- Charlie Chaplin

-

Charlie Chaplin

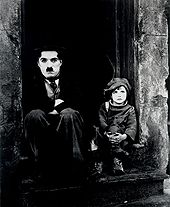

Chaplin as The TrampBirth name Charles Spencer Chaplin Born 16 April 1889

Walworth, London,

United KingdomDied 25 December 1977 (aged 88)

Vevey, Vaud,

SwitzerlandMedium Film, music, mimicry Nationality British Years active 1895–1976[1] Genres Slapstick, mime, visual comedy Influenced Marcel Marceau

The Three Stooges

Federico Fellini

Milton Berle

Peter Sellers

Rowan Atkinson

Johnny Depp

Jacques TatiSpouse Mildred Harris (m. 1918–1921)

1 child

Lita Grey (m. 1924–1927)

2 children

Paulette Goddard (m. 1936–1942)

Oona O'Neill (m. 1943–1977)

8 childrenSignature

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE (16 April 1889 – 25 December 1977) was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work during the silent film era.[2] He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I. Chaplin used mime, slapstick and other visual comedy routines, and continued well into the era of the talkies, though his films decreased in frequency from the end of the 1920s. His most famous role was that of The Tramp, which he first played in the Keystone comedy Kid Auto Races at Venice in 1914.[3] From the April 1914 one-reeler Twenty Minutes of Love onwards he was writing and directing most of his films, by 1916 he was also producing them, and from 1918 he was even composing the music for them. With Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith, he co-founded United Artists in 1919.[4]

Chaplin was one of the most creative and influential personalities of the silent-film era. He was influenced by his predecessor, the French silent film comedian Max Linder, to whom he dedicated one of his films.[5] His working life in entertainment spanned over 75 years, from the Victorian stage and the music hall in the United Kingdom as a child performer, until close to his death at the age of 88. His high-profile public and private life encompassed both adulation and controversy. Chaplin's identification with the left ultimately forced him to resettle in Europe during the McCarthy era in the early 1950s.

In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Chaplin the 10th greatest male screen legend of all time.[6] In 2008, Martin Sieff, in a review of the book Chaplin: A Life, wrote: "Chaplin was not just 'big', he was gigantic. In 1915, he burst onto a war-torn world bringing it the gift of comedy, laughter and relief while it was tearing itself apart through World War I. Over the next 25 years, through the Great Depression and the rise of Adolf Hitler, he stayed on the job. ... It is doubtful any individual has ever given more entertainment, pleasure and relief to so many human beings when they needed it the most".[7] George Bernard Shaw called Chaplin "the only genius to come out of the movie industry".[8]

Contents

Biography

Early life in London (1889–1909)

Charles Spencer Chaplin was born on 16 April 1889, supposedly in East Street, Walworth, London, England.[9] (In 2011, a letter, written to him in the 1970s, came to light, claiming that he had been born in a Gypsy caravan at Black Patch Park in Smethwick, Staffordshire.[10]) His parents were entertainers in the music hall tradition; his father, Charles Spencer Chaplin Sr, was a vocalist and an actor while his mother, Hannah Chaplin, was a singer and an actress who went by the stage name Lilly Harley.[11] They separated before Charlie was three. He learned singing from his parents. The 1891 census shows that his mother lived with Charlie and his older half-brother Sydney on Barlow Street, Walworth.

As a child, Chaplin also lived with his mother in various addresses in and around Kennington Road in Lambeth, including 3 Pownall Terrace, Chester Street and 39 Methley Street. His paternal grandmother's mother was from the Smith family of Romanichals,[12] a fact of which he was extremely proud,[13] though he described it in his autobiography as "the skeleton in our family cupboard".[14] Charles Chaplin Sr. was an alcoholic and had little contact with his son, though Chaplin and his half-brother briefly lived with him and his mistress, Louise, at 287 Kennington Road.[15][16] The half-brothers lived there while their mentally ill mother lived at Cane Hill Asylum at Coulsdon. Chaplin's father's mistress sent the boy to Archbishop Temple's Boys School. His father died of cirrhosis when Charlie was twelve in 1901.[17] As of the 1901 Census, Chaplin resided at 94 Ferndale Road, Lambeth, as part of a troupe of young male dancers, The Eight Lancashire Lads,[18] managed by William Jackson.[19]

A larynx condition ended the singing career of Hannah Chaplin.[20] After her re-admission to the Cane Hill Asylum, her son was left in the workhouse at Lambeth in south London, moving several weeks later to the Central London District School for paupers in Hanwell.

In 1903 Chaplin secured the role of Billy the pageboy in Sherlock Holmes, written by William Gillette and starring English actor H. A. Saintsbury. Saintsbury took Chaplin under his wing and taught him to marshal his talents. In 1905 Gillette came to England with Marie Doro to debut his new play, Clarice, but the play did not go well. When Gillette staged his one-act curtain-raiser, The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes as a joke on the British press, Chaplin was brought in from the provinces to play Billy. When Sherlock Holmes was substituted for Clarice, Chaplin remained as Billy until the production ended on 2 December. During the run, Gillette coached Chaplin in his restrained acting style. Acting in Sherlock Holmes entitled Chaplin to an West End actor's pass for the funeral of Britain's most respected Shakespearean actor, Sir Henry Irving, which he attended, sitting next to the actor Lewis Waller.[21] It was during this engagement that the teenage Chaplin fell hopelessly in love with Doro, but his love went unrequited and Doro returned to America with Gillette when the production closed.[22]

They met again in Hollywood eleven years later. She had forgotten his name but, when introduced to her, Chaplin told her of being silently in love with her and how she had broken his young heart. Over dinner, he laid it on thick about his unrequited love. Nothing came of it until two years later, when they were both in New York and she invited him to dinner and a drive. Instead, Chaplin noted, they simply “dined quietly in Marie’s apartment alone.” However, as Kenneth Lynn pointed out, “Chaplin would not have been Chaplin if he had simply dined quietly with Marie.”[23]

First years in the United States (1910–1913)

Chaplin first toured the United States with the Fred Karno troupe from 1910 to 1912. After five months in England, he returned to the U.S. for a second tour, arriving with the Karno Troupe on 2 October 1912. In the Karno Company was Arthur Stanley Jefferson, who later became known as Stan Laurel. Chaplin and Laurel shared a room in a boarding house. Laurel returned to England but Chaplin remained in the United States. In late 1913, Chaplin's act with the Karno Troupe was seen by Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, Minta Durfee, and "Fatty" Arbuckle. Sennett hired him for his studio, the Keystone Film Company as a replacement for Ford Sterling.[24] Chaplin had considerable difficulty adjusting to the demands of film acting and his performance suffered for it. After Chaplin's first film appearance, Making a Living was filmed, Sennett felt he had made a costly mistake.[25] Most historians agree it was Normand who persuaded him to give Chaplin another chance.[26]

Sennett did not warm to Chaplin right away, and Chaplin believed Sennett intended to fire him following a disagreement with Normand.[27] However, Chaplin's pictures were soon a success, and he became one of the biggest stars at Keystone.[27][28]

Chaplin was given over to Normand, who directed and wrote a handful of his earliest films.[27] Chaplin did not enjoy being directed by a woman, and they often disagreed.[27] Eventually, the two worked out their differences and remained friends long after Chaplin left Keystone.

The Tramp (1914–1915)

The Tramp debuted during the silent film era in the Keystone comedy Kid Auto Races at Venice (released on 7 February 1914). However, Chaplin had devised the tramp costume for a film produced a few days earlier but released later (9 February 1914), Mabel's Strange Predicament. Mack Sennett had requested that Chaplin "get into a comedy make-up".[29] As Chaplin recalled in his autobiography:

I had no idea what makeup to put on. I did not like my get-up as the press reporter [in Making a Living]. However on the way to the wardrobe I thought I would dress in baggy pants, big shoes, a cane and a derby hat. I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. I was undecided whether to look old or young, but remembering Sennett had expected me to be a much older man, I added a small moustache, which I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on stage he was fully born.[30]"The Tramp" is a vagrant with the refined manners, clothes, and dignity of a gentleman. Arbuckle contributed his father-in-law's bowler hat ('derby') and his own pants (of generous proportions). Chester Conklin provided the little cutaway tailcoat, and Ford Sterling the size-14 shoes, which were so big, Chaplin had to wear each on the wrong foot to keep them on. He devised the moustache from a bit of crepe hair belonging to Mack Swain. The only thing Chaplin himself owned was the whangee cane.[29]

Chaplin, with his Little Tramp character, quickly became the most popular star in Sennett's company of players. He immediately gained enormous popularity among cinema audiences. "The Tramp", Chaplin's principal character, was known as "Charlot" in the French-speaking world, Italy, Spain, Andorra, Portugal, Greece, Romania and Turkey, "Carlitos" in Brazil and Argentina, and "Der Vagabund" in Germany.

