- Long Day's Journey into Night

-

For the film, see Long Day's Journey Into Night (1962 film).

Long Day's Journey Into Night

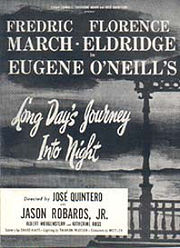

Original window card, 1956Written by Eugene O'Neill Characters Mary Cavan Tyrone

James Tyrone

Edmund Tyrone

James Tyrone, Jr.

CathleenDate premiered 2 February 1956 Place premiered Royal Dramatic Theatre

Stockholm, SwedenOriginal language English Subject an autobiographical account of his explosive homelife, fused by a drug-addicted mother. Genre Drama Setting the home of the Tyrones, August 1912 IBDB profile Long Day's Journey Into Night is a 1956 drama in four acts written by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. The play is widely considered to be his masterwork. O'Neill posthumously received the 1957 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for the work.

Contents

Summary

The action covers a fateful, heart-rending day from around 8:30 am to midnight, in August 1912 at the seaside Connecticut home of the Tyrones - the semi-autobiographical representations of O'Neill himself, his older brother, and their parents at their home, Monte Cristo Cottage.

One theme of the play is addiction and the resulting dysfunction of the family. All three males are alcoholics and Mary is addicted to morphine. In the play the characters conceal, blame, resent, regret, accuse and deny in an escalating cycle of conflict with occasional desperate and half-sincere attempts at affection, encouragement and consolation.

Synopsis

Characters

- James Tyrone, Sr.

- (65 yrs) Looks ten years younger and is about five feet eight but appears taller due to his military-like posture and bearing. He is broad shouldered and deep chested and remarkably good looking for his age with light brown eyes. His speech and movement are those of a classical actor with a studied technique, but he is unpretentious and not temperamental at all with "inclinations still close to his humble beginnings and Irish farmer forbears". His attire is somewhat threadbare and shabby. He wears his clothing to the limit of usefulness. He has been a healthy man his entire life and is free of hang ups and anxieties but has "streaks of sentimental melancholy and rare flashes of intuitive sensibility". He smokes cigars and dislikes being referred to as the 'Old Man" by his sons.

- Mary Cavan Tyrone

- (54 yrs) The wife and mother of the family who lapses between self-delusion and the haze of her morphine addiction. She is medium height with a young graceful figure, a trifle plump with distinctly Irish facial features. She was once extremely pretty and is still striking. She wears no make-up and her hair is thick, white and perfectly coiffed and she has large, dark, almost black, eyes. She has a soft and attractive voice with a "touch of Irish lilt when she is merry".

- James “Jamie”, Jr.

- (33 yrs) The older son, has thinning hair, an aquiline nose and shows signs of premature disintegration. He has a habitual expression of cynicism. He resembles his father. "On the rare occasions when he smiles without sneering, his personality possesses the remnant of a humorous, romantic, irresponsible Irish charm – the beguiling ne'er-do-well, with a strain of the sentimentally poetic". He is attractive to women and popular with men. He is an actor like his father but has difficulty finding work due to a reputation for being an irresponsible, womanizing alcoholic. His father and he argue a great deal about this.

- Edmund

- (23 yrs) The younger and more intellectually and poetically inclined son, is thin and wiry, he looks like both his parents but more like his mother. He has her big dark eyes and hypersensitive mouth in a long narrow Irish face with dark brown hair and red highlights from the sun. Like his mother, he is extremely nervous. He is in bad health and his cheeks are sunken. Later he is diagnosed with tuberculosis. He is politically inclined with socialist leanings. He travelled the world by working in the merchant navy and may have caught tuberculosis while abroad.

- Cathleen

- "The second girl", is the summer maid. She is a "buxom Irish peasant", in her early twenties with red cheeks, black hair and blue eyes. She is "amiable, ignorant, clumsy with a well-meaning stupidity".

Several characters are referenced in the play but do not appear on stage:

- Eugene Tyrone

- A deceased son of the Tyrones who died of measles in infancy. Mary believes that he was infected by her son James who was seven at the time and had been told not to enter the infant's room but disobeyed.

- Bridget

- A cook

- McGuire

- A real estate agent who has advised Tyrone in the past.

- Shaughnessy

- A tenant on a farm owned by Tyrone.

- Harker

- A friend of Tyrone, "the Standard Oil millionaire", owns a neighboring farm to Shaughnessy with whom he gets into conflicts.

