- Saffron

-

For other uses, see Saffron (disambiguation).

Saffron crocus

C. sativus blossom with crimson stigmas. Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae Division: Spermatophytae Subdivision: Angiospermae (unranked): Liliopsidae Order: Asparagales Family: Iridaceae Subfamily: Crocoideae Genus: Crocus Species: C. sativus Binomial name Crocus sativus

L.Saffron (pronounced

/ˈsæfrɒn/) is a spice derived from the flower of Crocus sativus, commonly known as the saffron crocus. Crocus is a genus in the family Iridaceae. Each saffron crocus grows to 20–30 cm (8–12 in) and bears up to four flowers, each with three vivid crimson stigmas, which are each the distal end of a carpel.[1] Together with the styles, or stalks that connect the stigmas to their host plant, the dried stigmas are used mainly in various cuisines as a seasoning and colouring agent. Saffron, long among the world's most costly spices by weight,[2][3] is native to Southwest Asia[4][3] and was first cultivated in Greece.[5] As a genetically monomorphic clone,[6] it was slowly propagated throughout much of Eurasia and was later brought to parts of North Africa, North America, and Oceania.

/ˈsæfrɒn/) is a spice derived from the flower of Crocus sativus, commonly known as the saffron crocus. Crocus is a genus in the family Iridaceae. Each saffron crocus grows to 20–30 cm (8–12 in) and bears up to four flowers, each with three vivid crimson stigmas, which are each the distal end of a carpel.[1] Together with the styles, or stalks that connect the stigmas to their host plant, the dried stigmas are used mainly in various cuisines as a seasoning and colouring agent. Saffron, long among the world's most costly spices by weight,[2][3] is native to Southwest Asia[4][3] and was first cultivated in Greece.[5] As a genetically monomorphic clone,[6] it was slowly propagated throughout much of Eurasia and was later brought to parts of North Africa, North America, and Oceania.The saffron crocus, unknown in the wild, likely descends from Crocus cartwrightianus, which originated in Crete or Central Asia;[6] C. thomasii and C. pallasii are other possible precursors.[7][8] The saffron crocus is a triploid that is "self-incompatible" and male sterile; it undergoes aberrant meiosis and is hence incapable of independent sexual reproduction—all propagation is by vegetative multiplication via manual "divide-and-set" of a starter clone or by interspecific hybridisation.[9][8] If C. sativus is a mutant form of C. cartwrightianus, then it may have emerged via plant breeding, which would have selected for elongated stigmas, in late Bronze-Age Crete.[10]

Saffron's bitter taste and iodoform- or hay-like fragrance result from the chemicals picrocrocin and safranal.[11][12] It also contains a carotenoid dye, crocin, which imparts a rich golden-yellow hue to dishes and textiles. Its recorded history is attested in a 7th-century BC Assyrian botanical treatise compiled under Ashurbanipal,[13] and it has been traded and used for over four millennia. Iran now accounts for the lion's share, or around 90%, of world production.[14] Research into its many possible medicinal benefits, ranging from cancer suppression to mood improvement and appetite reduction, is ongoing.

Contents

Species

Description

The domesticated saffron crocus, Crocus sativus, is an autumn-flowering perennial plant unknown in the wild. It is often mistaken for the more plentiful common autumn crocus, Colchicum autumnale, which is also known as "meadow saffron" or "naked lady", causing deaths due to mistaken identity, though in high dosages saffron is also poisonous. It is a sterile triploid form, possibly of the eastern Mediterranean autumn-flowering Crocus cartwrightianus[15][8], which is also known as "wild saffron"[16] and originated in Central Asia.[12] "Triploid" means that three homologous sets of chromosomes compose each specimen's genetic complement; C. sativus bears eight chromosomal bodies per set, making for 24 in total.[1] The saffron crocus likely resulted when C. cartwrightianus was subjected to extensive artificial selection by growers seeking longer stigmas. C. thomasii and C. pallasii are other possible sources.[7][8] Being sterile, the purple flowers of Crocus sativus fail to produce viable seeds; reproduction hinges on human assistance: corms, underground bulb-like starch-storing organs, must be dug up, broken apart, and replanted. A corm survives for one season, producing via this vegetative division up to ten "cormlets" that can grow into new plants in the next season.[15] The compact corms are small brown globules that can measure as large as 5 centimetres (2.0 in) in diameter, have a flat base, and are shrouded in a dense mat of parallel fibers; this coat is referred to as the "corm tunic". Corms also bear vertical fibers, thin and net-like, that grow up to 5 cm above the plant's neck.[1]

The plant grows to a height of 20–30 cm (8–12 in), and sprouts 5–11 white and non-photosynthetic leafs known as cataphylls. They are membrane-like structures that cover and protect the crocus's 5–11 true leaves as they bud and develop. The latter are thin, straight, and blade-like green foliage leaves, which are 1–3 mm in diameter, either expand after the flowers have opened ("hysteranthous") or do so simultaneously with their blooming ("synanthous"). C. sativus cataphylls are suspected by some to manifest prior to blooming when the plant is irrigation relatively early in the growing season. Its floral axes, or flower-bearing structures, bear bracteoles, or specialised leaves that sprout from the flower stems; the latter are known as pedicels.[1] After aestivating in spring, the plant sends up its true leaves, each up to 40 cm (16 in) in length. In autumn, purple buds appear. Only in October, after most other flowering plants have released their seeds, do its brilliantly hued flowers develop; they range from a light pastel shade of lilac to a darker and more striated mauve.[17] Upon flowering, plants average less than 30 cm (12 in) in height.[18] A three-pronged style emerges from each flower. Each prong terminates with a vivid crimson stigma 25–30 mm (0.98–1.2 in) in length.[15]

