- Bath, Somerset

-

Coordinates: 51°23′N 2°22′W / 51.38°N 2.36°W

City of Bath

The Royal Crescent in Bath

City of Bath shown within Somerset

City of Bath shown within SomersetPopulation 83,992 [1] OS grid reference ST745645 - London 99 miles (159 km) E Unitary authority Bath and North East Somerset Ceremonial county Somerset Region South West Country England Sovereign state United Kingdom Post town BATH Postcode district BA1, BA2 Dialling code 01225 Police Avon and Somerset Fire Avon Ambulance Great Western EU Parliament South West England UK Parliament Bath List of places: UK • England • Somerset Bath (

/ˈbɑːθ/ or /ˈbæθ/) is a city in the ceremonial county of Somerset in the south west of England. It is situated 97 miles (156 km) west of London and 13 miles (21 km) south-east of Bristol. The population of the city is 83,992.[1] It was granted city status by Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth I in 1590,[2] and was made a county borough in 1889 which gave it administrative independence from its county, Somerset. The city became part of Avon when that county was created in 1974. Since 1996, when Avon was abolished, Bath has been the principal centre of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset (B&NES).

/ˈbɑːθ/ or /ˈbæθ/) is a city in the ceremonial county of Somerset in the south west of England. It is situated 97 miles (156 km) west of London and 13 miles (21 km) south-east of Bristol. The population of the city is 83,992.[1] It was granted city status by Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth I in 1590,[2] and was made a county borough in 1889 which gave it administrative independence from its county, Somerset. The city became part of Avon when that county was created in 1974. Since 1996, when Avon was abolished, Bath has been the principal centre of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset (B&NES).The city was first established as a spa with the Latin name, Aquae Sulis ("the waters of Sulis") by the Romans in AD 43, although verbal tradition suggests that Bath was known before then.[3] They built baths and a temple on the surrounding hills of Bath in the valley of the River Avon around hot springs.[4] Edgar was crowned king of England at Bath Abbey in 973.[5] Much later, it became popular as a spa town during the Georgian era, which led to a major expansion that left a heritage of exemplary Georgian architecture crafted from Bath Stone.

The City of Bath was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1987. The city has a variety of theatres, museums, and other cultural and sporting venues, which have helped to make it a major centre for tourism, with over one million staying visitors and 3.8 million day visitors to the city each year.[6] The city has two universities and several schools and colleges. There is a large service sector, and growing information and communication technologies and creative industries, providing employment for the population of Bath and the surrounding area.

Contents

History

Iron Age and Roman

The Great Bath at the Roman Baths. The entire structure above the level of the pillar bases is a later reconstruction.

The Great Bath at the Roman Baths. The entire structure above the level of the pillar bases is a later reconstruction.

The hills around Bath such as Bathampton Down saw human activity from the Mesolithic period.[7][8] Several Bronze Age round barrows were opened by John Skinner in the 18th century.[9] Bathampton Camp may have been an Iron Age hill fort or stock enclosure.[10][11] A Long barrow site believed to be from the Beaker people was flattened to make way for RAF Charmy Down.[12]

Archaeological evidence shows that the site of the Roman Baths' main spring was treated as a shrine by the Iron Age Britons,[13] and was dedicated to the goddess Sulis, whom the Romans identified with Minerva; however, the name Sulis continued to be used after the Roman invasion, leading to the town's Roman name of Aquae Sulis (literally, "the waters of Sulis").[14] Messages to her scratched onto metal, known as curse tablets, have been recovered from the Sacred Spring by archaeologists.[15] These curse tablets were written in Latin, and usually laid curses on people by whom the writer felt they had been wronged. For example, if a citizen had his clothes stolen at the baths, he would write a curse, naming the suspects, on a tablet to be read by the Goddess Sulis Minerva.

The temple was constructed in 60–70 AD and the bathing complex was gradually built up over the next 300 years.[4] During the Roman occupation of Britain, and possibly on the instructions of Emperor Claudius,[16] engineers drove oak piles into the mud to provide a stable foundation and surrounded the spring with an irregular stone chamber lined with lead. In the 2nd century, the spring was enclosed within a wooden barrel-vaulted building,[13] which housed the calidarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath), and frigidarium (cold bath).[17] The city was given defensive walls, probably in the 3rd century.[18] After the failure of Roman authority in the first decade of the 5th century, the baths fell into disrepair and were eventually lost due to silting up.[19]

Post-Roman and Mediaeval

Bath may have been the site of the Battle of Mons Badonicus (c. 500 AD), where King Arthur is said to have defeated the Anglo-Saxons, although this is disputed.[20] The city fell to the West Saxons in 577 after the Battle of Deorham;[21][21] the Anglo-Saxon poem known as The Ruin may describe the appearance of the Roman site about this time.[22] A monastery was set up in Bath at an early date – reputedly by Saint David, though more probably in 675 by Osric, King of the Hwicce,[23] perhaps using the walled area as its precinct.[24][25] Nennius, a ninth-century historian, mentions a "Hot Lake" in the land of the Hwicce, which was along the Severn, and adds "It is surrounded by a wall, made of brick and stone, and men may go there to bathe at any time, and every man can have the kind of bath he likes. If he wants, it will be a cold bath; and if he wants a hot bath, it will be hot". Bede also describes hot baths in the geographical introduction to the Ecclesiastical History in terms very similar to those of Nennius.[26] King Offa of Mercia gained control of this monastery in 781 and rebuilt the church, which was dedicated to St. Peter.[27]

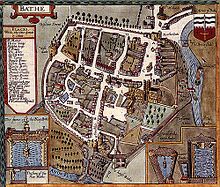

By the 9th century the old Roman street pattern had been lost and Bath had become a royal possession, with King Alfred laying out the town afresh, leaving its south-eastern quadrant as the abbey precinct.[28] In the Burghal Hidage Bath is described as having walls of 1,375 yards (1,257 m) and was allocated 1000 men for defence.[29] During the reign of Edward the Elder coins were minted in the town, based on a design from the Winchester mint but with 'BAD' on the obverse relating to the Anglo-Saxons name for the town Baðum, Baðan or Baðon, meaning "at the baths,"[30] and this was the source of the present name. Edgar of England was crowned king of England in Bath Abbey in 973.[5]

King William Rufus granted the city to a royal physician, John of Tours, who became Bishop of Wells and Abbot of Bath,[31][32] following the sacking of the town during the Rebellion of 1088.[33] It was papal policy for bishops to move to more urban seats, and he translated his own from Wells to Bath.[34] He planned and began a much larger church as his cathedral, to which was attached a priory, with the bishop's palace beside it.[31] New baths were built around the three springs. However, later bishops returned the episcopal seat to Wells, while retaining the name of Bath in their title as the Bishop of Bath and Wells. St John's Hospital was founded around 1180, by Bishop Reginald Fitz Jocelin and is among the oldest almshouses in England.[35] The 'hospital of the baths' was built beside the hot springs of the Cross Bath, for their health giving properties and to provide shelter for the poor infirm.[36]

Administrative systems fell within the Hundreds. The Bath Hundred had various names over the centuries including The Hundred of Le Buri. The Bath Foreign Hundred or Forinsecum covered the area outside the city itself. They were later combined into the Bath Forum Hundred. The wealthy merchants had no status within the Hundred Courts and formed guilds to gain influence, they also built the first guildhall probably in the 13th century. Around 1200 the first mayor was also appointed.[37]

