24 in 2004, from 4,232 in 2003, giving a suicide rate of 7.32 per 100,000 people that age. The rate previously dropped to 6.78 per 100,000 in 2003 from 9.48 per 100,000 in 1990.

Psychiatrists[who?] found that the increase is due to the decline in prescriptions of antidepressant drugs like Prozac to young people since 2003, leaving more cases of serious depression untreated. A December 2006 study found that a decrease in antidepressant prescriptions to minors of just a few percentage points coincided with a 14% increase in suicides in the United States; in the Netherlands, the suicide rate was 50% up after a fall in antidepressant prescriptions.[82]

Jon Jureidini, a critic of this study, says that the US "2004 suicide figures were compared simplistically with the previous year, rather than examining the change in trends over several years".[83] The pitfalls of such attempts to infer a trend using just two data points (years 2003 and 2004) are further demonstrated by the fact that, according to the new epidemiological data, the suicide rate in 2005 in children and adolescents actually declined despite the continuing decrease of SSRI prescriptions. "It is risky to draw conclusions from limited ecologic analyses of isolated year-to-year fluctuations in antidepressant prescriptions and suicides.

One promising epidemiological approach involves examining the associations between trends in psychotropic medication use and suicide over time across a large number of small geographic regions. Until the results of more detailed analyses are known, prudence dictates deferring judgment concerning the public health effects of the FDA warnings."[84][85] Subsequest follow-up studies have supported the hypothesis that antidepressant drugs reduce suicide risk.[86][87] However, the conclusion that societal suicide rate decreases are due to antidepressant prescription is unsupported given the plethora of confounding variables.[original research?]

Another study was taken and the overall rate of suicidal acts was 27 per 1000 person-years, and most events occurred within 6 months of medication initiation. According to this study, no commonly used antidepressant medication has an advantage in regard to suicide-related safety. It remains a question as to whether other therapeutic maneuvers, such as ongoing counseling, provide a protective counter-effect to children's and adolescents' antidepressant-associated risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviour.[88]

Sexual

Sexual dysfunction is a very common side effect, especially with SSRIs. Common sexual side effects include problems with sexual desire, lack of interest in sex, and anorgasmia (trouble achieving orgasm).[89] Although usually reversible, these sexual side effects can, in rare cases, last for months or years after the drug has been completely withdrawn. This is known as Post SSRI Sexual Dysfunction.

SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction affects 30% to 50% or more of individuals who take these drugs for depression.[citation needed] Biochemical mechanisms suggested as causative include increased serotonin, particularly affecting 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors; decreased dopamine; decreased norepinephrine; blockade of cholinergic and α1 adrenergic receptors; inhibition of nitric oxide synthetase; and elevation of prolactin levels.[90]

Bupropion, a dual reuptake inhibitor (NE and DA), often causes a moderate increase in sexual drive, due to increased dopamine activity. This effect is also seen with dopamine reuptake inhibitors, CNS stimulants and dopamine agonists, and is due to increases in testosterone production (due to inhibition of prolactin) and nitric oxide synthesis. Mirtazapine (Remeron) is reported to have fewer sexual side effects, most likely because it antagonizes 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors. Mirtazapine can in some cases reverse sexual dysfunction induced by SSRIs, which is also likely due to its antagonisation of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors [91]

Apomorphine, nefazodone, and nitroglycerin have been shown to reverse some sexual dysfunction via increased nitric oxide activity. MAOIs are reported to have fewer negative effects on sexual function and sexual drive, particularly moclobemide at a 1.9% rate of occurrence. Bethanechol has been reported to reverse MAOI-induced sexual dysfunction via its cholinergic agonist properties.[92]

Love

Dr. Helen Fisher, an anthropologist from Rutgers University, has theorized that based on the proposed actions of certain neurotransmitters, SSRIs may alter the perception of some emotions related to love such as desire and arousal. "There’s every reason to think SSRIs blunt your ability to fall and stay in love," said Helen Fisher. During sex, a cocktail of hormones is released that appears to play important roles in fostering romantic attachment within the brain. Take away sex, and romantic love can dwindle. But this is just part of the problem, say Fisher and University of Virginia psychiatrist James Thomson.

Dopamine also appears central to the neurobiology of romantic love and attachment, conditions that Fisher believes to be affected by — but ultimately distinct from — sexual love and its effects. She and Thomson say that SSRIs may do more than cause sexual dysfunction: They also suppress romance.