Cultivation

Crocus sativus thrives in the Mediterranean maquis, an ecotype superficially resembling the North American chaparral, and similar climates where hot and dry summer breezes sweep semi-arid lands. It can nonetheless survive cold winters, tolerating frosts as low as −10 °C (14 °F) and short periods of snow cover.[15][19] Irrigation is required if grown outside of moist environments such as Kashmir, where annual rainfall averages1,000–1,500 mm (39–59 in); saffron-growing regions in Greece (500 mm or 20 in annually) and Spain (400 mm or 16 in) are far drier than the main cultivating Iranian regions. What makes this possible is the timing of the local wet seasons; generous spring rains and drier summers are optimal. Rain immediately preceding flowering boosts saffron yields; rainy or cold weather during flowering promotes disease and reduces yields. Persistently damp and hot conditions harm the crops,[20] and rabbits, rats, and birds cause damage by digging up corms. Nematodes, leaf rusts, and corm rot pose other threats. Yet Bacillus subtilis inoculation may provide some benefit to growers by speeding corm growth and increasing stigma biomass yield.[21]

Bihud, Iran.

The plants fare poorly in shady conditions; they grow best in full sunlight. Fields that slope towards the sunlight are optimal (i.e., south-sloping in the Northern Hemisphere). Planting is mostly done in June in the Northern Hemisphere, where corms are lodged 7–15 cm (2.8–5.9 in) deep; its roots, stems, and leaves can develop between October and February.[1] Planting depth and corm spacing, in concert with climate, are critical factors in determining yields. Mother corms planted deeper yield higher-quality saffron, though form fewer flower buds and daughter corms. Italian growers optimise thread yield by planting 15 cm (5.9 in) deep and in rows 2–3 cm (0.79–1.2 in) apart; depths of 8–10 cm (3.1–3.9 in) optimises flower and corm production. Greek, Moroccan, and Spanish growers employ distinct depths and spacings that suit their locales.

C. sativus prefers friable, loose, low-density, well-watered, and well-drained clay-calcareous soils with high organic content. Traditional raised beds promote good drainage. Soil organic content was historically boosted via application of some 20–30 tonnes of manure per hectare. Afterwards, and with no further manure application, corms were planted.[22] After a period of dormancy through the summer, the corms send up their narrow leaves and begin to bud in early autumn. Only in mid-autumn do they flower. Harvests are by necessity a speedy affair: after blossoming at dawn, flowers quickly wilt as the day passes.[23] All plants bloom within a window of one or two weeks.[24] Roughly 150 flowers together yield but 1 g (0.035 oz) of dry saffron threads; to produce 12 g (0.42 oz) of dried saffron (or 72 g (2.5 oz) moist and freshly harvested), 1 kg (2.2 lb) of flowers are needed; 1 lb (0.45 kg) yields 0.2 oz (5.7 g) of dried saffron. One freshly picked flower yields an average 30 mg (0.0011 oz) of fresh saffron or 7 mg (0.00025 oz) dried.[22]

Spice

Chemistry

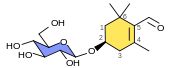

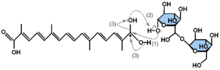

Saffron contains more than 150 volatile and aroma-yielding compounds. It also has many nonvolatile active components,[26] many of which are carotenoids, including zeaxanthin, lycopene, and various α- and β-carotenes. However, saffron's golden yellow-orange colour is primarily the result of α-crocin. This crocin is trans-crocetin di-(β-D-gentiobiosyl) ester; it bears the systematic (IUPAC) name 8,8-diapo-8,8-carotenoic acid. This means that the crocin underlying saffron's aroma is a digentiobiose ester of the carotenoid crocetin.[26] Crocins themselves are a series of hydrophilic carotenoids that are either monoglycosyl or diglycosyl polyene esters of crocetin.[26] Crocetin is a conjugated polyene dicarboxylic acid that is hydrophobic, and thus oil-soluble. When crocetin is esterified with two water-soluble gentiobioses, which are sugars, a product results that is itself water-soluble. The resultant α-crocin is a carotenoid pigment that may comprise more than 10% of dry saffron's mass. The two esterified gentiobioses make α-crocin ideal for colouring water-based and non-fatty foods such as rice dishes.[5]

The bitter glucoside picrocrocin is responsible for saffron's flavour. Picrocrocin (chemical formula: C16H26O7; systematic name: 4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-2,6,6- trimethylcyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxaldehyde) is a union of an aldehyde sub-element known as safranal (systematic name: 2,6,6-trimethylcyclohexa-1,3-diene-1-carboxaldehyde) and a carbohydrate. It has insecticidal and pesticidal properties, and may comprise up to 4% of dry saffron. Picrocrocin is a truncated version of the carotenoid zeaxanthin that is produced via oxidative cleavage, and is the glycoside of the terpene aldehyde safranal. The reddish-coloured zeaxanthin is, incidentally, one of the carotenoids naturally present within the retina of the human eye.[27]

When saffron is dried after its harvest, the heat, combined with enzymatic action, splits picrocrocin to yield D–glucose and a free safranal molecule.[25] Safranal, a volatile oil, gives saffron much of its distinctive aroma.[11][28] Safranal is less bitter than picrocrocin and may comprise up to 70% of dry saffron's volatile fraction in some samples.[27] A second element underlying saffron's aroma is 2-hydroxy-4,4,6-trimethyl-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one, the scent of which has been described as "saffron, dried hay like".[29] Chemists found this to be the most powerful contributor to saffron's fragrance despite its being present in a lesser quantity than safranal.[29] Dry saffron is highly sensitive to fluctuating pH levels, and rapidly breaks down chemically in the presence of light and oxidizing agents. It must therefore be stored away in air-tight containers in order to minimise contact with atmospheric oxygen. Saffron is somewhat more resistant to heat.

