- Zippe-type centrifuge

-

The Zippe-type centrifuge is a device designed to collect Uranium-235. It was developed in the Soviet Union by a team of 60 Austrian and German scientists captured after World War II, working in detention. The centrifuge is named after the team's lead experimenter, Gernot Zippe.[1]

Contents

Background

Natural uranium consists of three isotopes; the majority (99.274 percent) is U-238, while approximately 0.72 percent is U-235 and the remaining 0.0055 percent is U-234. If natural uranium is enriched to contain 3 percent U-235, it can be used as fuel for light water nuclear reactors. If it is enriched to contain 90 percent Uranium-235, it can be used for nuclear weapons.

Centrifuge uranium enrichment

Enriching uranium is difficult because the isotopes are practically identical in chemistry and very similar in weight: U-235 is only 1.26% lighter than U-238. Separation efficiency in a centrifuge depends on weight difference. Separation of uranium isotopes requires a centrifuge that can spin at 1,500 revolutions per second (90,000 RPM). If we assume a rotor diameter of 20 cm (actual rotor diameter is likely to be less), this corresponds to a linear speed of greater than Mach 2 (Mach 1 = 340 m/s). For comparison, automatic washing machines operate at only about 12 to 25 revolutions per second during the spin cycle (720-1500 rpm), while turbines in automotive turbochargers can run up to around 150,000 - 200,000 rpm[2][3] (2500 - 3333 revolutions per second).

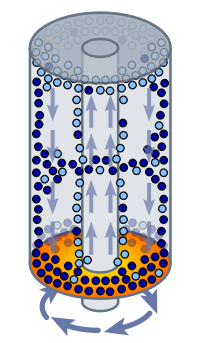

A Zippe-type centrifuge has a hollow, cylindrical rotor filled with gaseous uranium in the form of its hexafluoride. A pulsating magnetic field at the bottom of the rotor, similar to that used in an electric motor, is able to spin it quickly enough that the U-238 is thrown towards the edge. The lighter U-235 collects near the centre. The bottom of the gaseous mix is heated, producing convection currents that move the U-238 down. The U-235 moves up, where scoops collect it.[1] Each centrifuge has one inlet and two output lines (corresponding to the heavy and the light fractions).

At the high speed of rotation, the gas is compressed close to the wall of the rotor. The rotor can be almost a meter in length (diameter is likely to be less than 10 cm) and a temperature gradient of 300C between the top and bottom of the rotor produces a very strong convection current. In addition, very strong coriolis forces produced add to the separation efficiency.

To reduce friction, the rotor spins in a vacuum. A magnetic bearing holds the top of the rotor steady, and the only physical contact is the needle-like bearing that the rotor sits on.[1] The three gas lines must be concentric with the axis and the seal is very important.

After the scientists were released from Soviet captivity in 1956, Gernot Zippe was surprised to find that engineers in the West were years behind in their centrifuge technology. He was able to reproduce his design at the University of Virginia in the United States, publishing the results, even though the Soviets had confiscated his notes. Dr. Zippe left the United States when he was effectively barred from continuing his research: The Americans classified the work as secret, requiring him to become an American citizen (he refused), return to Europe, or abandon his research.[1] He returned to Europe where, during the 1960s, he and his colleagues made the centrifuge more efficient by changing the material of the rotor from aluminum to a stronger alloy called maraging steel, which allowed higher speed. This improved centrifuge design is used by the commercial company Urenco to produce enriched uranium fuel for nuclear power stations.[1]

The exact details of advanced Zippe-type centrifuges are closely guarded secrets, but the efficiency of the centrifuges is improved by making them longer, and increasing their speed of rotation. To do so, even stronger materials, such as carbon fiber reinforced composite materials are used, and various techniques are used to avoid forces causing destructive vibrations, including the use of flexible "bellows" to allow controlled flexing of the rotor, as well as careful speed control to ensure that the centrifuge does not operate for very long at speeds where resonance is a problem.

The Zippe-type is difficult to build successfully, and requires carefully machined parts. To give some idea of the precision required, it was reported in 2006 that the tiny amount of material deposited in fingerprints on Iran's prototype centrifuges were enough to cause the machines to shatter.[citation needed] However, compared to other enrichment methods, it is much cheaper and can be used in relative secrecy. This makes it ideal for covert nuclear-weapons programs and possibly increases the risk of nuclear proliferation. Centrifuge cascades also have much less material held in the machine at any time, unlike gaseous diffusion plants.

Global usage

In 2004 Abdul Qadeer Khan, a Pakistani engineer, admitted to operate a smuggling ring responsible for supplying at least three countries with Zippe-type centrifuges.[1]

Pakistan's nuclear program developed the P1 and P2 centrifuges—the first two centrifuges that Pakistan deployed in large numbers. The P1 centrifuge uses an aluminum rotor, and the P2 centrifuge uses a maraging steel rotor, which is stronger, spins faster, and enriches more uranium per machine than the P1.[4] The western sources allegedly claimed that Zippe-technology was significantly improved by a team of Pakistani scientists working in KRL when a Pakistani mathematician Dr. Tasneem M. Shah had improvised and developed the new version of the technology.

Russian and Soviet sources dispute the account of Soviet centrifuge development given by Gernot Zippe. They cite Prof. Max Steenbeck as the actual German scientist in charge of the German part of the Soviet centrifuge effort, which was started by German refugee Fritz Lange in the 1930s. The Soviets credit Steenbeck, Lange, Isaac Kikoin and Evgeni Kamenev with originating different valuable aspects of the design. They state Zippe was engaged in building prototypes for the project for two years from 1953. Since the centrifuge project was top secret the Soviets did not challenge any of Zippe's claims at the time.[5]

See also

- Isotope separation

- Gas centrifuge

- Ultracentrifuge

- Magnetic levitation

- Thrust bearing

- German nuclear energy project

- Germany and weapons of mass destruction

- Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction

- Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union

- Russian Alsos

- Gernot Zippe

- Abdul Qadeer Khan

- Stuxnet

References

- ^ a b c d e f Broad, William J. (2004-03-23). "Slender and Elegant, It Fuels the Bomb". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/23/science/slender-and-elegant-it-fuels-the-bomb.html. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ http://forcedairresearch.tripod.com/id4.html

- ^ http://auto.howstuffworks.com/turbo.htm/printable

- ^ http://www.cramster.com/reference/wiki.aspx?wiki_name=Zippe-type_centrifuge

- ^ RUSSIA’S GASEOUS CENTRIFUGE TECHNOLOGY AND URANIUM ENRICHMENT COMPLEX

External links

- The Zippe Type - The Poor Man's Bomb, BBC Radio 4, 19 May 2004

- Tracking the technology, Nuclear Engineering International, 31 August 2004

- Slender and Elegant, It Fuels the Bomb, The New York Times, March 23, 2004

- The Gas Centrifuge and Nuclear Proliferation, Marvin Miller, October 22, 2004

- The gas centrifuge and nuclear weapons proliferation, Houston G. Wood, Alexander Glaser, and R. Scott Kemp,

Physics Today page 40, September 2008

Categories:- Centrifuges

- Isotope separation

- Uranium

- Science and technology in the Soviet Union

- Soviet inventions

- Germany–Soviet Union relations

- Nuclear technology in Pakistan

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.