Chaplin continued to play the Tramp through dozens of short films and, later, feature-length productions (in only a handful of other productions did he play characters other than the Tramp). He portrayed a Keystone Kop in A Thief Catcher filmed 5–26 Jan 1914.[31]

The Tramp was closely identified with the silent era, and was considered an international character; when the sound era began in the late 1920s, Chaplin refused to make a talkie featuring the character. The 1931 production City Lights featured no dialogue. Chaplin officially retired the character in the film Modern Times (released 5 February 1936), which appropriately ended with the Tramp walking down an endless highway toward the horizon. The film was only a partial talkie and is often called the last silent film. The Tramp remains silent until near the end of the film when, for the first time, his voice is finally heard, albeit only as part of a French/Italian-derived gibberish song.

Chaplin's early Keystones use the standard Mack Sennett formula of extreme physical comedy and exaggerated gestures. Chaplin's pantomime was subtler, more suitable to romantic and domestic farces than to the usual Keystone chases and mob scenes. The visual gags were pure Keystone, however; the tramp character would aggressively assault his enemies with kicks and bricks. Moviegoers loved this cheerfully earthy new comedian, even though critics warned that his antics bordered on vulgarity. Chaplin was soon entrusted with directing and editing his own films. He made 34 shorts for Sennett during his first year in pictures, as well as the landmark comedy feature Tillie's Punctured Romance.

The Tramp was featured in the first film trailer to be exhibited in a U.S. cinema, a slide promotion developed by Nils Granlund, advertising manager for the Marcus Loew theatre chain, and shown at the Loew's Seventh Avenue Theatre in Harlem in 1914.[32] In 1915, Chaplin signed a much more favourable contract with Essanay Studios, and further developed his cinematic skills, adding new levels of depth and pathos to the Keystone-style slapstick. Most of the Essanay films were more ambitious, running twice as long as the average Keystone comedy. Chaplin also developed his own stock company, including ingénue Edna Purviance and comic villains Leo White and Bud Jamison.

Chaplin's popularity continued to soar in the early years following the start of WW1. He started to become noticed by stars of the legitimate theatre. Minnie Maddern Fiske, one of the legends of the stage endorsed Chaplin's artistry in an article in Harper's Weekly(6 May 1915). At the start of her article Mrs. Fiske spoke, "...To the writer Charles Chaplin appears as a great comic artist, possessing inspirational powers and a technique as unfaltering as Rejane's. If it be treason to Art to say this, then let those exalted persons who allow culture to be defined only upon their own terms make the most of it..."[33] In the following years Chaplin would make many friends from the world of the Broadway stage.

Chaplin was emerging as the supreme exponent of silent films, an emigrant himself from London. Chaplin's Tramp enacted the difficulties and humiliations of the immigrant underdog, the constant struggle at the bottom of the American heap and yet he triumphed over adversity without ever rising to the top, and thereby stayed in touch with his audience. Chaplin's films were also deliciously subversive. The bumbling officials enabled the immigrants to laugh at those they feared.[34]

Pioneering film artist and global celebrity (1916–1918)

A clip from the Charlie Chaplin silent film, The Bond (1918).

In 1916, the Mutual Film Corporation paid Chaplin US$670,000 to produce a dozen two-reel comedies. He was given near complete artistic control, and produced twelve films over an eighteen-month period that rank among the most influential comedy films in all cinema. Of his Mutual comedies, the best known include: Easy Street, One A.M., The Pawnshop, and The Adventurer. Edna Purviance remained the leading lady, and Chaplin added Eric Campbell, Henry Bergman, and Albert Austin to his stock company; Campbell, a Gilbert and Sullivan veteran, provided superb villainy, and second bananas Bergman and Austin would remain with Chaplin for decades. Chaplin regarded the Mutual period as the happiest of his career, although he also had concerns that the films during that time were becoming formulaic owing to the stringent production schedule his contract required. Upon the U.S. entering World War I, Chaplin became a spokesman for Liberty Bonds with his close friend Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.[28]

Most of the Chaplin films in circulation date from his Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual periods. After Chaplin assumed control of his productions in 1918 (and kept exhibitors and audiences waiting for them), entrepreneurs serviced the demand for Chaplin by bringing back his older comedies. The films were recut, retitled, and reissued again and again, first for theatres, then for the home-film market, and in recent years, for home video. Even Essanay was guilty of this practice, fashioning "new" Chaplin comedies from old film clips and out-takes. The twelve Mutual comedies were revamped as sound films in 1933, when producer Amadee J. Van Beuren added new orchestral scores and sound effects.

At the conclusion of the Mutual contract in 1917, Chaplin signed a contract with First National to produce eight two-reel films. First National financed and distributed these pictures (1918–23) but otherwise gave him complete creative control over production. Chaplin now had his own studio, and he could work at a more relaxed pace that allowed him to focus on quality. Although First National expected Chaplin to deliver short comedies like the celebrated Mutuals, Chaplin ambitiously expanded most of his personal projects into longer, feature-length films, including Shoulder Arms (1918), The Pilgrim (1923) and the feature-length classic The Kid (1921).

United Artists (1919–1939)

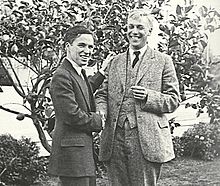

In 1919, Chaplin co-founded the United Artists film distribution company with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith, all of whom were seeking to escape the growing power consolidation of film distributors and financiers in the developing Hollywood studio system. This move, along with complete control of his film production through his studio, assured Chaplin's independence as a film-maker. He served on the board of UA until the early 1950s.

All Chaplin's United Artists pictures were of feature length, beginning with the atypical drama in which Chaplin had only a brief cameo role, A Woman of Paris (1923). This was followed by the classic comedies The Gold Rush (1925) and The Circus (1928).

After the arrival of sound films, Chaplin continued to focus on silent films with a synchronised recorded score, which included sound effects and music with melodies based in popular songs or composed by him;[35] The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), and Modern Times (1936) were essentially silent films. City Lights has been praised for its mixture of comedy and sentimentality. Critic James Agee, for example, wrote in Life magazine in 1949 that the final scene in City Lights was the "greatest single piece of acting ever committed to celluloid".

While Modern Times (1936) is a non-talkie, it does contain talk—usually coming from inanimate objects such as a radio or a TV monitor. This was done to help 1930s audiences, who were out of the habit of watching silent films, adjust to not hearing dialogue. Modern Times was the first film where Chaplin's voice is heard (in the nonsense song at the end, which Chaplin both performed and wrote the nonsense lyrics to). However, for most viewers it is still considered a silent film.

Although "talkies" became the dominant mode of film making soon after they were introduced in 1927, Chaplin resisted making such a film all through the 1930s. He considered cinema essentially a pantomimic art. He said: "Action is more generally understood than words. Like Chinese symbolism, it will mean different things according to its scenic connotation. Listen to a description of some unfamiliar object—an African warthog, for example; then look at a picture of the animal and see how surprised you are".[36]

It is a tribute to Chaplin's versatility that he also has one film credit for choreography for the 1952 film Limelight, and another as a singer for the title music of The Circus (1928). The best known of several songs he composed are "Smile", composed for the film Modern Times (1936) and given lyrics to help promote a 1950s revival of the film, famously covered by Nat King Cole. "This Is My Song" from Chaplin's last film, A Countess from Hong Kong, was a number one hit in several different languages in the late 1960s (most notably the version by Petula Clark and discovery of an unreleased version in the 1990s recorded in 1967 by Judith Durham of The Seekers), and Chaplin's theme from Limelight was a hit in the 1950s under the title "Eternally." Chaplin's score to Limelight won an Academy Award in 1972; a delay in the film premiering in Los Angeles made it eligible decades after it was filmed. Chaplin also wrote scores for his earlier silent films when they were re-released in the sound era, notably The Kid for its 1971 re-release.

