- Eugene O'Neill

-

For other uses, see Eugene O'Neill (disambiguation).

Eugene O'Neill

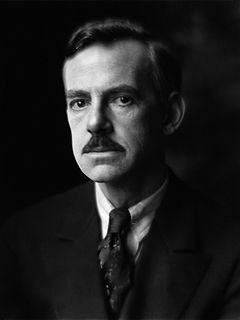

Portrait of O'Neill by Alice BoughtonBorn Eugene Gladstone O'Neill

October 16, 1888

New York City, USDied November 27, 1953 (aged 65)

Boston, Massachusetts, USOccupation Playwright Nationality United States Notable award(s) Nobel Prize in Literature (1936)

Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1920, 1922, 1928, 1957)Spouse(s) Kathleen Jenkins (1909–1912)

Agnes Boulton (1918–1929)

Carlotta Monterey (1929–1953)Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in Literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into American drama techniques of realism earlier associated with Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, and Swedish playwright August Strindberg. His plays were among the first to include speeches in American vernacular and involve characters on the fringes of society, where they struggle to maintain their hopes and aspirations, but ultimately slide into disillusionment and despair. O'Neill wrote only one well-known comedy (Ah, Wilderness!).[1][2] Nearly all of his other plays involve some degree of tragedy and personal pessimism.

Contents

Early years

O'Neill was born in a Broadway hotel room in Longacre Square (now Times Square), in the Barrett Hotel. The site is now a Starbucks (1500 Broadway, Northeast corner of 43rd & Broadway); a commemorative plaque is posted on the outside wall with the inscription: "Eugene O'Neill, October 16, 1888 ~ November 27, 1953 America's greatest playwright was born on this site then called Barrett Hotel, Presented by Circle in the Square."[3]

He was the son of Irish immigrant actor James O'Neill and Mary Ellen Quinlan. Because of his father's profession, O'Neill was sent to a Catholic boarding school where he found his only solace in books. O'Neill spent his summers in New London, Connecticut. After being suspended from Princeton University, he spent several years at sea, during which he suffered from depression and alcoholism. O'Neill's parents and elder brother Jamie (who drank himself to death at the age of 45) died within three years of one another, not long after he had begun to make his mark in the theater. Despite his depression he had a deep love for the sea, and it became a prominent theme in many of his plays, several of which are set onboard ships like the ones that he worked on.

Career

After his experience in 1912–13 at a sanatorium where he was recovering from tuberculosis, he decided to devote himself full-time to writing plays (the events immediately prior to going to the sanatorium are dramatized in his masterpiece, Long Day's Journey into Night). O'Neill had previously been employed by the New London Telegraph, writing poetry as well as reporting.

During the 1910s O'Neill was a regular on the Greenwich Village literary scene, where he also befriended many radicals, most notably Communist Labor Party founder John Reed. O'Neill also had a brief romantic relationship with Reed's wife, writer Louise Bryant. O'Neill was portrayed by Jack Nicholson in the 1981 film Reds about the life of John Reed.

His involvement with the Provincetown Players began in mid-1916. O'Neill is said to have arrived for the summer in Provincetown with "a trunk full of plays." Susan Glaspell describes what was probably the first ever reading of Bound East for Cardiff which took place in the living room of Glaspell and her husband George Cram Cook's home on Commercial Street, adjacent to the wharf (pictured) that was used by the Players for their theater. Glaspell writes in The Road to the Temple, "So Gene took Bound East for Cardiff out of his trunk, and Freddie Burt read it to us, Gene staying out in the dining-room while reading went on. He was not left alone in the dining-room when the reading had finished."[4] The Provincetown Players performed many of O'Neill's early works in their theaters both in Provincetown and on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. Some of these early plays began downtown and then moved to Broadway.