"There are all sorts of unconscious systems in our brain that we use to negotiate romantic love and romantic attraction," said Thomson. "If these drugs cause conscious sexual side effects, we’d argue that there are going to be side effects that are not conscious."

A psychological study showed a small effect to back up this hypothesis but the study has not been reproduced and no clinical evidence exists to lend support to this theory. [93]

Thymoanesthesia

Closely related to sexual side effects is the phenomenon of emotional blunting, or mood anesthesia. Many users of SSRIs complain of apathy, lack of motivation, emotional numbness, feelings of detachment, and indifference to surroundings. They may describe this as a feeling of "not caring about anything anymore." All SSRIs, SNRIs, and serotonergic TCAs can cause this to varying degrees, especially at high doses.[94]

REM Sleep

All major antidepressant drugs, except trimipramine, mirtazapine and nefazodone suppress REM sleep, and it has been proposed that the clinical efficacy of these drugs largely derives from their suppressant effects on REM sleep. The three major classes of antidepressant drugs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), profoundly suppress REM sleep.[95] Mirtazapine either has no effect on REM sleep or increases it slightly.[96] The MAOIs almost completely suppress REM sleep, while the TCAs and SSRIs have been shown to produce immediate (40-85%) and sustained (30-50%) reductions in REM sleep. This effect often causes increased fatigue in patients who take large doses of antidepressants for extended periods of time. Such fatigue can occasionally interfere with a patient's everyday activities. Abrupt discontinuation of MAOIs can cause a temporary phenomenon known as "REM rebound" in which the patient experiences extremely vivid dreams and nightmares.

Weight gain

Many antidepressants are associated with weight gain usually in the range of 5–25 kg (11–55 lb) but rarely upwards of 50 kg (110 lb). The specific cause is unknown, but antidepressants are associated with increased cravings, an inability to feel full despite consuming enough calories, low energy levels and increased daytime sleepiness, which can lead to overeating and a lack of desire to exercise, and dry mouth, which can lead to ingestion of calorie-laden beverages. The antihistaminic properties of certain TCA and TeCA class antidepressants have been shown to contribute to the common side effects of increased appetite and weight gain associated with these classes of medication. Eating low fat, low protein carbohydrate snacks and carbohydrate-rich dinners allows the brain to make serotonin which then controls appetite and balances mood. Carbohydrates thus eaten, as part of a balanced diet, by virtue of their effect on brain serotonin levels, can support weight loss in the setting of antidepressant weight gain.[97][98]

Withdrawal symptoms

If an SSRI medication is suddenly discontinued, it may produce both somatic and psychological withdrawal symptoms, a phenomenon known as "SSRI discontinuation syndrome" (Tamam & Ozpoyraz, 2002). When the decision is made to stop taking antidepressants it is common practice to "wean" off of them by slowly decreasing the dose over a period of several weeks. Most cases of discontinuation syndrome last between one and four weeks.[citation needed]

The selection of an antidepressant and dosage suitable for a certain case and a certain person is a lengthy and complicated process, requiring the knowledge of a professional. Certain antidepressants can initially make depression worse, can induce anxiety, or can make a patient aggressive, dysphoric or acutely suicidal.[citation needed] In rare cases, an antidepressant can induce a switch from depression to mania or hypomania.[citation needed]

Mechanisms of action

The therapeutic effects of antidepressants are believed to be caused by their effects on neurotransmitters and neurotransmission.

The Monoamine Hypothesis is a biological theory stating that depression is caused by the underactivity in the brain of monoamines, such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. In the 1950s the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants were accidentally discovered to be effective in the treatment of depression. These findings and other supporting evidence led Joseph Schildkraut to publish his paper called "The Catecholamine Hypothesis of Affective Disorders" in 1965. Schildkraut associated low levels of neurotransmitters with depression. Research into other mental impairments such as schizophrenia also found that too little activity of certain neurotransmitters were connected to these disorders. The hypothesis has been a major focus of research in the fields pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy for over 25 years.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) block the degradation of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine by inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase, leading to increased concentrations of these neurotransmitters in the brain and an increase in neurotransmission.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) prevent the reuptake of various neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and to a much less extent, dopamine. Nowadays the most common antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which prevent the reuptake of serotonin (thereby increasing the level of active serotonin in synapses of the brain). Other novel antidepressants affect norepinephrine reuptake, or different receptors on the nerve cell.

