- Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction

-

Pakistan Nuclear program start date January 20, 1972 First nuclear weapon test May 28, 1998 First fusion weapon test Unknown Last nuclear test May 30, 1998 Largest yield test 25-36 kt in 1998

(PAEC claim)[1]Total tests 6 detonations Peak stockpile 100-110 warheads

(2011 estimate)[2]Current stockpile 100-110 warheads[2] Maximum missile range 2,500 km (Shaheen-II)[3] NPT signatory No Weapons of

mass destruction

By type Biological, Chemical, Nuclear, Radiological By country Proliferation Biological, Chemical, Nuclear, Missiles Treaties List of treaties  Book ·

Book ·  Category

CategoryNuclear weapons

History

Warfare

Arms race

Design

Testing

Effects

Delivery

Espionage

Proliferation

Arsenals

Terrorism

Anti-nuclear oppositionNuclear-armed states United States · Russia

United Kingdom · France

China · India · Israel

Pakistan · North Korea

South Africa (former)Pakistan began focusing on nuclear weapons development in January 1972 under the leadership of Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who delegated the program to the Chairman of PAEC Munir Ahmad Khan. In 1976, Abdul Qadeer Khan also joined the nuclear weapons program, and, with Zahid Ali Akbar, headed the Kahuta Project, while the rest of the program being run in PAEC and comprising over twenty laboratories and projects was headed by Munir Ahmad Khan.[4] This program would reach fruition under President General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, then-Chief of Army Staff. Pakistan's nuclear weapons development was in response to neighboring India's development of nuclear weapons. Bhutto called a meeting of senior academic scientists and engineers on 20 January 1972, in Multan, which came to known as "Multan meeting".[5] Bhutto was the main architect of this programme and it was here that Bhutto orchestrated nuclear weapons programme and rallied Pakistan's academic scientists to build the atomic bomb for national survival.[6] At the Multan meeting, Bhutto also appointed nuclear engineer, Munir Ahmad Khan, as chairman of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC), who, until then, had been working as Director at the Nuclear Power and Reactor Division of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), in Vienna, Austria. In December 1972, Abdus Salam led the establishment of Theoretical Physics Group (TPG) as he called scientists working at ICTP to report to Munir Ahmad Khan. This marked the beginning of Pakistan's pursuit of nuclear detterence capability. Following India's surprise nuclear test, codenamed Smiling Buddha in 1974, the first confirmed nuclear test by a nation outside the permanent five members of the United Nations Security Council, the goal to develop nuclear weapons received considerable impetus.[5]

Finally, on 28 May 1998, a few weeks after India's second nuclear test (Operation Shakti), Pakistan detonated five nuclear devices in the Chagai Hills in the Chagai district, Balochistan. This operation was named Chagai-I by Pakistan, the underground iron-steel tunnel having been long-constructed by provincial Martial Law Administrator General Rahimuddin Khan during the 1980s. The last test of Pakistan was conducted at the sandy Kharan Desert under a codename Chagai-II, also in Balochistan, on May 30, 1998. Pakistan's fissile material production takes place at Nilore, Kahuta, and Khushab/Jauharabad, where weapons-grade plutonium is made by the scientists. Pakistan thus became the 7th country in the world to successfully develop and test nuclear weapons.[7]

Contents

History of Pakistan's nuclear weapons program

See also: Project-706Initial refusal to start a nuclear programme

Pakistan's nuclear energy programme was started in 1956, following the establishment of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) under its first chairman dr. Nazir Ahmed, by the Government of Prime minister, Huseyn Suhravardy. In 1958, General Ayub Khan, Commander-in-Chief of Pakistan Army, seized control and imposed martial law in the country after the success of the coup d'état against the Government of Iskander Mirza. Since then, Ayub Khan and his military government had repeatedly vetoed proposals made by PAEC to expand the nuclear research facilities and laboratories based on the economic grounds. On December 11 of 1965, months after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, President Ayub Khan had a brief meeting with Pakistani IAEA nuclear engineer Munir Ahmad Khan at the Dorchester Hotel in London. This meeting was arranged by the then Foreign minister of Pakistan Mr. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.[8][9] During the meeting, Munir Ahmad Khan told clearly to President Ayub Khan that Pakistan must acquire the necessary facilities that would give the country a nuclear deterrent capability, which were available free of safeguards and at an affordable cost.[9] Munir Ahmad Khan also pointed out to Ayub Khan that there were no restrictions on nuclear technology, that it was freely available, and that India and Israel were moving forward in deploying it.[9]

When asked about the economics of such programme, Munir Ahmad Khan estimated the cost of nuclear technology at that time. Because things were less expensive, the then costs were not more than $150 million. President Ayub Khan listened to him very patiently, but at the end of the meeting, Ayub Khan remained unconvinced.[9] Ayub Khan clearly refused Munir Ahmad Khan's offer and said that Pakistan was too poor to spend that much money. Moreover, President Ayub Khan mentioned that if Pakistan ever needed the bomb, Pakistan could somehow acquire it off the shelf.[9] Although Pakistan began the development of nuclear weapons in 1972, Pakistan responded to India's 1974 nuclear test (see Smiling Buddha) with a number of proposals to prevent a nuclear competition in South Asia.[10] On many different occasions, India rejected the offer.[10]

Nuclear energy program

Main article: Nuclear energy in PakistanPakistan's nuclear energy programme was established and started in 1956 following the establishment of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). Pakistan became a participant in U.S President Eisenhower's "Atoms for Peace Program." PAEC's first chairman was Dr. Nazir Ahmad.[11] In 1961, the PAEC set up a Mineral Center at Lahore and a similar multidisciplinary Center was set up in Dhaka, in the then East Pakistan. With these two centers, the basic research work started.[11]

The first thing that was to be undertaken was the search for Uranium. This continued for about 3 years from 1960 to 1963. Uranium deposits were discovered in the Dera Ghazi Khan district and the first-ever national award was given to the PAEC. Mining of uranium began in the same year. Dr. Abdus Salam and Dr. Ishrat Hussain Usmani also sent a large number of scientists to pursue doctorate degrees in the field of Nuclear Technology and Nuclear reactor technology. In December 1965, then-Foreign Minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto visited Vienna where he met IAEA nuclear engineer, Munir Ahmad Khan. At a Vienna meeting on December, Munir A. Khan informed Bhutto about the status of Indian nuclear program.[11]