Grades

Saffron is graded via laboratory measurement of crocin (colour), picrocrocin (taste), and safranal (fragrance) content.[30] Determination of non-stigma content ("floral waste content") and other extraneous matter such as inorganic material ("ash") are also key. Grading standards are set by the International Organization for Standardization, a federation of national standards bodies. ISO 3632 deals exclusively with saffron and establishes four empirical colour intensity grades: IV (poorest), III, II, and I (finest quality). Samples are assigned grades by gauging the spice's crocin content, revealed by measurements of crocin-specific spectroscopic absorbance. Absorbance is defined as Aλ = − log(I / I0), with Aλ as absorbance (Beer-Lambert law) and indicates degree of transparency (I / I0, the ratio of light intensity exiting the sample to that of the incident light) to a given wavelength of light.

Graders measure absorbances of 440-nm light by dry saffron samples. Higher absorbances imply greater crocin concentration, and thus a greater colourative intensity. These data are measured through spectrophotometry reports at certified testing laboratories worldwide. These colour grades proceed from grades with absorbances lower than 80 (for all category IV saffron) up to 190 or greater (for category I). The world's finest samples (the selected most red-maroon tips of stigmas picked from the finest flowers) receive absorbance scores in excess of 250. Market prices for saffron types follow directly from these ISO scores. However, many growers, traders, and consumers reject such lab test numbers. They prefer a more holistic method of sampling batches of thread for taste, aroma, pliability, and other traits in a fashion similar to that practiced by practised wine tasters.[31]

Despite such attempts at quality control and standardisation, an extensive history of saffron adulteration—particularly among the cheapest grades—continues into modern times. Adulteration was first documented in Europe's Middle Ages, when those found selling adulterated saffron were executed under the Safranschou code.[32] Typical methods include mixing in extraneous substances like beets, pomegranate fibers, red-dyed silk fibers, or the saffron crocus's tasteless and odorless yellow stamens. Other methods included dousing saffron fibers with viscid substances like honey or vegetable oil. However, powdered saffron is more prone to adulteration, with turmeric, paprika, and other powders used as diluting fillers. Adulteration can also consist of selling mislabeled mixes of different saffron grades. Thus, in India, high-grade Kashmiri saffron is often sold and mixed with cheaper Iranian imports; these mixes are then marketed as pure Kashmiri saffron, a development that has cost Kashmiri growers much of their income.[33][34]

Varieties

The various saffron crocus cultivars give rise to thread types that are often regionally distributed and characteristically distinct. Varieties from Spain, including the tradenames "Spanish Superior" and "Creme", are generally mellower in colour, flavour, and aroma; they are graded by government-imposed standards. Italian varieties are slightly more potent than Spanish; the most intense varieties tend to be Iranian. Various "boutique" crops are available from New Zealand, France, Switzerland, England, the United States, and other countries, some of them organically grown. In the U.S., Pennsylvania Dutch saffron—known for its "earthy" notes—is marketed in small quantities.[35][36]

Consumers may regard certain cultivars as "premium" quality. The "Aquila" saffron, or zafferano dell'Aquila, is defined by high safranal and crocin content, distinctive thread shape, unusually pungent aroma, and intense colour; it is grown exclusively on eight hectares in the Navelli Valley of Italy's Abruzzo region, near L'Aquila. It was first introduced to Italy by a Dominican monk from Inquisition-era Spain. But the biggest saffron cultivation in Italy is in San Gavino Monreale, Sardinia, where it is grown on 40 hectares, representing 60% of Italian production; it too has unusully high crocin, picrocrocin, and safranal content. Another is the "Mongra" or "Lacha" saffron of Kashmir (Crocus sativus 'Cashmirianus'), which is among the most difficult for consumers to obtain. Repeated droughts, blights, and crop failures in the Indian-controlled areas of Kashmir combine with an Indian export ban to contribute to its prohibitive overseas prices. Kashmiri saffron is recognisable by its dark maroon-purple hue; it among the world's darkest, which hints at strong flavour, aroma, and colourative effect.

History

Main article: History of saffronThe documented history of saffron cultivation spans more than three millennia.[15] The wild precursor of domesticated saffron crocus was Crocus cartwrightianus. Human cultivators bred wild specimens by selecting for unusually long stigmas; thus, a sterile mutant form of C. cartwrightianus, C. sativus, likely emerged in late Bronze Age Crete.[10]

Eastern

Saffron was detailed in a 7th-century BC Assyrian botanical reference compiled under Ashurbanipal.[13] Documentation of saffron's use over the span of 4,000 years in the treatment of some 90 illnesses has been uncovered.[37] Saffron-based pigments have indeed been found in 50,000 year-old depictions of prehistoric places in northwest Iran.[38][39] The Sumerians later used wild-growing saffron in their remedies and magical potions.[40] Saffron was an article of long-distance trade before the Minoan palace culture's 2nd millennium BC peak. Ancient Persians cultivated Persian saffron (Crocus sativus 'Hausknechtii') in Derbena, Isfahan, and Khorasan by the 10th century BC. At such sites, saffron threads were woven into textiles,[38] ritually offered to divinities, and used in dyes, perfumes, medicines, and body washes.[41] Saffron threads would thus be scattered across beds and mixed into hot teas as a curative for bouts of melancholy. Non-Persians also feared the Persians' usage of saffron as a drugging agent and aphrodisiac.[42] During his Asian campaigns, Alexander the Great used Persian saffron in his infusions, rice, and baths as a curative for battle wounds. Alexander's troops imitated the practice from the Persians and brought saffron-bathing to Greece.[43]

