- Lhasa

-

For other uses, see Lhasa (disambiguation).

- This article is about the urban area of Lhasa. See Lhasa Prefecture for the wider prefecture

Lhasa

拉萨

ལྷ་ས་

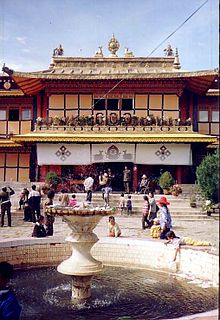

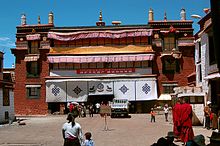

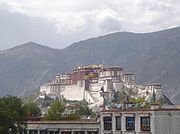

Lasa— Prefecture-level city — 拉萨市 · ལྷ་ས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར་ From top: The Potala Palace, Lhasa's most famous landmark, a city view of Lhasa, Barkor Street, and Jokhang Square Location in the Tibet Autonomous Region Location in China Coordinates: 29°39′N 91°07′E / 29.65°N 91.117°E Country People's Republic of China Region Tibet Government – Mayor Doje Cezhug – Deputy mayor Jigme Namgyal Area – Land 53 km2 (20.5 sq mi) Elevation 3,490 m (11,450 ft) Population (2009) – Prefecture-level city 1,100,123 – Urban 373,000 – Major Nationalities Tibetan; Han; Hui – Languages Tibetan, Mandarin, Jin language (Hohhot dialect) Time zone China Standard Time (UTC+8) Area code(s) 850000 Website http://www.lasa.gov.cn/ Lhasa Chinese name Traditional Chinese 拉薩 Simplified Chinese 拉萨 Hanyu Pinyin Lāsà Literal meaning place of the gods Transcriptions Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin Lāsà Min - Hokkien POJ la sat Wu - Romanization la平sah入 Cantonese (Yue) - Jyutping laai1saat3 Tibetan name Tibetan ལྷ་ས་ Transcriptions - Wylie lha sa - THDL Lhasa - Zangwen Pinyin Lhasa - Lhasa dialect IPA [l̥ásə] or [l̥ɜ́ːsə] Lhasa (

/ˈlɑːsə/, Tibetan: ལྷ་ས་, [l̥ásə] or [l̥ɜ́ːsə]; simplified Chinese: 拉萨; traditional Chinese: 拉薩; pinyin: Lāsà; sometimes spelled Lasa) is the administrative capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China and the second most populous city on the Tibetan Plateau, after Xining. At an altitude of 3,490 metres (11,450 ft), Lhasa is one of the highest cities in the world. It contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist sites such as the Potala Palace, Jokhang and Norbulingka palaces.

/ˈlɑːsə/, Tibetan: ལྷ་ས་, [l̥ásə] or [l̥ɜ́ːsə]; simplified Chinese: 拉萨; traditional Chinese: 拉薩; pinyin: Lāsà; sometimes spelled Lasa) is the administrative capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China and the second most populous city on the Tibetan Plateau, after Xining. At an altitude of 3,490 metres (11,450 ft), Lhasa is one of the highest cities in the world. It contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist sites such as the Potala Palace, Jokhang and Norbulingka palaces.Lhasa is part of the Lhasa Prefecture which consists of seven small counties: Lhünzhub County, Damxung County, Nyêmo County, Qüxü County, Doilungdêqên County, Dagzê County and Maizhokunggar County.

Contents

Etymology

Lhasa literally means "place of the gods". Ancient Tibetan documents and inscriptions demonstrate that the place was called Rasa, which either meant "goats' place", or, as a contraction of rawe sa, a "place surrounded by a wall,"[1] or 'enclosure', suggesting that the site was originally a hunting preserve within the royal residence on Marpori Hill.[2] Lhasa is first recorded as the name, referring to the area's temple of Jowo, in a treaty drawn up between China and Tibet in 822 C.E.[3]

History

By the mid 7th century, Songtsän Gampo became the leader of the Tibetan Empire that had risen to power in the Brahmaputra River (locally known as the Yarlung Zangbo River) Valley. After conquering the kingdom of Zhangzhung in the west, he moved the capital from the Chingwa Taktse castle in Chongye County (pinyin: Qióngjié Xiàn), southwest of Yarlung, to Rasa (modern Lhasa) where in 637 he raised the first structures on the site of what is now the Potala Palace on Mount Marpori.

In CE 639 and 641, Songtsän Gampo, who by this time had conquered the whole Tibetan region, is said to have contracted two alliance marriages, firstly to a Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and then, two years later, to Princess Wen Cheng of the Imperial Tang court. Bhrikuti is said to have converted him to Buddhism, which was also the faith attributed to his second wife Wen Cheng. In 641 he constructed the Jokhang (or Rasa Trülnang Tsulagkhang) and Ramoche Temples in Lhasa in order to house two Buddha statues, the Akshobhya Vajra (depicting the Buddha at the age of eight) and the Jowo Sakyamuni (depicting Buddha at the age of twelve), respectively brought to his court by the princesses. Lhasa suffered extensive damage under the reign of Langdarma in the 9th century, when the sacred sites were destroyed and desecrated and the empire fragmented.[4]

A Tibetan tradition mentions that after Songtsän Gampo's death in 649 C.E., Chinese troops captured Lhasa and burnt the Red Palace.[5][6] Chinese and Tibetan scholars have noted that the event is mentioned neither in the Chinese annals nor in the Tibetan manuscripts of Dunhuang. Lǐ suggested that this tradition may derive from an interpolation.[7] Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa believes that "those histories reporting the arrival of Chinese troops are not correct."[6]

From the fall of the monarchy in the 9th century to the accession of the 5th Dalai Lama, the centre of political power in the Tibetan region was not situated in Lhasa. However, the importance of Lhasa as a religious site became increasingly significant as the centuries progressed.[8] It was known as the centre of Tibet where Padmasambhava magically pinned down the earth demoness and built the foundation of the Jokhang Temple over her heart.[9]

By the 15th century, the city of Lhasa had risen to prominence following the founding of three large Gelugpa monasteries by Je Tsongkhapa and his disciples. The three monasteries are Ganden, Sera and Drepung which were built as part of the puritanical Buddhist revival in Tibet.[10] The scholarly achievements and political know-how of this Gelugpa Lineage eventually pushed Lhasa once more to centre stage.

