- Subthalamic nucleus

-

Brain: Subthalamic nucleus

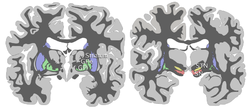

Coronal slices of human brain showing the basal ganglia, subthalamic nucleus (STN) and substantia nigra (SN).

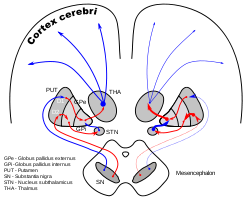

DA-loops in Parkinson's disease Latin nucleus subthalamicus Part of Basal ganglia NeuroNames hier-418 MeSH Subthalamic+Nucleus The subthalamic nucleus is a small lens-shaped nucleus in the brain where it is, from a functional point of view, part of the basal ganglia system. Anatomically, it is the major part of subthalamus. As suggested by its name, the subthalamic nucleus is located ventral to the thalamus. It is also dorsal to the substantia nigra and medial to the internal capsule. It was first described by Jules Bernard Luys in 1865,[1] and the term corpus Luysi or Luys' body is still sometimes used.

Contents

Anatomy

Structure

The principal type of neuron found in the subthalamic nucleus has rather long sparsely spiny dendrites.[2][3] The dendritic arborizations are ellipsoid, replicating in smaller dimension the shape of the nucleus.[4] The dimensions of these arborizations (1200,600 and 300 μm) are similar across many species—including rat, cat, monkey and man—which is unusual. However, the number of neurons increases with brain size as well as the external dimensions of the nucleus. The principal neurons are glutamatergic, which give them a particular functional position in the basal ganglia system. In humans there are also a small number (about 7.5%) of GABAergic interneurons that participate in the local circuitry; however, the dendritic arborizations of subthalamic neurons shy away from the border and majorly interact with one another.[5]

Afferent axons

The subthalamic nucleus receives its main input from the globus pallidus,[6] not so much through the ansa lenticularis as often said but by radiating fibers crossing the medial pallidum first and the internal capsule (see figure). These afferents are GABAergic, inhibiting neurons in the subthalamic nucleus. Excitatory, glutamatergic inputs come from the cerebral cortex (particularly the motor cortex), and from the pars parafascicularis of the central complex. The subthalamic nucleus also receives neuromodulatory inputs, notably dopaminergic axons from the substantia nigra pars compacta.[7] It also receives inputs from the pedunculopontine nucleus.

Efferent targets

The axons of subthalamic nucleus neurons leave the nucleus dorsally. The efferent axons are glutamatergic (excitatory). Except for the connection to the striatum (17.3% in macaques), most of the subthalamic principal neurons are multitargets and directed to the other elements of the core of the basal ganglia.[8] Some send axons to the substantia nigra medially and to the medial and lateral nuclei of the pallidum laterally (3-target, 21.3%). Some are 2-target with the lateral pallidum and the substantia nigra (2.7%) or the lateral pallidum and the medial (48%). Less are single target for the lateral pallidum. In the pallidum, subthalamic terminals end in bands parallel to the pallidal border.[9][10] When all axons reaching this target are added, the main afference of the subthalamic nucleus is, in 82.7% of the cases, clearly the medial pallidum (internal segment of the globus pallidus).

Some researchers have reported internal axon collaterals.[11] However, there is little functional evidence for this.

Physiology

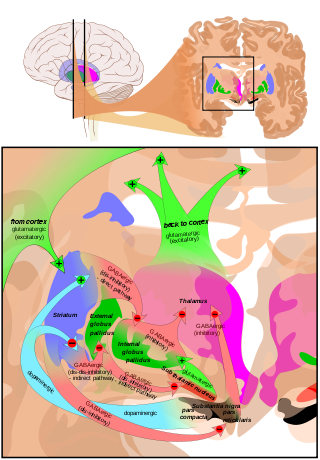

Anatomical overview of the main circuits of the basal ganglia. Subthalamic nucleus is shown in red. Picture shows 2 coronal slices that have been superimposed to include the involved basal ganglia structures. + and - signs at the point of the arrows indicate respectively whether the pathway is excitatory or inhibitory in effect. Green arrows refer to excitatory glutamatergic pathways, red arrows refer to inhibitory GABAergic pathways and turquoise arrows refer to dopaminergic pathways that are excitatory on the direct pathway and inhibitory on the indirect pathway.

