- Mehrgarh

-

The Neolithic

↑ Mesolithic - Europe

- Boian culture

- Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

- Linear Pottery Culture

- Malta Temples

- Sesklo Culture

- Varna culture

- Vinča culture

- Vučedol culture

- China

- Korea

- South Asia

- Mehrgarh

- Mehrgarh

farming, animal husbandry

pottery, metallurgy, wheel

circular ditches, henges, megaliths

Neolithic religion↓ Chalcolithic History of South Asia and India - Mehrgarh Culture (7000–3300 BCE)

- Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1700 BCE)

- Early Harappan Culture (3300–2600 BCE)

- Mature Harappan Culture (2600–1900 BCE)

- Late Harappan Culture (1700–1300 BCE)

- Ochre Coloured Pottery culture (from 2000 BCE)

- Swat culture (1600–500 BCE)

- Vedic Civilization (2000–500 BCE)

- Black and Red ware culture (1300–1000 BCE)

- Painted Grey Ware culture (1200–600 BCE)

- Northern Black Polished Ware (700–200 BCE)

- Maha Janapadas (700–300 BCE)

- Magadha Empire (684–424 BCE)

- Nanda Empire (424–321 BCE)

- Chera Empire (300 BCE–1200 CE)

- Chola Empire (300 BCE–1279 CE)

- Pandyan Empire (300 BCE–1345 CE)

- Maurya Empire (321–184 BCE)

- Pallava Empire (250 BCE–800 CE)

- Sunga Empire (185–73 BCE)

- Kanva Empire (75–26 BCE)

- Maha-Megha-Vahana Empire (250s BCE–400s CE)

- Satavahana Empire (230–220 BCE)

- Kuninda Kingdom (200s BCE–300s CE)

- Indo-Scythian Kingdom (200 BCE–400 CE)

- Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BCE–10 CE)

- Indo-Parthian Kingdom (21–130s CE)

- Western Satrap Empire (35–405 CE)

- Kushan Empire (60–240 CE)

- Indo-Sassanid Kingdom (230–360 CE)

- Vakataka Empire (250s–500s CE)

- Kalabhras Empire (250–600 CE)

- Gupta Empire (280–550 CE)

- Kadamba Empire (345–525 CE)

- Western Ganga Kingdom (350–1000 CE)

- Kamarupa Kingdom (350–1100 CE)

- Vishnukundina Empire (420–624 CE)

- Maitraka Empire (475–767 CE)

- Huna Kingdom (475–576 CE)

- Rai Kingdom (489–632 CE)

- Chalukya Empire (543–753 CE)

- Shahi Empire (500s–1026 CE)

- Maukhari Empire (550s–700s CE)

- Harsha Empire (590–647 CE)

- Eastern Chalukya Kingdom (624–1075 CE)

- Gurjara Pratihara Empire (650–1036 CE)

- Pala Empire (750–1174 CE)

- Rashtrakuta Empire (753–982 CE)

- Paramara Kingdom (800–1327 CE)

- Yadava Empire (850–1334 CE)

- Solanki Kingdom (942–1244 CE)

- Western Chalukya Empire (973–1189 CE)

- Hoysala Empire (1040–1346 CE)

- Sena Empire (1070–1230 CE)

- Eastern Ganga Empire (1078–1434 CE)

- Kakatiya Kingdom (1083–1323 CE)

- Kalachuri Empire (1130–1184 CE)

- Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE)

- Ahom Kingdom (1228–1826 CE)

- Reddy Kingdom (1325–1448 CE)

- Vijayanagara Empire (1336–1646 CE)

- Gajapati Kingdom (1434–1541 CE)

- Deccan Sultanates (1490–1596 CE)

- Mughal Empire (1526–1858 CE)

- Maratha Empire (1674–1818 CE)

- Durrani Empire (1747–1823 CE)

- Sikh Empire (1799–1849 CE)

Regional states (1102–1947 CE)- Zamorin Kingdom (1102–1766 CE)

- Deva Kingdom (1200s–1300s CE)

- Chitradurga Kingdom (1300–1779 CE)

- Garhwal Kingdom (1358–1803 CE)