The fifth Dalai Lama, Lobsang Gyatso (1617–1682), conquered Tibet and, in 1642, moved the centre of his administration to Lhasa, which thereafter became both the religious and political capital. In 1645, the reconstruction of the Potala Palace began on Red Hill. In 1648, the Potrang Karpo (White Palace) of the Potala was completed, and the Potala was used as a winter palace by the Dalai Lama from that time onwards. The Potrang Marpo (Red Palace) was added between 1690 and 1694.The name Potala is derived from Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of the Dalai Lama's divine prototype, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. The Jokhang Temple was also greatly expanded around this time. Although some wooden carvings and lintels of the Jokhang Temple date to the 7th century, the oldest of Lhasa's extant buildings, such as within the Potala Palace, the Jokhang and some of the monasteries and properties in the Old Quarter date to this second flowering in Lhasa's history.

By the end of the 17th century, Lhasa's Barkhor area formed a bustling market for foreign goods. The Jesuit missionary, Ippolito Desideri reported in 1716 that the city had a cosmopolitan community of Mongol, Chinese, Muscovite, Armenian, Kashmiri, Nepalese and Northern Indian traders. Tibet was exporting musk, gold, medicinal plants, furs and yak tails to far-flung markets, in exchange for sugar, tea, saffron, Persian turquoise, European amber and Mediterranean coral.[11]

By the 20th century, Lhasa, long a beacon for both Tibetan and foreign Buddhists, had numerous ethnically and religiously distinct communities, among them Kashmiri Muslims, Ladakhi merchants, Sikh converts to Islam, and Chinese traders and officials. The Kashmiri Muslims (Khache) trace their arrival in Lhasa to the Muslim saint of Patna, Khair ud-Din, contemporary with the 5th Dalai Lama.[12] Chinese Muslims lived in a quarter to the south, Nepalese families to the north, of the Barkhor market. Residents of the Lubu neighbourhood were descended from assimilated Chinese vegetable farmers who stayed over after accompanying an Amban from Sichuan in the mid-nineteenth century, intermarrying with Tibetan women and adopting Tibetan language and culture.[13] The city's merchants catered to all kinds of tastes, importing even Australian butter and British whisky. In the 1940s, according to Heinrich Harrer:-

-

'There is nothing one cannot buy, or at least order. One even finds the Elizabeth Arden specialties, and there is a keen demand for them. . .You can order, too, sewing machines, radio sets and gramophones and hunt up Bing Crosby records.'[14]

Such markets and consumerism came to an abrupt end after the arrival of Chinese government troops and administrative cadres in 1950.[15] Food rations and poorly stocked government stores replaced the old markets, until the 1990s when commerce in international wares once more returned to Lhasa,[16] and arcades and malls with a cornucopia of goods sprang up.[17]

Of the 22 parks (lingkas) which surrounded the city of Lhasa, most of them over half a mile in length, where the people of Lhasa were accustomed to picnic, only three survive today: the Dalai Lama's Summer Palace, constructed by the 7th Dalai Lama;[10] a small part of the Shugtri Lingka (now the 'People's Park'); and the Lukhang. Dormitory blocks, offices and army barracks are built over the rest.[18]

The Guāndì miào:(關帝廟) or Gesar Lhakhang temple was erected by the Amban in 1792 atop Mount Bamare 3 kilometres south of the Potala to celebrate the defeat of an invading Gurkha army.[19]

The main gate to the city of Lhasa used to run through the large Pargo Kaling chorten and contained holy relics of the Buddha Mindukpa.[20]

How the city of Lhasa looked from the Potala Palace in 1938

How the city of Lhasa looked from the Potala Palace in 1938

Between 1987–1989 Lhasa experienced major demonstrations, led by monks and nuns, against the Chinese Government. After Deng Xiao Ping's southern tour in 1992, however, Lhasa was declared a special economic zone. All government employees, their families and students are forbidden to practice their religion, while monks and nuns are forbidden from entering government offices and the Tibet University campus. Subsequent to the introduction of the special economic zone, the influx of migrants has dramatically altered the city's ethnic mix in Lhasa.[21]

In 2000 the urbanised area covered 53 sq.kilometres, with a population of around 170,000. Official statistics of the metropolitan area report that 70% are Tibetan, 34.3 are Han, and the remaining 2.7 Hui, though outside observers suspect that non-Tibetans account for some 50-70%. Among the Han immigrants, Lhasa is known as ‘Little Sichuan'.[21]

Geography

Lhasa sits in a flat river valley in the Himalaya Mountains.

Lhasa sits in a flat river valley in the Himalaya Mountains.

Lhasa Prefecture covers an area of close to 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi). It has a central area of 544 km2 (210 sq mi)[22] and a total population of 500,000; 250,000 of its people live in the urban area. Lhasa is home to the Tibetan, Han, and Hui peoples, as well as several other ethnic groups, but overall the Tibetan ethnic group makes up a majority of the total population.

View from Potala Palace today

View from Potala Palace today

Located at the bottom of a small basin surrounded by the Himalaya Mountains, Lhasa has an elevation of about 3,600 m (11,800 ft)[23] and lies in the centre of the Tibetan Plateau with the surrounding mountains rising to 5,500 m (18,000 ft). The air only contains 68% of the oxygen compared to sea level.[24] The Kyi River (or Kyi Chu), a tributary of the Yarlung Zangbo River), runs through the southern part of the city. This river, known to local Tibetans as the "merry blue waves,", flows through the snow-covered peaks and gullies of the Nyainqêntanglha mountains, extending 315 km (196 mi), and emptying into the Yarlung Zangbo River at Qüxü, forms an area of great scenic beauty. The marshlands, mostly uninhabited, are to the north.[25] Ingress and egress roads run east and west, while to the north, the road infrastructure is less developed.[25]