While MAOIs, TCAs and SSRIs increase serotonin levels, others prevent serotonin from binding to 5-HT2A receptors, suggesting it is too simplistic to say serotonin is a happy hormone. In fact, when the former antidepressants build up in the bloodstream and the serotonin level is increased, it is common for the patient to feel worse for the first weeks of treatment. One explanation of this is that 5-HT2A receptors evolved as a saturation signal (people who use 5-HT2A antagonists often gain weight), telling the animal to stop searching for food, a mate, etc., and to start looking for predators. In a threatening situation it is beneficial for the animal not to feel hungry even if it needs to eat. Stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors will achieve that. But if the threat is long lasting the animal needs to start eating and mating again - the fact that it survived shows that the threat was not so dangerous as the animal felt. So the number of 5-HT2A receptors decreases through a process known as downregulation and the animal goes back to its normal behavior. This suggests that there are two ways to relieve anxiety in humans with serotonergic drugs: by blocking stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors or by overstimulating them until they decrease via tolerance.

The stimulation or blocking of different receptors on a cell affects its genetic expression. Recent findings have shown that neurogenesis, and thus, changes in brain morphogenesis, mediate the effects of antidepressant drugs.[99]

Another hypothesis is that antidepressants may have some longer-term effects due to the promotion of neurogenesis in the hippocampus, an effect found in mice.[100][101] Other animal research suggests that antidepressants can affect the expression of genes in brain cells, by influencing "clock genes". [102]

Other research suggests that delayed onset of clinical effects from antidepressants indicates involvement of adaptive changes in antidepressant effects. Rodent studies have consistently shown upregulation of the 3, 5-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) system induced by different types of chronic but not acute antidepressant treatment, including serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium and electroconvulsions. cAMP is synthesized from adenosine 5-triphosphate (ATP) by adenylyl cyclase and metabolized by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs).[103] Data also suggest that antidepressants can modulate neural plasticity in long-term administration.[104]

One theory regarding the cause of depression is that it is characterized by an overactive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) that resembles the neuro-endocrine (cortisol) response to stress. These HPA axis abnormalities participate in the development of depressive symptoms, and antidepressants serve to regulate HPA axis function.[105]

Comparison

A number of antidepressants have been compared below:[106][107][108][109]

Compound SERT NET DAT H1 M1-5 α1 α2 5-HT1A 5-HT2 D2 Agomelatine ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 270 ? Amitriptyline 4.3 35 3250 0.95 9.6 24 690 450 18 1460 Amoxapine 58 16 4310 25 1000 50 2600 ? ? ? Atomoxetine 8.9 2.03 1080 5500 2060 3800 8800 10900 940 35000+ Bupropion 45026 1389 2784 11800 35000+ 4200 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ Buspirone ? ? ? ? ? 138 ? 5.7 174 362 Butriptyline 1360 5100 3940 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Citalopram 1.16 4070 28100 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Clomipramine 0.28 38 2190 31 37 38 3200 ? ? ? Desipramine 17.6 0.83 3190 60 66 100 5500 6400 350 3500 Dosulepin 8.6 46 5310 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Doxepin 68 29.5 12100 0.17 23 23.5 1270 276 27 360 Duloxetine 0.8 7.5 240 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Etoperidone 890 20000 52000 3100 35000+ 38 570 85 36 2300 Femoxetine 11 760 2050 4200 184 650 1970 2285 130 590 Fluoxetine 0.81 240 3600 5400 590 3800 13900 32400 280 12000 Fluvoxamine 0.81 240 3600 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Imipramine 1.4 37 8500 37 46 32 3100 5800 150 620 Lofepramine 70 5.4 18000 360 67 100 2700 4600 200 2000 Maprotiline 5800 11.1 1000 2 570 90 9400 ? ? ? Mazindol 100 1.4 11 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Mianserin 4000 71 9400 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Milnacipran 123 200 10000+ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Mirtazapine 1500+ 1250~ 1500+ 1~ 1000~ 500~ 100~ 1500+ 10~ 1500+ Nefazodone 200 360 360 24000 11000 48 640 80 26 910 Nisoxetine 383 5.1 477 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Nomifensine 1010 15.6 56 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Nortriptyline 18 4.37 1140 6.3 37 55 2030 294 41 2570 Oxaprotiline 3900 4.9 4340 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Paroxetine 0.13 40 490 22000 108 4600 17000 35000+ 19000 32000 Protriptyline 19.6 1.41 2100 25 25 130 6600 ? ? ? Reboxetine 720 11 10000+ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Sertraline 0.29 420 25 24000 630 380 4100 35000+ 9900 10700 Trazodone 160 8500 7400 1100 35000+ 42 320 96 25.0 35000+ Trimipramine 149 2450 3780 0.27 58 24 680 ? ? ? Venlafaxine 82 2480 7647 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ 35000+ Viloxazine 17300 155 100000+ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Zimelidine 152 9400 11700 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? The values above are expressed as equilibrium dissociation constants. It should be noted that smaller dissociation constant indicates more efficacy. SERT, NET, and DAT correspond to the abilities of the compounds to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, respectively. The other values correspond to their affinity for various receptors.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulation

