- PDP-10

-

The PDP-10 was a mainframe computer family[1] manufactured by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) from the late 1960s on; the name stands for "Programmed Data Processor model 10". The first model was delivered in 1966.[2] It was the machine that made time-sharing common; it looms large in hacker folklore because of its adoption in the 1970s by many university computing facilities and research labs, the most notable of which were MIT's AI Lab and Project MAC, Stanford's SAIL, Computer Center Corporation (CCC), and Carnegie Mellon University.

The PDP-10 architecture was an almost identical version of the earlier PDP-6 architecture, sharing the same 36-bit word length and slightly extending the instruction set (but with improved hardware implementation). Some aspects of the instruction set are unique, most notably the "byte" instructions, which operated on bit fields of any size from 1 to 36 bits inclusive according to the general definition of a byte as a contiguous sequence of a fixed number of bits.

Contents

Models and technical evolution

The original PDP-10 processor was the KA10, introduced in 1968. It used discrete transistors packaged in DEC's Flip-Chip technology, with backplanes wire wrapped via a semi-automated manufacturing process. In 1973, the KA10 was replaced by the KI10, which used TTL SSI. This was joined in 1975 by the higher-performance KL10 (later faster variants), which was built from ECL, was microprogrammed, and had cache memory. A smaller, less expensive model, the KS10, was introduced in 1978, using TTL and Am2901 bit-slice components and including the PDP-11 Unibus to connect peripherals.

KA10

The KA10 had a maximum main memory capacity (both virtual and physical) of 256 kilowords (equivalent to 1152 kilobytes). As supplied by DEC, it did not include paging hardware; memory management consisted of two sets of protection and relocation registers, called "base and bounds" registers. This allowed each half of a user's address space to be limited to a set section of main memory, designated by the base physical address and size. This allowed the model (later used by Unix) of separate read-only shareable code segment (normally the high segment) and read-write data/stack segment (normally the low segment). Some KA10 machines, first at MIT, and later at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), were modified to add virtual memory and support for demand paging, as well as more physical memory.

KI10 and KL10

The KI10 and later processors offered paged memory management, and also supported a larger physical address space of 4 megawords. KI10 models included 1060, 1070 and 1077, the latter incorporating two CPUs.

The original KL10 TOPS-10 (also marketed as DECsystem-10) models (1080, 1088, etc.) used the original PDP-10 memory bus, with external memory modules. Module in this context meant a cabinet, dimensions roughly (WxHxD) 30 x 75 x 30 in. with a capacity of 32 to 256 kWords of magnetic core memory (the picture on the right hand side of the introduction shows six of these cabinets). The processors used in the DECSYSTEM-20 (2040, 2050, 2060, 2065), commonly but incorrectly called "KL20", used internal memory, mounted in the same cabinet as the CPU. The 10xx models also had different packaging; they came in the original tall PDP-10 cabinets, rather than the short ones used later on for the DECSYSTEM-20. The differences between the 10xx and 20xx models were more cosmetic than real; some 10xx systems had "20-style" internal memory and I/O, and some 20xx systems had "10-style" external memory and an I/O bus. In particular, all ARPAnet TOPS-20 systems had an I/O bus because the AN20 IMP interface was an I/O bus device. Both could run either TOPS-10 or TOPS-20 microcode and thus the corresponding operating system.

MASSbus

The I/O architecture of the 20xx series KL machines was based on a new DEC bus design called the MASSbus. While many attributed the success of the PDP-11 to DEC's decision to make the PDP-11 Unibus an open architecture, DEC reverted to prior philosophy with the KL, making MASSbus both unique and proprietary. Consequently, there were no aftermarket peripheral manufacturers who made devices for the MASSbus, and DEC chose to price their own MASSbus devices, notably the RP06 disk drive, at a substantial premium above comparable IBM-compatible devices. CompuServe for one, designed its own alternative disk controller that could operate on the MASSbus, but connect to IBM style 3330 disk subsystems.

Model B

Later, the "Model B" version of the 2060 processors removed the 256 kiloword limitation on the virtual address space, by allowing the use of up to 32 "sections" of up to 256 kilowords each, along with substantial changes to the instruction set. "Model A" and "Model B" KL10 processors can be thought of as being different CPUs. The first operating system that took advantage of the Model B's capabilities was TOPS-20 release 3, and user mode extended addressing was offered in TOPS-20 release 4. TOPS-20 versions after release 4.1 would only run on a Model B.

