- History of video games

-

Part of a series on: History of video games General- Golden age of video arcade games

- History of video games

- North American video game crash of 1983

- History of massively multiplayer online games

- History of online games

- History of role-playing video games

Lists- Early history of video games

- First video game

- List of video games in development

- List of years in video games

- Timeline of video arcade game history

The history of video games goes as far back as the 1940s, when in 1947 Thomas T. Goldsmith, Jr. and Estle Ray Mann filed a United States patent request for an invention they described as a "cathode ray tube amusement device." Video gaming would not reach mainstream popularity until the 1970s and 80s, when arcade and computer games and the first gaming consoles were introduced to the general public. Since then, video gaming has become a popular form of entertainment and a part of modern culture in the developed world. There are considered to be currently seven generations of video game consoles, with the seventh being ongoing and the most recent.

Contents

- 1 Early history

- 2 1970s

- 3 1980s

- 4 1990s

- 5 2000s

- 6 2010s

- 7 See also

- 8 Notes

- 9 References

- 10 Further reading

- 11 External links

Early history

Main article: First video gameOn January 25, 1947, Thomas T. Goldsmith, Jr. and Estle Ray Mann filed a United States patent request for an invention they described as a "cathode ray tube amusement device".[1] This patent, which the United States Patent Office issued on December 14, 1948, details a machine in which a person uses knobs and buttons to manipulate a cathode ray tube beam to simulate firing at "airplane" targets. A printed overlay on the CRT screen helps to define the playing field.

In 1949–1950, Charley Adama created a "Bouncing Ball" program for MIT's Whirlwind computer.[2] While the program was not yet interactive, it was a precursor to games soon to come.

In February 1951, Christopher Strachey tried to run a draughts program he had written for the NPL Pilot ACE. The program exceeded the memory capacity of the machine and Strachey recoded his program for a machine at Manchester with a larger memory capacity by October.

Also in 1951, while developing television technologies for New York based electronics company Loral, inventor Ralph Baer came up with the idea of using the lights and patterns he used in his work as more than just calibration equipment. He realized that by giving an audience the ability to manipulate what was projected on their television sets, their role changed from passive observing to interactive manipulation. When he took this idea to his supervisor, it was quickly squashed because the company was already behind schedule.[3]

OXO, a graphical version tic-tac-toe, was created by A.S. Douglas in 1952 at the University of Cambridge, in order to demonstrate his thesis on human-computer interaction. It was developed on the EDSAC computer, which uses a cathode ray tube as a visual display to display memory contents. The player competes against the computer.

In 1958 William Higinbotham created a game using an oscilloscope and analog computer.[4] Titled Tennis for Two, it was used to entertain visitors of the Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York.[5] Tennis for Two showed a simplified tennis court from the side, featuring a gravity-controlled ball that needed to be played over the "net," unlike its successor—Pong. The game was played with two box-shaped controllers, both equipped with a knob for trajectory and a button for hitting the ball.[4] Tennis for Two was exhibited for two seasons before it was dismantled in 1959.[6]

Late 1950s–1969

Spacewar! is credited as the first widely available and influential computer game.

Spacewar! is credited as the first widely available and influential computer game.

The majority of early computer games ran on universities' mainframe computers in the United States and were developed by individuals as a hobby. The limited accessibility of early computer hardware meant that these games were small in number and forgotten by posterity.[citation needed]

In 1959–1961, a collection of interactive graphical programs were created on the TX-0 machine at MIT:

- Mouse in the Maze: allowed players to place maze walls, bits of cheese, and, in some versions, martinis using a light pen. One could then release the mouse and watch it traverse the maze to find the goodies.[7]

- HAX: By adjusting two switches on the console, various graphical displays and sounds could be made.

- Tic-Tac-Toe: Using the light pen, the user could play a simple game of tic-tac-toe against the computer.

In 1961, a group of students at MIT, including Steve Russell, programmed a game titled Spacewar! on the DEC PDP-1, a new computer at the time.[8] The game pitted two human players against each other, each controlling a spacecraft capable of firing missiles, while a star in the center of the screen created a large hazard for the crafts. The game was eventually distributed with new DEC computers and traded throughout the then-primitive Internet. Spacewar! is credited as the first influential computer game.

In 1966, Ralph Baer engaged co-worker Bill Harrison in the project, where they both worked at military electronics contractor Sanders Associates in Nashua, NH. They created a simple video game named Chase, the first to display on a standard television set. With the assistance of Baer, Bill Harrison created the light gun. Baer and Harrison were joined by Bill Rusch in 1967, an MIT graduate (MSEE) who was subsequently awarded several patents for the TV gaming apparatus (US Patents 3,659,284, 3,778,058, etc.). Development continued, and in 1968 a prototype was completed that could run several different games such as table tennis and target shooting. After months of secretive labouring between official projects, the team was able to bring an example with true promise to Sanders' R & D department. By 1969, Sanders was showing off the world’s first home video game console to manufacturers.[3]

In 1969, AT&T computer programmer Ken Thompson wrote a video game called Space Travel for the Multics operating system. This game simulated various bodies of the solar system and their movements and the player could attempt to land a spacecraft on them. AT&T pulled out of the MULTICS project, and Thompson ported the game to Fortran code running on the GECOS operating system of the General Electric GE 635 mainframe computer. Runs on this system cost about $75 per hour, and Thompson looked for a smaller, less expensive computer to use. He found an underused PDP-7, and he and Dennis Ritchie started porting the game to PDP-7 assembly language. In the process of learning to develop software for the machine, the development process of the Unix operating system began, and Space Travel has been called the first UNIX application.[9]

1970s

Early arcade video games (1971–1977)

See also: Arcade gameIn September 1971, the Galaxy Game was installed at a student union at Stanford University. Based on Spacewar!, this was the first coin-operated video game. Only one was built, using a DEC PDP-11 and vector display terminals. In 1972 it was expanded to be able to handle four to eight consoles.

Also in 1971, Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney created a coin-operated arcade version of Spacewar! and called it Computer Space. Nutting Associates bought the game and manufactured 1,500 Computer Space machines, with the release taking place in November 1971. The game was unsuccessful due to its steep learning curve, but was a landmark as the first mass-produced video game and the first offered for commercial sale.

Bushnell and Dabney founded Atari, Inc. in 1972, before releasing their next game: Pong. Pong was the first arcade video game with widespread success. The game is loosely based on table tennis: a ball is "served" from the center of the court and as the ball moves towards their side of the court each player must maneuver their paddle to hit the ball back to their opponent. Atari sold over 19,000 Pong machines,[10] creating many imitators.

First generation consoles (1972–1977)

Main article: History of video game consoles (first generation)The first home 'console' system was developed by Ralph Baer and his associates. Development began in 1966 and a working prototype was completed by 1968 (called the "Brown Box") for demonstration to various potential licensees, including GE, Sylvania, RCA, Philco, and Sears, with Magnavox eventually licensing the technology to produce the world's first home video game console.[11][12] The system was released in the USA in 1972 by Magnavox, called the Magnavox Odyssey. The Odyssey used cartridges that mainly consisted of jumpers that enabled/disabled various switches inside the unit, altering the circuit logic (as opposed to later video game systems that used programmable cartridges). This provided the ability to play several different games using the same system, along with plastic sheet overlays taped to the television that added color, play-fields, and various graphics to 'interact' with using the electronic images generated by the system.[13] A major marketing push, featuring TV ads starring Frank Sinatra, helped Magnavox sell about 100,000 Odysseys that first year.[3]

Philips bought Magnavox and released a different game in Europe using the Odyssey brand in 1974 and an evolved game that Magnavox had been developing for the US market. Over its production span, the Odyssey system achieved sales of 2 million units.

Mainframe computers

University mainframe game development blossomed in the early 1970s. There is little record of all but the most popular games, as they were not marketed or regarded as a serious endeavor. The people–generally students–writing these games often were doing so illicitly by making questionable use of very expensive computing resources, and thus were not anxious to let very many people know of their endeavors. There were, however, at least two notable distribution paths for student game designers of this time:

- The PLATO system was an educational computing environment designed at the University of Illinois and which ran on mainframes made by Control Data Corporation. Games were often exchanged between different PLATO systems.