Early Modern

By the 15th century, Bath's abbey church was badly dilapidated and in need of repairs.[38] Oliver King, Bishop of Bath and Wells, decided in 1500 to rebuild it on a smaller scale. The new church was completed just a few years before Bath Priory was dissolved in 1539 by Henry VIII.[39] The abbey church was allowed to become derelict before being restored as the city's parish church in the Elizabethan era, when the city experienced a revival as a spa. The baths were improved and the city began to attract the aristocracy. Bath was granted city status by Royal charter by Queen Elizabeth I in 1590.[2]

During the English Civil War, the city was garrisoned for King Charles the 1st and seven thousand pounds spent on fortifications. However upon the appearance of parliamantary forces the gates were thrown open and the city surrendered, and it then become a significant post in Somerset for the New Model Army under William Waller.[40] It was retaken by royalists following the Battle of Lansdowne which was fought on 5 July 1643 on the northern outskirts of the city.[41] Thomas Guidott, who had been a student of chemistry and medicine at Wadham College, Oxford, moved to Bath and set up practice in 1668. He became interested in the curative properties of the waters and he wrote A discourse of Bathe, and the hot waters there. Also, Some Enquiries into the Nature of the water in 1676. This brought the health-giving properties of the hot mineral waters to the attention of the country and soon the aristocracy started to arrive to partake in them.[42]

The Royal Crescent from the air: Georgian taste favoured the regularity of Bath's streets and squares and the contrast with adjacent rural nature.

The Royal Crescent from the air: Georgian taste favoured the regularity of Bath's streets and squares and the contrast with adjacent rural nature.

Several areas of the city underwent development during the Stuart period, and this increased during Georgian times in response to the increasing number of visitors to the spa and resort town who required accommodation.[43] The architects John Wood the elder and his son John Wood the younger laid out the new quarters in streets and squares, the identical façades of which gave an impression of palatial scale and classical decorum.[44] Much of the creamy gold Bath Stone used for construction throughout the city was obtained from the limestone Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines, which were owned by Ralph Allen (1694–1764).[45] Allen, in order to advertise the quality of his quarried limestone, commissioned the elder John Wood to build him a country house on his Prior Park estate between the city and the mines.[45] He was also responsible for improving and expanding the postal service in western England, for which he held the contract for over forty years.[45] Though not fond of politics, Allen was a civic-minded man, and served as a member of the Bath Corporation for many years. He was elected Mayor of the city for a single term, in 1742, at age 50.[45]

The early 18th century saw Bath acquire its first purpose-built theatre, the Old Orchard Street Theatre, which was rebuilt as the Theatre Royal, the along with the Grand Pump Room attached to the Roman Baths and assembly rooms. Master of Ceremonies Beau Nash, who presided over the city's social life from 1705 until his death in 1761, drew up a code of behaviour for public entertainments.[46]

Late Modern

The population of the city had reached 40,020 by the time of the 1801 census, making it one of the largest cities in Britain.[47] William Thomas Beckford bought a house in Lansdown Crescent in 1822, eventually buying a further two houses in the crescent to form his residence. Having acquired all the land between his home and the top of Lansdown Hill, he created a garden over half a mile in length and built Beckford's Tower at the top.[48]

Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia spent the four years of his exile, from 1936 to 1940, at Fairfield House in Bath.[49] During World War II, between the evening of 25 April and the early morning of 27 April 1942, Bath suffered three air raids in reprisal for RAF raids on the German cities of Lübeck and Rostock, part of the Luftwaffe campaign popularly known as the Baedeker Blitz. Over 400 people were killed, and more than 19,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed.[50] Houses in the Royal Crescent, Circus and Paragon were burnt out along with the Assembly Rooms, while part of the south side of Queen Square was destroyed.[51]

A postwar review of inadequate housing led to the clearance and redevelopment of areas of the city in a postwar style, often at variance with the local Georgian style. In the 1950s the nearby villages of Combe Down, Twerton and Weston were incorporated into Bath to enable the development of further housing, much of it council housing. In the 1970s and 1980s it was recognised that conservation of historic buildings was inadequate, leading to more care and reuse of buildings and open spaces.[52] In 1987 the city was selected by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, recognising its international cultural significance.[53]

Since 2000, developments have included the Bath Spa, SouthGate and the Bath Western Riverside project.[54]

Governance

Historically part of the county of Somerset, Bath was made a county borough in 1889 and hence independent of the newly created administrative Somerset county council.[55] Bath became part of Avon when that non-metropolitan county was created in 1974. Since the abolition of Avon in 1996, Bath has been the main centre of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset (B&NES).[56] Bath remains, however, in the ceremonial county of Somerset, though not within the administrative non-metropolitan county of Somerset.

Because Bath is unparished, there is no longer a city council or parish council in the city. The City of Bath's ceremonial functions, including the mayoralty – which can be traced back to 1230 – and control of the coat of arms, are now maintained by the Charter Trustees of the City of Bath.[57] The coat of arms includes two silver strips, which represent the River Avon and the hot springs. The sword of St. Paul is a link to Bath Abbey. The supporters, a lion and a bear, stand on a bed of acorns, a link to Bladud, the subject of the Legend of Bath. The knight's helmet indicates a municipality and the crown is that of King Edgar.[58]

Before the Reform Act 1832 Bath elected two members to the unreformed House of Commons.[59] Bath now has a single parliamentary constituency, with Liberal Democrat Don Foster as Member of Parliament (1992– ). His election was a notable result of the 1992 general election, as Chris Patten, the previous Member (and a Cabinet Minister) played a major part, as Chairman of the Conservative Party, in getting the government of John Major re-elected, but failed to defend his marginal seat in Bath. Don Foster has been re-elected as the MP for Bath in every election since. As of 2010, his majority stands at 11883.[60]

The electoral wards of the Bath and North East Somerset unitary authority within Bath are the central Abbey, Kingsmead and Walcot wards, and the more outlying Bathwick, Combe Down, Lambridge, Lansdown, Lyncombe, Newbridge, Odd Down, Oldfield, Southdown, Twerton, Westmoreland, Weston and Widcombe wards.[61]

Geography

Physical geography

Bath is at the bottom of the Avon Valley, and near the southern edge of the Cotswolds, a range of limestone hills designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The hills that surround and make up the city have a maximum altitude of 238 metres (781 ft) on the Lansdown plateau. Bath has an area of 29 square kilometres (11 sq mi).[62]

The surrounding hills give Bath its steep streets and make its buildings appear to climb the slopes. The flood plain of the River Avon, which runs through the centre of the city, has an altitude of about 18 metres (59 ft) above sea level.[63] The river, once an unnavigable series of braided streams broken up by swamps and ponds, has been managed by weirs into a single channel. Nevertheless, periodic flooding, which shortened the life of many buildings in the lowest part of the city, was normal until major flood control works in the 1970s.[64]

The water which bubbles up from the ground, as geothermal springs, previously fell as rain on the Mendip Hills. It percolates down through limestone aquifers to a depth of between 2,700 and 4,300 metres (c. 9,000–14,000 ft) where geothermal energy raises the water temperature to between 64 and 96 °C (c. 147–205 °F). Under pressure, the heated water rises to the surface along fissures and faults in the limestone. This process is similar to an artificial one known as Enhanced Geothermal System which also makes use of the high pressures and temperatures below the Earth's crust. Hot water at a temperature of 46 °C (115 °F) rises here at the rate of 1,170,000 litres (257,364 imp gal) every day,[65] from a geological fault (the Pennyquick fault). In 1983, a new spa water bore-hole was sunk, providing a clean and safe supply of spa water for drinking in the Pump Room.[66] There is no universal definition to distinguish a hot spring from another geothermal spring, though by several definitions, the Bath springs can be considered the only hot springs in the UK. Three of these springs feed the thermal baths.