- Doctor Hardy

- Tyrone's physician whom the other family members don't think much of.

- Captain Turner

- The Tyrones' neighbor.

- Smythe

- A garage assistant whom Tyrone hired as a chauffeur for Mary. Mary suspects he is intentionally damaging the car to provide work for the garage.

- The mistress

- A woman with whom Tyrone had had an affair before his marriage, who had later sued him causing Mary to be shunned by her friends as someone with undesirable social connections.

- Mary's father

- Died of consumption.

- Tyrone's parents and siblings

- The family immigrated to the United States when Tyrone was 8 years old. Two years later the father abandoned the family and returned to Ireland where he died after ingesting rat poison. It was suspected suicide but Tyrone refuses to believe that. He had two older brothers and three sisters.

Act I

James Tyrone is an aging actor (65 yrs) who had bought a 'vehicle' play for himself and had established a reputation based on this one role with which he had toured for years. Although it had served him well financially, by the time of the opening of the play, he is resentful of the fact that he has become so identified with this character that it has severely limited his scope and opportunity as an actor. He is a wealthy man, but his money is all tied up in property which he hangs on to in spite of impending financial hardship. His dress and appearance are showing signs of his strained financial circumstances but he moves and speaks with the hallmark attributes of a classical actor of the declamatory tradition in spite of his shabby attire.

His wife Mary has recently returned from treatment for morphine addiction and has put on weight as a result. She is looking much healthier than the family has been accustomed to, and they remark frequently on her improved appearance. She still retains the haggard facial features of a long-time addict. In common with many recovering addicts, she is restless and anxious and suffers from insomnia, not made any easier by her husband and children's loud snoring. When Edmund, her younger son, hears her moving around at night and entering the spare bedroom, he becomes very alarmed. It was the room that his mother used to go to get 'high'. He questions her about it indirectly. She reassures him that she just went there to get away from her husband's snoring.

In addition to Mary's problems, the whole family is worried about Edmund's constant coughing. The family fears that he might have tuberculosis, and this anxiety has placed them all under additional stress. They are anxiously awaiting the diagnosis of his condition. Edmund is more concerned about the effect a positive diagnosis might have on his mother than for himself. The constant possibility of a relapse worries him sicker than he already is. Once again, he indirectly speaks to his mother about her addiction. He asks her to "promise not to worry yourself sick and to take care of yourself". "Of course I promise you", she protests, but then adds "with a sad bitterness", "But I suppose you're remembering I've promised before on my word of honor".

Act II

Jamie and Edmund taunt each other about stealing their father's alcohol and watering it down so he won't notice. They speak about Mary's conduct. Jamie berates Edmund for leaving their mother unsupervised. Edmund berates Jamie for being suspicious. Both, however, are deeply concerned that their mother's morphine abuse may have resurfaced. Jamie points out to Edmund that they had concealed their mother's addiction from him for ten years. Jamie explains to Edmund that his naiveté about the nature of the disease was understandable but deluded. They discuss the upcoming results of Edmund's tests for tuberculosis, and Jamie tells Edmund to prepare for the worst.

Their mother appears. She is distraught about Edmund's coughing, which he tries to suppress so as not to alarm her, fearing anything that might trigger her addiction again. When Edmund accepts his mother's excuse that she had been upstairs so long because she had been "lying down", Jamie looks at them both contemptuously. Mary notices and starts becoming defensive and belligerent, berating Jamie for his cynicism and disrespect for his parents. Jamie is quick to point out that the only reason he has survived as an actor is through his father's influence in the business.

Mary speaks of her frustration with their summer home, its impermanence and shabbiness, and her husband's indifference to his surroundings. With irony, she alludes to her belief that this air of detachment may be the very reason he has tolerated her addiction for so long. This frightens Edmund, who is trying desperately to hang on to his belief in normality while faced with two emotionally horrific problems at once. Finally, unable to tolerate the way Jamie is looking at her, she asks him angrily why he is doing it. "You know!", he shoots back, and tells her to take a look at her glazed eyes in the mirror.