Climate

Due to its very high elevation, Lhasa has a cool semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) with frosty winters and mild summers, yet the valley location protects the city from intense cold or heat and strong winds. The city enjoys nearly 3,000 hours of sunlight annually and is thus sometimes called the "sunlit city" by Tibetans. The coldest month is January with an average temperature of −1.6 °C (29.1 °F) and the warmest month is June with a daily average of 16.0 °C (60.8 °F), though nights have generally been warmer in July.[26] The annual mean temperature is 7.98 °C (46.4 °F), with extreme temperatures ranging from −16.5 to 30.4 °C (2 to 87 °F).[27] Lhasa has an annual precipitation of 426 millimetres (16.8 in) with rain falling mainly in July, August and September. The driest month is January at 0.8 millimetres (0.03 in) and the wettest month is August, at 120.6 millimetres (4.75 in). The rainy season is widely regarded the "best" of the year as rains come mostly at night and Lhasa is still sunny during the daytime.

Climate data for Lhasa (1971−2000) Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Average high °C (°F) 7.2

(45.0)9.3

(48.7)12.7

(54.9)15.9

(60.6)19.9

(67.8)23.2

(73.8)22.6

(72.7)21.4

(70.5)19.9

(67.8)17.0

(62.6)12.1

(53.8)8.0

(46.4)15.8 Average low °C (°F) −9

(15.8)−5.8

(21.6)−2.1

(28.2)1.5

(34.7)5.6

(42.1)9.8

(49.6)10.4

(50.7)9.7

(49.5)7.7

(45.9)2.0

(35.6)−4.2

(24.4)−8.2

(17.2)1.5 Precipitation mm (inches) .8

(0.031)1.2

(0.047)2.9

(0.114)6.1

(0.24)27.7

(1.091)71.2

(2.803)116.6

(4.591)120.6

(4.748)68.3

(2.689)8.8

(0.346)1.3

(0.051)1.0

(0.039)426.5

(16.791)% humidity 28 26 27 37 44 51 62 66 63 49 38 34 43.8 Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) .7 1.0 1.6 4.3 9.9 14.3 19.1 20.0 15.4 4.5 .7 .6 92.1 Sunshine hours 250.9 226.7 246.1 248.9 276.6 257.3 227.4 219.6 229.0 281.7 267.4 258.6 2,990.2 Source: China Meteorological Administration [26] Government and politics

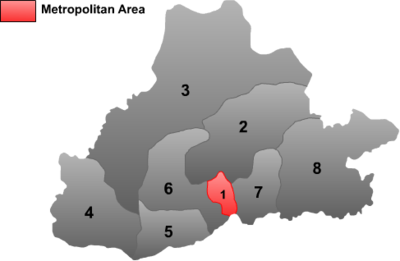

Lhasa prefecture-level city in Tibet Autonomous Region

Lhasa prefecture-level city in Tibet Autonomous Region Main article: Lhasa Prefecture

Main article: Lhasa PrefectureAdministratively speaking, Lhasa is a prefecture-level city that consists of one district and seven counties. Chengguan District is the main urban area of Lhasa. The mayor and vice-mayor of Lhasa are Doje Cezhug and Jigme Namgyal, respectively.

Map # Name Hanzi Hanyu Pinyin Tibetan Wylie Population (2003 est.) Area (km²) Density (/km²)

City proper 1 Chengguan District 城关区 Chéngguān Qū ཁྲིན་ཀོན་ཆུས་ khrin kon chus 140,000 525 267 Rural 2 Lhünzhub County 林周县 Línzhōu Xiàn ལྷུན་གྲུབ་རྫོང་ lhun grub rdzong 60,000 4,100 14 3 Damxung County 当雄县 Dāngxióng Xiàn འདམ་གཞུང་རྫོང dam gzhung rdzong 40,000 10,234 4 4 Nyêmo County 尼木县 Nímù Xiàn སྙེ་མོ་རྫོང་ snye mo rdzong 30,000 3,266 9 5 Qüxü County 曲水县 Qūshuǐ Xiàn ཆུ་ཤུར་རྫོང་ chu shur rdzong 30,000 1,624 18 6 Doilungdêqên County 堆龙德庆县 Duīlóngdéqìng Xiàn སྟོད་ལུང་བདེ་ཆེན་རྫོང་ stod lung bde chen rdzong 40,000 2,672 15 7 Dagzê County 达孜县 Dázī Xiàn སྟག་རྩེ་རྫོང་ stag rtse rdzong 30,000 1,361 22 8 Maizhokunggar County 墨竹工卡县 Mòzhúgōngkǎ Xiàn མལ་གྲོ་གུང་དཀར་རྫོང་ mal gro gung dkar rdzong 40,000 5,492 7 Economy

Competitive industry together with feature economy play key roles in the development of Lhasa. With the view to maintaining a balance between population growth and the environment, tourism and service industries are emphasised as growth engines for the future. Many of Lhasa's rural residents practice traditional agriculture and animal husbandry. Lhasa is also the traditional hub of the Tibetan trading network. For many years, chemical and car making plants operated in the area and this resulted in significant pollution, a factor which has changed in recent years. Copper, lead and zinc are mined nearby and there is ongoing experimentation regarding new methods of mineral mining and geothermal heat extraction.

Agriculture and animal husbandry in Lhasa are considered to be of a high standard. People mainly plant highland barley and winter wheat. The resources of water conservancy, geothermal heating, solar energy and various mines are abundant. There is widespread electricity together with the use of both machinery and traditional methods in the production of such things as textiles, leathers, plastics, matches and embroidery. The production of national handicrafts has made great progress.

