- Croatian War of Independence

-

Croatian War of Independence Part of the Yugoslav Wars

Clockwise from top left: The central street of Dubrovnik, the Stradun, in ruins during the Siege of Dubrovnik; the damaged Vukovar water tower, a symbol of the early conflict, flying the Croatian tricolour; soldiers of the Croatian Army getting ready to destroy a Serbian tank; the Vukovar Memorial Cemetery; a Serbian T-55 tank destroyed on the road to DrnišDate March 1991 – November 1995[A 1] Location Croatia[A 2] Result Croatian victory - Croatian forces regain control over most of RSK-held Croatian territory;

- Croatian advances in Bosnia and Herzegovina lead to the eventual end of the Bosnian War.

Territorial

changesThe Croatian government gains control over the vast majority of Croatian territory previously held by rebel Serbs, with the remainder coming under UNTAES control.[A 3] Belligerents  Serbian Krajina[A 4]

Serbian Krajina[A 4]

Yugoslav People's Army (controlled by

Yugoslav People's Army (controlled by  Serbia)[A 5]

Serbia)[A 5]

(1991–92) Republika Srpska[A 6]

Republika Srpska[A 6]

(1992–95) Croatia[A 7]

Croatia[A 7]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[A 8]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[A 8]

(1995)Commanders and leaders

Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević

Milan Babić

Milan Babić

Milan Martić

Milan Martić

Goran Hadžić

Goran Hadžić

Mile Mrkšić

Mile Mrkšić

Veljko Kadijević

Veljko Kadijević

Ratko Mladić

Ratko Mladić

Jovica Stanišić

Jovica Stanišić Franjo Tuđman

Franjo Tuđman

Gojko Šušak

Gojko Šušak

Anton Tus

Anton Tus

Janko Bobetko

Janko Bobetko

Zvonimir Červenko

Zvonimir Červenko

Atif Dudaković

Atif DudakovićCasualties and losses Serbian sources: International sources

Croatian sources:[25][26] - 13,583 killed or missing (10,668 confirmed killed, 2,915 missing)

- 37,180 wounded

or

- 12,000+ killed or missing[27]

or

UNHCR:

- 247,000 Croats and non-Serbs displaced[23]

by Oct. 1993

about 20,000[29][30][31][32] killed on both sides Croatian War

of Independence- Log Revolution

- Pakrac

- Plitvice Lakes

- Borovo Selo

- May 1991

- Coast-91

- Opera Orientalis

- Dalj

- Osijek

- Vukovar

- (Battle

- Massacre)

- Šibenik

- The Barracks

- Banski dvori

- Široka Kula

- Dalmatian channels

- Dubrovnik

- Lovas

- Gospić

- Saborsko

- Baćin

- Otkos 10

- Škabrnja

- Erdut

- Orkan 91

- Voćin

- Vihor

- Joševica

- Bruška

- Miljevci

- Tigar

- Maslenica

- Medak Pocket

- Winter '94

- Flash

- Zagreb

- Summer '95

- Storm

- Maestral

- Timeline of all major events

- Events in Serbia

The Croatian War of Independence was fought from 1991 to 1995 between forces loyal to the government of Croatia—which had declared independence from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFR Yugoslavia)—and the Serb-controlled Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and local Serb forces, with the JNA ending its combat operations in Croatia by 1992. In Croatia, the war is primarily referred to as the Homeland War (Domovinski rat) and also as the Greater-Serbian aggression (Velikosrpska agresija).[33][34] In Serbian sources, War in Croatia (Rat u Hrvatskoj) is the most commonly used term.[35]

Initially, the war was waged between Croatian police forces and Serbs living in the Republic of Croatia. As the JNA came under increasing Serbian influence in Belgrade, many of its units began assisting the Serbs fighting in Croatia.[36] The Croatian side aimed to establish a sovereign country independent of Yugoslavia, and the Serbs, supported by Serbia,[37][38] opposed the secession and wanted Croatia to remain a part of Yugoslavia. The Serbs effectively sought new boundaries in areas of Croatia with a Serb majority or significant minority,[39][40] and attempted to conquer as much of Croatia as possible.[41][42] The goal was primarily to remain in the same state with the rest of the Serbian nation, which was seen as an attempt to form a "Greater Serbia" by Croats (and Bosniaks).[43] In 2007, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) returned a guilty verdict against Milan Martić, one of Serb leaders in Croatia, stating that he colluded with Slobodan Milošević and others to create a "unified Serbian state".[44] In 2011 the ICTY ruled that Croatian generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were a part of a joint criminal enterprise of the military and political leadership of Croatia whose goal was to drive Krajina Serbs out of Croatia in August 1995 and repopulate the area with Croatian refugees.[45]