KS10

The KS10 design was crippled to be a Model A even though most of the necessary data paths needed to support the Model B architecture were present. This was no doubt intended to segment the market, but it greatly shortened the KS10's product life.

MCA25

The final upgrade to the KL10 was the MCA25 upgrade of a 2060 to 2065, which gave some performance increases for programs which run in multiple sections.

Front End Systems

The KL class machines could not be started without the assist of a PDP-11/40 frontend computer installed in every system. The PDP-11 was booted from a dual-ported RP06 disk drive (or alternatively from an 8" floppy disk drive or DECtape), and then commands could be given to the PDP-11 to start the main processor, which was typically booted from the same RP06 disk drive as the PDP-11. The PDP-11 would perform watchdog functions once the main processor was running.

The KS system used a similar boot procedure. An 8080 CPU loaded the microcode from an RM03, RM80, or RP06 disk or magnetic tape and then started the main processor. The 8080 switched modes after the operating system booted and controlled the console and remote diagnostic serial ports.

Instruction set architecture

From the first PDP-6's to the Model A KL-10s, the user-mode instruction set architecture was largely the same. This section covers that architecture.

Addressing

The PDP-10 has 36-bit words and 18-bit word addresses. In supervisor mode, instruction addresses correspond directly to physical memory. In user mode, addresses are translated to physical memory. Earlier models gave a user process a "high" and a "low" memory: addresses with a 0 top bit used one base register, and higher addresses used another. Each segment was contiguous. Later architectures had paged memory access, allowing non-contiguous address spaces. The CPU's general-purpose registers can also be addressed as memory locations 0-15.

Registers

There are 16 general-purpose, 36-bit registers. The right half of these registers (other than register 0) may be used for indexing. A few instructions operate on pairs of registers. There is also a condition register, which records extra bits from the results of arithmetic operations (e.g. overflow), and can be accessed by only a few instructions.

Supervisor mode

There are two operational modes, supervisor and user mode. Besides the difference in memory referencing described above, supervisor-mode programs can execute input/output operations.

Communication from user-mode to supervisor-mode is done through Unimplemented User Operations (UUOs): instructions which are not defined by the hardware are trapped by the supervisor. This mechanism is also used to emulate operations which may not have hardware implementations in cheaper models.

Data types

The major datatypes which are directly supported by the architecture are two's complement 36-bit integer arithmetic (including bitwise operations), 36-bit floating-point, and halfwords. Extended, 72-bit, floating point is supported through special instructions designed to be used in multi-instruction sequences. Byte pointers are supported by special instructions. A word structured as a "count" half and a "pointer" half facilitates the use of bounded regions of memory, notably stacks.

Instructions

The instruction set is very symmetric. Every instruction consists of a 9-bit opcode, a 4-bit register code, and a 23-bit effective address field, which consists in turn of a 1-bit indirect bit, a 4-bit register code, and an 18-bit offset. Instruction execution begins by calculating the effective address. It adds the contents of the given register (if non-zero) to the offset; then, if the indirect bit is 1, fetches the word at the calculated address and repeats the effective address calculation until an effective address with a zero indirect bit is reached. The resulting effective address can be used by the instruction either to fetch memory contents, or simply as a constant. Thus, for example, MOVEI A,3(C) adds 3 to the 18 lower bits of register C and puts the result in register A, without touching memory.

There are three main classes of instruction: arithmetic, logical, and move; conditional jump; conditional skip (which may have side effects). There are also several smaller classes.

The arithmetic, logical, and move operations include variants which operate immediate-to-register, memory-to-register, register-to-memory, register-and-memory-to-both or memory-to-memory. Since registers may be addressed as part of memory, register-to-register operations are also defined. (Not all variants are useful, though they are well-defined.) For example, the ADD operation has as variants ADDI (add an 18-bit Immediate constant to a register), ADDM (add register contents to a Memory location), ADDB (add to Both, that is, add register contents to memory and also put the result in the register). A more elaborate example is HLROM (Half Left to Right, Ones to Memory), which takes the Left half of the register contents, places them in the Right half of the memory location, and replaces the left half of the memory location with Ones.

The conditional jump operations examine register contents and jump to a given location depending on the result of the comparison. The mnemonics for these instructions all start with JUMP, JUMPA meaning "jump always" and JUMP meaning "jump never" - as a consequence of the symmetrical design of the instruction set, it contains several no-ops such as JUMP. For example, JUMPN A,LOC jumps to the address LOC if the contents of register A is non-zero. There are also conditional jumps based on the processor's condition register using the JRST instruction. On the KA10 and KI10, JRST was faster than JUMPA, so the standard unconditional jump was JRST.