Climate

Along with the rest of South West England, Bath has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of the country.[67] The annual mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50.0 °F). Seasonal temperature variation is less extreme than most of the United Kingdom because of the adjacent sea temperatures. The summer months of July and August are the warmest with mean daily maxima of approximately 21 °C (69.8 °F). In winter mean minimum temperatures of 1 °C (33.8 °F) or 2 °C (35.6 °F) are common.[67] In the summer the Azores high pressure affects the south-west of England, however convective cloud sometimes forms inland, reducing the number of hours of sunshine. Annual sunshine rates are slightly less than the regional average of 1,600 hours.[67] In December 1998 there were 20 days without sun recorded at Yeovilton. Most the rainfall in the south-west is caused by Atlantic depressions or by convection. Most of the rainfall in autumn and winter is caused by the Atlantic depressions, which is when they are most active. In summer, a large proportion of the rainfall is caused by sun heating the ground leading to convection and to showers and thunderstorms. Average rainfall is around 700 mm (28 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August have the lightest winds. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.[67]

Yeovilton climate: Average maximum and minimum temperatures, and average rainfall recorded between 1971 and 2000 by the Met Office. Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Average max. temperature °C (°F) 8.1

(46.6)8.3

(46.9)10.6

(51.1)12.9

(55.2)16.5

(61.7)19.3

(66.7)21.7

(71.1)21.5

(70.7)18.6

(65.5)14.8

(58.6)11.1

(52.0)9.0

(48.2)14.4

(57.9)Average min. temperature

°C (°F)1.4

(34.5)1.3

(34.3)2.7

(36.9)3.7

(38.7)6.8

(44.2)9.7

(49.5)11.9

(53.4)11.7

(53.1)9.6

(49.3)6.9

(44.4)3.6

(38.5)2.4

(36.3)6.0

(42.8)Rainfall

mm(inches)72.0

(2.84)55.6

(2.19)56.6

(2.23)47.3

(1.86)48.9

(1.93)57.2

(2.25)48.9

(1.93)56.6

(2.23)64.5

(2.54)67.9

(2.67)65.8

(2.59)83.3

(3.28)724.5

(28.52)Source: Met Office Demography

As of 2001 the city of Bath has a population of 83,992.[1] According to the UK Government's 2001 census, Bath, together with North East Somerset, which includes areas around Bath as far as the Chew Valley, has a population of 169,040, with an average age of 39.9 (the national average being 38.6). Demographics shows according to the same statistics, the district is overwhelmingly populated by people of a white ethnic background at 97.2% – significantly higher than the national average of 90.9%. Other ethnic groups in the district, in order of population size, are multiracial at 1%, Asian at 0.5% and black at 0.5% (the national averages are 1.3%, 4.6% and 2.1%, respectively).[68]

The district is largely Christian at 71%, with no other religion reaching more than 0.5%. These figures generally compare with the national averages, though the non-religious, at 19.5%, are significantly more prevalent than the national 14.8%. 7.4% of the population describe themselves as "not healthy" in the last 12 months, compared with a national average of 9.2%; nationally 18.2% of people describe themselves as having a long-term illness, in Bath it is 15.8%.[68]

Culture

Bath became the leading centre of fashionable life in England during the 18th century. It was during this time that Bath's Old Orchard Street Theatre was built, as well as architectural developments such as Lansdown Crescent,[69] the Royal Crescent,[70] The Circus and Pulteney Bridge.[71]

Today, Bath has five theatres – Bath Theatre Royal, Ustinov Studio, the egg, the Rondo Theatre, and the Mission Theatre – and attracts internationally renowned companies and directors, including an annual season by Sir Peter Hall. The city also has a long-standing musical tradition; Bath Abbey is home to the Klais Organ and is the largest concert venue in the city,[72] with about 20 concerts and 26 organ recitals each year. Another important concert venue is the Forum, a 1,700-seat art deco building which originated as a cinema. The city holds the Bath International Music Festival and Mozartfest every year. Other festivals include the annual Bath Film Festival, Bath Literature Festival (and its counterpart for children), the Bath Fringe Festival and the Bath Beer Festival, and the Bach Festivals which occur at two and a half year intervals. An annual competition for the Bard of Bath aims to find Bath's best poet, singer or storyteller. The Bard uses the title to develop artistic projects in the area and leads evening bardic walks around the city. The title resurrects an Iron-Age Celtic Druid tradition where Druids were the law-makers, judges and ceremonial leaders, Ovates were mediums, healers and prophets and Bards were poets, musicians and history-keepers. All of them held high status and a place in mystical/religious circles.[73]

The city is home to the Victoria Art Gallery,[74] the Museum of East Asian Art, and Holburne Museum of Art,[75] numerous commercial art galleries and antique shops, as well as numerous museums, among them Bath Postal Museum, the Fashion Museum, the Jane Austen Centre, the Herschel Museum of Astronomy and the Roman Baths.[76] The Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution, now in Queen Square, and founded in 1824 on the base of a 1777 Society for the encouragement of Agriculture, Planting, Manufactures, Commerce and the Fine Arts, has an important collection and holds a programme of talks and discussions.

Bath in the arts

Two of 104 decorated pigs on display in the city. This was a public art event, called "King Bladud's Pigs in Bath" celebrating the city, its origins and its artists. Decorated pig sculptures were on display throughout the summer of 2008, to be later auctioned to raise funds for Bath's Two Tunnels Greenway.

Two of 104 decorated pigs on display in the city. This was a public art event, called "King Bladud's Pigs in Bath" celebrating the city, its origins and its artists. Decorated pig sculptures were on display throughout the summer of 2008, to be later auctioned to raise funds for Bath's Two Tunnels Greenway.

During the 18th century Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Thomas Lawrence lived and worked in Bath.[77][78] John Maggs, a painter best known for his coaching scenes, was born and lived in Bath with his artistic family.[79] William Friese-Greene began experimenting with celluloid and motion pictures in his studio in Bath in the 1870s, developing some of the earliest movie camera technology there. He is credited as the inventor of cinematography.[80]

Jane Austen lived in the city from 1801 with her father, mother and sister Cassandra, and the family resided in the city at four successive addresses until 1806.[81] However, Jane Austen never liked the city, and wrote to her sister Cassandra, "It will be two years tomorrow since we left Bath for Clifton, with what happy feelings of escape."[82] Despite these feelings, Bath has honoured her name with the Jane Austen Centre and a city walk. Austen's later Northanger Abbey and Persuasion are largely set in the city and feature descriptions of taking the waters, social life, and music recitals. Taking the waters is also described in Charles Dickens' novel The Pickwick Papers in which Pickwick's servant, Sam Weller, comments that the water has "a very strong flavour o' warm flat irons", while the Royal Crescent is the venue for a chase between two of the characters, Dowler and Winkle.[83] Moyra Caldecott's novel The Waters of Sul is set in Roman Bath in 72 AD. Richard Brinsley Sheridan's play The Rivals takes place in the city,[84] as does Roald Dahl's chilling short-story, The Landlady.[85]

Many films and television programmes have been filmed using the architecture of Bath as the backdrop including: the 2004 film of Thackeray's Vanity Fair,[86] The Duchess (2008),[86] The Elusive Pimpernel (1950)[86] and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).[86]

In August 2003 the Three Tenors sang at a special concert to mark the opening of the Thermae Bath Spa, a new hot water spa in Bath City Centre; delays to the project meant the spa actually opened three years later on 7 August 2006.