Conflicting theories explain saffron's arrival in South Asia. Kashmiri and Chinese accounts date its arrival anywhere between 900–2500 years ago.[44][45][46] Historians studying ancient Persian records date the arrival to sometime prior to 500 BC,[5] attributing it to either Persian transplantation of saffron corms to stock new gardens and parks[47] or to a Persian invasion and colonization of Kashmir. Phoenicians then marketed Kashmiri saffron as a dye and a treatment for melancholy. Its use in foods and dyes subsequently spread throughout South Asia. Buddhist monks in India adopted saffron-coloured robes after the Gautama Buddha's death. This color is now used widely in all Buddhist countries. However, the robes were not dyed with costly saffron but turmeric, a less expensive dye, or jackfruit.[48] Gamboge is now used to dye the robes.[49]

Some historians believe that saffron came to China with Mongol invaders from Persia.[50] Yet saffron is mentioned in ancient Chinese medical texts, including the forty-volume pharmacopoeia titled Shennong Bencaojing (神農本草經: "Shennong's Great Herbal", also known as Pen Ts'ao or Pun Tsao), a tome dating from 200–300 BC. Traditionally credited to the fabled Yan ("Fire") Emperor (炎帝) Shennong, it discusses 252 phytochemical-based medical treatments for various disorders.[51] Nevertheless, around the 3rd century AD, the Chinese were referring to saffron as having a Kashmiri provenance. According to Chinese herbalist Wan Zhen, "[t]he habitat of saffron is in Kashmir, where people grow it principally to offer it to the Buddha." Wan also reflected on how it was used in his time: "The flower withers after a few days, and then the saffron is obtained. It is valued for its uniform yellow colour. It can be used to aromatise wine."[46]

Western

The Minoans portrayed saffron in their palace frescoes by 1500–1600 BC; they hint at its possible use as a therapeutic drug.[37][52] Ancient Greek legends told of sea voyages to Cilicia, where adventurers sought what they thought to be the world's most valued threads.[19] Another legend tells of Crocus and Smilax, whereby Crocus is bewitched and transformed into the first saffron crocus.[38] Ancient perfumers in Egypt, physicians in Gaza, townspeople in Rhodes,[53] and the Greek hetaerae courtesans used saffron in their scented waters, perfumes and potpourris, mascaras and ointments, divine offerings, and medical treatments.[42]

In late Hellenistic Egypt, Cleopatra used saffron in her baths so that lovemaking would be more pleasurable.[54] Egyptian healers used saffron as a treatment for all varieties of gastrointestinal ailments.[55] Saffron was also used as a fabric dye in such Levantine cities as Sidon and Tyre.[56] Aulus Cornelius Celsus prescribes saffron in medicines for wounds, cough, colic, and scabies, and in the mithridatium.[57] Such was the Romans' love of saffron that Roman colonists took it with them when they settled in southern Gaul, where it was extensively cultivated until Rome's fall. Competing theories state that saffron only returned to France with 8th-century AD Moors or with the Avignon papacy in the 14th century AD.[58]

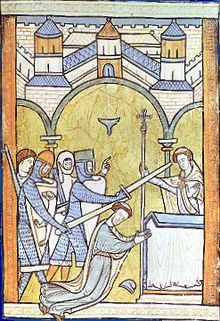

European saffron cultivation plummeted after the Roman Empire went into eclipse. As with France, the spread of Islamic civilization may have helped reintroduce the crop to Spain and Italy.[59] The 14th-century Black Death caused demand for saffron-based medicaments to peak, and large quantities of threads had to be imported via Venetian and Genoan ships from southern and Mediterranean lands such as Rhodes; the theft of one such shipment by noblemen sparked the fourteen-week long "Saffron War".[60] The conflict and resulting fear of rampant saffron piracy spurred corm cultivation in Basel; it thereby grew prosperous.[61] The crop then spread to Nuremberg, where endemic and insalubrious adulteration brought on the Safranschou code—whereby culprits were variously fined, imprisoned, and executed.[62] The corms soon spread throughout England, especially Norfolk and Suffolk. The Essex town of Saffron Walden, named for its new specialty crop, emerged as England's prime saffron growing and trading center. However, an influx of more exotic spices—chocolate, coffee, tea, and vanilla—from newly contacted Eastern and overseas countries caused European cultivation and usage of saffron to decline.[63][64] Only in southern France, Italy, and Spain did the clone significantly endure.[65]

Europeans introduced saffron to the Americas when immigrant members of the Schwenkfelder Church left Europe with a trunk containing its corms; church members had widely grown it in Europe.[35] By 1730, the Pennsylvania Dutch were cultivating saffron throughout eastern Pennsylvania. Spanish colonies in the Caribbean bought large amounts of this new American saffron, and high demand ensured that saffron's list price on the Philadelphia commodities exchange was set equal to that of gold.[66] The trade with the Caribbean later collapsed in the aftermath of the War of 1812, when many saffron-bearing merchant vessels were destroyed.[67] Yet the Pennsylvania Dutch continued to grow lesser amounts of saffron for local trade and use in their cakes, noodles, and chicken or trout dishes.[68] American saffron cultivation survived into modern times mainly in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[35]

Trade and use

Main article: Trade and use of saffronSaffron (Crocus sativus L.) Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) Energy 1,298 kJ (310 kcal) Carbohydrates 65.37 g - Dietary fiber 3.9 g Fat 5.85 g - saturated 1.586 g - monounsaturated 0.429 g - polyunsaturated 2.067 g Protein 11.43 g Water 11.90 g Vitamin A 530 IU Thiamine (vit. B1) 0.115 mg (10%) Riboflavin (vit. B2) 0.267 mg (22%) Niacin (vit. B3) 1.460 mg (10%) Vitamin C 80.8 mg (97%) Calcium 111 mg (11%) Iron 11.10 mg (85%) Magnesium 264 mg (74%) Phosphorus 252 mg (36%) Potassium 1724 mg (37%) Sodium 148 mg (10%) Zinc 1.09 mg (11%) Selenium 5.6 μg Folate[N 1] 93 μg Vitamin B6 1.010 mg Ash 5.45 g Edible thread portion only.[69]

Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults.

