- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

-

"North West Frontier Province" redirects here. For other uses, see North West Frontier (disambiguation).

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

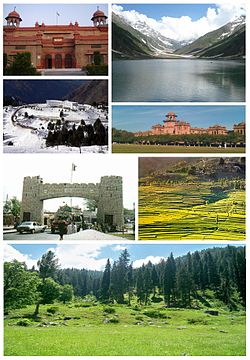

خیبر پښتونخوا— Province — Counter-clockwise from top left: Peshawar Museum, Malam Jabba Ski Resort, Khyber Pass, Swat Valley, Islamia College, Peshawar,

Lake Saiful Muluk, Naran

Flag

LogoCoordinates: 34°00′N 71°19′E / 34.00°N 71.32°ECoordinates: 34°00′N 71°19′E / 34.00°N 71.32°E Country  Pakistan

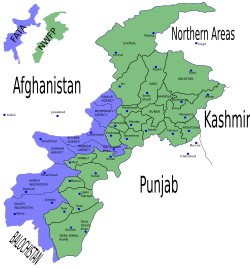

PakistanEstablished July 1, 1970 Capital Peshawar Largest city Peshawar Government - Type Province - Body Provincial Assembly - Governor Syed Masood Kausar[1] - Chief Minister Ameer Haider Khan Hoti - High Court Peshawar High Court Area - Total 74,521 km2 (28,772.7 sq mi) Population (2008 est.) - Total 20,215,000 - Density 271.3/km2 (702.6/sq mi) Time zone PST (UTC+5) Main Language(s) Other: Kohistani, Saraiki, Punjabi Assembly seats 124 Districts 25 Towns Union Councils 986 Website khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Urdu: خیبر پختونخوا [ˈxɛːbər pəxˈt̪uːnxwaː], Pashto: خیبر پښتونخوا [xaibər paʂtunxwɑ], locally Pukhtunkhwa [puxtunxwɑ]), formerly known as the North-West Frontier Province and various other names, is one of the four provinces of Pakistan, located in the north-west of the country. It borders Afghanistan to the north-west, Gilgit-Baltistan to the north-east, Azad Kashmir to the east, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) to the west and south, Balochistan to the south and Punjab and the Islamabad Capital Territory to the south-east.

The main ethnic group in the province is the Pashtuns; other smaller ethnic groups include most notably the Hazarewals and Chitralis. The principal languages are Pashto, locally referred to as Pukhto.

The provincial capital is Peshawar, locally referred to as Pekhawar.

Contents

Geography

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa sits primarily on the Iranian plateau and comprises the junction where the slopes of the Hindu Kush mountains on the Eurasian plate give way to the Indus-watered hills approaching South Asia. This situation has led to seismic activity in the past.[3] The famous Khyber Pass links the province to Afghanistan, while the Kohalla Bridge in Circle Bakote Abbottabad is a major crossing point over the Jhelum River in the east.

The province has an area of 28,773 mi² or (74,521 km²) - comparable in size to New England in North America.[4] The province's main districts are Peshawar, Mardan, Dera Ismail Khan, Lakki Marwat, Kohistan, Kohat, Abbottabad, Haripur and Mansehra, Swat, Bannu and Karak. Peshawar, Mardan, Kohat, Abbottabad and Dera Ismail Khan are the main cities.

The region varies in topography from dry rocky areas in the south to forests and green plains in the north. The climate can be extreme with intensely hot summers to freezing cold winters. Despite these extremes in weather, agriculture remains important and viable in the area.

The hilly terrain of Kalam, Upper Dir, Naran and Kaghan is renowned for its beauty and attracts a great many tourists from neighboring regions and from around the world. Swat is termed 'a piece of Switzerland' as there are many landscape similarities between it and the mountainous terrain of Switzerland.

According to the 1998 census, the population of the province was approximately 17 million.[5] of whom 52% are males and 48% are females. The density of population is 187 per km² and the intercensal change of population is of about 30%. Geographically the province could be divided into two zones: the northern one extending from the ranges of the Hindu Kush to the borders of Peshawar basin, and the southern one extending from Peshawar to the Derajat basin.

The northern zone is cold and snowy in winters with heavy rainfall and pleasant summers with the exception of Peshawar basin, which is hot in summer and cold in winter. It has moderate rainfall. The southern zone is arid with hot summers and relatively cold winters and scanty rainfall.

The major rivers that criss-cross the province are Kabul River, Swat River, Chitral River, Kunar River, Siran River, Panjgora River, Bara River, Kurram River, Dor River, Haroo River, Gomal River and Zhob River.

Its snow-capped peaks and lush green valleys of unusual beauty have enormous potential for tourism .

Climate

The climate of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa varies immensely for a region of its size, encompassing most of the many climate types found in Pakistan. The province stretching southwards from the Baroghil Pass in the Hindu Kush covers almost six degrees of latitude; it is mainly a mountainous region. Dera Ismail Khan is one of the hottest places in the South Asia while in the mountains to the north the weather is temperate in the summer and intensely cold in the winter. The air is generally very dry and consequently the daily and annual range of temperature is quite large.[6]

Rainfall also varies widely. Although large parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are typically dry, the province also contains the wettest parts of Pakistan in its eastern fringe.