The Great Dictator (1940)

Chaplin's first talking picture, The Great Dictator (1940), was an act of defiance against Nazism. It was filmed and released in the United States one year before the U.S. entry into World War II. Chaplin played the role of "Adenoid Hynkel",[37] Dictator of Tomainia, modelled on German dictator Adolf Hitler, who was only four days his junior and sported a similar moustache. The film also showcased comedian Jack Oakie as "Benzino Napaloni", dictator of Bacteria, a jab at Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.[37]

Paulette Goddard filmed with Chaplin again, depicting a woman in the ghetto. The film was seen as an act of courage in the political environment of the time, both for its ridicule of Nazism, for the portrayal of overt Jewish characters, and the depiction of their persecution. In addition to Hynkel, Chaplin also played a look-alike Jewish barber persecuted by the regime. The barber physically resembled the Tramp character.[37]

At the conclusion, the two characters Chaplin portrayed swapped positions through a complex plot, and he dropped out of his comic character to address the audience directly in a speech[38] denouncing dictatorship, greed, hate, and intolerance, in favour of liberty and human brotherhood.

The film was nominated for Academy awards for Best Picture (producer), Best Original Screenplay (writer) and Best Actor.[39]

McCarthy era

Although Chaplin had his major successes in the United States and was a resident from 1914 to 1953, he always maintained a neutral nationalistic stance.[clarification needed] During the era of McCarthyism, Chaplin was accused of "un-American activities" as a suspected communist and J. Edgar Hoover, who had instructed the FBI to keep extensive secret files on him, tried to end his United States residency. FBI pressure on Chaplin grew after his 1942 campaign for a second European front in the war and reached a critical level in the late 1940s, when Congressional figures threatened to call him as a witness in hearings. This was never done, probably from fear of Chaplin's ability to lampoon the investigators.[40]

In 1952, Chaplin left the US for what was intended as a brief trip home to the United Kingdom for the London premiere of Limelight. Hoover learned of the trip and negotiated with the Immigration and Naturalization Service to revoke Chaplin's re-entry permit, exiling Chaplin so he could not return for his alleged political leanings. Chaplin decided not to re-enter the United States, writing: "Since the end of the last world war, I have been the object of lies and propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who, by their influence and by the aid of America's yellow press, have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. Under these conditions I find it virtually impossible to continue my motion-picture work, and I have therefore given up my residence in the United States."[41]

That Chaplin was unprepared to remain abroad, or that the revocation of his right to re-enter the United States by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was a surprise to him, may be apocryphal: An anecdote in some contradiction is recorded during a broad interview with Richard Avedon, celebrated New York portraitist.[42]

Avedon is credited with the last portrait of the entertainer to be taken before his departure to Europe and therefore the last photograph of him as a singularly “American icon.” According to Avedon, Chaplin telephoned him at his studio in New York while on a layover before the final leg of his travel to England. The photographer considered the impromptu self-introduction a prank and angrily answered his caller with the riposte, “If you’re Charlie Chaplin, I’m Franklin Roosevelt!” To mollify Avedon, Chaplin assured the photographer of his authenticity and added the comment, “If you want to take my picture, you'd better do it now. They are coming after me and I won’t be back. I leave ... (imminently).” Avedon interrupted his production commitments to take Chaplin’s portrait the next day, and never saw him again.

Chaplin then made his home in Vevey, Switzerland. He briefly and triumphantly returned to the United States in April 1972, with his wife, to receive an Honorary Oscar, and also to discuss how his films would be re-released and marketed.

Final works (1957–1976)

Chaplin's final two films were made in London: A King in New York (1957) in which he starred, wrote, directed and produced; and A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), which he directed, produced, and wrote. The latter film stars Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando, and Chaplin made his final on-screen appearance in a brief cameo role as a seasick steward. He also composed the music for both films with the theme song from A Countess From Hong Kong, "This is My Song", reaching number one in the UK as sung by Petula Clark. Chaplin also compiled a film The Chaplin Revue from three First National films A Dog's Life (1918), Shoulder Arms (1918) and The Pilgrim (1923) for which he composed the music and recorded an introductory narration. As well as directing these final films, Chaplin also wrote My Autobiography, between 1959 and 1963, which was published in 1964.

In his pictorial autobiography My Life In Pictures, published in 1974, Chaplin indicated that he had written a screenplay for his daughter, Victoria; entitled The Freak, the film would have cast her as an angel. According to Chaplin, a script was completed and pre-production rehearsals had begun on the film (the book includes a photograph of Victoria in costume), but were halted when Victoria married. "I mean to make it some day," Chaplin wrote. However, his health declined steadily in the 1970s which hampered all hopes of the film ever being produced.

From 1969 until 1976, Chaplin wrote original music compositions and scores for his silent pictures and re-released them. He composed the scores of all his First National shorts: The Idle Class in 1971 (paired with The Kid for re-release in 1972), A Day's Pleasure in 1973, Pay Day in 1972, Sunnyside in 1974, and of his feature length films firstly The Circus in 1969 and The Kid in 1971. Chaplin worked with music associate Eric James whilst composing all his scores.

He received a knighthood on 4 March 1975, at the age of 85.[43] Chaplin's last completed work was the score for his 1923 film A Woman of Paris, which was completed in 1976, by which time Chaplin was extremely frail, even finding communication difficult.

Death (1977)

Chaplin's robust health began to slowly fail in the late 1960s, after the completion of his final film A Countess from Hong Kong, and more rapidly after he received his Academy Award in 1972. By 1977, he had difficulty communicating, and was using a wheelchair. Chaplin died in his sleep in Vevey, Switzerland on Christmas Day 1977.[44]

Chaplin was interred in Corsier-Sur-Vevey Cemetery, Switzerland.[45] On 1 March 1978, his corpse was stolen by a small group of Swiss mechanics in an attempt to extort money from his family.[46] The plot failed; the robbers were captured, and the corpse was recovered eleven weeks later near Lake Geneva. His body was reburied under 6 feet (1.8 m) of concrete to prevent further attempts.

Filmmaking techniques

Chaplin never spoke more than cursorily about his filmmaking methods, claiming such a thing would be tantamount to a magician spoiling his own illusion. In fact, until he began making spoken dialogue films with The Great Dictator in 1940, Chaplin never shot from a completed script. The method he developed, once his Essanay contract gave him the freedom to write for and direct himself, was to start from a vague premise—for example "Charlie enters a health spa" or "Charlie works in a pawn shop." Chaplin then had sets constructed and worked with his stock company to improvise gags and "business" around them, almost always working the ideas out on film. As ideas were accepted and discarded, a narrative structure would emerge, frequently requiring Chaplin to reshoot an already-completed scene that might have otherwise contradicted the story.[47] Chaplin's unique filmmaking techniques became known only after his death, when his rare surviving outtakes and cut sequences were carefully examined in the 1983 British documentary Unknown Chaplin.

This is one reason why Chaplin took so much longer to complete his films than his rivals did. In addition, Chaplin was an incredibly exacting director, showing his actors exactly how he wanted them to perform and shooting scores of takes until he had the shot he wanted. Animator Chuck Jones, who lived near Charlie Chaplin's Lone Star studio as a boy, remembered his father saying he watched Chaplin shoot a scene more than a hundred times until he was satisfied with it.[48] This combination of story improvisation and relentless perfectionism—which resulted in days of effort and thousands of feet of film being wasted, all at enormous expense—often proved very taxing for Chaplin, who in frustration would often lash out at his actors and crew, keep them waiting idly for hours or, in extreme cases, shutting down production altogether.[47]

Comparison with other silent comics

Since the 1960s, Chaplin's films have been compared to those of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd (the other two great silent film comedians of the time), especially among the loyal fans of each comic.

The three had different styles: Chaplin had a strong affinity for sentimentality and pathos (which was popular in the 1920s), Lloyd was renowned for his everyman persona and 1920s optimism, and Keaton adhered to onscreen stoicism with a cynical tone more suited to modern audiences.

Commercially, Chaplin made some of the highest-grossing films in the silent era; The Gold Rush is the fifth with US$4.25 million and The Circus is the seventh with US$3.8 million. However, Chaplin's films combined made about US$10.5 million while Harold Lloyd's grossed US$15.7 million. Lloyd was far more prolific, releasing twelve feature films in the 1920s while Chaplin released just three. Buster Keaton's films were not nearly as commercially successful as Chaplin's or Lloyd's even at the height of his popularity, and only received belated critical acclaim in the late 1950s and 1960s.