- Mysore Kingdom (1399–1947 CE)

- Keladi Kingdom (1499–1763 CE)

- Koch Kingdom (1515–1947 CE)

- Thondaiman Kingdom (1650–1948 CE)

- Madurai Kingdom (1559–1736 CE)

- Thanjavur Kingdom (1572–1918 CE)

- Marava Kingdom (1600–1750 CE)

- Sikh Confederacy (1707–1799 CE)

- Travancore Kingdom (1729–1947 CE)

- Portuguese India (1510–1961 CE)

- Dutch India (1605–1825 CE)

- Danish India (1620–1869 CE)

- French India (1759–1954 CE)

- Company Raj (1757–1858 CE)

- British Raj (1858–1947 CE)

- Partition of India (1947 CE)

- Kingdom of Tambapanni (543–505 BCE)

- Kingdom of Upatissa Nuwara (505–377 BCE)

- Kingdom of Anuradhapura (377 BCE–1017 CE)

- Kingdom of Ruhuna (200 CE)

- Polonnaruwa Kingdom (300–1310 CE)

- Kingdom of Dambadeniya (1220–1272 CE)

- Kingdom of Yapahuwa (1272–1293 CE)

- Kingdom of Kurunegala (1293–1341 CE)

- Kingdom of Gampola (1341–1347 CE)

- Kingdom of Raigama (1347–1415 CE)

- Kingdom of Kotte (1412–1597 CE)

- Kingdom of Sitawaka (1521–1594 CE)

- Kingdom of Kandy (1469–1815 CE)

- Portuguese Ceylon (1505–1658 CE)

- Dutch Ceylon (1656–1796 CE)

- British Ceylon (1815–1948 CE)

Nation histories- Afghanistan

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- India

- Maldives

- Nepal

- Pakistan

Regional histories- Assam

- Bihar

- Balochistan

- Bengal

- Himachal Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Uttar Pradesh

- Pakistani Regions

- Punjab

- NWFP

- Orissa

- Sindh

- South India

- Tibet

Early farming village in Mehrgarh, c. 7000 BCE, with houses built with mud bricks. (Musée Guimet, Paris).

Early farming village in Mehrgarh, c. 7000 BCE, with houses built with mud bricks. (Musée Guimet, Paris).

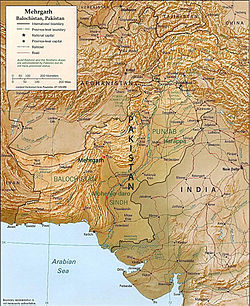

Mehrgarh (Brahui: Mehrgaŕh, Urdu: مہرگڑھ), one of the most important Neolithic (7000 BCE to c. 2500 BCE) sites in archaeology, lies on the "Kachi plain" of Balochistan, Pakistan. It is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming (wheat and barley) and herding (cattle, sheep and goats) in South Asia."[1]

Mehrgarh is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River valley and between the Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi. The site was discovered in 1974 by an archaeological team directed by French archaeologist Jean-François Jarrige, and was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986, and again from 1997 to 2000. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh—in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site—was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE to 5500 BCE and the whole area covers a number of successive settlements. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected.[2]

Contents

Lifestyle and technology

Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BCE to 2600 BCE) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working. The site was occupied continuously until about 2600 BCE.[3] Mehrgarh is probably the earliest known center of agriculture in South Asia.[4]

In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence in human history for the drilling of teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh.[5]

Archaeological significance

Mehrgarh is now seen as a precursor to the Indus Valley Civilization. "Discoveries at Mehrgarh changed the entire concept of the Indus civilization," according to Ahmad Hasan Dani, professor emeritus of archaeology at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, "There we have the whole sequence, right from the beginning of settled village life." According to Catherine Jarrige of the Centre for Archaeological Research Indus Baluchistan at the Musée Guimet in Paris:

"…the Kachi plain and in the Bolan basin (are) situated at the Bolan peak pass, one of the main routes connecting southern Afghanistan, eastern Iran, the Balochistan hills and the Indus River valley. This area of rolling hills is thus located on the western edge of the Indus valley, where, around 2500 BCE, a large urban civilization emerged at the same time as those of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Egypt. For the first time in the Indian Subcontinent, a continuous sequence of dwelling-sites has been established from 7000 BCE to 500 BCE, (as a result of the) explorations in Pirak from 1968 to 1974; in Mehrgarh from 1975 to 1985; and of Nausharo from 1985 to 1996."