Parks

The city has several public parks, the main one being Royal Victoria Park, which is a short walk from the centre of the city. It was opened in 1830 by an 11-year-old Princess Victoria, and was the first park to carry her name.[87] The park is overlooked by the Royal Crescent and is 23 hectares (57 acres) in area.[88] It has a variety of attractions.[88] including a skateboard ramp, tennis courts, bowling, a putting green and a 12- and 18-hole golf course, a pond, open air concerts, and a popular children's play area. Much of its area is lawn; a notable feature is the way in which a ha-ha segregates it from the Royal Crescent, while giving the impression to a viewer from the Crescent of a greensward uninterrupted across the Park down to Royal Avenue. It has received a "Green Flag award", the national standard for parks and green spaces in England and Wales, and is registered by English Heritage as a Park of National Historic Importance.[89] The 3.84 hectares (9.5 acres) botanical gardens were formed in 1887 and contain one of the finest collections of plants on limestone in the West Country.[90] The replica of a Roman Temple was used at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924.[91] In 1987 the gardens were extended to include the Great Dell, a disused quarry that was formally part of the park, which contains a large collection of conifers.

Other parks in Bath include: Alexandra Park, which crowns a hill and overlooks the city; Parade Gardens, along the river front near the Abbey in the centre of the city; Sydney Gardens, known as a pleasure-garden in the 18th century; Henrietta Park; Hedgemead Park; and Alice Park. Jane Austen wrote of Sydney Gardens that "It would be pleasant to be near the Sydney Gardens. We could go into the Labyrinth every day."[92] Alexandra, Alice and Henrietta parks were built into the growing city among the housing developments.[93] There is also a linear park following the old Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway line, and, in a green area adjoining the River Avon, Cleveland Pools were built around 1815.[94] It is now the oldest surviving public outdoor lido in England,[95] and plans have been submitted for its restoration.[96]

Food

Bath is linked to a variety of foods that are distinctive in their association with the city. The Sally Lunn buns (a type of teacake) have long been baked in Bath. They were first mentioned by that name in verses printed in a local newspaper, the Bath Chronicle, in 1772.[97] At that time they were eaten hot at public breakfasts in the city's Spring Gardens. They can be eaten with sweet or savoury toppings. These are sometimes confused with Bath buns which are smaller, round, very sweet, very rich buns that were associated with the city following The Great Exhibition. Bath buns were originally topped with crushed comfits created by dipping caraway seeds repeatedly in boiling sugar; but today seeds are added to a 'London Bath Bun' (a reference to the bun's promotion and sale at the Great Exhibition).[98] The seeds may be replaced by crushed sugar granules or 'nibs'.

Bath has also lent its name to one other distinctive recipe – Bath Olivers – the dry baked biscuit invented by Dr William Oliver, physician to the Mineral Water Hospital in 1740.[99] Oliver was an early anti-obesity campaigner and the author of a "Practical Essay on the Use and Abuse of warm Bathing in Gluty Cases".[99] In more recent years, Oliver's efforts have been traduced by the introduction of a version of the biscuit with a plain chocolate coating. The Bath Chap, which is the salted and smoked cheek and jawbones of the pig, takes its name from the city.[100] It is still available from a stall in the daily covered market. Although there is a brewery named Bath Ales, located a few miles away in Warmley, Abbey Ales are brewed in the city.[101]

Sport

Bath Rugby is a rugby union team which is currently in the Aviva Premiership league and coached by Steve Meehan.[102] It plays in black, blue and white kit at the Recreation Ground in the city, where it has been since the late 19th century, following its establishment in 1865.[103] The team's first major honour was winning the John Player Cup four years consecutively from 1984 until 1987.[104] The team then led the Courage league in six seasons in eight years between 1988/1989 and 1995/1996, during which time it also won the Pilkington Cup in 1989, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1995 and 1996.[104] It finally won the Heineken Cup in the 1997/1998 season, and topped the Zürich Premiership (now Guinness Premiership) in 2003–2004.[104] The team's current squad includes several members who also play in the English national team including: Lee Mears, David Flatman. Nick Abendanon and Matt Banahan. Colston's Collegiate School, Bristol has had a large input in the team over the past decade, providing several current 1st XV squad members. The former England Rugby Team Manager Andy Robinson used to play for Bath Rugby team and was captain and later coach. Both of Robinson's predecessors, Clive Woodward and Jack Rowell, were also former Bath coaches and managers as well as his successor Brian Ashton.

Bath City F.C. is the major football team. Bath City gained promotion to the Conference National from the Conference South in 2010. Bath City F.C. play their games at Twerton Park. Until 2009 Team Bath F.C. operated as an affiliate to the University Athletics programme. In 2002, Team Bath became the first university team to enter the FA Cup in 120 years, and advanced through four qualifying rounds to the first round proper.[105] The university's team was established in 1999, while the city team has existed since before 1908 (when it entered the Western League).[106] However in 2009, the Football Conference ruled that Team Bath would not be eligible to gain promotion to a National division, nor were they allowed to participate in Football Association cup competitions. This ruling led to the decision by the club to fold at the end of the 2008/09 Conference South competition. In their final season, Team Bath F.C. finished a respectable 11th in the league.

Bath City narrowly missed out on election to the Football League in 1985.

Many cricket clubs are based in the city, including Bath Cricket Club, who are based at the North Parade Ground and play in the West of England Premier League. Cricket is also played on the Recreation Ground, just across from where the Rugby is played. The Rec's cricket ground is the venue for the annual Bath Cricket Festival which sees Somerset County Cricket Club play several games. The Recreation Ground is also home to Bath Croquet Club, which was re-formed in 1976 and is affiliated with the South West Federation of Croquet Clubs.[107]

The Bath Half Marathon is run annually through the city streets, with over 10,000 runners.[108] Bath also has a thriving cycling community, with places for biking including Royal Victoria Park, 'The Tumps' in Odd Down/east, the jumps on top of Lansdown, and Prior Park. Places for biking near Bath include Brown's Folly in Batheaston and Box Woods, in Box.

TeamBath is the umbrella name for all of the University of Bath sports teams, including the aforementioned football club. Other sports for which TeamBath is noted are athletics, badminton, basketball, bob skeleton, bobsleigh, hockey, judo, modern pentathlon, netball, rugby union, swimming, tennis, triathlon and volleyball. The City of Bath Triathlon takes place annually at the university.

Industry

Bath once had an important manufacturing sector, led by companies such Stothert and Pitt. Nowadays manufacturing is in decline in the city, but it boasts strong software, publishing and service-oriented industries, being home to companies such as Future Publishing and London & Country mortgage brokers. The city's attraction to tourists has also led to a significant number of jobs in tourism-related industries. Important economic sectors in Bath include education and health (30,000 jobs), retail, tourism and leisure (14,000 jobs) and business and professional services (10,000 jobs).[6] Its main employers are the National Health Service, the two universities and the Bath and North East Somerset Council, as well as the Ministry of Defence, although a number of MOD offices formerly in Bath have now moved to Bristol. Growing employment sectors include information and communication technologies and creative and cultural industries where Bath is one of the recognised national centres for publishing,[6] with the magazine publisher Future Publishing employing around 650 people. Others include Buro Happold (400) and IPL Information Processing Limited (250).[109] The city contains over 400 retail shops, 50% being run by independent specialist retailers, and around 100 restaurants and cafes which are primarily supported by tourism.[6]

Tourism

Bath is popular with tourists all year round. The entertainer is performing in front of Bath Abbey; the Roman Baths are to the right.

Bath is popular with tourists all year round. The entertainer is performing in front of Bath Abbey; the Roman Baths are to the right.