Anatomical overview of the main circuits of the basal ganglia. Subthalamic nucleus is shown in red. Picture shows 2 coronal slices that have been superimposed to include the involved basal ganglia structures. + and - signs at the point of the arrows indicate respectively whether the pathway is excitatory or inhibitory in effect. Green arrows refer to excitatory glutamatergic pathways, red arrows refer to inhibitory GABAergic pathways and turquoise arrows refer to dopaminergic pathways that are excitatory on the direct pathway and inhibitory on the indirect pathway.

Subthalamic nucleus

The first intracellular electrical recordings of subthalamic neurons were performed using sharp electrodes in a rat slice preparation.[citation needed] In these recordings three key observations were made, all three of which have dominated subsequent reports of subthalamic firing properties. The first observation was that, in the absence of current injection or synaptic stimulation, the majority of cells were spontaneously firing. The second observation is that these cells are capable of transiently firing at very high frequencies. The third observation concerns non-linear behaviors when cells are transiently depolarized after being hyperpolarized below –65mV. They are then able to engage voltage-gated calcium and sodium currents to fire bursts of action potentials.

Several recent studies have focused on the autonomous pacemaking ability of subthalamic neurons. These cells are often referred to as "fast-spiking pacemakers",[12] since they can generate spontaneous action potentials at rates of 80 to 90 Hz in primates.

Lateropallido-subthalamic system

Strong reciprocal connections link the subthalamic nucleus and the external segment of the globus pallidus. Both are fast-spiking pacemakers. Together, they are thought to constitute the "central pacemaker of the basal ganglia"[13] with synchronous bursts.

The connection of the lateral pallidum with the subthalamic nucleus is also the one in the basal ganglia system where the reduction between emitter/receiving elements is likely the strongest. In terms of volume, in humans, the lateral pallidum measures 808 mm³, the subthalamic nucleus only 158 mm³.[14] This translated in numbers of neurons represents a strong compression with loss of map precision.

Some axons from the lateral pallidum go to the striatum.[15] The activity of the medial pallidum is influenced by afferences from the lateral pallidum and from the subthalamic nucleus.[16] The same for the nigra reticulata.[10] The subthalamic nucleus sends axons to another regulator: the pedunculo-pontine complex (id).

The lateropallido-subthalamic system is thought to play a key role in the generation of the patterns of activity seen in Parkinson's disease.[17]

Pathophysiology and interventions

Chronic stimulation of the STN, called deep brain stimulation (DBS), is used to treat patients with Parkinson disease. The first to be stimulated are the terminal arborisations of afferent axons which modifies the activity of subthalamic neurons. However, it has been shown in thalamic slices from mice,[18] that the stimulus also causes nearby astrocytes to release Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP), a precursor to adenosine (through a catabolic process). In turn, adenosine A1 receptor activation depresses excitatory transmission in the thalamus, thus mimicking ablation of the subthalamic nucleus.

Pathology

Unilateral destruction or disruption of the subthalamic nucleus – which can commonly occur via a small vessel stroke in patients with diabetes, hypertension, or a history of smoking – produces hemiballismus.

Function

The function of the STN is unknown, but current theories place it as a component of the basal ganglia control system which may perform action selection. STN dysfunction has also been shown to increase impulsivity in individuals presented with two equally rewarding stimuli.[19]

Additional images

See also

- Primate basal ganglia

References

- ^ Luys, Jules Bernard (1865) (in French). Recherches sur le système cérébro-spinal, sa structure, ses fonctions et ses maladies. Paris: Baillière.

- ^ Afsharpour, S. (1985). "Light microscopic analysis of Golgi-impregnated rat subthalamic neurons". Journal of Comparative Neurology 236 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1002/cne.902360102. PMID 4056088.