Three main climatic regions can be distinguished within Khyber Pakhtunkhwa:

Kundol Lake, Swat valley

Chitral District

Chitral District lies completely sheltered from the monsoon that controls the weather in eastern Pakistan, owing to its relatively westerly location and the shielding effect of the Nanga Parbat massif. In many ways Chitral District has more in common regarding climate with Central Asia than South Asia.[7] The winters are generally cold even in the valleys, and heavy snow during the winter blocks passes and isolates the region from the world. In the valleys, however, summers can be hotter than on the windward side of the mountains due to lower cloud cover: Chitral can reach 40 °C (104 °F) frequently during this period.[8] However, the humidity is extremely low during these hot spells and as a result the summer climate is less torrid than in the rest of the Indian subcontinent.

Most precipitation falls as thunderstorms or snow during winter and spring, so that the climate at the lowest elevations is classed as Mediterranean (Csa), continental Mediterranean (Dsa) or semi-arid (BSk). Summers are extremely dry in the north of Chitral district and receive only a little rain in the south around Drosh. However, at elevations above 5,000 metres (16,400 ft), it is known that as much as a third of the snow which feeds the large Karakoram and Hindukush glaciers comes from the monsoon since these elevations are too high to be shielded from its moisture[7].

Central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Dir Climate chart (explanation) J F M A M J J A S O N D 12111−317712−22541631662388628125432161603119169301884291450257582028314−1Average max. and min. temperatures in °C Precipitation totals in mm Source: World Climate Data[9] Imperial conversion J F M A M J J A S O N D 4.85227754281061376.573463.482542.190616.388666.786643.38457277452.368363.35730Average max. and min. temperatures in °F Precipitation totals in inches On the southern flanks of Nanga Parbat and in Upper and Lower Dir Districts, rainfall is much heavier than further north because moist winds from the Arabian Sea are able to penetrate the region and when they collide with the mountain slopes winter depressions provide heavy precipitation. The monsoon, although short, is generally powerful and as a result the southern slopes of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are the wettest part of Pakistan. Annual rainfall ranges from around 500 millimetres (20 in) in the most sheltered areas to as much as 1,750 millimetres (69 in) in parts of Abbottabad and Mansehra Districts.

This region’s climate is classed at lower elevations as humid subtropical (Cfa in the west; Cwa in the east); whilst at higher elevations with a southerly aspect it becomes classed as humid continental (Dfb). However, accurate data for altitudes above 2,000 metres (6,560 ft) are practically nonexistent either here, in Chitral, or in the south of the province.

The seasonality of rainfall in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shows very marked gradients from east to west. At Dir, March remains the wettest month due to frequent frontal cloud-bands, whereas in Hazara more than half the rainfall comes from the monsoon.[10] This creates a unique situation characterized by a bimodal rainfall regime, which extends into the southern part of the province described below.[10]

Since cold air from the Siberian High loses its chilling capacity upon crossing the vast Karakoram and Himalaya ranges, winters in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are somewhat milder than in Chitral. Snow remains very frequent at high altitudes but rarely lasts long on the ground in the major towns and agricultural valleys. Outside of winter, temperatures in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are not so hot as in Chitral, but significantly higher humidity when the monsoon is active means that heat discomfort can be greater. However, even during the most humid periods the high altitudes typically allow for some relief from the heat overnight.

Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Dera Ismail Khan Climate chart (explanation) J F M A M J J A S O N D 1020418227352713223419173923144227613927583726183724533172281110225Average max. and min. temperatures in °C Precipitation totals in mm Source: World Climate Data[11] Imperial conversion J F M A M J J A S O N D 0.468390.772451.481550.993660.7102730.6108812.4102812.399790.799750.291630.182520.47241Average max. and min. temperatures in °F Precipitation totals in inches As one moves further away from the foothills of the Himalaya and Karakoram ranges, the climate changes from the humid subtropical climate of the foothills to the typically arid climate of Sindh, Balochistan and southern Punjab. As in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the seasonality of precipitation shows a very sharp gradient from west to east, but the whole region very rarely receives significant monsoonal rainfall. Even at high elevations annual rainfall is less than 400 millimetres (16 in) and in some places as little as 200 millimetres (8 in).

Temperatures in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are extremely hot: Dera Ismail Khan in the southernmost district of the province is known as one of the hottest places in the world with temperatures known to have reached 50 °C (122 °F). In the cooler months, however, nights can be cold and frosts remain frequent, though snow is very rare and daytime temperatures remain comfortably warm with abundant sunshine.

Administrative Districts

The province consists of the following 25 districts, including 5 Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATAs):

- Abbottabad

- Bannu

- Battagram

- Buner

- Charsadda

- Chitral (PATA)

- Dera Ismail Khan

- Hangu

- Haripur

- Karak

- Kohat

- Kohistan

- Lakki Marwat

- Lower Dir (PATA)

- Malakand (PATA)

- Mansehra

- Mardan

- Nowshera

- Peshawar

- Shangla

- Swabi

- Swat (PATA)

- Tank

- Tor Ghar

- Upper Dir (PATA)

Demographics

Historical populations Census Population Urban 1951 4,556,545 11.07% 1961 5,730,991 13.23% 1972 8,388,551 14.25% 1981 11,061,328 15.05% 1998 17,743,645 16.87% The province has an estimated population of about 21 million. The largest ethnic group is the Pashtun, historically known as ethnic Afghans, who form well over two-thirds of the population.[12] Around 1.5 Afghan refugees also remain in the province[13], majority of which are Pashtuns followed by Tajiks, Hazaras, and other smaller groups. Despite having lived in the province for over two decades, they are registered as citizens of Afghanistan.[14]

Pashto is the most pervasive language while Hindko is the second most commonly spoken indigenous language. It is predominant in western parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and is the main language in most cities and towns including Peshawar.