The chalcolithic people of Mehrgarh also had contacts with contemporaneous cultures in northern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran and southern central Asia.[6]

Periods of occupation

Archaeologists divide the occupation at the site into several periods.

Mehrgarh Period I

Mehrgarh Period I 7000 BCE–5500 BCE, was Neolithic and aceramic (i.e., without the use of pottery). The earliest farming in the area was developed by semi-nomadic people using plants such as wheat and barley and animals such as sheep, goats and cattle. The settlement was established with simple mud buildings and most of them had four internal subdivisions. Numerous burials have been found, many with elaborate goods such as baskets, stone and bone tools, beads, bangles, pendants and occasionally animal sacrifices, with more goods left with burials of males. Ornaments of sea shell, limestone, turquoise, lapis lazuli, sandstone have been found, along with simple figurines of women and animals. Sea shells from far sea shore and lapis lazuli found far in Badakshan, Afghanistan shows good contact with those areas. A single ground stone axe was discovered in a burial, and several more were obtained from the surface. These ground stone axes are the earliest to come from a stratified context in the South Asia. Periods I, II and III are contemporaneous with another site called Kili Gul Mohammed.

In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh made the discovery that the people of the Indus Valley Civilization, from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of proto-dentistry. Later, in April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. According to the authors, their discoveries point to a tradition of proto-dentistry in the early farming cultures of that region. "Here we describe eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that dates from 7,500 to 9,000 years ago. These findings provide evidence for a long tradition of a type of proto-dentistry in an early farming culture."[5]

Mehrgarh Period II and Period III

Mehrgarh Period II 5500 BCE–4800 BCE and Merhgarh Period III 4800 BCE–3500 BCE were ceramic Neolithic (i.e., pottery was now in use) and later chalcolithic. Period II is at site MR4 and period III is at MR2.[2] Much evidence of manufacturing activity has been found and more advanced techniques were used. Glazed faience beads were produced and terracotta figurines became more detailed. Figurines of females were decorated with paint and had diverse hairstyles and ornaments. Two flexed burials were found in period II with a covering of red ochre on the body. The amount of burial goods decreased over time, becoming limited to ornaments and with more goods left with burials of females. The first button seals were produced from terracotta and bone and had geometric designs. Technologies included stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns and copper melting crucibles. There is further evidence of long-distance trade in period II: important as an indication of this is the discovery of several beads of lapis lazuli—originally from Badakshan. Mehrgarh Periods II and III are also contemporaneous with an expansion of the settled populations of the borderlands at the western edge of South Asia, including the establishment of settlements like Rana Ghundai, Sheri Khan Tarakai, Sarai Kala, Jalilpur, and Ghaligai.[2]

Mehrgarh period IV, V and VI

Period IV was 3500 to 3250 BCE. Period V from 3250 to 3000 BCE and period VI was around 3000 BCE.[7] The site containing Periods IV to VII is designated as MR1.[2]

Mehrgarh Period VII

Somewhere between 2600 BCE and 2000 BCE,[citation needed] the city seems to have been largely abandoned in favor of the new nearby settlement of Nausharo when the Indus Valley Civilisation was in its middle stages of development.

Mehrgarh Period VIII

The last period is found at the Sibri cemetry, about 8 KM from Mehrgarh.[2]

Artifacts

Human Figurines

The oldest ceramic figurines in South Asia were found at Mehrgarh. They occur in all phases of the settlement and were prevalent even before pottery appears. The earliest figurines are quite simple and do not show intricate features. However, they grow in sophistication with time, and by 4000 B.C., begin to show the characteristic hairstyles and prominent breasts. All the figurines upto this period were female. Male figurines appear only from period VII and gradually become more numerous. Many of the female figurines are holding babies, and were interpreted as depictions of "mother goddess".[8][9] However, due to some difficulties in conclusively identifying these figurines with "mother goddess", some scholars prefer using the term "female figurines with likely cultic significance".[10]