The next landmark under [Dr. Abdus Salam] was the establishment of PINSTECH – Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, at Nilore near Islamabad. The principal facility there was a 5MWe research reactor, commissioned in 1965 and consisting of the PARR-I, which was upgraded to 10 MWe by Nuclear Engineering Division under Munir Ahmad Khan in 1990.[12] A second Atomic Research Reactor, known as PARR-II, was a Pool-type, light-water, 27-30 kWe, training reactor that went critical in 1989 under Munir Ahmad Khan.[13] The PARR-II reactor was built and provided by PAEC under the IAEA safeguards as IAEA had funded this mega project.[13] The PARR-I reactor was, under the agreement signed by PAEC and ANL, provided by the United States Government in 1965, and scientists from PAEC and ANL had led the construction.[12] Canada build Pakistan's first civil-purpose nuclear power plant.[11] The Ayub Khan Military Government made then-Science Advisors to the Government Abdus Salam as the head of the IAEA delegation. Abdus Salam began lobbying for commercial nuclear power plants, and tirelessly advocated for nuclear power in Pakistan.[14] In 1965, Salam's efforts finally paid off, and a Canadian firm signed a deal to provide 137MWe CANDU reactor in Paradise Point, Karachi. The construction began in 1966 as PAEC its general contractor as GE Canada provided nuclear materials and financial assistance. Its project director was Parvez Butt, a nuclear engineer, and its construction completed in 1972. Known as KANUPP-I, it was inaugurated by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as President, and began its operations in November 1972. Currently, Pakistan Government is planning to build another 400MWe commercial nuclear power plant. Having known as KANUPP-II, the PAEC completed its feasibility studies in 2009. However, the work is put on hold since 2009.

The PAEC in 1970 began work on a pilot-scale plant at Dera Ghazi Khan for the concentration of uranium ores. The plant had a capacity of 10,000 pounds a day.[15] In 1989, Munir Ahmad Khan signed a Nuclear cooperation deal and, since 2000, Pakistan is developing two more nuclear power plants with the an agreement signed with China. Both these plants are of 300MW capacity and are being built at Chashma city of Punjab Province called CHASNUPP-I, began producing electricity in 2000, and CHASNUPP-II, began its operation in fall of 2011. In 2011, the Board of Governors of International Atomic Energy Agency gave approval of Sino-Pak Nuclear Deal, allowing Pakistan legally to built 300MWe CHASNUPP-III and CHASNUPP-VI reactors.[16]

Development of nuclear weapons

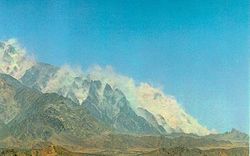

On May 28th of 1998, the mountain is seen raised above as the chain reaction built up. This operation was named as Chagai-I.

On May 28th of 1998, the mountain is seen raised above as the chain reaction built up. This operation was named as Chagai-I.

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 led to Pakistan losing roughly 56,000 square miles (150,000 km2) of territory as well as losing millions of its citizens to the newly created state of Bangladesh.[17] It was a psychological setback for Pakistanis; Pakistan had lost its geo-political, strategic, and economic influence in South-Asia.[17] Furthermore, Pakistan had failed to gather any moral support from its key allies, the United States and the People's Republic of China.[18] Isolated internationally, and twenty-four years after the partition, the Two-Nation Theory was failed, and Pakistan seemed to be in great mortal danger, and quite obviously could rely on no one but itself.[18] At United Nations Security Council meeting, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto drew comparisons with the Treaty of Versailles which Germany was forced to sign in 1919. There, Bhutto vowed never to allow a repeat. Prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was "obsessed" with India's nuclear program,[19] that is why Bhutto immediately came up with the idea of obtaining nuclear weapons to prevent Pakistan from signing another 'Treaty of Versailles' as it did in 1971. At the Multan meeting on January 20, 1972, Bhutto stated, "What Raziuddin Siddiqui, a Pakistani, contributed for the United States during the Manhattan Project, could also be done by scientists in Pakistan, for their own people."[8] Raziuddin Siddiqui was a Pakistani theoretical physicist who, in the early 1940s, worked on both the British nuclear program and the US nuclear program.[20] Although a few Pakistanis worked on the Manhattan Project who were also willing to return and do the same for their native Pakistan, Prime Minister Bhutto still needed to recruit and bring in other Pakistani nuclear scientists and engineers who never worked in the United States. This is where Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, a German educated metallurgical engineer, came into the picture. Some of the initial funding came from oil-rich Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia.

In later years, some funding for the continuation of the nuclear development programme came from the large British Pakistani population. In December 1972, Science Advisor to the President, Dr. Abdus Salam had called theoretical physicists from ICTP to report of Munir Ahmad Khan, Chairman of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission. This marked the beginning of the "Theoretical Physics Group" (TPG).[21] Later, Pakistani theoretical physicists at Institute of Physics of Quaid-e-Azam University also joined the TPG headed by Salam.[22] The TPG, in PAEC, was assigned to took research in the development of nuclear weapon devices, and it had directly reported to Abdus Salam.[22] Professor Salam also had done the groundbreaking work of the "Theoretical Physics Group", which was initially headed by Salam until in 1974 when he left the country in protest.[22] On other side, Munir Ahmad Khan began to work on ingenious development of nuclear fuel cycle and the weapons programme. Munir Ahmad Khan, with his life long friend Abdus Salam, had done a groundbreaking work in the nuclear development, and after Salam's departure from Pakistan, scientists and engineers who were researching under Salam, began to report to directly to Munir Ahmad Khan.[23] In 1974, Munir Ahmad Khan, days after Operation Smiling Buddha, launched the extensive plutonium reprocessing and uranium enrichment programme, and the research facilities were expanded throughout the country.[24]

In 1965,[25] amidst skirmishes that led up to the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 Zulfikar Ali Bhutto announced:

“ If India builds the bomb, we will eat grass and leaves for a thousand years, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own. The Christians have the bomb, the Jews have the bomb and now the Hindus have the bomb. Why not the Muslims too have the bomb?[26][27] ” In 1983, Khan was convicted by a Dutch court in absentia for stealing the blueprints, though the conviction was overturned on a legal technicality.[28] A.Q. Khan then established a proliferation network through Dubai to smuggle URENCO nuclear technology to Khan Research Laboratories. He then established Pakistan's gas-centrifuge program based on the URENCO's Zippe-type centrifuge.[28][29][30][31][32]

Through the late 1970s, Pakistan's program acquired sensitive uranium enrichment technology and expertise. The 1975 arrival of Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan considerably advanced these efforts. Dr. Khan is a German-trained metallurgist who brought with him knowledge of gas centrifuge technologies that he had through his position at the classified URENCO uranium enrichment plant in the Netherlands. He was put in charge of building, equipping and operating Pakistan's Kahuta facility, which was established in 1976. Under Khan's direction, Pakistan employed an extensive clandestine network in order to obtain the necessary materials and technology for its developing uranium enrichment capabilities.[33]

A new directorate, known as Directorate of Technical Development (DTD) under Dr. Zaman Sheikh and Hafeez Qureshi, was established in March 1974 by Munir Ahmad Khan. The DTD was tasked to manufacture chemical explosive lenses, trigger mechanism, and tempers used in atomic weapon. The DTD was later charged with testing Pakistan's first implosion design in 1978, which was later improved and tested on 11 March 1983 when PAEC carried out Pakistan's first successful cold test of a nuclear device, codename Kirana-I. Between 1983 and 1990, PAEC carried out 24 more cold tests of various nuclear weapon designs. DTD had also manufactured a miniaturized weapon design by 1987 that could be delivered by all Pakistan Air Force fighter aircraft.[34]

