- Clint Eastwood

-

Clint Eastwood

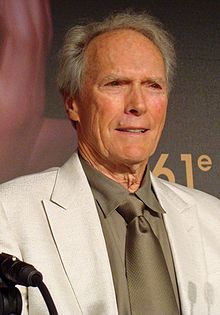

Eastwood at the 2010 Toronto International Film FestivalBorn Clinton Eastwood, Jr.

May 31, 1930

San Francisco, California, U.S.Nationality American Occupation Actor, director, producer, composer, politician Years active 1955–present Spouse Maggie Johnson (1953–84; two children)

Dina Ruiz (1996–present; one child)Children Kimber Tunis

Kyle Eastwood

Alison Eastwood

Scott Reeves

Kathryn Reeves

Francesca Fisher-Eastwood

Morgan Eastwood

This article is part of a series on

Clint EastwoodBackground · 1960s · 1970s · 1980s · 1990s · 2000s · Politics · Personal life · Awards and honors · Filmography · Discography · Malpaso Productions Clinton "Clint" Eastwood, Jr. (born May 31, 1930) is an American film actor, director, producer, composer and politician. Eastwood first came to prominence as a supporting cast member in the TV series Rawhide (1959–1965). He rose to fame for playing the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone's Dollars trilogy of spaghetti westerns (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) during the 1960s, and as San Francisco Police Department Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, Sudden Impact, and The Dead Pool) during the 1970s and 1980s. These roles, along with several others in which he plays tough-talking no-nonsense police officers, have made him an enduring cultural icon of masculinity.[1][2]

Eastwood won Academy Awards for Best Director and Producer of the Best Picture, as well as receiving nominations for Best Actor, for his work in the films Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). These films in particular, as well as others including Play Misty for Me (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Pale Rider (1985), In the Line of Fire (1993), The Bridges of Madison County (1995), and Gran Torino (2008), have all received commercial success and critical acclaim. Eastwood's only comedies have been Every Which Way but Loose (1978), its sequel Any Which Way You Can (1980), and Bronco Billy (1980); despite being widely panned by critics, the "Any Which Way" films are the two highest-grossing films of his career after adjusting for inflation.

Eastwood has directed most of his own star vehicles, but he has also directed films in which he did not appear such as Mystic River (2003) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), for which he received Academy Award nominations and Changeling (2008), which received Golden Globe Award nominations. He has received considerable critical praise in France in particular, including for several of his films which were panned in the United States, and was awarded two of France's highest honors: in 1994 he received the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres medal and in 2007 was awarded the Légion d'honneur medal. In 2000 he was awarded the Italian Venice Film Festival Golden Lion for lifetime achievement.

Since 1967, Eastwood has run his own production company, Malpaso, which has produced the vast majority of his films. He also served as the nonpartisan mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, from 1986 to 1988. Eastwood has seven children by five different women, and has married twice.

Contents

Early life

Main article: Early life and work of Clint EastwoodEastwood was born in San Francisco to Clinton Eastwood, Sr. (1906–70), a steelworker and migrant worker, and Margaret Ruth (née Runner; 1909–2006), a factory worker.[3] He was nicknamed "Samson" by the hospital nurses as he weighed 11 pounds 6 ounces (5.2 kg) at birth.[4][5][6] After his father died in 1970, Eastwood's mother remarried to John Belden Wood (1913–2004) in 1972, and they remained married until his death 32 years later.[7] Eastwood is of English, Irish, Scottish, and Dutch ancestry[3][8] and was raised in a middle class home with his younger sister, Jean (born 1934).[9][10] His family relocated often as his father worked at different jobs along the West Coast, including at a pulp mill.[11][12] The family settled in Piedmont, California, where Eastwood attended Piedmont Junior High School and Piedmont Senior High School, taking part in sports such as basketball, football, gymnastics, and competitive swimming.[13] He later transferred to Oakland Technical High School where the drama teachers encouraged him to enroll in school plays, but he was not interested. As his family moved to different areas he held a series of jobs including lifeguard, paper carrier, grocery clerk, forest firefighter, and golf caddy.[14]

In 1950, Eastwood began a one-year stint as a lifeguard for the United States Army during the Korean War[15] and was posted to Fort Ord in California.[16] While on leave in 1951 Eastwood was a passenger onboard a Douglas AD bomber that ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean near Point Reyes.[17][18] After escaping from the sinking aircraft he and the pilot swam 3 miles (5 km) to safety.[19]

Eastwood later moved to Los Angeles and began a romance with Maggie Johnson, a college student.[20] He managed an apartment house in Beverly Hills by day and worked at a gas station by night.[21] He enrolled at Los Angeles City College and married Johnson shortly before Christmas 1953 in South Pasadena.[21]

Film career

1950s

Main article: Clint Eastwood in the 1950sEarly career struggles

According to the CBS press release for Rawhide, Universal Studios, known then as the Universal-International film company, was shooting in Fort Ord when an enterprising assistant spotted Eastwood and arranged a meeting with the series' director.[22] According to Eastwood's official biography the key figure was a man named Chuck Hill, who was stationed in Fort Ord and had contacts in Hollywood.[22] Later, in Los Angeles, Hill became reacquainted with Eastwood and managed to sneak him into one of Universal's studios, where he showed him to cameraman Irving Glassberg.[22] Glassberg arranged for an audition with Arthur Lubin who, although impressed with Eastwood's appearance and 6-foot-4-inch (1.93 m) frame,[23] initially questioned his acting skills remarking, "He was quite amateurish. He didn't know which way to turn or which way to go or do anything".[24] Lubin suggested he attend drama classes and arranged for his initial contract in April 1954 at $100 (US$817 in 2011 dollars[25]) per week.[24] After signing Eastwood was initially criticized for his stiff manner, his squint and with hissing his lines through his teeth, a feature that would become a life-long trademark.[26][27][28][29]

In May 1954 Eastwood auditioned for his first role in Six Bridges to Cross, but was rejected by Joseph Pevney.[30] After many unsuccessful auditions he eventually landed a minor role as a laboratory assistant in director Jack Arnold's Revenge of the Creature, a sequel to The Creature from the Black Lagoon.[31] He then worked for three weeks on Lubin's Lady Godiva of Coventry in September 1954, then won a role in February 1955 as a sailor in Francis in the Navy as well as appearing uncredited in another Jack Arnold film, Tarantula, in which he played a squadron pilot.[32][33] In May 1955 Eastwood had a brief appearance in the film Never Say Goodbye, during which he shared a scene with Rock Hudson.[34] Universal presented him with his first television role on July 2, 1955, in NBC's Allen in Movieland, which starred Tony Curtis and Benny Goodman.[35] Although he continued to develop as an actor Universal terminated Eastwood's contract on October 23, 1955.[36][37]

Eastwood then joined the Marsh Agency and although Lubin landed him his biggest role to date in The First Traveling Saleslady (1956) and later hired him for Escapade in Japan, without a formal contract Eastwood struggled.[38] He met financial advisor Irving Leonard, who would later arguably take most responsibility for launching his career in the late 1950s and 1960s, whom Eastwood described as being "like a second father to me".[39] On Leonard's advice Eastwood switched talent agencies to the Kumin-Olenick Agency in 1956 and to Mitchell Gertz in 1957. He landed several small roles in 1956 as a temperamental army officer for a segment of ABC's Reader's Digest series, and as a motorcycle gang member on a Highway Patrol episode.[38] Eastwood had a minor uncredited role as a ranch hand in his first western film, Law Man, in June 1956.[34] The following year he played a cadet in the West Point television series and a suicidal gold prospector in Death Valley Days.[40] In 1955 he played a Navy lieutenant in a segment of Navy Log and in early 1959 he made a notable guest appearance on Maverick, opposite James Garner, as a cowardly villain intent on marrying a rich girl for money.[40] Eastwood had a small part as an aviator in the French picture Lafayette Escadrille and took on a major role as an ex-Confederate renegade in Ambush at Cimarron Pass, a film which Eastwood viewed as disastrous and the lowest point of his career.[41][42][43]

Rawhide

"Lazy, and would cost you a morning. I never started a day with Clint Eastwood in the first scene, because you knew he was gonna be late, at least a half hour or an hour."