- ^ Rafols, J. � A.; Fox, Clement A. (1976). "The neurons in the primate subthalamic nucleus: a Golgi and electron microscopic study". Journal of Comparative Neurology 168 (1): 75–111. doi:10.1002/cne.901680105. PMID 819471.

- ^ Yelnik, J. & Percheron, G. (1979). "Subthalamic neurons in primates : a quantitative and comparative anatomy". Neuroscience 4 (11): 1717–1743. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(79)90030-7. PMID 117397.

- ^ Levesque J.C. & Parent A. (2005). "GABAergic interneurons in human subthalamic nucleus". Movement Disorders 20 (5): 574–584. doi:10.1002/mds.20374. PMID 15645534.

- ^ Canteras NS, Shammah-Lagnado SJ, Silva BA, Ricardo JA (April 1990). "Afferent connections of the subthalamic nucleus: a combined retrograde and anterograde horseradish peroxidase study in the rat". Brain Res. 513 (1): 43–59. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(90)91087-W. PMID 2350684.

- ^ Cragg S.J.; Baufreton J.; Xue Y.; Bolam J.P.; & Bevan M.D. (2004). "Synaptic release of dopamine in the subthalamic nucleus". European Journal of Neuroscience 20 (7): 1788–1802. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03629.x. PMID 15380000.

- ^ Nauta HJ, Cole M (July 1978). "Efferent projections of the subthalamic nucleus: an autoradiographic study in monkey and cat". J. Comp. Neurol. 180 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1002/cne.901800102. PMID 418083.

- ^ Nauta, H.J.W. & Cole, M. (1978). "Efferent projections of the subthalamic nucleus : an autoradiographic study in monkey and cat". Journal of Comparative Neurology 180 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1002/cne.901800102. PMID 418083.

- ^ a b Smith, Y.; Hazrati, L-N. & Parent, A. (1990). "Efferent projections of the subthalamic nucleus in the squirrel monkey as studied by the PHA-L anterograde tracing method". Journal of Comparative Neurology 294 (2): 306–323. doi:10.1002/cne.902940213. PMID 2332533.

- ^ Kita, H.; Chang, H.T.; & Kitai, S.T. (1983). "The morphology of intracellularly labeled rat subthalamic neurons: A light microscopic analysis". Neuroscience 215 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1002/cne.902150302. PMID 6304154.

- ^ Surmeier D.J.; Mercer J.N.; & Chan C.S. (2005). "Autonomous pacemakers in the basal ganglia: who needs excitatory synapses anyway?". Current Opinion in Neurobiology 15 (3): 312–318. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.007. PMID 15916893.

- ^ Plenz, D. & Kitai, S.T. (1999). "A basal ganglia pacemaker formed by the subthalamic nucleus and external globus pallidus". Nature 400 (6745): 677–682. doi:10.1038/23281. PMID 10458164.

- ^ Yelnik, J. (2002). "Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia". Movement Disorders 17 (Suppl. 3): S15–S21. doi:10.1002/mds.10138. PMID 11948751.

- ^ Sato, F.; Lavallée, P.; Levesque, M. & Parent, A. (2000). "Single-axon tracing study of neurons of the external segment of the globus pallidus in primate". Journal of Comparative Neurology 417 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(20000131)417:1<17::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 10660885.

- ^ Smith, Y.; Wichmann, T. & DeLong, M.R. (1994). "Synaptic innervation of neurones in the internal pallidal segment by the subthalamic nucleus and the external pallidum in monkeys". Journal of Comparative Neurology 343 (2): 297–318. doi:10.1002/cne.903430209. PMID 8027445.

- ^ Bevan M.D.; Magill P.J.; Terman D.; Bolam J.P.; & Wilson CJ. (2002). "Move to the rhythm: oscillations in the subthalamic nucleus-external globus pallidus network". Trends in Neurosciences 25 (10): 525–531. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02235-X. PMID 12220881.

- ^ Bekar L., Libionka W., Tian G., Xu Q., Torres A., Wang X., Lovatt D., Williams E., Takano T., Schnermann J., Bakos R., Nedergaard M. (2008). "Adenosine is crucial for deep brain stimulation–mediated attenuation of tremor". Nature Medicine 14 (1): 75–80. doi:10.1038/nm1693. PMID 18157140.

