- Culling

-

"Cull" redirects here. For people with the surname "Cull", see Cull (surname).

Culling is the process of removing animals from a group based on specific criteria. This is done either to reinforce certain desirable characteristics or to remove certain undesirable characteristics from the group. For livestock and wildlife, the process of culling usually implies the killing of animals with undesirable characteristics.

Contents

Origin of the term

The word comes from the Latin colligere, which means collect. The term can be applied broadly to mean sorting a collection into two groups: one that will be kept and one that will be rejected. The cull is the set of items rejected during the selection process. For example, if you were to cull a collection of marbles such that only red marbles are chosen, the cull would be the set of marbles that are not red. In this example, the selection process would be culling on red marbles. The implicit meaning is that the cull (the non-red marbles) are going to be the group rejected.

The culling process is repeated until the selected group is of proper size and consistency desired. Take for example a talent contest. During the first round all the contestants compete and are evaluated. Since only a limited number of the contestants can continue to the next round of the competition, the group is culled based on the judge's opinions. Those contestants that are not selected to continue are culled from the group. During the second round, the contestants perform again, have their performances judged, and are culled again based on the judges scoring. This process continues until the finalists and eventually the winner of the contest is chosen. By more stringently applying the selection criteria on each round of the competition, the judges are able to cull the group to the single individual that they felt performed the best during the competition.

Pedigreed animals

Culling The rejection or removal of inferior individuals from breeding. The act of selective breeding. As used in the practice of breeding pedigree cats, this refers to the practice of spaying or neutering a kitten or cat that does not measure up to the show standard (or other standard being applied) for that breed. In no way does culling, as used by responsible breeders, signify the killing of healthy kittens or cats if they fail to meet the applicable standard."

Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians, Fourth Edition[1]In the breeding of pedigreed animals, both desirable and undesirable traits are considered when choosing which animals to retain for breeding and which to place as pets. The process of culling starts with examination of the conformation standard of the animal and will often include additional qualities such as health, robustness, temperament, color preference, etc. The breeder takes all things into consideration when envisioning his/her ideal for the breed or goal of their breeding program. From that vision, selections are made as to which animals, when bred, have the best chance of producing the ideal for the breed.[2]

Breeders of pedigreed animals cull based on many criteria. The first culling criterion should always be health and robustness. Secondary to health, temperament and conformation of the animal should be considered. The filtering process ending with the breeders personal preferences on pattern, color, etc.

The Tandem Method

The Tandem Method is a form of selective breeding where a breeder addresses one characteristic of the animal at a time. Thus selecting only animals that measure above a certain threshold for that particular trait while keeping other traits constant. Once that level of quality in the single trait is achieved, the breeder will focus on a second trait and cull based on that quality.[2] With the tandem method, a minimum level of quality is set for important characteristics that the breeder wishes to remain constant. The breeder is focussing improvement in one particular trait without losing quality of the others. The breeder will raise the threshold for selection on this trait with each successive generation of progeny. Thus insuring improvement in this single characteristic of his breeding program.

For example, lets say that a breeder is pleased with the muzzle length, muzzle shape, and eye placement in her breeding stock, but wishes to improve the eye shape of progeny produced. The breeder then determines a minimum level of improvement in eye shape required for her to fold progeny back into her breeding program. Progeny is first evaluated on the existing quality thresholds in place for muzzle length, muzzle shape, and eye placement with the additional criteria being improvement in eye shape. Any animal that does not meet this level of improvement in the eye shape while maintaining the other qualities is culled from the breeding program; i.e., that animal is not used for breeding, but is instead spayed/neutered and placed in a pet home.

Independent levels

Independent levels is a method where any animal who falls below a given standard in any single characteristic is not used in a breeding program. With each successive mating, the threshold culling criteria is raised thus improving the breed with each successive generation.[2]

This method measures several characteristics at once. Should progeny fall below the desired quality in any one characteristic being measured, it will be not be used in the breeding program regardless of the level of excellence of other traits. With each successive generation of progeny, the minimum quality of each characteristic is raised thus insuring improvement of these traits.

For example, a breeder has a view of what the minimum requirements for muzzle length, muzzle shape, eye placement, and eye shape she is breeding toward. The breeder will determine what the minimum acceptable quality for each of these traits will be for progeny to be folded back into her breeding program. Any animal that fails to meet the quality threshold for any one of these criteria is culled from the breeding program.

Total Score Method

The Total Score Method is a method where the breeder evaluates and selects breeding stock based on a weighted table of characteristics. The breeder selects qualities that are most important to them and assigns them a weight. The weights of all the traits should add up to 100. When evaluating an individual for selection, the breeder measures the traits on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most desirable expression and 1 being the lowest. The scores are then multiplied by their weights and then added together to give a total score. Individuals that fail to meet a threshold are culled (or removed) from the breeding program. The total score gives a breeder a way to evaluate multiple traits on an animal at the same time.[2]

The total score method is the most flexible of the three. it allows for weighted improvement of multiple characteristics. It allows the breeder to make major gains in one aspect while moderate or lesser gains in others.