In a long sought-after career breakthrough, Eastwood was cast as Rowdy Yates for the CBS hour-long western series Rawhide in 1958,[45][46] although he was not especially happy with his role. By now, aged almost 30, he felt that his character Rowdy was too young and too cloddish for him to feel comfortable with the part.[47] Filming began in Arizona in the summer of 1958[48] and on release it took just three weeks for Rawhide to reach the top 20 in the TV ratings. Although the series never won an Emmy it was a major success for several years, reaching its peak at number six in the ratings between October 1960 and April 1961.[49] The Rawhide years (1959–65) were some of the most grueling of Eastwood's career. He often filmed for six days a week at an average of twelve hours a day, yet some directors still criticized him for not working hard enough.[44][49] By late 1963 Rawhide's popularity had declined. Lacking freshness in the scripts, it was canceled in the middle of the 1965–66 television season.[50] Eastwood made his first attempt at directing when he filmed several trailers for the show, although he was unable to convince producers to let him direct an episode.[51] In the show's first season Eastwood earned $750 (US$5,697 in 2011 dollars[25]) an episode. At the time of its cancellation he received a $119,000 (US$828,341 in 2011 dollars[25]) compensation package.[52]

1960s

In late 1963 Eastwood's co-star on Rawhide, Eric Fleming, rejected an offer to star in an Italian-made western called A Fistful of Dollars, to be directed in a remote region of Spain by Sergio Leone, who was relatively unknown at the time.[53] Other actors, including Charles Bronson, Steve Reeves, Richard Harrison, Frank Wolfe, Henry Fonda, James Coburn, and Ty Hardin, were also considered for the role. Knowing that he could play a cowboy convincingly Harrison suggested Eastwood, who in turn saw the film as an opportunity to escape from Rawhide. He signed a contract for $15,000 (US$106,211 in 2011 dollars[25]) in wages for eleven weeks' work with a bonus of a Mercedes automobile upon completion and arrived in Rome in May 1964[54][55] Eastwood later spoke about the transition from a television western to A Fistful of Dollars: "In Rawhide I did get awfully tired of playing the conventional white hat. The hero who kisses old ladies and dogs and was kind to everybody. I decided it was time to be an anti-hero."[56] Eastwood was instrumental in creating the Man with No Name character's distinctive visual style and, although a non-smoker, Leone insisted he smoke cigars as an essential ingredient of the "mask" he was attempting to create with the loner character.[57]

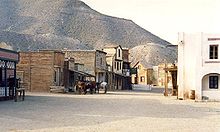

Some interior shots for A Fistful of Dollars were done at the Cinecittà studio on the outskirts of Rome, before production moved to a small village in Andalusia, Spain.[58] The film became a benchmark in the development of spaghetti westerns, with Leone depicting a more lawless and desolate world than in traditional westerns; meanwhile challenging stereotypical American notions of a western hero by replacing him with a morally ambiguous antihero. The film's success meant Eastwood became a major star in Italy[59] and he was re-hired by Leone to star in For a Few Dollars More (1965), the second film of the trilogy. Through the efforts of screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni, the rights to the film and the final film of the trilogy (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) were sold to United Artists for roughly $900,000 (US$6.26 million in 2011 dollars[25]).[60]

"I wanted to play it with an economy of words and create this whole feeling through attitude and movement. It was just the kind of character I had envisioned for a long time, keep to the mystery and allude to what happened in the past. It came about after the frustration of doing Rawhide for so long. I felt the less he said the stronger he became and the more he grew in the imagination of the audience."

In January 1966 Eastwood met with producer Dino De Laurentiis in New York City and agreed to star in a non-western five-part anthology production named Le streghe ("The Witches") opposite De Laurentiis' wife, actress Silvana Mangano.[62] Eastwood's nineteen-minute installment only took a few days to shoot but his performance did not go down well with the critics, with one saying "no other performance of his is quite so 'un-Clintlike' ".[63] Two months later Eastwood began work on the third Dollars film, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, in which he again played the mysterious Man with No Name. Lee Van Cleef returned to play a ruthless fortune seeker, while Eli Wallach portrayed the cunning Mexican bandit Tuco. The storyline involves the search for a cache of Confederate gold buried in a cemetery. One day during filming of a scene where a bridge was to be dynamited Eastwood, suspicious of explosives, urged Wallach to retreat to the hilltop saying, "I know about these things. Stay as far away from special effects and explosives as you can."[64] Minutes later crew confusion, over the word "Vaya!", resulted in a premature explosion which could have killed the co-star, while necessitating rebuilding of the bridge.[64]

The Dollars trilogy was not shown in the United States until 1967 when A Fistful of Dollars opened in January, For a Few Dollars More in May, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly in December.[65] All the films proved successful in cinemas, particularly The Good, the Bad and the Ugly which eventually earned $8 million (US$52.6 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in rental earnings and turned Eastwood into a major film star.[65] All three films received generally bad reviews and marked the beginning of Eastwood's battle to win the respect of American film critics.[66] Judith Crist described A Fistful of Dollars as "cheapjack",[67] while Newsweek considered For a Few Dollars More as "excruciatingly dopey".[66] Renata Adler of The New York Times remarked that The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was "the most expensive, pious and repellent movie in the history of its peculiar genre",[68] despite the fact that it is now widely considered one of the finest films in the history of cinema.[69][70] Time magazine highlighted the film's wooden acting, especially Eastwood's, although critics such as Vincent Canby and Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised Eastwood's coolness in playing the tall, lone stranger.[71] Leone's unique style of cinematography was widely acclaimed, even by some critics who panned the acting.[66]

Stardom brought more "tough guy" roles for Eastwood. He signed for the American revisionist western Hang 'Em High (1968), in which he featured alongside Inger Stevens, Pat Hingle, Dennis Hopper, Ed Begley, Bruce Dern, and James MacArthur.[72] A cross between Rawhide and Leone's westerns, the film brought him a salary of $400,000 (US$2.53 million in 2011 dollars[25]) and 25% of its net earnings.[72] He plays a man who seeks revenge after being lynched by vigilantes and left for dead.[73] Using money earned from the Dollars trilogy Leonard helped establish Eastwood's production company, Malpaso Productions, named after the Malpaso Creek on Eastwood's property in Monterey County, California. Leonard arranged for Hang 'Em High to be a joint production with United Artists[74] and, when it opened in July 1968, the film became the biggest United Artists opening in history — its box office receipts exceeding all the James Bond films of the time.[75][76] It was widely praised by critics; including Archer Winsten of the New York Post who described Hang 'Em High as, "a western of quality, courage, danger and excitement".[10]

Before the release of Hang 'Em High Eastwood had already begun work on the film Coogan's Bluff, about an Arizona deputy sheriff tracking a wanted psychopathic criminal (Don Stroud) through the streets of New York City. He was reunited with Universal Studios for the project after receiving an offer of $1 million (US$6.58 million in 2011 dollars[25])—more than double his previous salary.[76] Jennings Lang arranged for Eastwood to meet Don Siegel, a Universal contract director who later became one of Eastwood's close friends, with the two forming a close partnership that would last for more than ten years over five films.[77] Filming began in November 1967, before the full script had been finalized.[78] The film was controversial for its portrayal of violence,[79][80] with Eastwood's role creating the prototype for what would later become the macho cop of the Dirty Harry films. Coogan's Bluff also became the first collaboration with Argentine composer Lalo Schifrin, who would later compose the jazzy score to several of Eastwood's films in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly the Dirty Harry film series.

Eastwood was paid $850,000 (US$5.37 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in 1968 for the war epic Where Eagles Dare,[81] about a World War II squad parachuting into a Gestapo stronghold in the mountains. Richard Burton played the squad's commander with Eastwood as his right-hand man. He was also cast as Two-Face in the Batman television show, but the series was canceled before filming could commence.[82]

Eastwood then branched out to star in the only musical of his career, Paint Your Wagon (1969). Eastwood and fellow non-singer Lee Marvin play gold miners who share the same wife (portrayed by Jean Seberg). Bad weather and delays plagued the production while its budget eventually exceeded $20 million (US$120 million in 2011 dollars[25]), extremely expensive for the time.[83] The film was not a critical or commercial success, although it was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[84]

1970s

In 1970, Eastwood starred in the western Two Mules for Sister Sara with Shirley MacLaine and directed by Don Siegel. The film follows an American mercenary who gets mixed up with a whore disguised as a nun and ends up helping a group of Juarista rebels during the reign of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico.[85][86] Eastwood once again played a mysterious stranger—unshaven, wearing a serape-like vest, and smoking a cigar.[87] Although the film received moderate reviews[88][89][90]the film is listed in The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made.[91] Later the same year Eastwood starred as one of a group of Americans who steal a fortune in gold from the Nazis in the World War II film Kelly's Heroes with Donald Sutherland and Telly Savalas. Kelly's Heroes was the last film in which Eastwood appeared that was not produced by his own Malpaso Productions.[92] Filming commenced in July 1969 on location in Yugoslavia and in London.[93] The film received mostly a positive reception and its anti-war sentiments were recognized.[92] In the winter of 1969–70, Eastwood and Siegel began planning his next film, The Beguiled, a tale of a wounded Union soldier held captive by the sexually repressed matron of a southern girl's school.[94] Upon release the film received major recognition in France and is considered one of Eastwood's finest works by the French.[95] However, it grossed less than $1 million (US$5.66 million in 2011 dollars[25]) and, according to Eastwood and Lang, flopped due to poor publicity and the "emasculated" role of Eastwood.[96]

"Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino play losers very well. But my audience like to be in there vicariously with a winner. That isn't always popular with critics. My characters have sensitivity and vulnerabilities, but they're still winners. I don't pretend to understand losers. When I read a script about a loser I think of people in life who are losers and they seem to want it that way. It's a compulsive philosophy with them. Winners tell themselves, I'm as bright as the next person. I can do it. Nothing can stop me."

