- History of Pakistan

-

History of Pakistan

also see History of

AJK · Balochistan · G&B · KPK · Punjab · Sindh Timeline of PakistanBC Soanian People ~500,000 Mehrgarh Culture 7000–2800 Indus Valley Civilization 3300–1750 Vedic Civilization 2000–600 Indo-Greek Kingdom 250 BC–11 AD Gandhara Civilization 200 BC–1000 AD Indo-Scythian Kingdom 200 BC–400 AD AD Indo-Parthian Kingdom 21–130 Kushan Empire 30–375 Indo-Sassanids 240–410 Hephthalite 420–567 Rai Dynasty 489–632 Umayyad Caliphate 661–750 Ghaznavid Empire 963–1187 Mamluk dynasty 1206–1290 Khilji dynasty 1290–1320 Tughlaq dynasty 1320–1413 Sayyid dynasty 1414–1451 Lodhi dynasty 1451–1526 Mughal Empire 1526–1858 Durrani Empire 1747–1823 Sikh Confederacy 1733–1805 Sikh Empire 1799–1849 British Indian Empire 1849–1947 Dominion of Pakistan 1947–1956 Islamic Republic since 1956

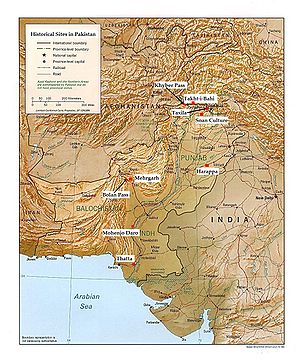

edit The 1st known inhabitants of the modern-day Pakistan region are believed to have been the Soanian (Homo erectus), who settled in the Soan Valley and Riwat almost 2 million years ago. Over the next several thousand years, the region would develop into various civilizations like Mehrgarh and the Indus Valley Civilization. Prior to the independence as a modern state in 1947, the country was both independent and under various colonial empires throughout different time periods. The region's ancient history also includes some of the oldest empires from the subcontinent[1] and some of its major civilizations.[2][3][4][5] Thus, Pakistan is in fact a multi-regional state and not a South Asian state actor only; its history if analyzed in depth would prove the point. By the 18th century the land was incorporated into British India. The political history of the nation began with the birth of the All India Muslim League in 1906 to protect Muslim interests, amid neglect and under-representation, in case the British Raj decided to grant local self-rule. On the 29 December 1930, Sir Muhammad Iqbal called for an autonomous state in "northwestern India for Indian Muslims".[6] The League rose to popularity in the late 1930s. Muhammad Ali Jinnah espoused the Two Nation Theory and led the League to adopt the Lahore Resolution[7] of 1940, demanding the formation of independent states in the East and the West of British India. Eventually, a united Pakistan with its wings – West Pakistan and East Pakistan – gained independence from the British, on 14 August 1947. After a civil war, the Bengal region of East Pakistan, separated at a considerable distance from the rest of Pakistan, became the independent state of Bangladesh in 1971.

Pakistan declared itself an Islamic republic on adoption of a constitution in 1956, but the civilian rule was stalled by the 1958 military coup d'etat by Ayub Khan, who ruled during a period of internal instability and a second war with India in 1965. Economic grievances and political disenfranchisement in East Pakistan led to violent political tensions and army repression, escalating into civil war[8] followed by the third war with India. Pakistan's defeat in the war ultimately led to the secession of East Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh.[9]

Civilian rule resumed from 1972 to 1977 under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, until he was deposed by General Zia-ul-Haq, who became the country's third military president. Pakistan's secular policies were replaced by the Islamic Shariah legal code, which increased religious influences on the civil service and the military. With the death of Zia-ul-Haq in 1988, Benazir Bhutto, daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was elected as the first female Prime Minister of Pakistan. Over the next decade, she alternated power with Nawaz Sharif, as the country's political and economic situation worsened. Military tensions in the Kargil conflict[10] with India were followed by a 1999 coup d'état in which General Pervez Musharraf assumed executive powers.

In 2001, Musharraf named himself President after the resignation of Rafiq Tarar. In the 2002 Parliamentary Elections, Musharraf transferred executive powers to newly elected Prime Minister Zafarullah Khan Jamali, who was succeeded in the 2004 by Shaukat Aziz. On 15 November 2007 the National Assembly completed its term and a caretaker government was appointed with the former Chairman of The Senate, Muhammad Mian Soomro as Prime Minister. Following the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, that resulted in a series of important political developments, her husband Asif Ali Zardari was eventually elected as the new President in 2008.

Contents

Prehistory

Soanian Culture

The Soanian is an archaeological culture of the Lower Paleolithic (ca. 500,000 to 1,250,000 BC), contemporary to the Acheulean. It is named after the Soan Valley in the Sivalik Hills, near modern-day Islamabad/Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The bearers of this culture were Homo erectus. In Adiyala and Khasala[disambiguation needed

], about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) from Rawalpindi, on the bend of the Soan River hundreds of edged pebble tools were discovered. No human skeletons of this age have yet been found. In the Soan River Gorge many fossil bearing rocks are exposed on the surface. The 14 million year old fossils of gazelle, rhinoceros, crocodile, giraffe and rodents have been found there. Some of these fossils are on display at the Natural History Museum in Islamabad.

], about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) from Rawalpindi, on the bend of the Soan River hundreds of edged pebble tools were discovered. No human skeletons of this age have yet been found. In the Soan River Gorge many fossil bearing rocks are exposed on the surface. The 14 million year old fossils of gazelle, rhinoceros, crocodile, giraffe and rodents have been found there. Some of these fossils are on display at the Natural History Museum in Islamabad.Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh, (7000–5500 BCE), on the Kachi Plain of Balochistan, is an important Neolithic site discovered in 1974, with early evidence of farming and herding,[11] and dentistry.[1] Early residents lived in mud brick houses, stored grain in granaries, fashioned tools with copper ore, cultivated barley, wheat, jujubes and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. As the civilization progressed (5500–2600 BCE) residents began to engage in crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metalworking. The site was occupied continuously until 2600 BCE,[12] when climatic changes began to occur. Between 2600 and 2000 BCE, region became more arid and Mehrgarh was abandoned in favour of the Indus Valley,[13] where a new civilization was in the early stages of development.[14]

Indus Valley Civilization

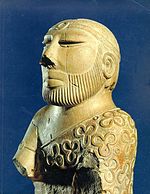

The Indus Valley Civilization developed between 3300–1700 BCE on the banks of the Indus River. At its peak, the civilisation hosted a population of approximately 5 million in hundreds of settlements extending as far as the Arabian Sea, present-day southern and eastern Afghanistan, southeastern Iran and the Himalayas.[15] Major urban centers were at Dholavira, Kalibangan, Harappa, Lothal, Mohenjo-daro, and Rakhigarhi, as well as an offshoot called the Kulli culture (2500–2000 BCE) in southern Balochistan, which had similar settlements, pottery and other artifacts. The civilization collapsed abruptly around 1700 BCE.

In the early part of the second millennium BCE, the Rigvedic civilization existed,[16] between the Sapta Sindhu and Ganges-Yamuna rivers.[17] The city of Taxila in northern Pakistan, became important to Vedic religion (and later in Buddhism).[18]

Early history

Vedic period

Main article: Vedic CivilizationThe Vedic period is characterized by Indo-Aryan culture associated with the texts of Vedas, sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed in Vedic Sanskrit. The Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts, next to those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. The Vedic period lasted from about 1500 to 500 BCE, laying the foundations of Hinduism and other cultural aspects of early Indian society.

Early Vedic society consisted of largely pastoral groups, with late Harappan urbanization having been abandoned.[19] After the time of the Rigveda, Aryan society became increasingly agricultural and was socially organized around the four varnas, or social classes. In addition to the Vedas, the principal texts of Hinduism, the core themes of the Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahabharata are said to have their ultimate origins during this period.[20] The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture in archaeological contexts.[21]

The Kuru kingdom[22] corresponds to the Black and Red Ware and Painted Grey Ware cultures and to the beginning of the Iron Age in India, around 1000 BCE, as well as with the composition of the Atharvaveda, the first Indian text to mention iron, as śyāma ayas, literally "black metal." The Painted Grey Ware culture spanned much of northern India from about 1100 to 600 BCE.[21] The Vedic Period also established republics such as Vaishali, which existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE. The later part of this period corresponds with an increasing movement away from the previous tribal system towards the establishment of kingdoms, called mahajanapadas.