There is evidence that Chaplin and Keaton, who both got their start in vaudeville, thought highly of one another: Keaton stated in his autobiography that Chaplin was the greatest comedian that ever lived, and the greatest comedy director, whereas Chaplin welcomed Keaton to United Artists in 1925, advised him against his disastrous move to MGM in 1928, and for his last American film, Limelight, wrote a part specifically for Keaton as his first on-screen comedy partner since 1915.

Composer and songwriter

Chaplin wrote or co-wrote the scores and songs for many of his films. "Smile", which he composed for his film, Modern Times, hit number 2 on the UK charts when sung by Nat King Cole in the 1950s.[49] It was also Michael Jackson's favourite song.[50] "This Is My Song", written and composed by Chaplin for his film, A Countess from Hong Kong, hit number 1 on the UK charts when sung by Petula Clark in the 1960s.[51] In 1973, Chaplin won the Oscar for Best Film Score for his film, Limelight.[52] Chaplin was not the only member of his family with musical talent; his nephew, Spencer Dryden was the drummer for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted band, Jefferson Airplane.[53]

Politics

Chaplin's political sympathies always lay with the left. His silent films made prior to the Great Depression typically did not contain overt political themes or messages, apart from the Tramp's plight in poverty and his run-ins with the law, but his 1930s films were more openly political. Modern Times depicts workers and poor people in dismal conditions. The final dramatic speech in The Great Dictator, which was critical of following patriotic nationalism without question, and his vocal public support for the opening of a second European front in 1942 to assist the Soviet Union in World War II were controversial.

Chaplin declined to support the war effort as he had done for World War I which led to public anger, although his two sons saw service in the Army in Europe. For most of World War II he was fighting serious criminal and civil charges related to his involvement with actress Joan Barry (see below). After the war, his 1947 black comedy, Monsieur Verdoux showed a critical view of capitalism. Chaplin's final American film, Limelight, was less political and more autobiographical in nature. His following European-made film, A King in New York (1957), satirised the political persecution and paranoia that had forced him to leave the U.S. five years earlier.

On religion, Chaplin wrote in his autobiography, “In Philadelphia, I inadvertently came upon an edition of Robert Ingersoll's Essays and Lectures. This was an exciting discovery; his atheism confirmed my own belief that the horrific cruelty of the Old Testament was degrading to the human spirit.”

Other controversies

During World War I, Chaplin was criticised in the British press for not joining the Army. He had in fact presented himself for service, but was denied for being too small at 5'5" and underweight. Chaplin raised substantial funds for the war effort during war bond drives not only with public speaking at rallies but also by making, at his own expense, The Bond, a comedic propaganda film used in 1918. The lingering controversy may have prevented Chaplin from receiving a knighthood in the 1930s. A 1916 propaganda short film Zepped with Chaplin was discovered in 2009.[54]

For Chaplin's entire career, some level of controversy existed over claims of Jewish ancestry. Nazi propaganda in the 1930s and 40s prominently portrayed him as Jewish (named Karl Tonstein) relying on articles published in the U.S. press before,[55] and FBI investigations of Chaplin in the late 1940s also focused on Chaplin's ethnic origins. There is no documentary evidence of Jewish ancestry for Chaplin himself. For his entire public life, he fiercely refused to challenge or refute claims that he was Jewish, saying that to do so would always "play directly into the hands of anti-Semites."[56] Although baptised in the Church of England, Chaplin was thought to be an agnostic for most of his life.[57]

Chaplin's lifelong attraction to younger women remains another enduring source of interest to some. His biographers have attributed this to a teenage infatuation with Hetty Kelly, whom he met in Britain while performing in the music hall, and which possibly defined his feminine ideal. Chaplin clearly relished the role of discovering and closely guiding young female stars; with the exception of Mildred Harris, all of his marriages and most of his major relationships began in this manner.

Personal life and family

Chaplin's mother died in 1928 in Glendale, California,[58] seven years after she was brought to the U.S. by her sons. Unknown to Charlie and Sydney until years later, they had a half-brother through their mother. The boy, Wheeler Dryden (1892–1957), was raised abroad by his father but later connected with the rest of the family and went to work for Chaplin at his Hollywood studio.[59] In 1928, Chaplin built the Montecito Inn in Montecito near Santa Barbara as an escape from showbiz with his closest friends.[60]

The South African duo Locnville, Andrew and Brian Chaplin, are related to Chaplin (their grandfather was Chaplin's first cousin).

Relationships

- Hetty Kelly was Chaplin's first love, a dancer with whom he fell in love when she was fifteen and almost married when he was nineteen, in 1908.[61] It is said Chaplin fell madly in love with her and asked her to marry him. When she refused, Chaplin suggested it would be best if they did not see each other again; he was reportedly crushed when she agreed. Years later, her memory would remain an obsession with Chaplin. He was devastated in 1921 when he learned that she had died of influenza during the 1918 flu pandemic.[62]

- Edna Purviance was Chaplin's first major leading lady after Mabel Normand. Purviance and Chaplin were involved in a close romantic relationship during the production of his Essanay and Mutual films in 1916–1917. The romance seems to have ended by 1918, and Chaplin's marriage to Mildred Harris in late 1918 ended any possibility of reconciliation. Purviance would continue as leading lady in Chaplin's films until 1923, and would remain on Chaplin's payroll until her death in 1958. She and Chaplin spoke warmly of one another for the rest of their lives.

- Mildred Harris: On 23 October 1918, Chaplin, age 29, married the popular child actress, Harris, who was 16 at the time. They had one son, Norman Spencer "The Little Mouse" Chaplin, born on 7 July 1919, who died three days later and is interred under the name The Little Mouse at Inglewood Park Cemetery, Inglewood California. Chaplin separated from Harris by late 1919, moving back into the Los Angeles Athletic Club.[63] The couple divorced in November 1920, with Harris getting some of their community property and a US$100,000 settlement.[63] Chaplin admitted that he "was not in love, now that [he] was married [he] wanted to be and wanted the marriage to be a success." During the divorce, Chaplin claimed Harris had an affair with noted actress of the time Alla Nazimova, rumoured to be fond of seducing young actresses.[64]

- Pola Negri: Chaplin was involved in a very public relationship and engagement with the Polish actress, Negri, in 1922–23, after she arrived in Hollywood to star in films. The stormy on-off engagement was halted after about nine months, but in many ways it foreshadowed the modern stereotypes of Hollywood star relationships. Chaplin's public involvement with Negri was unique in his public life. By comparison he strove to keep his other romances during this period very discreet and private (usually without success). Many biographers have concluded the affair with Negri was largely for publicity purposes.

- Marion Davies: In 1924, during the time he was involved with the underage Lita Grey, Chaplin was rumoured to have had a fling with actress Davies, companion of William Randolph Hearst. Davies and Chaplin were both present on Hearst's yacht the weekend preceding the mysterious death of Thomas Harper Ince. Charlie allegedly tried to persuade her to leave Hearst and remain with him, but she refused and stayed by Hearst's side until his death in 1951. Chaplin made a rare cameo appearance in Davies' 1928 film Show People, and by some accounts supposedly continued an affair with her until 1931.

- Lita Grey: Chaplin first met Grey during the filming of The Kid. Three years later, at age 35, he became involved with the then 16-year-old Grey during preparations for The Gold Rush in which she was to star as the female lead. They married on 26 November 1924, after she became pregnant (a development that resulted in her being removed from the cast of the film). They had two sons, the actors Charles Chaplin, Jr. (1925–1968) and Sydney Chaplin (1926–2009). The marriage was a disaster, with the couple hopelessly mismatched. The couple divorced on 22 August 1927.[65] Their extraordinarily bitter divorce had Chaplin paying Grey a then-record-breaking US$825,000 settlement, on top of almost one million dollars in legal costs. The stress of the sensational divorce, compounded by a federal tax dispute, allegedly turned his hair white. The Chaplin biographer Joyce Milton asserted in Tramp: The Life of Charlie Chaplin that the Grey-Chaplin marriage was the inspiration for Vladimir Nabokov's 1950s novel Lolita.

- Merna Kennedy: Lita Grey's friend, Kennedy was a dancer who Chaplin hired as the lead actress in The Circus (1928). It is rumoured that the two had an affair during shooting. Grey used the rumoured infidelity in her divorce proceedings.