Eastwood's career reached a turning point in 1971.[97] Before Irving Leonard died he and Eastwood had discussed the idea of Malpaso producing Play Misty for Me, a film that was to give Eastwood the artistic control he desired and his debut as a director.[98] The script was about a jazz disc jockey named Dave (Eastwood) who has a casual affair with Evelyn (Jessica Walter), a listener who had been calling the radio station repeatedly at night asking him to play her favorite song—Erroll Garner's "Misty". When Dave ends their relationship the fan becomes violent and murderous.[99] Filming commenced in Monterey in September 1970 and included footage of that year's Monterey Jazz Festival.[100] The film was highly acclaimed with critics such as Jay Cocks in Time, Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice, and Archer Winsten in the New York Post all praising the film, as well as Eastwood's directorial skills and performance.[101] Walter was nominated for a Golden Globe Best Actress Award (Drama) for her performance in the film.

"I know what you're thinking — 'Did he fire six shots or only five?' Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I've kinda lost track myself. But, being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?"

The script for Dirty Harry (1971) was written by Harry Julian Fink and Rita M. Fink. It is a story about a hard-edged New York City (later changed to San Francisco) police inspector named Harry Callahan who is determined to stop a psychotic killer by any means.[102] Dirty Harry is arguably Eastwood's most memorable character and has been credited with inventing the "loose-cannon cop genre", which is still imitated to this day.[103][104] Author Eric Lichtenfeld argues that Eastwood's role as Dirty Harry established the "first true archetype" of the action film genre.[105] His lines (quoted at left) have been cited as among the most memorable in cinematic history and are regarded by firearms historians, such as Garry James and Richard Venola, as the force which catapulted the ownership of .44 Magnum pistols to unprecedented heights in the United States; specifically the Smith & Wesson Model 29 carried by Harry Callahan.[106][107] Dirty Harry proved a phenomenal success after its release in December 1971, earning some $22 million (US$119 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in the United States and Canada alone.[108] It was Siegel's highest-grossing film and the start of a series of films featuring the character of Harry Callahan. Although a number of critics praised his performance as Dirty Harry, such as Jay Cocks of Time magazine who described him as "giving his best performance so far, tense, tough, full of implicit identification with his character",[109] the film was widely criticized and accused of fascism.[110][111][112]

Following Sean Connery's announcement that he would not play James Bond again Eastwood was offered the role but turned it down because he believed the character should be played by an English actor.[113] He next starred in the loner Western Joe Kidd (1972), based on a character inspired by Reies Lopez Tijerina who stormed a courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico, in June 1967. Filming began in Old Tucson in November 1971 under director John Sturges. During the filming, Eastwood suffered symptoms of a bronchial infection and several panic attacks.[114] Joe Kidd received a mixed reception, with Roger Greenspun of The New York Times writing that the film was unremarkable, with foolish symbolism and sloppy editing, although he praised Eastwood's performance.[115]

In 1973 Eastwood directed his first western, High Plains Drifter, in which he starred alongside Verna Bloom, Marianna Hill, Billy Curtis, Rawhide's Paul Brinegar and Geoffrey Lewis. The film had a moral and supernatural theme, later emulated in Pale Rider. The plot follows a mysterious stranger (Eastwood) who arrives in a brooding Western town where the people hire him to defend the town against three felons who are soon to be released. There remains confusion during the film as to whether the stranger is the brother of the deputy, whom the felons lynched and murdered, or his ghost. Holes in the plot were filled with black humor and allegory, influenced by Leone.[116] The revisionist film received a mixed reception from critics, but was a major box office success. A number of critics thought Eastwood's directing was "as derivative as it was expressive", with Arthur Knight of the Saturday Review remarking that Eastwood had "absorbed the approaches of Siegel and Leone and fused them with his own paranoid vision of society".[117] John Wayne, who had declined a role in the film, sent a letter of disapproval to Eastwood some weeks after the film's release saying that "the townspeople did not represent the true spirit of the American pioneer, the spirit that made America great".[118]

Eastwood next turned his attention towards Breezy (1973), a film about love blossoming between a middle-aged man and a teenage girl. During casting for the film Eastwood met Sondra Locke for the first time, an actress who would play major roles in many of his films for the next ten years and would become an important figure in his life.[119] Kay Lenz was awarded the part of Breezy because Locke, at 28, was considered too old. The film, shot very quickly and efficiently by Eastwood and Frank Stanley, came in $1 million (US$4.94 million in 2011 dollars[25]) under budget and was finished three days ahead of schedule.[120] Breezy was not a major critical or commercial success; it barely reached the Top 50 before disappearing and was only made available on video in 1998.[121]

Once filming of Breezy had finished, Warner Brothers announced that Eastwood had agreed to reprise his role as Detective Harry Callahan in Magnum Force (1973), a sequel to Dirty Harry, about a group of rogue young officers (among them David Soul, Robert Urich and Tim Matheson) in the San Francisco Police Force who systematically exterminate the city's worst criminals.[122] Although the film was a major success after release, grossing $58.1 million (US$287 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in the United States alone and a new record for Eastwood, it was not a critical success.[123][124] The New York Times critic Nora Sayre panned the often contradictory moral themes of the film, while the paper's Frank Rich called it "the same old stuff".[124]

In 1974 Eastwood teamed up with Jeff Bridges and George Kennedy in the buddy action caper Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, a road movie about a veteran bank robber Thunderbolt (Eastwood) and a young con man drifter, Lightfoot (Bridges). On its release, in spring 1974, the film was praised for its offbeat comedy mixed with high suspense and tragedy but was only a modest success at the box office, earning $32.4 million (US$144 million in 2011 dollars[25]).[125] Eastwood's acting was noted by critics but was overshadowed by Bridges who was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Eastwood reportedly fumed at the lack of Academy Award recognition for him and swore that he would never work for United Artists again.[125][126]

Eastwood's next film The Eiger Sanction (1975) was based on Trevanian's critically acclaimed spy novel of the same name. Eastwood plays Jonathan Hemlock in a role originally intended for Paul Newman, an assassin turned college art professor who decides to return to his former profession for one last sanction in return for a rare Pissarro painting. In the process he must climb the north face of the Eiger in Switzerland under perilous conditions. Once again Eastwood starred alongside George Kennedy. Mike Hoover taught Eastwood how to climb during several weeks of preparation at Yosemite in the summer of 1974 before filming commenced in Grindelwald on August 12, 1974.[127][128] Despite prior warnings about the perils of the Eiger the film crew suffered a number of accidents, including one fatality.[129][130] In spite of the danger Eastwood insisted on doing all his own climbing and stunts. Upon its release in May 1975 The Eiger Sanction was a commercial failure, receiving only $23.8 million (US$97.1 million in 2011 dollars[25]) at the box office, and was panned by most critics.[131] Joy Gould Boyum of the Wall Street Journal dismissed the film as "brutal fantasy".[131][132] Eastwood blamed Universal Studios for the film's poor promotion and turned his back on them to make an agreement with Warner Brothers, through Frank Wells, that has lasted to the present day.[133]