Achaemenid Empire

Much of modern-day Pakistan was under the Achaemenid Empire. Taxila became a satrapy during the reign of Darius the Great.

Much of modern-day Pakistan was under the Achaemenid Empire. Taxila became a satrapy during the reign of Darius the Great.

The Indus plains formed the most populous and richest satrapy of the Persian Achaemenid Empire for almost two centuries, starting from the reign of Darius the Great (522–485 BCE).[23] Its heritage influenced the region, e.g., adoption of Aramaic script, which the Achaemenids used for the Persian language; but after the end of Achaemenid rule, other scripts became more popular, such as Kharoṣṭhī (derived from Aramaic) and Greek.

Greek Invasion

Crushing the Persian Achaemenid empire, Alexander the Great, the Greek king from Macedonia, eventually invaded the region of modern Pakistan and conquered much of the Punjab region. After defeating King Porus in the fierce Battle of the Hydaspes (modern day Jhelum), his battle weary troops refused to advance further into India[24] to engage the formidable army of Nanda Dynasty and its vanguard of trampling elephants, new monstorities to the invaders. Therefore, Alexander proceeded southwest along the Indus valley.[25] Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms before marching his army westward across the inhospitable Makran desert towards modern Iran. Alexander founded several new Macedonian and Greek settlements in Gandhara, Punjab and Sindh. During that time, many Greeks settled all over in Pakistan, initiating interaction between the culture of Hellenistic Greece and the region's prevalent Hindu, Zoroastrian and Buddhist cultures.

After Alexander's untimely death in 323 BC, his Diadochi (generals) divided the empire among themselves, with the Macedonian warlord Seleucus setting up the Seleucid Kingdom, which included the Indus plain.[26] Around 250 BCE, the eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.

Maurya Empire

Modern day Pakistan was conquered by the Maurya Empire, which was led by Chandragupta Maurya of Magadha (modern day Bihar in India), who overthrew the powerful Nanda Dynasty of Magadha. They were Indians who were focusing on taking over Central Asia. Seleucus is said to have reach a peace treaty with Chandragupta by giving control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to him upon intermarriage and 500 elephants.

Alexander took these away from the Indo-Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[27]Mauryans were followers of Hinduism and Buddhism. With an area of 5,000,000 km2, it was one of the world's largest empires in its time, and the largest ever in the Indian subcontinent. At its greatest extent, the empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the Himalayas, and to the east stretching into what is now Assam province in India. To the west, it conquered beyond modern Pakistan, annexing Balochistan, south eastern parts of Iran and much of what is now Afghanistan, including the modern Herat[28] and Kandahar provinces. The Empire was expanded into India's central and southern regions by the emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara, but it excluded a small portion of unexplored tribal and forested regions near Kalinga (modern Orissa), till it was conquered by Ashoka. Its decline began 60 years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 BC with the foundation of the Sunga Dynasty in Magadha.

Under Chandragupta, the Mauryan Empire conquered the trans-Indus region, which was under Macedonian rule. Chandragupta then defeated the invasion led by Seleucus I, a Greek general from Alexander's army. Under Chandragupta and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture and economic activities, all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security.

After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia and Mediterranean Europe.[28]

Indo-Greek Kingdoms

Greco-Buddhism (or Græco-Buddhism) was the syncretism between the culture of Classical Greece and Buddhism in the then Gandhara region of modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE.[29] It influenced the artistic development of Buddhism, and in particular Mahayana Buddhism, before it spread to central and eastern Asia, from the 1st century CE onward. Demetrius (son of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus) invaded northern India in 180 BCE as far as Pataliputra and established an Indo-Greek kingdom. To the south, the Greeks captured Sindh and nearby coastal areas, completing the invasion by 175 BCE and confining the borders of Sunga's (Magadha Empire) to the east. Meanwhile, in Bactria, the usurper Eucratides killed Demetrius in a battle. Although the Indo-Greeks lost part of the Gangetic plain, their kingdom lasted nearly two centuries.

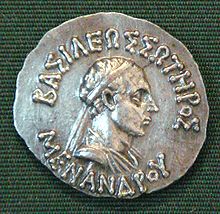

A coin of Menander I, who ruled the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of Bactria and the modern Pakistani provinces of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh.

A coin of Menander I, who ruled the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of Bactria and the modern Pakistani provinces of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh.

The Indo-Greek Menander I (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming a king shortly after his victory. His territories covered Panjshir and Kapisa in modern Afghanistan and extended to the Punjab region, with many tributaries to the south and east, possibly as far as Mathura. The capital Sagala (modern Sialkot) prospered greatly under Menander's rule and Menander is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors.[30] The classical Buddhist text Milinda Pañha praises Menander, saying there was "none equal to Milinda in all India".[31] His empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, Strato II, disappeared around 10 CE. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, fled from the Yuezhi invasion of Bactria and relocated to Gandhara, pushing the Indo-Greeks east of the Jhelum River. Various petty kings ruled into the early 1st century CE, until the conquests by the Scythians, Parthians and the Yuezhi, who founded the Kushan dynasty. The last known Indo-Greek ruler was Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, mentioned on a 1st century CE signet ring, bearing the Kharoṣṭhī inscription "Su Theodamasa" ("Su" was the Greek transliteration of the Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah" or "King")).

The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from southern Siberia to pakistan and Arachosia from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. Scythian tribes spread into the present-day Pakistan region and the Iranian plateau.

The Parni, a nomadic Central Asian tribe, invaded Parthia in the middle of the 3rd century BCE, drove away its Greek satraps — who had just then proclaimed independence from the Seleucids — and annexed much of the Indus region, thus founding an Arsacids dynasty of Sythian or Bactrian origin. Following the decline of the central Parthian authority after clashes with the Roman Empire, a local Parthian leader, Gondophares established the Indo-Parthian Kingdom in the 1st century CE. The kingdom was ruled from Taxila and covered much of modern southeast Afghanistan and Pakistan.[32] Christian writings claim that the Apostle Saint Thomas – an architect and skilled carpenter – had a long sojourn in the court of king Gondophares, had built a palace for the king at Taxila and had also ordained leaders for the Church before leaving for Indus Valley in a chariot, for sailing out to eventually reach Malabar Coast.

Kushan Empire

The Kushan kingdom was founded by King Heraios, and greatly expanded by his successor, Kujula Kadphises. Kadphises' son, Vima Takto conquered territory now in India, but lost much of the west of the kingdom to the Parthians. The fourth Kushan emperor, Kanishka I, (c. 127 CE) had a winter capital at Purushapura (Peshawar) and a summer capital at Kapisa (Bagram). The kingdom linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the Silk Road through the Indus valley. At its height, the empire extended from the Aral Sea to northern India, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and Rome. Kanishka convened a great Buddhist council in Taxila, marking the start of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its scission with Nikaya Buddhism. The art and culture of Gandhara — the best known expressions of the interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures — also continued over several centuries, until the 5th century CE White Hun invasions of Scythia. The travelogues of Chinese pilgrims Fa Xian (337 – ca.422 CE) and Huen Tsang (602/603–664 CE) describe the famed Buddhist seminary at Taxila and the status of Buddhism in the region of Pakistan in this period.

Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire existed approximately from 320 to 600 CE and covered much of the Indian Subcontinent, including Pakistan.[33] Founded by Maharaja Sri-Gupta, the dynasty was the model of a classical civilization[34] and was marked by extensive inventions and discoveries.[35][36]

The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent architectures, sculptures and paintings.[clarification needed][37][38][39] Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era.[clarification needed][40] Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural center and set the region up as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in Burma, Sri Lanka, Maritime Southeast Asia and Indochina.[41]

The empire gradually declined due in part to loss of territory and imperial authority caused by their own erstwhile feudatories, and from the invasion by the Hunas from Central Asia.[42] After the collapse of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, India was again ruled by numerous regional kingdoms. A minor line of the Gupta clan continued to rule Magadha after the disintegration of the empire. These Guptas were ultimately ousted by the Vardhana king Harsha, who established an empire in the first half of the 7th century.[citation needed]

Sassanid Empire

Over the next few centuries, while the Indo-Parthians and Kushans shared control of the Indus plain until the arrival of the White Huns, the Persian Sassanid Empire dominated the south and southwest. The mingling of Indian and Persian cultures in the region gave rise to the Indo-Sassanid culture, which flourished in Balochistan and western Punjab.