Recent studies show pro-inflammatory cytokine processes take place during clinical depression, mania and bipolar disorder, and it is possible that symptoms of these conditions are attenuated by the pharmacological effect of antidepressants on the immune system.[110][111][112][113][114]

Studies also show that the chronic secretion of stress hormones as a result of disease, including somatic infections or autoimmune syndromes, may reduce the effect of neurotransmitters or other receptors in the brain by cell-mediated pro-inflammatory pathways, thereby leading to the dysregulation of neurohormones.[113] SSRIs, SNRIs and tricyclic antidepressants acting on serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine receptors have been shown to be immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory against pro-inflammatory cytokine processes, specifically on the regulation of Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10), as well as TNF-alpha and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). Antidepressants have also been shown to suppress TH1 upregulation.[115][116][117][118][119]

Antidepressants, specifically TCAs and SNRIs (or SSRI-NRI combinations), have also shown analgesic properties.[120][121]

These studies warrant investigation for antidepressants for use in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric illness and that a psycho-neuroimmunological approach may be required for optimal pharmacotherapy.[122] Future antidepressants may be made to specifically target the immune system by either blocking the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines or increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[123]

History

Various opiates (via the µ-opioid receptor and κ-opioid receptor) and amphetamines were commonly used as antidepressants until the mid-1950s, when they fell out of favor due to their addictive nature and side effects.[124] Extracts from the herb St John's Wort have long been used (as a "nerve tonic") to alleviate depression.[125]

Isoniazid and iproniazid

In 1951, two people from Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, Irving Selikoff and Edward Robitzek, began clinical trials on two new anti-tuberculosis agents from Hoffman-LaRoche, isoniazid and iproniazid. Only patients with a poor prognosis were initially treated; nevertheless, their condition improved dramatically. Selikoff and Robitzek noted "a subtle general stimulation . . . the patients exhibited renewed vigor and indeed this occasionally served to introduce disciplinary problems."[126] The promise of a cure for tuberculosis in the Sea View Hospital trials was excitedly discussed in the mainstream press. In 1952, learning of the stimulating side effects of isoniazid, the Cincinnati psychiatrist Max Lurie tried it on his patients. In the following year, he and Harry Salzer reported that isoniazid improved depression in two thirds of their patients and coined the term antidepressant to describe its action.[127] A similar incident took place in Paris, where Jean Delay, head of psychiatry at Sainte-Anne Hospital, found out from his pulmonology colleagues at Cochin Hospital about the side effects of isoniazid. In 1952, before Lurie and Salzer, Delay, with the resident Jean-Francois Buisson, reported the positive effect of isoniazid on depressed patients.[128] For reasons unrelated to its efficacy, isoniazid as an antidepressant was soon overshadowed by the more toxic iproniazid,[127] although it remains a mainstay of tuberculosis treatment. The mode of antidepressant action of isoniazid is still unclear. It is speculated that its effect is due to the inhibition of diamine oxidase, coupled with a weak inhibition of monoamine oxidase A.[129]

Another anti-tuberculosis drug tried at the same time by Selikoff and Robitzek, iproniazid, showed a greater "psychostimulant" effect, but more pronounced toxicity.[130] After the publications on isoniazid, papers by Jackson Smith, Gordon Kamman, George Crane, and Frank Ayd appeared, describing the psychiatric applications of iproniazid. Ernst Zeller found iproniazid to be a potent monoamine oxidase inhibitor.[131] Nevertheless, iproniazid remained relatively obscure until Nathan Kline, the influential and flamboyant head of research at Rockland State Hospital, began to popularize it in the medical and popular press as a "psychic energizer".[131][132] Roche put a significant marketing effort behind iproniazid, including promoting its off-label use for depression.[131] Its sales grew massively in the following years, until it was recalled from the market in 1961 due to cases of lethal hepatotoxicity.[131]