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), a western inspired by Asa Carter's eponymous 1972 novel,[134] has lead character Josey Wales (Eastwood) as a pro-Confederate guerilla who refuses to surrender his arms after the American Civil War and is chased across the old southwest by a group of enforcers. Eastwood cast his young son Kyle Eastwood, Chief Dan George, and Sondra Locke for the first time, against the wishes of director Philip Kaufman.[135] Kaufman was notoriously fired by producer Bob Daley under Eastwood's command, resulting in a fine reported to be around $60,000 (US$231,484 in 2011 dollars[25]) from the Directors Guild of America—who subsequently passed new legislation reserving the right to impose a major fine on a producer for discharging a director and taking his place.[136] The film was pre-screened at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities in Idaho during a six-day conference entitled Western Movies: Myths and Images. Invited to the screening were: some 200 esteemed film critics, including Jay Cocks and Arthur Knight; directors such as King Vidor, William Wyler, and Howard Hawks; along with a number of academics.[137] Upon release in August 1976 The Outlaw Josey Wales was widely acclaimed, with many critics and viewers seeing Eastwood's role as an iconic one that related to America's ancestral past and the destiny of the nation after the American Civil War.[137] Roger Ebert compared the nature and vulnerability of Eastwood's portrayal of Josey Wales with his Man with No Name character in the Dollars westerns and praised the film's atmosphere.[138] The film would later appear in Time's "Top 10 Films of the Year".[139]

Eastwood was then offered the role of Benjamin L. Willard in Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now, but declined as he did not want to spend weeks on location in the Philippines.[140][141] He also refused the part of a platoon leader in Ted Post's Vietnam War film Go Tell the Spartans[140] and instead decided to make a third Dirty Harry film The Enforcer. The film had Harry partnered with a new female officer (Tyne Daly) to face a San Francisco Bay area group resembling the Symbionese Liberation Army. The film, culminating in a shootout on Alcatraz island, was considerably shorter than the previous Dirty Harry films at 95 minutes,[142] but was a major commercial success grossing $100 million (US$386 million in 2011 dollars[25]) worldwide to become Eastwood's highest-grossing film to date.[143]

In 1977 he directed and starred in The Gauntlet opposite Locke, Pat Hingle, William Prince, Bill McKinney, and Mara Corday. He portrays a down-and-out cop who falls in love with a prostitute that he is assigned to escort from Las Vegas to Phoenix, to testify against the mob. Although a moderate hit with the viewing public critics had mixed feelings about the film, with many believing it was overly violent. Eastwood's longtime nemesis Pauline Kael called it "a tale varnished with foul language and garnished with violence". Roger Ebert, on the other hand, gave it three stars and called it "...classic Clint Eastwood: fast, furious, and funny."[144] In 1978 Eastwood starred in Every Which Way but Loose alongside Locke, Geoffrey Lewis, Ruth Gordon and John Quade. In an uncharacteristic offbeat comedy role, Eastwood played Philo Beddoe, a trucker and brawler who roams the American West searching for a lost love accompanied by his brother and an orangutan called Clyde. The film proved a surprising success upon its release and became Eastwood's most commercially successful film at the time. Panned by the critics it ranked high amongst the box office successes of his career and was the second-highest grossing film of 1978.[145]

Eastwood starred in the atmospheric thriller Escape from Alcatraz in 1979, the last of his films to be directed by Don Siegel. It was based on the true story of Frank Lee Morris who, along with John and Clarence Anglin, escaped from the notorious Alcatraz prison in 1962. The film was a major success and marked the beginning of a period of praise for Eastwood from the critics; Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic lauding it as "crystalline cinema"[146] and Frank Rich of Time describing it as "cool, cinematic grace".[147]

1980s

Eastwood directed the 1980 comedy Bronco Billy as well as playing the lead role in alongside Locke, Scatman Crothers, and Sam Bottoms.[148] His children, Kyle and Alison, also had small roles as orphans.[149] Eastwood has cited Bronco Billy as being one of the most affable shoots of his career and biographer Richard Schickel has argued that the character of Bronco Billy is Eastwood's most self-referential work.[150][151] The film was a commercial failure[152] but was appreciated by critics. Janet Maslin of The New York Times believed the film was "the best and funniest Clint Eastwood movie in quite a while", praising Eastwood's directing and the way he intricately juxtaposes the old West and the new.[153] Later in 1980 Eastwood starred in Any Which Way You Can, the sequel to Every Which Way but Loose. The film received a number of bad reviews from critics, although Maslin described it as "funnier and even better than its predecessor".[152] The film became another box office success and was among the top five highest-grossing films of the year.

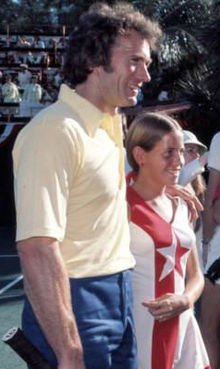

Eastwood in 1981

Eastwood in 1981

In 1982 Eastwood directed and starred alongside his son Kyle in Honkytonk Man, based on the eponymous Clancy Carlile's depression-era novel. Eastwood portrays a struggling western singer Red Stovall who suffers from tuberculosis, but has finally been given an opportunity to make it big at the Grand Ole Opry. He is accompanied by his young nephew (Kyle) to Nashville, Tennessee where he is supposed to record a song. Only Time gave the film a good review in the United States, with most reviewers criticizing its blend of muted humor and tragedy.[154] Nevertheless the film received critical acclaim in France, where it was compared to John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath,[155] and it has since acquired the very high rating of 93% on Rotten Tomatoes.[156] In that same year Eastwood directed, produced, and starred in the Cold War-themed Firefox alongside Freddie Jones, David Huffman, Warren Clarke and Ronald Lacey. Based on a 1977 novel with the same name written by Craig Thomas, the film was shot before Honkeytonk Man but was released after it. Russian filming locations were not possible due to the Cold War, and the film had to be shot in Vienna and other locations in Austria to simulate many of the Eurasian story locations. With a production cost of $20 million (US$45.5 million in 2011 dollars[25]) it was Eastwood's highest budget film to date.[157] People magazine likened Eastwood's performance to "Luke Skywalker trapped in Dirty Harry's Soul".[157]

Sudden Impact, the fourth Dirty Harry film, was shot in the spring and summer of 1983 and is widely considered to be the darkest and most violent of the series.[158] By this time Eastwood received 60% of all profits from films he starred in and directed, with the rest going to the studio.[159] Sudden Impact was the last film which he starred in with Locke. She plays a woman raped, along with her sister, by a ruthless gang at a fairground and seeks revenge for her sister's now vegetative state by systematically murdering her rapists. The line "Go ahead, make my day", uttered by Eastwood during an early scene in a coffee shop, is often cited as one of cinema's immortal ones; famously quoted by President Ronald Reagan in a speech to Congress and used during the 1984 presidential elections.[160][161][162] The film was the highest-earning of all the Dirty Harry films earning $70 million (US$154 million in 2011 dollars[25]). It received rave reviews with many critics praising the feminist aspects of the film, through its explorations of the physical and psychological consequences of rape.[163]

Tightrope (1984) had Eastwood starring opposite his daughter Alison, Geneviève Bujold, and Jamie Rose in a provocative thriller, inspired by newspaper articles about an elusive Bay Area rapist. Set in New Orleans, to avoid confusion with the Dirty Harry films,[164] Eastwood played a single-parent cop drawn into his target's tortured psychology and fascination for sadomasochism.[165] He next starred in the period comedy City Heat (1984) alongside Burt Reynolds, a film about a private eye and his partner who get mixed up with gangsters in the prohibition era of the 1930s. It grossed around $50 million (US$106 million in 2011 dollars[25]) domestically, but was overshadowed by Eddie Murphy's Beverly Hills Cop and failed to meet expectations.[166]

"Westerns. A period gone by, the pioneer, the loner operating by himself, without benefit of society. It usually has something to do with some sort of vengeance; he takes care of the vengeance himself, doesn't call the police. Like Robin Hood. It's the last masculine frontier. Romantic myth. I guess, though it's hard to think about anything romantic today. In a Western you can think, Jesus, there was a time when man was alone, on horseback, out there where man hasn't spoiled the land yet."