The White Huns, who seem to have been part of the predominantly Buddhist Hephthalite group, established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century, with their capital at Bamiyan. Led by the Hun military leader Toramana, they over-ran the northern region of Pakistan and made their capital at the city of Sakala, modern Sialkot in Pakistan, under Toramana's son, Emperor Mihirakula, who was a Saivite Hindu.

According to Arab chroniclers, the Rai Dynasty of Sindh (c. 489–632) arose after the end of Ror Dynasty. They were practitioners of Hinduism and Buddhism; they established a huge temple of Shiva in present-day Sukkur – derived from original Shankar – close to their capital in Al-ror.[43] At the time of Rai Diwaji (Devaditya), influence of the Rai-state exdended from Kashmir in the east, Makran and Debal (Karachi) port in the south, Kandahar, Sistan, Suleyman, Ferdan and Kikanan hills in the north.

Pāla Empire

Devapala}}

Main article: PalasThe Pāla's were a multifaith Bengali Hindu and Buddhist dynasty, which lasted for four centuries (750–1120 CE). The empire reached its peak under Dharmapala and Devapala to cover much of South Asia and beyond up to Kamboja (modern day Afghanistan.[citation needed] Followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism, they were responsible for the introduction of Mahayana Buddhism in Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, Myanmar and Maritime Southeast Asia, creation of temples and works of art and patronage of great universities formerly patronised by the Hindu king Harsha Vardhana.[44] The Palas had extensive trade as well as influence in Southeast Asia. The Pala Empire eventually disintegrated in the 12th century under the attack of the Hindu Sena dynasty.[citation needed]

Later Medieval Age

Arab Invasion

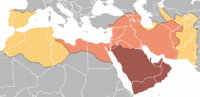

Although soon after conquering the Middle East from the long-established Byzantine empire Arab forces had reached the present western regions of Pakistan, during the period of Rashidun caliphacy, it was in 712 CE that a young Arab general called Muhammad bin Qasim conquered most of the Indus region for the Umayyad empire, to be made the "As-Sindh" province with its capital at Al-Mansurah, 72 km (45 mi) north of modern Hyderabad in Sindh. But the instability of the empire and the defeat in various wars with north Indian rulers including the Battle of Rajasthan, where the Hindu Rajput clans defeated the Umayyad Arabs, they were contained till only Sindh and southern Punjab. There was gradual conversion to Islam in the south, especially amongst the native Hindu and Buddhist majority, but in areas north of Multan, Hindus and Buddhists remained numerous.[45] By the end of 10th century CE, the region was ruled by several Hindu Shahi kings who would be subdued by the Ghaznavids.

In 997 CE, Mahmud of Ghazni, took over the Ghaznavid dynasty empire established by his father, Sebuktegin, a Turkic origin ruler. Starting from the city of Ghazni (now in Afghanistan), Mehmood conquered the bulk of Khorasan, marched on Peshawar against the Hindu Shahis in Kabul in 1005, and followed it by the conquests of Punjab (1007), deposed the Shia Ismaili rulers of Multan, (1011), Kashmir (1015) and Qanoch (1017). By the end of his reign in 1030, Mahmud's empire extended from Kurdistan in the west to the Yamuna river in the east, and the Ghaznavid dynasty lasted until 1187. Contemporary historians such as Abolfazl Beyhaqi and Ferdowsi described extensive building work in Lahore, as well as Mahmud's support and patronage of learning, literature and the arts.

Delhi Sultanate

In 1160, Muhammad Ghori, a Turkic ruler, conquered Ghazni from the Ghaznavids and became its governor in 1173. He for the first time named Sindh Tambade Gatar roughly translated as the red passage. He marched eastwards into the remaining Ghaznavid territory and Gujarat in the 1180s, but was rebuffed by Gujarat's Hindu Solanki rulers. In 1186–87, he conquered Lahore, bringing the last of Ghaznevid territory under his control and ending the Ghaznavid empire. Muhammad Ghori's successors established the Delhi Sultanate. The Turkic origin Mamluk Dynasty, (mamluk means "owned" and referred to the Turkic youths bought and trained as soldiers who became rulers throughout the Islamic world), seized the throne of the Sultanate in 1211. Several Central Asian Turkic dynasties ruled their empires from Delhi: the Mamluk (1211–90), the Khalji (1290–1320), the Tughlaq (1320–1413), the Sayyid (1414–51) and the Lodhi (1451–1526). Although some kingdoms remained independent of Delhi – in Gujarat, Malwa (central India), Bengal and Deccan – almost all of the Indus plain came under the rule of these large sultanates.

The sultans (emperors) of Delhi enjoyed cordial relations with rulers in the Near East but owed them no allegiance. While the sultans ruled from urban centers, their military camps and trading posts provided the nuclei for many towns that sprang up in the countryside. Close interaction with local populations led to cultural exchange and the resulting "Indo-Islamic" fusion has left a lasting imprint and legacy in South Asian architecture, music, literature, life style and religious customs. In addition, the language of Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Delhi Sultanate period, as a result of the mingling of speakers of native Prakrits, Persian, Turkish and Arabic languages.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of the Sultanate was its temporary success in insulating South Asia from the Mongol invasion from Central Asia in the 13th century; nonetheless the sultans eventually lost Afghanistan and western Pakistan to the Mongols (see the Ilkhanate Dynasty). The Sultanate declined after the invasion of Emperor Timur, who founded the Timurid Dynasty, and was eventually conquered in 1526 by the Mughal king Babar.

Guru Nanak (1469–1539), was born in the village of Rāi Bhōi dī Talwandī, now called Nankana, near Sial in modern-day Pakistan into a Hindu Khatri family. He was an influential religious and social reformer of north India and the saintly founder of a modern monothiestic order and first of the ten divine Gurus of Sikh Religion. At the age of 70, he had a miraculous death in Cartarpur, Punjab of modern-day Pakistan. Sikhism was created and would continue to grow; its followers, the Sikhs, would politicalise and militarise to play a historic role later.

Mughal Empire

In 1526, Babur, a Timurid descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan from Fergana Valley (modern day Uzbekistan), swept across the Khyber Pass and founded the Mughal Empire, covering modern day Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.[46] The Mughals were descended from Central Asian Turks (with significant Mongol admixture). However, his son Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior Sher Shah Suri who was from Bihar state of India, in the year 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to Kabul. After Sher Shah died, his son Islam Shah Suri became the ruler, on whose death his prime minister, Hemu ascended the throne and ruled North India from Delhi for one month. He was defeated by Emperor Akbar's forces in the Second Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556.

Akbar the Great, was both a capable ruler and an early proponent of religious and ethnic tolerance and favored an early form of multiculturalism. He declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism and rolled back the jizya tax imposed upon non-Islamic mainly Hindu people. The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600. The Mughal emperors married local royalty and allied themselves with local maharajas. For a short time in the late 16th century, Lahore was the capital of the empire. The architectural legacy of the Mughals in Lahore includes the Shalimar Gardens built by the fifth Emperor Shahjahan, and the Badshahi Mosque built by the sixth Emperor, Aurangzeb, who is regarded as the last Great Mughal Emperor as he expanded the domain to its zenith of Template:Convert/e9. After his demise, different regions of modern Pakistan began asserting independence. The empire went into a slow decline after 1707 and its last sovereign, ruling around Delhi region.