Source: USDA Nutrient DatabaseTrade

Almost all saffron grows in a belt bounded by the Mediterranean in the west and the rugged region encompassing Iran and disputed Kashmir in the east. The other continents, except Antarctica, produce smaller amounts. Some 300 t (300,000 kg) of dried whole threads and powder are gleaned yearly,[12] of which 50 t (50,000 kg) is top-grade "coupe" saffron.[70] Iran answers for around 90–93% of global production and exports much of it.[14] A few of Iran's drier eastern and southeastern provinces, including Fars, Kerman, and those in the Khorasan region, glean the bulk of modern global production. In 2005, the second-ranked Greece produced 5.7 t (5,700.0 kg), while Morocco and Kashmir, tied for third rank, each produced 2.3 t (2,300.0 kg).[14] Nevertheless, Iranian crop yields and profit margins on a per-acre basis are relatively low; margins in Spain, followed by Greece and Italy, are far higher.

In recent years, Afghan cultivation has risen; in restive Kashmir it has declined.[71] Azerbaijan, Morocco, and Italy are, in decreasing order, lesser producers. Prohibitively high labour costs and abundant Iranian imports mean that only select locales continue the tedious harvest in Austria, England, Germany, and Switzerland—among them the Swiss village of Mund, whose annual output is a few kilograms.[12]Tasmania,[72] China, Egypt, France, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Turkey (mainly around the town of Safranbolu), California, and Central Africa are microscale cultivators.[3][26]

To glean an amount of dry saffron weighing 1 lb (450 g) is to harvest 50,000–75,000 flowers, the equivalent of an association football field's area of cultivation; 110,000–170,000 flowers or two football fields are needed to gross one kilogram.[73][74] Forty hours of labour are needed to pick 150,000 flowers.[75] Stigmas are dried quickly upon extraction and (preferably) sealed in airtight containers.[76] Saffron prices at wholesale and retail rates range from US$500 to US$5,000 per pound, or US$1,100–11,000/kg, equivalent to £2,500/€3,500 per pound or £5,500/€7,500 per kilogram. The price in Canada recently rose to CAD 18,000 per kilogram. In Western countries, the average retail price is $1,000/£500/€700 per pound, or US$2,200/£1,100/€1,550 per kilogram.[3] A pound comprises between 70,000 and 200,000 threads. Vivid crimson colouring, slight moistness, elasticity, and lack of broken-off thread debris are all traits of fresh saffron.

Use

Saffron's aroma is often described by connoisseurs as reminiscent of metallic honey with grassy or hay-like notes, while its taste has also been noted as hay-like and sweet. Saffron also contributes a luminous yellow-orange colouring to foods. Saffron is widely used in European, Arab, South and Central Asian, Persian, and Turkish cuisines. Confectioneries and liquors also often include saffron. Common saffron substitutes include safflower (Carthamus tinctorius, which is often sold as "Portuguese saffron" or "açafrão"), annatto, and turmeric (Curcuma longa). Saffron has also been used as a fabric dye, particularly in China and India, and in perfumery.[77] It is used for religious purposes in India, and is widely used in cooking in many ethnic cuisines: these range, for example, from the Milanese risotto of Italy or the bouillabaise of France to biryani with various meat accompaniments in South Asia.

Saffron has a long medicinal history as part of traditional healing; modern medicine has also discovered saffron as having anticarcinogenic (cancer-suppressing), anti-mutagenic (mutation-preventing), immunomodulating, and antioxidant-like properties.[26][78][79] Saffron stigmas, and even petals, have been said to be helpful for depression.[80] Early studies show that saffron may protect the eyes from the direct effects of bright light and retinal stress apart from slowing down macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa.[81] (Most saffron-related research refers to the stigmas, but this is often not made explicit in research papers.)

Health benefits

Controlled research studies have indicated that saffron may have many potential medicinal uses:[82]

Conditions Suggested health benefits Referenced studies Premenstrual syndrome. Saffron was found to be effective in relieving symptoms of PMS or PMT.

Depression. Animal studies has shown that the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of saffron and its constituents, crocin and safranal, have antidepressant activities as revealed during forced swimming tests.

Obesity. "Satiereal", a novel extract of saffron stigma, may reduce snacking and enhance satiety through its suggested mood-enhancing effect. It may thereby help with weight loss.

Alzheimer's disease. A 2010 double-blind and placebo-controlled study found saffron helped mild to moderate the progression of symptoms in Alzheimer's patients.

Autoimmune diseasess and immune health. A 2011 double-blind human trial found use of 100 mg of saffron daily has temporary immunomodulatory activities.

Allergies. Crocus sativus inhibits histamine H1 receptors in animals, suggesting a potential use against allergic disorders. (Histamine is a biological amine that plays an important role in allergic responses.)

Heart disease. Saffron may have a protective effect on the heart.