Also, Dr. Ishrat Hussain Usmani’s contribution to the nuclear energy programme, is also fundamental to the development of atomic energy for civilian purposes as he, with efforts led by Salam, established PINSTECH, that subsequently developed into Pakistan’s premier nuclear research institution.[22] In addition to sending hundreds of young Pakistanis abroad for training, he laid the foundations of the Muslim world’s first nuclear power reactor KANUPP, which was inaugurated by Munir Ahmad Khan in 1972. Thus, Usmani laid solid groundwork for the civilian nuclear programme[35] Scientists and engineers under Munir Ahmad Khan developed the nuclear capability for Pakistan within early 1980s, and under his leadership the PAEC had carried a cold test of nuclear device at Kirana Hills, evidently made from non-weaponized plutonium. Former chairman of the PAEC, Munir Ahmad Khan was credited as one of the pioneers of Pakistan's atomic bomb by a recent study from the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), London's dossier on Pakistan's nuclear weapons program.[6]

Policy

Pakistan acceded to the Geneva Protocol on 15 April 1960. As for its Biological warfare capability, Pakistan is not widely suspected of either producing biological weapons or having an offensive biological programme.[36] However, the country is reported to have well developed bio-technological facilities and laboratories, devoted entirely to the medical research and applied health sciences.[36] In 1972, Pakistan signed and ratified the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) in 1974.[36] Since then Pakistan has been a vocal and staunch supporter for the success of the BTWC. During the various BTWC Review Conferences, Pakistan's representatives have urged more robust participation from state signatories, invited new states to join the treaty, and, as part of the non-aligned group of countries, have made the case for guarantees for states' rights to engage in peaceful exchanges of biological and toxin materials for purposes of scientific research.[36]

Pakistan is not known to have an offensive chemical weapons programme, and in 1993 Pakistan signed and ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and has committed itself to refrain from developing, manufacturing, stockpiling, or using chemical weapons.[37]

In 1999, Prime Ministers Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan and Atal Bihari Vajpayee of India signed the Lahore Declaration, agreeing to a bilateral moratorium on nuclear testing. This initiative was taken after an year past of both countries publicly tested nuclear devices (See Pokhran-II, Chagai-I and II). However, Pakistan is not a party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty(NPT) and, consequently, not bound by any of its provisions.

Since early 1980s, Pakistan's nuclear proliferation activities have not been without controversy. However, since the arrest of Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Government has taken concrete steps to ensure that Nuclear proliferation is not repeated and have assured the IAEA about the transparency of Pakistan's upcoming Chashma Nuclear Power Complex series of Nuclear Power Plants. In November 2006, The International Atomic Energy Agency Board of Governors approved an agreement with the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission to apply safeguards to new nuclear power plants to be built in the country with Chinese assistance.[38]

Protection

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton informed that Pakistan has dispersed its nuclear weapons throughout the country, increasing the security so that they could not fall into terrorist hands. Her comments came as new satellite images released by the ISIS suggested Pakistan is increasing its capacity to produce plutonium, a fuel for atomic bombs. The institute has also claimed that Pakistan has built two more nuclear reactors at Khoshab increasing the number of plutonium producing reactors to three.[39]

In May 2009, during the anniversary of Pakistan's first nuclear weapons test, former Prime Minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif claimed that Pakistan’s nuclear security is the strongest in the world.[40] According to Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, Pakistan's nuclear safety program and nuclear security program is the strongest program in the world and there is no such capability in any other country for radical elements to steal or possess nuclear weapons.[41]

Modernisation and expansion

Pakistan is increasing its capacity to produce plutonium at its Khushab nuclear facility, a Washington-based science think tank has reported.[42] Estimated Pakistani nuclear weapons is probably in the neighborhood of more than 200 by the end of 2009. “The sixth Pakistani nuclear test (May 30, 1998) at Kharan was a successful test of a sophisticated, compact, but powerful bomb designed to be carried by missiles. The Pakistanis are believed to be spiking their plutonium based nuclear weapons with tritium. Only a few grams of tritium can result in an increase of the explosive yield by 300% to 400%.”[43] Citing new satellite images of the facility, the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) said the imagery suggests construction of the second Khushab reactor is “likely finished and that the roof beams are being placed on top of the third Khushab reactor hall”.[44]

Infrastructure

Uranium infrastructure

The Uranium infrastructure is based, primarily, on highly-enriched uranium (HEU),[1] which is produced at the Khan Research Laboratories at Kahuta, a Zippe centrifuge-based uranium-enrichment facility. The Kahuta facility has been in use since the early 1980s. By the early 1990s, Kahuta had an estimated 3,000 centrifuges in operation, and Pakistan has continued its pursuit of expanded uranium-enrichment capabilities.

The uranium programme was started immediately after India's surprise nuclear test conducted at Indian Army base, the Pokhran Test Range, in 1974, under codename Smiling Buddha. Smiling Buddha was seen as a final threat to Pakistan's existence.[18] In response, Munir Ahmad Khan launched the uranium enrichment program, known as Project-706, under nuclear engineer Sultan Bashiruddin Mehmood. Mehmood theoretically analyzed gaseous diffusion, gas centrifuge, jet nozzle and laser enrichment processes, and selected the centrifuge program. Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, a metallurgical engineer, joined this program in 1976, but became highly dissatisfied with PAEC's approach to ingeniously developing of this program with no foreign assistance required. In spring of 1976, Abdul Qadeer Khan took over the program and founded Engineering Research Laboratories (ERL), starting from centrifuge designs he stole from his employer URENCO, the Dutch firm where he had worked as a senior scientist. After the program was successfully developed, Khan sent the designs of these centrifuges to Iran, Iraq, Libya and North-Korea to aid their nuclear ambitious.

Plutonium infrastructure

As oppose to uranium enrichment, the plutonium programme is ingeniously and locally developed and culminated under watchful eyes of PAEC Chairman Munir Ahmad Khan. In the end of 1970s, Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission began to pursue Plutonium production capabilities. Consequently Pakistan built the 40-50 MW (megawatt, thermal) Khushab Research Reactor at Joharabad, and in April 1998, Pakistan announced that the nuclear reactor was operational. The Khushab reactor project was initiated in 1986 by PAEC Chairman Munir Ahmad Khan, who informed the world that the reactor was totally indigenous, i.e. that it was designed and built by Pakistani scientists and engineers. Various Pakistani industries contributed in 82% of the reactor's construction. The Project-Director for this project was Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood. According to public statements made by the U.S. Government officials, this heavy-water reactor can produce up to 8 to 10 kg of plutonium per year with increase in the production by the development of newer facilities,[45] sufficient for at least one nuclear weapon.[46] The reactor could also produce tritium if it were loaded with lithium-6, although this is unnecessary for the purposes of nuclear weapons, because modern nuclear weapon designs use 6Li directly. According to J. Cirincione of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Khushab's Plutonium production capacity has allowed Pakistan to develop lighter nuclear warheads that would be easier to deliver to any place in the range of the ballistic missiles.[citation needed]

The Plutonium separation takes place at the New Laboratories, a reprocessing plant, which was completed by 1981 by PAEC and is next to the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology (PINSTECH) near Islamabad, which is not subject to IAEA inspections and safeguards.