Post Mughal era

In 1739, Nader Shah, the Turkic emperor of Afsharid dynasty in Persia, invaded South Asia, defeated the Mughal Emperor Mohammed Shah at the huge Battle of Karnal, and occupied most of Balochistan and the Indus plain.[47] After Nadir Shah's death, the Durrani kingdom was established in 1747 by one of his Afghan generals, Ahmad Shah Abdali, and included Balochistan, Peshawar, Daman, Multan, Sind and Punjab. In the south, a succession of autonomous dynasties (the Daudpotas, Kalhoras and Talpurs) had asserted the independence of Sind, from the end of Aurangzeb's reign. Most of Balochistan came under the influence of the Khan of Kalat, apart from some coastal areas such as Gwadar, which were controlled by mutually competing and armed Portuguese, French and Dutch trading companies.

In 1758 the Maratha Empire's general Raghunathrao marched onwards, attacked and conquered Lahore and Attock and drove out Timur Shah Durrani, the son and viceroy of Ahmad Shah Abdali. Lahore, Multan, Kashmir and other subahs on the south eastern side of Attock were under the Maratha rule for the most part. In Punjab and Kashmir, the Marathas were now major players.[48][49] In 1761, following the victory at the Third battle of Panipat between the Durrani and the Maratha Empire, Ahmad Shah Abdali captured remnants of the Maratha Empire in Punjab and Kashmir regions and had consolidated control over them.[50]

Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire (1799–1849) was formed on the foundations of the Punjabi Army by Maharaja Ranjit Singh who was proclaimed "Sarkar-i-Khalsa", and was referred to as the "Maharaja of Lahore".[51] It consisted of a collection of autonomous Punjabi Misls, which were governed by Misldars,[52] mainly in the Punjab region. The empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, to Multan in the south and Kapurthala in the east. The main geographical footprint of the empire was the Punjab region. The formation of the empire was a watershed and represented the resurgence of the local culture and power which had been subdued for hundreds of years by Afghan and Mughal rule.

The foundations of the Sikh Empire, during the time of the Punjabi Army, could be defined as early as 1707, starting from the death of Aurangzeb. The fall of the Mughal Empire provided opportunities for the Punjabi army to lead expeditions against the Mughals and Pashtuns. This led to a growth of the army, which was split into different Punjabi armies and then semi-independent "misls". Each of these component armies were known as a misl, each controlling different areas and cities. However, in the period from 1762–1799, Sikh rulers of their misls appeared to be coming into their own. The formal start of the Sikh Empire began with the disbandment of the Punjab Army by the time of coronation of Ranjit Singh in 1801, creating a unified political state. All the misl leaders who were affiliated with the Army were nobility with usually long and prestigious family histories in Punjab's history.[52][53]

British colony

The entire territory of modern Pakistan was occupied by the British East India Company, then the British Empire, through a series of wars, the main ones being the Battle of Miani (1843) in Sindh, the gruelling Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845–1849) and the First, Second, and Third Anglo-Afghan Wars (1839–1919), to remain a part of British Indian Empire until the freedom in 1947. The physical presence of the British was not very significant; they employed "Divide and Rule" political strategy to rule. In his historical survey Constantine's Sword, James P. Carroll writes: "Certainly that was the story of the British Empire's success, and its legacy of nurtured local hatreds can be seen wherever the Union Flag flew." .[54] The administrative units of British India under the tenancy or the sovereignty of either the East India Company or the British Crown lasted between 1612 and 1947.

Freedom Movement

Early nationalism period

In 1877, Syed Ameer Ali had formed the Central National Muhammadan Association to work towards the political advancement of the Muslims, who had suffered grievously in 1857, in the aftermath of the failed Sepoy Mutiny against the British East India Company; the British were seen as foreign invaders. But the organization declined towards the end of the 19th century.

In 1885, the Indian National Congress was founded as a forum, which later became a party, to promote a nationalist cause.[55] Although the Congress attempted to include the Muslim community in the struggle for independence from the British rule - and some Muslims were very active in the Congress - the majority of Muslim leaders did not trust the party, viewing it as a "Hindu-dominated" organization.[citation needed] Some Muslims felt that an independent united India would inevitably be "ruled by Hindus",[citation needed] and that there was a need to address the issue of the Muslim identity within India.[citation needed] A turning point in national amity came in 1900, when the British administration in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh acceded to Hindu demands and made Hindi, written in the Devanagari script, the official language. The proslytisation conducted in the region by the activists of a new Hindu reformist movement also stirred Muslim's concerns about their faith. Eventually, the Muslims feared that the Hindu majority would seek to suppress Muslim culture and religion in the region of an independent Hindustan.

The Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League was founded on 30 December 1906, in the aftermath of partition of Bengal, on the sidelines of the annual All India Muhammadan Educational Conference in Shahbagh, Dhaka.[56] The meeting was attended by three thousand delegates and presided over by Nawab Viqar-ul-Mulk. It addressed the issue of safeguarding interests of Muslims and finalised a programme. A resolution, moved by Nawab Salimullah and seconded by Hakim Ajmal Khan. Nawab Viqar-ul-Milk, declared:

The Musalmans are only a fifth in number as compared with the total population of the country, and it is manifest that if at any remote period the British government ceases to exist in India, then the rule of India would pass into the hands of that community which is nearly four times as large as ourselves ...our life, our property, our honour, and our faith will all be in great danger, when even now that a powerful British administration is protecting its subjects, we the Musalmans have to face most serious difficulties in safe-guarding our interests from the grasping hands of our neighbors.[57]

The constitution and principles of the League were contained in the Green Book, written by Maulana Mohammad Ali. Its goals at this stage did not include establishing an independent Muslim state, but rather concentrated on protecting Muslim liberties and rights, promoting understanding between the Muslim community and other Indians, educating the Muslim and Indian community at large on the actions of the government, and discouraging violence. However, several factors over the next thirty years, including sectarian violence, led to a re-evaluation of the League's aims.[58][59] Among those Muslims in the Congress who did not initially join the League was Muhammed Ali Jinnah, a prominent statesman and barrister in Bombay. This was because the first article of the League's platform was "To promote among the Mussalmans (Muslims) of India, feelings of loyalty to the British Government".

In 1907, a vocal group of Hindu hard-liners within the Indian National Congress movement separated from it and started to pursue a pro-Hindu movement openly. This group was spearheaded by the famous trio of Lal-Bal-Pal - Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal of Punjab, Bombay and Bengal provinces respectively. Their influence spread rapidly among other like minded Hindus - they called it Hindu nationalism - and it became a cause of serious concern for Muslims. However, Jinnah did not join the League until 1913, when the party changed its platform to one of Indian independence, as a reaction against the British decision to reverse the 1905 Partition of Bengal, which the League regarded it as a betrayal of the Bengali Muslims.[60] After vociferous protests of the Hindu population and violence engineered by secret groups, such as Anushilan Samiti and its offshoot Jugantar of Aurobindo and his brother etc., the British had decided to reunite Bengal again. Till this stage, Jinnah believed in Mutual co-operation to achieve an independent, united 'India', although he argued that Muslims should be guaranteed one-third of the seats in any Indian Parliament.

The League gradually became the leading representative body of Indian Muslims. Jinnah became its president in 1916, and negotiated the Lucknow Pact with the Congress leader, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, by which Congress conceded the principle of separate electorates and weighted representation for the Muslim community.[61] However, Jinnah broke with the Congress in 1920 when the Congress leader, Mohandas Gandhi, launched a law violating Non-Cooperation Movement against the British, which a temperamentally law abiding barrister Jinnah disapproved of. Jinnah also became convinced that the Congress would renounce its support for separate electorates for Muslims, which indeed it did in 1928. In 1927, the British proposed a constitution for India as recommended by the Simon Commission, but they failed to reconcile all parties. The British then turned the matter over to the League and the Congress, and in 1928 an All-Parties Congress was convened in Delhi. The attempt failed, but two more conferences were held, and at the Bombay conference in May, it was agreed that a small committee should work on the constitution. The prominent Congress leader Motilal Nehru headed the committee, which included two Muslims, Syed Ali Imam and Shoaib Quereshi; Motilal's son, Pt Jawaharlal Nehru, was its secretary. The League, however, rejected the committee's report, the so called Nehru Report, arguing that its proposals gave too little representation (one quarter) to Muslims – the League had demanded at least one-third representation in the legislature. Jinnah announced a "parting of the ways" after reading the report, and relations between the Congress and the League began to sour.

