- Sodium nitrite

-

Sodium nitrite

Identifiers CAS number 7632-00-0

PubChem 24269 ChemSpider 22689

UNII M0KG633D4F

EC number 231-555-9 UN number 1500 ChEMBL CHEMBL93268

RTECS number RA1225000 ATC code V03 Jmol-3D images Image 1 - N(=O)[O-].[Na+]

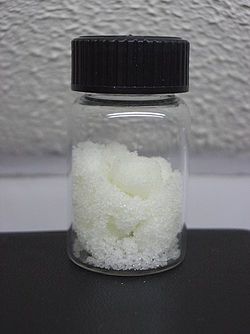

Properties Molecular formula NaNO2 Molar mass 68.9953 g/mol Appearance white or slightly yellowish solid Density 2.168 g/cm3 Melting point 271 °C decomp.

Solubility in water 82 g/100 ml (20 °C) Structure Crystal structure Trigonal Hazards MSDS External MSDS EU Index 007-010-00-4 EU classification Oxidant (O)

Toxic (T)

Dangerous for the environment (N)R-phrases R8, R25, R50 S-phrases (S1/2), S45, S61 NFPA 704 Autoignition

temperature489 °C LD50 180 mg/kg (rats, oral) Related compounds Other anions Lithium nitrite

Sodium nitrateOther cations Potassium nitrite

Ammonium nitrite nitrite (verify) (what is:

nitrite (verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Sodium nitrite is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula NaNO2. It is a white to slight yellowish crystalline powder that is very soluble in water and is hygroscopic. It is a useful precursor to a variety of organic compounds, such as pharmaceuticals, dyes, and pesticides, but it is probably best know as a food additive to prevent botulism.

Contents

Production

The salt is prepared by treating sodium hydroxide with mixtures of nitrogen dioxide and nitric oxide:

- 2 NaOH + NO2 + NO → 2 NaNO2 + H2O

The conversion is sensitive to the presence of oxygen, which can lead to varying amounts of sodium nitrate.

In former times, sodium nitrite was prepared by reduction of sodium nitrate with various metals.[1]

Chemical reactions

In the laboratory, sodium nitrite can be used to destroy excess sodium azide.[2][3]

- 2 NaN3 + 2 Na NO2 + 2 H+ → 3 N2 + 2 NO + 2 Na+ + 2 H2O

At high temperatures, sodium nitrite decomposes sodium oxide, nitrogen(II) oxide and oxygen.

Uses

Industrial chemistry

The main use of sodium nitrite is for the industrial production of organonitrogen compounds. It is a reagent for conversion of amines into diazo compounds, which are key precursors to many dyes, such as diazo dyes. Nitroso compounds are produced from nitrites. These are used in the rubber industry.[1]

Other applications include uses in photography. It may also be used as an electrolyte in electrochemical grinding manufacturing processes, typically diluted to about 10% concentration in water. It is used in a variety of metallurgical applications, for phosphatizing and detinning. Sodium nitrite also has been used in human and veterinary medicine as a vasodilator, a bronchodilator, and an antidote for cyanide poisoning (see Cyanide#Antidote).

Food additive

As a food additive, it prevents growth of Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium which causes botulism. It also alters the color of preserved fish and meats. In the European Union it may be used only as a mixture with salt containing at most 0.6% sodium nitrite. It has the E number E250. Potassium nitrite (E249) is used in the same way. It is approved for usage in the EU,[4] USA[5] and Australia and New Zealand.[6]