Act III

The third act opens with Mary and Cathleen returning home from their drive to the drugstore where Mary has sent Cathleen in to purchase her morphine prescription. Not wanting to be alone, Mary does not allow Cathleen to go to the kitchen to finish dinner and offers her a drink instead. Mary does most of the talking and discusses her hatred of the fog and particularly the foghorn and her husband’s obvious obsession with money. It is obvious that Mary has already taken some of her “prescription.” She talks about her past in a Catholic convent and the promise she once had as a pianist and the fact that it was once thought that she might become a nun. She also makes it clear that while she fell in love with her husband from the time she met him, she had never taken to the theatre crowd. She shows her arthritic hands to Cathleen and explains that the pain in her hands is why she needs her prescription – an explanation which is untrue and transparent to Cathleen. When Mary dozes off under the influence of the morphine, Cathleen exits to prepare dinner. Mary awakes and begins to have bitter memories about how much she loved her life before she met her husband. She also decides that her prayers as a dope fiend are not being heard by the Virgin, but still decides to go upstairs to get more drugs, but before she can do so, her son, Edmund, and her husband, Tyrone, return home. Although both men are drunk, they both realize that she is back on morphine although Mary attempts to act as if she is not. Jamie, the other son, has not returned home, but has elected instead to continue drinking and to visit the local whorehouse. After calling Jamie, "hopeless failure" Mary warns that his bad influence will drag his brother down as well. After seeing the condition that Mary is in, her husband expresses the regret that he bothered to come home and attempts to ignore her as she continues her remarks which include blaming him for Jamie’s drinking, noting that the Irish are notably stupid drunks. Then, as so often happens in the play, Mary and Tyrone try to get over their animosity and attempt to express their love for one another by remembering happier days. When Tyrone goes to the basement to get another bottle of whiskey, Mary continues to talk with her son, Edmund.

When Edmund reveals that he has consumption (tuberculosis), Mary refuses to believe it, and attempts to discredit Dr. Hardy. She accuses Edmund of attempting to get more attention by blowing everything out of proportion. In retaliation. Edmund reminds his mother that her own father died of tuberculosis, and then, before exiting, he adds how difficult it is to have a "dope fiend for a mother." By herself, Mary admits that she needs more drugs and hopes that someday she will “accidentally” overdose, because she knows that if she did so on purpose, the Virgin would never forgive her. When Tyrone comes back with more alcohol he notes that there was evidence that Jamie had attempted to pick the locks to the whiskey cabinet in the cellar as he had done before. Mary ignores this and bursts out that she is afraid that Edmund is going to die. She also confides to Tyrone that Edmund does not love her because of her drug problem. When Tyrone attempts to console her, Mary again accuses herself for giving birth to Edmund, who appears to have been conceived to replace a baby Mary and James lost before Edmund’s birth. When Cathleen announces dinner, Mary indicates that she is not hungry and is going to lie down. Tyrone goes in to dinner all alone, knowing that Mary is really going upstairs to get more drugs.

Act IV

At midnight, Edmund comes home to find his father playing solitaire. While the two fight and drink, they also have an intimate, tender conversation. Tyrone explains his stinginess, and also reveals that he ruined his career by staying in an acting job for money. After so many years playing the same part, he lost his talent for versatility. Edmund talks to his father about sailing, and hopes to be a great writer. They hear Jamie coming home drunk, and Tyrone leaves to avoid fighting. Jamie and Edmund converse, and Jamie confesses that although he loves Edmund more than anyone else, he wants him to fail. Jamie passes out. When Tyrone returns, Jamie wakes up, and they fight anew. Mary comes downstairs, by now so drugged she can barely recognize them. She carries her wedding gown, lost completely in her past, as the men watch in horror.

History of the play

Upon its completion in 1942, O'Neill had a sealed copy of the play placed in the document vault of publisher Random House, and instructed that it not be published until 25 years after his death. A formal contract to that effect was drawn up in 1945. However, O'Neill's third wife Carlotta Monterey transferred the rights of the play to Yale University, skirting the agreement. The copyright page of Yale editions of the play states the conditions of Carlotta's gift:

All royalties from the sale of the Yale editions of this book go to Yale University for the benefit of the Eugene O'Neill Collection, for the purchase of books in the field of drama, and for the establishment of Eugene O'Neill Scholarships in the Yale School of Drama.The play was first published in 1956, three years after its author's death.