Muslim homeland - "Now or Never"

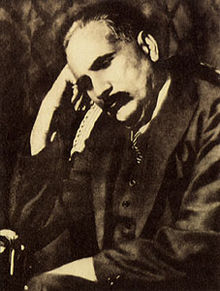

The election of Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government in 1929 in Britain, already weakened by World War I, fuelled new hopes for progress towards self-government in British-India. Gandhi travelled to London, claiming to represent all Indians and criticising the League as sectarian and divisive. Round-table talks were held, but these achieved little, since Gandhi and the League were unable to reach a compromise. The fall of the Labour government in 1931 ended this period of optimism. By 1930 Jinnah had despaired of Indian politics and particularly of getting mainstream parties like the Congress to be sensitive to minority priorities. A fresh call for a separate state was then made by the famous writer, poet and philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal, who in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that he felt that a separate Muslim state was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated South Asia.[6][62] The name was coined by Cambridge student and Muslim nationalist Choudhary Rahmat Ali,[63] and was published on 28 January 1933 in the pamphlet Now or Never.[64] After naming the country, he noticed that there is an acronym formed from the names of the "homelands" of Muslims in northwest India — "P" for Punjab, "A" for the Afghan areas of the region, "K" for Kashmir, "S" for Sindh and "tan" for Balochistan, thus forming "Pakstan".[citation needed] An "i" was later added to the English rendition of the name to ease pronunciation, producing "Pakistan". In Urdu and Persian the name encapsulates the concept of pak ("pure") and stan ("land") and hence a "Pure Land".[65] In the 1935, the British administration proposed to hand over substantial power to elected Indian provincial legislatures, with elections to be held in 1937. After the elections the League took office in Bengal and Punjab, but the Congress won office in most of the other provinces, and refused to devolve power with the League in provinces with large Muslim minorities citing technical difficulties.

Meanwhile, Muslim ideologues for independence also felt vindicated by the presidential address of V.D. Savarkar at the 19th session of the famous Hindu nationalist party Hindu Mahasabha in 1937. In it, this legendary revolutionary - popularly called Veer Savarkar and known as the iconic father of the Hindu fundamentalist ideology - propounded the seminal ideas of his Two Nation Theory or ethnic exclusivism, which influenced Jinnah profoundly.

In 1940, Jinnah called a general session of the Muslim League in Lahore to discuss the situation that had arisen due to the outbreak of the Second World War and the Government of India joining the war without consulting Indian leaders. The meeting was also aimed at analyzing the reasons that led to the defeat of the Muslim League in the general election of 1937 in the Muslim majority provinces. In his speech, Jinnah criticized the Indian National Congress and the nationalists, and espoused the Two-Nation Theory and the reasons for the demand for separate homelands.[66] Sikandar Hayat Khan, the Chief Minister of Punjab, drafted the original resolution, but disavowed the final version,[67] that had emerged after protracted redrafting by the Subject Committee of the Muslim League. The final text unambiguously rejected the concept of a United India because of increasing inter-religious violence[68] and recommended the creation of independent states.[69] The resolution was moved in the general session by Shere-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Huq, the Chief Minister of Bengal, supported by Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman and other leaders and was adopted on 23 March 1940.[7] The Resolution read as follows:

No constitutional plan would be workable or acceptable to the Muslims unless geographical contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be so constituted with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary. That the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in majority as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.... That adequate, effective and mandatory safeguards shall be specifically provided in the constitution for minorities in the units and in the regions for the protection of their religious, cultural, economic, political, administrative and other rights of the minorities, with their consultation. Arrangements thus should be made for the security of Muslims where they were in a minority.[70]

In 1941 it became part of the Muslim League's constitution.[71] However, in early 1941, Sikandar explained to the Punjab Assembly that he did not support the final version of the resolution.[72] The sudden death of Sikandar in 1942 paved the way over the next few years for Jinnah to emerge as the recognised leader of the Muslims of South Asia.[60] In 1943, the Sind Assembly passed a resolution demanding the establishment of a homeland.[73] Talks between Jinnah and Gandhi in 1944 in Bombay failed to achieve agreement and there were no more attempts to reach a single-state solution.

World War II had broken the back of both Britain and France and disintegration of their colonial empires was expected soon.[citation needed] Rebellions and protest against the British had increased. With the election of another sympathetic Labour government in Britain in 1945, Indians were seeing independence within reach. But, Gandhi and Nehru were not receptive to Jinnah's proposal and were also adamantly opposed to dividing India, since they knew that the Hindus, who saw India as one indivisible entity, would never agree to such a thing.[60] In the Constituent Assembly elections of 1946, the League won 425 out of 496 seats reserved for Muslims (polling 89.2% of total votes) on a policy of creating an independent state of Pakistan, and with an implied threat of secession if this was not granted.[60] By 1946 the British had neither the will, nor the financial resources or military power, to hold India any longer. Political deadlock ensued in the Constituent Assembly, and the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, sent a cabinet mission to India to mediate the situation. When the talks broke down, Attlee appointed Louis Mountbatten as India's last viceroy, to negotiate the independence of Pakistan and India and immediate British withdrawal. Mountbatten, of imperial blood and a world war admiral, handled the problem as a campaign. Ignorant of the complex ground realities in British India,[citation needed] he brought forward the date of transfer of power and told Gandhi and Nehru that if they did not accept division there would be civil war in his opinion[60] and he would rather consider handing over power to individual provinces and the rulers of princely states. This forced the hands of Congress leaders and the "Independence of India Act 1947" provided for the two dominions of Pakistan and India to become independent on the 14 and 15 August 1947 respectively. This result was despite the calls for a third Osmanistan in the early 1940s.

Independence of Pakistan

On the 14th and 15 August 1947, British India gave way to two new independent states, the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India, both dominions which joined the British Commonwealth. However, the decision to divide Punjab and Bengal, two of the biggest provinces, between India and Pakistan had disastrous consequences. This division created inter-religious violence of such magnitude that exchange of population along religious lines became a necessity in these provinces. More than two million people migrated across the new borders and more than one hundred thousand died in the spate of communal violence, that spread even beyond these provinces. The independence also resulted in tensions over Kashmir leading to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, which culminated in an armistice, brokered by the United Nations, and a hitherto unresolved Kashmir dispute. The post-independence political history of Pakistan has been characterised by several periods of authoritarian military rule and continuing territorial disputes with India over the status of Kashmir.

Modern day Pakistan

First democratic era (1947–1958)

See also: Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, 1958 Pakistani coup d'état, Assassination of liaqat ali khan, Bengali Language Movement, and 1953 Lahore riotsBetween 1947 and 1971, Pakistan consisted of two geographically separate regions, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. Within one year of democratic rule, differences between the two wings of Pakistan surfaced: When Jinnah declared in 1948 that Urdu would be the only state language of Pakistan, it sparked protests in East Bengal (later East Pakistan), where Bengali was spoken by most of the population. The Bengali Language Movement reached its peak on 21 February 1952, when the police and soldiers opened fire on students near the Dhaka Medical College protesting for Bengali to receive equal status with Urdu. Several protesters were killed, and the movement gained further support throughout East Pakistan. Later, the Government agreed to provide equal status to Bengali as a state language of Pakistan, a right later codified in the 1956 constitution.

In 1953 at the instigation of religious parties, anti-Ahmadiyya riots erupted, killing scores of non-Ahmadis and destroying their properties.[74] The riots were investigated by a two-member court of inquiry in 1954,[75] which was criticised by the Jamaat-e-Islami, one of the parties accused of inciting the riots.[76] This event led to the first instance of martial law in the country and began the inroad of military intervention in the politics and civilian affairs of the country, something that remains to this day.[77]

First military era (1958–1971)

Main articles: Ayub Khan (Field Marshal), Yahya Khan, Bangladesh Liberation War, Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, Cold war, East Pakistan, and West PakistanThe Dominion was dissolved on 23 March 1956 and replaced by the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, with the last Governor-General, Iskandar Mirza, as the first president.[78] Just two years later the military took control of the nation.[79] Field Marshal Ayub Khan became president and began a new system of government called Basic Democracy with a new constitution,[80] by which an electoral college of 80,000 would select the President. Ayub Khan almost lost the controversial 1965 presidential elections to Fatima Jinnah.[81] During Ayub's rule, relations with the United States and the West grew stronger. Pakistan joined two formal military alliances — the Baghdad Pact (later known as the Central Treaty Organization or CENTO) which included Iran, Iraq, and Turkey to defend the Middle East and Persian Gulf against the Soviet Union;[82] and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) which covered South-East Asia.[83] However, the United States dismayed Pakistan by adopting a policy of denying military aid to both India and Pakistan during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 over Kashmir and the Rann of Kutch.[84] A positive gain of the treaties was the re-srengthening of Pakistan's close historical bonds with its western neighbours.