Imipramine

The discovery that a tricyclic ("three ringed") compound had a significant antidepressant effect was first made in 1957 by Roland Kuhn in a Swiss psychiatric hospital. By that time antihistamine derivatives were increasingly used to treat surgical shock and then as psychiatric neuroleptics. Although in 1955 reserpine was shown to be more effective than placebo in alleviating anxious depression, neuroleptics (literally, "to seize the nerves" or "to take hold of nerves") were being developed as sedatives and antipsychotics.

Attempting to improve the effectiveness of chlorpromazine, Kuhn, in conjunction with the Geigy pharmaceutical company, discovered that compound "G 22355" (manufactured and patented in the US in 1951 by Häfliger and Schinder) had a beneficial effect in patients with depression accompanied by mental and motor retardation.[133] Kuhn first reported his findings on what he called a "thymoleptic" (literally, "taking hold of the emotions," in contrast with neuroleptics, "taking hold of the nerves") in 1955-56. These gradually became established, resulting in marketing of the first tricyclic antidepressant, imipramine, soon followed by variants.

Later history

These new drug therapies became prescription drugs in the 1950s. It was estimated that no more than 50 to 100 people per million suffered from the kind of depression that these new drugs would treat, and pharmaceutical companies were not enthusiastic. Sales through the 1960s remained poor compared to the major tranquilizers (neuroleptics/antipsychotics) and minor tranquilizers (such as benzodiazepines), which were being marketed for different uses.[134] Imipramine remained in common use and numerous successors were introduced. The field of MAO inhibitors remained quiet for many years until "reversible" forms affecting only the MAO-A subtype were introduced, avoiding some of the adverse effects.[134][135]

Most pharmacologists by the 1960s thought the main therapeutic action of tricyclics was to inhibit norepinephrine reuptake, but it was gradually observed that this action was associated with energizing and motor stimulating effects, while some antidepressant compounds appeared to have differing effects through action on serotonin systems (notably proposed in 1969 by Carlsson and Lindqvist as well as Lapin and Oxenkrug).

Researchers began a process of rational drug design to isolate antihistamine-derived compounds that would selectively target these systems. The first such compound to be patented was zimelidine in 1971, while the first released clinically was indalpine. Fluoxetine was approved for commercial use by the Food and Drug Administration (United States) in 1988, becoming the first blockbuster SSRI. Fluoxetine was developed at Eli Lilly and Company in the early 1970s by Bryan Molloy, David Wong and others.[136][137]

While it had fallen out of favor in most countries through the 19th and 20th centuries, the herb St John's Wort became increasingly popular in Germany, where Hypericum extracts were eventually licensed, packaged and prescribed by doctors. Small-scale efficacy trials were carried out in the 1970s and 1980s, and attention grew in the 1990s following a meta-analysis of these.[138] It remained an over-the-counter drug (OTC) or supplement in most countries and research continued to investigate its neurotransmitter effects and active components, particularly hyperforin[139][140]

SSRIs became known as "novel antidepressants" along with other newer drugs such as SNRIs and NRIs with various selective effects, such as venlafaxine, duloxetine, nefazodone and mirtazapine.[141]

Society and culture

Prescription trends

In the United Kingdom the use of antidepressants increased by 234% in the 10 years up to 2002.[142] In the United States a 2005 independent report stated that 11% of women and 5% of men in the non-institutionalized population (2002) take antidepressants[143] A 1998 survey found that 67% of patients diagnosed with depression were prescribed an antidepressant.[144] A 2007 study suggested that 25% of Americans were overdiagnosed with depression, regardless of any medical intervention.[145] The findings were based on a national survey of 8,098 people.

A 2002 survey found that about 3.5% of all people in France were being prescribed antidepressants, compared to 1.7% in 1992, often for conditions other than depression and often not in line with authorizations or guidelines[146] Between 1996 and 2004 in British Columbia, antidepressant use increased from 3.4% to 7.2% of the population.[147] Data from 1992 to 2001 from the Netherlands indicated an increasing rate of prescriptions of SSRIs, and an increasing duration of treatment.[148] Surveys indicate that antidepressant use, particularly of SSRIs, has increased rapidly in most developed countries, driven by an increased awareness of depression together with the availability and commercial promotion of new antidepressants.[149] Antidepressants are also increasingly used worldwide for non-depressive patients as studies continue to show the potential of immunomodulatory, analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties in antidepressants.

