- Dendrite

-

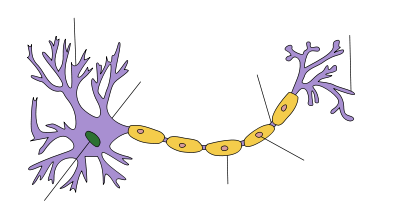

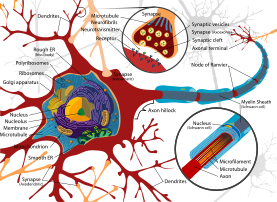

Structure of a typical neuron Dendrite Dendrites (from Greek δένδρον déndron, “tree”) are the branched projections of a neuron that act to conduct the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the neuron from which the dendrites project. Electrical stimulation is transmitted onto dendrites by upstream neurons via synapses which are located at various points throughout the dendritic arbor. Dendrites play a critical role in integrating these synaptic inputs and in determining the extent to which action potentials are produced by the neuron. Recent research has also found that dendrites can support action potentials and release neurotransmitters, a property that was originally believed to be specific to axons.

The long outgrowths on immune system dendritic cells are also called dendrites. These dendrites do not process electrical signals.

Certain classes of dendrites (i.e. Purkinje cells of cerebellum, cerebral cortex) contain small projections referred to as "appendages" or "spines". Appendages increase receptive properties of dendrites to isolate signal specificity. Increased neural activity at spines increases their size and conduction which is thought to play a role in learning and memory formation. There are approximately 200,000 spines per cell, each of which serve as a postsynaptic process for individual presynaptic axons.

Contents

Electrical properties of dendrites

The structure and branching of a neuron's dendrites, as well as the availability and variation in voltage-gated ion conductances, strongly influences how it integrates the input from other neurons, particularly those that input only weakly. This integration is both "temporal" -- involving the summation of stimuli that arrive in rapid succession—as well as "spatial" -- entailing the aggregation of excitatory and inhibitory inputs from separate branches.

Dendrites were once believed to merely convey stimulation passively. In this example, voltage changes measured at the cell body result from activations of distal synapses propagating to the soma without the aid of voltage-gated ion channels. Passive cable theory describes how voltage changes at a particular location on a dendrite transmit this electrical signal through a system of converging dendrite segments of different diameters, lengths, and electrical properties. Based on passive cable theory one can track how changes in a neuron’s dendritic morphology changes the membrane voltage at the soma, and thus how variation in dendrite architectures affects the overall output characteristics of the neuron.

Although passive cable theory offers insights regarding input propagation along dendrite segments, it is important to remember that dendrite membranes are host to a cornucopia of proteins some of which may help amplify or attenuate synaptic input. Sodium, calcium, and potassium channels are all implicated in contributing to input modulation. It is possible that each of these ion species has a family of channel types each with its own biophysical characteristics relevant to synaptic input modulation. Such characteristics include the latency of channel opening, the electrical conductance of the ion pore, the activation voltage, and the activation duration. In this way, a weak input from a distal synapse can be amplified by sodium and calcium currents en route to the soma so that the effects of distal synapse are no less robust than those of a proximal synapse.

One important feature of dendrites, endowed by their active voltage gated conductances, is their ability to send action potentials back into the dendritic arbor. Known as backpropagating action potentials, these signals depolarize the dendritic arbor and provide a crucial component toward synapse modulation and long-term potentiation. Furthermore, a train of backpropagating action potentials artificially generated at the soma can induce a calcium action potential at the dendritic initiation zone in certain types of neurons. Whether or not this mechanism is of physiological importance remains an open question.

Dendrite development

Despite the critical role that dendrites play in the computational tendencies of neurons, very little is known about the process by which dendrites orient themselves in vivo and are compelled to create the intricate branching pattern unique to each specific neuronal class. A balance between metabolic costs of dendritic elaboration and the need to cover receptive field presumably determine the size and shape of dendrites. It is likely that a complex array of extracellular and intracellular cues modulate dendrite development. Transcription factors, receptor-ligand interactions, various signaling pathways, local translational machinery, cytoskeletal elements, Golgi outposts and endosomes have been identified as contributors to the organization of dendrites of individual neurons and the placement of these dendrites in the neuronal circuitry. Important transcription factors involved in the dendritic morphogenesis includes CUT, Abrupt, Collier, Spineless, ACJ6/drifter, CREST, NEUROD1, CREB, NEUROG2 etc[citation needed]. Secreted proteins and cell surface receptors includes neurotrophins and tyrosine kinase receptors, BMP7, Wnt/dishevelled, EPHB 1-3, Semaphorin/plexin-neuropilin, slit-robo, netrin-frazzled, reelin. Rac, CDC42 and RhoA serve as cytoskeletal regulators and the motor protein includes KIF5, dynein, LIS1. Important secretory and endocytic pathways controlling the dendritic development includes DAR3 /SAR1, DAR2/Sec23, DAR6/Rab1 etc. All these molecules interplay with each other in controlling dendritic morphogenesis including the acquisition of type specific dendritic arborization, the regulation of dendrite size and the organization of dendrites emanating from different neurons.

See also

- Dendritic spine

- Axon

- Synapse

- Purkinje cell

- Pyramidal neuron

References

- Kandel, E. R.; Schwartz, J. H.; Jessell, T. M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0838577016.

- Koch, C. (1999). Biophysics of Computation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195104919.

- Stuart, G.; Spruston, N.; Hausser, M. (2008). Dendrites. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198566565. http://www.dendrite.org/book.html.

- Yuh-Nung Jan & Lily Yeh Jan (2010). "Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization". Nature Review Neuroscience 11 (5): 316–328. doi:10.1038/nrn2836. PMC 3079328. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3079328.

External links

- Histology at OU 3_09 - "Slide 3 Spinal cord"

- Dendritic Tree - Cell Centered Database

- Stereo images of dendritic trees in Kryptopterus electroreceptor organs

Histology: nervous tissue (TA A14, GA 9.849, TH H2.00.06, H3.11) CNS GeneralGrey matter · White matter (Projection fibers · Association fiber · Commissural fiber · Lemniscus · Funiculus · Fasciculus · Decussation · Commissure) · meningesOtherPNS GeneralPosterior (Root, Ganglion, Ramus) · Anterior (Root, Ramus) · rami communicantes (Gray, White) · Autonomic ganglion (Preganglionic nerve fibers · Postganglionic nerve fibers)Myelination: Schwann cell (Neurolemma, Myelin incisure, Myelin sheath gap, Internodal segment)

Satellite glial cellNeurons/

nerve fibersPartsPerikaryon (Axon hillock)

Axon (Axon terminals, Axoplasm, Axolemma, Neurofibril/neurofilament)

Dendrite (Nissl body, Dendritic spine, Apical dendrite/Basal dendrite)TypesGSA · GVA · SSA · SVA

fibers (Ia, Ib or Golgi, II or Aβ, III or Aδ or fast pain, IV or C or slow pain)GSE · GVE · SVE

Upper motor neuron · Lower motor neuron (α motorneuron, γ motorneuron, β motorneuron)Termination SynapseCategories:- Neurons

- Neurophysiology

- Cellular neuroscience

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.