One of Bath's principal industries is tourism, with more than one million staying visitors and 3.8 million day visitors to the city on an annual basis.[6] The visits mainly fall into the categories of heritage tourism and cultural tourism, aided by the city's selection in 1987 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognising its international cultural significance.[52] All significant stages of the history of England are represented within the city, from the Roman Baths (including their significant Celtic presence), to Bath Abbey and the Royal Crescent, to Thermae Bath Spa in the 2000s. The size of the tourist industry is reflected in the almost 300 places of accommodation – including over 80 hotels, and over 180 bed and breakfasts – many of which are located in Georgian buildings. The history of the city is displayed at the Building of Bath Collection which is housed in a building which was built in 1765 as the Trinity Presbyterian Church. It was also known as the Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel, as she lived in the attached house from 1707 to 1791.[110] Two of the hotels have 'five-star' ratings.[111] There are also two campsites located on the western edge of the city. The city also contains about 100 restaurants, and a similar number of public houses and bars. Several companies offer open-top bus tours around the city, as well as tours on foot and on the river. Since 2006, with the opening of Thermae Bath Spa, the city has attempted to recapture its historical position as the only town in the United Kingdom offering visitors the opportunity to bathe in naturally heated spring waters.

In the 2010 Google Street View Best Streets Awards, the Royal Crescent took the second place in the "Britain's Most Picturesque Street" award, first place being given to The Shambles in York. Milsom Street was also awarded "Britain's Best Fashion Street" in the 11,000 strong vote.[112][113]

Twinning

Bath is twinned with five other cities a partnership agreement with Manly, New South Wales, Australia.[114]

- Aix-en-Provence, France

- Alkmaar, Netherlands

- Braunschweig, Germany

- Kaposvár, Hungary

- Beppu, Ōita Prefecture, Japan

Transport

Bath is approximately 13 miles (21 km) south-east of the larger city and port of Bristol, to which it is linked by the A4 road, and is a similar distance south of the M4 motorway. In an attempt to reduce the level of car use Park and Ride schemes have been introduced, with sites at Odd Down, Lansdown and Newbridge, with a Saturdays-only site at the University of Bath. In addition a Bus Gate scheme in Northgate aims to reduce private car use in the city centre.[115] National Express operates coach services from Bath Bus Station to a number of cities. Internally, Bath has a network of bus routes run by First Group, with services to surrounding towns and cities. There is one other company running open top double-decker bus tours around the city.

The city is connected to Bristol and the sea by the River Avon, navigable via locks by small boats. The river was connected to the River Thames and London by the Kennet and Avon Canal in 1810 via Bath Locks; this waterway – closed for many years, but restored in the last years of the 20th century – is now popular with narrowboat users.[116] Bath is on National Cycle Route 4, with one of Britain's first cycleways, the Bristol & Bath Railway Path, to the west, and an eastern route toward London on the canal towpath. Bath is about 18 miles (29 km) from Bristol Airport.

Bath is served by the Bath Spa railway station (designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel), which has regular connections to London Paddington, Bristol Temple Meads, Cardiff Central, Exeter, Plymouth and Penzance (see Great Western Main Line), and also Westbury, Warminster, Salisbury, Southampton, Portsmouth and Brighton (see Wessex Main Line). Services are provided by First Great Western. There is a suburban station on the main line, Oldfield Park, which has a limited commuter service to Bristol as well as other destinations. Green Park Station was once the terminus of the Midland Railway,[117] and junction for the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, whose line, always steam hauled, went under Bear Flat through the Combe Down Tunnel and climbed over the Mendips to serve many towns and villages on its 71-mile (114 km) run to Bournemouth. This example of an English rural line was closed by Beeching in March 1966. Its Bath station building, now restored, houses shops, small businesses, the Saturday Bath Farmers Market and parking for a supermarket, while the route of the Somerset and Dorset within Bath is to be reused for the Two Tunnels Greenway, a shared use path that will extend National Cycle Route 24 into the city.

A tram system was introduced in the late 19th century opening on 24 December 1880. The 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge cars were horse-drawn along a route from London Road to the Bath Spa railway station, but the system closed in 1902. It was replaced by electric tram cars on a greatly expanded 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) gauge system that opened in 1904. This eventually extended to 18 miles (29 km) with routes to Combe Down, Oldfield Park, Twerton, Newton St Loe, Weston and Bathford. There was a fleet of 40 cars, all but 6 being double deck. The first line to close was replaced by a bus service in 1938, and the last went on 6 May 1939.[118]

Architecture

Main article: Buildings and architecture of BathCity of Bath * UNESCO World Heritage Site

Country United Kingdom Type Cultural Criteria i, ii, iv Reference 428 Region ** Europe and North America Inscription history Inscription 1987 (11th Session) * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List

** Region as classified by UNESCOThere are many Roman archaeological sites throughout the central area of the city, but the baths themselves are about 6 metres (20 ft) below the present city street level. Around the hot springs, Roman foundations, pillar bases, and baths can still be seen, however all the stonework above the level of the baths is from more recent periods.[119]

Bath Abbey was a Norman church built on earlier foundations, although the present building dates from the early 16th century and shows a late Perpendicular style with flying buttresses and crocketed pinnacles decorating a crenellated and pierced parapet.[120] The choir and transepts have a fan vault by Robert and William Vertue.[121] The nave was given a matching vault in the 19th century.[122] The building is lit by 52 windows.[123]

Most buildings in Bath are made from the local, golden-coloured Bath Stone, and many date from the 18th and 19th century. The dominant style of architecture in Central Bath is Georgian;[124] this evolved from the Palladian revival style which became popular in the early 18th century. Many of the prominent architects of the day were employed in the development of the city. The original purpose of much of Bath's architecture is concealed by the honey-coloured classical façades; in an era before the advent of the luxury hotel, these apparently elegant residences were frequently purpose-built lodging houses, where visitors could hire a room, a floor, or (according to their means) an entire house for the duration of their visit, and be waited on by the house's communal servants.[125] The masons Reeves of Bath were prominent in the city from the 1770s to 1860s.

"The Circus" consists of three long, curved terraces designed by the elder John Wood to form a circular space or theatre intended for civic functions and games. The games give a clue to the design, the inspiration behind which was the Colosseum in Rome.[126] Like the Colosseum, the three façades have a different order of architecture on each floor: Doric on the ground level, then Ionic on the piano nobile and finishing with Corinthian on the upper floor, the style of the building thus becoming progressively more ornate as it rises.[126] Wood never lived to see his unique example of town planning completed, as he died five days after personally laying the foundation stone on 18 May 1754.[126]

Fan vaulting over the nave at Bath Abbey, Bath, England. Made from local Bath stone, this is a Victorian restoration (made in the 1860s) of the original roof from 1608

Fan vaulting over the nave at Bath Abbey, Bath, England. Made from local Bath stone, this is a Victorian restoration (made in the 1860s) of the original roof from 1608

The most spectacular of Bath's terraces is the Royal Crescent, built between 1767 and 1774 and designed by the younger John Wood.[127] But all is not what it seems; while Wood designed the great curved façade of what appears to be about 30 houses with Ionic columns on a rusticated ground floor, that was the extent of his input. Each purchaser bought a certain length of the façade, and then employed their own architect to build a house to their own specifications behind it; hence what appears to be two houses is sometimes one. This system of town planning is betrayed at the rear of the crescent: while the front is completely uniform and symmetrical, the rear is a mixture of differing roof heights, juxtapositions and fenestration. This "Queen Anne fronts and Mary-Anne backs" architecture occurs repeatedly in Bath.[128] Other fine terraces elsewhere in the city include Lansdown Crescent and Somerset Place on the northern hill.