Hindko is mostly spoken in eastern parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Hazara Division, and especially in the cities of Abbottabad, Mansehra, and Haripur, and also as a minority in the city of Peshawar. This language is spoken by the Hindkowanwho are an indian ethnic group.some afghan tribes also speak hindko as a first language. The provincial government is planning to introduce Hindko-medium education in Peshawar, Nowshera, Kohat, Haripur, Abbottabad and Mansehra districts.[15]

In most rural areas of the centre and south various Pashtun tribes can be found including the Yusufzai, Bhittani, Daavi, Khattak, Babar, Gandapur, Gharghasht, Marwat, Afridi, Tanoli, Shinwari, Orakzai, Bangash, Mahsud, Mohmand, and Wazir as well as numerous other pushtun tribes of Hazara division •, Swati, Kakar, Tareen, Jadoon and Mashwani. There are various non-Pashtun tribes including Mughal, Turks, Gujjar,Gujjar are also main tribe of Khaber pukhtoonkhwa,majority of the gujjar tribe has been further divede into different su-clan they speak pushtoo and write their cast afghan because some of them migrated from afghanistan and settled across the province, pukthoon concider these people as non pukhtoon tribe.Gujjar in afghanistan count 35 percent of the total population majority of them speak pushtoo and other languages.In pakistan punjab,sindh karachi,kashmir they are main ethnic group and Enjoing high positions in governament. in India gujjar are have high ranking tribes and ethnic group of baharath,they follow muslim relgion, hidusim and sikism. Karlal, Rajpoot, Dhund Abbasi, Syed, Kashmiri, Awan, Qureshi and Sarrara.Kaka khels, Akhund Khel Akhund is the title given to any chief of special sanctity, Many Akhund Khels are Yousafzai Many Akhunkhels are Syeds. The Syed Akhunkhel Mians, enjoy special respect amongst the peoples on account of their ancestry. These individuals were religious people who traveled many years back and the Pukhtons welcomed and honored them. Visits to shrines or ziarats were very common especially by the women. Syed (Akhunkhel) is a respectable family of Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa who are known for their religious background. The mountainous extreme north includes the Chitral and Kohistan districts that are home to diverse Dardic ethnic groups such as the Khowar, Kohistani, Shina, Torwali, Kalasha and Kalami. However in the southern-most district live some of the Baloch tribe: Kori[disambiguation needed

], Buzdar, Kunara, Leghari, Rind and some other sub tribes of Lashari tribe. These Baloch tribes speak Saraiki as their first language. In this southern district, most of its population speaks Saraiki. Nearly all of the inhabitants of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa profess Islam, with a Sunni majority and significant minorities of Shias and Ismailis. Many of the Kalasha of Southern Chitral still retain their ancient Animist/Shamanist religion.

], Buzdar, Kunara, Leghari, Rind and some other sub tribes of Lashari tribe. These Baloch tribes speak Saraiki as their first language. In this southern district, most of its population speaks Saraiki. Nearly all of the inhabitants of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa profess Islam, with a Sunni majority and significant minorities of Shias and Ismailis. Many of the Kalasha of Southern Chitral still retain their ancient Animist/Shamanist religion.History

Main article: History of Khyber PakhtunkhwaAncient history

Since ancient times the region numerous groups have invaded Khyber Pakhtunkhwa including the Persians, Greeks, Scythians, Kushans, Huns, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, Mughals, and the British. Between 2000 and 1500 BC, the Aryans split off into an Iranian branch, represented by the Pushtuns who came to dominate most of the region, an Indo-Aryan branch represented by the Hindkowans who populated much of the region before the time of the Pashtuns and various Dardic peoples who came to populate much of the north. Earlier pre-Aryan inhabitants include the Shin or shinwaris and Burusho. The region is mentioned in the Mahabharatha epic as Gandhara Kingdom and lied in the outer fringes of Bharatvarsha. The Vale of Peshawar was home to the Kingdom of Gandhara probably from around the 6th century BC. It was known for its Hindu and Buddhist heritage. It was part of Nanda, Mauryan and Sunga empire before being overrun by foreigners. Ancient Peshawar then known as Purushupura became a capital of the Kushan Empire. The region was visited by such notable historical figures as Darius II, Hsuan Tsang, Fa Hsien, Marco Polo, and Mountstuart Elphinstone, among others. Following the Mauryan conquest of the region, Buddhism became a major faith, at least in urban centres, as attested by recent archaeological and hermeneutic evidence. Kanishka, a prominent Kushan ruler was one of the prominent Buddhist kings.

“ The region of Gandhara has long been known as a major centre of Buddhist art and culture around the beginning of the Christian era. But until recently, the Buddhist literature of this region was almost entirely lost. Now, within the last decade, a large corpus of Gandharan manuscripts dating from as early as the 1st century A.D. has come to light and is being studied and published by scholars at the University of Washington. These scrolls, written on birch-bark in the Gandharan language and the Kharosthi script, are the oldest surviving Buddhist literature, which has hitherto been known to us only from later and modern Buddhist canons. They also institute a missing link between original South Asian Buddhism and the Buddhism of East Asia, which was exported primarily from Gandhara along the Silk Roads through Central Asia and thence to China.[16] ” Rural areas retained numerous Shamanistic faiths as evident with the Kalash and other groups. The roots of Pashtunwali or the traditional code of honor followed by the Pashtuns is also believed to have Pre-Islamic origins. Persian invasions left small pockets of Zoroastrians and, later, a ruling Hindu elite established itself during the later Shahi period.