O'Neill's first published play, Beyond the Horizon, opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. His first major hit was The Emperor Jones, which ran on Broadway in 1920 and obliquely commented on the U.S. occupation of Haiti that was a topic of debate in that year's presidential election.[5] His best-known plays include Anna Christie (Pulitzer Prize 1922), Desire Under the Elms (1924), Strange Interlude (Pulitzer Prize 1928), Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), and his only well-known comedy, Ah, Wilderness!,[2][6] a wistful re-imagining of his youth as he wished it had been. In 1936 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. After a ten-year pause, O'Neill's now-renowned play The Iceman Cometh was produced in 1946. The following year's A Moon for the Misbegotten failed, and did not gain recognition as being among his best works until decades later.

He was also part of the modern movement to revive the classical heroic mask from ancient Greek theatre and Japanese Noh theatre in some of his plays, such as The Great God Brown and Lazarus Laughed.[7]

O'Neill was very interested in the Faust theme, especially in the 1920s.[8]

Family life

O'Neill was married to Kathleen Jenkins from October 2, 1909 to 1912, during which time they had one son, Eugene O'Neill, Jr. (1910–1950). In 1917, O'Neill met Agnes Boulton, a successful writer of commercial fiction, and they married on April 12, 1918. The years of their marriage—during which the couple had two children, Shane and Oona—are described vividly in her 1958 memoir Part of a Long Story. They divorced in 1929, after O'Neill abandoned Boulton and the children for the actress Carlotta Monterey (born San Francisco, California, December 28, 1888; died Westwood, New Jersey, November 18, 1970). O'Neill and Carlotta married less than a month after he officially divorced his previous wife.[9]

O'Neill in the mid-1930s. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936

O'Neill in the mid-1930s. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936

In 1929, O'Neill and Monterey moved to the Loire Valley in central France, where they lived in the Château du Plessis in Saint-Antoine-du-Rocher, Indre-et-Loire. During the early 1930s they returned to the United States and lived in Sea Island, Georgia, at a house called Casa Genotta. He moved to Danville, California in 1937 and lived there until 1944. His house there, Tao House, is today the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site.

In their first years together, Monterey organized O'Neill's life, enabling him to devote himself to writing. She later became addicted to potassium bromide, and the marriage deteriorated, resulting in a number of separations. O'Neill needed her, and she needed him.[editorializing] Although they separated several times, they never divorced.

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director and producer Charlie Chaplin when she was 18 and Chaplin was 54. He never saw Oona again.

He also had distant relationships with his sons, Eugene, Jr., a Yale classicist who suffered from alcoholism and committed suicide in 1950 at the age of 40, and Shane O'Neill, a heroin addict who also committed suicide.

Child Date of birth Date of death Notes Eugene O'Neill, Jr 1910 1950 Shane O'Neill 1918 1977 Oona O'Neill 14/05/1925 27/09/1991 Illness and death

O'Neill stamp issued in 1967

O'Neill stamp issued in 1967

After suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe Parkinsons-like tremor in his hands which made it impossible for him to write during the last 10 years of his life; he had tried using dictation but found himself unable to compose in that way. While at Tao House, O’Neill had intended to write a cycle of 11 plays chronicling an American family since the 1800s. Only two of these, A Touch of the Poet and More Stately Mansions were ever completed. As his health worsened, O’Neill lost inspiration for the project and wrote three largely autobiographical plays, The Iceman Cometh, Long Day's Journey Into Night, and A Moon for the Misbegotten. He managed to complete Moon for the Misbegotten in 1943, just before leaving Tao House and losing his ability to write. Drafts of many other uncompleted plays were destroyed by Carlotta at Eugene’s request.