Around 1770 the neoclassical architect Robert Adam designed Pulteney Bridge, using as the prototype for the three-arched bridge spanning the Avon an original, but unused, design by Palladio for the Rialto Bridge in Venice.[129] Thus, Pulteney Bridge became not just a means of crossing the river, but also a shopping arcade. Along with the Rialto Bridge, is one of the very few surviving bridges in Europe to serve this dual purpose.[129] It has been substantially altered since it was built. The bridge was named after Frances and William Pulteney, the owners of the Bathwick estate for which the bridge provided a link to the rest of Bath.[129]

The heart of the Georgian city was the Pump Room, which, together with its associated Lower Assembly Rooms, was designed by Thomas Baldwin, a local builder responsible for many other buildings in the city, including the terraces in Argyle Street,[130] and the Guildhall.[131] Baldwin rose rapidly, becoming a leader in Bath's architectural history. In 1776 he was made the chief City Surveyor, and in 1780 became Bath City Architect.[130] Great Pulteney Street, where he eventually lived, is another of his works: this wide boulevard, constructed circa 1789 and over 1,000 feet (305 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide, is lined on both sides by Georgian terraces.

In the 1960s and early 1970s some parts of Bath were unsympathetically redeveloped, resulting in the loss of some 18th- and 19th-century buildings. This process was largely halted by a popular campaign which drew strength from the publication of Adam Fergusson's The Sack of Bath.[132] Controversy has revived perodically, most recently with the demolition of the 1930s Churchill House, a neo-Georgian municipal building originally housing the Electricity Board, to make way for a new bus station. This is part of the Southgate redevelopment in which an ill-favoured 1960s shopping precinct, bus station and multi-story car park were demolished and replaced by a new area of mock-Georgian shopping streets.[133][134] As a result of this and other changes, notably plans for abandoned industrial land along the Avon, the city's status as a World Heritage Site was reviewed by UNESCO in 2009.[135] The decision was made let Bath keep its status, but UNESCO has asked to be consulted on future phases of the Riverside development,[136] saying that the density and volume of buildings in the second and third phases of the development need to be reconsidered.[137] It also demands that Bath do more to attract world-class architecture in new developments.[137]

Education

Bath has two universities. The University of Bath was established in 1966.[138] The university was named University of the Year by the Sunday Times (2011) and is known, academically, for the physical sciences, mathematics, architecture, management and technology.[139]

Bath Spa University was first granted degree-awarding powers in 1992 as a university college, before being granted university status in August 2005.[140] It has schools in the following subject areas: Art and Design, Education, English and Creative Studies, Historical and Cultural Studies, Music and the Performing Arts, Science and the Environment and Social Sciences.[140]

The city contains one further education college, City of Bath College, and several sixth forms as part of both state and independent schools.

Bath is also home to Norland College, a provider of childcare training and education.

Media

Bath has two main local newspapers, the Bath Chronicle and the Bath Times. The Bath Chronicle, published since 1760, was a daily newspaper until mid-September 2007, when it became a weekly.[141] The Bath Times is a free weekly newspaper, largely based on advertising. Both newspapers are owned by Northcliffe Media.

The BBC's Where I Live website for Somerset has featured coverage of news and events within Bath since 2003.[142]

For television, Bath is served by the BBC West studios based in Bristol, and by ITV West (formerly HTV) with studios similarly in Bristol.

Radio stations broadcasting to the city include TotalStar Bath and Heart Bath as well as The University of Bath's 1449AM URB, a student-focused radio station available on campus and also online,[143] and Classic Gold 1260 a networked commercial radio station with local programmes.

See also

- List of people from Bath

- List of Grade I listed buildings in Bath and North East Somerset

- List of spa towns in the United Kingdom

- Batman rapist

References

- ^ a b c "Population Statistics". Bath and North East Somerset District Council. http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/councilanddemocracy/statisticsandcensusinformation/Pages/default.aspx. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Civic Insignia". City of Bath. http://www.thecityofbath.co.uk/civic_insignia.htm. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "History of Bath's Spa". Bath Tourism Plus. http://visitbath.co.uk/site/spa-and-wellbeing/history-of-baths-spa. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ a b "City of Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan". Bath and North East Somerset. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070614100836/http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/worldheritage/2.3Des.htm. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Edgar the Peaceful". English Monarchs – Kings and Queens of England. http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/saxon_12.htm. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Bath in Focus". Business Matters. http://www.business-matters.biz/site.aspx?i=pg64. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ Wessex Archaeology. "Archaeological Desk- based Assessment". University Of Bath, Masterplan Development Proposal 2008. Bath University. http://www.bath.ac.uk/masterplan/documents/AppendixF.pdf.

- ^ "Monument No. 204162". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=204162. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. p. 21. ISBN 9780948975868.

- ^ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 46–48. ISBN 9780948975868.

- ^ "Bathampton Camp". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=203244. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "The Beaker people and the Bronze Age". Somerset County Council. http://www1.somerset.gov.uk/archives/ASH/Beakpeop.htm. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ a b "The Roman Baths". Somerset Tourist Guide. http://www.somersettouristguide.com/Bath/The_Roman_Baths_722.asp. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ A L Rowse, Heritage of Britain, 1995, Treasure of London, ISBN 978-0-907407-58-4, 184 pages, Page 15

- ^ "A Corpus of Writing-Tablets from Roman Britain". Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Oxford. http://www.csad.ox.ac.uk/RIB/RIBIV/jp4.htm. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "The History of Plumbing — Roman and English Legacy". Plumbing World. http://www.plumbingworld.com/historyroman.html. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "The Roman Baths". TimeTravel Britain. http://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/stones/romanbaths.shtml. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Alfreds Borough". Bath Past. http://www.buildinghistory.org/bath/saxon/alfredsborough.shtml. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "The Roman Baths". BirminghamUk.com. http://www.birminghamuk.com/romanbaths.htm. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Dobunni to Hwicce". Bath past. http://www.buildinghistory.org/bath/saxon/dobunni.shtml#Gildas. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ a b "History of bath england, roman bath history". My England Travel Guide. http://www.myenglandtravel.com/history-of-bath-england.html. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Klinck, Anne (1992). The Old English Elegies: A Critical Edition and Genre Study. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 61.

- ^ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 31-34. ISBN 075241965x.

- ^ "Timeline Bath". Time Travel Britain. http://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/bathtime.shtml. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Saint David". 100 Welsh Heroes. http://www.100welshheroes.com/en/biography/saint%20david. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Campbell et al., The Anglo-Saxons, pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Robert Poliquin's Music and Musicians. Quebec University. http://www.uquebec.ca/musique/orgues/angleterre/batha.html#English. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "Alfreds Borough". Bath Past. http://www.buildinghistory.org/bath/saxon/alfredsborough.shtml. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 40-42. ISBN 075241965x.

- ^ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 50-51. ISBN 075241965x.

- ^ a b Powicke, Maurice (1939). Handbook of British Chronology. ISBN 978-0-901050-17-5.

- ^ Barlow, Frank (March 2000). William Rufus. Yale University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-300-08291-3.

- ^ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. p. 71. ISBN 075241965x.