- DECUS was the user group for computers made by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). It distributed programs–including games–that would run on the various types of DEC computers.

A number of noteworthy games were also written for Hewlett-Packard minicomputers such as the HP2000.

Highlights of this period, in approximate chronological order, include:

- 1971: Don Daglow wrote the first computer baseball game on a DEC PDP-10 mainframe at Pomona College. Players could manage individual games or simulate an entire season. Daglow went on to team with programmer Eddie Dombrower to design Earl Weaver Baseball, published by Electronic Arts in 1987.

- 1971: Star Trek was created (probably by Mike Mayfield) on a Sigma 7 minicomputer at University of California. This is the best-known and most widely played of the 1970s Star Trek titles, and was played on a series of small "maps" of galactic sectors printed on paper or on the screen. It was the first major game to be ported across hardware platforms by students. Daglow also wrote a popular Star Trek game for the PDP-10 during 1970–1972, which presented the action as a script spoken by the TV program's characters. A number of other Star Trek themed games were also available via PLATO and DECUS throughout the decade.

- 1972: Gregory Yob wrote the hide-and-seek game Hunt the Wumpus for the PDP-10, which could be considered the first text adventure. Yob wrote it in reaction to existing hide-and-seek games such as Hurkle, Mugwump, and Snark.

- 1974: Both Maze War (on the Imlac PDS-1 at the NASA Ames Research Center in California) and Spasim (on PLATO) appeared, pioneering examples of early multi-player 3D first-person shooters.

- 1974: Brand Fortner and others developed Airfight as an educational flight simulator. To make it more interesting, all players shared an airspace flying their choice of military jets, loaded with selected weapons and fuel and to fulfill their desire to shoot down other players' aircraft. Despite mediocre graphics and slow screen refresh, it became a popular game on the PLATO system. Airfight was the inspiration for what became the Microsoft Flight Simulator.

- 1975: William Crowther wrote the first modern text adventure game, Adventure (originally called ADVENT, and later Colossal Cave). It was programmed in Fortran for the PDP-10. The player controls the game through simple sentence-like text commands and receives descriptive text as output. The game was later re-created by students on PLATO, so it is one of the few titles that became part of both the PLATO and DEC traditions.

- 1975: By 1975, many universities had discarded these terminals for CRT screens, which could display thirty lines of text in a few seconds instead of the minute or more that printing on paper required. This led to the development of a series of games that drew "graphics" on the screen. The CRTs replaced the typical teleprinters or line printers that output at speeds ranging from 10 to 30 characters per second.

- 1975: Daglow, then a student at Claremont Graduate University, wrote the first Computer role-playing game on PDP-10 mainframes: Dungeon. The game was an unlicensed implementation of the new role playing game Dungeons & Dragons. Although displayed in text, it was the first game to use line of sight graphics, as the top-down dungeon maps showing the areas that the party had seen or could see took into consideration factors such as light or darkness and the differences in vision between species.

- 1975: At about the same time, the RPG dnd, also based on Dungeons and Dragons first appeared on PLATO system CDC computers. For players in these schools dnd, not Dungeon, was the first computer role-playing game.

- 1976: The earliest role-playing video games to use elements from Dungeons and Dragons are Telengard, written in 1976, and Zork (later renamed Dungeon), written in 1977.[14][15]

- 1977: Kelton Flinn and John Taylor create the first version of Air, a text air combat game that foreshadowed their later work creating the first-ever graphical online multi-player game, Air Warrior. They would found the first successful online game company, Kesmai, now part of Electronic Arts. As Flinn has said: "If Air Warrior was a primate swinging in the trees, AIR was the text-based amoeba crawling on the ocean floor. But it was quasi-real time, multi-player, and attempted to render 3-D on the terminal using ASCII graphics. It was an acquired taste."[citation needed]

- 1977: The writing of the original Zork was started by Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, Tim Anderson, and Bruce Daniels. Unlike Crowther, Daglow and Yob, the Zork team recognized the potential to move these games to the new personal computers and they founded text adventure publisher Infocom in 1979. The company was later sold to Activision.

- 1978: Multi-User Dungeon, the first MUD, was created by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle, beginning the heritage that culminates with today's MMORPGs.

- 1980: Michael Toy, Glenn Wichman and Ken Arnold released Rogue on BSD Unix after two years of work, inspiring many roguelike games ever since. Like Dungeon on the PDP-10 and dnd on PLATO, Rogue displayed dungeon maps using text characters. Unlike those games, however, the dungeon was randomly generated for each play session, so the path to treasure and the enemies who protected it were different for each game. As the Zork team had done, Rogue was adapted for home computers and became a commercial product.

Video game crash of 1977

In 1977, manufacturers of older, obsolete consoles and Pong clones sold their systems at a loss to clear stock, creating a glut in the market,[16] and causing Fairchild and RCA to abandon their game consoles. Only Atari and Magnavox remained in the home console market, despite suffering losses in 1977 and 1978.[17]

The crash was largely caused by the significant number of Pong clones that flooded both the arcade and home markets. The crash eventually came to an end with the success of Taito's Space Invaders, released in 1978, sparking a renaissance for the video game industry and paving the way for the golden age of video arcade games.[16] Soon after, Space Invaders was licensed for the Atari VCS (later known as Atari 2600), becoming the first "killer app" and quadrupling the console's sales.[18] This helped Atari recover from their earlier losses.[17] The success of the Atari 2600 in turn revived the home video game market, up until the North American video game crash of 1983.[19]

Second generation consoles (1977–1983)

Main article: History of video game consoles (second generation)In the earliest consoles, the computer code for one or more games was hardcoded into microchips using discrete logic, and no additional games could ever be added. By the mid-1970s video games were found on cartridges, starting in 1976 with the release of the Fairchild 'Video Entertainment System (VES). Programs were burned onto ROM chips that were mounted inside plastic cartridge casings that could be plugged into slots on the console. When the cartridges were plugged in, the general-purpose microprocessors in the consoles read the cartridge memory and executed whatever program was stored there. Rather than being confined to a small selection of games included in the game system, consumers could now amass libraries of game cartridges. However video game production was still a niche skill. Warren Robinett, the famous programmer of the game Adventure, spoke on developing games "in those old far-off days, each game for the 2600 was done entirely by one person, the programmer, who conceived the game concept, wrote the program, did the graphics—drawn first on graph paper and converted by hand to hexadecimal—and did the sounds."[20]

Three machines dominated the second generation of consoles in North America, far outselling their rivals:

- The Video Computer System (VCS) ROM cartridge-based console, later renamed the Atari 2600, was released in 1977 by Atari. Nine games were designed and released for the holiday season. While the console had a slow start, its port of the arcade game Space Invaders would become the first "killer app" and quadruple the console's sales.[18] Soon after, the Atari 2600 would quickly become the most popular of all the early consoles prior to the North American video game crash of 1983.

- The Intellivision, introduced by Mattel in 1980. Though chronologically part of what is called the "8-bit era", the Intellivision had a unique processor with instructions that were 10 bits wide (allowing more instruction variety and potential speed), and registers 16 bits wide. The system, which featured graphics superior to the older Atari 2600, rocketed to popularity.

- The ColecoVision, an even more powerful machine, appeared in 1982. Its sales also took off, but the presence of three major consoles in the marketplace and a glut of poor quality games began to overcrowd retail shelves and erode consumers' interest in video games. Within a year this overcrowded market would crash.