With the growth of tourism and service sectors, the sunset industries which cause serious pollution are expected to fade in the hope of building a healthy ecological system. Environmental problems such as soil erosion, acidification, and loss of vegetation are being addressed. The tourism industry now brings significant business to the region, building on the attractiveness of the Potala Palace, the Jokang, the Norbulingka Summer Palace and surrounding large monasteries as well the spectacular Himalayan landscape together with the many wild plants and animals native to the high altitudes of Central Asia. Tourism to Tibet dropped sharply following the crackdown on protests in 2008, but as early as 2009, the industry was recovering.[28] Chinese authorities plan an ambitious growth of tourism in the region aiming at 10 million visitors by 2020; these visitors are expected to be domestic. With renovation around historic sites, such as the Potala Palace, UNESCO has expressed "concerns about the deterioration of Lhasa's traditional cityscape."[29]

Lhasa contains several hotels. Lhasa Hotel is a 4-star hotel located northeast of Norbulingka in the western suburbs of the city. Completed in September 1985, it is the flagship of CITS's installations in Tibet. It accommodates about 1000 guests and visitors to Lhasa. There are over 450 rooms (suites) in the hotel, and all are equipped with air conditioning, mini-bar and other basic facilities. Some of the rooms are decorated in traditional Tibetan style. The hotel was operated by Holiday Inn from 1986 to 1997[30] and is the subject of the book: The Hotel on the Roof of the World. Another hotel of note is the historical Banak Shöl Hotel, located at 8 Beijing Road in the city.[31] It is known for its distinctive wooden verandas. The Nam-tso Restaurant is located in the vicinity of the hotel and is frequented especially by Chinese tourists visiting Lhasa.

Lhasa contains several businesses of note. Lhasa Carpet Factory, a factory south of Yanhe Dong Lu near the Tibet University produces traditional Tibetan rugs that are exported worldwide It is a modern factory; the largest manufacturer of rugs throughout Tibet employing some 300 workers. Traditionally Tibetan women were the weavers, and men the spinners, but both work on the rugs today.

The Lhasa Brewery Company was established in 1988 on the northern outskirts of Lhasa, south of Sera Monastery and is the highest commercial brewery in the world at 11,975 feet (3,650 m) and accounts for 85% of contemporary beer production in Tibet.[32] The brewery, consisting of five story buildings, cost an estimated US$20–25 million, and by 1994, production had reached 30,000 bottles per day, employing some 200 workers by this time.[33] Since 2000, the Carlsberg group has increased its stronghold in the Chinese market and has become increasingly influential in the country with investment and expertise. Carlsberg invested in the Lhasa Brewery in recent years and has drastically improved the brewing facility and working conditions, renovating and expanding the building to what now covers 62,240 square metres (15.3 acres).[34][35]

Demographics

Demographics in the past

The 11th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica published between 1910–1911 noted the total population of Lhasa, including the lamas in the city and vicinity was about 30,000;[36] a census in 1854 made the figure 42,000, but it is known to have greatly decreased since. Britannica noted that within Lhasa, there were about a total of 1,500 resident Tibetan laymen and about 5,500 Tibetan women.[36] The permanent population also included Chinese families (about 2,000).[36] The city's residents included people from Nepal and Ladak (about 800), and a few from Bhutan, Mongolia and other places.[36] The Britannica noted with interest that the Chinese had a crowded burial-ground at Lhasa, tended carefully after their manner and that the Nepalese supplied mechanics and metal-workers at that time.[36]

In the first half of the 20th century, several Western explorers made celebrated journeys to the city, including William Montgomery McGovern, Francis Younghusband, Alexandra David-Néel and Heinrich Harrer. As Lhasa was the centre of Tibetan Buddhism nearly half of its population were monks.

The majority of the pre 1950 Chinese population of Lhasa were merchants and officials. In the Lubu section of Lhasa, the inhabitants were descendants of Chinese men who married Tibetan women. They came to Lhasa in the 1840s-1860s when a Chinese was appointed to the position of Amban. and they grow vegetables around Lubu, and identify themselves as Tibetans. Many of the children of the Lubu citizens went to the Lhasa Kuomintang school.[37]

According to one writer, the population of the city was about 10,000, with some 10,000 monks at Drepung and Sera monasteries in 1959[38] Hugh Richardson, on the other hand, puts the population of Lhasa in 1952, at "some 25,000–30,000—about 45,000–50,000 if the population of the great monasteries on its outskirts be included."[39]

An elderly Tibetan woman holding a prayer wheel on the street in Lhasa

An elderly Tibetan woman holding a prayer wheel on the street in Lhasa

Woman with son busking in Lhasa, 1993.

Woman with son busking in Lhasa, 1993.

Contemporary Demographics

The total population of Lhasa Prefecture-level City is 521,500 (including known migrant population but excluding military garrisons). Of this, 257,400 are in the urban area (including a migrant population of 100,700), while 264,100 are outside.[40] Nearly half of Lhasa Prefecture-level City's population lives in Chengguan District, which is the administrative division that contains the urban area of Lhasa (i.e. the actual city).

In terms of ethnic makeup, the exile Central Tibetan Administration asserts that ethnic Tibetans are a minority in Lhasa. An ethnic dynamic was speculated to have influenced the 2008 Tibetan unrest. However, according to the November 2000 census, the ethnic distribution in Lhasa Prefecture-level City was as follows:

Major ethnic groups in Lhasa Prefecture-level City by district or county, 2000 census[41] Total Tibetans Han Chinese others Lhasa Prefecture-level City 474,499 387,124 81.6% 80,584 17.0% 6,791 1.4% Chengguan District 223,001 140,387 63.0% 76,581 34.3% 6,033 2.7% Lhünzhub County 50,895 50,335 98.9% 419 0.8% 141 0.3% Damxung County 39,169 38,689 98.8% 347 0.9% 133 0.3% Nyêmo County 27,375 27,138 99.1% 191 0.7% 46 0.2% Qüxü County 29,690 28,891 97.3% 746 2.5% 53 0.2% Doilungdêqên County 40,543 38,455 94.8% 1,868 4.6% 220 0.5% Dagzê County 24,906 24,662 99.0% 212 0.9% 32 0.1% Maizhokunggar County 38,920 38,567 99.1% 220 0.6% 133 0.3% Architecture and cityscape

Main article: Architecture of LhasaLhasa has many sites of historic interest, including the Potala Palace, Jokhang Temple, Sera Monastery and Norbulingka. The Potala Palace, Jokhang Temple and the Norbulingka are UNESCO world heritage sites.[42] However, many important sites were damaged or destroyed mostly, but not solely, during China's Cultural Revolution of the 1960s.[43][44][45] Many have been restored since the 1980s.