In late 2006, the Institute for Science and International Security released intelligence reports and imagery showing the construction of a new plutonium reactor at the Khushab nuclear site. The reactor is deemed to be large enough to produce enough plutonium to facilitate the creation of as many as "40 to 50 nuclear weapons a year."[47][48][49] The New York Times carried the story with the insight that this would be Pakistan's third plutonium reactor,[50] signaling a shift to dual-stream development, with Plutonium-based devices supplementing the nation's existing HEU stream to atomic warheads.

Stockpile

Estimates of Pakistan's stockpile of nuclear warheads vary. The most recent analysis, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 2010, estimates that Pakistan has 70-90 nuclear warheads.[51] In 2001, the U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimated that Pakistan had built 24–48 HEU-based nuclear warheads with HEU reserves for 30-52 additional warheads.[52][53] In 2003, the U.S. Navy Center for Contemporary Conflict estimated that Pakistan possessed between 35 and 95 nuclear warheads, with a median of 60.[54] In 2003, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace estimated a stockpile of approximately 50 weapons. By contrast, in 2000, U.S. military and intelligence sources estimated that Pakistan's nuclear arsenal may be as large as 100 warheads.[55]

The actual size of Pakistan's nuclear stockpile is hard for experts to gauge owing to the extreme secrecy which surrounds the program in Pakistan. However, in 2007, retired Pakistan Army's Brigadier-General Feroz Khan, previously second in command at the Strategic Arms Division of Pakistans' Military told a Pakistani newspaper that Pakistan had "about 80 to 120 genuine warheads."[56][57]

Pakistan tested plutonium capability in the sixth nuclear test, codename Chagai-II, on 30 May 1998 at Kharan Desert. In this test the most compact and sophisticated design, made to be carried by small delivery vehicles such as MIRV and cruise missiles, was tested.[citation needed]

The critical mass of a bare mass sphere of 90% enriched uranium-235 is 52 kg. Correspondingly, the critical mass of a bare mass sphere of plutonium-239 is 8–10 kg. The bomb that destroyed Hiroshima used 60 kg of U-235 while the Nagasaki Pu bomb used only 6 kg of Pu-239. Since all Pakistani bomb designs are implosion-type weapons, they will typically use between 15–25 kg of U-235 for their cores. Reducing the amount of U-235 in cores from 60 kg in gun-type devices to 25 kg in implosion devices is only possible by using good neutron reflector/tamper material such as beryllium metal, which increases the weight of the bomb. And the uranium, like plutonium, is only usable in the core of a bomb in metallic form.

However, only 2–4 kg of plutonium is needed for the same device that would need 20–25 kg of U-235. Additionally, a few grams of tritium (a by-product of plutonium production reactors and thermonuclear fuel) can increase the overall yield of the bombs by a factor of three to four. “The sixth Pakistan nuclear test, codename Chagai-II, (May 30, 1998) at Kharan Desert was a successful test of a sophisticated, compact, but powerful bomb designed to be carried by missiles. The Pakistanis are believed to be spiking their plutonium based nuclear weapons with tritium. Only a few grams of tritium can result in an increase of the explosive yield by 300% to 400%.”[43]

A whole range and variety of weapons using Pu-239 can be easily built, both for aircraft delivery and especially for missiles (in which U-235 cannot be used). So if Pakistan wants to be a nuclear power with an operational deterrent capability, both first and second strike, based on assured strike platforms like ballistic and cruise missiles (unlike aircraft), the only solution is with plutonium, which has been the first choice of every country that built a nuclear arsenal.

As for Pakistan's plutonium capability, it has always been there, from the early 1970s onwards. However, there were only two logistic problems faced by PAEC. One was that Pakistan did not want to be an irresponsible state and the PAEC did not divert spent fuel from the safeguarded KANUPP for reprocessing at the New Labs. This was enough to build a whole arsenal of nuclear weapons straight away. The PAEC built its own plutonium and tritium production reactor at Khushab, known as Khushab-I reactor, beginning in 1985. The second one was allocation of resources.

Ultra-centrifugation for obtaining U-235 cannot be done simply by putting natural uranium through the centrifuges. It requires the complete mastery over the front end of the nuclear fuel cycle, beginning at uranium mining and refining, production of uranium ore or yellow cake, conversion of ore into uranium dioxide UO2 (which is used to make nuclear fuel for natural uranium reactors like Khushab and KANUPP), conversion of UO2 into uranium tetrafluoride UF4 and then into the feedstock for enrichment (UF6).

The complete mastery of fluorine chemistry and production of highly toxic and corrosive hydrofluoric acid and other fluorine compounds is required. The UF6 is pumped into the centrifuges for enrichment. The process is then repeated in reverse until UF4 is produced, leading to the production of uranium metal, the form in which U-235 is used in a bomb.

It is estimated that there are approximately 10,000-20,000 centrifuges in Kahuta. This means that with P2 machines, they would be producing between 75–100 kg of HEU since 1986, when full production of weapons-grade HEU began. Also the production of HEU was voluntarily capped by Pakistan between 1991 and 1997, and the five nuclear tests of 28 May 1998 also consumed HEU. So it is safe to assume that between 1986 and 2005 (prior to the 2005 earthquake), KRL produced 1500 kg of HEU. Accounting for losses in the production of weapons, it can be assumed that each weapon would need 20 kg of HEU; sufficient for 75 bombs as in 2005.

Pakistan's first nuclear tests were made in May 1998, when six warheads were tested under codename Chagai-I and Chagai-II. It is reported that the yields from these tests were 12 kt, 30 to 36 kt and four low-yield (below 1 kt) tests. From these tests Pakistan can be estimated to have developed operational warheads of 20 to 25 kt and 150 kt in the shape of low weight compact designs and may have 300–500 kt[58] large-size warheads. The low-yield weapons are probably in nuclear bombs carried on fighter-bombers such as the Dassault Mirage III and fitted to Pakistan's short-range ballistic missiles, while the higher-yield warheads are probably fitted to the Shaheen series and Ghauri series ballistic missiles.[58]

Second strike capability

According to a US congressional report, Pakistan has addressed issues of survivability in a possible nuclear conflict through second strike capability. Pakistan has been dealing with efforts to develop new weapons and at the same time, have a strategy for surviving a nuclear war. Pakistan has built hard and deeply buried storage and launch facilities to retain a second strike capability in a nuclear war.[59]