Pottery

Evidence of pottery begins from Period II. In period III, the finds becomes much more abundant as the potter's wheel is introduced, and they show more intricate designs and also animal motifs.[2] The characteristic female figurines appear from Period IV and the finds show more intricate designs and sophistication. Pipal leaf designs are used in decoration from Period VI.[11] Some sophisticated firing techniques were used from Period VI and VII and an area reserved for the pottery industry has been found at mound MRI. However, by Period VIII, the quality and intricacy of designs seems to have suffered due to mass production, and due to a growing interest in bronze and copper vessels.[7]

Metallurgy

Metal finds begin with a few copper items in Period IIB.[2][11]

Common variant spellings

- Mehrgarh is also spelled as Mehrgahr, Merhgarh or Merhgahr.

- Kachi plain is also spelled as Kacchi plain, Katchi plain.

See also

- Bolan Pass

- Indus Valley Civilization

- Nausharo

- Pirak

- Quetta

- Sheri Khan Tarakai

Notes

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh". Guide to Archaeology

- ^ a b c d e f g Sharif, M; Thapar, B. K. (1999). "Food-producing Communities in Pakistan and Northern India". In Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson. History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. pp. 128–137. ISBN 978-81-208-1407-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=GXzycd3dT9kC&pg=PA128. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. 1996. "Mehrgarh." Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press

- ^ Meadow, Richard H. (1996). David R. Harris. ed. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=zkteuesBwpQC&pg=PA393. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b Coppa, A. et al. 2006. "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population." Nature. Volume 440. 6 April 2006.

- ^ Kenoyer, J. Mark, and Kimberly Heuston. 2005. The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. 176 pages. ISBN 0195174224.

- ^ a b Maisels, Charles Keith. Early Civilizations of the Old World. Routledge. pp. 190-193.

- ^ Sarah M. Nelson (February 2007). Worlds of gender: the archaeology of women's lives around the globe. Rowman Altamira. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-7591-1084-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=ab1rF6tznkoC&pg=PA77. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Sharif, M; Thapar, B. K.. "Food-producing Communities in Pakistan and Northern India". History of civilizations of Central Asia. pp. 254-256. http://books.google.co.in/books?id=GXzycd3dT9kC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA254#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Upinder Singh. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. pp. 130–. http://books.google.com/books?id=H3lUIIYxWkEC&pg=PA130. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b Upinder Singh (1 September 2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=H3lUIIYxWkEC&pg=PA103. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

Further Reading

- Avari, Burjor, India: The Ancient Past: A history of the Indian sub-continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200, Routledge.

- Singh, Upinder, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century, Dorling Kindersley, 2008, ISBN 9788131711200.

- Lallanji Gopal, V. C. Srivastava, History of Agriculture in India, up to c. 1200 AD.

- Jarrige, J. F. (1979). "Excavations at Mehrgarh-Pakistan". In Johanna Engelberta Lohuizen-De Leeuw. South Asian archaeology 1975: papers from the third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, held in Paris. Brill. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-90-04-05996-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=H2GW1PTHQ1YC&pg=PA76. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Jarrige, Jean-Franois, Mehrgarh Neolithic.

- Jarrige, C, J. F. Jarrige, R. H. Meadow, G. Quivron, eds (1995/6), Mehrgarh Field Reports 1974-85: From Neolithic times to the Indus Civilization.

- Jarrige J. F., Lechevallier M., Les fouilles de Mehrgarh, Pakistan : problèmes chronologiques [Excavations at Mehrgarh, Pakistan: chronological problems] (French).

- Lechevallier M., L'Industrie lithique de Mehrgarh (Pakistan) [The Lithic industry of Mehrgarh (Pakistan)] (French).

