- Tiger shark

-

Tiger shark

Temporal range: 50–0 Ma[1] Early Eocene to Present

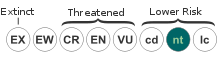

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Subclass: Elasmobranchii Order: Carcharhiniformes Family: Carcharhinidae Genus: Galeocerdo

J. P. Müller & Henle, 1837Species: G. cuvier Binomial name Galeocerdo cuvier

Péron & Lesueur, 1822

Tiger shark range Synonyms Squalus cuvier Peron and Lessueur, 1822

Galeocerdo tigrinus Müller and Henle, 1837The tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, is a species of requiem shark and the only member of the genus Galeocerdo. Commonly known as sea tigers, tiger sharks are relatively large macropredators, capable of attaining a length of over 5 m (16 ft).[3] It is found in many tropical and temperate waters, and is especially common around central Pacific islands. Its name derives from the dark stripes down its body which resemble a tiger's pattern and fade as the shark matures.[4]

The tiger shark is a solitary, mostly night-time hunter. Its diet involves a wide range of prey, including crustaceans, fish, seals, birds, smaller sharks, squid, turtles, sea snakes, and dolphins. The tiger shark is considered a near threatened species due to finning and fishing by humans.[2]

While the tiger shark is considered to be one of the sharks most dangerous to humans, the attack rate is surprisingly low according to researchers.[5] The tiger is second on the list of number of recorded attacks on humans, with the great white shark being first.[6][7] They often visit shallow reefs, harbors and canals, creating the potential for encounter with humans.[4]

Contents

Taxonomy

The shark was first described by Peron and Lessueur in 1822, and was given the name Squalus cuvier.[3] Müller and Henle in 1837 renamed it Galeocerdo tigrinus.[6] The genus, Galeocerdo, is derived from the Greek galeos which means shark and the Latin cerdus which means the hard hairs of pigs.[6] It is often colloquially called the man-eater shark.[6]

The tiger shark is a member of the order Carcharhiniformes.[3] Members of this order are characterized by the presence of a nictitating membrane over the eyes, two dorsal fins, an anal fin, and five gill slits. It is the largest member of the Carcharhinidae family, commonly referred to as requiem sharks. This family includes some other well-known sharks, such as the blue shark, lemon shark and bull shark.[4]

Range and habitat

The tiger shark is often found close to the coast, mainly in tropical and sub-tropical waters throughout the world.[6] Along with the great white shark, Pacific sleeper shark, Greenland shark and sixgill shark, tiger sharks are among the largest extant sharks.[6] Its behavior is primarily nomadic but is guided by warmer currents, and it stays closer to the equator throughout the colder months. It tends to stay in deep waters that line reefs, but it does move into channels to pursue prey in shallower waters. In the western Pacific Ocean, the shark has been found as far north as Japan and as far south as New Zealand.[3]

A number of tiger sharks can be seen at Gulf of Mexico, North American beaches and parts of South America. It is also commonly known in the Caribbean Sea. Other locations where tiger sharks are seen include Africa, People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, India, Australia, New Zealand and Eastern Europe.[4]

Certain tiger sharks have been recorded at depths just shy of 900 metres (3,000 ft)[6] but some sources claim they move into shallow water that is normally thought to be too shallow for a species of its size.[4] A recent study showed that the average tiger shark would be recorded at 350 metres (1,100 ft), making it uncommon to see tiger sharks in shallow water. However, tiger sharks in Hawaii have been observed in depths as shallow as 10ft and regularly observed in coastal waters at depths of 20 to 40 ft. They often visit shallow reefs, harbors and canals, creating the potential for encounters with humans.[8]

The tiger shark is known as tababa in Kiribati and Tuvaluan. Tiger sharks have been observed feeding in the tidal passages between the lagoon and ocean in Tarawa, Kiribati. Spring tides bring in plankton or animalcule, which attract small soft-shell crabs, which attract sardines, which attract the grey mullet, which attract the blue backed trevally (rereba), which then attract the tiger shark (tababa).[9]