- Georgia Hale was Lita Grey's replacement on The Gold Rush. In the documentary series, Unknown Chaplin, (directed and written by film historians Kevin Brownlow and David Gill), Hale, in a 1980s interview states that she had idolised Chaplin since childhood and that the then-19-year-old actress and Chaplin began an affair that continued for several years, which she details in her memoir, Charlie Chaplin: Intimate Close-Ups. During production of Chaplin's film City Lights in 1929–30, Hale, who by then was Chaplin's closest companion, was called in to replace Virginia Cherrill as the flower girl. Seven minutes of test footage survives from this recasting, and is included on the 2003 DVD release of the film, but economics forced Chaplin to rehire Cherrill. In discussing the situation in Unknown Chaplin, Hale states that her relationship with Chaplin was as strong as ever during filming. Their romance apparently ended sometime after Chaplin's return from his world tour in 1933.

- Louise Brooks was a chorine in the Ziegfeld Follies when she met Chaplin. He had gone to New York for the opening there of The Gold Rush. For two months in the summer of 1925, the two cavorted together at the Ritz, and with film financier A.C. Blumenthal and Brooks' fellow Ziegfeld girl Peggy Fears in Blumenthal's penthouse suite at the Ambassador Hotel. Brooks was with Chaplin when he spent four hours watching a musician torture a violin in a Lower East Side restaurant, an act he would recreate in Limelight.

- May Reeves was originally hired to be Chaplin's secretary on his 1931–1932 extended trip to Europe, dealing mostly with reading his personal correspondence. She worked only one morning, and then was introduced to Chaplin, who was instantly infatuated with her. May became his constant companion and lover on the trip, much to the disgust of Chaplin's brother, Syd. After Reeves also became involved with Syd, Chaplin ended the relationship and she left his entourage. Reeves chronicled her short time with Chaplin in her book, "The Intimate Charlie Chaplin".

- Paulette Goddard: Chaplin and actress Goddard were involved in a romantic and professional relationship between 1932 and 1940, with Goddard living with Chaplin in his Beverly Hills home for most of this time. Chaplin gave her starring roles in Modern Times and The Great Dictator. Refusal to clarify their marital status is often claimed to have eliminated Goddard from final consideration for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind. After the relationship ended in 1940, Chaplin and Goddard made public statements that they had been secretly married in 1936; but these claims were likely a mutual effort to prevent any lasting damage to Goddard's career. In any case, their relationship ended amicably in 1942, with Goddard being granted a settlement. Goddard went on to a major career in films at Paramount in the 1940s, working several times with Cecil B. DeMille. Like Chaplin, she lived her later life in Switzerland, dying in 1990.

- Joan Barry (1920–1996): In 1942, Chaplin had a brief affair with Barry, whom he was considering for a starring role in a proposed film, but the relationship ended when she began harassing him and displaying signs of severe mental illness (not unlike his mother). Chaplin's brief involvement with Barry proved to be a nightmare for him. After having a child, she filed a paternity suit against him in 1943. Although blood tests proved Chaplin was not the father of Barry's child, Barry's attorney, Joseph Scott, convinced the court that the tests were inadmissible as evidence, and Chaplin was ordered to support the child. The injustice of the ruling later led to a change in California law to allow blood tests as evidence. Federal prosecutors also brought Mann Act charges against Chaplin related to Barry in 1944, of which he was acquitted.[66] Chaplin's public image in America was gravely damaged by these sensational trials.[40] Barry was institutionalised in 1953 after she was found walking the streets barefoot, carrying a pair of baby sandals and a child's ring, and murmuring: "This is magic".[67] Chaplin's second wife, Lita Grey, later asserted that Chaplin had paid corrupt government officials to tamper with the blood test results. She further stated that "there is no doubt that she [Carol Ann] was his child."[68]

- Oona O'Neill: During Chaplin's legal trouble over the Barry affair, he met O'Neill, daughter of Eugene O'Neill, and married her on 16 June 1943. He was fifty-four; she had just turned eighteen. The marriage produced eight children; their last child, Christopher, was born when Chaplin was 73 years old. Oona survived Chaplin by fourteen years, and died from pancreatic cancer in 1991.[69]

Children

Child Birth Death Chaplin's age

at time of birthMother Grandchildren Norman Spencer Chaplin 7 July 1919 10 July 1919 30 Mildred Harris Charles Spencer Chaplin, Jr.[70] 5 May 1925 20 March 1968 36 Lita Grey Susan Maree Chaplin (b 1959) Sydney Earle Chaplin 31 March 1926 3 March 2009 36 Stephan Chaplin (b 19xx) Carol Ann Barry Chaplin (Disputed) 2 October 1943 54 Joan Barry Unknown Geraldine Leigh Chaplin 31 July 1944 55 Oona O'Neill Shane Saura Chaplin (b 1974)

Oona Castilla Chaplin (b 1986)Michael John Chaplin 7 March 1946 56 Kathleen Chaplin (b. 1975)

Dolores Chaplin (b. 1979)

Carmen Chaplin (b 19xx)

George Chaplin (b 19xx)Josephine Hannah Chaplin 28 March 1949 59 Julien Ronet (b. 1980) Victoria Chaplin 19 May 1951 62 Aurélia Thiérrée (b. 1971)

James Thiérrée (b. 1974)Eugene Anthony Chaplin 23 August 1953 64 Kiera Chaplin (b. 1982) Jane Cecil Chaplin 23 May 1957 68 Orson Salkind (b. 1986)

Osceola Salkind (b. 1994)Annette Emily Chaplin 3 December 1959 70 Christopher James Chaplin 6 July 1962 73 Awards and recognition

Chaplin was knighted in 1975 at the age of 85 as a Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE) by Queen Elizabeth II.[71][72] The honour had been first proposed in 1931. Knighthood was suggested again in 1956, but was vetoed after a Foreign Office report raised concerns over Chaplin's purported "communist" views and his moral behaviour in marrying two 16-year-old girls; it was felt that honouring him would damage both the reputation of the British honours system and relations with the United States.[73]

Among other recognitions, Chaplin was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1970; that he had not been among those originally honoured in 1961 caused some controversy.[74] Chaplin's Swiss mansion is to be opened as a museum tracing his life from the music halls in London to Hollywood fame.[75][76]

A statue of Charlie Chaplin was made by John Doubleday, to stand in Leicester Square in London. It was unveiled by Sir Ralph Richardson in 1981.[77] A bronze statue of him is at Waterville, County Kerry.[78]

Academy Awards

Chaplin received three Academy Awards in his lifetime: one for Best Original Score, and two Honorary Awards. However, during his active years as a filmmaker, Chaplin expressed disdain for the Academy Awards; his son Charles Jr wrote that Chaplin invoked the ire of the Academy in the 1930s by jokingly using his 1929 Oscar as a doorstop.[79] This may help explain why City Lights and Modern Times, considered by several polls to be two of the greatest of all motion pictures,[80][81] were not nominated for a single Academy Award.

- The 1st Academy Awards ceremony: When the first Oscars were awarded on 16 May 1929, the voting audit procedures that now exists had not yet been put into place, and the categories were still very fluid. Chaplin's The Circus was set to be heavily recognised, as Chaplin had originally been nominated for Best Production, Best Director in a Comedy Picture, Best Actor and Best Writing (Original Story). However, the Academy decided to withdraw his name from all the competitive categories and instead give him a Special Award "for versatility and genius in acting, writing, directing and producing The Circus". The only other film to receive a Special Award that year was The Jazz Singer.[82]

- The 13th Academy Awards ceremony: In 1941, The Great Dictator was nominated for five awards, including two for Chaplin: Best Writing and Best Actor. Chaplin lost out on both counts. For writing, he lost to Preston Sturges for The Great McGinty, and for acting to James Stewart for The Philadelphia Story.

- The 20th Academy Awards ceremony: In 1948, Chaplin's screenplay for Monsieur Verdoux was nominated, but the award went instead to Sidney Sheldon for The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer.

- The 44th Academy Awards ceremony: Chaplin's second Oscar was awarded forty-three years after his first, in 1972. Chaplin came out of exile to accept the Honorary Award for "the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century". Stepping onto the stage of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Chaplin received the longest standing ovation in Academy Award history, lasting a full twelve minutes.[83]

- The 45th Academy Awards ceremony: In 1973, Chaplin's film Limelight was honoured with an Oscar for Best Original Score. Though the film had originally been released in 1952, due to Chaplin's political difficulties at the time, the film did not play for one week in Los Angeles, and thus did not meet the criterion for nomination until it was re-released in 1972.