It was confirmed that Pakistan has built Soviet-style road-mobile missiles, state-of-the-art air defences around strategic sites, and other concealment measures. In 1998, Pakistan had 'at least six secret locations' and since then it is believed Pakistan may have many more such secret sites. In 2008, the United States admitted that it did not know where all of Pakistan’s nuclear sites are located. Pakistani defence officials have continued to rebuff and deflect American requests for more details about the location and security of the country’s nuclear sites.[60]

MIRV capability

Pakistani engineers are also said to be in the advance stages of developing MIRV technology for its missiles. This would allow the military to fit several warheads on the same ballistic missile and then launch them at separate targets.[61]

Foreign assistance

Historically, China is alleged to have played a major role in the establishment of Pakistan's nuclear weapons development infrastructure, especially, when increasingly stringent export controls in the western countries made it difficult for Pakistan to acquire nuclear materials and technology from elsewhere. Additionally, Pakistani officials have supposedly been present to observe at least one Chinese nuclear test. In a recent revelation by a high-ranking former U.S. official, it was disclosed that China had allegedly transferred nuclear technology to Pakistan and conducting Proxy Test for it in 1980.[62] According to a 2001 Department of Defense report, China has supplied Pakistan with nuclear materials and has provided critical technical assistance in the construction of Pakistan's nuclear weapons development facilities, in violation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, of which China is a signatory.[63][64]

In 1986, Pakistan and China signed a civilian nuclear technology agreement in which China would supply Pakistan a civil-purpose nuclear technology. A grand ceremony was held in Beijing where Pakistan's then Foreign Minister Sahibzada Yaqub Khan signed on behalf of Pakistan in the presence of Munir Ahmad Khan and Chinese Prime Minister. Therefore, in 1989, Pakistan reached agreement with China for the supply of a 300MW CHASHNUPP-1 nuclear power plant.

In February, 1990, President François Mitterrand of France visited Pakistan and announced that France had agreed to supply a 900 MWe nuclear power reactor to Pakistan. However, after the Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto was dismissed in August, 1990, the French nuclear power plant deal went into cold storage and the agreement could not be implemented due to financial constraints and the Pakistani government's apathy. Also in February 1990, Soviet Ambassador to Pakistan, V.P. Yakunin, said that the USSR was considering a request from Pakistan for the supply of a nuclear power plant. The Soviet and French civilian nuclear power plant was on its way during 1990s. However, Bob Oakley, the U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan, expressed U.S. displeasure at the recent agreement made between France and Pakistan for the sale of a nuclear power plant.[65] After the U.S. concerns the civilian-nuclear technology agreements were cancelled by France and Soviet Union.

Doctrine

Pakistan's motive for pursuing a nuclear weapons development program is never to allow another invasion of Pakistan. President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq summed it up in 1987 when he stated to Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi: "If your forces cross our borders by an inch, we are going to annihilate your cities".[33][66]

Pakistan has not signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). According to the U.S. Defense Department report cited above, "Pakistan remains steadfast in its refusal to sign the NPT, stating that it would do so only after India joined the Treaty. Pakistan has responded to the report by stating that the United States itself has not ratified the CTBT. Consequently, not all of Pakistan's nuclear facilities are under IAEA safeguards. Pakistani officials have stated that signature of the CTBT is in Pakistan's best interest, but that Pakistan will do so only after developing a domestic consensus on the issue, and have disavowed any connection with India's decision."

The organization authorized to make decisions about Pakistan's nuclear posturing is the NCA. Here is a link showing NCA of Pakistan.[67] It was established in February 2000. The NCA is composed of two committees that advise the present President of Pakistan, on the development and deployment of nuclear weapons; it is also responsible for war-time command and control. In 2001, Pakistan further consolidated its nuclear weapons infrastructure by placing the Khan Research Laboratories and the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission under the control of one Nuclear Defense Complex. In November 2009, Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari announced that he will be replaced by Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani as the chairman of NCA.[68]

U.S. assistance

From the end of 2001 the United States has provided material assistance to aid Pakistan in guarding its nuclear material, warheads and laboratories. The cost of the program has been almost $100 million. Specifically the USA has provided helicopters, night-vision goggles and nuclear detection equipment.[69]

Pakistan turned down the offer of Permissive Action Link (PAL) technology, a sophisticated "weapon release" program which initiates use via specific checks and balances, possibly because it feared the secret implanting of "dead switches". But Pakistan is since believed to have developed and implemented its own version of PAL and U.S. military officials have stated they believe Pakistan's nuclear weaponry to be well secured.[70][71]

Security concerns of the United States

Since 2004 the United States government has reportedly been concerned about the safety of Pakistani nuclear facilities and weapons. Press reports have suggested that the United States has contingency plans to send in special forces to help "secure the Pakistani nuclear arsenal".[72][73] Lisa Curtis of The Heritage Foundation giving testimony before the United States House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade concluded that "preventing Pakistan's nuclear weapons and technology from falling into the hands of terrorists should be a top priority for the U.S."[74] However Pakistan's government has ridiculed claims that the weapons are not secure.[72]

A report published by The Times in early 2010 states that the U.S. is training an elite unit to recover Pakistani nuclear weapons or materials should they be seized by militants, possibly from within the Pakistani nuclear security organization. This was done in the context of growing Anti-Americanism in the Pakistani Armed Forces, multiple attacks on sensitive installations over the previous 2 years and rising tensions. According to former U.S. intelligence official Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, U.S. concerns are justified because militants have struck at several Pakistani military facilities and bases since 2007. According to this report, the United States does not know the locations of all Pakistani nuclear sites and has been denied access to most of them.[75] However, during a visit to Pakistan in January 2010, the U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates denied that the United States had plans to take over Pakistan's nuclear weapons.[76]

A study by Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University titled 'Securing the Bomb 2010', found that Pakistan's stockpile "faces a greater threat from Islamic extremists seeking nuclear weapons than any other nuclear stockpile on earth".[77]

According to Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a former investigator with the CIA and the US department of energy there is "a greater possibility of a nuclear meltdown in Pakistan than anywhere else in the world. The region has more violent extremists than any other, the country is unstable, and its arsenal of nuclear weapons is expanding."[78]

Nuclear weapons expert David Albright author of 'Peddling Peril' has also expressed concerns that Pakistan's stockpile may not be secure despite assurances by both Pakistan and U.S. government. He stated Pakistan "has had many leaks from its program of classified information and sensitive nuclear equipment, and so you have to worry that it could be acquired in Pakistan,"[79]

A 2010 study by the Congressional Research Service titled 'Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons: Proliferation and Security Issues' noted that even though Pakistan had taken several steps to enhance Nuclear security in recent years 'Instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question.'[80]

In April 2011, IAEA's deputy director general Denis Flory declared Pakistan's nuclear programme safe and secure.[81][82] According to the IAEA, Pakistan is currently contributing more than $1.16 million in IAEA's Nuclear Security Fund, making Pakistan as 10th largest contributor.[83]