Anatomy and appearance

Size

One of the largest sharks living today, the tiger shark commonly attains a length of 3 to 4.2 m (9.8 to 13.8 ft) and weighs around 385–635 kilograms (849–1,400 lb).[6] Sometimes a male tiger shark can grow up to 4.5 meters (14-15 feet long) and females to 5.5 meters (18 feet long). A tiger shark can sometimes rival a great white shark in size.[4] The tiger shark can grow up to 14-20 feet long.[3]

Biology

The skin of a tiger shark can typically range from blue to light green with a white or light yellow underbelly. Dark spots and stripes are most visible in young sharks and fade as the shark matures. Its head is somewhat wedge-shaped, which makes it easy to turn quickly to one side.[4][10] They have small pits on the side of their upper bodies which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini which enable them to detect electric fields, including the bio-electricity generated by prey.[11] Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line which extends on their flanks down most of the length of their sides. The primary role of this structure is to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations allow the tiger shark to hunt in darkness and detect hidden prey.[12]

A reflective layer behind the tiger shark's retina called the tapetum lucidum allows light-sensing cells a second chance to capture photons of visible light, enhancing vision in low light conditions. A tiger shark generally has long fins to provide lift as the shark maneuvers through water, while the long upper tail provides bursts of speed. Tiger sharks normally swim using small body movements.[13] Its high back and dorsal fin act as a pivot, allowing it to spin quickly on its axis, though the shark's dorsal fins are distinctively close to its tail.[11]

Its teeth are specialized to slice through flesh, bone, and other tough substances such as turtle shells. Like most sharks, however, its teeth are continually replaced by rows of new teeth.[11]

Diet

The tiger shark is an apex predator[14] and has a reputation for eating anything.[6] It also possesses the capability to take on large prey. It commonly preys upon fish (teleosts), crustaceans, mollusks, dugongs, seabirds, seasnakes,[15] marine mammals (e.g. bottlenose dolphins,[16] spotted dolphins[17]), and sea turtles (e.g. green and loggerhead turtles). The broad, heavily calcified jaws and nearly terminal mouth, combined with robust, serrated teeth, enable the tiger shark to take on these large prey.[18] In addition, excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell enable it to react to faint traces of blood and follow them to the source. Due to high risk of predatory attacks, dolphins often avoid regions inhabited by tiger sharks.[18] The tiger shark also eats other sharks (such as sandbar sharks) and will even eat conspecifics.[4]

Tiger sharks may also attack injured or ailing whales and prey upon them. A group was documented attacking and killing an ailing humpback whale in 2006 near Hawaii.[19] The tiger shark also scavenges on dead whales. In one such documented incident, they were observed scavenging on a whale carcass alongside great white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias.[20]

The ability to pick up low-frequency pressure waves enables the shark to advance towards an animal with confidence, even in murky water.[13] The shark circles its prey and studies it by prodding it with its snout.[13] When attacking, the shark often eats its prey whole.[13] Because of its aggressive feeding, it often mistakenly eats inedible objects, such as automobile license plates, oil cans, tires, and baseballs. For this reason, the tiger shark is often regarded as the ocean's garbage can.[4]

Swimming efficiency and stealth

All tiger sharks generally swim slowly, which, combined with cryptic coloration, may make them difficult for prey to detect them in some habitats. They are especially well camouflaged against dark backgrounds.[18] Despite their sluggish appearance, tiger sharks are one of the strongest swimmers of the carcharhinid sharks. Once the shark has come close, a speed burst allows it to reach the intended prey before it can escape.[18]

Reproduction

Males reach sexual maturity at 2.3 to 2.9 m (7.5 to 9.5 ft) and females at 2.5 to 3.5 m (8.2 to 11 ft).[11] Females mate once every 3 years.[4] They breed by internal fertilization. The male inserts one of his claspers into the female's genital opening (cloaca), acting as a guide for the sperm. The male uses its teeth to hold the female still during the procedure, often causing the female considerable discomfort. Mating in the northern hemisphere generally takes place between March and May, with birth between April and June the following year. In the southern hemisphere, mating takes place in November, December, or early January. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed.[6]

The young develop inside the mother's body for up to 16 months. Litters range from 10 to 80 pups.[6] A newborn is generally 51 centimetres (20 in) to 76 centimetres (30 in) long.[6] This shark typically reaches maturity at lengths of 2 to 3 m (6.6 to 9.8 ft).[6][11] It is unknown how long tiger sharks live, but they can live longer than 12 years.[4]