The conditional skip operations compare register and memory contents and skip the next instruction (which is often an unconditional jump) depending on the result of the comparison. A simple example is CAMN A,LOC which compares the contents of register A with the contents of location LOC and skips the next instruction if they are not equal. A more elaborate example is TLCE A,LOC (read "Test Left Complement, skip if Equal"), which using the contents of LOC as a mask, selects the corresponding bits in the left half of register A. If all those bits are Equal to zero, skip the next instruction; and in any case, replace those bits by their boolean complement.

Some smaller instruction classes include the shift/rotate instructions and the procedure call instructions. Particularly notable are the stack instructions PUSH and POP, and the corresponding stack call instructions PUSHJ and POPJ. The byte instructions use a special format of indirect word to extract and store arbitrary-sized bit fields, possibly advancing a pointer to the next unit.

Software

The original PDP-10 operating system was simply called "Monitor", but was later renamed TOPS-10. Eventually the PDP-10 system itself was renamed the DECsystem-10. Early versions of Monitor and TOPS-10 formed the basis of Stanford's WAITS operating system and the Compuserve time-sharing system.

Over time, some PDP-10 operators began running operating systems assembled from major components developed outside DEC. For example, the main Scheduler might come from one university, the Disk Service from another, and so on. The commercial timesharing services such as CompuServe, On-Line Systems (OLS), and Rapidata maintained sophisticated inhouse systems programming groups so that they could modify the operating system as needed for their own businesses without being dependent on DEC or others. There were also strong user communities such as DECUS through which users could share software that they had developed. In some ways, this was one of the first open source environments, although the commercial operators tended to only take code from open sources, keeping their own proprietary enhancements to themselves.

BBN developed their own alternative operating system, TENEX, which fairly quickly became the de facto standard in the research community. DEC later ported Tenex to the KL10, enhanced it considerably, and named it TOPS-20, forming the DECSYSTEM-20 line. MIT also had developed their own influential system, the Incompatible Timesharing System (named in parody of the Compatible Time-Sharing System, developed at MIT for a modified IBM 7094).

Tymshare developed TYMCOM-X, derived from TOPS-10 but using a page-based file system like TOPS-20.

Clones

In 1971 to 1972 researchers at Xerox PARC were frustrated by top company management's refusal to let them purchase a PDP-10. Xerox had just bought Scientific Data Systems in 1969, and wanted PARC to use an SDS machine. Instead, a group led by Charles P. Thacker designed and constructed two PDP-10 clone systems named "MAXC" (pronounced "Max", in honour of Max Palevsky, who had sold SDS to Xerox) for their own use. MAXC was also a backronym for Multiple Access Xerox Computer. MAXC ran a modified version of TENEX.[3]

Third-party attempts to sell PDP-10 clones were relatively unsuccessful; see Foonly, Systems Concepts, and XKL.

Usage by CompuServe

One of the largest collections of DECsystem-10 architecture systems ever assembled was at CompuServe, which at its peak operated over 200 loosely-coupled systems in three data centers in Columbus, Ohio. CompuServe used these systems as 'hosts', providing access to commercial applications as well as the CompuServe Information Service. While the first such systems were purchased from DEC, when DEC abandoned the PDP-10 architecture in favor of the VAX, CompuServe and other PDP-10 customers began purchasing plug-compatible computers from Systems Concepts. As of January 2007, CompuServe continues to operate a small number of PDP-10 architecture machines to perform some billing and routing functions.

The main power supplies used in the KL-series machines were so inefficient that CompuServe engineers designed a replacement power supply that consumed about half the energy. CompuServe offered to license the design for its KL power supply to DEC for free if DEC would promise that any new KL purchased by CompuServe would have the more efficient power supply installed. DEC declined the offer.

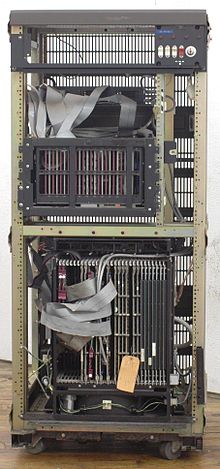

Another modification made to the PDP-10 by CompuServe engineers was the replacement of the hundreds of incandescent indicator lamps on the KI10 processor cabinet with LED lamp modules. The cost of the conversion was easily offset by the cost savings in electric consumption, the reduction of heat, and the manpower required to replaced burned-out lamps. Digital followed this step all over the world. The picture on the right hand side shows the light panel of the MF10 memory which is contemporaneous with the KI10 CPU. This item is part of a computer museum, and was populated with LEDs in 2008 for demonstration purposes only. There were no similar banks of indicator lamps on KL and KS processors.