At the beginning of the war, the JNA tried to forcefully keep Croatia in Yugoslavia by occupying the whole of Croatia.[46][47] After they failed to do this, Serbian forces established the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) within Croatia. By the end of 1991, most of Croatia was gravely affected by war, with numerous cities and villages heavily damaged in combat operations,[48] and the rest supporting hundreds of thousands of refugees.[49] After the ceasefire of January 1992 and international recognition of the Republic of Croatia as a sovereign state,[50][51] the front lines were entrenched, United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed,[52] and combat became largely intermittent in the following three years. During that time, the RSK encompassed 13,913 square kilometers (5,372 sq mi), more than a quarter of Croatia.[53] In 1995, Croatia launched two major offensives known as Operation Flash and Operation Storm,[3][54] which would effectively end the war in its favor. The remaining United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) zone was peacefully reintegrated into Croatia by 1998.[4][8]

The war ended with a total Croatian victory, as Croatia achieved the goals it had declared at the beginning of the war: independence and preservation of its borders.[3][4] However, much of Croatia was devastated, with estimates ranging from 21–25% of its economy destroyed and an estimated USD $37 billion in damaged infrastructure, lost output, and refugee-related costs.[55] The total number of deaths on both sides was around 20,000,[29] and there were refugees displaced on both sides at some point: Croats mostly at the beginning of the war, and Serbs mostly at the end. While many people returned, and Croatia and Serbia progressively cooperated more with each other on all levels, some ill will remains because of verdicts by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and lawsuits filed against each other.[56][57]

Background

See also: Timeline of Yugoslavian breakupRise of nationalism in Yugoslavia

Croatia Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia Serbia and Montenegro Republic of Srpska Republic of Serbian Krajina Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia Macedonia Slovenia

Croatia Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia Serbia and Montenegro Republic of Srpska Republic of Serbian Krajina Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia Macedonia Slovenia See also: Anti-bureaucratic revolution, Gazimestan speech, and Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

See also: Anti-bureaucratic revolution, Gazimestan speech, and Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and ArtsThe war in Croatia resulted from the rise of nationalism in the 1980s which slowly led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia. A crisis emerged in Yugoslavia with the weakening of the Communist states in Eastern Europe towards the end of the Cold War, as symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In Yugoslavia, the national communist party, officially called the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, had lost its ideological potency.[58]

In the 1980s, Albanian secessionist movements in the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, Socialist Republic of Serbia, led to the repression of the Albanian majority in Serbia's southern province.[59] The more prosperous republics of SR Slovenia and SR Croatia wanted to move towards decentralization and democracy.[60] Serbia, headed by Slobodan Milošević, adhered to centralism and single-party rule through the Yugoslav Communist Party. Milošević effectively ended the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina autonomous provinces.[38][59][61][62]

As Slovenia and Croatia began to seek greater autonomy within the federation, including confederate status and even full independence, the nationalist ideas started to grow within the ranks of the still-ruling League of Communists. As Milošević rose to power in Serbia, his speeches favored continuation of a unified Yugoslav state—one in which all power would be centralized in Belgrade.[63] In the Gazimestan speech, delivered on June 28, 1989, he remarked on the current "battles and quarrels", saying that even though there were currently no armed battles, the possibility could not be excluded yet.[64] The general political situation grew more tense when future Serbian Radical Party president Vojislav Šešelj visited the United States in 1989, and was later awarded the honorary title of "Vojvoda" (duke) by Momčilo Đujić, a World War II Chetnik leader, during a commemoration of the Battle of Kosovo.[65] Years later, Croatian Serb leader Milan Babić testified that Momčilo Đujić had financially supported the Serbs in Croatia in the 1990s.[66]

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after the adoption of amendments to the Serbian constitution that allowed the Serbian republic's government to re-assert effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Up until that time, a number of political decisions were legislated from within these provinces, and they had a vote on the Yugoslav federal presidency level (six members from the republics and two members from the autonomous provinces).[67] Serbia, under President Slobodan Milošević, gained control over three out of eight votes in the Yugoslav presidency, and this was used on May 16, 1991, when the Serbian parliament exchanged Riza Sapunxhiu and Nenad Bućin, representatives of Kosovo and Vojvodina, for Jugoslav Kostić and Sejdo Bajramović.[68] The fourth vote was provided by Montenegro, whose government survived a coup d'état in October 1988,[69] but not a second one in January 1989.[70] Once Serbia secured four out of eight federal presidency votes, it was able to heavily influence decision-making at the federal level, because unfavorable decisions could be blocked; this rendered the governing body ineffective. This situation led to objections from other republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia) and calls for reform of the Yugoslav Federation.[71]