- ^ Huscroft Ruling England p. 128

- ^ "The eight-hundred-year story of St John's Hospital, Bath". Spirit of Care. Jean Manco. http://www.buildinghistory.org/jean/spiritofcare.shtml. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Manco, Jean. "Shelter in old age". Bath Past. http://www.buildinghistory.org/bath/medieval/shelter.shtml. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 97-98. ISBN 075241965x.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Visit Bath. http://visitbath.co.uk/site/things_to_do/p_24001. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "Renaissance Bath". City of Bath. http://www.thecityofbath.co.uk/renaissance_bath.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ A tour through the whole island of Great Britain; Divided into Journeys. Interspersed with Useful Observations; Particularly Calculated for the Use of Those who are Desirous of Travelling over England & Scotland. 2. 1801. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7n5HAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA387.

- ^ Rodgers, Colonel H.C.B. (1968). Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars. Seeley Service & Co..

- ^ Burns, D. Thorburn (1981). "Thomas Guidott (1638–1705): Physician and Chymist, contributor to the analysis of mineral waters". Analytical Proceedings including Analytical Communications: Royal Society of Chemistry 18 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1039/AP9811800002. http://www.rsc.org/publishing/journals/article.asp?doi=AP9811800002. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ Hembury, Phylis May (1990). The English Spa, 1560–1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3391-5.

- ^ "John Wood and the Creation of Georgian Bath". Building of Bath Museum. http://www.bathmuseum.co.uk/biography.htm. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Ralph Allen Biography". Bath Postal Museum. http://www.bathpostalmuseum.co.uk/explore/biographies/ralphallen.html. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Eglin, John (2005). The Imaginary Autocrat: Beau Nash and the invention of Bath. Profile. ISBN 978-1-86197-302-3.

- ^ "A vision of Bath". Britain through time. http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit_page.jsp?u_id=10167607. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "Beckford's Tower & Mortuary Chapel, Lansdown Cemetery". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442844. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ "The Emperor Haile Selassie I in Bath 1936–1940". Anglo-Ethiopian Society. http://anglo-ethiopian.org/publications/articles.php?type=O&reference=publications/occasionalpapers/papers/haileselassiebath.php. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "History — Bath at War". Royal Crescent Society, Bath. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070519191111/http%3A//www.royalcrescentbath.com/HistoryBathatWar.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Royal Crescent History: The Day Bombs fell on Bath". Royal Crescent Society, Bath. Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080131165322/http%3A//www.royalcrescentbath.com/HistoryRoyalCrescent%25202.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Cultural and historical development of Bath". Bath City-Wide Character Appraisal. Bath & North East Somerset Council. 31 August 2005. http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/environmentandplanning/planning/localdevelopmentscheme/Pages/Bath%20CW%20CA%20-%20Cultural%20and%20historical%20development.aspx. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- ^ "Bath – World Heritage Site". Bath & North East Somerset Council. http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/environmentandplanning/worldheritagesite/Pages/default.aspx. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "South Gate Bath". Morley. http://www.southgatebath.com. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Keane, Patrick (1981). "An English County and Education: Somerset, 1889–1902". The English Historical Review 88 (347): 286–311. doi:10.1039/AP9811800002.

- ^ "The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995". HMSO. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si1995/Uksi_19950493_en_1.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "The History of the Mayoralty". City of Bath. http://www.thecityofbath.co.uk/the_history_of_the_mayoralty.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Arms of The City of Bath". The City of Bath. http://www.thecityofbath.co.uk/coat_of_arms.htm. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ "Parliamentary Constituencies in the unreformed House". United Kingdom Election Results. http://www.election.demon.co.uk/prereform.html. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath constituency". The Guardian. UK. http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/constituency/694/bath. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Elections — Ward Maps". Bath & North East Somerset Council. 31 August 2005. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080621225523/http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/BathNES/councilanddemocracy/councillorsdemocracyandelections/elections/wardmaps.htm. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "Published Contaminated Land Inspection of the area surrounding Bath". Bath and North East Somerset Council. http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/environmentandplanning/Pollution/contaminatedland/Pages/default2.aspx. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Bath Western Riverside Outline Planning Application Design Statement, April 2006, Section 2.0, Site Analysis

- ^ "Carr's Mill, Lower Bristol Road, Bath Flood Risk Assessment". Bath and North East Somerset. http://idox.bathnes.gov.uk/WAM/doc/BackGround%20Papers-212576.pdf?extension=.pdf&id=212576&location=VOLUME1&contentType=application/pdf&pageCount=1. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Sacred Spring". Roman Baths Museum Web Site. http://www.romanbaths.co.uk/index.cfm?fuseAction=SM.nav&UUID=F9F320C4-1A95-4C04-AC609094E5B5DFD3. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Hot Water". Roman Baths Museum Web Site. http://www.romanbaths.co.uk/index.cfm?fuseAction=SM.nav&UUID=4B6F21CE-7CF4-4283-AF5C03FB05527814. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d "South West England: climate". Met Office. http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/sw/. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Bath and North East Somerset UA 2001 Census". National Statistics. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/profiles/00ha.asp. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "1 to 20 Lansdown Crescent". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442760. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Royal Crescent". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=443488. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Pulteney Bridge". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=443316. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Abbey Church". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442109. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Bard of Bath". Bard of Bath. http://sites.google.com/site/bardofbath/. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "Victoria Art Gallery". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442375. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ "Holburne of Menstrie Museum". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=443742. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ "Roman Baths Treatment Centre". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442194. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ "Thomas Gainsborough". The Artchive. http://www.artchive.com/artchive/G/gainsborough.html. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Artists Illustrating Boys' Fashions: Sir Thomas Lawrence (England, 1769–1830):". Historical Boys Clothing. http://www.histclo.com/art/artist-law.html. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "John Maggs". Art History Club. http://www.arthistoryclub.com/art_history/John_Maggs. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "William Friese Greene". Whos Who of Victorian Cinema. http://www.victorian-cinema.net/friesegreene.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Jane Austen Centre". Jane Austen Centre. http://www.janeausten.co.uk/. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ David, David (1998). Jane Austen: A Life. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21606-8.

- ^ "The Pickwick Papers". Complete works of Charles Dickens. http://www.dickens-literature.com/The_Pickwick_Papers/. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "The Rivals: A synopsis of the play by Richard Brinsley Sheridan". Theatre History.com. http://www.theatrehistory.com/irish/rivals.html. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "The Landlady by Roald Dahl" (PDF). Teaching English. http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/try/britlit/landlady. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Titles with locations including Bath, Somerset". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/List?endings=on&&locations=Bath,%20Somerset,%20England,%20UK&&heading=18;with+locations+including;Bath,%20Somerset,%20England,%20UK. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "Visit Bath & Beyond"

- ^ a b "Victoria Park". City of Bath. http://www.cityofbath.co.uk/Parks_rec/vicpark.html. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Royal Victoria Park". Green Flag award. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080206023920/http://www.greenflagaward.org.uk/winners/GSP001022/. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- ^ measurement given in acres

- ^ "Playing in the park". BBC Bristol. http://www.bbc.co.uk/bristol/content/articles/2007/06/27/royal_victoria_park_feature.shtml. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ Hill, Constance (1901). Jane Austen: Her homes & her friends. John Lane. Dodley Head Ltd.

- ^ "Local parks and gardens". Avon Gardens Trust. http://avongardenstrust.50webs.com/index.html. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Cleveland Baths". Images of England. English Heritage. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=445855. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Heritage Open Days". Bath and North East Somerset Council. http://www.romanbaths.co.uk/pdf/Heritage%20Open%20Days%2009%20FINAL.pdf. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Introuction". Cleveland Pools Trust. http://www.clevelandpools.org.uk/index.php5?title=Introduction. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "History of Sally Lunn Cake". Whats cooking America. http://whatscookingamerica.net/History/Cakes/SallyLunnCake.htm. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (1999). Oxford Companion to Food p 114. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9.