During the 1960s, amidst the allegations that economic development and hiring for government jobs favoured West Pakistan, there was a rise in Bengali nationalism and an independence movement in East Pakistan began to gather ground. After a nationwide uprising in 1969, General Ayub Khan stepped down from office, handing power to General Yahya Khan, who promised to hold general elections at the end of 1970. On the eve of the elections, a cyclone struck East Pakistan killing approximately 500,000 people. Despite the tragedy and the additional difficulty experienced by affected citizens in reaching the voting sites, the elections were held and the results showed a clear division between East and West Pakistan. The Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a majority with 167 of the 169 East Pakistani seats, but with no seats in West Pakistan, where the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, won 85 seats, none in East Pakistan. However, Yahya Khan and Bhutto refused to hand over power to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Meanwhile, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman initiated a civil disobedience movement, which was strongly supported by the general population of East Pakistan, including most government workers. A round-table conference between Yahya, Bhutto, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was convened in Dhaka, which, however, ended without a solution. Soon thereafter, the West Pakistani Army commenced Operation Searchlight, an organized crackdown on the East Pakistani army, police, politicians, civilians, and students in Dhaka. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and many other Awami League leaders were arrested, while others fled to neighbouring India. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was taken to West Pakistan. The crackdown widened and escalated into a guerrilla warfare between the Pakistani Army and the Mukti Bahini (Bengali "freedom fighters").[8] In March 1971, India's Prime Minister announced support for the Liberation War, providing military assistance. Ultimately 300,000 to 3,000,000 died in the war[85] and millions Hindus and Bengali fled to India.[86] On 27 March 1971, Major Ziaur Rahman, a Bengali war-veteran of the East Bengal Regiment of the Pakistan Army, declared the independence of East Pakistan as the new nation of Bangladesh on behalf of Mujib.

Following a period of covert and overt intervention by Indian forces in the conflict, open hostilities broke out between India and Pakistan on 3 December 1971. In Bangladesh, the Pakistani Army led by General A. A. K. Niazi, had already been weakened and exhausted by the Mukti Bahini's guerrilla warfare. Outflanked and overwhelmed, the Pakistani army in the eastern theatre surrendered on 16 December 1971, with nearly 90,000 soldiers taken as prisoners of war. The result was the defacto emergence of the new nation of Bangladesh,[9] thus ending 24 years of turbulent union of the two wings. The figures of the Bengali civilian death toll from the entire civil war vary greatly, depending on the sources. Although the killing of Bengalis was unsupported by the people of West Pakistan, it continued for 9 months. Pakistan's official report, by the Hamood-ur-Rahman Commission, placed the figure at only 26,000, while estimates range up to 3 million.

Discredited by the defeat, General Yahya Khan resigned and Bhutto was inaugurated as president and chief martial law administrator on 20 December 1971.

Second democratic era (1971–1977)

Main articles: Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, 1970s Operation in Balochistan, Project-706, Pakistan and its Nuclear Detterent Program, Hamoodur Rahman Commission, Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, Pakistan, and Pakistan Atomic Energy CommissionCivilian rule returned after the war, when General Yahya Khan handed over power to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. In 1972, Pakistan's ISI and MI learned that India was close to developing a nuclear weapon under its nuclear programme. In response, Bhutto called secret meeting, which came to known as Multan meeting, and rallied academic scientists to build the atomic bomb for national survival. Bhutto was the main architect of the programme as he planned the entire programme loosely based on Manhattan Project of 1940s. This programme was headed by large groups of prominent academic scientists and engineers, directly reported and headed by nuclear scientist Abdus Salam — who later won the Nobel Prize for Physics — to develop nuclear devices. In 1973, Parliament approved a new constitution, and Pakistan, for the first time, was declared Parliamentary democracy. In 1974, Pakistan was alarmed by the Indian nuclear test, and Bhutto promised to his nation that Pakistan would also have a nuclear device "even if we have to eat grass and leaves."

During Bhutto's rule, a serious rebellion also took place in Balochistan province and led to harsh suppression of Baloch rebels with the Shah of Iran purportedly assisting with air support in order to prevent the conflict from spilling over into Iranian Balochistan. The conflict ended later after an amnesty and subsequent stabilization by the provincial military ruler Rahimuddin Khan. In 1974, Bhutto succumbed to increasing pressure from religious parties and helped Parliament to declare the Ahmadiyya adherents as non-Muslims. Elections were held in 1977, with the Peoples Party won but this was challenged by the opposition, which accused Bhutto of rigging the election process. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq took power in a bloodless coup and Bhutto was later executed, after being convicted of authorizing the murder of a political opponent, in a controversial 4-3 split decision by the Supreme Court.

Second military era (1977–1988)

Main articles: Operation Fair Play, Baghdad Pact, Zia-ul-Haq's Islamization, Baloch Insurgency and Rahimuddin's Stabilization, Siachen conflict, Operation Brasstacks, Soviet war in Afghanistan, Operation Cyclone, Death of Zia-ul-Haq, and Insurgency in Jammu and KashmirPakistan had been a US ally for much of the Cold War, from the 1950s and as a member of CENTO and SEATO. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan renewed and deepened the US-Pakistan alliance. The Reagan administration in the United States helped supply and finance an anti-Soviet insurgency in Afghanistan, using Pakistan as a conduit. In retaliation, the Afghan secret police, KHAD, carried out a large number of terrorist operations against Pakistan, which also suffered from an influx of illegal weapons and drugs from Afghanistan. In the 1980s, as the front-line state in the anti-Soviet struggle, Pakistan received substantial aid from the United States as it took in millions of Afghan (mostly Pashtun) refugees fleeing the Soviet occupation. The influx of so many refugees - the largest refugee population in the world[87] - had a heavy impact on Pakistan and its effects continue to this day. Zia's martial-law administration gradually reversed the socialist policies of the previous government, and also introduced strict Islamic law in 1978, often cited as the contributing factor in the present climate of sectarianism and religious fundamentalism in Pakistan. Ordinance XX was introduced to limit the idolatrous Ahmadis from misrepresenting themselves as Muslims. Further, in his time, independence uprisings in Balochistan were put down successfully by the provincial governor, General Rahimuddin Khan.

Zia lifted martial law in 1985, holding non-partisan elections and handpicking Muhammad Khan Junejo to be the new Prime Minister, who readily extended Zia's term as Chief of Army Staff until 1990. Junejo however gradually fell out with Zia as his administrative independence grew; for example, Junejo signed the Geneva Accord, which Zia greatly frowned upon. After a large-scale blast at a munitions dump in Ojhri, Junejo vowed to bring to justice those responsible for the significant damage caused, implicating several senior generals. Zia dismissed the Junejo government on several charges in May 1988 and called for elections in November 1988. However, Zia died in a plane crash on 17 August 1988.