Cancellation and influence

The PDP-10 was eventually eclipsed by the VAX superminicomputer machines (descendants of the PDP-11) when DEC recognized that the PDP-10 and VAX product lines were competing with each other and decided to concentrate its software development effort on the more profitable VAX. The PDP-10 product line cancellation was announced in 1983, including cancelling the on-going Jupiter project to produce a new high-end PDP-10 processor (despite that project being in good shape at the time of the cancellation) and the Minnow project to produce a desktop PDP-10, which may then have been at the prototyping stage.[4]

This event spelled the doom of ITS and the technical cultures that had spawned the original jargon file, but by the 1990s it had become something of a badge of honor among old-time hackers to have cut one's teeth on a PDP-10.

The PDP-10 assembly language instructions LDB and DPB (load/deposit byte) live on as functions in the programming language Common Lisp. See the "References" section on the LISP article — the 36-bit word size of the PDP-6 and PDP-10 was influenced by the programming convenience of having 2 LISP pointers, each 18 bits, in one word.

Will Crowther created Adventure, the prototypical computer adventure game, for a PDP-10. Don Daglow created the first computer baseball game (1971) and Dungeon (1975), the first role-playing video game on a PDP-10. Walter Bright originally created Empire for the PDP-10. Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle created the first MUD on a PDP-10. In addition, Zork was written on the PDP-10, and Infocom used several PDP-10s for game development and testing.

Emulation or simulation

The software for simulation of historical computers SIMH contains a module to emulate the KS10 CPU on a Windows or Unix-based machine. Copies of DEC's original distribution tapes are available as downloads from the Internet so that a running TOPS-10 or TOPS-20 system may be established. ITS is also available for SIMH.

Ken Harrenstien's KLH10 software for Unix-like systems emulates a KL10B processor with extended addressing and 4 MW of memory or a KS10 processor with 512 KW of memory. The KL10 emulation supports v.442 of the KL10 microcode, which enables it to run the final versions of both TOPS-10 and TOPS-20. The KS10 emulation supports both ITS v.262 microcode for the final version of KS10 ITS and DEC v.130 microcode for the final versions of KS TOPS-10 and TOPS-20.[5]

This article is based in part on the Jargon File, which is in the public domain.

See also

Further reading

- C. Gordon Bell, Alan Kotok, Thomas N. Hastings, Richard Hill, The Evolution of the DECsystem-10, in C. Gordon Bell, J. Craig Mudge, John E. McNamara, Computer Engineering: A DEC View of Hardware Systems Design (Digital, Bedford, 1979)

References

- ^ Ceruzzi, p. 208, "It was large—even DEC's own literature called it [PDP-10] a mainframe."

- ^ Ceruzzi, p. 139

- ^ Interviewed by Al Kossow (August 29, 2007). "Oral History of Charles (Chuck) Thacker". Reference no: X4148.2008. Computer History Museum. http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/Oral_History/102658126.05.01.acc.pdf. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ "DEC 36-bit Computers" Retrieved on April 4, 2009.

- ^ Tim Shoppa "Announcing KLH10", November 10, 2001. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- DECsystem10 System Reference Manual (DEC, 1968, 1971, 1974)

- DECsystem-10/DECSYSTEM-20 Processor Reference Manual (DEC, 1982)

- Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2003). A History of Modern Computing (2 ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 0262532034. http://books.google.com/books?id=x1YESXanrgQC.

External links

- 36 Bits Forever!

- PDP-10 stuff

- PDP10 Miscellany Page

- Life in the Fast AC's

- Columbia University DEC PDP-10 page

- Panda Programming TOPS-20 page

- Living Computer Museum, a portal into the Paul Allen collection of timesharing and interactive computers, including an operational PDP-10 (KL-10)

- Empire for the PDP-10 (zip file of FORTRAN-10 source code download) from Classic Empire

- PDP-10 software archive at Trailing Edge

- Computer World ad for Personal Mainframe

Newsgroups

Digital Equipment Corporation computers PDP VAX x86 MIPS Alpha Categories:- DEC hardware

- DEC mainframe computers

- 1968 introductions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.