- ^ a b "Dr William Oliver, Bath Oliver Biscuit Inventor". Cornwall calling. http://www.cornwall-calling.co.uk/famous-cornish-people/oliver.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath chap". A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition, Oxford University Press. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O39-Bathchap.html. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "About Abbey Ales". Abbey Ales. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080619050133/http%3A//www.abbeyales.co.uk/page.asp%3Fid%3Daboutus. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "Bath promote Meehan to head coach". BBC. 2 August 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/rugby_union/english/5237610.stm. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ^ "The story so far". Bath Rugby. http://www.bathrugby.com/history/club_history.php. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "The story so far". Bath Rugby. http://www.bathrugby.com/history/club_history.php. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Paul Tisdale". Team Bath. http://www.teambath.com/2006/11/paul-tisdale/. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Bath City". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071213221220/http%3A//www.fchd.info/BATHC.HTM. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath Croquet Club". Bath Croquet Club. http://www.bathcroquet.com. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath Half Marathon". http://www.runninghigh.co.uk/site.aspx?i=ho0. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Economic Profile" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset. http://www.business-matters.biz/site.aspx?i=pg46. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Trinity Presbyterian Church (Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel) and Chapel House, forecourt wall, gatepiers and gates". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/details/default.aspx?id=443914. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ "AA-listed five-star hotels". Caterer Search. http://www.caterersearch.com/Articles/2009/02/11/310563/aa-listed-five-star-hotels.html. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Google Street View Awards 2010". http://www.google.com/landing/beststreetsuk/index.html. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "The Shambles, York, named Britain's 'most picturesque'". BBC News. 8 March 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8554388.stm. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Town Twinning". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071027142443/http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/BathNES/leisureandculture/tourismandtravel/Twinning/. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath Transport Package — Major Scheme Bid". Bath and North East Somerset. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071027135101/http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/BathNES/transportandstreets/transportpolicy/plansandstrategies/bathpackage/. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Allsop, Niall (1987). The Kennet & Avon Canal. Bath: Millstream Book. ISBN 978-0-948975-15-8.

- ^ Bristol and Bath Railway Path : The Midland Railway Retrieved on 8 August 2009

- ^ Oppitz, Leslie (1990). Tramways Remembered: West and South West England. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-095-3.

- ^ "City of Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan — Appendix 3". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070804014112/http://www.bathnes.gov.uk/worldheritage/3Append.htm. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442109. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "A Building of Vertue". Bath Past. http://www.buildinghistory.org/bath/abbey/vertue.shtml. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Planet Ware. http://www.planetware.com/bath/bath-abbey-eng-av-baabb.htm. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "Bath Abbey". Sacred destinations. http://www.sacred-destinations.com/england/bath-abbey. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Georgian architecture". Essential Architecture.com. http://www.essential-architecture.com/STYLE/STY-E02.htm. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ David, Graham (2000). "Social Decline and Slum Conditions: Irish migrants in Bath's History". Bath History Vol VIII.

- ^ a b c Gadd, David (1987). Georgian Summer. Countryside Books.

- ^ "Royal Crescent". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=447275. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ Moon, Michael; Cathy N. Davidson (1995). Subjects and Citizens: Nation, Race, and Gender from Oroonoko to Anita Hill. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1539-1.

- ^ a b c Manco, Jean (1995). "Pulteney Bridge". Architectural History (SAHGB Publications Limited) 38: 129–145. doi:10.2307/1568625. JSTOR 1568625.

- ^ a b Colvin, Howard (1997). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07207-5.

- ^ "Guildhall". Images of England. English Heritage. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/Details/Default.aspx?id=442118. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Borsay, Peter (2000). The Image of Georgian Bath, 1700–2000: Towns, Heritage, and History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820265-3.

- ^ "SouthGate Official Website". http://www.southgatebath.com/. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Bath Heritage Watchdog". http://www.bathheritagewatchdog.org/churchill.htm. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (6 April 2009). "Will Bath lose its World Heritage status?". The Guardian (UK). http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/apr/06/bath-heritage-architecture. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ "Bath keeps world heritage status". BBC News. 25 June 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/somerset/8119528.stm. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ a b "UNESCO demand for enhanced protection of Bath's surrounding landscape 'urgent and timely', says Bath Preservation Trust" (PDF). Bath Preservation Trust. 25 June 2009. http://www.bath-preservation-trust.org.uk/index.php?s=file_download&id=118. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "History of the University". University of Bath. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071112054105/http://www.bath.ac.uk/internal/staff/intro/history.html. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ "Departments". University of Bath. http://www.bath.ac.uk/departments/. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Bath Spa University". Bath Spa University. http://www.bathspa.ac.uk/. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ Brook, Stephen (2 August 2007). "Bath daily goes weekly". The Guardian (UK). http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2007/aug/02/pressandpublishing2. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "BBC Somerset". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/somerset/. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ "University Radio Bath". University Radio Bath. http://www.1449urb.co.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

External links

Cities of the United Kingdom England Bath · Birmingham · Bradford · Brighton and Hove · Bristol · Cambridge · Canterbury · Carlisle · Chester · Chichester · Coventry · Derby · Durham · Ely · Exeter · Gloucester · Hereford · Kingston upon Hull · Lancaster · Leeds · Leicester · Lichfield · Lincoln · Liverpool · London · Manchester · Newcastle upon Tyne · Norwich · Nottingham · Oxford · Peterborough · Plymouth · Portsmouth · Preston · Ripon · St Albans · Salford · Salisbury · Sheffield · Southampton · Stoke-on-Trent · Sunderland · Truro · Wakefield · Wells · Westminster · Winchester · Wolverhampton · Worcester · York

Scotland Wales Northern Ireland Ceremonial county of Somerset Somerset Portal Unitary authorities Boroughs or districts Major settlements Axbridge • Bath • Bridgwater • Bruton • Burnham-on-Sea • Castle Cary • Chard • Clevedon • Crewkerne • Dulverton • Frome • Glastonbury • Highbridge • Ilminster • Keynsham • Langport • Midsomer Norton • Minehead • Nailsea • North Petherton • Portishead • Radstock • Shepton Mallet • Somerton • South Petherton • Taunton • Watchet • Wellington • Wells • Weston-super-Mare • Wincanton • Wiveliscombe • Yeovil

See also: List of civil parishes in SomersetRivers Alham • Aller • Avill • Avon • Axe (Bristol Channel) • Axe (Lyme Bay) • Badgworthy Water • Banwell • Barle • Brue • Cam Brook • Cary • Chew • East Lyn • Exe • Fivehead • Frome • Haddeo • Hoar Oak Water • Holford • Horner • Huntspill • Isle • Land Yeo • Mells • Midford Brook • Oare Water • Parret • Severn Estuary • Sheppey • Somer • Sowy • Tone • Washford • Wellow Brook • West Lyn • Whitelake • Yeo (Congresbury) • Yeo (South Somerset)Topics County Council • Culture of Somerset • Economy of Somerset • Geography of Somerset • Geology of Somerset • History of Somerset • Museums • Transport in Somerset

Geographic areas: Blackdown Hills • Brendon Hills • Chew Valley • Exmoor • Mendip Hills • Polden Hills • Quantock Hills • Somerset Levels • South West Coast Path • West Somerset Coast PathCategories:- Bath, Somerset

- Cities in South West England

- Spa towns in England

- Towns in Bath and North East Somerset

- World Heritage Sites in England

- Former non-metropolitan districts of Avon

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.