In 1979, Activision was created by disgruntled former Atari programmers "who realized that the games they had anonymously programmed on their $20K salaries were responsible for 60 percent of the company's $100 million in cartridge sales for one year".[21] It was the first third-party developer of video games. By 1982, approximately 8 million American homes owned a video game console, and the home video game industry was generating an annual revenue of $3.8 billion, which was nearly half the $8 billion revenue in quarters generated from the arcade video game industry at the time.[22]

Golden age of video arcade games (1978–1986)

Main article: Golden age of video arcade gamesThe arcade game industry entered its golden age in 1978 with the release of Space Invaders by Taito, a success that inspired dozens of manufacturers to enter the market.[16][23] The game inspired arcade machines to become prevalent in mainstream locations such as shopping malls, traditional storefronts, restaurants and convenience stores during the golden age.[24] Space Invaders would go on to sell over 360,000 arcade cabinets worldwide,[25] and by 1982, generate a revenue of $2 billion in quarters,[26] equivalent to $4.6 billion in 2011.[27] In 1979, Namco's Galaxian sold over 40,000 cabinets,[28] and Atari released Asteroids which sold over 70,000 cabinets.[29]

The total sales of arcade video game machines in North America increased significantly during this period, from $50 million in 1978 to $900 million by 1981,[30] with the arcade video game industry's revenue in North America reaching nearly $1 billion in quarters by the end of the 1970s, a figure that would triple to $2.8 billion by 1980.[31] Color arcade games also became more popular in 1979 and 1980 with the arrival of titles such as Pac-Man, which would go on to sell over 350,000 cabinets,[32] and within a year, generate a revenue of more than $1 billion in quarters;[33] in total, Pac-Man is estimated to have grossed over 10 billion quarters ($2.5 billion) during the 20th century,[33][34] equivalent to over $3.4 billion in 2011.[27]

By 1981, the arcade video game industry was generating an annual revenue of $5 billion in North America,[16][35] equivalent to $12.3 billion in 2011.[27] In 1982, the arcade video game industry reached its peak, generating $8 billion in quarters,[22] equivalent to over $18.5 billion in 2011,[27] surpassing the annual gross revenue of both pop music ($4 billion) and Hollywood films ($3 billion) combined at that time.[22] This was also nearly twice as much revenue as the $3.8 billion generated by the home video game industry that same year; both the arcade and home markets combined add up to a total revenue of $11.8 billion for the video game industry in 1982,[22] equivalent to over $27.3 billion in 2011.[27] The arcade video game industry would continue to generate an annual revenue of $5 billion in quarters through to 1985.[36]

Home computer games (late 1970s–early 1980s)

See also: Personal computer gameWhile the fruit of retail development in early video games appeared mainly in video arcades and home consoles, home computers began appearing in the late 1970s and were rapidly evolving in the 80s, allowing their owners to program simple games. Hobbyist groups for the new computers soon formed and personal computer game software followed.

Soon many of these games—at first clones of mainframe classics such as Star Trek, and then later ports or clones of popular arcade games such as Space Invaders, Frogger,[37] Pac-Man (see Pac-Man clones)[38] and Donkey Kong[39]—were being distributed through a variety of channels, such as printing the game’s source code in books (such as David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games), magazines (Creative Computing), and newsletters, which allowed users to type in the code for themselves. Early game designers like Crowther, Daglow and Yob would find the computer code for their games—which they had never thought to copyright—published in books and magazines, with their names removed from the listings. Early home computers from Apple, Commodore, Tandy and others had many games that people typed in.

Games were also distributed by the physical mailing and selling of floppy disks, cassette tapes, and ROM cartridges. Soon a small cottage industry was formed, with amateur programmers selling disks in plastic bags put on the shelves of local shops or sent through the mail. Richard Garriott distributed several copies of his 1980 computer role-playing game Akalabeth: World of Doom in plastic bags before the game was published.

1980s

Main article: 1980s in video gamingThe computer gaming industry experienced its first major growing pains in the early 1980s as publishing houses appeared, with many honest businesses—occasionally surviving at least 20 years, such as Electronic Arts—alongside fly-by-night operations that cheated the games' developers. While some early '80s games were simple clones of existing arcade titles, the relatively low publishing costs for personal computer games allowed for bold, unique games.

Genre innovation

See also: Golden age of video arcade gamesThe golden age of video arcade games reached its zenith in the 1980s. The age brought with it many technically innovative and genre-defining games developed and released in the first few years of the decade, including:

- Action adventure game: The Legend of Zelda (1986) helped establish the action-adventure genre, combining elements from different genres to create a compelling hybrid, including exploration, transport puzzles, adventure-style inventory puzzles, an action component, a monetary system, and simplified RPG-style level building without the experience points.[40] The game was also an early example of open world, nonlinear gameplay, and introduced innovations like battery backup saving.[41]

- Action role-playing games: Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu (1985) is considered the first full-fledged action role-playing game, with character stats and a large quest, with its action-based combat setting it apart from other RPGs. Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (1987), developed by Shigeru Miyamoto, further defined and popularized the emerging action RPG genre.

- Adventure games: Zork (1980) further popularized text adventure games in home computers and established developer Infocom’s dominance in the field. As these early computers often lacked graphical capabilities, text adventures proved successful. Mystery House (1980), Roberta Williams's game for the Apple II, was the first graphic adventure game on home computers. Graphics consisted entirely of static monochrome drawings, and the interface still used the typed commands of text adventures. It proved very popular at the time, and she and husband Ken went on to found Sierra On-Line, a major producer of adventure games. King's Quest (1984) was created by Sierra, laying the groundwork for the modern adventure game. It featured color graphics and a third-person perspective. An on-screen player character could be moved behind and in front of objects on a 2D background drawn in perspective, creating the illusion of pseudo-3D space. Commands were still entered via text. Maniac Mansion (1987) removed text entry from adventure games. LucasArts built the SCUMM system to allow a point-and-click interface. Sierra and other game companies quickly followed with their own mouse-driven games.

- Beat 'em up: Karateka (1984), with its pioneering rotoscoped animation, and Kung-Fu Master (1984), a Hong Kong cinema-inspired action game, laid the foundations for side-scrolling beat 'em ups with simple gameplay and multiple enemies.[42] Nekketsu Kōha Kunio-kun (1986), also released as Renegade, deviated from the martial arts themes of earlier game, introducing street brawling to the genre,[43] and set the standard for future beat 'em up games as it introduced the ability to move both horizontally and vertically.[44]

- Cinematic platformer: Prince of Persia (1989) was the first cinematic platformer.

- Computer role-playing games: Akalabeth (1980) was created in the same year as Rogue (1980); Akalabeth led to the creation of its spiritual sequel Ultima (1981). Its sequels were the inspiration for some of the first Japanese console role-playing games, alongside Wizardry (1981). The Bard's Tale (1985) by Interplay Entertainment is considered the first computer role-playing game to appeal to a wide audience that was not matched until Blizzard Entertainment's Diablo.[45]

- Console role-playing games: Dragon Warrior (1986), developed by Yuji Horii, was one of the earliest console role-playing games. With its anime-style graphics by Akira Toriyama (of Dragon Ball fame), Dragon Quest set itself apart from computer role-playing games. It spawned the Dragon Warrior {and later renamed Dragon Quest} franchise and served as the blueprint for the emerging console RPG genre,[46] inspiring the likes of Sega's Phantasy Star (1987) and Square's Final Fantasy (1987), which spawned its own successful Final Fantasy franchise and introduced the side-view turn-based battle system, with the player characters on the right and the enemies on the left, imitated by numerous later RPGs.[47] Megami Tensei (1987) and Phantasy Star (1987) broke with tradition, abandoning the medieval setting and sword and sorcery themes common in most RPGs, in favour of modern/futuristic settings and science fiction themes.