National Security Council

- National Security Council

- National Command Authority

- Ministry of Defence

- Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (JCSC)

- Strategic Planning Division (SPD)

Weapons development agencies

National Engineering & Scientific Commission (NESCOM)

- National Development Complex (NDC), Islamabad

- Project Management Organization (PMO), Khanpur

- Air Weapon Complex (AWC), Hasanabdal

- Maritime Technologies Complex (MTC), Karachi

Ministry of Defense Production

- Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF), Wah

- Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC), Kamra

- Defense Science and Technology Organization (DESTO), Chattar

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC)

- Directorate of Technical Development

- Directorate of Technical Equipment

- Directorate of Technical Procurement

- Directorate of Science & Engineering Services

- Institute of Nuclear Power, Islamabad

- Pakistan Institute of Science & Technology (PINSTECH)

- New Laboratories, Rawalpindi

- Pilot Reprocessing Plant

- PARR-1 and PARR-2 Nuclear Research Reactors

- Center for Nuclear Studies (CNS), Islamabad

- Computer Training Center (CTC), Islamabad

- Nuclear Track Detection Center (Solid State Nuclear Track Detection Center)

- Khushab Reactor, Khushab

- Atomic Energy Minerals Centre, Lahore

- Hard Rock Division, Peshawar

- Mineral Sands Program, Karachi

- Baghalchur Uranium Mine, Baghalchur

- Dera Ghazi Khan Uranium Mine, Dera Ghazi Khan

- Issa Khel/Kubul Kel Uranium Mines and Mills, Mianwali

- Multan Heavy Water Production Facility, Multan, Punjab

- Uranium Conversion Facility, Islamabad

- Golra Ultracentrifuge Plant, Golra

- Sihala Ultracentrifuge Plant, Sihala

- Directorate of Quality Assurance,Islamabad

- New Labs Nilore,Islamabad

Space and Upper Atmospheric Research Commission (SUPARCO)

- Aerospace Institute, Islamabad.

- Computer Center, Karachi.

- Control System Laboratories.

- Sonmian Satellite Launch Center, Sonmiani Beach.

- Instrumentation Laboratories, Karachi.

- Material Research Division.

- Quality Control and Assurance Unit.

- Rocket Bodies Manufacturing Unit.

- Solid Composite Propellant Unit.

- Liquid Composite Propellant Unit

- Space and Atmospheric Research Center (space Center), Karachi

- Static Test Unit, Karachi

- Tilla Satellite Launch Center, Tilla, Punjab

Precision Engineering Complex (PEC)

Ministry of Industries & Production

- State Engineering Corporation (SEC)

- Heavy Mechanical Complex Ltd. (HMC)

- Pakistan Steel Mills Limited, Karachi.

Delivery systems

Land systems

As of 2011, Pakistan possesses a wide variety of thermonuclear MIRV-equipped medium range ballistic missiles with ranges up to 2500 km. Pakistan is also believed to be developing tactical nuclear weapons for use on the battlefield with ranges up to 60 km such as the Nasr missile. Pakistan also possesses nuclear tipped Babur cruise missiles with ranges up to 700 km. With further funding and R&D, Pakistan can also develop Intermediate-range ballistic missiles such as the Shaheen-III which will enable Pakistan to increase ranges of up to 4500 km. The Babur cruise missile range can also be extended to 1000 km or more. These land-based missiles are controlled by Army Strategic Forces Command of Pakistan Army.

Aerial systems

The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) is believed to have practiced "toss-bombing" in the 1980s and 1990s, a method of launching weapons from fighter-bombers which can also be used to deliver nuclear warheads.[citation needed] The PAF has two units (No. 16 Black Panthers and No. 26 Black Spiders) operating around 50 of the Chinese-built Nanchang A-5C, believed to be the preferred vehicle for delivery of nuclear weapons due to its long range. These units are major part of the Air Force Strategic Command, a command responsible for battling the weapons of mass destruction. The others are various variants of the Mirage-III and Mirage-V, of which around 156 are currently operated by the PAF. The PAF also operates some 63 F-16 fighters, the first 32 of which were delivered in the 1980s and believed by some to have been modified for nuclear weapons delivery.[citation needed]

It has also been reported that an air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) with a range of 350 km has been developed by Pakistan, designated Hatf 8 and named Ra'ad ALCM, which may theoretically be armed with a nuclear warhead. It was reported to have been test-fired by a Mirage III fighter and, according to one Western official, is believed to be capable of penetrating some air defence/missile defence systems.[84]

The Pakistan Navy was first publicly reported to be considering deployment of nuclear weapons on submarines in February 2001. Later in 2003 it was stated by Admiral Shahid Karimullah, then Chief of Naval Staff, that there were no plans for deploying nuclear weapons on submarines but if "forced to" they would be. In 2004, Pakistan Navy established the Naval Strategic Forces Command and made it responsible for countering and battling naval-based weapons of mass destruction. It is believed by most experts that Pakistan is developing a sea-based variant of the Hatf VII Babur, which is a nuclear-capable ground-launched cruise missile.[85] With a stockpile of plutonium, Pakistan would be able to produce a variety of miniature nuclear warheads which would allow it to nuclear-tip the C-802 and C-803 anti-ship missiles as well as being able to develop nuclear torpedoes, nuclear depth bombs and nuclear naval mines.[citation needed]

See also

- Chronology of Pakistan's rocket tests

- Nuclear power in Pakistan

- Pakistan Army

- Pakistan Navy

- List of countries with nuclear weapons

References

- ^ a b "Pakistan Nuclear Weapons". Fas.org. http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/nuke/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b DeYoung, Karen (2011-01-31). "Pakistan doubles its nuclear arsenal". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/30/AR2011013004682.html.

- ^ "Hatf 6". MissileThreat. http://www.missilethreat.com/missilesoftheworld/id.54/missile_detail.asp. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Owl's Tree: Pakistani Nuclear Program 2-5". Owlstree.blogspot.com. 2006-06-10. http://owlstree.blogspot.com/2006/06/pakistani-nuclear-program-2-5.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b Ahmad, Mansoor; Usman Shabbir, Syed Ahmad H, Khan (2006). "Multan Conference January 1972: The Birth of Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons Program.". Pakistan Military Consortium (Islamabad, Pakistan: Pakistan Military Consortium) 1 (1): 16. http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:OZFTUPnzBiEJ:www.pakdef.info/ereporter/pakdefereportervol1no1.pdf+Nuclear+pakdef+pdf&hl=en&gl=us&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESieytaoc5d0ZMNaZGigsHyiMo17j4BEBpUU-1okQ5Ri77lRJcRUqofaURTdifYPjzKobJTrdf9ZuTQv-4YafN7XZCPeQ_G7N0DvnZ3b4YzhKEX9Nclii5tMErLUiDSM4YzzDryG&sig=AHIEtbTGuqcEBbws1m56OIsaBU7jlpAoyQ. Retrieved 2010.