Eastwood made his only foray into TV direction with the 1985 Amazing Stories episode "Vanessa In The Garden", which starred Harvey Keitel and Sondra Locke. This was his first collaboration with Steven Spielberg, who later co-produced Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima.[168] Eastwood revisited the western genre when he directed and starred in Pale Rider (1985) opposite Michael Moriarty and Carrie Snodgress. The film is based on the classic 1953 western Shane and follows a preacher descending from the mists of the Sierras to side with the miners during the California Gold Rush of 1850.[169] The title is a reference to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as the rider of the pale horse is Death, and shows similarities to Eastwood's 1973 western High Plains Drifter in its themes of morality and justice as well as its exploration of the supernatural.[170] Pale Rider became one of Eastwood's most successful films to date. It was hailed as one of the best films of 1985 and the best western in years with Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune remarking, "This year (1985) will go down in film history as the moment Clint Eastwood finally earned respect as an artist".[171]

In 1986 Eastwood co-starred with Marsha Mason in the military drama Heartbreak Ridge, about the 1983 United States invasion of Grenada. He portrays an aging United States Marine Gunnery Sergeant and Korean War veteran. The production and filming of Heartbreak Ridge were marred by internal disagreements, between Eastwood and long-time friend and producer Fritz Manes as well as between Eastwood and the United States Department of Defense who expressed contempt for the film.[172][173] At the time the film was a commercial rather than a critical success, only becoming viewed more favorably in recent times.[174] The film was released in 1,470 theaters and grossed $70 million (US$140 million) domestically.[175]

Eastwood starred in The Dead Pool (1988), the fifth and final Dirty Harry film in the series. It co-starred Liam Neeson, Patricia Clarkson, and a young Jim Carrey who plays Johnny Squares, a drug-addled rock star and the first of the victims on a list of celebrities drawn up by horror film director Peter Swan (Neeson) who are deemed most likely to die, the so-called "Dead Pool". The list is stolen by an obsessed fan, who in mimicking his favorite director, systematically makes his way through the list killing off celebrities, of which Dirty Harry is also included. The Dead Pool grossed nearly $38 million (US$70.6 million), relatively low receipts for a Dirty Harry film and it is generally viewed as the weakest film of the series, although Roger Ebert perceived it to be as good as the original.[176][177]

Eastwood began working on smaller, more personal projects, and experienced a lull in his career between 1988 and 1992. Always interested in jazz he directed Bird (1988), a biopic starring Forest Whitaker as jazz musician Charlie "Bird" Parker. Alto saxophonist Jackie McLean and Spike Lee, son of jazz bassist Bill Lee and a long time critic of Eastwood, criticized the characterization of Charlie Parker remarking that it did not capture his true essence and sense of humor.[178] Eastwood received two Golden Globes for the film, the Cecil B. DeMille Award for his lifelong contribution, and the Best Director award. However, Bird was a commercial disaster earning just $11 million, which Eastwood attributed to the declining interest in jazz among black people.[179]

Carrey would again appear with Eastwood in the poorly received comedy Pink Cadillac (1989) alongside Bernadette Peters. The film is about a bounty hunter and a group of white supremacists chasing an innocent woman who tries to outrun everyone in her husband's prized pink Cadillac. The film was a disaster, both critically and commercially,[180] earning barely more than Bird and marking the lowest point in Eastwood's career in years.[181]

1990s

Eastwood directed and starred in White Hunter Black Heart (1990), an adaptation of Peter Viertel's roman à clef, about John Huston and the making of the classic film The African Queen. Shot on location in Zimbabwe in the summer of 1989,[182] the film received some critical attention but with only a limited release earned just $8.4 million (US$14.1 million in 2011 dollars[25]).[183] Later the same year Eastwood directed and co-starred with Charlie Sheen in The Rookie, a buddy cop action film. Critics found the macho jiving between Eastwood and Sheen unconvincing and passed the film off as "blatant racial Hispanic stereotyping".[184] An ongoing lawsuit filed by Stacy McLaughlin resulted in no Eastwood films showing in cinemas in 1991—the third time in his career.[185] The suit was in response to Eastwood allegedly ramming McLaughlin's car while backing out of his parking space at Malpaso.[186] Eastwood won the suit and agreed to pay McLaughlin's court fees if she did not appeal.[185]

"...if possible, he looks even taller, leaner and more mysteriously possessed than he did in Sergio Leone's seminal Fistful of Dollars a quarter of a century ago. The years haven't softened him. They have given him the presence of some fierce force of nature, which may be why the landscapes of the mythic, late 19th-century West become him, never more so than in his new Unforgiven. ... This is his richest, most satisfying performance since the underrated, politically lunatic Heartbreak Ridge. There's no one like him."

In 1992 Eastwood revisited the western genre in the self-directed film Unforgiven, where he played an aging ex-gunfighter long past his prime opposite Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman, Richard Harris, and his then girlfriend Frances Fisher. Scripts existed for the film as early as 1976 under titles such as The Cut-Whore Killings and The William Munny Killings but Eastwood delayed the project, partly because he wanted to wait until he was old enough to play his character and to savor it as the last of his western films.[185] By re-envisioning established genre conventions in a more ambiguous and unromantic light the picture laid the groundwork for later westerns such as Deadwood. Unforgiven was a major commercial and critical success, with nominations for nine Academy Awards[188] including Best Actor for Eastwood and Best Original Screenplay for David Webb Peoples. It won four, including Best Picture and Best Director for Eastwood. Jack Methews of the Los Angeles Times described it as "the finest classical western to come along since perhaps John Ford's 1956 The Searchers.[189] In June 2008 Unforgiven was acknowledged as the fourth best American film in the western genre, behind Shane, High Noon, and The Searchers, in the American Film Institute's "AFI's 10 Top 10" list.[190][191]

Eastwood played Frank Horrigan in the Secret Service thriller In the Line of Fire (1993) directed by Wolfgang Petersen and co-starring John Malkovich and Rene Russo. Horrigan is a guilt-ridden Secret Service agent, haunted by his failure to react in time to save John F. Kennedy's life.[192] As of 2011 it is the last time he acted in a film that he did not direct himself. The film was among the top 10 box office performers in that year, earning a reported $200 million (US$304 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in the United States alone.[193] Later in 1993 Eastwood directed and co-starred with Kevin Costner in A Perfect World. Set in the 1960s,[194]Eastwood plays a Texas Ranger in pursuit of an escaped convict (Costner) who hits the road with a young boy (T.J. Lowther). Janet Maslin of The New York Times remarked that the film was the highest point of Eastwood's directing career[195] and it has since been cited as one of his most underrated directorial achievements.[196][197]

At the May 1994 Cannes Film Festival Eastwood received France's Ordre des Arts et des Lettres medal[198] then on March 27, 1995, he was awarded the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award at the 67th Academy Awards.[199] His next appearance was in a cameo role as himself in the 1995 children's film Casper and continued to expand his repertoire by playing opposite Meryl Streep in the romantic picture The Bridges of Madison County in the same year. Based on a best-selling novel by Robert James Waller and set in Iowa,[200] The Bridges of Madison County relates the story of Robert Kincaid (Eastwood), a photographer working for National Geographic, who has a love affair with middle-aged Italian farm wife Francesca (Streep). The film was a hit at the box office and highly acclaimed by critics, despite unfavorable views of the novel and a subject deemed potentially disastrous for film.[201] Roger Ebert remarked that "Streep and Eastwood weave a spell, and it is based on that particular knowledge of love and self that comes with middle age."[202] The Bridges of Madison County was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Picture and won a César Award in France for Best Foreign Film. Streep was also nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe.

As well as directing the 1997 political thriller Absolute Power, Eastwood once again appeared alongside co-star Gene Hackman. Eastwood played the role of a veteran thief who witnesses the Secret Service cover up of a murder. The film received a mixed reception from critics and was generally viewed as one of his weaker efforts.[203] Maitland McDonagh of TV Guide remarked, "The plot turns are no more ludicrous than those of the average political thriller, but the slow pace makes their preposterousness all the more obvious. Eastwood's acting limitations are also sorely evident, since Luther is the kind of thoughtful thief who has to talk, rather than maintaining the enigmatic fortitude that is Eastwood's forte. Disappointing."[204] Later in 1997 Eastwood directed Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, based on the novel by John Berendt and starring John Cusack, Kevin Spacey, and Jude Law, a film which received a mixed response from critics.[205]

"The roles that Eastwood has played, and the films that he has directed, cannot be disentangled from the nature of the American culture of the last quarter century, its fantasies and its realities."