- Fighting games: Karate Champ (1984), Data East's action game, is credited with establishing and popularizing the one-on-one fighting game genre, and went on to influence Yie Ar Kung-Fu.[48] Konami's Yie Ar Kung Fu (1985), which expanded on Karate Champ by pitting the player against a variety of opponents, each with a unique appearance and fighting style.[48][49] Street Fighter (1987), developed by Capcom, introduced the use of special moves that could only be discovered by experimenting with the game controls.[50]

- Hack and slash: Golden Axe (1988) was acclaimed for its visceral hack and slash action and cooperative mode and was influential through its selection of multiple protagonists with distinct fighting styles.[51]

- Interactive movies: Astron Belt (1983), an early first-person shooter, was the first Laserdisc video game in development, featuring live-action FMV footage over which the player/enemy ships and laser fire are superimposed.[52] Dragon's Lair (1983) was the first Laserdisc video game to be released, beating Astron Belt to public release.[52]

- Platform games: Space Panic (1980) is sometimes credited as the first platform game,[53] with gameplay centered on climbing ladders between different floors. Donkey Kong (1981), an arcade game created by Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto, was the first game that allowed players to jump over obstacles and across gaps, making it the first true platformer.[54] This game also introduced Mario, an icon of the genre. Mario Bros. (1983), developed by Shigeru Miyamoto, offered two-player simultaneous cooperative play and laid the groundwork for two-player cooperative platformers.

- Scrolling platformers: Jump Bug (1981), Alpha Denshi's platform-shooter, was the first platform game to use scrolling graphics.[55] Taito's Jungle King (1982)[56] featured scrolling jump and run sequences that had players hopping over obstacles. Namco took the scrolling platformer a step further with Pac-Land (1984),[57] which was the first game to feature multi-layered parallax scrolling and closely resembled later scrolling platformers like Super Mario Bros. (1985) and Wonder Boy (1986).[58]

- Scrolling shooters: Defender (1980) established the use of side-scrolling in shoot 'em ups, offering horizontally extended levels. Scramble (1981) was the first side-scroller with multiple, distinct levels.[59] Jump Bug (1981) was a simple platform-shooter where players controlled a bouncing car. It featured levels that scrolled both horizontally and vertically.[60] Vanguard (1981) was both a horizontal and vertical scrolling shooter that allowed the player to shoot in four directions.[61] Xevious (1982) is frequently cited as the first vertical shooter and, although it was preceded by several other games featuring vertical scrolling, it was the most influential.[59] Moon Patrol (1982) introduced the parallax scrolling technique in computer graphics.[62] Gradius (1985) gave the player greater control over the choice of weaponry, thus introducing another element of strategy.[59] The game also introduced the need for the player to memorise levels in order to achieve any measure of success.[63] Thrust (1986) has the player maneuver a spaceship through a series of 2D cavernous landscapes, with the aim of recovering a pendulous pod, while counteracting gravity, inertia and avoiding or destroying enemy turrets.

- Isometric platformer: Congo Bongo (1983), developed by Sega, was the first isometric platformer.

- Isometric shooter: Zaxxon (1982) was the first game to use isometric projection.[59]

- Light gun shooter: The NES Zapper was the first mainstream light gun. The most successful lightgun game was Duck Hunt (1984), which came packaged with the NES.[64]

- Maze games: Pac-Man (1980) was the first game to achieve widespread popularity in mainstream culture and the first game character to be popular in his own right. 3D Monster Maze (1981) was the first 3D game for a home computer, while Dungeons of Daggorath (1982) added various weapons and monsters, sophisticated sound effects, and a "heartbeat" health monitor.

- Platform-adventure games: Metroid (1986) was the earliest game to fuse platform game fundamentals with elements of action-adventure games, alongside elements of RPGs. These elements include the ability to explore an area freely, with access to new areas controlled by either the gaining of new abilities or through the use of inventory items.[65] Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (1987) and Castlevania II: Simon's Quest (1987) are two other early examples of platform-adventure games.

- Racing games: Turbo (1981), by Sega, was the first racing game with a third-person perspective, rear-view format. Pole Position (1982), by Namco, used sprite-based, pseudo-3D graphics when it refined the "rear-view racer format" where the player’s view is behind and above the vehicle, looking forward along the road with the horizon in sight. The style would remain in wide use even after true 3D graphics became standard for racing games.

- Rail shooter: Astron Belt (1983) was an early first-person rail shooter, in addition to being a Laserdisc video game. It featured live-action FMV footage over which the player/enemy ships and laser fire are superimposed.[52] Space Harrier (1985) was an early rail shooter that broke new ground graphically and its wide variety of settings across multiple levels gave players more to aim for than high scores.[66][67] It was also an early example of a third-person shooter.[68]

- Real-time strategy: Herzog Zwei (1989) is considered to be the first real-time strategy game, predating the genre-popularizing Dune II; unlike its 1988 predecessor (Herzog), it features outposts that can be used to gain additional revenue; making it a strategic game as well as a tactical one.[69][70][71] It is the earliest example of a game with a feature set that falls under the contemporary definition of modern RTS.[72][73]

- Run & gun shooters: Hover Attack (1984) for the Sharp X1 was an early run & gun shooter that freely scrolled in all directions and allowed the player to shoot diagonally as well as straight ahead. The following year saw the release of Thexder (1985), a breakthrough title for run & gun shooters.[74] Commando (1985) was the first influential example of a shooter featuring characters on foot rather than in vehicles.[75]

- Rhythm game: Dance Aerobics was released in 1987, and allowed players to create music by stepping on Nintendo's Power Pad peripheral. It has been called the first rhythm-action game in retrospect.[76]

- Stealth games: 005 (1981), an arcade game by Sega, was the earliest example of a stealth-based game.[77][78][79] Metal Gear (1987), developed by Hideo Kojima, was the first stealth game in an action-adventure framework, and became the first commercially successful stealth game, spawning the Metal Gear series.

- Survival horror: Haunted House (1981) introduced elements of horror fiction into video games. Sweet Home (1989) introduced many of the modern staples of the survival horror genre. Gameplay involved battling horrifying creatures and solving puzzles. Developed by Capcom, the game would become an influence upon their later release Resident Evil (1996), making use of its design concepts such as the mansion setting and "opening door" load screen.[80]

- Vehicle simulation games: Battlezone (1980) used wireframe vector graphics to create the first true three-dimensional game world. Elite (1984), designed by David Braben and Ian Bell, ushered in the age of modern style 3D graphics. The game contains convincing vector worlds, full 6 degree freedom of movement, and thousands of visitable planetary systems. It is considered a pioneer of the space flight simulator game genre.

- Visual novels: Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (1983), developed by Yuji Horii (of Dragon Quest fame), was the first visual novel and one of the earliest Japanese graphic adventure games. It is viewed in a first-person perspective, follows a first-person narrative, and was the first Japanese adventure game to feature colour graphics. It inspired Hideo Kojima (of Metal Gear fame) to enter the video game industry and later produce his own classic graphic adventure, Snatcher (1988).

Gaming computers

Following the success of the Apple II and Commodore PET in the late 1970s a series of cheaper and incompatible rivals emerged in the early 1980s. This second batch included the Commodore Vic 20 and 64; Sinclair ZX80, ZX81 and ZX Spectrum; NEC PC-8000, PC-6001, PC-88 and PC-98; Sharp X1 and X68000; and Atari 8-bit family, BBC Micro, Acorn Electron, Amstrad CPC, and MSX series. These rivals helped to catalyze both the Home Computer and Games markets, by raising awareness of computing and gaming through their competing advertising campaigns.

The Sinclair, Acorn and Amstrad offerings were generally only known in Europe and Africa, the NEC and Sharp offerings were generally only known in Asia, and the MSX had a base in North and South America, Europe, and Asia, whilst the US based Apple, Commodore and Atari offerings were sold in both the USA and Europe.

In 1984, the computer gaming market took over from the console market following the crash of that year; computers offered equal gaming ability and since their simple design allowed games to take complete command of the hardware after power-on, they were nearly as simple to start playing with as consoles.

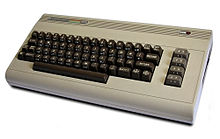

The Commodore 64 was released to the public in August 1982. It found initial success because it was marketed and priced aggressively. It had a BASIC programming environment and advanced graphic and sound capabilities for its time, similar to the ColecoVision console. It also utilized the same game controller ports popularized by the Atari 2600, allowing gamers to use their old joysticks with the system. It would become the most popular home computer of its day in the USA and many other countries and the best-selling single computer model of all time internationally.

At around the same time, the Sinclair ZX Spectrum was released in the United Kingdom and quickly became the most popular home computer in many areas of Western Europe—and later the Eastern Bloc—due to the ease with which clones could be produced.