The Potala Palace

The Potala Palace

The Potala Palace, named after Mount Potala, the abode of Chenresig or Avalokitesvara,[46] was the chief residence of the Dalai Lama. After the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India during the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the government converted the palace into a museum. The site was used as a meditation retreat by King Songtsen Gampo, who in 637 built the first palace there in order to greet his bride Princess Wen Cheng of the Tang Dynasty of China. Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the Potala Palace in 1645[47] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (d. 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[48] The palace underwent restoration works between 1989 to 1994, costing RMB55 million (US$6.875 million) and was inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994.

The graceful Lhasa Zhol Pillar, below the Potala, dates as far back as circa 764 CE.[49] and is inscribed with what may be the oldest known example of Tibetan writing.[50] The pillar contains dedications to a famous Tibetan general and gives an account of his services to the king including campaigns against China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xian) in 763 CE[51] during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen's father, Me Agtsom.[52][53]

Chokpori, meaning 'Iron Mountain', is a sacred hill, located south of the Potala. It is considered to be one of the four holy mountains of central Tibet and along with two other hills in Lhasa represent the "Three Protectors of Tibet.", Chokpori (Vajrapani), Pongwari (Manjushri), and Marpori (Chenresig or Avalokiteshvara).[54] It was the site of the most famous medical school Tibet, known as the Mentsikhang, which was founded in 1413. It was conceived of by Lobsang Gyatso, the "Great" 5th Dalai Lama, and completed by the Regent Sangye Gyatso (Sangs-rgyas rgya-mtsho)[55] shortly before 1697.

Lingkhor is a sacred path, most commonly used to name the outer pilgrim road in Lhasa matching its inner twin, Barkhor. The Lingkhor in Lhasa was 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) long enclosing Old Lhasa, the Potala and Chokpori hill. In former times it was crowded with men and women covering its length in prostrations, beggars and pilgrims approaching the city for the first time. The road passed through willow-shaded parks where the Tibetans used to picnic in summer and watch open air operas on festival days. New Lhasa has obliterated most of Lingkhor, but one stretch still remains west of Chokpori.

The Norbulingka palace and surrounding park is situated in the west side of Lhasa, a short distance to the southwest of Potala Palace and with an area of around 36 hectares (89 acres), it is considered to be the largest man made garden in Tibet.[56][57] It was built from 1755.[58] and served as the traditional summer residence of the successive Dalai Lamas until the 14th's self-imposed exile. Norbulingka was declared a ‘National Important Cultural Relic Unit”, in 1988 by the State council. In 2001, the Central Committee of the Chinese Government in its 4th Tibet Session resolved to restore the complex to its original glory. The Sho Dun Festival (popularly known as the "yogurt festival") is an annual festival held at Norbulingka during the seventh Tibetan month in the first seven days of the Full Moon period, which corresponds to dates in July/August according to the Gregorian calendar.

The Barkhor is an area of narrow streets and a public square in the old part of the city located around Jokhang Temple and was the most popular devotional circumabulation for pilgrims and locals. The walk was about one kilometre long and encircled the entire Jokhang, the former seat of the State Oracle in Lhasa called the Muru Nyingba Monastery, and a number of nobles' houses including Tromzikhang and Jamkhang. There were four large incense burners (sangkangs) in the four cardinal directions, with incense burning constantly, to please the gods protecting the Jokhang.[59] Most of the old streets and buildings have been demolished in recent times and replaced with wider streets and new buildings. Some buildings in the Barkhor were damaged in the 2008 unrest.[60]

The Jokhang is located on Barkhor Square in the old town section of Lhasa. For most Tibetans it is the most sacred and important temple in Tibet. It is in some regards pan-sectarian, but is presently controlled by the Gelug school. Along with the Potala Palace, it is probably the most popular tourist attraction in Lhasa. It is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace," and a spiritual centre of Lhasa. This temple has remained a key center of Buddhist pilgrimage for centuries. The circumabulation route is known as the "kora" in Tibetan and is marked by four large stone incense burners placed at the corners of the temple complex. The Jokhang temple is a four-story construction, with roofs covered with gilded bronze tiles. The architectural style is based on the Indian vihara design, and was later extended resulting in a blend of Nepalese and Tang Dynasty styles. It possesses the statues of Chenresig, Padmasambhava and King Songtsan Gambo and his two foreign brides, Princess Wen Cheng (niece of Emperor Taizong of Tang China) and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and other important items.

Ramoche Temple is considered the most important temple in Lhasa after the Jokhang Temple. Situated in the northwest of the city, it is east of the Potala and north of the Jokhang,[61] covering a total area of 4,000 square meters (almost one acre). The temple was gutted and partially destroyed in the 1960s and its famous bronze statue disappeared. In 1983 the lower part of it was said to have been found in a Lhasa rubbish tip, and the upper half in Beijing. They have now been joined and the statue is housed in the Ramoche Temple, which was partially restored in 1986,[61] and still showed severe damage in 1993. Following the major restoration of 1986, the main building in the temple now has three stories.

The Tibet Museum in Lhasa is the official museum of the Tibet Autonomous Region and was inaugurated on October 5, 1999. It is the first large-sized modern museum in the Tibet Autonomous Region and has a permanent collection of around 1000 artefacts, from examples of Tibetan art to architectural design throughout history such as Tibetan doors and beams.[62][63] It is located in an L-shaped building, located directly below the Potala Palace on the corner of Norbulingkha Road. The museum is structured into three main sections: a main exhibition hall, a folk cultural garden and an administrative quarter.[62]

The Monument to the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet was unveiled in the Potala Square in May 2002 to celebrate the 51st anniversary of the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, and the work in the development of the autonomous region since then. The 37-metre-high concrete monument is shaped as an abstract Mount Everest and its name is engraved with the calligraphy of former president Jiang Zemin, while an inscription describes the socioeconomic development experienced in Tibet in the past fifty years.[64]

Culture

Music and dance

There are some night spots that feature cabaret acts in which performers sing in English, Chinese, Tibetan, and Nepalese, and dancers wear traditional Tibetan costume with long flowing cloth extending from their arms. There are a number of small bars that feature live music, although they typically have limited drink menus and cater mostly to foreign tourists.