Cancer (generalised). Crocetin, an important carotenoid constituent of saffron, has shown significant potential as an anti-tumor agent in animal models and cell culture systems.

Skin cancer Saffron inhibits DMBA-induced skin carcinoma in mice when the condition is treated early.

Breast cancer. Saffron, crocins, and crocetin inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation.

See also

Topics related to saffron: Saffron · History · Trade and use

Topics related to saffron: Saffron · History · Trade and useNotes

- ^ "Folate" refers only to the naturally occurring form of folic acid; the sample contains no folic acid per se.[69]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Kafi et al. 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Rau 1969, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Hill 2004, p. 272.

- ^ Grigg 1974, p. 287.

- ^ a b c McGee 2004, p. 422.

- ^ a b Rubio-Moraga et al. 2009.

- ^ a b Negbi 1999, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Caiola 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Negbi 1999, p. 30–31.

- ^ a b Negbi 1999, p. 1.

- ^ a b McGee 2004, p. 423.

- ^ a b c d Katzer 2001.

- ^ a b Russo, Dreher & Mathre 2003, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Ghorbani 2008, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Deo 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Kafi et al. 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Government of Tasmania 2005.

- ^ a b Willard 2002, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Deo 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Sharaf-Eldin et al. 2008.

- ^ a b Deo 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 4.

- ^ a b Deo 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Abdullaev 2002, p. 1.

- ^ a b Leffingwell 2002, p. 1.

- ^ Dharmananda 2005.

- ^ a b Leffingwell 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Verma & Middha 2010, p. 1–2.

- ^ Hill 2004, p. 274.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation 2003.

- ^ Hussain 2005.

- ^ a b c Willard 2002, p. 143.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 201.

- ^ a b Honan 2004.

- ^ a b c Willard 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Humphries 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Willard 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Lak 1998b.

- ^ Fotedar 1999, p. 128.

- ^ a b Dalby 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Dalby 2003, p. 256.

- ^ Finlay 2003, p. 224.

- ^ Hanelt 2001, p. 1352.

- ^ Fletcher 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Hayes 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Ferrence & Bendersky 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Marx 1989.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 70.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Willard 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Willard 2002, pp. 142–146.

- ^ a b United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Negbi 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Malik 2007.

- ^ Courtney 2002.

- ^ Hill 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Rau 1969, p. 35.

- ^ Lak 1998a.

- ^ Negbi 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Dalby 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Assimopoulou, Papageorgiou & Sinakos 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Chang et al. 1964, p. 1.

- ^ Bailes 1995.

- ^ Maccarone, Di Marco & Bisti 2008.

- ^ Moghaddasi 2010.

References

Books

- Bailes, M. (1995), The Healing Garden, Kangaroo Press (published February 1995), ISBN 978-0864176363

- Dalby, A. (2002), Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices (1st ed.), University of California Press (published 7 October 2002), ISBN 978-0520236745, http://books.google.com/?id=7IHcZ21dyjwC

- Dalby, A. (2003), Food in the Ancient World from A to Z, Routledge (published 18 June 2003), ISBN 978-0415232593

- Finlay, V. (2003), Colour: A Natural History of the Palette, Random House (published 30 December 2003), ISBN 978-0812971422

- Fletcher, N. (2005), Charlemagne's Tablecloth: A Piquant History of Feasting (1st ed.), Saint Martin's Press (published 28 July 2005), ISBN 978-0312340681

- Grigg, D. B. (1974), The Agricultural Systems of the World (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press (published 29 November 1974), ISBN 978-0521098434

- Hayes, A. W. (2001), Principles and Methods of Toxicology (4th ed.), Taylor and Francis (published 11 January 2001), ISBN 978-1560328148

- Hill, T. (2004), The Contemporary Encyclopedia of Herbs and Spices: Seasonings for the Global Kitchen (1st ed.), Wiley (published 10 September 2004), ISBN 978-0471214236

- Humphries, J. (1998), The Essential Saffron Companion, Ten Speed Press (published 1 August 1998), ISBN 978-1580080248

- Kafi, M. (editor); Koocheki, A. (editor); Rashed, M. H. (editor); Nassiri, M. (editor) (2006), Saffron (Crocus sativus) Production and Processing (1st ed.), Science Publishers (published 4 January 2006), ISBN 978-1578084272, http://books.google.com/books?id=kO8prjfiiCEC

- Kumar, V. (2006), The Secret Benefits of Spices and Condiments, Sterling Publishers (published 1 March 2006), ISBN 978-1845575854, http://books.google.com/books?id=AaTpWEIlgNwC

- Hanelt, P. (editor) (2001), Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricultural and Horticultural Crops (1st ed.), Springer (published 10 April 2001), ISBN 978-3540410171, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=10IMFSavIMsC

- Marx, F. (translator) (1989), Celsus: De Medicina, Loeb Classical Library, L292, Harvard University Press (published 1 July 1989), ISBN 978-0674993228, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Celsus/home.html, retrieved 15 September 2011

- McGee, H. (2004), On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, Scribner (published 16 November 2004), ISBN 978-0684800011, http://books.google.com/?id=iX05JaZXRz0C

- Negbi, M. (editor) (1999), Saffron: Crocus sativus L., CRC Press (published 23 June 1999), ISBN 978-9057023941, http://books.google.com/?id=l-QJaUp31T4C

- Rau, S. R. (1969), The Cooking of India, Foods of the World, Time-Life Books (published June 1969), ISBN 978-0809400690

- Russo, E.; Dreher, M. C.; Mathre, M. L. (2003), Women and Cannabis: Medicine, Science, and Sociology (1st ed.), Psychology Press (published March 2003), ISBN 978-0789021014