For example, a breeder is willing to make a smaller improvement in muzzle length and muzzle shape in order to have a moderate gain in improvement of eye placement and a more dramatic improvement in eye shape. Suppose the breeder determines that she would like to see 40% improvement in eye shape, 30% improvement in eye placement, and 15% improvement in both muzzle length and shape. The breeder would evaluate these characteristics on a scale of 1 to 10 and multiply by the weights. The formula would look something like: 15 (muzzle length) + 15(muzzle shape) + 30(eye placement) + 40(eye shape) = total score for that animal. The breeder determines the lowest acceptable total score for an animal to be folded back into their breeding program. Animals that do not meet this minimum total score are culled from the breeding program.

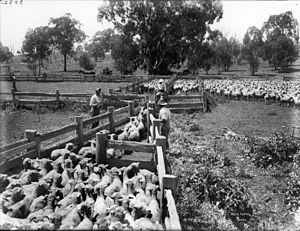

Livestock and production animals

See also: Chick cullingSince livestock is bred for the production of meat or milk, the herd must be culled to a certain number of production or meat animals a farmer wishes to maintain. Animals not selected to remain for breeding are sent to the slaughter house, sold, or killed.

Criteria for culling livestock and production animals can be based on population or production (milk or egg). In a domestic or farming situation the culling process involves selection and the selling of surplus stock. The selection may be done to improve breeding stock, for example for improved production of eggs or milk, or simply to control the group's population for the benefit of the environment and other species.

With dairy cattle, culling may be practised by inseminating inferior cows with beef breed semen and by selling the produced offspring for meat production.

With poultry, males which would grow up to be roosters have little use in an industrial egg-producing facility. Approximately half of the newly hatched chicks will be male and would grow up to be roosters, which do not lay eggs. For this reason, the hatchlings are culled based on gender. Most of the male chicks are usually killed shortly after hatching.

Wildlife

In the United States, hunting licenses and hunting seasons are a means by which the population of game animals is maintained. Each season, a hunter is allowed to kill a certain amount of wild game. The amount is determined both by species and gender. If the population seems to have surplus females, hunters are allowed to take more females during that hunting season. If the population is below what is desired, hunters may not be permitted to hunt that particular game animal or only hunt a restricted number of males.

Populations of game animals such as elk may be informally culled if they begin to excessively eat winter food set out for domestic cattle herds. In such instances the rancher will inform hunters that they may "hunt the haystack" on his property in order to thin the wild herd to controllable levels. These efforts are aimed to counter excessive depletion of the intended "domestic" winter feed supplies. Other managed culling instances involve extended issuance of extra hunting licenses, or the inclusion of additional "special hunting seasons" during harsh winters or overpopulation periods, governed by state fish and game Agencies.

Culling for population control is common in wildlife management, particularly on African game farms and in Australia in national parks. In the case of very large animals such as elephants, adults are often targeted. Their orphaned young, easily captured and transported, are then relocated. Without proper elephant socialization, young male elephants are believed to become unruly and extremely dangerous to other elephants, wildlife and humans.[3] Culling is controversial in many African countries, but reintroduction of the practice has been recommended in recent years for use at the Kruger National Park in South Africa, which has experienced a swell in its elephant population since culling was banned in 1995.[4]

In fishing tournaments, culling refers to releasing smaller fish that will not be used to count towards an angler's total weight. For instance, if an angler is allowed to weigh in only 4 fish, he might keep his first four 2 pound fish in the livewell until he starts to catch bigger fish. As he catches bigger fish, he can release (or cull) the smaller fish.

In certain cases culling may also be undertaken to check outbreak of certain viral or other infections and diseases among animals or birds. This has become widespread in India and some other East Asian countries where there are outbreaks of the deadly Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 among poultry. Huge numbers of chickens and some other fowls are being culled (as of December 2008) in order to contain spread of the avian flu.

Culling would require a lot of safety steps to be maintained in such cases of culling animals/birds since even a minor fault can cause the infections to spread out from the affected animals/birds to the population at large. Safety measures may include wearing special protective clothing and breathing apparatus to keep the workers culling the affected animals/birds from getting infected.

See also

- Animal population control

- Artificial selection

- Experimental evolution

- Nuisance wildlife management

- Selective breeding

References

- ^ Carolyn M. Vella, Lorraine M. Shelton, John J. McGonagle, Terry W. Stanglein, Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians, Fourth Edition, page 212

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Roy; Carolyn M. Vella, Lorraine M. Shelton, John J. McGonagle, Terry W. Stanglein (1999). Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians (Fourth ed.). Great Britain: Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 0750640693.

- ^ Siebert, Charles (2006-10-08). An Elephant Crackup?. The New York Times Magazine. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/08/magazine/08elephant.html?_r=1&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2008-02-10

- ^ Nduru, Moyiga (2005-12-05). "Is 'Cull' a Four-Letter Word?". Inter Press Service. http://www.ipsnews.net/interna.asp?idnews=31297. Retrieved 2006-05-12.

External links

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.