The IBM PC compatible computer became a technically competitive gaming platform with IBM’s PC/AT in 1984. The primitive 4-color CGA graphics of previous models had limited the PC’s appeal to the business segment, as its graphics failed to compete with the C64 or Apple II. The new 16-color EGA display standard allowed its graphics to approach the quality seen in popular home computers like the Commodore 64. The sound capabilities of the AT, however, were still limited to the PC speaker, which was substandard compared to the built-in sound chips used in many home computers. Also, the relatively high cost of the PC compatible systems severely limited their popularity in gaming.

The Apple Macintosh also arrived at this time. It lacked the color capabilities of the earlier Apple II, instead preferring a much higher pixel resolution, but the operating system support for the GUI attracted developers of some interesting games (e.g. Lode Runner) even before color returned in 1987 with the Mac II.

The arrival of the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga in 1985 was the beginning of a new era of 16-bit machines. For many users they were too expensive until later on in the decade, at which point advances in the IBM PC’s open platform had caused the IBM PC compatibles to become comparably powerful at a lower cost than their competitors. The VGA standard developed for IBM’s new PS/2 line in 1987 gave the PC the potential for 256-color graphics. This was a big jump ahead of most 8-bit home computers but still lagging behind platforms with built-in sound and graphics hardware like the Amiga. This caused an odd trend around '89-91 towards developing to a seemingly inferior machine. Thus while both the ST and Amiga were host to many technically excellent games, their time of prominence proved to be shorter than that of the 8-bit machines, which saw new ports well into the 80s and even the 90s.

The Yamaha YM3812 sound chip.

The Yamaha YM3812 sound chip.

Dedicated sound cards started to address the issue of poor sound capabilities in IBM PC compatibles in the late 1980s. Ad Lib set an early de facto standard for sound cards in 1987, with its card based on the Yamaha YM3812 sound chip. This would last until the introduction of Creative Labs' Sound Blaster in 1989, which took the chip and added new features while remaining compatible with Ad Lib cards, and creating a new de facto standard. However, many games would still support these and rarer things like the Roland MT-32 and Disney Sound Source into the early 90s. The initial high cost of sound cards meant they would not find widespread use until the 1990s.

Shareware gaming first appeared in the mid 1980s, but its big successes came in the 1990s.[citation needed]

Early online gaming

Dial-up bulletin board systems were popular in the 1980s, and sometimes used for online game playing. The earliest such systems were in the late 1970s and early 1980s and had a crude plain-text interface. Later systems made use of terminal-control codes (the so-called ANSI art, which included the use of IBM-PC-specific characters not part of an ANSI standard) to get a pseudo-graphical interface. Some BBSs offered access to various games which were playable through such an interface, ranging from text adventures to gambling games like blackjack (generally played for "points" rather than real money). On some multiuser BBSs (where more than one person could be online at once), there were games allowing users to interact with one another.

SuperSet Software created Snipes, a text-mode networked computer game in 1983 to test a new IBM Personal Computer based computer network and demonstrate its capabilities. Snipes is officially credited as being the original inspiration for Novell NetWare. It is believed to be the first network game ever written for a commercial personal computer and is recognized alongside 1974’s Maze War (a networked multiplayer maze game for several research machines) and Spasim (a 3D multiplayer space simulation for time shared mainframes) as the precursor to multiplayer games such as 1987's MIDI Maze, and Doom in 1993. Commercial online services also arose during this decade. The first user interfaces were plain-text—similar to BBSs— but they operated on large mainframe computers, permitting larger numbers of users to be online at once. By the end of the decade, inline services had fully graphical environments using software specific to each personal computer platform. Popular text-based services included CompuServe, The Source, and GEnie, while platform-specific graphical services included PlayNET and Quantum Link for the Commodore 64, AppleLink for the Apple II and Macintosh, and PC Link for the IBM PC—all of which were run by the company which eventually became America Online—and a competing service, Prodigy. Interactive games were a feature of these services, though until 1987 they used text-based displays, not graphics.

Handheld LCD games

In 1979, Milton Bradley Company released the first handheld system using interchangeable cartridges, Microvision. While the handheld received modest success in the first year of production, the lack of games, screen size and video game crash of 1983 brought about the system's quick demise.[81]

In 1980, Nintendo released its Game & Watch line, handheld electronic game which spurred dozens of other game and toy companies to make their own portable games, many of which were copies of Game & Watch titles or adaptations of popular arcade games. Improving LCD technology meant the new handhelds could be more reliable and consume fewer batteries than LED or VFD games, most only needing watch batteries. They could also be made much smaller than most LED handhelds, even small enough to wear on one’s wrist like a watch. Tiger Electronics borrowed this concept of videogaming with cheap, affordable handhelds and still produces games in this model to the present day.

Video game crash of 1983

Main article: North American video game crash of 1983At the end of 1983, the industry experienced losses more severe than the 1977 crash. This was the "crash" of the video game industry, as well as the bankruptcy of several companies that produced North American home computers and video game consoles from late 1983 to early 1984. It brought an end to what is considered to be the second generation of console video gaming. Causes of the crash include the production of poorly-designed games, the most notorious of which included E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Pac-Man for the Atari 2600 console. Popular lore surrounding this now-legendary crash states that sales of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial diverged so poorly from their forecasts, that Atari buried thousands of unsold cartridges in a landfill in New Mexico.

Third generation consoles (1983–1995) (8-bit)

Main article: History of video game consoles (third generation) The Nintendo Entertainment System or NES.

The Nintendo Entertainment System or NES.

In 1985, the North American video game console market was revived with Nintendo’s release of its 8-bit console, the Famicom, known outside Asia as Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It was bundled with Super Mario Bros. and instantly became a success. The NES dominated the North American and the Japanese market until the rise of the next generation of consoles in the early 1990s. Other markets were not as heavily dominated, allowing other consoles to find an audience like the Sega Master System in Europe, Australia and Brazil (though it was sold in North America as well).

In the new consoles, the gamepad or joypad, took over joysticks, paddles, and keypads as the default game controller included with the system. The gamepad design of an 8 direction Directional-pad (or D-pad for short) with 2 or more action buttons became the standard.

The Legend of Zelda series made its debut in 1986 with The Legend of Zelda. In the same year, the Dragon Quest series debuted with Dragon Quest, and has created a phenomenon in Japanese culture ever since. The next year, the Japanese company Square was struggling and Hironobu Sakaguchi decided to make his final game—a role-playing game (RPG) modeled after Dragon Quest and titled Final Fantasy—resulting in Final Fantasy series, which would later go on to become the most successful RPG franchise. 1987 also saw the birth of the stealth game genre with Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear series' first game Metal Gear on the MSX2 computer—and ported to the NES shortly after. In 1989, Capcom released Sweet Home on the NES, which served as a precursor to the survival horror genre.

In 1988, Nintendo published their first issue of Nintendo Power magazine.[82]

This generation ended with the discontinuation of the NES in 1995.

1990s

Main article: 1990s in video gamingThe 1990s were a decade of marked innovation in video gaming. It was a decade of transition from raster graphics to 3D graphics and gave rise to several genres of video games including first-person shooter, real-time strategy, and MMO. Handheld gaming began to become more popular throughout the decade, thanks in part to the release of the Game Boy in 1989.[83] Arcade games, although still relatively popular in the early 1990s, begin a decline as home consoles become more common.

The video game industry matured into a mainstream form of entertainment in the 1990s. Major developments of the 1990s included the beginning of a larger consolidation of publishers, higher budget games, increased size of production teams and collaborations with both the music and motion picture industries. Examples of this would be Mark Hamill's involvement with Wing Commander III or the introduction of QSound.

The increasing computing power and decreasing cost of processors as the Intel 80386, Intel 80486, and the Motorola 68030, caused the rise of 3D graphics, as well as "multimedia" capabilities through sound cards and CD-ROMs. Early 3D games began with flat-shaded graphics (Elite, Starglider 2 or Alpha Waves[84]), and then simple forms of texture mapping (Wolfenstein 3D).