- Willard, P. (2002), Secrets of Saffron: The Vagabond Life of the World's Most Seductive Spice, Beacon Press (published 11 April 2002), ISBN 978-0807050095, http://books.google.com/?id=WsUaFT7l3QsC

Journal articles

- Abdullaev, F. I. (2002), "Cancer Chemopreventive and Tumoricidal Properties of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.)", Experimental Biology and Medicine 227 (1), PMID 11788779, http://www.ebmonline.org/cgi/content/full/227/1/20, retrieved 11 September 2011

- Agha-Hosseini, M.; Kashani, L.; Aleyaseen, A.; Ghoreishi, A.; Rahmanpour, H.; Zarrinara, A. R.; Akhondzadeh, S. (2008), "Crocus sativus L. (Saffron) in the Treatment of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Randomised, and Placebo-Controlled Trial", BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 115 (4): 515–519, March 2008, doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01652.x, PMID 18271889

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Sabet, M. S.; Harirchian, M. H.; Togha, M.; Cheraghmakani, H.; Razeghi, S.; Hejazi, S. S.; Yousefi, M.H. et al. (2010), "Saffron in the Treatment of Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease: A 16-week, Randomised, and Placebo-Controlled Trial", Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 35 (5): 581–588, October 2010, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01133.x, PMID 20831681

- Assimopoulou, A. N.; Papageorgiou, V. P.; Sinakos, Z. (2005), "Radical Scavenging Activity of Crocus sativus L. Extract and Its Bioactive Constituents", Phytotherapy Research 19 (11), PMID 16317646

- Boskabady, M. H.; Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Nemati, H.; Esmaeilzadeh, M. (2010), "Inhibitory Effect of Crocus sativus (Saffron) on Histamine (H1) Receptors of Guinea Pig Tracheal Chains", Die Pharmazie 65 (4): 300–305, April 2010, PMID 20432629

- Caiola, M. G. (2003), "Saffron Reproductive Biology", Acta Horticulturae (ISHS) 650: 25–37

- Chang, P. Y.; Kuo, W.; Liang, C. T.; Wang, C. K. (1964), "The Pharmacological Action of 藏红花 (Zà Hóng Huā—Crocus sativus L.): Effect on the Uterus and Estrous Cycle", Yao Hsueh Hsueh Pao 11

- Chryssanthi, D. G.; Dedes, P. G.; Karamanos, N. K.; Cordopatis, P.; Lamari, F. N. (2011), "Crocetin Inhibits Invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells via Downregulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases", Planta Medica 77 (2): 146–151, January 2011, doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250178, PMID 20803418

- Das, I.; Das, S.; Saha, T. (2010), "Saffron Suppresses Oxidative Stress in DMBA-Induced Skin Carcinoma: A Histopathological Study", Acta Histochemica 112 (4): 317–327, July 2010, doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2009.02.003, PMID 19328523

- Davies, N. W.; Gregory, M. J.; Menary, R. C. (2005), "Effect of Drying Temperature and Air Flow on the Production and Retention of Secondary Metabolites in Saffron", Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 53 (15): 5969–5975, doi:10.1021/jf047989j, PMID 16028982

- Deo, B. (2003), "Growing Saffron—The World's Most Expensive Spice", Crop and Food Research (New Zealand Institute for Crop and Food Research) (20), archived from the original on 27 December 2005, http://web.archive.org/web/20051227004245/http://www.crop.cri.nz/home/products-services/publications/broadsheets/020Saffron.pdf, retrieved 10 January 2006

- Dharmananda, S. (2005), "Saffron: An Anti-Depressant Herb", Institute for Traditional Medicine, archived from the original on 26 September 2006, http://web.archive.org/web/20060926130959/http://www.itmonline.org/arts/saffron.htm, retrieved 10 January 2006

- Ferrence, S. C.; Bendersky, G. (2004), "Therapy with Saffron and the Goddess at Thera", Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 47 (2): 199–226, doi:10.1353/pbm.2004.0026, PMID 15259204

- Ghorbani, M. (2008), "The Efficiency of Saffron's Marketing Channel in Iran", World Applied Sciences Journal 4 (4): 523–527, ISSN 1818-4952, http://www.idosi.org/wasj/wasj4%284%29/7.pdf, retrieved 3 October 2011

- Gout, B.; Bourges, C.; Paineau-Dubreuil, S. (2010), "Satiereal, a Crocus sativus L. Extract, Reduces Snacking and Increases Satiety in a Randomised Placebo-Controlled Study of Mildly Overweight, Healthy Women", Nutrition Research 30 (5): 305–313, May 2010, doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2010.04.008, PMID 20579522

- Gutheil, W. G.; Reed, G.; Ray, A.; Dhar, A. (2011), "Crocetin: An Agent Derived from Saffron for Prevention and Therapy for Cancer", Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 5 April 2011, PMID 21466430

- Hasegawa, J. H.; Kurumboor, S. K.; Nair, S. C. (1995), "Saffron Chemoprevention in Biology and Medicine: A Review", Cancer Biotherapy 10 (4), PMID 8590890

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Karimi, G.; Niapoor, M. (2004), "Antidepressant Effect of Crocus sativus L. Stigma Extracts and Their Constituents, Crocin and Safranal, In Mice", Acta Horticulturae (International Society for Horticultural Science) (650): 435–445, http://www.actahort.org/books/650/650_54.htm, retrieved 23 November 2009

- Jessie, S. W.; Krishnakantha, T. P. (2005), "Inhibition of Human Platelet Aggregation and Membrane Lipid Peroxidation by Saffron", Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 278 (1–2): 59–63, doi:10.1007/s11010-005-5155-9, PMID 16180089