Toxicity

While this chemical will prevent the growth of bacteria, it can be toxic in high amounts for animals, including humans. Sodium nitrite's LD50 in rats is 180 mg/kg and its human LDLo is 71 mg/kg, meaning a 65 kg person would likely have to consume at least 4.615 g to result in death.[7] To prevent toxicity, sodium nitrite (blended with salt) sold as a food additive is dyed bright pink to avoid mistaking it for plain salt or sugar.Nitrites are a normal part of human diet, found in most vegetables.[8][9][10] Spinach and lettuce can have as high as 2500 mg/kg, curly kale (302.0 mg/kg) and green cauliflower (61.0 mg/kg), to a low of 13 mg/kg for asparagus. Nitrite levels in 34 vegetable samples, including different varieties of cabbage, lettuce, spinach, parsley and turnips ranged between 1.1 and 57 mg/kg, e.g. white cauliflower (3.49 mg/kg) and green cauliflower (1.47 mg/kg).[11][8] Boiling vegetables lowers nitrate but not nitrite.[8] Fresh meat contains 0.4-0.5 mg/kg nitrite and 4–7 mg/kg of nitrate (10–30 mg/kg nitrate in cured meats).[10] The presence of nitrite in animal tissue is a consequence of metabolism of nitric oxide, an important neurotransmitter.[12] Nitric oxide can be created de novo from nitric oxide synthase utilizing arginine or from ingested nitrate or nitrite.[13] Most research on negative effects of nitrites on humans predates discovery of nitric oxide's importance to human metabolism and human endogenous metabolism of nitrite.

Humane toxin for feral hogs/wild boar control

Because of sodium nitrite's high level of toxicity to swine (Sus scrofa) it is now being developed in Australia to contol feral pigs and wild boar.[14][15]. The sodium nitrite induces methemoglobinemia in swine, i.e., it reduces the amount of oxygen that is released from hemoglobin), so the animal will feel faint and pass out, and then die in a humane manner after first being rendered unconscious[16].

Nitrosamines

A principal concern about sodium nitrite is the formation of carcinogenic nitrosamines in meats containing sodium nitrite when meat is charred or overcooked. Such carcinogenic nitrosamines can be formed from the reaction of nitrite with secondary amines under acidic conditions (such as occurs in the human stomach) as well as during the curing process used to preserve meats. Dietary sources of nitrosamines include US cured meats preserved with sodium nitrite as well as the dried salted fish eaten in Japan. In the 1920s, a significant change in US meat curing practices resulted in a 69% decrease in average nitrite content. This event preceded the beginning of a dramatic decline in gastric cancer mortality.[17] About 1970, it was found that ascorbic acid (vitamin C), an antioxidant, inhibits nitrosamine formation.[18] Consequently, the addition of at least 550 ppm of ascorbic acid is required in meats manufactured in the United States. Manufacturers sometimes instead use erythorbic acid, a cheaper but equally effective isomer of ascorbic acid. Additionally, manufacturers may include alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) to further inhibit nitrosamine production. Alpha-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, and erythorbic acid all inhibit nitrosamine production by their oxidation-reduction properties. Ascorbic acid, for example, forms dehydroascorbic acid when oxidized, which when in the presence of nitrous anhydride, a potent nitrosating agent formed from sodium nitrate, reduces the nitrous anhydride into the nitric oxide gas.[19] Note that Nitrous Anhydride does not exist[20] in vitro.

Sodium nitrite consumption has also been linked to the triggering of migraines in individuals who already suffer from them.[21]

One study has found a correlation between highly frequent ingestion of meats cured with pink salt and the COPD form of lung disease. The study's researchers suggest that the high amount of nitrites in the meats was responsible; however, the team did not prove the nitrite theory. Additionally, the study does not prove that nitrites or cured meat caused higher rates of COPD, merely a link. The researchers did adjust for many of COPD's risk factors, but they commented they cannot rule out all possible unmeasurable causes or risks for COPD.[22][23]

Mechanism of action

Carcinogenic nitrosamines are formed when amines that occur naturally in food react with sodium nitrite found in cured meat products.

- R2NH (amines) + NaNO2 (sodium nitrite) → R2N-N=O (nitrosamine)

In the presence of acid (such as in the stomach) or heat (such as via cooking), nitrosamines are converted to diazonium ions.

- R2N-N=O (nitrosamine) + (acid or heat) → R-N2+ (diazonium ion)

Certain nitrosamines such as N-nitrosodimethylamine[24] and N-nitrosopyrrolidine[25] form carbocations that react with biological nucleophiles (such as DNA or an enzyme) in the cell.