- ^ Frank, M.; Samanta, J.; Moustafa, A.; Sherman, S. (2007). "Hold Your Horses: Impulsivity, Deep Brain Stimulation, and Medication in Parkinsonism". Science 318 (5854): 1309–12. doi:10.1126/science.1146157. PMID 17962524.

External links

Brain and spinal cord: neural tracts and fasciculi Sensory/

ascending1°: Pacinian corpuscle/Meissner's corpuscle → Gracile fasciculus/Cuneate fasciculus → Gracile nucleus/Cuneate nucleus

2°: → sensory decussation/arcuate fibers (Posterior external arcuate fibers, Internal arcuate fibers) → Medial lemniscus/Trigeminal lemniscus → Thalamus (VPL, VPM)

3°: → Posterior limb of internal capsule → Postcentral gyrusFast/lateral1° (Free nerve ending → A delta fiber) → 2° (Anterior white commissure → Lateral and Anterior Spinothalamic tract → Spinal lemniscus → VPL of Thalamus) → 3° (Postcentral gyrus) → 4° (Posterior parietal cortex)

2° (Spinotectal tract → Superior colliculus of Midbrain tectum)Slow/medial1° (Group C nerve fiber → Spinoreticular tract → Reticular formation) → 2° (MD of Thalamus) → 3° (Cingulate cortex)Motor/

descendingPyramidalflexion: Primary motor cortex → Genu of internal capsule → Corticobulbar tract → Facial motor nucleus → Facial muscles

flexion: Red nucleus → Rubrospinal tract

extension: Vestibulocerebellum → Vestibular nuclei → Vestibulospinal tract

extension: Vestibulocerebellum → Reticular formation → Reticulospinal tract

Midbrain tectum → Tectospinal tract → muscles of neckdirect: 1° (Motor cortex → Striatum) → 2° (GPi) → 3° (Lenticular fasciculus/Ansa lenticularis → Thalamic fasciculus → VL of Thalamus) → 4° (Thalamocortical radiations → Supplementary motor area) → 5° (Motor cortex)

indirect: 1° (Motor cortex → Striatum) → 2° (GPe) → 3° (Subthalamic fasciculus → Subthalamic nucleus) → 4° (Subthalamic fasciculus → GPi) → 5° (Lenticular fasciculus/Ansa lenticularis → Thalamic fasciculus → VL of Thalamus) → 6° (Thalamocortical radiations → Supplementary motor area) → 7° (Motor cortex)

nigrostriatal pathway: Pars compacta → StriatumCerebellar AfferentVestibular nucleus → Vestibulocerebellar tract → ICP → Cerebellum → Granule cell

Pontine nuclei → Pontocerebellar fibers → MCP → Deep cerebellar nuclei → Granule cell

Inferior olivary nucleus → Olivocerebellar tract → ICP → Hemisphere → Purkinje cell → Deep cerebellar nucleiEfferentDentate nucleus in Lateral hemisphere/pontocerebellum → SCP → Dentatothalamic tract → Thalamus (VL) → Motor cortex

Interposed nucleus in Intermediate hemisphere/spinocerebellum → SCP → Reticular formation, or → Cerebellothalamic tract → Red nucleus → Thalamus (VL) → Motor cortex

Fastigial nucleus in Flocculonodular lobe/vestibulocerebellum → Vestibulocerebellar tract → Vestibular nucleusUnc. prop.lower limb → 1° (muscle spindles → DRG) → 2° (Posterior thoracic nucleus → Dorsal/posterior spinocerebellar tract → ICP → Cerebellar vermis)

upper limb → 1° (muscle spindles → DRG) → 2° (Accessory cuneate nucleus → Cuneocerebellar tract → ICP → Anterior lobe of cerebellum)lower limb → 1° (Golgi tendon organ) → 2° (Ventral/anterior spinocerebellar tract→ SCP → Cerebellar vermis)

upper limb → 1° (Golgi tendon organ) → 2° (Rostral spinocerebellar tract → ICP → Cerebellum)Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.