- Joukar, S.; Najafipour, H.; Khaksari, M.; Sepehri, G.; Shahrokhi, N.; Dabiri, S.; Gholamhoseinian, A.; Hasanzadeh, S. (2010), "The Effect of Saffron Consumption on Biochemical and Histopathological Heart Indices of Rats with Myocardial Infarction", Cardiovascular Toxicology 10 (1): 66–71, March 2010, doi:10.1007/s12012-010-9063-1, PMID 20119744

- Kianbakht, S.; Ghazavi, A. (2011), "Immunomodulatory Effects of Saffron: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial", Phytotherapy Research, 8 April 2011, doi:10.1002/ptr.3484, PMID 21480412

- Moghaddasi, M. S. (2010), "Saffron Chemicals and Medicine Usage" (PDF), Journal of Medicinal Plant Research 4 (6): 427–430, 18 March 2010, http://www.academicjournals.org/jmpr/PDF/pdf2010/18Mar/Moghaddasi.pdf, retrieved 30 September 2011

- Maccarone, R.; Di Marco, S.; Bisti, S. (2008), "Saffron Supplement Maintains Morphology and Function after Exposure to Damaging Light in Mammalian Retina", Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 49 (3): 1254–1261, March 2008, doi:10.1167/iovs.07-0438, PMID 18326756, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/abstract/49/3/1254, retrieved 30 September 2011

- Nair, S. C.; Pannikar, B.; Panikkar, K. R. (1991), "Antitumour Activity of Saffron (Crocus sativus).", Cancer Letters 57 (2), PMID 2025883

- Rubio-Moraga, A.; Castillo-López, R.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Ahrazem, O. (2009), "Saffron is a Monomorphic Species as Revealed by RAPD, ISSR and Microsatellite Analyses", BMC Research Notes 2: 189, 23 September 2009, doi:10.1186/1756-0500-2-189, PMC 2758891, PMID 19772674, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2758891

- Sharaf-Eldin, M.; Elkholy, S.; Fernández, J. A.; Junge, H.; Cheetham, R.; Guardiola, J.; Weathers, P. (2008), "Bacillus subtilis FZB24 Affects Flower Quantity and Quality of Saffron (Crocus sativus)", Planta Med 74 (10): 1316–1320, August 2008, PMC 18622904, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=18622904

- Verma, R. S.; Middha, D. (2010), "Analysis of Saffron (Crocus sativus L. Stigma) Components by LC–MS–MS", Chromatographia 71 (1–2): 117–123, January 2010, doi:10.1365/s10337-009-1398-z, http://www.springerlink.com/content/505282x8x1766nk8/, retrieved 30 September 2011

Miscellaneous

- Courtney, P. (2002), "Tasmania's Saffron Gold", Landline (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 19 May 2002, http://www.abc.net.au/landline/stories/s556192.htm, retrieved 29 September 2011

- Fotedar, S. (1999), "Cultural Heritage of India: The Kashmiri Pandit Contribution", Vitasta (Kashmir Sabha of Kolkata) 32 (1), http://vitasta.org/1999/index.html, retrieved 15 September 2011

- Harper, D. (2001), Online Etymology Dictionary, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=saffron&searchmode=none, retrieved 12 September 2011

- Honan, W. H. (2004), "Researchers Rewrite First Chapter for the History of Medicine", The New York Times, 2 March 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/02/science/02MEDI.html?ex=1393563600, retrieved 13 September 2011

- Hussain, A. (2005), Saffron Industry in Deep Distress, London: BBC News (published 28 January 2005), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4216493.stm, retrieved 15 September 2011

- Katzer, G. (2001), "Saffron (Crocus sativus L.)", Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages, http://www.uni-graz.at/~katzer/engl/Croc_sat.html, retrieved 11 September 2011

- Lak, D. (1998), "Kashmiris Pin Hopes on Saffron", BBC News, 11 November 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/212491.stm, retrieved 11 September 2011

- Lak, D. (1998), "Gathering Kashmir's Saffron", BBC News, 23 November 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/213043.stm, retrieved 12 September 2011

- Leffingwell, J. C. (2002), "Saffron" (PDF), Leffingwell Reports 2 (5), October 2002, http://www.leffingwell.com/download/saffron.pdf, retrieved 15 September 2011

- Malik, N. (2007), Saffron Manual for Afghanistan, DACAAR Rural Development Program, http://www.icarda.org/Ralfweb/PDFs/SaffronManualForAfghanistan.pdf, retrieved 17 September 2011

- Park, J. B. (2005), "Saffron", USDA Phytochemical Database, archived from the original on 25 September 2006, http://web.archive.org/web/20060925041750/http://www.pl.barc.usda.gov/usda_supplement/supplement_detail_b.cfm?chemical_id=140, retrieved 10 January 2006

Other

- Kashmiri Saffron Producers See Red over Iranian Imports, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2003 (published 4 November 2003), http://www.abc.net.au/news/1504154, retrieved 29 September 2011

- "Emerging and Other Fruit and Floriculture: Saffron", Food and Agriculture (Department of Primary Industries, Water, and Environment (DPIWE), Government of Tasmania), 2005

- "Saffron", USDA National Nutrient Database (United States Department of Agriculture), http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search, retrieved 30 September 2011

External links

- "Saffron", Darling Biomedical Library (UCLA), http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=22

- "Crocus sativus", Germplasm Resources Information Network (USDA), http://sun.ars-grin.gov:8080/npgspub/xsql/duke/plantdisp.xsql?taxon=318

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.