Eastwood directed and starred in True Crime (1999), which also featured his young daughter Francesca Fisher-Eastwood. He plays Steve Everett, a journalist recovering from alcoholism given the task of covering the execution of murderer Frank Beechum (Isaiah Washington). The film received a mixed reception with Janet Maslin of The New York Times writing, "True Crime is directed by Mr. Eastwood with righteous indignation and increasingly strong momentum. As in A Perfect World, his direction is galvanized by a sense of second chances and tragic misunderstandings, and by contrasting a larger sense of justice with the peculiar minutiae of crime. Perhaps he goes a shade too far in the latter direction, though."[207] If some reviews for True Crime were positive, commercially it was a box office bomb—earning less than half its $55 million (US$72.5 million in 2011 dollars[25]) budget—and easily became Eastwood's worst performing film of the 1990s aside from White Hunter Black Heart, which only had limited release.[208]

2000s

In 2000 Eastwood directed and starred in Space Cowboys alongside Tommy Lee Jones, Donald Sutherland, and James Garner as one of a group of veteran "ex-test pilots" who are sent into space to repair an old Soviet satellite. The original music score was composed by Eastwood and Lennie Niehaus. Space Cowboys was well-received and holds a 79% rating at Rotten Tomatoes.[209] The film received a moderately favorable review from Roger Ebert, "it's too secure within its traditional story structure to make much seem at risk — but with the structure come the traditional pleasures as well."[210] The film grossed over $90 million in its United States release, more than Eastwood's two previous films combined.[211] The following year he played an ex-FBI agent on the track of a sadistic killer (Jeff Daniels) in the thriller Blood Work, loosely based on the 1998 novel of the same name by Michael Connelly. The film was a failure, grossing just $26.2 million (US$32 million in 2011 dollars[25]) on an estimated budget of $50 million (US$61 million in 2011 dollars[25]), and received mixed reviews with a consensus at Rotten Tomatoes calling it "well-made but marred by lethargic pacing".[212] Eastwood did, however, win the Future Film Festival Digital Award at the Venice Film Festival.

"Clint is a true artist in every respect. Despite his years of being at the top of his game and the legendary movies he has made, he always made us feel comfortable and valued on the set, treating us as equals."

Eastwood directed and scored the crime drama Mystic River (2003), a film about murder, vigilantism, and sexual abuse, set in Boston. Starring Sean Penn, Kevin Bacon, and Tim Robbins, Mystic River was lauded by critics and viewers alike. The film won two Academy Awards, Best Actor for Penn and Best Supporting Actor for Robbins, with Eastwood garnering nominations for Best Director and Best Picture.[213] Eastwood was named Best Director of the Year by the London Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics. The film grossed $90 million (US$107 million in 2011 dollars[25]) domestically on a budget of $30 million (US$35.8 million in 2011 dollars[25]).[214]

The following year Eastwood found further critical and commercial success when he directed, produced, scored, and starred in the boxing drama Million Dollar Baby, playing a cantankerous trainer who forms a bond with female boxer (Hilary Swank) who he is persuaded to train by his lifelong friend (Morgan Freeman). The film won four Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress (Swank), and Best Supporting Actor (Freeman).[215] At age 74 Eastwood became the oldest of eighteen directors to have directed two or more Best Picture winners.[216][217] He also received a nomination for Best Actor and a Grammy nomination for his score.[218] A. O. Scott of The New York Times lauded the film as a "masterpiece" and the best film of the year.[219]

In 2006 Eastwood directed two films about World War II's Battle of Iwo Jima. The first, Flags of Our Fathers, focused on the men who raised the American flag on top of Mount Suribachi and was followed by Letters from Iwo Jima, which dealt with the tactics of the Japanese soldiers on the island and the letters they wrote home to family members. Letters from Iwo Jima was the first American film to depict a war issue completely from the view of an American enemy.[220] Both films received praise from critics and garnered several nominations at the 79th Academy Awards, including Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Original Screenplay for Letters from Iwo Jima. At the 64th Golden Globe Awards Eastwood received nominations for Best Director in both films. Letters from Iwo Jima won the award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Eastwood next directed Changeling (2008), based on a true story set in the late 1920s. Angelina Jolie stars as a woman who is reunited with her missing son only to realize that he is an impostor.[221] After its release at several film festivals the film grossed over $110 million (US$112 million in 2011 dollars[25]), the majority of which came from foreign markets.[222] The film was highly acclaimed, with Damon Wise of Empire describing Changeling as "flawless".[223] Todd McCarthy of Variety described it as "emotionally powerful and stylistically sure-handed" and stated that Changeling was a more complex and wide-ranging work than Eastwood's Mystic River, saying the characters and social commentary were brought into the story with an "almost breathtaking deliberation".[224] Film critic Prairie Miller said that, in its portrayal of female courage, the film was "about as feminist as Hollywood can get" whilst David Denby argued that, like Eastwood's Million Dollar Baby, the film was "less an expression of feminist awareness than a case of awed respect for a woman who was strong and enduring."[225] Eastwood received nominations for Best Original Score at the 66th Golden Globe Awards, Best Direction at the 62nd British Academy Film Awards and director of the year from the London Film Critics' Circle.

After four years away from acting Eastwood ended his "self-imposed acting hiatus"[226] with Gran Torino, which he also directed, produced, and partly scored with his son Kyle and Jamie Cullum. Biographer Marc Eliot called Eastwood's role "an amalgam of the Man with No Name, Dirty Harry, and William Munny, here aged and cynical but willing and able to fight on whenever the need arose."[227] Eastwood has said that the role will most likely be the last time he acts in a film.[228] It grossed close to $30 million (US$30.6 million in 2011 dollars[25]) during its wide release opening weekend in January 2009, the highest of his career as an actor or director.[229] Gran Torino eventually grossed over $268 million (US$274 million in 2011 dollars[25]) in theaters worldwide becoming the highest-grossing film of Eastwood's career so far, without adjustment for inflation.

His 30th directorial outing came with Invictus, a film based on the story of the South African team at the 1995 Rugby World Cup, with Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela and Matt Damon as rugby team captain François Pienaar. Freeman had bought the film rights to John Carlin's book on which the film is based.[230] The film met with generally positive reviews; Roger Ebert gave it three and a half stars and described it as a "very good film... with moments evoking great emotion",[231] while Variety's Todd McCarthy wrote, "Inspirational on the face of it, Clint Eastwood's film has a predictable trajectory, but every scene brims with surprising details that accumulate into a rich fabric of history, cultural impressions and emotion."[232] Eastwood was nominated for Best Director at the 67th Golden Globe Awards.

2010s

"Everybody wonders why I continue working at this stage. I keep working because there's always new stories. ... And as long as people want me to tell them, I'll be there doing them."

In 2010, Eastwood directed the drama Hereafter, again working with Damon, who portrayed a psychic. The film had its world premiere on September 12, 2010 at the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival and was given a limited release on October 15, 2010.[234][235] Hereafter received mixed reviews from critics, with the consensus at Rotten Tomatoes being, "Despite a thought-provoking premise and Clint Eastwood's typical flair as director, Hereafter fails to generate much compelling drama, straddling the line between poignant sentimentality and hokey tedium."[236] In the same year, Eastwood served as executive producer for a Turner Classic Movies (TCM) documentary about jazz pianist Dave Brubeck, Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way, to commemorate Brubeck's 90th birthday.[237]

Eastwood directed the 2011 biopic of J. Edgar Hoover, J. Edgar, focusing on the former FBI director's scandalous career and controversial private life. It starred Leonardo DiCaprio as Hoover,[238] Armie Hammer as Clyde Tolson, and Damon Herriman as Bruno Hauptmann. In January 2011, it was announced that Eastwood is in talks to direct Beyoncé Knowles in a fourth remake of the 1937 film A Star Is Born.[239] Production has been delayed due to the pregnancy of Knowles. In October 2011, Entertainment Weekly indicated that Eastwood was in talks to star in a baseball drama where he would play a veteran baseball scout who travels with his daughter for a final scouting trip. Robert Lorenz, who worked with Eastwood as an assistant director on a few of his films, is in talks to direct the film.[240]

Directing style

Beginning with the thriller Play Misty for Me, Eastwood has directed over 30 films in his career; including westerns, action films, and dramas. From the very early days of his career, Eastwood had been frustrated by directors insisting that scenes be re-shot multiple times and perfected, and when he began as a director in 1971, he made a conscious attempt to avoid any aspects of directing he had been indifferent to as an actor. As a result, Eastwood is renowned for his efficient film directing and to reduce filming time and to keep budgets under control. Eastwood usually avoids actors rehearsing and prefers most scenes to be completed on the first take.[241][242] In preparation for filming Eastwood rarely uses storyboards for developing the layout of a shooting schedule.[243][244][245] He also attempts to reduce script background details on characters to allow the audience to become more involved in the film,[246] considering their imagination a requirement for a film that connects with viewers.[246][247] Eastwood has indicated that he lays out a film's plot to provide the audience with necessary details, but not "so much that it insults their intelligence."[248]According to Life magazine, "Eastwood's style is to shoot first and act afterward. He etches his characters virtually without words. He has developed the art of underplaying to the point that anyone around him who so much as flinches looks hammily histrionic."[249]