Dangers and conservation

Although shark attacks are a relatively rare phenomenon, the tiger shark is responsible for a large percentage of fatal attacks and is regarded as one of the most dangerous shark species.[7][21] Tiger sharks are often found in river estuaries and harbors as well as shallow water close to shore where they are bound to encounter humans. The tiger shark also dwells in river mouths and other runoff-rich water.[6][11] On average, 3 to 4 shark attacks occur per year in Hawaii and most attacks are non-fatal. This attack rate is surprisingly low considering that thousands of people swim, surf and dive in Hawaiian waters every day.[5] A notable tiger shark attack made headlines in October of 2003 when (then 13-year-old) American surfer Bethany Hamilton lost her arm near her shoulder. Despite the attack, she returned to surfing a short time later.[22] Hamilton is now a professional surfer and inspirational speaker. A large tiger shark was killed and hung, and later measured to be presumably matching the size and bite pattern of the shark which attacked Hamilton. As of 2009 there have been 119 attacks, 29 fatal.

Between 1959 and 1976, 4,668 tiger sharks were culled in an effort to protect the tourism industry. Despite these efforts attacks did not decrease. It is illegal to feed sharks in Hawaii, and interaction with them, such as cage diving, is discouraged.[23] South African shark scientist Mark Addison demonstrated that they could be tamed somewhat in a 2007 Discovery Channel special.[24]

The tiger shark is captured and killed for its fins, flesh, and liver. It is caught regularly in target and non-target fisheries. There is evidence of declines for several populations where they have been heavily fished, but in general they do not face a high risk of extinction. However, continued demand, especially for fins, may result in further declines in the future. Tiger sharks are considered a near threatened species due to excessive finning and fishing by humans according to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[2]

While shark fin has very few nutrients, shark liver has a high concentration of vitamin A which is used in the production of vitamin oils. In addition, the tiger shark is captured and killed for its distinct skin as well as by big game fishers.[6]

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the tiger shark to its seafood red list. The Greenpeace International seafood red list is a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets around the world, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries.[25]

Mythology

The tiger shark is considered to be sacred na ʻaumakua (ancestor spirits) by some native Hawaiians who think their eyeballs have special seeing powers. This aligns with the general known facts about sharks and their highly developed senses.[5]

See also

- For a topical guide to this subject, see Outline of sharks.

- List of sharks

- List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish

- List of fatal, unprovoked shark attacks in the United States by decade

Notes

- ^ Sepkoski

- ^ a b c Simpfendorfer

- ^ a b c d e Froese & Pauly

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ritter (1999b)

- ^ a b c Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Knickle

- ^ a b International Shark Attack File

- ^ Lad

- ^ Grimble, Sir Arthur (1952). "A Pattern of Islands; Ch. 5 Lagoon Days". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC). http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-GriPatt.html. Retrieved 16 Oct. 2011.

- ^ Canadian Shark Research Laboratory

- ^ a b c d e f MarineBio

- ^ New Brunswick

- ^ a b c d Lady Wildlife

- ^ Heithaus (2001a)

- ^ Heithaus (2004)

- ^ Heithaus (2002)

- ^ Maldini

- ^ a b c d Heithaus (2001b)

- ^ Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

- ^ Dudley

- ^ Ritter (1999a)

- ^ Hamilton

- ^ Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council

- ^ Donahue

- ^ Greenpeace

Sources

- Canadian Shark Research Laboratory, Tiger Shark - Centre for Marine Biodiversity. Marine Biodiversity. Retrieved July 2011.

- Donahue, Ann (30 July 2007). "Shark Week: 'Deadly Stripes: Tiger Sharks'". LA Times. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/showtracker/2007/07/shark-week-dead.html. Retrieved July 2011.

- Dudley, Sheldon F. J.; Michael D. Anderson-Reade, Greg S. Thompson, and Paul B. McMullen (2000). "Concurrent scavenging off a whale carcass by great white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, and tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier" (PDF). Marine Biology. Fishery Bulletin. http://fishbull.noaa.gov/983/13.pdf. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2011). "Galeocerdo cuvier" in FishBase. July 2011 version.