The choice of particular antidepressant is reported to be based, in the absence of research evidence of differences in efficacy, on seeking to avoid certain side effects, and taking into account comorbid (co-occurring) psychiatric disorders, specific clinical symptoms and prior treatment history.[150]

It is also reported that, despite equivocal evidence of a significant difference in efficacy between older and newer antidepressants, clinicians perceive the newer drugs, including SSRIs and SNRIs, to be more effective than the older drugs (tricyclics and MAOIs).[151] A survey in the UK found that male general physicians were more likely to prescribe antidepressants than female doctors.[152]

The number of antidepressants prescribed by the NHS in the United Kingdom almost doubled during one decade, authorities reported in 2010. Furthermore the number highly increased in 2009 when 39.1 million prescriptions were issued compared with 20.1 million issued in 1999. Also, physicians issued 3.18 million more prescriptions in 2009 than in 2008. Health authorities believed the increase was partly linked to the recession. However, other reasons include a diagnosis improvement, a reduction of the stigma on mental ill-health, and more distress caused by the economic crisis. Furthermore, physicians concern is that some people who exhibit milder symptoms of depression are being prescribed drugs unnecessarily due to the lack of other options including talking therapies, counseling and cognitive behavior therapy. One more factor that may be increasing the consumption of antidepressants is the fact that these medications now are used for other conditions including social anxiety and post traumatic stress.[153]

The use of antidepressants in the United States doubled over one decade, from 1996 to 2005. Antidepressant drugs were prescribed to 13 million in 1996 and to 27 million people by 2005. In 2008, more than 164 million prescriptions were written. During this period, patients were less likely to undergo psychotherapy.[154]

Most commonly prescribed

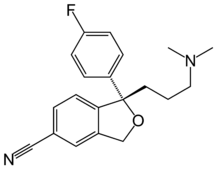

Structural formula of the SSRI escitalopram, in its free base form.

Structural formula of the SSRI escitalopram, in its free base form.

United States: The most commonly prescribed antidepressants in the US retail market in 2010 [155] were:

Drug Brand Class 2010 Prescriptions Sertraline Zoloft SSRI 33,409,838 Escitalopram Lexapro SSRI 23,000,456 Fluoxetine SSRI 24,473,994 Bupropion SR NDRI 4,588,996 Bupropion ER NDRI 3,132,327 Bupropion XL NDRI 7,317,814 Paroxetine SSRI 12,979,366 Bupropion Wellbutrin XL NDRI 753,516 Venlafaxine Effexor XR SNRI 7,603,949 Venlafaxine ER SNRI 5,526,132 Citalopram Celexa SSRI 27,993,635 Trazodone SARI 18,786,495 Amitriptyline TCA 12,611,254 Duloxetine Cymbalta SNRI 14,591,949 Mirtazapine TeCA 6,308,288 Nortriptyline TCA 3,210,476 Desvenlafaxine Pristiq SNRI 3,412,354 Germany: The most commonly prescribed antidepressant in Germany is reported to be (concentrated extracts of) hypericum perforatum (St John's Wort).[156]

Netherlands: In the Netherlands, paroxetine, marketed as Seroxat among generic preparations, is the most prescribed antidepressant, followed by the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, citalopram and venlafaxine.[157]

Lawsuits

In many cases SSRI drug manufacturers have withheld information from the FDA and the public to play down the risks and adverse effects associated with SSRIs. This had led to litigation against many of the pharmaceutical manufacturers of SSRI anti-depressants in cases covering suicidality, SSRI withdrawal and birth defects in neonates from nursing mothers on SSRIs.