Education

Tibet University

Tibet University (Tibetan: Tibet University is the main university of the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Its campus is in Lhasa. A forerunner was created in 1952 and the university was officially established in 1985, funded by the Chinese government. About 8000 students are enrolled at the university.

Transport

The Qingzang Railway which proceeds north and then east to Xining, some 2000 km, goes up to 5,072 meters above sea level, is the highest railway in the world. Five trains arrive at and depart from Lhasa railway station each day. Train numbered T27 takes 43 hours, 51 minutes from Beijing West, arrives in Lhasa at 16:00 every day. T28 from Lhasa to Beijing West departs at 13:45 and arrives in Beijing at 08:06 on the third day, taking 42 hours, 21 minutes. There are also trains from Chengdu, Chongqing, Lanzhou, Xining, Guangzhou, Shanghai and other cities. To counter the problem of altitude differences giving passengers altitude sickness, extra oxygen is pumped in through the ventilation system, and personal oxygen masks are available on request.[65]

Lhasa Gonggar Airport is located about one hour's taxi ride south from the city. There are flight connections to several Chinese cities including Beijing and Chengdu, and to Kathmandu in Nepal. A new 37.68 kilometres (23.41 mi), four-lane highway between Lhasa and the Gonggar Airport has been built by the Transportation Department of Tibet at a cost of RMB 1.5 billion. This road,is part of National Highway 318 and starts from the Lhasa Railway Station, passes through Caina Township in Qushui County, terminates between the north entrance of the Gala Mountain Tunnel and the south bridge head of Lhasa River Bridge, and en-route goes over the first overpass of Lhasa at Liu Wu Overpass.[66] The Qinghai-Tibet Highway (part of G109) runs to northeast toward Xining and eventually to Beijing and is the mostly used road. The Sichuan-Tibet Highway (part of G318) runs east towards Chengdu and eventually to Shanghai. G318 also runs west toward Zhangmu on the Nepal border. The Xinjiang-Tibet Highway (G219) runs north to Yecheng, and then to Xinjiang. This road is rarely used due to the lack of amenities and petrol stations.

Sister cities

Lhasa has four sister cities:[67]

Boulder, Colorado, United States, since 1987

Boulder, Colorado, United States, since 1987 Potosí, Bolivia, since 1995

Potosí, Bolivia, since 1995 Elista, Kalmykia, Russia, since 2004

Elista, Kalmykia, Russia, since 2004 Beit Shemesh, Israel, since 2007

Beit Shemesh, Israel, since 2007

Footnotes

- ^ Anne-Marie Blondeau and Yonten Gyatso, 'Lhasa, Legend and History,' in Françoise Pommaret-Imaeda (ed.)Lhasa in the seventeenth century: the capital of the Dalai Lamas, BRILL, 2003, pp.15-38, pp.21-22.

- ^ John Powers, Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion Publications, 2007, p.144.

- ^ Anne-Marie Blondeau and Yonten Gyatso, 'Lhasa, Legend and History,' pp.21-22.

- ^ Dorje (1999), pp. 68-9.

- ^ Charles Bell (1992). Tibet Past and Present. CUP Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. p. 28. ISBN 8120810481. http://books.google.com/books?id=U7C0I2KRyEUC&pg=PA28&dq=chinese+captured+lhasa+650&hl=en&ei=zfRNTJCsOcT48Aa24vnyCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=chinese%20captured%20lhasa%20650&f=false. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ^ a b W. D. Shakabpa, Derek F. Maher (2010). One hundred thousand moons, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 123. ISBN 9004177884. http://books.google.com/books?id=lGyrymfDdI0C&pg=PA123&dq=Chinese+troops+Red+Palace,+correct&hl=en&ei=B90VTqXfMoihsQLl4elT&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Chinese%20troops%20Red%20Palace%2C%20correct&f=false. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Tieh-tseng Li, Tiezheng Li (1956). The historical status of Tibet. King's Crown Press, Columbia University. p. 6. http://books.google.com/books?ei=usMUTu6wEuXnsQKmn-DUDw&ct=result&id=hdVwAAAAMAAJ&dq=one+Tibetan+record+reports+%28and+this+may+be+a+later+interpolation%29+that+the+Chinese+captured+the+Tibetan+capital%2C+Lhasa%2C+after+the+death+of+Sron-tsan+Gampo.11+It+is+significant+that+neither+the+Chinese+historical+annals+nor+the+highly&q=lhasa+gampo++captured. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Bloudeau, Anne-Mari & Gyatso, Yonten. 'Lhasa, Legend and History' in Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas, 2003, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Bloudeau, Anne-Mari & Gyatso, Yonten. "Lhasa, Legend and History." In: Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas. Françoise Pommaret-Imaeda, Françoise Pommaret 2003, p. 38. Brill, Netherlands. ISBN 9789004128668.

- ^ a b Dorje (1999), p. 69.

- ^ Emily T. Yeh,'Living Together in Lhasa: Ethnic Relations, Coercive Amity, and Subaltern Cosmopolitanism,' in Shail Mayaram (ed.) The other global city, Taylor & Francis US. 2009, pp.54-85, pp.58-7.

- ^ John Bray, 'Trader, Middleman or Spy? The Dilemmas of a Kashmiri Muslim in Early Nineteenth-Century Tibet,' in Anna Akasoy, Charles Burnett, Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (eds.)Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2011, pp.313-338, p.315.

- ^ Emily T. Yeh,'Living Together in Lhasa: Ethnic Relations, Coercive Amity, and Subaltern Cosmopolitanism,' pp.59-60.

- ^ Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet, Penguin 1997 p.140, cited in Peter Bishop, The myth of Shangri-La: Tibet, travel writing, and the western creation of sacred landscape, University of California Press, 1989 p.192.

- ^ Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories, Columbia University Press, 2010 p.65

- ^ Emily T. Yeh,'Living Together in Lhasa: Ethnic Relations, Coercive Amity, and Subaltern Cosmopolitanism,' p.58.