Autobiographical content

Monte Cristo Cottage, setting of the play, in 2008

Monte Cristo Cottage, setting of the play, in 2008

In key aspects, the play closely parallels Eugene O'Neill's own life. The location, a summer home in Connecticut, corresponds to the family home, Monte Cristo Cottage, in New London, Connecticut (the small town of the play), and in real life the cottage is today made up as it may have appeared in the play. The family corresponds to the O'Neill family, which was Irish-American, with three name changes: the family name "O'Neill" is changed to "Tyrone," the name of the earldom granted to Conn O'Neill by Henry VIII; the names of the second and third sons are reversed ("Eugene" with "Edmund" – in real life, Eugene was the third (youngest) child, who corresponds to the character of "Edmund" in the play); and O'Neill's mother, in real life Mary Ellen "Ella" Quinlan, is renamed to Mary Cavan. The ages are all the actual ages of the O'Neill family in August 1912.

In real life, Eugene O'Neill's father, James O'Neill, was a promising young actor in his youth, as was the father in the play, and did share the stage with Edwin Booth, who is mentioned in the play. He achieved commercial success in the title role to Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo, playing the title role about 6000 times, and he had been criticized as "selling out".[1]

Eugene's mother Mary did attend a Catholic school in the Midwest (Middle West), Saint Mary's College, of Notre Dame, Indiana. Subsequent to the date when the play is set (1912), but prior to the play's writing (1941–42), Eugene's older brother Jamie did drink himself to death (c. 1923).

As to Eugene himself, by 1912 he had attended a renowned university (Princeton), spent several years at sea, and suffered from depression and alcoholism, and did contribute to the local newspaper, the New London Telegraph, writing poetry as well as reporting. He did go to a sanatorium in 1912–13 due to suffering from tuberculosis (consumption), whereupon he devoted himself to playwriting. The events in the play are thus set immediately prior to Eugene beginning his career in earnest.

Productions

Premiere productions

Long Day's Journey Into Night was first performed by the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, Sweden. During O'Neill's lifetime, the Swedish people had embraced his work to a far greater extent than had any other nation, including his own. Thus, the play had its world premiere in Stockholm on February 2, 1956, in a production directed by Bengt Ekerot, with the cast of Lars Hanson (James Tyrone), Inga Tidblad (Mary Tyrone), Ulf Palme (James Tyrone, Jr.), Jarl Kulle (Edmund Tyrone) and Catrin Westerlund (Cathleen, the serving-maid or "second girl" as O'Neill's script dubs her). The premiere and production were very successful, and the directing and acting critically acclaimed.

The Broadway debut of Long Day's Journey Into Night took place at the Helen Hayes Theatre on 7 November 1956, shortly after its American premiere at New Haven's Shubert Theatre.[2] The production was directed by José Quintero, and its cast included Fredric March (James Tyrone), Florence Eldridge (Mary Tyrone), Jason Robards, Jr. (“Jamie” Tyrone), Bradford Dillman (Edmund), and Katharine Ross (Cathleen). The production won the Tony Award for Best Play and Best Actor in a Play (Fredric March), and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play of the season.

The play’s first production in the United Kingdom came in 1958, opening first in Edinburgh, Scotland and then moving to the Globe Theatre in London’s West End. It was directed again by Quintero, and the cast included Anthony Quayle (Tyrone), Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies (Mary), Ian Bannen (Jamie), Alan Bates (Edmund), and Etain O'Dell (Cathleen).

Other notable productions

- 1970: Memorial Art Center (Georgia), GA; with Robert Foxworth (Tyrone), Gerald Richards (Jamie), Jo Van Fleet (Mary), directed by Michael Howard.

- 1971: Promenade Theatre (Broadway), New York; with Robert Ryan (Tyrone), Geraldine Fitzgerald (Mary), Stacy Keach (Jamie), James Naughton (Edmund), and Paddy Croft (Cathleen), directed by Arvin Brown.

- 1971: National Theatre, London; with Laurence Olivier (Tyrone), Constance Cummings (Mary), Denis Quilley (Jamie), Ronald Pickup (Edmund), and Jo Maxwell-Muller (Cathleen), directed by Michael Blakemore. This production would be adapted into a televised version, which aired 10 March 1973; the cast was as above, excepting the substitution of Maureen Lipman (Cathleen). The TV version was directed by Michael Blakemore and Peter Wood. Laurence Olivier won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role.

- 1976: Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, NY; with Jason Robards, Jr. (Tyrone), Zoe Caldwell (Mary), Kevin Conway (Jamie), Michael Moriarty (Edmund), and Lindsay Crouse (Cathleen), directed by Jason Robards, Jr.

- 1982: ABC-TV; with an all African-American cast of Earle Hyman (Tyrone), Ruby Dee (Mary), Thommie Blackwell (Jamie), and Peter Francis-James (Edmund).