The Shahi era

During the early 1st millennium, prior to the arrival of Muslims, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region was ruled by the Shahi kings. The early Shahis were Buddhist rulers and reigned over the area until 870 CE when they were overthrown and then later replaced.

When the Chinese monk Xuanzang visited the region early in the 7th century CE, the Kabul valley region was still ruled by affiliates of the Shahi kings, who is identified as the Shahi Khingal, and whose name has been found in an inscription found in Gardez.

While the early Shahis were Turko-Iranian and Kabulistani in origin referred as Kushano-Hepthalites, the later Shahi kings of Kabul and Gandhara were Hindu and had links to some ruling families in neighbouring Kashmir and the Punjab. The Hindu Shahis are believed to have been a ruling elite of a predominantly Buddhist, Hindu and Shamanistic population and were thus patrons of numerous faiths, and various artefacts and coins from their rule have been found that display their multicultural domain.

The last Shahi rulers were eventually wiped out by Mahmud of Ghazni in the early 11th century AD.

Arrival of Islam

Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Shamanism were the prominent in the region until Muslim Arabs and Turks conquered the area before the 2nd millennium CE[citation needed]. Over the centuries several migrations took place by the local population consisting majorly of Hindus and Buddhists while the remaining were converted to Islam. Local Pashtun and Dardic tribes converted to Islam, while retaining some local traditions (albeit altered by Islam) such as Pashtunwali or the Pashtun code of honor.

Between 963 and 1187 AD the area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa became part of larger Islamic empires, including the Ghaznavid Empire (975-1187), headed by Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, and the empire of Muhammad Shahabuddin Ghauri (reigned 1202-1206). The Ghaznavid domain included Afghanistan extending up to Punjab and parts of the Indian subcontinent, with its capital at Lahore from 1151 to 1186.

Later the Afghan Pashtun Muslims of the Delhi Sultanate controlled the region. (The "Delhi Sultanate" refers to the many Muslim states that ruled in India from 1206 to 1526.)

Several Turkic and Afghan dynasties ruled from Delhi instead of from Lahore: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90), the Khilji dynasty (1290–1320), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1413), the Sayyid dynasty (1414–51), and the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526).

Mughal Empire

In 1526 the Delhi Sultanate was absorbed by the emerging Mughal Empire and the Ilkhanate Empire of the Turks, coming from Great Timur Lang and his grandsons like Babur the Mughal Dynasty.

Muslim technocrats, bureaucrats, soldiers, traders, scientists, architects, teachers, theologians and sufis flocked from the rest of the Muslim world to the region and Islam flourished because of these Northern Afghan and Central Asian invaders.

Afghan control

The area formed part of the Durrani Empire founded by Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1747. Ahmed Shah Durrani was born in Kabul which was at that time part of Afghanistan. The empire included Bahwalpur, Kashmir, Gilgit, Hazara with its main city Haripur. Under Ahmed Shah Durrani and later his son Timur Shah, who ruled from Lahore and Multan, but later shifted it back to Kandahar.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was an important iranian borderland that was often contested by the Mughals and Safavids who considered it part of their land. During the reign of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa required formidable military forces to control and the emergence of Pashtun nationalism, who opposed Mughals who were trying to infiltrate it from India across the Indus River. A leading force in inspiring Pashtun miltancy was the local warrier poet Khushal Khan Khattak who united some of the tribes against the various empires around the region.

As the Mughal had lost control by 1757, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa came under the control of the Amir of Afghanistan Ahmad Shah Abdali.

Sikh rule

Most of the region referred to in the twenty first century as the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa came under Sikh rule in the first half of the nineteenth century, when the Sikhs gained control of Peshawar.[17]

The Afghans governed Hazara-i-Karlugh, Gandhgarh and the Gakhar territory from Attock; while Kashmir collected the revenue from the upper regions of Pakhli, Damtaur and Darband. In 1813, the Sikhs conquered the fort of Attock, at which time lower Hazara became tributary to them. Upper Hazara shared the same fate in 1819, when the Sikhs conquered Kashmir. The territory referred to as Hazara formed when Maharaja Ranjit Singh bestowed the area as a jagir on Hari Singh Nalwa, Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh army, in 1822.[18]

The Sikhs forayed into Peshawar for the first time in 1818, but did not occupy the territory. In 1823, following the Battle of Naushehra on the banks of the Kabul river, Hari Singh Nalwa and his men chased the Afghans first to Peshawar and then to the mouth of the Khyber Pass. The Sikhs entered the city of Peshawar for a second time, once again affirming to hold Peshawar as a tributary to the Sikh Court of Lahore. After plundering the city they burnt its fortress, the Bala Hissar.[19] The Sikh occupation of Peshawar in 1834, was executed in a most unusual manner.[20] By 1836, with the conquest of Jamrud the frontier of the Sikh Kingdom bordered the foothills of the Hindu Kush Mountains and the Khyber Pass formed its western boundary.[21] However the death of sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa at Battle of Jamrud spelt a blow to Sikh forward advance policy and their wish to conquer Kabul. The death of King Ranjit Singh in 1839 plunged the Sikh kingdom into turmoil and after the loss in 2 Anglo-Sikh wars, British took direct control of the region.