- ^ Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories, p.104.

- ^ Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories, Columbia University Press, 2010 p.67.

- ^ Emily T. Yeh,'Living Together in Lhasa: Ethnic Relations, Coercive Amity, and Subaltern Cosmopolitanism,' p.60; The monument however does not commemorate the Tibetan epic hero, but the Chinese figure. See Lara Maconi, ‘Gesar de Pékin? Le sort du Roi Gesar de Gling, héros épique tibétain, en Chinese (post-) maoïste,’ in Judith Labarthe, Formes modernes de la poésie épique: nouvelles approches, Peter Lang, 2004 pp.371-419, p.373 n.7. Relying on H. Richardson, and R. A. Stein, Maconi says that this was erected by the Chinese general Fú kāng'ān (福康安).

- ^ Tung (1980), p.21 and caption to plate 17, p. 42.

- ^ a b Emily T. Yeh,'Living Together in Lhasa: Ethnic Relations, Coercive Amity, and Subaltern Cosmopolitanism,' p.70.

- ^ National Geographic Atlas of China (2007), p. 88. National Geographic, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1426201363.

- ^ National Geographic Atlas of China. (2008), p. 88. National Geographic, Washington D.C. ISBN 978-1-4262-0136-3.

- ^ Dorje (1999), p. 68.

- ^ a b Barnett, Robert (2006). Lhasa: streets with memories. Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 0231136803. http://books.google.com/books?id=MOCMLwQzD6kC&pg=PA42.

- ^ a b "中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年)" (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. http://cdc.cma.gov.cn/shuju/index3.jsp?tpcat=SURF&dsid=SURF_CLI_CHN_MUL_MMON_19712000_CES&pageid=3. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ Extreme Temperatures Around the world − world highest lowest temperatures. Accessed 2010-10-20

- ^ Xinhua, "Tibet tourism warms as spring comes", 2009-02-13.

- ^ Miles, Paul (8 April 2005). "Tourism drive 'is destroying Tibet'". London: Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/732642/Tourism-drive-is-destroying-Tibet.html. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ^ http://hotels.lonelyplanet.com/china/lhasa-r1973718/lhasa-hotel-p1037396/

- ^ Lonely Planet

- ^ "Lhasa beer from Tibet makes US debut". Tibet Sun. August 12, 2009. http://www.tibetsun.com/features/2009/08/12/lhasa-beer-from-tibet-makes-us-debut/. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Gluckman, Ron (1994). Brewing at the Top of the World. Asia, Inc.. http://www.gluckman.com/Lhasa%27Brew.html.

- ^ "Carlsberg China". Carlsberg Group. http://www.carlsberggroup.com/Company/Markets/Pages/China.aspx. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Beer". Lhasa Beer USA. http://www.lhasabeerusa.com/beer-d/the-brewery. Retrieved September 27, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e LHASA. Online Encyclopedia. Search over 40,000 articles from the original, classic Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition

- ^ Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 60. ISBN 0415991943. http://books.google.com/books?id=QVSVux0wIW0C&pg=PA60&dq=lubu+residents+sent+children++school+lhasa&hl=en&ei=1OvMTIKnBsaAlAeJ6YTlCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=lubu%20residents%20sent%20children%20%20school%20lhasa&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Dowman (1988), p. 39.

- ^ Richardson (1984), p. 7.

- ^ People's Government of Lhasa Official Website - "Administrative divisions"

- ^ Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司) and Department of Economic Development of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of China (国家民族事务委员会经济发展司), eds. Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》). 2 vols. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003. (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

- ^ "Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa". unesco. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/707. Retrieved 2008-02-10. In the surrounding prefecture of Lhasa are Sera Monastery and its many hermitages, many of which overlook Lhasa from the northern hill valleys and Drepung Monastery, amongst many others of historical importance.

- ^ Bradley Mayhew and Michael Kohn. Tibet. 6th Edition (2005), pp. 36-37. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-523-8

- ^ Keith Dowman. The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, (1988) pp. 8-13. Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd., London and New York. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- ^ Laird, Thomas. (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, pp. 345-351.Grove Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- ^ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization (1962). Translated into English with minor revisions by the author. 1st English edition by Faber & Faber, London (1972). Reprint: Stanford University Press (1972), p. 84

- ^ Laird, Thomas. (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, pp. 175. Grove Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- ^ Karmay, Samten C. (2005). "The Great Fifth", p. 1. Downloaded as a pdf file on 16 December 2007 from: [1]

- ^ Richardson (1985), p. 2.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1999). "Tibetan writing". Blackwell Reference Online. http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id=g9780631214816_chunk_g978063121481622_ss1-17. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ Snellgrove and Richardson (1995), p. 91.

- ^ Richardson (1984), p. 30.

- ^ Beckwith (1987), p. 148.

- ^ Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization, p. 228. Translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper).

- ^ Dowman, Keith. (1988). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, p. 49. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- ^ "Norbulingka Palace". Tibet Tours. http://www.tibettours.com/norbulingka.html. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ "Norbulingka". Cultural China. http://www.cultural-china.com/chinaWH/html/en/Scenery95bye384.html. Retrieved 2010=05-23.

- ^ Tibet (1986), p.71

- ^ Dowman, Keith (1998). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, pp. 40-41. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London and New York. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- ^ Philip, Bruno (19 March 2008). "Trashing the Beijing road". The Economist. http://www.economist.com/world/asia/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10875823. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ a b Dowman, Keith. 1988. The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, p. 59. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0 (ppk).

- ^ a b "The Tibet Museum". China Tibet Information Center. http://zt.tibet.cn/english/zt/culture/20040200451384554.htm. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ "Tibet Museum". China Museums. http://www.chinamuseums.com/tibet.htm. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ "Monument to Tibet Peaceful Liberation Unveiled". China Tibet Tourism Bureau. http://www.xzta.gov.cn/yww/Introduction/History/4949.shtml. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Cody, Edward (2006-07-04). "Train 27, Now Arriving Tibet, in a 'Great Leap West'". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/03/AR2006070301219.html. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "New highway linking Lhasa to Gonggar Airport to be built". http://english.chinatibetnews.com/news/Society/2009-08/12/content_287181.htm.