1989 and the early 1990s saw the release and spread of the MUD codebases DikuMUD and LPMud, leading to a tremendous increase in the proliferation and popularity of MUDs. Before the end of the decade, the evolution of the genre continued through "graphical MUDs" into the first MMORPGs (Massively multiplayer online role-playing games), such as Ultima Online and EverQuest, which freed users from the limited number of simultaneous players in other games and brought persistent worlds to the mass market. A prime example of an MMORPG MUD is the game Runescape created by Jagex.

In the early 1990s, shareware distribution was a popular method of publishing games for smaller developers, including then-fledgling companies such as Apogee (now 3D Realms), Epic Megagames (now Epic Games), and id Software. It gave consumers the chance to try a trial portion of the game, usually restricted to the game’s complete first section or "episode", before purchasing the rest of the adventure. Racks of games on single 5 1/4" and later 3.5" floppy disks were common in many stores, often only costing a few dollars each. Since the shareware versions were essentially free, the cost only needed to cover the disk and minimal packaging. As the increasing size of games in the mid-90s made them impractical to fit on floppies, and retail publishers and developers began to earnestly mimic the practice, shareware games were replaced by shorter game demos (often only one or two levels), distributed free on CDs with gaming magazines and over the Internet.

In 1991, Sonic the Hedgehog was introduced. The game gave Sega's Mega Drive console mainstream popularity, and rivaled Nintendo's Mario franchise. Its namesake character became the mascot of Sega and one of the most recognizable video game characters.

In 1992 the game Dune II was released. It was by no means the first in the genre (several other games can be called the very first real-time strategy game, see the History of RTS), but it set the standard game mechanics for later blockbuster RTS games such as Warcraft: Orcs & Humans, Command & Conquer, and StarCraft. The RTS is characterized by an overhead view, a "mini-map", and the control of both the economic and military aspects of an army. The rivalry between the two styles of RTS play—Warcraft style, which used GUIs accessed once a building was selected, and C&C style, which allowed construction of any unit from within a permanently visible menu—continued into the start of the next millennium.

Alone in the Dark (1992), while not the first survival horror game, planted the seeds of what would become known as the survival horror genre today. It took the action-adventure style and retooled it to de-emphasize combat and focus on investigation. An early attempt to simulate 3D scenarios by mixing polygons with 2D background images, it established the formula that would later flourish on CD-ROM based consoles, with games such as Resident Evil which coined the name "survival horror" and popularized the genre, and Silent Hill.

Adventure games continued to evolve, with Sierra Entertainment’s King's Quest series, and LucasFilms'/LucasArts' Monkey Island series bringing graphical interaction and the creation of the concept of "point-and-click" gaming. Myst and its sequels inspired a new style of puzzle-based adventure games. Published in 1993, Myst itself was one of the first computer games to make full use of the new high-capacity CD-ROM storage format. Despite Myst’s mainstream success, the increased popularity of action-based and real-time games led adventure games and simulation video games, both mainstays of computer games in earlier decades, to begin to fade into obscurity.

It was in the 1990s that Maxis began publishing its successful line of "Sim" games, beginning with SimCity, and continuing with a variety of titles, such as SimEarth, SimCity 2000, SimAnt, SimTower, and the best-selling PC game in history, The Sims, in early 2000.

In 1996, 3dfx Interactive released the Voodoo chipset, leading to the first affordable 3D accelerator cards for personal computers. These devoted 3D rendering daughter cards performed a portion of the computations required for more-detailed three-dimensional graphics (mainly texture filtering), allowing for more-detailed graphics than would be possible if the CPU were required to handle both game logic and all the graphical tasks. First-person shooter games (notably Quake) were among the first to take advantage of this new technology. While other games would also make use of it, the FPS would become the chief driving force behind the development of new 3D hardware, as well as the yardstick by which its performance would be measured, usually quantified as the number of frames per second rendered for a particular scene in a particular game.

Several other, less-mainstream, genres were created in this decade. Looking Glass Studios' Thief: The Dark Project and its sequel were the first to coin the term "first person sneaker", although it is questionable whether they are the first "first person stealth" games. Turn-based strategy progressed further, with the Heroes of Might and Magic (HOMM) series (from The 3DO Company) luring many mainstream gamers into this complex genre.Id Software’s 1996 game Quake pioneered play over the Internet in first-person shooters. Internet multiplayer capability became a de facto requirement in almost all FPS games. Other genres also began to offer online play, including RTS games like Microsoft Game Studios’ Age of Empires, Blizzard’s Warcraft and StarCraft series, and turn-based games such as Heroes of Might and Magic. Developments in web browser plug-ins like Java and Adobe Flash allowed for simple browser-based games. These are small single player or multiplayer games that can be quickly downloaded and played from within a web browser without installation. Their most popular use is for puzzle games, side-scrollers, classic arcade games, and multiplayer card and board games.

Few new genres have been created since the advent of the FPS and RTS, with the possible exception of the third-person shooter. Games such as Grand Theft Auto III, Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell, Enter the Matrix, and Hitman all use a third-person camera perspective, but are otherwise very similar to their first-person counterparts.

1998 marked another great advance, which came in the form of Descent: FreeSpace - The Great War, by Volition Inc. It was one of the better 3D games which was a space flight simulation (Sci-Fi) and it was followed up by FreeSpace_2 in 1999, which had many more graphical updates and even more innovations included.

Decline of arcades

With the advent of 16-bit and 32-bit consoles, home video games began to approach the level of graphics seen in arcade games. An increasing number of players would wait for popular arcade games to be ported to consoles rather than going out. Arcades experienced a resurgence in the early to mid 1990s with games such as Street Fighter II, Mortal Kombat, and other games in the one-on-one fighting game genre, as well as racing games such as Virtua Racing and sports games such as NBA Jam. As patronage of arcades declined, many were forced to close down. Classic coin-operated games have largely become the province of dedicated hobbyists and as a tertiary attraction for some businesses, such as movie theaters, batting cages, miniature golf, and arcades attached to game stores such as F.Y.E..

The gap left by the old corner arcades was partly filled by large amusement centers dedicated to providing clean, safe environments and expensive game control systems not available to home users. These are usually based on sports like skiing or cycling, as well as rhythm games like Dance Dance Revolution, which have carved out a large slice of the market. Dave & Buster's and GameWorks are two large chains in the United States with this type of environment. Aimed at adults and older kids, they feature full service restaurants with full liquor bars and have a wide variety of video game and hands on electronic gaming options. Chuck E. Cheese's is a similar type of establishment focused towards small children.

Handhelds come of age

In 1989, Nintendo released the Game Boy, the first handheld console since the ill-fated Microvision ten years before. The design team headed by Gunpei Yokoi had also been responsible for the Game & Watch systems. Included with the system was Tetris, a popular puzzle game. Several rival handhelds also made their debut around that time, including the Sega Game Gear and Atari Lynx (the first handheld with color LCD display). Although most other systems were more technologically advanced, they were hampered by higher battery consumption and less third-party developer support. While some of the other systems remained in production until the mid-90s, the Game Boy remained at the top spot in sales throughout its lifespan.[citation needed]

Fourth generation consoles (1989–1999) (16-bit)

Main article: History of video game consoles (fourth generation)The Mega Drive/Genesis proved its worth early on after its debut in 1989. Nintendo responded with its own next generation system known as the Super NES in 1991. The TurboGrafx-16 debuted early on alongside the Genesis, but did not achieve a large following in the U.S. due to a limited library of games and excessive distribution restrictions imposed by Hudson.

Mortal Kombat, released in both SNES and Genesis consoles, was one of the most popular game franchises of its time.

Mortal Kombat, released in both SNES and Genesis consoles, was one of the most popular game franchises of its time.

The intense competition of this time was also a period of not entirely truthful marketing. The TurboGrafx-16 was billed as the first 16-bit system but its central processor was an 8-bit HuC6280, with only its HuC6270 graphics processor being a true 16-bit chip. Additionally, the much earlier Mattel Intellivision contained a 16-bit processor. Sega, too, was known to stretch the truth in its marketing approach; they used the term "Blast Processing" to describe the simple fact that their console's CPU ran at a higher clock speed than that of the SNES (7.67 MHz vs 3.58 MHz).