Electoral and constitutional moves

See also: Croatian parliamentary election, 1990The weakening of the communist regime allowed nationalism to spread its political presence, even within the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In 1989, political parties were allowed and a number of them had been founded, including the Croatian Democratic Union (Croatian: Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica) (HDZ), led by Franjo Tuđman, who later became the first president of Croatia.[72] Tuđman made international visits during the late 1980s to garner support from the Croatian diaspora for the Croatian national cause.[73]

In January 1990, the League of Communists broke up on the lines of the individual republics. At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, on January 20, 1990, the delegations of the republics could not agree on the main issues in the Yugoslav federation. The Croatian and Slovenian delegations demanded a looser federation, while the Serbian delegation, headed by Milošević, opposed this. As a result, the Slovenian and Croatian delegates left the Congress.[74][75]

Presidents Franjo Tuđman and Milan Kučan led the new generation of people who wanted Croatia and Slovenia to disengage from Yugoslavia and turn towards free market and democratic reforms

Presidents Franjo Tuđman and Milan Kučan led the new generation of people who wanted Croatia and Slovenia to disengage from Yugoslavia and turn towards free market and democratic reformsIn February 1990, Jovan Rašković founded the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) in Knin. Its program stated that the "regional division of Croatia is outdated" and that it "does not correspond with the interest of Serb people".[76] The party program endorsed redrawing regional and municipal lines to reflect the ethnic composition of the areas, and asserted the right of territories with a "special ethnic composition" to become autonomous. This echoed Milošević position that internal Yugoslav borders should be redrawn to permit all Serbs to live in a single country.[40] Prominent members of the SDS were Milan Babić and Milan Martić, both of whom later became high-ranking Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) officials. During his later trial, Babić would testify that there was a media campaign directed from Belgrade that portrayed the Serbs in Croatia as being threatened with genocide by the Croat majority and that he fell prey to the propaganda.[77] On March 4, 1990, a meeting of 50,000 Serbs was held at Petrova Gora. People at the rally shouted negative remarks aimed at Tuđman and other Croatians,[76] chanted "This is Serbia",[76] and expressed support for Milošević.[78][79]

The first free elections in Croatia and Slovenia were scheduled for a few months later.[80] The first round of elections in Croatia were held on April 22, and the second round on May 6.[81] The HDZ based its campaign on an aspiration for greater sovereignty for Croatia and on a platform opposed to Yugoslav unitarist ideology, fueling a sentiment among Croats that "only the HDZ could protect Croatia from the aspirations of Serbian elements led by Slobodan Milošević towards a Greater Serbia". It topped the poll in the elections (followed by Ivica Račan's reformed communists, Social Democratic Party of Croatia) and was set to form a new Croatian Government.[81]

A tense atmosphere prevailed in 1990, and especially so during the period immediately before the elections. On May 13, 1990, a football game was held in Zagreb between Zagreb's Dinamo team and Belgrade's Crvena Zvezda team. The game erupted into violence between football fans and police.[82]

On May 30, 1990, the new Croatian Parliament held its first session. President Tuđman announced his manifesto for a new Constitution (ratified at the end of the year) and a multitude of political, economic, and social changes, notably to what extent minority rights (mainly for Serbs) would be guaranteed. Local Serb politicians opposed the new constitution on the grounds that the local Serb population would be threatened. Their prime concern was that a new constitution would not henceforth designate Croatia a "national state of the Croatian people, a state of the Serbian people, and any other people living in it" but a "national state of the Croatian people and any people living in it".[83] In 1991, Serbs represented 12.2 percent of the total population of Croatia, but they held a disproportionate number of official posts: 17.7 percent of appointed officials in Croatia, including police, were Serbs. An even greater proportion of those posts had been held by Serbs in Croatia earlier on, which created a perception that the Serbs were guardians of the communist regime.[84] After HDZ came to power, some of the Serbs employed in public administration, especially the police, lost their jobs and were replaced by Croats.[85]

According to the 1991 census, the percentage of those declaring themselves as Serb was 12%; 78% of the population declared itself as Croat. On December 22, 1990, the Parliament of Croatia ratified the new constitution, which changed the status of Serbs in Croatia from a "constituent nation" to a "national minority".[86] This was read as taking away some of the rights that Serbs had been granted by the previous Socialist constitution, and fueled extremism among the Serbs of Croatia.[87] However, the constitution defined Croatia as "the national state of the Croatian nation and a state of members of other nations and minorities who are its citizens: Serbs... who are guaranteed equality with citizens of Croatian nationality...."[83]