The most significant contributions of Sikh rule to this region were the city of Haripur, the first planned city in this entire region, and the forts of Sumergarh (Bala Hissar, Peshawar) and Fatehgarh (Fort of Jamrud at the mouth of the Khyber Pass).[22]

The British Raj and the Durand Line Agreement

Main article: Durand LineAfghanistan before the Durand agreement of 1893.

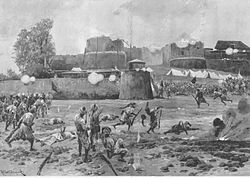

Afghan tribesmen attacking the British-held Shabkadr Fort outside Peshawar in 1897

Afghan tribesmen attacking the British-held Shabkadr Fort outside Peshawar in 1897

The British, who had captured most of the subcontinent without significant problems,[dubious ] faced a number of difficulties here. However, crossing the Indus River on to the Iranian plateau and Pushtun territory which lay there gave them a new type of challenge. The Pashtuns, strong in their belief that they must defend their land from foreign incursion, resisted the British advancement. The first war between British and the Pashtuns resulted in a devastating defeat for the British, with just one individual, Dr. William Brydon coming back alive (out of a total of 14,800-21,000 people). This happened during the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1849 and later the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1876. The Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919, was also a continuation of the fight for Reclaiming Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and claiming independence from British occupation efforts which the Afghans or the Pashtuns resisted with greatest zeal and effort to remain as independent nation.

Unable to enforce their rule and invade these territories fully in the region, the British changed their tactics and played a game of divide and rule. They exploited religious differences, installed puppet Pushtun rulers, divided the Pashtuns through artificially-created regions, and ruled indirectly to reduce the chance of confrontation between Pashtuns and themselves. Although the smallest size province Pushtoons were divided into Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATA), Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), Frontier Regions (FR) and Settled Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was restricted to five districts.

Occasional Pushtun resistance and attacks did take place on British in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including the Siege of Malakand and Swat, both well documented by Winston Churchill who was a war correspondent at the time.

A series of conflicts known as the Anglo-Afghan Wars during the imperialist Great Game, wars between the British and Russian governments, led to the eventual dismemberment of Afghanistan into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Baluchistan and Khurasan. Divide and rule policy and the annexation of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan region led to the demarcation of the Durand Line and administration as part of British India.

The Durand line is a poorly marked 1,519-mile (2,445 km) border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. After fighting in two wars against Afghans, the British succeeded in 1893 in imposing the Durand line, dividing Afghanistan from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Baluchistan, FR regions, FATA which were incorporated into what was then British India. It was agreed upon by representatives of both governments.

The international boundary line separating two countries was named after Sir Mortimer Durand, foreign secretary of the British colonial government, who in 1893 had negotiated with Abdur Rahman Khan, the Amir of Afghanistan, on the frontier between modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Areas annexed from Afghanistan were the FATA, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces of Pakistan, the successor state of British India and the successor Iranian state of Khorasan.

In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand was sent to Kabul by the government of British India for the purpose of settling an exchange of territory required by the demarcation of the boundary between northeastern Afghanistan, Iran and the Russian possessions.

The Amir showed ability in diplomatic argument, his tenacity where his own views or claims were in debate, with a sure underlying insight into the real situation. The territorial exchanges were amicably agreed upon; the relations between the British Indian and Afghan governments, as previously arranged, were confirmed; and an understanding was reached upon the important and difficult subject of the border line of Afghanistan on the east, towards India.

From the British side the camp was attended by Sir Mortimer Durand and Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum the, Political Agent for the Khyber Agency. Afghanistan was represented by Sahibzada Abdul Latif and the Governor Sardar Shireendil Khan representing the King Amir Abdur Rahman Khan.[23]

While the Afghan side greatly resented the border and viewed it as a temporary development, the British viewed it as being a permanent settlement. The North-West Frontier Province was formed on November 9, 1901, as a Chief Commissioner ruled province, the Chief Commissioner was the chief executive of the province.

He ran the administration with the help of his principal advisers and Civil servants better known as judicial and Revenue Commissioners.

The formal inauguration of the province took place five and half months later, at Shahi Bagh on April 26, 1902, on the occasion of the historical Darbar in the Shahi Bagh (Kings Garden) in the capital town of Peshawar.

It was held by Lord Curzon the Governor of the North-West Frontier Province. The province then comprised only five districts after dividing annexed areas from Afghanistan into FATA, Frontier Regions and the North-West Frontier Province and Southern Punjab.

North-West Frontier Province districts were Peshawar District, Hazara District, Kohat District, Bannu District and the Dera Ismail Khan District.

The first Chief Commissioner of the North-West Frontier Province was Harold Deane. He was known as a strong administrator and he was succeeded by Ross-Keppel, in 1908, whose contribution as a political officer was widely known amongst the tribal/frontier people.

North-West Frontier Province was raised to a full-fledged governor-ruled province in 1931 in accordance with the demand by the Round Table Conference held in 1931. It was agreed upon in the conference that the North-West Frontier Province would be raised to a governor-ruled province with its own Legislative Council. Sir Ralph Griffith was appointed the first Governor in 1932 (having succeeded Stuart Pearks as Chief Commissioner in 1931).

Therefore, on January 25, 1932, the Viceroy inaugurated the first North-West Frontier Province Legislative Council. The first provincial elections were held in 1937 and the independent candidate and noted British loyal civil servant Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum was elected as the province's first Chief Minister.

After independence

During the early 20th century the so-called Red Shirts led by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan agitated through Non-violence for the rights of Pashtun areas.