In one of the only three cases to ever go to trial for SSRI indication in suicide, Eli Lilly and Company was caught corrupting the judicial process by making a deal with the plaintiff's attorney to throw the case, in part by not disclosing damaging evidence to the jury. The case, known as the Fentress Case involved a Kentucky man, Joseph Wesbecker, on Prozac, who went to his workplace and opened fire with an assault rifle killing 8 people (including Fentress), and injuring 12 others before turning the gun on himself. The jury returned a 9-to-3 verdict in favor of Lilly. The judge, in the end, took the matter to the Kentucky Supreme Court, which found that "there was a serious lack of candor with the trial court and there may have been deception, bad faith conduct, abuse of judicial process and, perhaps even fraud." The judge later revoked the verdict and instead, recorded the case as settled. The value of the secret settlement deal has never been disclosed, but was reportedly "tremendous".[158]

On December 22, 2006, a US court decided in Hoorman, et al. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. that individuals who purchased Paxil or Paxil CR (paroxetine) for a minor child may be eligible for benefits under a $63.8 million Proposed Settlement. The lawsuit won the claim that pharmaceutical maker GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) promoted Paxil or Paxil CR for prescription to children and adolescents while withholding and concealing material information about the medication's safety and effectiveness for minors.[159]

The lawsuit stemmed from a consumer advocate protest against Paroxetine manufacturer GSK. Since the FDA approved paroxetine in 1992, approximately 5,000 U.S. citizens – and thousands more worldwide[who?] – have sued GSK[citation needed]. Most of these people feel they were not sufficiently warned in advance of the drug's side effects and addictive properties.

According to the Paxil Protest website, hundreds more lawsuits have been filed against GSK. The Paxil Protest website was launched August 8, 2005 to offer both information about the protest and information on Paxil previously unavailable to the public. Just three weeks after its launch, the site received more than a quarter of a million hits.

The original Paxil Protest website is no longer available. It is understood that the action to remove the site from the internet was undertaken as part of a confidentiality agreement or 'gagging order' which the owner of the site entered into as part of a settlement of his action against GlaxoSmithKline. (However, in March 2007, the website Seroxat Secrets[160] discovered that an archive of Paxil Protest site[161] was still available on the internet via Archive.org) Gagging orders are common in such cases and can extend to documents that defendants wish to remain hidden from the public. However, in some cases, such documents can become public at a later date, such as those made public by Peter Breggin in February 2006. A press release from Dr. Breggin can be seen here:[162]

In January 2007, according to the Seroxat Secrets website,[163] the national group litigation in the United Kingdom, on behalf of several hundred people who allege withdrawal reactions after use of the drug Seroxat, against GlaxoSmithKline plc, moved a step closer to the High Court in London, with the confirmation that Public Funding had been reinstated following a decision by the Public Interest Appeal Panel. The issue at the heart of this particular action claims Seroxat is a defective drug in that it has a propensity to cause a withdrawal reaction. Hugh James Solicitors confirm this news on their website[164]

On January 29, 2007, the BBC in the UK aired a fourth documentary in its 'Panorama'[165] series about the controversial drug Seroxat. This programme, entitled Secrets of the Drug Trials, focuses on three GSK paediatric clinical trials on depressed children and adolescents.

See also

- Antidepressants in Japan

- Depression and natural therapies

References

- ^ Bodkin JA. et al., Zornberg Gwen L., Lukas Scott E., Cole Jonathan O. (1995). "Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 15 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1097/00004714-199502000-00008. PMID 7714228.

- ^ Wheeler Vega JA, Mortimer AM, Tyson PJ (May 2003). "Conventional antipsychotic prescription in unipolar depression, I: an audit and recommendations for practice". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64 (5): 568–74. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0512. PMID 12755661. http://www.psychiatrist.com/abstracts/abstracts.asp?abstract=200305/050311.htm.

- ^ Petty F, Trivedi MH, Fulton M, Rush AJ (November 1995). "Benzodiazepines as antidepressants: does GABA play a role in depression?". Biological Psychiatry 38 (9): 578–91. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(95)00049-7. PMID 8573660.

- ^ "Do Antidepressants Work as Promised?

- ^ a b c d e f g h Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R (January 2008). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (3): 252–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779. PMID 18199864.

- ^ Schreiber S, Bleich A, Pick CG. (Feb-April 2002). "Venlafaxine and mirtazapine: different mechanisms of antidepressant action, common opioid-mediated antinociceptive effects--a possible opioid involvement in severe depression?". J Molecular Neuroscience 18 (1–2): 143–9. doi:10.1385/JMN:18:1-2:143. PMID 11931344.

- ^ Lacasse J, Leo J (2005). "Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature". PLoS Med 2 (12): e392. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392. PMC 1277931. PMID 16268734. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1277931. Full text

- ^ Uz T, Ahmed R, Akhisaroglu M, Kurtuncu M, Imbesi M, Dirim Arslan A, Manev H (2005). "Effect of fluoxetine and cocaine on the expression of clock genes in the mouse hippocampus and striatum". Neuroscience 134 (4): 1309–16. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.003. PMID 15994025.