O'Neill died in Room 401 of the Sheraton Hotel on Bay State Road in Boston, on November 27, 1953, at the age of 65. As he was dying, he, in a barely audible whisper, spoke his last words: "I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room, and God damn it, died in a hotel room."[10] The building would later become the Shelton Hall dormitory at Boston University. There is an urban legend perpetuated by students that O'Neill's spirit haunts the room and dormitory. A revised analysis of his autopsy report shows that, contrary to the previous diagnosis, he did not have Parkinson's disease, but a late-onset cerebellar cortical atrophy.[11]

Dr. Harry Kozol, the lead prosecuting expert of the Patty Hearst trial, treated O'Neill during these last years of ailment. He also was present for the death and announced the fact to the public.[12]

He is interred in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood.

Although his written instructions had stipulated that it not be made public until 25 years after his death, in 1956 Carlotta arranged for his autobiographical masterpiece Long Day's Journey Into Night to be published, and produced on stage to tremendous critical acclaim and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957. This last play is widely considered to be his finest. Other posthumously-published works include A Touch of the Poet (1958) and More Stately Mansions (1967).

The United States Postal Service honored O'Neill with a Prominent Americans series (1965–1978) $1 postage stamp.

Museums and collections

O'Neill's home in New London, Monte Cristo Cottage, was made a National Historic Landmark in 1971. His home in Danville, California, near San Francisco, was preserved as the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site in 1976.

Connecticut College maintains the Louis Sheaffer Collection, consisting of material collected by the O'Neill biographer. The principal collection of O'Neill papers is at Yale University. The Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut fosters the development of new plays under his name.

Work

See also: Category:Plays by Eugene O'NeillFull-length plays

- Bread and Butter, 1914

- Servitude, 1914

- The Personal Equation, 1915

- Now I Ask You, 1916

- Beyond the Horizon, 1918 - Pulitzer Prize, 1920

- The Straw, 1919

- Chris Christophersen, 1919

- Gold, 1920

- Anna Christie, 1920 - Pulitzer Prize, 1922

- The Emperor Jones, 1920

- Diff'rent, 1921

- The First Man, 1922

- The Hairy Ape, 1922

- The Fountain, 1923

- Marco Millions, 1923–25

- All God's Chillun Got Wings, 1924

- Welded, 1924

- Desire Under the Elms, 1925

- Lazarus Laughed, 1925–26

- The Great God Brown, 1926

- Strange Interlude, 1928 - Pulitzer Prize

- Dynamo, 1929

- Mourning Becomes Electra, 1931

- Ah, Wilderness!, 1933

- Days Without End, 1933

- The Iceman Cometh, written 1939, published 1940, first performed 1946

- Hughie, written 1941, first performed 1959

- Long Day's Journey Into Night, written 1941, first performed 1956 - Pulitzer Prize 1957

- A Moon for the Misbegotten, written 1941–1943, first performed 1947

- A Touch of the Poet, completed in 1942, first performed 1958

- More Stately Mansions, second draft found in O'Neill's papers, first performed 1967

- The Calms of Capricorn, published in 1983

One-act plays

The Glencairn Plays, all of which feature characters on the fictional ship Glencairn -- filmed together as The Long Voyage Home:

- Bound East for Cardiff, 1914

- In The Zone, 1917

- The Long Voyage Home, 1917

- Moon of the Caribbees, 1918

Other one-act plays include:

Other works

- The Last Will and Testament of An Extremely Distinguished Dog, 1940. Written to comfort Carlotta as their "child" Blemie was approaching his death in December 1940.[15]

See also

- The Eugene O'Neill Award

References

- ^ The New York Times, August 25, 2003: 'Next year Playwrights Theater will present an unproduced O'Neill comedy, Now I Ask You, a comic spin on Ibsen's Hedda Gabler."

- ^ a b c The Eugene O'Neill Foundation newsletter: "Now I Ask You, along with The Movie Man, ... is the only surviving comedy from O’Neill’s early years."

- ^ Arthur Gelb (1957-10-17). "O'Neill's Birthplace Is Marked By Plaque at Times Square Site". The New York Times: p. 35. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00910F73B5C127A93C5A8178BD95F438585F9. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ^ Susan Glaspell, (1927), The Road to the Temple, Frederick A. Stokes, New York, 2nd ed. 1941, p. 255

- ^ Renda, Mary (2001). Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 198–212. ISBN 0807849383.