- 1986: Broadhurst Theatre (Broadway), New York; with Jack Lemmon (Tyrone), Bethel Leslie (Mary), Kevin Spacey (Jamie), Peter Gallagher (Edmund), and Jodie Lynne McClintock (Cathleen), directed by Jonathan Miller. A television version of this production was aired in 1987.

- 1988: Neil Simon Theatre (Broadway), New York; with Jason Robards, Jr. (Tyrone), Colleen Dewhurst (Mary), Jamey Sheridan (Jamie), Campbell Scott (Edmund), and Jane Macfie (Cathleen), directed by José Quintero. This production ran in repertory with O’Neill’s play, Ah, Wilderness!, (in which the author’s youth and family are depicted as he wished they had been), featuring the same actors. Dewhurst was also the real-life mother of Campbell Scott (by her marriage to actor George C. Scott).

- 1988: Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm; with Jarl Kulle (Tyrone), Bibi Andersson (Mary), Thommy Berggren (Jamie), Peter Stormare (Edmund), and Kicki Bramberg (Cathleen), directed by Ingmar Bergman.

- 1991: National Theatre, London; with Timothy West (Tyrone), Prunella Scales (Mary), Sean McGinley (Jamie), Stephen Dillane (Edmund), and Geraldine Fitzgerald (Cathleen), directed by Howard Davies.

- 1995: Stratford Festival of Canada, Stratford, Ontario; with William Hutt (Tyrone), Martha Henry (Mary), Peter Donaldson (Jamie), Tom McCamus (Edmund), and Martha Burns (Cathleen), directed by Diana Leblanc. This production was made into a film in 1996, directed by David Wellington.

- 2000: Lyric Theatre, London; with Jessica Lange (Mary), Charles Dance (Tyrone), Paul Rudd (Jamie), Paul Nicholls (Edmund), and Olivia Colman (Cathleen).

- 2003: Plymouth Theatre (Broadway), New York; with Brian Dennehy (Tyrone), Vanessa Redgrave (Mary), Philip Seymour Hoffman (Jamie), Robert Sean Leonard (Edmund), and Fiana Toibin (Cathleen), directed by Robert Falls.

- 2005 Centaur Theater, Montreal; with Albert Millaire (Tyrone), Rosemary Dunsmore (Mary), Alain Goulem (James Jr), Brendan Murray (Edmund), Laura Teasdale (Cathleen), directed by David Latham

- 2007: Druid Theatre, Galway; with James Cromwell (Tyrone), Marie Mullen (Mary), Aidan Kelly (Jamie), Michael Esper (Edmund), and Maude Fahy (Cathleen), directed by Garry Hynes.

- 2010: Co-production with Sydney Theatre & Artists Repertory Theatre, Sydney Theatre Company; with William Hurt (Tyrone), Luke Mullins (Edmund), Robyn Nevin (Mary), Emily Russell (Cathleen) and Todd Van Voris (Jamie), directed by Andrew Upton.

- 2010: Riksteatret (Norway); with Bjørn Sundquist (Tyrone), Liv Ullmann (Mary), Anders Baasmo Christiansen (Jamie), Pål Sverre Valheim Hagen (Edmund) and Viktoria Winge (Cathleen), directed by Stein Winge.

Film adaptations

Main article: Long Day's Journey into Night (1962 film)The play was made into a 1962 film, starring Katharine Hepburn as Mary, Ralph Richardson as Tyrone, Jason Robards, Jr. as Jamie, Dean Stockwell as Edmund, and Jeanne Barr as Cathleen. The movie was directed by Sidney Lumet. At that year’s Cannes Film Festival Richardson, Robards and Stockwell all received Best Actor awards, and Hepburn was named Best Actress. Hepburn’s performance later drew a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress.

London's National Theatre production was adapted into a film, televised on March 10, 1973, with Laurence Olivier (Tyrone), Constance Cummings (Mary), Denis Quilley (Jamie), Ronald Pickup (Edmund), and Maureen Lipman (Cathleen), directed by Michael Blakemore and Peter Wood. Olivier won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role.

The 1982 made for ABC-TV film, with an all African-American cast of Earle Hyman (Tyrone), Ruby Dee (Mary), Thommie Blackwell (Jamie), and Peter Francis-James (Edmund).