Chaplin's American business partner, who helped promote and release his films in the U.S., was Mo Rothman (1919- 2011). Rothman is also credited with urging Chaplin to end his self-imposed exile and visit the U.S. to appear and be honored both by the Lincoln Center Film Society in New York and then at Hollywood's Academy Awards in 1972.[84]

Legacy

Chaplin's "tramp" character is possibly the most imitated on all levels of entertainment. Chaplin once entered a "Chaplin look-alike" competition and did not make the final round.[85][86] The influence of his 'Tramp' character could be seen on other artists and media providers. Beginning early on there were many tributes, and parodies made. E. C. Segar's 1916 comic strip "Charlie Chaplin's Comedy Capers" is an early example.[87] Segar's 'Chaplin' comics would later be collected in 1917 into five books, precursors of the later comic book format.[88] Two different animated cartoon series also starred 'Charlie' a tramp character, the first a series of nine shorts from 1916 by Movca Film Service.[89] And later ten films[90] by the Pat Sullivan Studio from 1918–1919, which would later use the 'Charlie/Charley' gestures to create Felix the Cat, the character made one later appearance in one of Felix's 1923 cartoons "Felix in Hollywood".[91]

- From 1917 to 1918, silent film actor Billy West made more than 20 films as a comedian precisely imitating Chaplin's tramp character, makeup and costume.[92]

- The third of composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann's 1929–30 composition Wachsfigurenkabinett: Fünf kleine Opern (Waxworks: Five Little Operas) is entitled 'Chaplin-Ford-Trot', and features the character of Charlie Chaplin (in a speaking rather than operatic role).

- Shree 420 and Awaara main characters are heavily influenced by The Tramp.

- Kamal Haasan moulded his character "Chaplin Chellappa" on Chaplin in the Tamil film Punnagai Mannan[93]

- In 1985, Chaplin was honoured with his image on a postage stamp of the United Kingdom, and in 1994 he appeared on a United States postage stamp designed by caricaturist Al Hirschfeld.

- John Woo directed a parody film of Chaplin's "The Kid" called Hua ji shi dai (1981), also known as "Laughing Times."

- A minor planet, 3623 Chaplin, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina in 1981, is named after Chaplin.[94]

- In 1992, a film was made about Chaplin's life entitled Chaplin, directed by Oscar-winner Richard Attenborough, and starring Robert Downey, Jr., in an Oscar-nominated performance, and Geraldine Chaplin playing the part of Charlie Chaplin's mother, her own grandmother.

- In 2001, British comedian Eddie Izzard played Chaplin in Peter Bogdanovich's film, The Cat's Meow, which speculated about the still-unsolved death of producer Thomas H. Ince during a yachting party thrown by William Randolph Hearst, of which Chaplin was a guest.

- On 15 April 2011, a day before his 122nd birthday anniversary, Google celebrated this with a special Google Doodle video on its global and other country-wide homepages.[95]

Filmography and current rights issues

Chaplin wrote, directed, and starred in dozens of feature films and short subjects. Highlights include The Immigrant (1917), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936), and The Great Dictator (1940), all of which have been selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry. Three of these films made the AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies and AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) lists: The Gold Rush, City Lights, and Modern Times.

A listing of the dozens of Chaplin films and alternate versions can be found in the Ted Okuda-David Maska book Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp. Thanks to The Chaplin Keystone Project, efforts to produce definitive versions of Chaplin's pre-1918 short films have come to a successful end: after ten years of research and clinical international cooperation work, 34 Keystone films have been fully restored and published in October 2010 on a 4-DVD box set. All twelve Mutual films were restored in 1975 by archivist David Shepard and Blackhawk Films, and new restorations with even more footage were released on DVD in 2006.

Today, nearly all of Chaplin's output is owned by Roy Export S.A.S. in Paris, which enforces the library's copyrights and decides how and when this material can be released. French company MK2 acts as worldwide distribution agent for the Export company. In the U.S. as of 2010, distribution is handled under license by Janus Films, with home video releases from Criterion Collection, affiliated with Janus.

See also

- List of people on the cover of Time magazine (1920s)

References

- ^ "Trivia for A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate (1923)". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://imdb.com/title/tt0014624/trivia. Retrieved 22 June 2007.

- ^ Obituary Variety Obituaries, 28 December 1977.

- ^ Blanke, David (2002). The 1910s. American popular culture through history (illustrated ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-313-31251-9.

- ^ Haupert, Michael (2006). The Entertainment Industry. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-313-32173-3.

- ^ Kelly, Shawna (2008). Aviators in Early Hollywood (illustrated ed.). Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7385-5902-5.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 STARS". American Film Institute. Wed, 16 June 1999. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080822055357/http://www.afi.com/tvevents/100years/stars.aspx. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Sieff, Martin.Washington Times -Books 21 December 2008

- ^ Walsh, John (25 November 2009). "The Big Question: Does Charlie Chaplin merit a museum in his honour, and what is his legacy? – News, People". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/news/the-big-question-does-charlie-chaplin-merit-a-museum-in-his-honour-and-what-is-his-legacy-1826871.html. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Lynn, Kenneth (1997). Charlie Chaplin and His Times (illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-684-80851-2.

- ^ Express & Star, 18 Feb 2011

- ^ Robinson, David (1983). Chaplin, the mirror of opinion (illustrated ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-253-21160-6.

- ^ Hancock, F., Ian (2002). We are the Romani People. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MG0ahVw-kdwC&lpg=PA129&ots=PiTKUOos0d&dq=Charlie%20Chaplin%20Romani&pg=PA129#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Charles Chaplin, Jr., with N. and M. Rau, My Father, Charlie Chaplin, Random House: New York,(1960), pages 7–8. Quoted in "The Religious Affiliation of Charlie Chaplin". Adherents.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.adherents.com/people/pc/Charlie_Chaplin.html.

- ^ Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography, page 19. Quoted in "The Religious Affiliation of Charlie Chaplin". Adherents.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.adherents.com/people/pc/Charlie_Chaplin.html.

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey (2 October 2003). Chaplin: genius of the cinema (illustrated ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8109-4532-6.

- ^ Robinson, David (21 August 1994). Chaplin: his life and art (revised ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-306-80600-1.

- ^ Robinson, David (21 August 1994). Chaplin: his life and art (revised ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-306-80600-1.

- ^ "PHOTO PAGES from CHAPLIN STAGE BY STAGE". www.charliechaplininmusichall.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.charliechaplininmusichall.com/photopages.html. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Eric L. Flom, Chaplin in the sound era: an analysis of the seven talkies, page 6. McFarland, 1997. ISBN 978-0-7864-0325-7. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=R9NuChpopoAC&pg=PA6&dq=The+Eight+Lancashire+Lads&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=1#v=onepage&q=The%20Eight%20Lancashire%20Lads&f=false. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Goncalves, Regina (2008). Einstein, Picasso, Agatha and Chaplin. Raleigh, NC: Lulu.com. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4092-1566-0.

- ^ Charles Chaplin My Autobiography, p. 91, Penguin UK, 2003, ISBN:0141011475

- ^ Robinson, David, Chaplin, His Life and Art (Da Capo Press, 1994), p. 60.

- ^ Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler, Charlie Chaplin and His Times (Simon & Schuster, 1997), pp. 210–11.

- ^ Chaplin, Charles (1964). My Autobiography. Penguin. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-0-14-101147-9.

- ^ Chaplin, Charles (1964). My Autobiography. Penguin. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-14-101147-9.

- ^ Fussell, Betty (1982). Mabel: Hollywood's First I Don't Care Girl. Limelight Edition. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-87910-158-9.

- ^ a b c d Chaplin, Charles (1964). My Autobiography. Penguin. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-14-101147-9.

- ^ a b "American Experience | Mary Pickford | People & Events". PBS. 25 December 1977. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/pickford/peopleevents/p_chaplin.html. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ a b Sutton, Caroline (1985). How Did They Do That? Wonders of the Far and Recent Past Explained. New York: Hilltown, Quill. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-688-05935-4.

- ^ Chaplin, Charles (1964). My Autobiography. p. 154.

- ^ Trescott, Jaqueline (13 June 2010). "The 'Thief' in festival's lineup is famous face, indeed: Chaplin's". Washington Post: p. E7.

- ^ Granlund, Nils (1957). Blondes, Brunettes and Bullets. New York: Van Rees Press, p. 53

- ^ Mrs. Fiske and the American Theatre by Archie Binns c. 1956 pages 195–196

- ^ Robert Hughes American Visions BBCTV

- ^ "Chaplin as a composer". CharlieChaplin.com. http://www.charliechaplin.com/biography/articles/205-Chaplin-as-a-composer.