- Greenpeace International Seafood Red list

- Hamilton, Bethany (2003). "About Me". Bethany's General Biography. BethanyHamilton.com. http://bethanyhamilton.com/about/. Retrieved July 2011.

- "Tiger Shark Research Program". Shark & Reef Fish Research. Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. http://www2.hawaii.edu/~carlm/tigershark.html. Retrieved July 2011.

- Heithaus, Michael R. (2001). "The biology of tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, in Shark Bay, Western Australia: sex ratio, size distribution, diet, and seasonal changes in catch rates". Environmental Biology of Fishes 61: 25–36. doi:10.1023/A:1011021210685.

- Heithaus, Michael R. (2001). "Copyright: Predator–prey and competitive interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (suborder Odontoceti): a review". Journal of Zoology 253: 53–68. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000061.

- HEITHAUS, MICHAEL; DILL, LAWRENCE (2002). "FOOD AVAILABILITY AND TIGER SHARK PREDATION RISK INFLUENCE BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN HABITAT USE". Ecological Society of America 83 (2): 480–491. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0480:FAATSP]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0012-9658. http://www.monkeymiadolphins.org/Pdf/Heithaus%20and%20Dill%202002.pdf.

- HEITHAUS, M. R.; L. M. DILL, G. J. MARSHALL, and B. BUHLEIER (2004). "Habitat use and foraging behavior of tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) in a seagrass ecosystem". Marine Biology (Australia: Springer) 140 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1007/s00227-001-0711-7. http://www.bio.miami.edu/prince/Sharks.pdf.

- "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". International Shark Attack File. Florida Museum of Natural History University of Florida. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/Statistics/species2.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- Knickle, Craig. "Tiger Shark Biological Profile". Florida Museum of Natural History Icthyology Department. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Gallery/Descript/Tigershark/tigershark.htm. Retrieved July 2011.

- Lad, Kashmira. Habitat of a Tiger Shark. Buzzle. Retrieved July 2011.

- "Tiger Shark". ladywildlife.com. http://ladywildlife.com/animals/tigershark.html. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- Maldini, Daniela (2003). "Evidence of predation by a tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) on a spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuata) off Oahu, Hawaii". Aquatic Mammals (Hawaii: European Association for Aquatic Mammals) 29 (1): 84–87. doi:10.1578/016754203101023915. http://www.alaskasealife.org/New/Contribute/pdf/Maldini_2003.pdf.

- Tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier MarineBio" Accessed July, 2011.

- Tiger Shark - The Province of New Brunswick Canada. New Brunswick. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. "Humpback Whale Shark Attack: A Natural Phenomenon Caught on Camera". http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/features/1106_sharkattack.html. Retrieved July, 2011.

- Ritter, Erich K. (15 February 1999). "Which shark species are really dangerous?". Shark Info. http://www.sharkinfo.ch/SI1_99e/attacks2.html. Retrieved July 2011.

- Ritter, Erich K. (15 December 1999). "Fact Sheet: Tiger Sharks". Shark Info. http://www.sharkinfo.ch/SI4_99e/gcuvier.html. Retrieved July 2011.

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera (Chondrichthyes entry)". Bulletins of American Paleontology 450: 560. http://strata.ummp.lsa.umich.edu/jack/showgenera.php?taxon=575&rank=class. Retrieved July 2011.

- Simpfendorfer (2005). "Galeocerdo cuvier". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/39378. Retrieved July 2011.

- "Federal Fishery Managers Vote To Prohibit Shark Feeding". Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. http://www.wpcouncil.org/press/2006Oct23_PRESSRELEASE_135CM.pdf. Retrieved July 2011.

External links

- "Galeocerdo cuvier". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=160189. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- Tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier at the Encyclopedia of Life

- General information Enchanted Learning. Retrieved January 22, 2005.

- Different diet information Shark Info. Retrieved January 22, 2005.

- Tiger sharks in Hawaii Research program. Retrieved January 22, 2005.

- Tiger shark: Fact File from National Geographic

- Tracking research on tiger sharks

- Pictures of tiger sharks

- Tiger shark documented killing a Sea Turtle (Adobe flashplayer warning)

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Carcharhinidae

- Ovoviviparous fish

- Fish of Hawaii

- Animals described in 1822

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.