Interviewers Richard Thompson and Tim Hunter note that Eastwood's films are "superbly paced: unhurried; cool; and [give] a strong sense of real time, regardless of the speed of the narrative"[250] while Ric Gentry considers Eastwood's pacing to be "unrushed and relaxed".[251] Many of Eastwood's films rely on low lighting to give his films a "noir-ish" feel.[242][252] Reviewers have pointed out that the majority of his films are based on the male point-of-view, although female characters typically have strong roles as both heroes and villains.[250][253][254][255]

Politics

Main article: Political life of Clint Eastwood

Left: Eastwood with President Ronald Reagan and Lou Gossett, Jr. in July 1987

Left: Eastwood with President Ronald Reagan and Lou Gossett, Jr. in July 1987

Right: Eastwood as a a spokesman for Take Pride in America in 2005Eastwood registered as a Republican to vote for Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 and later supported Richard Nixon's 1968 and 1972 presidential campaigns. However, he later criticized Nixon's handling of the Vietnam War and his morality during Watergate.[256][257] He expressed his disapproval of America's wars in Korea (1950–1953), Vietnam (1964–1973), and Iraq (2003–2011), believing that the United States should not be overly militaristic or play the role of global policeman. He considers himself too individualistic to be either right-wing or left-wing, describing himself as a "political nothing" and a moderate in 1974[257] and a libertarian in 1997.[258] Eastwood has stated that while he does not see himself as conservative, he is not an "ultra-leftist" either.[259] At times he has supported Democrats in California, including Representative Sam Farr in 2002 and Governor Gray Davis in 2003.[260] A longtime libertarian on social issues, Eastwood has stated that he is pro-choice on abortion.[261] He has endorsed the notion of allowing gays to marry[259] and contributed to groups supporting the Equal Rights Amendment for women.[262]

As a politician Eastwood has made successful forays into both local and state government. In April 1986 he was elected mayor for one term in his home town of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California – a small, wealthy town and artist community on the Monterey Peninsula.[263] During his term he tended towards supporting small business interests and advocating environmental protection.[264] In 2001 Eastwood was appointed to the California State Park and Recreation Commission by Governor Davis,[265] then reappointed in 2004 by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[265] As the vice chairman of the commission, in 2005 along with chairman Bobby Shriver, he led the movement opposed to a six-lane 16-mile (26 km) extension of California State Route 241, a toll road that would cut through San Onofre State Beach. Eastwood and Shriver supported a 2006 lawsuit to block the toll road and urged the California Coastal Commission to reject the project, which it duly did in February 2008.[266] In March 2008 Eastwood and Shriver's non-reappointment to the commission on the expiry of their terms[266] prompted the Natural Resources Defense Council (NDRC) to request a legislative investigation into the decision.[267] Governor Schwarzenegger appointed Eastwood to the California Film Commission in April 2004.[268] He has also acted as a spokesman for Take Pride in America, an agency of the United States Department of the Interior which advocates taking responsibility for natural, cultural, and historic resources.[69]

During the 2008 United States Presidential Election Eastwood endorsed John McCain, whom he has known since 1973, but nevertheless wished Barack Obama well upon his subsequent victory.[269][270] In August 2010 Eastwood wrote to the British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne to protest the decision to close the UK Film Council, warning that the closure could result in fewer foreign production companies choosing to work in the UK.[271]

Personal life

Main article: Personal life of Clint EastwoodRelationships

Eastwood has fathered at least seven children by five different women and has been described as a "serial womanizer".[4][5] According to biographers Eastwood has always had a strong sexual appetite and particularly so during the 1970s. He has had affairs with many women including actresses Catherine Deneuve, Peggy Lipton, Jean Seberg, Kay Lenz, Jamie Rose, Inger Stevens, Jo Ann Harris, Jill Banner, casting director Jane Brolin, script analyst Megan Rose, and swimming champion Anita Lhoest.[272]

Eastwood married Maggie Johnson on December 19, 1953, six months after they met on a blind date.[273] While separated from Johnson, Eastwood had an affair with dancer Roxanne Tunis, with whom he had his first child, Kimber (born June 17, 1964); he did not publicly acknowledge her until 1996.[274] After a reconciliation, he had two children with Johnson: Kyle Eastwood (born May 19, 1968) and Alison Eastwood (born May 22, 1972). Eastwood filed for divorce in 1979 after a long separation, but the $25 million (US$52.9 million in 2011 dollars[25]) divorce settlement was not finalized until May 1984.[275][276]

Eastwood entered a relationship with actress Sondra Locke in 1975, and they lived together for fourteen years despite the fact that she remained married (in name only) to her gay husband, Gordon Anderson.[277][278] They co-starred in six films together: The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet, Every Which Way but Loose, Bronco Billy, Any Which Way You Can, and Sudden Impact. Early on in the relationship, Locke had two abortions and a subsequent tubal ligation.[279][280] The couple separated acrimoniously in 1989; Locke filed a palimony suit against Eastwood after he changed the locks on the home they shared. She sued him a second time, for fraud, regarding an alleged phony directing contract he gave her in settlement of the first lawsuit.[281] Locke and Eastwood went on to resolve the dispute with a non-public settlement in 1999.[282] Her memoir The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly includes a harrowing account of their years together.[283]

During his cohabitation with Locke, Eastwood had an affair with flight attendant Jacelyn Reeves. According to biographers they met at the premiere of Pale Rider where they conceived a son, Scott Reeves (born March 21, 1986).[284] They also had a daughter, Kathryn Reeves (born February 2, 1988), although neither of them were publicly acknowledged until years later.[285] Kathryn served as Miss Golden Globe at the 2005 ceremony where she presented Eastwood with an award for Million Dollar Baby.[286]

In 1990 Eastwood began living with actress Frances Fisher, whom he had met on the set of Pink Cadillac (1989).[287] They co-starred in Unforgiven and had a daughter, Francesca Fisher-Eastwood (born August 7, 1993).[288] The couple ended their relationship in early 1995,[289] but remain friends and later appeared together in True Crime.

Eastwood subsequently began dating Dina Ruiz, an anchorwoman 35 years his junior, whom he had first met when she interviewed him in 1993.[288] They married on March 31, 1996, when Eastwood surprised her with a private ceremony at his home on the Shadow Creek Golf Course in Las Vegas.[290] After their wedding, Dina commented "The fact that I am only the second woman he has married really touches me."[291] The couple has one daughter, Morgan Eastwood (born December 12, 1996).

Eastwood has two grandchildren: Clinton (born 1984) and Graylen (born 1994), by Kimber and Kyle respectively.[292]

Leisure

Despite appearing to smoke in many of his films, Eastwood is a life-long non-smoker, has been conscious of his health and fitness since he was a teenager, and practices healthy eating and daily Transcendental Meditation.[293][294][295] On July 21, 1970, Eastwood's father died unexpectedly of a heart attack at the age of 64. This profoundly altered Eastwood's lifestyle, encouraging him to adopt a vigorous health and exercise regime to ensure his longevity.[99] He abstained from hard liquor, although he still favored cold beer, and opened an old English-inspired pub called the Hog's Breath Inn in Carmel-by-the-Sea in 1971.[296] Eastwood eventually sold the pub and now owns the Mission Ranch Hotel and Restaurant, also located in Carmel-by-the-Sea.[297][298]

Eastwood is a keen golfer and owns the Tehàma Golf Club. He is also an investor in the world-renowned Pebble Beach Golf Links and donates his time every year to charitable causes at major tournaments.[297][299][300] Eastwood was formerly a licensed pilot and often flew his helicopter to the studios to avoid traffic.[301][302]

Music

Main article: Discography of Clint EastwoodEastwood has had a passion for music all his life. He particularly favors jazz and country and western music and is a pianist and composer.[303] Jazz has played an important role in Eastwood's life from a young age and, although he never made it as a professional musician, he passed on the influence to his son Kyle Eastwood, a successful jazz bassist and composer. Eastwood developed as a ragtime pianist early on and had originally intended to pursue a career in music by studying for a music theory degree after graduating from high school. In late 1959 he produced the album Cowboy Favorites, released on the Cameo label.[303]