- R-N2+ (diazonium ion) → R+ (carbocation) + N2 (leaving group) + :Nu (biological nucleophiles) → R-Nu

If this nucleophilic substitution reaction occurs at a crucial site in a biomolecule, it can disrupt normal cell functioning leading to cancer or cell death.

References

- ^ a b Wolfgang Laue, Michael Thiemann, Erich Scheibler, Karl Wilhelm Wiegand “Nitrates and Nitrites” in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_265. Article Online Posting Date: June 15, 2000

- ^ "Sodium Azide". Hazardous Waste Management. Northeastern University. March 2003. http://www.ehs.neu.edu/hazardous_waste/fact_sheets/sodium_azide/.

- ^ Committee on Prudent Practices for Handling, Storage, and Disposal of Chemicals in Laboratories, Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications, National Research Council. (1995). Prudent practices in the laboratory: handling and disposal of chemicals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN 0309052297. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=4911&page=165.

- ^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". http://www.food.gov.uk/safereating/chemsafe/additivesbranch/enumberlist. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration: "Listing of Food Additives Status Part II". http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodIngredientsPackaging/FoodAdditives/ucm191033.htm#ftnT. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2011C00827. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ http://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/SO/sodium_nitrite.html

- ^ a b c Leszczyńska, Teresa; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, Agnieszka; Cieślik, Ewa; Sikora, ElżBieta; Pisulewski, Paweł M. (2009). "Effects of some processing methods on nitrate and nitrite changes in cruciferous vegetables". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 22 (4): 315. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2008.10.025.

- ^ http://www.wholesomebabyfood.com/nitratearticle.htm

- ^ a b Dennis, M J; Wilson, L A (2003). "NITRATES AND NITRITES". Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. pp. 4136. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227055-X/00830-0. ISBN 9780122270550.

- ^ Correia, Manuela; Barroso, ÂNgela; Barroso, M. FáTima; Soares, DéBora; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Delerue-Matos, Cristina (2010). "Contribution of different vegetable types to exogenous nitrate and nitrite exposure". Food Chemistry 120 (4): 960. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.030.

- ^ Meulemans, A.; Delsenne, F. (1994). "Measurement of nitrite and nitrate levels in biological samples by capillary electrophoresis". Journal of Chromatography B 660 (2): 401. doi:10.1016/0378-4347(94)00310-6.

- ^ Southan, G; Srinivasan, A (1998). "Nitrogen Oxides and Hydroxyguanidines: Formation of Donors of Nitric and Nitrous Oxides and Possible Relevance to Nitrous Oxide Formation by Nitric Oxide Synthase". Nitric Oxide 2 (4): 270–86. doi:10.1006/niox.1998.0187. PMID 9851368.

- ^ Lapidge, Steven; J. Wishart, M. Smith, L. Staples (2009). "Is America Ready for a Humane Feral Pig Toxicant?". Proceedings of the 13th Wildlife Damage Management Conference: 49–59.

- ^ Cowled, BD; SJ Lapidge, S. Humphrys, L Staples (2008). "Nitrite Salts as Poisons in Baits for Omnivores". International Patent WO/2008/104028. http://www.wipo.int/patentscope/search/en/WO2008104028.

- ^ S. Porter & T. Kuchel (2010). Assessing the humaness and efficacy of a new feral pig bait in domestic pigs. Study PC0409. Canberra, South Australia: Veterinary Services Division, Institue of Medical and Veterinary Science. pp. 11. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/publications/pubs/pigs-imvs-report.pdf.

- ^ "The epidemiological enigma of gastric cancer rates in the US: was grandmother's sausage the cause?", International Journal of Epidemiology (2000) accessdate 2000-08-01

- ^ C.W. Mackerness, S.A. Leach, M.H. Thompson and M.J. Hill (1989). "The inhibition of bacterially mediated N-nitrosation by vitamin C: relevance to the inhibition of endogenous N-nitrosation in the achlorhydric stomach". Carcinogenesis 10 (2): 397–9. doi:10.1093/carcin/10.2.397. PMID 2492212. http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/10/2/397.