- ^ The New York Times, Aug. 25, 2003: 'Next year Playwrights Theater will present an unproduced O'Neill comedy, Now I Ask You, a comic spin on Ibsen's Hedda Gabler."

- ^ Smith, Susan Harris (1984). Masks in Modern Drama. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 66–70, 106–08, 131–36, index S124. ISBN 0520050959.

- ^ Floyd, Virginia (1985). "Chapter 2". Eugene O'Neill: A New Assessment. New York: F. Ungar Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 0804422060.

- ^ "Eugene O'Neill Wed to Miss Monterey". The New York Times: p. 9. 1929-07-24. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F60D10F6345D14738DDDAD0A94DF405B898EF1D3. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ^ Sheaffer, Louis. O'Neill: Son and Artist. Little, Brown & Co., 1973 ISBN 0-316-78337-4

- ^ "Eugene O'Neill - What Went Wrong?". Neuroscience for Kids. April 22, 2000. http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/oneill.html. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ "Eugene O'Neill Dies of Pneumonia; Playwright, 65, Won Nobel Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ Title as in original typescript and title page of Modern Library edition

- ^ ""Exorcism". Yale U. Library Acquires Lost Play by Eugene O'Neill. Chronicle of Higher Education. October 19, 2011. http://chronicle.com/blogs/pageview/yale-u-library-acquires-lost-play-by-eugene-oneill/29541?sid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ O'Neill, Eugene; Adrienne Yorinks (1999). The Last Will and Testament of an Extremely Distinguished Dog (First ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0805061703. http://www.eoneill.com/texts/blemie/contents.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

Further reading

- O'Neill, Eugene; Bogard, Travis (1988). Complete Plays 1913–1920. The Library of America. 40. New York: Literary Classics. ISBN 9780940450486.

- O'Neill, Eugene; Bogard, Travis (1988). Complete Plays 1920–1931. The Library of America. 41. New York: Literary Classics. ISBN 9780940450493.

- O'Neill, Eugene; Bogard, Travis (1988). Complete Plays 1932–1943. The Library of America. 42. New York: Literary Classics. ISBN 9780940450509.

- Black, Stephen A. (2002). Eugene O'Neill: Beyond Mourning and Tragedy. Yale University press. ISBN 0300093993.

- Clark, Barrett H. (November 1932). "Aeschylus and O'Neill". The English Journal (The English Journal, Vol. 21, No. 9) XXI (9): 699–710. doi:10.2307/804473. JSTOR 804473.

- Floyd, Virginia (editor) (1979). Eugene O'Neill: A World View. Frederick Unger. ISBN 0804422044.

- Floyd, Virginia (1985). The Plays of Eugene O'Neill: A New Assessment. Frederick Unger. ISBN 0804422060.

- Gelb, Arthur & Barbara (2000). O'Neill: Life with Monte Christo. Applause/Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-399-14912-0.

- Sheaffer, Louis (2002 [1968]). O'Neill Volume I: Son and Playwright. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0815412436.

- Sheaffer, Louis (1999 [1973]). O'Neill Volume II: Son and Artist. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0815412444.

- Wainscott, Ronald H. (1988). Staging O'Neill: The Experimental Years. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04152-7.

- Winther, Sophus Keith (1934). Eugene O'Neill: A Critical Study. New York: Random House. OCLC 900356.