Third democratic era (1988–1999)

Main articles: Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, Indo-Pakistani War of 1999, Chagai-I, Chagai-II, Atlantique Incident, and Civil war in Afghanistan (1996–2001)From 1988 to 1999, Pakistan through constitutional amendments was reverted back to Parliamentary democracy system, and Pakistan was ruled by elected civilian governments, alternately headed by Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif, who were each elected twice and removed from office on charges of corruption. During the late 1990s, Pakistan was one of three countries which recognized the Taliban government and Mullah Mohammed Omar as the legitimate ruler of Afghanistan.[88] Allegations have been made of Pakistan and other countries providing economic and military aid to the group from 1994 as a part of supporting the anti-Soviet alliance. It is alleged that some post-invasion Taliban fighters were recruits drawn from Pakistan's madrassahs. Economic growth declined towards the end of this period, hurt by the Asian financial crisis, and economic sanctions imposed on Pakistan after its first tests of nuclear devices in 1998. The Pakistani testing came shortly after India tested nuclear devices and increased fears of a nuclear arms race in South Asia. The next year, Kargil attack by Pakistan backed Kashmiri militants threatened to escalate to a full-scale war.[10]

In the 1997 election that returned Nawaz Sharif as Prime Minister, his party received a heavy majority of the vote, obtaining enough seats in parliament to change the constitution, which Sharif amended to eliminate the formal checks and balances that restrained the Prime Minister's power. Institutional challenges to his authority led by the civilian President Farooq Leghari, military chief Jehangir Karamat and Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah were put down and all three were forced to resign - Shah doing so after the Supreme Court was stormed by Sharif partisans.[89]

Third military era (1999–2007)

Main articles: 1999 Pakistani coup d'état, Pervez Musharraf, 2001–2002 India-Pakistan standoff, War in North-West Pakistan, Assassination of Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan's role in the War on Terror, War on Terror, and Lawyers' MovementOn 12 October 1999, Sharif attempted to dismiss army chief Pervez Musharraf and install Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) director Ziauddin Butt in his place, but senior generals refused to accept the decision.[90] Musharraf, who was out of the country, boarded a commercial airliner to return to Pakistan. Sharif ordered the Jinnah International Airport to prevent the landing of the airliner, which then circled the skies over Karachi. In a coup, the generals ousted Sharif's administration and took over the airport.[91] The plane landed with only a few minutes of fuel to spare, and General Musharraf assumed control of the government. He arrested Sharif and those members of his cabinet who took part in this conspiracy. American President Bill Clinton had felt that his pressure to force Sharif to withdraw Pakistani forces from Kargil, in Indian-controlled Kashmir, was one of the main reasons for disagreements between Sharif and the Pakistani army. Clinton and King Fahd then pressured Musharraf to spare Sharif and, instead, exile him to Saudi Arabia, guaranteeing that he would not be involved in politics for ten years. Sharif lived in Saudi Arabia for more than six years before moving to London in 2005.

On 12 May 2000 the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered the Government to hold general elections by 12 October 2002. In an attempt to legitimize his presidency[92] and assure its continuance after the impending elections, Musharraf held a controversial national referendum on 30 April 2002,[93] which extended his presidential term to a period ending five years after the October elections.[94] Musharraf strengthened his position by issuing a Legal Framework Order in August 2001 which established the constitutional basis for his continuance in office.[95] The general elections were held in October 2002 and the centrist, pro-Musharraf Pakistan Muslim League (Q) (PML-Q) won a majority of the seats in Parliament. However, parties opposed to the Legal Framework Order effectively paralysed the National Assembly for over a year. The deadlock ended in December 2003, when Musharraf and some of his parliamentary opponents agreed upon a compromise, and pro-Musharraf legislators were able to muster the two-thirds majority required to pass the Seventeenth Amendment, which retroactively legitimized Musharraf's 1999 coup and many of his subsequent decrees. In a vote of confidence on 1 January 2004, Musharraf won 658 out of 1,170 votes in the Electoral College of Pakistan, and according to Article 41(8) of the Constitution of Pakistan, was elected to the office of President.[96]

While economic reforms undertaken during his regime yielded positive results, proposed social reforms were met with resistance. Musharraf faced opposition from religious groups who were angered by his post-9/11 political alliance with the United States and his military support to the American led 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. He survived several assassination attempts by groups believed to be part of Al-Qaeda, including at least two instances where they had inside information from a member of his military security.[citation needed]

Pakistan continues to be involved in a dispute over Kashmir, with allegations of support of separatist Kashmiri militants being leveled against Pakistan by India - which treats them as terror-groups - while Pakistan charges that the Indian government abuses human rights in its excessive use of military force in the disputed region. What makes this dispute a source of special concern for the world community is that both India and Pakistan possess nuclear weapons. It had led to a nuclear standoff in 2002, when Kashmiri-militants, allegedly backed by the ISI, attacked the Indian parliament. In reaction to this, serious diplomatic tensions developed and India and Pakistan deployed 500,000 and 120,000 troops to the border respectively.[97] While the Indo-Pakistani peace process has since made progress, it is sometimes stalled by infrequent insurgent activity in India, such as the 26/11 Mumbai attacks. Pakistan also has been accused of contributing to nuclear proliferation; its leading nuclear scientist, Abdul Qadeer Khan, admitted to selling nuclear secrets, though he denied government knowledge of his activities.

After the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, the Pakistani government, as an ally, sent thousands of troops into the mountainous region of Waziristan in 2002, in search of bin-Laden (the master-mind behind the 11 September attacks in 2001) and other heavily armed al-Qaeda members, who had taken refuge there. In March 2004, heavy fighting broke out at Azam Warsak (near the South Waziristan town of Wana), between Pakistani troops and these militants (estimated to be 400 in number), who were entrenched in several fortified settlements. It was speculated that bin Laden's deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri was among those trapped by the Pakistani Army. On 5 September 2006 a truce was signed with the militants and their local rebel supporters, (who called themselves the Islamic Emirate of Waziristan), in which the rebels were to cease supporting the militants in cross-border attacks on Afghanistan in return for a ceasefire and general amnesty and a hand-over of border-patrolling and check-point responsibilities, till then handled by the Pakistan Army.

Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif attempted to return from exile on 10 September 2007 but was arrested on corruption charges after landing at Islamabad International Airport. Sharif was then put on a plane bound for Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, whilst outside the airport there were violent confrontations between Sharif's supporters and the police.[98] This did not deter another former prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, from returning on 18 October 2007 after an eight year exile in Dubai and London, to prepare for the parliamentary elections to be held in 2008.[99][100] However, on the same day, two suicide bombers attempted to kill Bhutto as she travelled towards a rally in Karachi. Bhutto escaped unharmed but there were 136 casualties and at least 450 people were injured.[101]

On 3 November 2007, General Musharraf proclaimed a state of emergency and sacked the Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Choudhry along with other 14 judges of the Supreme Court.[102][103] Lawyers launched a protest against this action but they were arrested. All private media channels were banned including foreign channels. Musharraf declared that the state of emergency would end on 16 December 2007.[104] On 28 November 2007, General Musharraf retired from the Army and the following day was sworn in for a second presidential term.[105][106]

On 25 November 2007, Nawaz Sharif made a second attempt to return from exile, this time accompanied by his brother, the former Punjab chief minister, Shahbaz Sharif. Hundreds of their supporters, including a few leaders of the party were detained before the pair arrived at Lahore International Airport.[107][108] The following day, Nawaz Sharif filed his nomination papers for two seats in the forthcoming elections whilst Benazir Bhutto filed for three seats including one of the reserved seats for women.[109]

On 27 December 2007, Benazir Bhutto was leaving an election rally in Rawalpindi when she was assassinated by a gunman who shot her in the neck and set off a bomb,[110][111] killing 20 other people and injuring several more.[112] The exact sequence of the events and cause of death became points of political debate and controversy, because, although early reports indicated that Bhutto was hit by shrapnel or the gunshots,[113] the Pakistani Interior Ministry stated that she died from a skull fracture sustained when the explosion threw Bhutto against the sunroof of her vehicle.[114] Bhutto's aides rejected this claim and insisted that she suffered two gunshots prior to the bomb detonation.[115] The Interior Ministry subsequently backtracked from its previous claim.[116] However, a subsequent investigation, aided by the Scotland Yard of U.K., supported the "hitting the sun-roof"" as the cause of her death. The Election Commission, after a meeting in Islamabad, announced that, due to the assassination of Benazir Bhutto,[117] the elections, which had been scheduled for 8 January 2008, would take place on 18 February.[118]

A general election was held in Pakistan, according to the revised schedule, on 18 February 2008,).[119][120] Pakistan's two big and main opposition parties, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML (N)), won majority of seats in the election and formed a government. Although, the Pakistan Muslim League (Q) (PML (Q)) actually was second in the popular vote, the PPP and PML (N) have formed the new coalition-government.