In Japan, the 1987 success of the PC Engine (as the TurboGrafx-16 was known there) against the Famicom and CD drive peripheral allowed it to fend off the Mega Drive (Genesis) in 1988, which never really caught on to the same degree as outside Japan. The PC Engine eventually lost out to the Super Famicom, but, due to its popular CD add-ons, retained enough of a user base to support new games well into the late 1990s.

CD-ROM drives were first seen in this generation, as add-ons for the PC Engine in 1988 and the Mega Drive in 1991. Basic 3D graphics entered the mainstream with flat-shaded polygons enabled by additional processors in game cartridges like Virtua Racing and Star Fox.

SNK's Neo-Geo was the most expensive console by a wide margin when it was released in 1990, and would remain so for years. It was also capable of 2D graphics in a quality level years ahead of other consoles. The reason for this was that it contained the same hardware that was found in SNK's arcade games. This was the first time since the home Pong machines that a true-to-the-arcade experience could be had at home.

This generation ended with the SNES's discontinuation in 1999.

Fifth generation consoles (1993–2006) (32 and 64-bit)

Main article: History of video game consoles (fifth generation) Metal Gear Solid, notable for its innovative use of in-game generated cinemas, detailed integration of haptic technology, and theatrical story delivery.

Metal Gear Solid, notable for its innovative use of in-game generated cinemas, detailed integration of haptic technology, and theatrical story delivery.

In 1993, Atari re-entered the home console market with the introduction of the Atari Jaguar. Also in 1993, The 3DO Company released the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, which, though highly advertised and promoted, failed to catch up to the sales of the Jaguar, due its high pricetag. Both consoles had very low sales and few quality games, eventually leading to their demise. In 1994, three new consoles were released in Japan: the Sega Saturn, the PlayStation, and the PC-FX, the Saturn and the PlayStation later seeing release in North America in 1995. The PlayStation quickly outsold all of its competitors, with the exception of the aging Super Nintendo Entertainment System, which still had the support of many major game companies.

The Virtual Boy from Nintendo was released in 1995 but did not achieve high sales. In 1996 the Virtual Boy was taken off the market.

After many delays, Nintendo released its 64-bit console, the Nintendo 64 in 1996. The console's flagship title, Super Mario 64, became a defining title for 3D platformer games.

PaRappa the Rapper popularized rhythm, or music video games in Japan with its 1996 debut on the PlayStation. Subsequent music and dance games like beatmania and Dance Dance Revolution became ubiquitous attractions in Japanese arcades. While Parappa, DDR, and other games found a cult following when brought to North America, music games would not gain a wide audience in the market until the next decade. Also in 1996 Capcom released Resident Evil, the first well known survival horror game. It was a huge success selling over 2 million copies and is considered one of the best games on the Playstation.

Other milestone games of the era include Rare's Nintendo 64 title GoldenEye 007 (1997), which was critically acclaimed for bringing innovation as being the first major first-person shooter that was exclusive to a console, and for pioneering certain features that became staples of the genre, such as scopes, headshots, and objective-based missions.[citation needed] The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) for the Nintendo 64 is widely considered the highest critically acclaimed game of all time.[85] The title also featured many innovations such as Z-targeting which is commonly used in many games today.

Nintendo's choice to use cartridges instead of CD-ROMs for the Nintendo 64, unique among the consoles of this period, proved to have negative consequences. While cartridges were faster and combated piracy, CDs could hold far more data and were much cheaper to produce, causing many game companies to turn to Nintendo's CD-based competitors. In particular, Square, which had released all previous games in its Final Fantasy series for Nintendo consoles, now turned to the PlayStation; Final Fantasy VII (1997) was a huge success, establishing the popularity of role-playing games in the west and making the PlayStation the primary console for the genre.

By the end of this period, Sony had become the leader in the video game market. The Saturn was moderately successful in Japan but a commercial failure in North America and Europe, leaving Sega outside of the main competition. The N64 achieved huge success in North America and Europe, though it never surpassed PlayStation's sales or was as popular in Japan.

This generation ended with the PlayStation discontinuation in March 2006.

Transition to 3D and CDs

The fifth generation is most noted for the rise of fully 3D games. While there were games prior that had used three dimensional environments, such as Virtua Racing and Star Fox, it was in this era that many game designers began to move traditionally 2D and pseudo-3D genres into full 3D. Super Mario 64 on the N64, Crash Bandicoot on the PlayStation and Nights into Dreams on the Saturn, are prime examples of this trend. Their 3D environments were widely marketed and they steered the industry's focus away from side-scrolling and rail-style titles, as well as opening doors to more complex games and genres. Games like GoldenEye 007, The Legend Of Zelda: Ocarina of Time or Virtua Fighter were nothing like shoot-em-ups, RPG's or fighting games before them. 3D became the main focus in this era as well as a slow decline of cartridges in favor of CDs.

Mobile phone gaming

Main article: Mobile gameMobile phones began becoming videogaming platforms when Nokia installed Snake onto its line of mobile phones in 1998. Soon every major phone brand offered "time killer games" that could be played in very short moments such as waiting for a bus. Mobile phone games early on were limited by the modest size of the phone screens that were all monochrome and the very limited amount of memory and processing power on phones, as well as the drain on the battery.

2000s

Main article: 2000s in video gamingThe first decade of the 2000s showed innovation on both consoles and PCs, and an increasingly competitive market for portable game systems.

The phenomena of user-created modifications (or "mods") for games, one trend that began during the Wolfenstein 3D and Doom-era, continued into the turn of the millennium. The most famous example is that of Counter-Strike; released in 1999, it is still the most popular online first-person shooter, even though it was created as a mod for Half-Life by two independent programmers. Eventually, game designers realized the potential of mods and custom content in general to enhance the value of their games, and so began to encourage its creation. Some examples of this include Unreal Tournament, which allowed players to import 3dsmax scenes to use as character models, and Maxis' The Sims, for which players could create custom objects.

Sixth generation consoles (1998–2011)

Main article: History of video game consoles (sixth generation)In the sixth generation of video game consoles, Sega exited the hardware market, Nintendo fell behind, Sony solidified its lead in the industry, and Microsoft developed a gaming console.

The generation opened with the launch of the Dreamcast in 1998. It was the first console to have a built-in modem for Internet support and online play. While it was initially successful, sales and popularity would soon begin to decline with contributing factors being Sega's damaged reputation from previous commercial failures, software pirating, and the overwhelming anticipation for the upcoming Playstation 2. Production for the console would discontinue in most markets by 2002 and would be Sega's final console before becoming a third party game provider only.

The second release of the generation was Sony's Playstation 2. Nintendo followed a year later with the Nintendo GameCube, their first disc-based console. The Nintendo GameCube suffered from a lack of third-party games compared to Sony's system, and was hindered by a reputation for being a "kid's console" and lacking the mature games the current market appeared to want.

The Xbox, Microsoft's entry into the video game console industry.

The Xbox, Microsoft's entry into the video game console industry.

Before the end of 2001, Microsoft Corporation, best known for its Windows operating system and its professional productivity software, entered the console market with the Xbox. Based on Intel's Pentium III CPU, the console used much PC technology to leverage its internal development. In order to maintain its hold in the market, Microsoft reportedly sold the Xbox at a significant loss[86] and concentrated on drawing profit from game development and publishing. Shortly after its release in November 2001 Bungie Studio's Halo: Combat Evolved instantly became the driving point of the Xbox's success, and the Halo series would later go on to become one of the most successful console shooters of all time. By the end of the generation, the Xbox had drawn even with the Nintendo GameCube in sales globally, but since nearly all of its sales were in North America, it pushed Nintendo into third place in the American market.

In 2001 Grand Theft Auto III was released, popularizing open world games by using a non-linear style of gameplay. It was very successful both critically and commercially and is considered a huge milestone in gaming.