- Clark, Barrett H. (1926). Eugene O'Neill: The Man and His Plays. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

External links

- Eugene O'Neill official website

- Casa Genotta official website

- Eugene O'Neill at Find a Grave

- Eugene O'Neill at the Internet Broadway Database

- Eugene O'Neill at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Eugene O'Neill at the Internet Movie Database

- Eugene O'Neill at the Notable Names Database

- Eugene O'Neil Autobiography at the Nobel Foundation

- The Iceman Cometh: A Study Guide

- Works by Eugene O'Neill at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Eugene O'Neill at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site

- American Experience - Eugene O'Neill: A Documentary Film on PBS

- Works by Eugene O'Neill (public domain in Canada)

- Haunted by Eugene O'Neill Article in BU Today, Sept 29 2009

Eugene O'Neill public domain audiobooks from LibriVox

Eugene O'Neill public domain audiobooks from LibriVox

Awards and achievements Preceded by

Warren S. StoneCover of Time Magazine

March 17, 1924Succeeded by

Raymond PoincaréNobel Laureates in Literature (1926–1950) - Grazia Deledda (1926)

- Henri Bergson (1927)

- Sigrid Undset (1928)

- Thomas Mann (1929)

- Sinclair Lewis (1930)

- Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1931)

- John Galsworthy (1932)

- Ivan Bunin (1933)

- Luigi Pirandello (1934)

- Eugene O'Neill (1936)

- Roger Martin du Gard (1937)

- Pearl S. Buck (1938)

- Frans Eemil Sillanpää (1939)

- Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (1944)

- Gabriela Mistral (1945)

- Hermann Hesse (1946)

- André Gide (1947)

- T. S. Eliot (1948)

- William Faulkner (1949)

- Bertrand Russell (1950)

- Complete list

- (1901–1925)

- (1926–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1918–25) - Jesse Lynch Williams (1918)

- Eugene O'Neill (1920)

- Zona Gale (1921)

- Eugene O'Neill (1922)

- Owen Davis (1923)

- Hatcher Hughes (1924)

- Sidney Howard (1925)

- Complete list

- (1918–1925)

- (1926–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1926–50) - George Kelly (1926)

- Paul Green (1927)

- Eugene O'Neill (1928)

- Elmer Rice (1929)

- Marc Connelly (1930)

- Susan Glaspell (1931)

- George S. Kaufman / Morrie Ryskind / Ira Gershwin (1932)

- Maxwell Anderson (1933)

- Sidney Kingsley (1934)

- Zoe Akins (1935)

- Robert E. Sherwood (1936)

- Moss Hart / George S. Kaufman (1937)

- Thornton Wilder (1938)

- Robert E. Sherwood (1939)

- William Saroyan (1940)

- Robert E. Sherwood (1941)

- Thornton Wilder (1943)

- Mary Chase (1945)

- Russel Crouse / Howard Lindsay (1946)

- Tennessee Williams (1948)

- Arthur Miller (1949)

- Richard Rodgers / Oscar Hammerstein II / Joshua Logan (1950)

- Complete list

- (1918–1925)

- (1926–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1951–75) - Joseph Kramm (1952)

- William Inge (1953)

- John Patrick (1954)

- Tennessee Williams (1955)

- Albert Hackett / Frances Goodrich (1956)

- Eugene O'Neill (1957)

- Ketti Frings (1958)

- Archibald MacLeish (1959)

- Jerome Weidman / George Abbott / Jerry Bock / Sheldon Harnick (1960)

- Tad Mosel (1961)

- Frank Loesser / Abe Burrows (1962)

- Frank D. Gilroy (1965)

- Edward Albee (1967)

- Howard Sackler (1969)

- Charles Gordone (1970)

- Paul Zindel (1971)

- Jason Miller (1973)

- Edward Albee (1975)

- Complete list

- (1918–1925)

- (1926–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Categories:- 1888 births

- 1953 deaths

- American dramatists and playwrights

- American Nobel laureates

- Expressionist dramatists and playwrights

- American people of Irish descent

- American writers of Irish descent

- Modernist drama, theatre and performance

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Laurence Olivier Award winners

- People from New London, Connecticut

- People from Greenwich Village, New York

- People from New York City

- People with Parkinson's disease

- People from Ridgefield, Connecticut

- Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners

- Tony Award winners

- Irish American history

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.