Eastwood has his own Warner Bros. Records-distributed imprint Malpaso Records, as part of his deal with Warner Brothers, which has released all of the scores of Eastwood's films from The Bridges of Madison County onward. Eastwood co-wrote "Why Should I Care" with Linda Thompson and Carole Bayer Sager, which was recorded by Diana Krall.[304] Eastwood composed the film scores of Mystic River, Grace Is Gone (2007), Changeling, and J. Edgar, and the original piano compositions for In the Line of Fire. He also wrote and performed the song heard over the credits of Gran Torino.[297] The music in Grace Is Gone received two Golden Globe nominations by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association for the 65th Golden Globe Awards. Eastwood was nominated for Best Original Score, while the song "Grace is Gone" with music by Eastwood and lyrics by Carole Bayer Sager was nominated for Best Original Song.[305] It won the Satellite Award for Best Song at the 12th Satellite Awards. Changeling was nominated for Best Score at the 14th Critics' Choice Awards, Best Original Score at the 66th Golden Globe Awards, and Best Music at the 35th Saturn Awards. On September 22, 2007, Eastwood was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the Berklee College of Music at the Monterey Jazz Festival, on which he serves as an active board member. Upon receiving the award he gave a speech claiming, "It's one of the great honors I'll cherish in this lifetime."[306]

Awards and honors

Main articles: List of awards and nominations received by Clint Eastwood and List of awards and nominations received by Clint Eastwood by filmAcademy Awards Year Award Film W/N 1992 Best Director Unforgiven Won Best Picture Unforgiven Won Best Actor Unforgiven Nominated 1994 Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award Won 2003 Best Director Mystic River Nominated Best Picture Mystic River Nominated 2004 Best Director Million Dollar Baby Won Best Picture Million Dollar Baby Won Best Actor Million Dollar Baby Nominated 2006 Best Director Letters from Iwo Jima Nominated Best Picture Letters from Iwo Jima Nominated Eastwood has been recognized with multiple awards and nominations for his work in film, television, and music. His widest reception has been in film work, for which he has received Academy Awards, Directors Guild of America Awards, Golden Globe Awards, and People's Choice Awards, among others. Eastwood is one of only two people to have been twice nominated for Best Actor and Best Director for the same film (Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby) the other being Warren Beatty (Heaven Can Wait and Reds). Along with Beatty, Robert Redford, Richard Attenborough, Kevin Costner, and Mel Gibson, he is one of the few directors best known as an actor to win an Academy Award for directing. On February 27, 2005, he became one of only three living directors (along with Miloš Forman and Francis Ford Coppola) to have directed two Best Picture winners.[307] At age 74, he was also the oldest recipient of the Academy Award for Best Director. Eastwood has directed five actors in Academy Award–winning performances: Gene Hackman in Unforgiven, Tim Robbins and Sean Penn in Mystic River, and Morgan Freeman and Hilary Swank in Million Dollar Baby.

On August 22, 1984, Eastwood was honored at a ceremony at Grauman's Chinese theater to record his hand and footprints in cement.[308] Eastwood received the AFI Life Achievement Award in 1996 and received an honorary degree from AFI in 2009. On December 6, 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Eastwood into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.[309] In early 2007, Eastwood was presented with the highest civilian distinction in France, Légion d'honneur, at a ceremony in Paris. French President Jacques Chirac told Eastwood that he embodied "the best of Hollywood".[310] In October 2009, he was honored by the Lumière Award (in honor of the Lumière Brothers, inventors of the Cinematograph) during the first edition of the Lumière Film Festival in Lyon, France. This award honors his entire career and his major contribution to the 7th Art. In February 2010, Eastwood was recognized by President Barack Obama with an arts and humanities award. Obama described Eastwood's films as "essays in individuality, hard truths and the essence of what it means to be American."[311]

Eastwood has also been awarded at least three honorary degrees from universities and colleges, including an honorary degree from the University of the Pacific in 2006, an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Southern California on May 27, 2007, and an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the Berklee College of Music at the Monterey Jazz Festival on September 22, 2007.[312][313]

Filmography

Eastwood has contributed to over 50 films over his career as actor, director, producer, and composer. He has acted in several television series, most notably starring in Rawhide. He started directing in 1971 and made his debut as a producer in 1982 with Firefox, though he had been functioning as uncredited producer on all of his Malpaso Company films since Hang 'Em High in 1968. Eastwood also has contributed music to his films, either through performing, writing, or composing. He has mainly starred in western, action, and drama films. According to the box office-revenue tracking website, Box Office Mojo, films featuring Eastwood have grossed a total of more than US$1.68 billion domestically, with an average of $37 million per film.[314]

Notes

- ^ Fischer, Landy & Smith, p. 43

- ^ Kitses, p. 307

- ^ a b Eliot, p. 13

- ^ a b Amara, Pavan; Sundberg, Charlotte (May 30, 2010). "Eastwood at 80". The Independent (London). Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vnYapQvw.

- ^ a b c Day, Elizabeth (November 2, 2008). "Gentle Man Clint". The Guardian (London). Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vnYkOYuP.

- ^ McGilligan, p. 22

- ^ http://articles.sfgate.com/2004-02-22/news/17413417_1_stone-youngberg-pebble-beach-death

- ^ Smith, p. 116

- ^ Schickel, p. 27

- ^ a b Zmijewsky, p. 12

- ^ Eliot, p. 15

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (February 6, 2005). "Two Sides Of Clint Eastwood: Lesley Stahl Talks To Oscar-Nominated Actor And Director". CBS Evening News. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vnYqoTvt.

- ^ Kapsis and Coblentz, p. 123 (interviewer Tim Cahill)

- ^ Eliot, p. 17

- ^ Eliot, pp. 18–19

- ^ Eliot, p. 23

- ^ Frank (1982), p. 12

- ^ Schickel, p. 53

- ^ Eliot, p. 25

- ^ Eliot, p. 26

- ^ a b McGilligan, pp. 55–56

- ^ a b c McGilligan, p. 52

- ^ Baldwin, p. 61

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 60

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ McGilligan, p. 62

- ^ University of Southern California. Division of Cinema; American Film Institute; Center for Understanding Media (1972). Filmfacts. Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California. p. 423. http://books.google.com/books?id=NuIvAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Press, p. 100

- ^ Stillman, pp. 130–132

- ^ McGilligan, p. 63

- ^ McGilligan, p. 64

- ^ Fitzgerald & Magers, p. 264

- ^ McGilligan, p. 80

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 81

- ^ McGilligan, p. 86

- ^ Eliot, p. 36

- ^ Hughes, p. xxi

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 85

- ^ Schickel, p. 185

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 87

- ^ Frayling, p. 45

- ^ O'Brien, p. 40

- ^ McGilligan, p. 93

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 111

- ^ McGilligan, p. 95

- ^ Eliot, p. 45

- ^ Miller, Kenneth. "RD Face to Face: Clint Eastwood". Reader's Digest Australia. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080726195125/http://www.readersdigest.com.au/content/rd-face-to-face-clint-eastwood/.

- ^ O'Brien, p. 29

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 110

- ^ McGilligan, p. 125

- ^ Emery, p. 81

- ^ Hughes, p. xxvi

- ^ McGilligan, p. 126

- ^ Eliot, p. 59

- ^ McGilligan, p. 128

- ^ Hughes, p. 4

- ^ McGilligan, p. 131

- ^ McGilligan, p. 134

- ^ Mercer, p. 272

- ^ McGilligan, p. 148

- ^ McGilligan, p. 133

- ^ McGilligan, p. 150

- ^ McGilligan, p. 151

- ^ a b McGillagan, p. 156

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 157

- ^ a b c McGilligan, p. 158

- ^ Crist, Judith (February 2, 1967). "Plain Murder All the Way". New York World Journal Tribune.

- ^ Adler, Renata (January 25, 1968). "The Screen:Zane Grey Meets the Marquis de Sade" (Fee required). The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50F16FE3D5C147493C7AB178AD85F4C8685F9. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Active Interest Media, Inc. (2005-09–2005–10). American Cowboy. Active Interest Media, Inc.. p. 10. ISSN 10793690. http://books.google.com/books?id=c-oCAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA10. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Johnston, p. 277

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (February 2, 1967). "A Fistful of Dollars (1964)" (Fee required). The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40910FC3F5D107B93C0A91789D85F438685F9&scp=1&sq=A+Fistful+of+Dollars&st=p. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 159

- ^ McGilligan, p. 160

- ^ McGilligan, p. 162

- ^ Clint Eastwood's Stock Hits New High, United Artists press release, 1968

- ^ a b McGilligan, p. 165

- ^ McGilligan, p. 167

- ^ McGilligan, p. 169

- ^ Lloyd and Robinson, p. 417

- ^ Slocum, p. 205

- ^ McGilligan, p. 172

- ^ Eliot, p. 83

- ^ McGilligan, p. 173

- ^ "Paint Your Wagon (1969)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vcZqgkCy.

- ^ Frayling, p. 7

- ^ Smith, p. 76

- ^ Schickel, p. 226

- ^ McGilligan, p. 182