- ^ Monday, 9 Feb. 1931 (9 February 1931). "Cinema: The New Pictures: Feb. 9, 1931". TIME. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,741027-1,00.html. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ a b c The Great Dictator at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ "The speech of the Great Dictator". Vagabundia.net. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.vagabundia.net/dictator.html. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "The Great Dictator (1940)". Movies.yahoo.com. http://movies.yahoo.com/movie/1800072595/awards. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b Whitfield, Stephen J., The Culture of the Cold War, page 187-192

- ^ "Names make news. Last week these names made this news". TIME. 27 April 1953. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,818302-2,00.html.

- ^ Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light (1996) American Masters, PBS

- ^ "Those Were the Days". Express and Star. http://www.expressandstar.com/days/1950-75/1975.html. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin Dead at 88; Made the Film an Art Form.". New York Times. 26 December 1977, Monday. http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/03/30/reviews/chaplin-obit.html. Retrieved 21 August 2007. "Charlie Chaplin, the poignant little tramp with the cane and comic walk who almost single-handedly elevated the novelty entertainment medium of motion pictures into art, died peacefully yesterday at his home in Switzerland. He was 88 years old."

- ^ "Henri Langlois (1914–1977) – Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=1234. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ "Chaplin Body Stolen From Swiss Grave. Vehicle Apparently Used. British Envoy 'Appalled'.". New York Times. 3 March 1978, Friday. "The body of Charlie Chaplin was stolen last night or early today from the grave where it was buried two months ago in a small cemetery in the Swiss village of Corsier-surVevey, overlooking the eastern end of Lake Geneva."

- ^ a b Unknown Chaplin at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Jones, Chuck. Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist. Avon Books, ISBN 978-0-380-71214-4)

- ^ everyHit.com search results

- ^ "Brooke Shields – Just Smile". TMZ.com. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.tmz.com/2009/07/07/brooke-shields-just-smile/. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ "British Record Charts". Petula Clark.net. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.petulaclark.net/chartsbritish.html. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Limelight (1952) – Awards

- ^ "Airplane's Dryden dies". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/newridersofthepurplesage/articles/story/6840281/airplanes_dryden_dies. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (5 November 2009). "Collector finds unseen Charlie Chaplin film in tin sold for £3.20 on eBay". The Guardian (London). Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2009/nov/05/charlie-chaplin-ebay-reel-tin. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "The Son of Charles and Hanna Thonstein". Filmography.co.il. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. http://www.filmography.co.il/en/entry/8/. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Harness, Kyp (2008). The art of Charlie Chaplin: a film-by-film analysis. McFarland & Co.. p. 163. ISBN 9780786431939. http://books.google.com/books?id=iu5kAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "The Religious Affiliation of Charlie Chaplin". Adherents.com. 2005. http://www.adherents.com/people/pc/Charlie_Chaplin.html.

- ^ Chaplin, Lita Grey; Vance, Jeffrey (1998). Wife of the life of the party. The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series. 61 (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8108-3432-3.

- ^ Mehran, Hooman. "Chaplin's writing and directing collaborators". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://chaplin.bfi.org.uk/programme/essays/collaborators.html. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Hotka, Thomas Carl (11 March 2010). West of the East Coast. AuthorHouse. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4490-8277-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ab6Dts2rH1wC&pg=PA143. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Kohn, Ingeborg (2005). Charlie Chaplin, Brightest star of silent films (First ed.). Rome, Italy: Portaparole. p. 21. ISBN 978-88-89421-14-7.

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey (2 October 2003). Chaplin: genius of the cinema (illustrated ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8109-4532-6.

- ^ a b Maland, Charles J. (1991). Chaplin and American Culture. Princeton University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-691-02860-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=hJhaiT7B04AC.

- ^ Zimmerman, Bonnie (1999). Lesbian Histories and Cultures. Routledge. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-8153-1920-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=0EUoCrFolGcC.

- ^ "International Herald Tribune. 23 August 2002. 1927:Chaplin Divorce Settled: In our pages: 100, 75 and 50 years ago". International Herald Tribune. 23 August 2002. http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/23/opinion/23iht-edold_ed3__57.html. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ "Mann & Woman". Time (magazine). 3 April 1944. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,850389,00.html. Retrieved 21 August 2007. "Auburn-haired Joan Barry, 24, who wandered from her native Detroit to New York to Hollywood in pursuit of a theatrical career, became a Chaplin protegee in the summer of 1941. She fitted into a familiar pattern. Chaplin signed her to a $75-a-week contract, began training her for a part in a projected picture. Two weeks after the contract was signed she became his mistress. Throughout the summer and autumn, Miss Barry testified last week, she visited the ardent actor five or six times a week. By midwinter her visits were down to "maybe three times a week". By late summer of 1942, Chaplin had decided that she was unsuited for his movie. Her contract ended."

- ^ "Just Like the Movies". Time (magazine). 17 August 1953. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,858217,00.html. Retrieved 21 August 2007. "Another Chaplin ex-protegee, 33-year-old Joan Barry, who won a 1946 paternity suit against the comedian, was admitted to Patton State Hospital (for the mentally ill) after she was found walking the streets barefoot, carrying a pair of baby sandals and a child's ring, and murmuring: "This is magic, my god"."

- ^ Cult Movies – Joan Barry: The Most (In)famous Actress to Never Appear on Screen

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin marries Oona O’Neill". New York: A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/6/16?catId=12. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Or Charles Spencer Chaplin III because his grandfather was called Charles Spencer Chaplin, Sr., and his father could have been called Charles Spencer Chaplin, Jr.

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 46444. p. 8. 1974-12-31. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ "Comic genius Chaplin is knighted". BBC. 4 March 1975. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/march/4/newsid_2794000/2794107.stm. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Reynolds, Paul (21 July 2002). "Chaplin knighthood blocked". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/2141391.stm. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Gregory Paul Williams, The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History, page 311. www.storyofhollywood.com, 2006, ISBN 978-0-9776299-0-9. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9W4R_CZtFe8C&pg=PA311&dq=charlie+chaplin+Hollywood+Walk+of+Fame&client=firefox-a&cd=6#v=onepage&q=charlie%20chaplin%20Hollywood%20Walk%20of%20Fame&f=false. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin museum to open in Swiss mansion". The Guardian (UK). 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2009/nov/23/charlie-chaplin-museum-swiss-mansion. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Chaplin". www.chaplinmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.chaplinmuseum.com/. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Haining 1982, p. 201.

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin Comedy Film Festival". http://www.chaplinfilmfestival.com/.

- ^ Chaplin, Charles (1960). My father, Charlie Chaplin. Random House.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1998). "List-o-Mania: Or, How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love American Movies". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.chicagoreader.com/movies/100best.html.

- ^ "The Complete List – ALL-TIME 100 Movies – TIME Magazine". TIME. 2005. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.time.com/time/2005/100movies/the_complete_list.html.

- ^ "History of the Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/about/history.html. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin prepares for return to United States after two decades". A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/charlie-chaplin-prepares-for-return-to-united-states-after-two-decades. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Vitello, Paul (26 September 2011). "Mo Rothman Dies at 92; Revived Interest in Charlie Chaplin". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/27/movies/mo-rothman-dies-at-92-revived-interest-in-charlie-chaplin.html?_r=1&hpw. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Howell, Melissa; Howell, Greg; Pierce, Seth (1 August 2010). Fusion: Where You and God Connect. Review and Herald Pub Assoc. p. 275. ISBN 9780828025478. http://books.google.com/books?id=yQtygrZJ_O4C&pg=PA275. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "You All Look Alike". Snopes.com. http://www.snopes.com/movies/actors/chaplin2.asp. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ Cope, Mike (2008). The Last of the Funnies: A Li'L Tall Tale about America's Favorite Art Form. CreateSpace. p. 63. ISBN 1438264127.

- ^ Inge, M. Thomas (1990). Comics as Culture. University Press of Mississippi. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-313-31251-9.

- ^ "The Internet Movie Database: Movca Film Service [us: Production Company – filmography"]. The Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/company/co0098778/. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ David A. Gerstein. "The Pre-Felix Pat Sullivan Studio Filmography". Golden Age Cartoons.com. http://felix.goldenagecartoons.com/prefelixfilms.html. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Canemaker, John (1996). Felix: The Twisted Tale of the World's Most Famous Cat. Da Capo Press. pp. 38, 78. ISBN 0306807319.