The 1987 made for TV film starred Kevin Spacey as Jamie, Peter Gallagher as Edmund, Jack Lemmon as James Tyrone, Bethel Leslie as Mary, and Jodie Lynne McClintock as Cathleen. Lemmon was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actor in Mini-Series or Made-for-TV Movie the following year.

In 1996, another adaptation, directed by Canadian director David Wellington, starred William Hutt as Tyrone, Martha Henry as Mary, Peter Donaldson as Jamie, Tom McCamus as Edmund and Martha Burns as Cathleen. The same cast had previously performed the play at Canada's Stratford Festival; Wellington essentially filmed the stage production without significant changes. The film swept the acting awards at the 17th Genie Awards, winning awards for Hutt, Henry, Donaldson and Burns.

Awards and nominations

- Awards

- 1957 Pulitzer Prize for Drama

- 1957 Tony Award for Best Play

- 2003 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival of a Play

- 2003 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play

- Nominations

- 1986 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival

- 1989 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival

References

- ^ Eaton, Walter Prichard (1910). The American Stage of Today. New York, NY: P.F. Collier & Son.

- ^ "Shubert Theater:". CAPA New Haven. 2008. http://www.capa.com/newhaven/venues/shubert_history.php. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- "Long Day's Journey Into Night". eOneill.com. 2008. http://www.eoneill.com/artifacts/Long_Days_Journey.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

Further reading

- O'Neill, Eugene Gladstone (1991). Long Day's Journey Into Night (Recent Edition ed.). London: Nick Hern Books. ISBN 978-1854591029.

- O'Neill, Eugene Gladstone (1956). Long Day's Journey Into Night (First edition ed.). New Haven. ISBN 250174075.

External links

- Long Day's Journey into Night at the Internet Broadway Database

- Long Day's Journey into Night at the Internet off-Broadway Database

Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival of a Play (2001–2025) The Best Man (2001) · Private Lives (2002) · Long Day's Journey into Night (2003) · Henry IV (2004) · Twelve Angry Men (2005) · Awake and Sing! (2006) · Journey's End (2007) · Boeing-Boeing (2008) · The Norman Conquests (2009) · A View from the Bridge / Fences (2010) · The Normal Heart (2011)

Complete list · (1976–2000) · (2001–2025) Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1951–1975) - The Shrike (1952)

- Picnic (1953)

- The Teahouse of the August Moon (1954)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955)

- The Diary of Anne Frank (1956)

- Long Day's Journey into Night (1957)

- Look Homeward, Angel (1958)

- J.B. (1959)

- Fiorello! (1960)

- All the Way Home (1961)

- How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (1962)

- The Subject Was Roses (1965)

- A Delicate Balance (1967)

- The Great White Hope (1969)

- No Place to be Somebody (1970)

- The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1971)

- That Championship Season (1973)

- Seascape (1975)

- Complete list

- (1918–1925)

- (1926–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Tony Award for Best Play (1948–1975) Mister Roberts (1948) · Death of a Salesman (1949) · The Cocktail Party (1950) · The Rose Tattoo (1951) · The Fourposter (1952) · The Crucible (1953) · The Teahouse of the August Moon (1954) · The Desperate Hours (1955) · The Diary of Anne Frank (1956) · Long Day's Journey into Night (1957) · Sunrise at Campobello (1958) · J.B. (1959) · The Miracle Worker (1960) · Becket (1961) · A Man for All Seasons (1962) · Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1963) · Luther (1964) · The Subject Was Roses (1965) · Marat/Sade (1966) · The Homecoming (1967) · Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1968) · The Great White Hope (1969) · Borstal Boy (1970) · Sleuth (1971) · Sticks and Bones (1972) · That Championship Season (1973) · The River Niger (1974) · Equus (1975)

Complete list · (1948–1975) · (1976–2000) · (2001–2025) Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play (2001–2025) One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (2001) · Private Lives (2002) · Long Day's Journey into Night (2003) · Henry IV (2004) · Glengarry Glen Ross (2005) · Awake and Sing! (2006) · Journey's End (2007) · Boeing-Boeing (2008) · The Norman Conquests (2009) · Fences (2010) · The Normal Heart (2011)

Complete list · (1994–2000) · (2001–2025) Categories:- 1956 plays

- Broadway plays

- Plays by Eugene O'Neill

- Drama Desk Award winning plays

- Off-Broadway plays

- Autobiographical plays

- Plays based on actual events

- Pulitzer Prize for Drama

- Theatre World Award winners

- Tony Award winning plays

- West End plays

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.