Following independence, the North-West Frontier Province voted to join Pakistan in a referendum in 1947. However, Afghanistan's loya jirga of 1949 declared the Durand Line invalid, which led to border tensions with Pakistan. Afghanistan's governments have periodically refused to recognize Pakistan's inheritance of British treaties regarding the region, leading to a counter-claim by Pakistan that the original treaties, if they must be discussed, can only be held with the original signer, the Kingdom of Afghanistan, which is now defunct - essentially denying modern Afghanistan the same sort of inheritance rights that it denies Pakistan.

During the 1950s, Afghanistan supported the Pushtunistan Movement, a secessionist movement that failed to gain substantial support amongst the tribes of the North-West Frontier Province. Afghanistan's refusal to recognize the Durrand Line, and its subsequent support for the Pashtunistan Movement has been cited as the main cause of tensions between the two countries that have existed since Pakistan's independence.

After Ayub Khan eliminated Pakistan's provinces, Yahya Khan, in 1969, abolished this "one unit" scheme and added Amb, Swat, Dir, Chitral and Kohistan to the new North-West Frontier Province as the Provincially Administered Tribal Areas.

Afghan jihad and war with the USSR

During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (1979-1989) the North-West Frontier Province served as a major base for supplying the Mujahideen who fought the Soviets during the 1980s.

Following the arrival of Soviet forces, over five million Afghan refugees poured into Pakistan, most residing in the North-West Frontier Province (as of 2007, nearly 3 million remained).

The North-West Frontier Province remained heavily influenced by events in Afghanistan. Civil war in Afghanistan (1989-1992) led to the rise of the Taliban, which had emerged in the border region between Afghanistan, Baluchistan, PATA and FATA as a formidable political force. Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the FATA and bordering North-West Frontier Province became a front-line region again, as part of the global "War on Terror".

In 2010 the name of the province changed to "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". Protests arose among the local ethnic Hazara population due to this name change, as they began to demand their own province. Seven people were killed and 100 injured in protests on 11 April 2011.[24]

Provincial government

Provincial symbols of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (unofficial) Provincial animal Kabul Markhor

Provincial bird White-crested Kalij Pheasant

Provincial tree Juniperus squamata

Provincial flower Morina  Main article: Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Main article: Government of Khyber PakhtunkhwaThe Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is unicameral and consists of 124 seats of which 2% are reserved for non-Muslims and 17% for women only.

The President of Pakistan appoints a Governor as head of the provincial government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. There is a directly-elected Provincial Assembly, which has 124 elected members (including 22 seats reserved for women and 3 seats for non-Muslims). The Provincial Assembly elects a Chief Minister to act as the chief executive of the province, assisted by a cabinet of ministers.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is divided into 25 districts, comprising 20 Settled Area Districts and 5 Provincially Administered Tribal Area (PATA) Districts. The administration of the PATA districts is vested in the President of Pakistan and the Governor of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, by Articles 246 and 247 of the Constitution of Pakistan.[25]

The 25 districts are: - Abbottabad

- Bannu

- Batagram

- Buner

- Charsadda

Important cities

- Abbottabad

- Bannu

- Balakot

- Besham

- Batagram

- Daggar

TOR GHAR(kala dhaka)

Economy

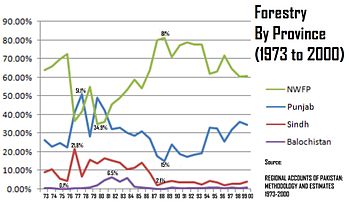

Main article: Economy of Khyber PakhtunkhwaKhyber Pakhtunkhwa's share of Pakistan's GDP has historically comprised 10.5%, although the province accounts for 11.9% of Pakistan's total population, rendering it the second-poorest province after neighboring Balochistan. The part of the economy that Khyber Pakhtunkhwa dominates is forestry, where its share has historically ranged from a low of 34.9% to a high of 81%, giving an average of 61.56%.[26] Currently, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa accounts for 10% of Pakistan's GDP,[27] 20% of Pakistan's mining output[28] and since 1972, it has seen its economy grow in size by 3.6 times.[29]

After suffering for decades due to the fallout of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, today they are again are being targeted for totally a different situation of terrorism.

Agriculture remains important and the main cash crops include wheat, maize, Tobacco (in Swabi), rice, sugar beets, as well as various fruits are grown in the province.

Some manufacturing and high tech investments in Peshawar has helped improve job prospects for many locals, while trade in the province involves nearly every product. The bazaars in the province are renowned throughout Pakistan. Unemployment has been reduced due to establishment of industrial zones.

Numerous workshops throughout the province support the manufacture of small arms and weapons of various types. The province accounts for at least 78% of the marble production in Pakistan.[30]

Social issues

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has the second-lowest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces, at 0.607.[31] Furthermore, it also continues to have an image problem. Even within Pakistan it is regarded as a "radical state" due to the rise of Islamist parties in the province and purported support for the remnants of the Taliban,[citation needed]. Some people[who?] believe that Taliban members have gone into hiding in the province.

The Awami National Party sought[when?] to rename the province "Pakhtunkhwa", which translates to "Land of Pakhtuns" in the Pashto language. This was opposed by some of the non-Pashtuns, and especially by parties such as the Pakistan Muslim League-N (PML-N) and Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA). The PML-N derives its support in the province from primarily non-Pashtun Hazara regions.