- ^ Lhasa city guide

References

- Das, Sarat Chandra. 1902. Lhasa and Central Tibet. Reprint: Mehra Offset Press, Delhi. 1988. ISBN 81-86230-17-3

- Dorje, Gyurme. 1999. Footprint Tibet Handbook. 2nd Edition. Bath, England. ISBN 1 900949 33 4. Also published in Chicago, U.S.A. ISBN 0 8442-2190-2.

- Dowman, Keith. 1988. The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, p. 59. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0 (ppk).

- Liu, Jianqiang (2006). chinadialogue - Preserving Lhasa's history (part one).

- Miles, Paul. (April 9, 2005). "Tourism drive 'is destroying Tibet' Unesco fears for Lhasa's World Heritage sites as the Chinese try to pull in 10 million visitors a year by 2020". Daily Telegraph (London), p. 4.

- Pelliot, Paul. (1961) Histoire ancienne du Tibet. Libraire d'Amérique et d'orient. Paris.

- Richardson, Hugh E (1984). Tibet and its History. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. Shambhala Publications, Boston. ISBN 0-87773-376-7.

- Richardson, Hugh E (1997). Lhasa. In Encyclopedia Americana international edition, (Vol. 17, pp. 281–282). Danbury, CT: Grolier Inc.

- Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization, p. 38. Reprint 1972. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper).

- Tung, Rosemary Jones. 1980. A Portrait of Lost Tibet. Thomas and Hudson, London. ISBN 0 500 54068 3.

- Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications. London. ISBN 0-906026-25-3.

- (2006). Lhasa - Lhasa Intro

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. (1981). Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. (608 pages, 1244 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-01-8

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. (2001). Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd.). ISBN 962-7049-07-7

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2008. 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet. (212 p., 112 colour illustrations) (DVD with 527 digital photographs). Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 962-7049-08-5

Further reading

- Desideri (1932). An Account of Tibet: The Travels of Ippolito Desideri 1712-1727. Ippolito Desideri. Edited by Filippo De Filippi. Introduction by C. Wessels. Reproduced by Rupa & Co, New Delhi. 2005

- Le Sueur, Alec (2001). The Hotel on the Roof of the World – Five Years in Tibet. Chichester: Summersdale. ISBN 978-1840241990. Oakland: RDR Books. ISBN 978-1571431011

External links

- People's Government of Lhasa Official Website (Chinese)

- Lhasa @ China Tibet Information Center

- Lhasa Nights art exhibition

- Grand temple of Buddha at Lhasa in 1902, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

Maps and aerial photos

Coordinates: 29°39′N 91°06′E / 29.65°N 91.1°E

Metropolitan cities of the People's Republic of China Municipalities and National central cities Regional central cities Special administrative regions Sub-provincial cities (not included above) Separate state-planning cities (not included above) Provincial capitals (not included above) Autonomous regional capitals Comparatively large cities (not included above) Special economic zone cities (not included above) Coastal development cities (not included above) XPCC / Bingtuan cities State-level new areas Pudong New Area (Shanghai) · Binhai New Area (Tianjin) · Liangjiang New Area (Chongqing) · Zhoushan Archipelago New Area (Zhoushan)Provincial capitals of the People's Republic of China Changchun, Jilin · Changsha, Hunan · Chengdu, Sichuan · Fuzhou, Fujian · Guangzhou, Guangdong · Guiyang, Guizhou · Haikou, Hainan · Hangzhou, Zhejiang · Harbin, Heilongjiang · Hefei, Anhui · Hohhot, Inner Mongolia · Jinan, Shandong · Kunming, Yunnan · Lanzhou, Gansu · Lhasa, Tibet · Nanchang, Jiangxi · Nanjing, Jiangsu · Nanning, Guangxi · Shenyang, Liaoning · Shijiazhuang, Hebei · Taiyuan, Shanxi · Ürümqi, Xinjiang · Wuhan, Hubei · Xi'an, Shaanxi · Xining, Qinghai · Yinchuan, Ningxia · Zhengzhou, Henan

Dongcheng District (Beijing) · Yuzhong District (Chongqing) · Huangpu District (Shanghai) · Heping District (Tianjin)

Lhünzhub · Damxung · Nyêmo · Qüxü · Doilungdêqên · Dagzê · Maizhokunggar · Chengguan District

Towns and villages Monasteries

and palacesArchitecture of Lhasa · Lingkhor · Potala Palace · Norbulingka · Jokhang Temple · Tsomon Ling · Ganden Monastery · · Kundeling Monastery · Nechung · Nyethang Drolma Lhakhang Temple · Yangpachen Monastery · · Drepung Monastery · Ramoche Temple · Reting Monastery · Sanga Monastery · Yerpa

Sera Monastery: · Chupzang Nunnery · Drakri Hermitage · Garu Nunnery · Jokpo Hermitage · Keutsang Hermitage · Keutsang East Hermitage · Keutsang West Hermitage · Khardo Hermitage · Negodong Nunnery · Nenang Nunnery · Pabongkha Hermitage · Panglung Hermitage · Purbuchok Hermitage · Rakhadrak Hermitage · Sera Chöding Hermitage · Sera Gönpasar Hermitage · Sera Utsé Hermitage · Takten Hermitage · Trashi Chöling HermitageOther landmarks Banak Shöl Hotel · Barkhor · Chokpori · Drapchi Prison · Lhasa Brewery · Lhasa Hotel · Lhasa Zhol Pillar · Tibet Museum · Tibet University · Tromzikhang · Nyang bran · Hutoushan ReservoirTransport Lhasa Airport · Damxung Railway Station · Lhasa Railway Station · Lhasa West Railway Station · Wumatang railway station · Yangbajain Railway Station · G109 · G318 · North Linkor RoadGovernment Doje Cezhug · Jigme Namgyal

Categories:- Populated places in Tibet

- Holy cities

- Lhasa

- Lhasa Prefecture

- Prefectures of Tibet

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.