Nintendo still dominated the handheld gaming market in this generation. The Game Boy Advance in 2001, maintained Nintendo's market position. Finnish cellphone maker Nokia entered the handheld scene with the N-Gage, but it failed to win a significant following.

Console gaming largely continued the trend established by the PlayStation toward increasingly complex, sophisticated, and adult-oriented gameplay. Most of the successful sixth-generation console games were games rated T and M by the ESRB, including many now-classic gaming franchises such as Halo and Resident Evil, the latter of which was notable for both its success and its notoriety. Even Nintendo, widely known for its aversion to adult content (with very few exceptions most notably Conker's Bad Fur Day for the Nintendo 64), began publishing more M-rated games, with Silicon Knights's Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem and Capcom's Resident Evil 4 being prime examples. This trend in hardcore console gaming would partially be reversed with the seventh generation release of the Wii. As of 2011, the PlayStation 2 is still in production and continues to sell steadily over a decade after its original release.[87]

Return of alternate controllers

One significant feature of this generation was various manufacturers' renewed fondness for add-on peripheral controllers. While alternate controllers weren't new, as Nintendo featured several with the original NES and PC gaming has previously featured driving wheels and aircraft joysticks, for the first time console games using them became some of the biggest hits of the decade. Konami introduced a soft plastic mat versions of its foot controls for its Dance Dance Revolution franchise in 1998. Sega's alternate peripherals included Samba De Amigo's maraca controllers. Nintendo introduced a bongo controller for a few titles in its Donkey Kong franchise. Publisher RedOctane introduced Guitar Hero and its distinctive guitar-shaped controllers for the PlayStation 2. Meanwhile, Sony introduced the EyeToy peripheral, a camera that could detect player movement, for the PlayStation 2.

Online gaming rises to prominence

As affordable broadband Internet connectivity spread, many publishers turned to online gaming as a way of innovating. Massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPGs) featured significant titles for the PC market like EverQuest, World of Warcraft, and Ultima Online. Historically, console based MMORPGs have been few in number due to the lack of bundled Internet connectivity options for the platforms. This made it hard to establish a large enough subscription community to justify the development costs. The first significant console MMORPGs were Phantasy Star Online on the Sega Dreamcast (which had a built in modem and after market Ethernet adapter), followed by Final Fantasy XI for the Sony PlayStation 2 (an aftermarket Ethernet adapter was shipped to support this game). Every major platform released since the Dreamcast has either been bundled with the ability to support an Internet connection or has had the option available as an aftermarket add-on. Microsoft's Xbox also had its own online gaming service called Xbox Live. Xbox Live was a huge success and proved to be a driving force for the Xbox with games like Halo 2 that were overwhelmingly popular.

Mobile games

Main article: Mobile gameIn the early 2000s, mobile games had gained mainstream popularity in Japan's mobile phone culture, years before the United States or Europe. By 2003, a wide variety of mobile games were available on Japanese phones, ranging from puzzle games and virtual pet titles that utilize camera phone and fingerprint scanner technologies to 3D games with PlayStation-quality graphics. Older arcade-style games became particularly popular on mobile phones, which were an ideal platform for arcade-style games designed for shorter play sessions. Namco began making attempts to introduce mobile gaming culture to Europe in 2003.[88]

Mobile gaming interest was raised when Nokia launched its N-Gage phone and handheld gaming platform in 2003. While about two million handsets were sold, the product line wasn't seen as a success and withdrawn from Nokia's lineup. Meanwhile, many game developers had noticed that more advanced phones had color screens and reasonable memory and processing power to do reasonable gaming. Mobile phone gaming revenues passed 1 billion dollars in 2003, and passed 5 billion dollars in 2007, accounting for a quarter of all videogaming software revenues. More advanced phones came to the market such as the N-Series smartphone by Nokia in 2005 and the iPhone by Apple in 2007 which strongly added to the appeal of mobile phone gaming. In 2008 Nokia didn't revise the N-Gage brand, but only published a software library of games to its top-end phones. At Apple's App Store in 2008, more than half of all applications sold were iPhone games.

Seventh generation consoles (2004–present)

Main article: History of video game consoles (seventh generation)The generation opened early for handheld consoles, as Nintendo introduced their Nintendo DS and Sony premiered the PlayStation Portable (PSP) within a month of each other in 2004. While the PSP boasted superior graphics and power, following a trend established since the mid 1980s, Nintendo gambled on a lower-power design but featuring a novel control interface. The DS's two screens, one of which was touch-sensitive, proved extremely popular with consumers, especially young children and middle-aged gamers, who were drawn to the device by Nintendo's Nintendogs and Brain Age series, respectively. While the PSP attracted a significant portion of veteran gamers, the DS allowed Nintendo to continue its dominance in handheld gaming. Nintendo updated their line with the Nintendo DS Lite in 2006, the Nintendo DSi in 2008 (Japan) and 2009 (Americas and Europe), and the Nintendo DSi XL while Sony updated the PSP in 2007 and again with the smaller PSP Go in 2009. Nokia withdrew their N-Gage platform in 2005 but reintroduced the brand as a game-oriented service for high-end smartphones on April 3, 2008.[89]

In console gaming, Microsoft stepped forward first in November 2005 with the Xbox 360, and Sony followed in 2006 with the PlayStation 3, released in Europe in March 2007. Setting the technology standard for the generation, both featured high-definition graphics, large hard disk-based secondary storage, integrated networking, and a companion on-line gameplay and sales platform, with Xbox Live and the PlayStation Network, respectively. Both were formidable systems that were the first to challenge personal computers in power (at launch) while offering a relatively modest price compared to them. While both were more expensive than most past consoles, the Xbox 360 enjoyed a substantial price edge, selling for either $300 or $400 depending on model, while the PS3 launched with models priced at $500 and $600. Coming with Blu-ray and Wi-Fi, the PlayStation 3 was the most expensive game console on the market since Panasonic's version of the 3DO, which retailed for little under 700USD.[90]

Nintendo would release their Wii console shortly after the PlayStation 3's launch, and the platform would put Nintendo back on track in the console race. While the Wii had lower technical specifications (and a lower price) than both the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3,[91] its new motion control was much touted. Many gamers, publishers, and analysts initially dismissed the Wii as an underpowered curiosity, but were surprised as the console sold out through the 2006 Christmas season, and remained so through the next 18 months, becoming the fastest selling game console in most of the world's gaming markets.[92]

In June 2009, Sony announced that it would release its PSP Go for 249.99USD on October 1 in Europe and North America, and Japan on November 1. The PSP Go was a newer, slimmer version of the PSP, which had the control pad slide from the base, where its screen covers most of the front side.[93]

Increases in development budgets

With high definition video an undeniable hit with veteran gamers seeking immersive experiences, expectations for visuals in games along with the increasing complexity of productions resulted in a spike in the development budgets of gaming companies. While many game studios saw their Xbox 360 projects pay off, the unexpected weakness of PS3 sales resulted in heavy losses for some developers, and many publishers broke previously arranged PS3 exclusivity arrangements or cancelled PS3 game projects entirely in order to cut losses.[citation needed]

Nintendo capitalizes on casual gaming

Meanwhile, Nintendo took cues from PC gaming and their own success with the Nintendo Wii, and crafted games that capitalized on the intuitive nature of motion control. Emphasis on gameplay turned comparatively simple games into unlikely runaway hits, including the bundled game, Wii Sports, and Wii Fit. As the Wii sales spiked, many publishers were caught unprepared and responded by assembling hastily created titles to fill the void. Although some hardcore games continued to be produced by Nintendo, many of their classic franchises were reworked into "bridge games", meant to provide new gamers crossover experiences from casual gaming to deeper experiences, including their flagship Wii title, Super Mario Galaxy, which in spite of its standard-resolution graphics dominated critics' "best-of" lists for 2007. Many others, however, strongly criticized Nintendo for its apparent spurning of its core gamer base in favor of a demographic many warned would be fickle and difficult to keep engaged.

Motion control revolutionizes game play