- ^ a b "Bhutto was father of Pakistan's nuclear weapons programme". http://www.iiss.org/whats-new/iiss-in-the-press/press-coverage-2007/may-2007/bhutto-was-father-of-pakistani-bomb/?locale=en. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ^ "Pakistan Nuclear Weapons". http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/nuke/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ a b Rehman, Shahid-ur (1999). "Chapter 3§ A Man in a Hurry for the Bomb.". Long Road to Chagai:. 1 (1 ed.). Islamabad, Islamabad Capital Territory: Printwise Publications. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9698500006

- ^ a b c d e "Pakistan Military Consortium". www.PakDef.info. http://www.pakdef.info/nuclear&missile/speech_munirahmed.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b Ahmad, Shamshad (July/August 1999). "The Nuclear Subcontinent: Bringing Stability to South Asia". Foreign Affairs. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/55222/shamshad-ahmad/the-nuclear-subcontinent-bringing-stability-to-south-asia. "It proposed a nuclear weapons-free zone in South Asia; a joint renunciation of acquisition or manufacture of nuclear weapons; mutual inspection of nuclear facilities; adherence to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards on nuclear facilities; a bilateral nuclear test ban; and a missile-free zone in South Asia."

- ^ a b c d "PakDef Forums". Pakdef.info. http://pakdef.info/forum/archive/index.php?t-8346.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b Pervez,, S.; M. Latif, I.H. Bokhari and S.Bakhtyar (2004). "Performance of PARR-I reactor with LEU fuel". Nuclear Engineering Division of Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology (PINSTECH) and Reduced Enrichment for Research and Test Reactors, Nuclear Engineering Division at Argonne National Laboratory (U.S. Department of Energy). Argonne National Laboratory. http://www.rertr.anl.gov/RERTR26/Abstracts/42-Pervez.html. Retrieved 2011.

- ^ a b PAEC and IAEA (2008-12-03). "Research Reactor Details - PARR-2". Nuclear Engineering Division of Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology (PINSTECH). Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology. http://www-naweb.iaea.org/napc/physics/research_reactors/database/rr%20data%20base/datasets/report/Pakistan,%20Islamic%20Republic%20of%20%20Research%20Reactor%20Details%20-%20PARR-2.htm. Retrieved 2011.

- ^ Duff, Michael (2007). Salam + 50: proceedings of the conference, §Abdus Salam and Pakistan. London, United Kingdom: Imperial College Press. pp. 42.

- ^ "NUCLEAR AND MISSILE PROLIFERATION (Senate - May 16, 1989)". Fas.org. http://www.fas.org/spp/starwars/congress/1989/890516-cr.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "IAEA gave legal justification to Pakistan to build nuclear power plants". Jang News. 2011. http://jang.com.pk/jang/mar2011-daily/10-03-2011/main2.htm. Retrieved 2011.

- ^ a b Haqqani, Hussain (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. United Book Press. ISBN 978-0-87003-214-1, 0-87003-223-2. http://books.google.com/?id=nYppZ_dEjdIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=., Chapter 3, pp 87.

- ^ a b c Langewiesche, William (November 2005). "The Wrath of Khan". The Atlantic. William Langewiesche of The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2005/11/the-wrath-of-khan/4333/3/. Retrieved August 2011.

- ^ Stengel, Richard (Monday, Jun. 03, 1985). "Who has the Bomb?". Time magazine: pp. 7/13. Archived from the original on Jun. 03, 1985. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,957761-7,00.html. Retrieved February 23, 2011

- ^ Shahid-Ur-, Rehman (1999). "A Manhattan Project Scientist". Long Road To Chagai. Islamabad, Pakistan: Print Wise Publication. pp. 23.

- ^ Rehman, Shahid (1999). Professor Abdus Salam and Pakistan's Nuclear Program. http://books.google.com/?id=sNMgAQAAIAAJ&q=Dr+Salam&dq=Abdus+Salam+long+road+to+chagai.

- ^ a b c d Rahman, Shahidur (1999) [1999]. "§The Theoretical Physics Group, a cue from Manhattan Project?". Long Road to Chagai. Islamabad, Islamabad Capital Territory: Printwise Publications. pp. 38–198. ISBN 9698500006. Archived from the original on 1999. http://books.google.com/books?id=sNMgAQAAIAAJ&q=Dr+Salam&dq=Abdus+Salam+long+road+to+chagai&hl=en

- ^ Shahidur Rehman, Long Road to Chagai, Professor Abdus Salam and Pakistan's Fission Weapons Programme, pp51-89, Printwise publications, Islamabad, 1999

- ^ Munir Ahmad Khan, How Pakistan made its nuclear fuel cycle, The Nation, (Islamabad) February 7 and 9, 1998.

- ^ Bhutto on Nuclear weapons

- ^ "War clouds hovering over South Asia". Weekly Blitz. 2009-01-16. http://www.weeklyblitz.net/index.php?id=295. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "The normative approach to nuclear proliferation.(Viewpoint essay) - International Journal on World Peace | HighBeam Research - FREE trial". Highbeam.com. 2006-03-01. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-152972617.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b "A.Q. Khan". www.globalsecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/pakistan/khan.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ Armstrong, David; Joseph John Trento, National Security News Service. America and the Islamic Bomb: The Deadly Compromise. Steerforth Press, 2007. p. 165. ISBN 1586421379,9781586421373.

- ^ "Eye To Eye: An Islamic Bomb". CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=3483035n&tag=mncol;lst;3.

- ^ http://www.expressindia.com/latest-news/Lankan-Muslims-in-Dubai-supplied-Nmaterials-to-Pak-A-Q-Khan/514870/

- ^ "On the trail of the black market bombs". BBC News. 2004-02-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3481499.stm.

- ^ a b "Pakistan Nuclear Weapons". Fas.org. http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/nuke/. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "When Mountains Move – The Story of Chagai". Defencejournal.com. http://www.defencejournal.com/2000/june/chagai.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ Pakistan's Nuke History: Part1 From A PAEC Perspective

- ^ a b c d NTI, Nuclear Threat Initiatives. "Pakistan: Biological Review". NTI Research on Countries. http://www.nti.org/e_research/profiles/Pakistan/Biological/index.html.

- ^ NTI, Nuclear Threat Initiatives. "Pakistan: Chemical Weapons Review". NTI Research on Countries with Chemical facilities and capabilities.. http://www.nti.org/e_research/profiles/Pakistan/Biological/index.html.