In 2010 the announcement that the province would have a new name led to a wave of protests in the Hazara region.[32] On April 15, 2010 Pakistan's senate officially named the province "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa" - with 80 senators in favor and 12 opposed.[33] The MMA, who until the elections of 2008 had a majority in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, had proposed "Afghania" as a compromise name.[34]

After the 2008 general election, the Awami National Party formed a coalition provincial government with the Pakistan Peoples Party.[35] The Awami National Party has its strongholds in the Pashtun areas of Pakistan, particularly in the Peshawar valley, while Karachi in Sindh has one of the largest Pashtun populations in the world - around 7 million by some estimates.[36] In the 2008 election the ANP won two Sindh assembly seats in Karachi. The Awami National Party has been instrumental in fighting the Taliban.[37]

Corruption

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has suffered from worst corruption ever since Pakistan came into bieng. Jobs are sold and new jobs aren't announced despite of the fact that several thousand of seats in different sectors are vacant. There is no Body in the province that could keep a watch on corruption. The Courts in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province are known for its lack of decision making capacity.

Folk music

Hindko and Pashto folk music are popular in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and has a rich tradition going back hundreds of years. The main instruments are the Rubab, mangey and harmonium.

Khowar folk music is popular in Chitral and northern Swat. The tunes of Khowar music are very different from those of Pashto and the main instrument is the Chitrali Sitar.

A form of band music composed of clarinets (surnai) and drums is popular in Chitral. It is played at polo matches and dances. The same form of band music is also played in the neighbouring Northern Areas.

Education

The trend towards higher education is rapidly increasing in the province and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is home to Pakistan's foremost engineering university (Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology), which is located in Topi, a town in Swabi district. The University of Peshawar is also a notable institution of higher learning. The Frontier Post is perhaps the province's best-known newspaper and addresses many of the various issues facing the local population.

Year Literacy Rate 1972 15.5% 1981 16.7% 1998 35.41% 2008 49.9% This is a chart of the education market of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa estimated by the government in 1998. Also see[40]

Qualification Urban Rural Total Enrolment Ratio(%) — 2,994,084 14,749,561 17,743,645 — Below Primary 413,782 3,252,278 3,666,060 100.00 Primary 741,035 4,646,111 5,387,146 79.33 Middle 613,188 2,911,563 3,524,751 48.97 Matriculation 647,919 2,573,798 3,221,717 29.11 Intermediate 272,761 728,628 1,001,389 10.95 BA, BSc… degrees 20,359 42,773 63,132 5.31 MA, MSc… degrees 18,237 35,989 53,226 4.95 Diploma, Certificate… 82,037 165,195 247,232 1.92 Other qualifications 19,766 75,226 94,992 0.53 Major educational establishments

- Abbottabad Public School, Abbottabad

- University of Swat, Saidu Sharif Swat[41]

- Abdul Wali Khan University,[citation needed] Mardan

- Army Burn Hall College, Abbottabad

- Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad

- Ayub Dental College, Abbottabad

- Bacha Khan Medical College,[citation needed] Mardan

- Pakistan International Public School and College, Abbottabad[42]

- Women Medical College,[citation needed] Abbottabad

- Bannu Medical College,[citation needed] Bannu

- Cadet College Razmak, Razmak

- Cadet College Kohat, Kohat

- Cadet College Batrasi, Mansehra

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad Campus

- Gandhara University, Peshawar

- Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, Topi, Swabi

- Gomal Medical College, D. I. Khan

- Gomal University, Dera Ismail Khan

- Hazara University, Mansehra

- Islamia College, Peshawar

- Khyber College of Dentistry, Peshawar

- Khyber Medical College, Peshawar

- Khyber Medical University, Peshawar

- Khyber Girls Medical College, Peshawar

- Kabir Medical College, Peshawar

- Kohat University of Science & Technology, Kohat

- KUST Institute of Medical Sciences, Kohat

- Military College of Engineering, Risalpur

- National Institute of Transportation, Risalpur

- National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Peshawar Campus

- NWFP University of Agriculture, Peshawar

- Pakistan Air Force Academy, Risalpur

- Pakistan Military Academy, Abbottabad

- Saidu Medical College, Swat

- Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal

- University of Engineering and Technology, Peshawar

- University of Malakand, Chakdara

- University of Peshawar, Peshawar

- University of Science & Technology Bannu, Bannu

See also

- Federally Administered Tribal Areas

- Kakazai

- Provincially Administered Tribal Areas

- Frontier Regions

- North-West Frontier (military history)

- Pashtunistan

- Durand line

- 2010 Pakistan floods

References

- ^ http://tribune.com.pk/story/116200/masood-kausar-appointed-k-p-governor-national/

- ^ "Centenary Celebrations of N.W.F.P. - Government of Pakistan". Pakpost.gov.pk. http://www.pakpost.gov.pk/philately/stamps2003/centenary_celebrations_of_nwpf.html. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (province, Pakistan) :: Geography - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/419493/Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa/249136/Geography. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ http://www.stratfor.com/files/mmf/5/6/566d754dc7fd57ce4263e14dc24eccc80b369acd.jpg

- ^ "District wise area and population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". http://www.nwfpbos.sdnpk.org/nwfpds/2000/5.htm.

- ^ "North-West Frontier Province - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 19, p. 147". Dsal.uchicago.edu. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?objectid=DS405.1.I34_V19_153.gif. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ a b Mock, John and O'Neil, Kimberley; Trekking in the Karakoram and Hindukush; p. 15 ISBN 0-86442-360-8

- ^ Mock and O'Neil; Trekking in the Karakoram and Hindukush; pp. 18-19

- ^ "World Climate Data: Dir, Pakistan". Weatherbase. 2010. http://www.climate-charts.com/Locations/p/PK41508.php. Retrieved 1 September.