- ^ Yuferov V, Butelman E, Kreek M (2005). "Biological clock: biological clocks may modulate drug addiction". Eur J Hum Genet 13 (10): 1101–3. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201483. PMID 16094306.

- ^ Manev H, Uz T (2006). "Clock genes as a link between addiction and obesity". Eur J Hum Genet 14 (1): 5. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201524. PMID 16288309.

- ^ Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Geddes JR, Bhagwagar Z (2005). "Early Onset of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressant Action: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Arch Gen Psychiatry 63 (11): 1217–23. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1217. PMC 2211759. PMID 17088502. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2211759.

- ^ http://www.cnsforum.com/imagebank/item/Drug_nassa/default.aspx

- ^ Stimmel, GL; Dopheide, JA; Stahl, SM (Jan-Feb 1997). "Mirtazapine: an antidepressant with noradrenergic and specific serotonergic effects". Pharmacotherapy (American College of Clinical Pharmacy) 17 (1): 10–21. ISSN 0277-0008. PMID 9017762.

- ^ Stahl, SM; Pradko, JF; Haight, BR; Modell, JG; Rockett, CB; Learned-Coughlin, S (2004). "A Review of the Neuropharmacology of Bupropion, a Dual Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry (Physicians Postgraduate Press) 6 (4): 159–166. doi:10.4088/PCC.v06n0403. PMC 514842. PMID 15361919. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=514842.

- ^ doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2007.08.009

- ^ Cascade EF, Kalali AH (June 2007). "EMSAM: The First Year". Psychiatry 2007. http://www.psychiatrymmc.com/emsam-the-first-year/. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ Merck Manual: Depressive Disorders

- ^ Psychostimulants in the Treatment of Depression: A Review of the Evidence CNS Drugs, Volume 21, Number 3, 2007 , pp. 239-257(19)

- ^ Akhondzadeh, S.; Fallah-Pour, H.; Afkham, K.; Jamshidi, A. H.; Khalighi-Cigaroudi, F. (2004). "Comparison of Crocus sativus L. And imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: A pilot double-blind randomized trial ISRCTN45683816". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 4: 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-4-12. PMC 517724. PMID 15341662. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=517724.

- ^ Akhondzadehbasti, A; Moshiri, E; Noorbala, A; Jamshidi, A; Abbasi, S; Akhondzadeh, S (2007). "Comparison of petal of Crocus sativus L. and fluoxetine in the treatment of depressed outpatients: A pilot double-blind randomized trial". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 31 (2): 439–42. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.11.010. PMID 17174460.

- ^ Herreraruiz, M; Garciabeltran, Y; Mora, S; Diazveliz, G; Viana, G; Tortoriello, J; Ramirez, G (2006). "Antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of hydroalcoholic extract from Salvia elegans☆". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 107 (1): 53–8. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.003. PMID 16530995.

- ^ Seol, Geun Hee; Shim, Hyun Soo; Kim, Pill-Joo; Moon, Hea Kyung; Lee, Ki Ho; Shim, Insop; Suh, Suk Hyo; Min, Sun Seek (2010). "Antidepressant-like effect of Salvia sclarea is explained by modulation of dopamine activities in rats". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 130 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.035. PMID 20441789.

- ^ Boult, C; Krinke, UB; Urdangarin, CF; Skarin, V (1999). "The validity of nutritional status as a marker for future disability and depressive symptoms among high-risk older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47 (8): 995–9. PMID 10443862.

- ^ Nemets, H.; Nemets, B.; Apter, A.; Bracha, Z.; Belmaker, R. H. (2006). "Omega-3 Treatment of Childhood Depression: A Controlled, Double-Blind Pilot Study". American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (6): 1098–1100. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1098. PMID 16741212.

- ^ Sontrop, J; Campbell, M (2006). "ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and depression: A review of the evidence and a methodological critique". Preventive Medicine 42 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.005. PMID 16337677.

- ^ Rocha Araujo, D. M.; Vilarim, M. M.; Nardi, A. E. (2010). "What is the effectiveness of the use of polyunsaturated fatty acid omega-3 in the treatment of depression?". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 10 (7): 1117–1129. doi:10.1586/ern.10.77. PMID 20586692.

- ^ Hollon SD, Thase ME, Markowitz JC. "Treatment and prevention of depression", Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2002;3:1–39.