- ^ Louvish, Simon (2005). Stan and Ollie, the Roots of Comedy. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-312-32598-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=iSfU38xkO7AC.

- ^ "Timeless Classic Punnagai Mannan: Movie Review – Sri Lanka". Lankanewspapers.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. http://www.lankanewspapers.com/news/2006/12/10556_space.html. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 305. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. http://books.google.com/books?q=3623+Chaplin+1981+TC2.

- ^ "Google doodles a video honouring Charlie Chaplin". IBN Live. http://ibnlive.in.com/news/google-doodles-a-video-honouring-charlie-chaplin/149271-11.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

Further reading

- Charles Chaplin: My Autobiography. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

- Charles Chaplin: Die Geschichte meines Lebens. Fischer-Verlag, 1964. (germ.)

- Charlie Chaplin Die Wurzeln meiner Komik in: Jüdische Allgemeine Wochenzeitung, 3 March 1967, gekürzt: wieder ebd. 12.4. 2006, S. 54 (germ.)

- Chaplin: A Life by Stephen Weissman Arcade Publishing 2008.

- Charles Chaplin: My Life in Pictures. Bodley Head, 1974.

- Alistair Cooke: Six Men. Harmondsworth, 1978.

- S. Frind: Die Sprache als Propagandainstrument des Nationalsozialismus, in: Muttersprache, 76. Jg., 1966, S. 129–135. (germ.)

- Georgia Hale, Charlie Chaplin: Intimate Close-Ups, edited by Heather Kiernan. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 1995 and 1999. ISBN 978-1-57886-004-3 (1999 edition).

- Victor Klemperer: LTI – Notizbuch eines Philologen. Leipzig: Reclam, 1990. ISBN 978-3-379-00125-0; Frankfurt am Main (19. A.) 2004 (germ.)

- Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp, Ted Okuda & David Maska. iUniverse, New York, 2005.

- Chaplin: His Life and Art, David Robinson. McGraw-Hill, second edition 2001.

- Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema, Jeffrey Vance. Abrams, New York, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8109-4532-6

- Charlie Chaplin: A Photo Diary, Michel Comte & Sam Stourdze. Steidl, first edition, hardcover, 359pp, ISBN 978-3-88243-792-8, 2002.

- Chaplin in Pictures, Sam Stourdze (ed.), texts by Patrice Blouin, Christian Delage and Sam Stourdze, NBC Editions, ISBN 978-2-913986-03-9, 2005.

- Double Exposure: Charlie Chaplin as Author and Celebrity, Jonathan Goldman. M/C Journal 7.5.

- Charlie Chaplin's World of Comedy, Wes D. Gehring, 1980.

External links

- Charlie Chaplin at the Internet Movie Database

- Charles Chaplin at the TCM Movie Database

- Charlie Chaplin at AllRovi

- Charlie Chaplin Website

- Charlie Chaplin Comedy Film Festival Website

- The Charlie Chaplin Archive

- Chaplin A Life: 40 Photo-Essays

- Films by, about or starring Charlie Chaplin at the Internet Archive

- Obituary, NY Times, 26 December 1977 Chaplin's Little Tramp, an Everyman Trying to Gild Cage of Life, Enthralled World

- The TIME 100: Charlie Chaplin Archived, May 2011.

- Charlie Chaplin at Find a Grave

Hannah Chaplin's children Charlie Chaplin's wives Charlie Chaplin's children Norman Chaplin · Charles Chaplin, Jr. · Sydney Chaplin · Carol Ann Barry Chaplin (Disputed) · Geraldine Chaplin · Michael Chaplin · Josephine Chaplin · Victoria Chaplin · Eugene Chaplin · Jane Chaplin · Annette Chaplin · Christopher ChaplinCharlie Chaplin's grandchildren include Susan Chaplin · Stephan Chaplin · Shane Saura Chaplin · Oona Castilla Chaplin · Kathleen Chaplin · Dolores Chaplin · Carmen Chaplin · George Chaplin · Julien Ronet · Aurélia Thiérrée · James Thiérrée · Kiera Chaplin · Orson Salkind · Osceola SalkindCharlie Chaplin's great-grandchildren include Tamara Chaplin · Laurissa Newton · Allison Newton · Tyler Newton · Casey NewtonFilm Society of Lincoln Center Gala Tribute Honorees Charlie Chaplin (1972) · Fred Astaire (1973) · Alfred Hitchcock (1974) · Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman (1975) · George Cukor (1978) · Bob Hope (1979) · John Huston (1980) · Barbara Stanwyck (1981) · Billy Wilder (1982) · Laurence Olivier (1983) · Claudette Colbert (1984) · Federico Fellini (1985) · Elizabeth Taylor (1986) · Alec Guinness (1987) · Yves Montand (1988) · Bette Davis (1989) · James Stewart (1990) · Audrey Hepburn (1991) · Gregory Peck (1992) · Jack Lemmon (1993) · Robert Altman (1994) · Shirley MacLaine (1995) · Clint Eastwood (1996) · Sean Connery (1997) · Martin Scorsese (1998) · Mike Nichols (1999) · Al Pacino (2000) · Jane Fonda (2001) · Francis Ford Coppola (2002) · Susan Sarandon (2003) · Michael Caine (2004) · Dustin Hoffman (2005) · Jessica Lange (2006) · Diane Keaton (2007) · Meryl Streep (2008) · Tom Hanks (2009) · Michael Douglas (2010) · Sidney Poitier (2011)

Academy Award for Best Original Score (1961–1980) Henry Mancini/Saul Chaplin, Johnny Green, Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal (1961) · Maurice Jarre/Ray Heindorf (1962) · John Addison/Andre Previn (1963) · Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman/Andre Previn (1964) · Maurice Jarre/Irwin Kostal (1965) · John Barry/Ken Thorne (1966) · Elmer Bernstein/Alfred Newman and Ken Darby (1967) · John Barry/Johnny Green (1968) · Burt Bacharach/Lennie Hayton and Lionel Newman (1969) · Francis Lai/The Beatles (1970) · Michel Legrand/John Williams (1971) · Charlie Chaplin, Raymond Rasch and Larry Russell/Ralph Burns (1972) · Marvin Hamlisch/Marvin Hamlisch (1973) · Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola/Nelson Riddle (1974) · John Williams/Leonard Rosenman (1975) · Jerry Goldsmith/Leonard Rosenman (1976) · John Williams/Jonathan Tunick (1977) · Giorgio Moroder/Joe Renzetti (1978) · Georges Delerue/Ralph Burns (1979) · Michael Gore (1980)

Complete list · (1934–1940) · (1941–1960) · (1961–1980) · (1981–2000) · (2001–2020) AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars Male Legends Humphrey Bogart • Cary Grant • James Stewart • Marlon Brando • Fred Astaire • Henry Fonda • Clark Gable • James Cagney • Spencer Tracy • Charlie Chaplin • Gary Cooper • Gregory Peck • John Wayne • Laurence Olivier • Gene Kelly • Orson Welles • Kirk Douglas • James Dean • Burt Lancaster • The Marx Brothers • Buster Keaton • Sidney Poitier • Robert Mitchum • Edward G. Robinson • William Holden

Female Legends Katharine Hepburn • Bette Davis • Audrey Hepburn • Ingrid Bergman • Greta Garbo • Marilyn Monroe • Elizabeth Taylor • Judy Garland • Marlene Dietrich • Joan Crawford • Barbara Stanwyck • Claudette Colbert • Grace Kelly • Ginger Rogers • Mae West • Vivien Leigh • Lillian Gish • Shirley Temple • Rita Hayworth • Lauren Bacall • Sophia Loren • Jean Harlow • Carole Lombard • Mary Pickford • Ava Gardner

Categories:- 1889 births

- 1977 deaths

- 19th-century English people

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Actors awarded British knighthoods

- Actors from London

- Autobiographers

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- British expatriates in the United States

- British Romani people

- Charlie Chaplin

- Cinema pioneers

- English agnostics

- English child actors

- English comedians

- English expatriates in Switzerland

- English film actors

- English film directors

- English screenwriters

- English silent film actors

- English socialists

- Erasmus Prize winners

- Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- McCarthyism

- Mimes

- Music hall performers

- Romani actors

- Romani film directors

- Short film directors

- Silent film comedians

- Slapstick comedians

- Vaudeville performers

- 20th-century British people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.