On 7 August, a deadlock between ruling parties ended when the coalition government of Pakistan decided to move for the impeachment of the President before heading for the restoration of the deposed judiciary. Moreover, they decided that Pervez Musharraf should face charges of weakening Pakistan's federal structure, violating its constitution and creating economic impasse.[121]

After that, President Pervez Musharraf began consultations with his allies, and with his legal team, on the implications of the impeachment; he said that he was ready to reply to the charges levied upon him and seek the vote of confidence from the senate and the parliament, as required by the coalition parties. However, on 18 August 2008, President Pervez Musharraf announced in a televised address to the nation that he had decided to resign after nine years in office.[122]

Fourth democratic era (2008–present)

Main articles: Pakistani general election, 2008, Operation Black Thunderstorm, Operation Rah-e-Haq, Operation Rah-e-Nijat, and Suspension of Iftikhar Muhammad ChaudhryIn the presidential election that followed President Pervez Musharraf's resignation, Asif Ali Zardari of the PPP was elected President of Pakistan. Zardari's government is facing the formidable challenges of a war next door, a never-ending territorial dispute, and ever-present internal political bickering.

Pakistan, under Zardari and Gillani's administration, is heading back toward a major transition from the existing semi-presidential system to parliamentary democracy rule: The Parliament of Pakistan has passed the 18th amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan —- a bill which, inter alia, is to remove the power of the President of Pakistan to dissolve the parliament unilaterally. This constitutional amendment is considered a major step toward the parliamentary democracy in the country; it reverses many amendments to the constitution carried out since 1973, turns the President into a ceremonial head of state and transfers the authoritarian and executive powers to the Prime Minister .[123]

A major event of international importance occurred on the soil of Pakistan on 2 May 2011: The Al-Qaeda supremo Osama bin Laden was claimed to have been assassinated in his elusive secret hideout in Abbottabad, Pakistan by the crack Navy Seal commandos of USA, through a daring air born attack, without the knowledge of Pakistan Government. This secret mission was personally authorised by US-president Barack Obama.

See also

References

- ^ a b Coppa, A.; L. Bondioli, A. Cucina, D. W. Frayer, C. Jarrige, J. F. Jarrige, G. Quivron, M. Rossi, M. Vidale, R. Macchiarelli (6 April 2006). "Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry" (PDF). Nature 440 (7085): 755–756. doi:10.1038/440755a. PMID 16598247. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7085/pdf/440755a.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ Possehl, G. L. (October 1990). "Revolution in the Urban Revolution: The Emergence of Indus Urbanization". Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1): 261–282. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001401. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/toc/anthro/19/1?cookieSet=1. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark; Kimberley Heuston (May 2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517422-9. http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/HistoryWorld/Ancient/Other/~~/dmlldz11c2EmY2k9OTc4MDE5NTE3NDIyOQ==.

- ^ "Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of Pakistan". Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield. http://www.shef.ac.uk/archaeology/research/pakistan. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Murray, Tim (1999). Time and archaeology. London; New York: Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-415-11762-3. http://books.google.com/?id=k3z9iXo_Uq8C&pg=PP3&dq=%22Time+and+Archaeology%22.

- ^ a b "Sir Muhammad Iqbal's 1930 Presidential Address". Speeches, Writings, and Statements of Iqbal. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_iqbal_1930.html. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ a b Qutubuddin Aziz. "Muslim's struggle for independent statehood". Jang Group of Newspapers. http://www.jang.com.pk/thenews/spedition/23march2007/index.html#b. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ a b "The 1971 war". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/south_asia/2002/india_pakistan/timeline/1971.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b "The War for Bangladeshi Independence, 1971". Country Studies. U. S. Library of Congress. http://countrystudies.us/bangladesh/17.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b "India launches Kashmir air attack". BBC News. 26 May 1999. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/352995.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh". Guide to Archaeology

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. 1996. "Mehrgarh." Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- ^ The Centre for Archaeological Research Indus Balochistan, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques — Guimet

- ^ Chandler, Graham. 1999. "Traders of the Plain". Saudi Aramco World.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg; Subhash Kak; David Frawley (1995). In search of the cradle of civilization: new light on ancient India. Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8356-0720-9. http://books.google.com/?id=kbx7q0gxyTcC&printsec=frontcover&dq=In+Search+of+the+Cradle+of+Civilization.

- ^ Stein, Burton (1998). A history of India. Oxford (UK); Malden (Mass.): Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-17899-6.

- ^ "Early Aryan Period." 2007. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 March 2007, from : Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Taxila. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ India: Reemergence of Urbanization. Retrieved on May 12, 2007.

- ^ Valmiki (March 1990). Goldman, Robert P. ed. The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume 1: Balakanda. Ramayana of Valmiki. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 23. ISBN 069101485X.

- ^ a b Krishna Reddy (2003). Indian History. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill. p. A11. ISBN 0070483698.

- ^ M. Witzel, Early Sanskritization. Origins and development of the Kuru State. B. Kölver (ed.), Recht, Staat und Verwaltung im klassischen Indien. The state, the Law, and Administration in Classical India. München : R. Oldenbourg 1997, 27–52 = Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, vol. 1,4, December 1995, [1]

- ^ Herodotus; Aubrey De Sélincourt (trans.) (1954). Herodotus: the Histories. Harmondsworth, Middlesex; Baltimore: Penguin Books. http://www.livius.org/da-dd/darius/darius_i_t08.html. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Plutarchus, Mestrius; Bernadotte Perrin (trans.) (1919). Plutarch's Lives. London: William Heinemann. pp. Ch. LXII. ISBN 978-0-674-99110-1. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plut.+Caes.+62.1. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Plutarchus, Mestrius; Bernadotte Perrin (trans.) (1919). Plutarch's Lives. London: William Heinemann. pp. Ch. LXIII. ISBN 978-0-674-99110-1. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plut.+Caes.+63.1. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Appian of Alexandria; Horace White (trans.) (1899). The Roman History of Appian of Alexandria. Macmillan & Co.. http://www.livius.org/ap-ark/appian/appian_syriaca_11.html. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul: The Name". American International School of Kabul. http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedhistoryfiles.co.uk; see Help:Cite errors/Cite error references no text - ^ McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The shape of ancient thought. New York: Allworth Press. ISBN 978-1-58115-203-6. http://www.google.co.uk/books?id=Vpqr1vNWQhUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+shape+of+ancient+thought%7C+publisher&sig=mLs2tF5QycF9U5uIj9vEsElLbpI. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Strabo; H. L. Jones (ed.) (1924). Geographica. London: William Heinemann. pp. Ch. XI. ISBN 978-0-674-99055-5. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ Davids, T. W. Rhys (trans.) (2000, 1930). The Milinda-questions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24475-6. http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/sbe35/sbe3503.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ "Parthian Pair of Earrings". Marymount School, New York. http://www.marymount.k12.ny.us/marynet/stwbwk05/05vm/earrings/html/emanalysis.html. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ "Gupta Dynasty – MSN Encarta". Gupta Dynasty – MSN Encarta. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761571624/gupta_dynasty.html.

- ^ http://www.fsmitha.com/h1/ch28gup.htm

- ^ http://www.wsu.edu:8001/~dee/ANCINDIA/GUPTA.HTM

- ^ http://www.indianchild.com/gupta_empire.htm

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/249590/Gupta-dynasty

- ^ Mahajan, V.D. (1960) Ancient India, New Delhi: S. Chand, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, p.540

- ^ Gupta dynasty: empire in 4th century – Britannica

- ^ http://www.historybits.com/gupta.htm

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/thestoryofindia/gallery/photos/8.html

- ^ Agarwal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas, Delhi:Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0592-5, pp.264–269

- ^ Thakur Deshraj, Jat Itihas (Hindi), Maharaja Suraj Mal Smarak Shiksha Sansthan, Delhi, 1934, 2nd edition 1992

- ^ A reference to the religion of Emperor Harshavardhana History of India. http://www.culturalindia.net/indian-history/ancient-india/harshavardhan.html.

- ^ Sindh. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 March 2007, from: Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ The Islamic World to 1600: Rise of the Great Islamic Empires (The Mughal Empire)

- ^ Iran in the Age of the Raj

- ^ Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-8178241098.