- Gregory L. Possehl (2002). The Indus civilization: a contemporary perspective. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=pmAuAsi4ePIC&pg=PP1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (2000). God-apes and fossil men: paleoanthropology of South Asia. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11013-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=W6zQHNavWlsC&pg=PR4. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Bridget Allchin; Frank Raymond Allchin (1982). The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=r4s-YsP6vcIC&pg=PP1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Michael D. Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (2007). The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia: inter-disciplinary studies in archaeology, biological anthropology, linguistics and genetics. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=Qm9GfjNlnRwC&pg=PP1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Niharranjan Ray; Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (1 January 2000). "Pre-Harappan Neolithic-Chalcolothic Settlement at Mehrgarh, Baluchistan Pakistan". A sourcebook of Indian civilization. Orient Blackswan. pp. 560–. ISBN 978-81-250-1871-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=Zcyho16xzWEC&pg=PA560. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- J. G. Shaffer; B. K. Thapar, et al (2005). History of civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=6lPzhfNRZ9IC&pg=PA1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Jane McIntosh (2008). The ancient Indus Valley: new perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=1AJO2A-CbccC&pg=PP1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Lukacs, J. R., Dental Morphology and Odontometrics of Early Agriculturalists from Neolithic Mehrgarh, Pakistan.

- Santoni, Marielle, Sibri and the South Cemetery of Mehrgarh: Third Millennium Connections between the Northern Kachi Plain (Pakistan) and Central Asia.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A history of India. Routledge. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=TPVq3ykHyH4C&pg=PA21. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Jim G. Shaffer; Diane A Lichtenstein (1995). George Erdösy. ed. The Indo-Aryans of ancient South Asia: Language, material culture and ethnicity. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=A6ZRShEIFwMC&pg=PA130. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Steven Mithen (30 April 2006). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000-5000 BC. Harvard University Press. pp. 408–. ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=NVygmardAA4C&pg=PA408. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Barthelemy De Saizieu B., Le Cimetière néolithique de Mehrgarh (Balouchistan pakistanais) : apport de l'analyse factorielle [The Neolithic cemetery of Mehrgarh (Balochistan Pakistan): Contribution of a factor analysis] (French).

- Burton Stein (26 April 2010). "Ancient Days: The Pre-Formation of Indian Civilization". In David Arnold. A History of India. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=0K3GZfqCabsC&pg=PA39.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (February 2007). "Gender and Archaeology in South and Southwest Asia". In Sarah M. Nelson. Worlds of gender: the archaeology of women's lives around the globe. Rowman Altamira. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-7591-1084-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=ab1rF6tznkoC&pg=PA75. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan M.; Miller, Heather M. L. (1999). "Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India". In Vincent C. Pigott. The archaeometallurgy of the Asian old world. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-0-924171-34-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=AjUy9SA3vqcC&pg=PA123. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2002). Peter Neal Peregrine, Melvin Ember. ed. Encyclopedia of Prehistory: South and Southwest Asia. Springer. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-306-46262-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=C-TQpUtI-dgC&pg=PA153. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

External links

- India. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/285248/India/46801/The-early-prehistoric-period?anchor=ref484939

- Origins of agriculture. (2011). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/9647/agriculture

- Dr. Ahmad Hasan Dani, "History Through The Centuries", National Fund for Cultural Heritage

- Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, "Early Developments of Art, Symbol and Technology in the Indus Valley Tradition"

- "Stone age man used dentist drill" BBC News

- "Mehrgarh", Travel Web[dead link]

- "Mehrgarh, Pakistan: Discovery of a 9000-Year-Old Civilized Settlement", SEMP

- Indus and Mehrgarh archaeological mission: The Centre for Archaeological Research Indus Balochistan

Coordinates: 29°24′21″N 67°35′55″E / 29.40583°N 67.59861°E

Balochistan, Pakistan topics

Balochistan, Pakistan topicsHistory Government

and politicsProvincial Assembly · Chief Minister · Governor · Tumandar · Balochistan conflict · Hazara Democratic Party · Baloch nationalismCulture and

placesBaloch people · List of Baloch tribes · Language · Cuisine · Diaspora · Music · Brahui people · Brahui language · Hazara peopleGeography Education Sport Categories:- History of South Asia

- Archaeological sites in Pakistan

- History of Balochistan

- Neolithic settlements

- Pre-Harappan sites

- Pre-Islamic heritage of Pakistan

- Former populated places in Pakistan

- Quetta District

- Populated places established in the 7th millennium BC

- History of India

- Europe

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.