- ^ http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/f-w00/nitrosamine.html Nitrosamines and Cancer by Richard A. Scanlan, Ph.D.

- ^ Williams, D (2004). "Reagents effecting nitrosation". Nitrosation Reactions and the Chemistry of Nitric Oxide. pp. 1. doi:10.1016/B978-044451721-0/50002-5. ISBN 978-0-44-451721-0.

- ^ "Heading Off Migraine Pain". FDA Consumer magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 1998. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps1609/www.fda.gov/fdac/features/1998/398_pain.html.

- ^ Miranda Hitti (17 April 2007). "Study: Cured Meats, COPD May Be Linked". WebMD Medical News. http://www.webmd.com/news/20070417/study-copd-cured-meats-may-be-linked.

- ^ Jiang, R.; Paik, D. C.; Hankinson, J. L.; Barr, R. G. (2007). "Cured Meat Consumption, Lung Function, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among United States Adults". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 175 (8): 798–804. doi:10.1164/rccm.200607-969OC. PMC 1899290. PMID 17255565. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1899290.

- ^ Najm, Issam; Trussell, R. Rhodes (February 2001). "NDMA Formation in Water and Wastewater". Journal AWWA 93 (2): 92–99.

- ^ Donald D. Bills, Kjell I. Hildrum, Richard A. Scanlan, Leonard M. Libbey (May 1973). "Potential precursors of N-nitrosopyrrolidine in bacon and other fried foods". J. Agric. Food Chem. 21 (5): 876–7. doi:10.1021/jf60189a029. PMID 4739004.

External links

- ATSDR - Case Studies in Environmental Medicine - Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (public domain)

- International Chemical Safety Card 1120.

- European Chemicals Bureau.

- National Center for Home Food Preservation Nitrates and Nitrites.

- TR-495: Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Sodium Nitrite (CAS NO. 7632-00-0) Drinking Water Studies in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice.

- FOX news article concerning carcinogicity and hot dogs

- Nitrite in Meat

Antidotes (V03AB) Nervous system Barbiturate overdoseBemegride • EthamivanBenzodiazepine overdoseGHB overdoseCardiovascular Other Paracetamol toxicity (Acetaminophen)nitrite (Amyl nitrite, Sodium nitrite#) • Sodium thiosulfate# • 4-Dimethylaminophenol • HydroxocobalaminOtherPrednisolone/promethazine • oxidizing agent (potassium permanganate) • iodine-131 (Potassium iodide) • Methylthioninium chloride#Emetic Sodium compounds NaAlO2 · NaBH3(CN) · NaBH4 · NaBr · NaBrO3 · NaCH3COO · NaCN · NaC6H5CO2 · NaC6H4(OH)CO2 · NaCl · NaClO · NaClO2 · NaClO3 · NaClO4 · NaF · NaH · NaHCO3 · NaHSO3 · NaHSO4 · NaI · NaIO3 · NaIO4 · NaMnO4 · NaNH2 · NaNO2 · NaNO3 · NaN3 · NaOH · NaO2 · NaPO2H2 · NaReO4 · NaSCN · NaSH · NaTcO4 · NaVO3 · Na2CO3 · Na2C2O4 · Na2CrO4 · Na2Cr2O7 · Na2MnO4 · Na2MoO4 · Na2O · Na2O2 · Na2O(UO3)2 · Na2S · Na2SO3 · Na2SO4 · Na2S2O3 · Na2S2O4 · Na2S2O5 · Na2S2O6 · Na2S2O7 · Na2S2O8 · Na2Se · Na2SeO3 · Na2SeO4 · Na2SiO3 · Na2Te · Na2TeO3 · Na2Ti3O7 · Na2U2O7 · NaWO4 · Na2Zn(OH)4 · Na3N · Na3P · Na3VO4 · Na4Fe(CN)6 · Na5P3O10 · NaBiO3

Categories:- Sodium compounds

- Nitrites

- Color fixers

- Curing agents

- Corrosion inhibitors

- Food additives

- Garde manger

- Antidotes

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- Oxidizing agents

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.