- ^ a b See Wernsted, Frederick L.; World Climatic Data; published 1972 by Climatic Data Press; 522 p. 31 cm.

- ^ "World Climate Data: Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan". Weatherbase. 2010. http://www.climate-charts.com/Locations/p/PK41624.php. Retrieved 1 September.

- ^ People and culture - Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa[dead link]

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2008-04-30). "Pakistani TV delves into lives of Afghan refugees". UNHCR. http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/481856844.html. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ UNHCR country operations profile - Pakistan

- ^ "Work Under Way on Hindko Curriculum". http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/the-newspaper/local/peshawar/work-under-way-on-hindko-curriculum-200. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ Lecture: " Rediscovering the lost Buddhist literature of Gandhara" by Prof. Richard Salomon, University of Washington, Seattle at Stanford University (2005)

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 77-104, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, p. 102, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ National Archives of India, Foreign Secret Consultation, 29-10-1824: 9.

- ^ Masson, Charles. 1842. Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, London: Richard Bentley, v.3, 224-9.

- ^ National Archives of India, Foreign Secret Consultation, 6-3-1837: 14

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ http://www.aaiil.org/aaiil/ra/jalsa/2003/sahibzadaabdullatifshaheed100anniversary/08sahibzadazahoorahmad_sahibzadaabdullatifshaheed. mp3

- ^ "Anti-Pakhtunkhwa protest claims 7 lives in Abbottabad". The Statesmen. 13 April 2011. http://www.thestatesmen.net/news/anti-pakhtunkhwa-protest-claims-seven-lives-in-abbottabad. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ "The Constitution". Government of Pakistan. http://www.ljcp.gov.pk/Menu%20Items/1973%20Constitution/constitution.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973-2000" (PDF). http://www.spdc.org.pk/pubs/nps/nps5.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Roman, David (2009-05-15). "Pakistan's Taliban Fight Threatens Key Economic Zone - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124237648756523343.html?mod=googlenews_wsj. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Pakistan May Need Extra Bailouts as War Hits Economy (Update2)". Bloomberg.com. 2009-06-15. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601091&sid=a4Jvjhis1L70. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "World Bank Document" (PDF). http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PAKISTANEXTN/Resources/293051-1241610364594/6097548-1257441952102/balochistaneconomicreportvol2.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "World Bank Pakistan Growth and Export Competitiveness" (PDF). http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2006/05/23/000012009_20060523095241/Rendered/PDF/354991PK0rev0pdf.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ http://www.spdc.org.pk/pubs/rr/rr73.pdf

- ^ "Protest in Hazara continues over renaming of NWFP to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". App.com.pk. http://www.app.com.pk/en_/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=99951&Itemid=2. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "NWFP officially renamed as Pakhtun HAZARA". Dawn.com. 15 April 2010. http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/news/pakistan/07-senate-begins-voting-on-18th-amendment-ha-02. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "MMA govt proposes new name for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (then NWFP)". Dawn. http://www.dawn.com/2007/08/01/top11.htm.

- ^ Abbas, Hassan. "Peace in FATA: ANP Can Be Counted On." Statesman (Pakistan) (2007 Feb 4).

- ^ PBS Frontline: Pakistan: Karachi's Invisible Enemy City potent refuge for Taliban fighters. July 17, 2009.

- ^ "Pakistan's 'Gandhi' party takes on Taliban, Al Qaeda". CSMonitor.com. 2008-05-05. http://www.csmonitor.com/2008/0505/p06s01-wosc.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Pakistan: where and who are the world's illiterates?; Background paper for the Education for all global monitoring report 2006: literacy for life; 2005" (PDF). http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001459/145959e.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ http://www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/fbs/publications/lfs2007_08/results.pdf

- ^ "Population Census Organization, Government of Pakistan". Statpak.gov.pk. http://www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/pco/statistics/pop_by_province/pop_by_province.html. Retrieved 2010-05-25.[dead link]

- ^ http://www.swatuniversity.edu.pk

- ^ www.hazara.com.pk

External links

- Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa at the Open Directory Project

- North-West Frontier Province travel guide from Wikitravel

- http://www.pukhtunkhwa.com

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa topics

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa topicsHistory Gandhara · History of Peshawar · History of Malakand · British period · Durand Line · Names of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa · Durrani Empire · Soviet war in AfghanistanGovernment

and politicsProvincial Assembly · Chief Minister · Governor · Jirga · Loya jirga · Taliban · Awami National Party · EconomyCulture and

placesPashtun people (List) · Pashtun tribes · Culture · Language · Cuisine · Pashtunwali · Pashtunization · Diaspora · Dress · Pashtun tribal structure · Afghan (name) · Pashtun names · Music · Media · Literature and poetry (List of poets) · Alphabet · Grammar · Dialects · Pollywood (List of films) · Singers · List of television channels · Hindkowan people · Hindko language · Afghan refugeesGeography List of cities · Districts · Pashtunistan · Hazara · Provincially Administered Tribal Areas · Khyber PassEducation Sport Provinces and administrative units of Pakistan Provinces

Territories Kashmir See also: Former administrative units of PakistanDistricts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa  Categories:

Categories:- Provinces of Pakistan

- Durand line

- 2005 Kashmir earthquake

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- States and territories established in 1970

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.