- ^ "Pakistan gets IAEA approval for new N-plant". Payvand.com. 2006-11-22. http://payvand.com/news/06/nov/1318.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Pakistan Builds 2 More Reactors: ISIS". Apakistannews.com. 2009-04-24. http://www.apakistannews.com/pakistan-builds-2-more-reactors-isis-117565. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 2009-05-29. http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2009\05\29\story_29-5-2009_pg7_1. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Security Verification". www.thenews.com.pk. http://www.thenews.com.pk/daily_detail.asp?id=180186. Retrieved 2010-08-21.[dead link]

- ^ "Global Beat: Mark Hibbs' Nuclear Watch: July 17, 1998". Bu.edu. http://www.bu.edu/globalbeat/nucwatch/nucwatch071798.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b "The dangers of India – Pakistan war". 1913 Intel. http://www.1913intel.com/2008/12/27/the-dangers-of-india-pakistan-war/. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "'Pakistan building third nuclear reactor at Khushab' | ISIS | David Albright | Indian Express". Expressbuzz.com. http://www.expressbuzz.com/edition/story.aspx?Title=Pakistan+building+third+nuclear+reactor+at+Khushab&artid=pQqZ2l/ffuU=&SectionID=oHSKVfNWYm0=&MainSectionID=oHSKVfNWYm0=&SectionName=VfE7I/Vl8os=&SEO=. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Uranium Institute News Briefing 00.25 14–22 June 2000". Uranium Institute. 2000. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23. http://web.archive.org/web/20060923194947/http://www.world-nuclear.org/nb/nb00/nb0025.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-07.

- ^ Key Issues: Nuclear Energy: Issues: IAEA: World Plutonium Inventories

- ^ BBC NEWS | World | South Asia | Pakistan nuclear report disputed

- ^ Pakistan Expanding Nuclear Program - washingtonpost.com

- ^ BBC NEWS | World | South Asia | Pakistan 'building new reactor'

- ^ U.S. Group Says Pakistan Is Building New Reactor - New York Times

- ^ Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945–2010, Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August, 2010.

- ^ Federation of American Scientists

- ^ Center for Defense Information

- ^ "US Navy Strategic Insights. Feb 2003". US Navy. 2003. http://www.ccc.nps.navy.mil/si/feb03/southAsia2.asp. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Pakistan's Nuclear Arsenal Underestimated, Reports Say

- ^ Impact of US wargames on Pakistan N-arms ‘negative’ -DAWN - Top Stories; 3 December 2007

- ^ Calculating the Risks in Pakistan - washingtonpost.com

- ^ a b "Pakistan's Nukes - Al-Qaeda's Next Strategic Surprise? - Defense Update News Analysis". Defense-update.com. http://defense-update.com/analysis/analysis_pakistan_240409.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "World | Pakistan enhances second strike N-capability: US report". Dawn.Com. http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/news/world/11-pakistan-enhances-second-strike-n-capability--us-report--il--12. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (4 May 2009). "Strife in Pakistan Raises U.S. Doubts Over Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/04/world/asia/04nuke.html?_r=1&hp. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Pakistan's growing nuclear programme". BBC News. 2010-12-01. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-11888973.

- ^ China tested N-weapons for Pak: US insider The Times of India 6 September 2008

- ^ "US Report: China gifted nuclear bomb and Pakistan stole the technology". TheWorldReporter.com. 2009-11-18. http://www.theworldreporter.com/2009/11/us-report-china-gifted-nuclear-bomb-and.html.

- ^ "Report No. 2001/10: Nuclear Weapons Proliferation". Csis-scrs.gc.ca. 2008-05-15. http://www.csis-scrs.gc.ca/pblctns/prspctvs/200110-eng.asp. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ "Research Library: Country Profiles: Pakistan". NTI. http://www.nti.org/e_research/profiles/Pakistan/Nuclear/chronology_1990.html. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ http://www.businessworld.in/bw/2011_01_22_The_Nuclear_Question.html

- ^ http://www.pakistanidefence.com/Nuclear&Missiles/nca.htm

- ^ "Pakistani PM takes charge of nuclear weapons". Reuters. November 29, 2009. http://in.reuters.com/article/topNews/idINIndia-44323120091129. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Broad, William J. (2007-11-18). "U.S. Secretly Aids Pakistan in Guarding Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/18/washington/18nuke.html?ref=us. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- ^ New York Times/18 November 2007

- ^ "International Institute for Strategic Studies Pakistan’s nuclear oversight reforms". Iiss.org. http://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/nbm/nuclear-black-market-dossier-a-net-assesment/pakistans-nuclear-oversight-reforms/. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b Are Pakistan's nuclear weapons safe?, BBC, 2008-01-23

- ^ Obama’s Worst Pakistan Nightmare, The New York Times, 2009-01-11

- ^ U.S. Policy and Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons: Containing Threats and Encouraging Regional Security, The Heritage Foundation, 2007-07-06

- ^ Elite US troops ready to combat Pakistani nuclear hijacks, The Times, 2010-01-17

- ^ Elisabeth Bumiller, "Gates Sees Fallout From Troubled Ties With Pakistan", published by The New York Times on 23 January 2010, URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/24/world/asia/24military.html. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ Pakistan nuclear weapons at risk of theft by terrorists, US study warns, The Guardian, 2010-04-12

- ^ Could terrorists get hold of a nuclear bomb?, BBC, 2010-04-12

- ^ Official: Terrorists seek nuclear material, but lack ability to use it, CNN, 2010-04-13

- ^ Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons: Proliferation and Security Issues, Congressional Research Service, 2010-02-23

- ^ Tehran Times: IAEA declares Pakistan nuclear program safe

- ^ IAEA declared Pakistan's Nuke programme safe and secure

- ^ IAEA terms Pakistan's programme, safe and secure

- ^ "Pakistan Unveils Cruise Missile". Power Politics. 2005-08-13. http://powerpolitics.org/?p=161. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ NTI, Nuclear Threat Initiatives ((updated June 2011)). "Pakistan's Naval capabilities: Submarine system". Research: Submarine Proliferation by countries.. NTI: Research: Submarine Proliferation by countries.. http://www.nti.org/db/submarines/pakistan/index.html. Retrieved 2011.

External links

- BCCI May have funded Bomb

- The Islamic Bomb - Tashbih Sayyed

- US Report: China Gifted Nuclear Bomb and Pakistan Stole the Technology

- The South Asian Strategic Stability Institute Weapons Related Datasets

- Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) Military and Weapons Section

- China,Pakistan and the Bomb The Declassified File on U.S. Policy, 1977-1997-----National Security Archives.

- http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/nuke/index.html

- Nuclear Notebook: Pakistan's nuclear program, 2005, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Jan/Feb 2002.

- Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons Program - The Beginning

- Pakistani Military Consortium

- Nuclear Files.org Pakistan's nuclear conflict with India- background and the current situation

- Nuclear Files.org Current information on nuclear stockpiles in Pakistan

- Ideas Pakistan - International Defense Exhibition at Karachi, Pakistan

- Defense Export Promotion Organization - Ministry of Defense

- Time line of Pakistan's nuclear weapon development and tests

- - Pakistani & Indian Missile Forces (Tarmuk missile mentioned here)

- - Annotated bibliography on Pakistan's nuclear weapons from the Alsos Digital Library

Categories:- Military of Pakistan

- Weapons of mass destruction

- Nuclear weapons programme of Pakistan

- Nuclear weapons programs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.