Civil unrest and demands for autonomy

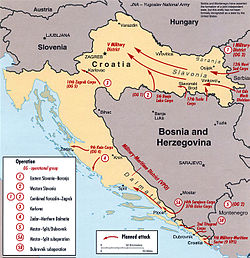

See also: Log Revolution Map of the strategic offensive plan of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) in 1991 as interpreted by the US Central Intelligence Agency

Map of the strategic offensive plan of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) in 1991 as interpreted by the US Central Intelligence Agency

The Serbs within Croatia did not initially seek independence before 1990. On July 25, 1990, a Serbian Assembly was established in Srb, north of Knin, as the political representation of the Serbian people in Croatia. The Serbian Assembly declared "sovereignty and autonomy of the Serb people in Croatia".[83] On December 21, 1990, the SAO Krajina was proclaimed by the municipalities of the regions of Northern Dalmatia and Lika, in south-western Croatia. Article 1 of the Statute of the SAO Krajina defined the SAO Krajina as "a form of territorial autonomy within the Republic of Croatia" in which the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia, state laws, and the Statute of the SAO Krajina were applied.[83][88]

Following Tuđman's election and the perceived threat from the new constitution,[86] Serb nationalists in the Kninska Krajina region began taking armed action against Croatian government officials. Many were forcibly expelled or excluded from the SAO Krajina. Croatian government property throughout the region was increasingly controlled by local Serb municipalities or the newly established "Serbian National Council". This would later become the government of the breakaway Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK).[83]

In August 1990, an unrecognized mono-ethnic referendum was held in regions with a substantial Serb population which would later become known as the RSK (bordering western Bosnia and Herzegovina) on the question of Serb "sovereignty and autonomy" in Croatia.[89] This was an attempt to counter the changes in the constitution. The Croatian government tried to block the referendum by sending police forces to police stations in Serb-populated areas to seize their weapons. Among other incidents, local Serbs from the southern hinterlands of Croatia, mostly around the city of Knin, blocked roads to tourist destinations in Dalmatia. This incident is known as the "Log revolution".[90][91] Years later, during Milan Martić's trial, Milan Babić would claim that he was tricked by Martić into agreeing to the Log Revolution, and that it and the entire war in Croatia was Martić's responsibility, and had been orchestrated by Belgrade.[92] The statement was corroborated by Martić in an interview published in 1991.[93] Babić confirmed that by July 1991 Milošević had taken over control of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA).[94] The Croatian government responded to the blockade of roads by sending special police teams in helicopters to the scene, but they were intercepted by SFR Yugoslav Air Force fighter jets and forced to turn back to Zagreb. The Serbs felled pine trees or used bulldozers to block roads to seal off towns like Knin and Benkovac near the Adriatic coast. On August 18, 1990, the Serbian newspaper Večernje novosti said almost "two million Serbs were ready to go to Croatia to fight".[90]

Immediately after the Slovenian referendum on independence and the new Croat constitution, the JNA announced that a new defense doctrine would apply across the country. The Josip Broz Tito-era doctrine of "general people's defense", in which each republic maintained a Territorial defense force (Croatian: Teritorijalna obrana) (TO), would henceforth be replaced by a centrally-directed system of defense. The republics would lose their role in defense matters and their TOs would be disarmed and subordinated to JNA headquarters in Belgrade.[95] In the case of the Croatian TO force, this meant little, as the JNA had already confiscated Croatian TO weapons in May 1990, in the wake of the Croatian parliamentary elections.[96] An ultimatum was issued requesting disarming and disbanding of military forces considered illegal by the Yugoslav authorities. Since the original ultimatum did not specify which forces were considered illegal, the central Yugoslav authorities soon clarified that the request was actually aimed at official Croatian armed forces.[97][98] Croatian authorities refused to comply, and the Yugoslav army withdrew the ultimatum six days after it was issued.[99][100]

Military forces

Serbian forces

See also: Yugoslav People's Army and Military of Serbian KrajinaThe JNA was initially formed during World War II to carry out guerrilla warfare against occupying Axis forces. The success of the Partisan movement led to the JNA basing much of its operational strategy on guerrilla warfare, as its plans normally entailed defending against NATO or Warsaw Pact attacks, where other types of warfare would put the JNA in a comparatively poor position. That approach led to maintenance of a Territorial Defense system.[101]

On paper, the JNA seemed a powerful force, with 2,000 tanks and 300 jet aircraft (all either Soviet or locally produced). However, by 1991, the majority of this equipment was 30 years old, as the force consisted primarily of T-54/55 tanks and MiG-21 aircraft.[102] Still, the JNA operated around 300 M-84 tanks (a Yugoslav version of the Soviet T-72) and a sizable fleet of ground-attack aircraft, such as the Soko G-4 Super Galeb and the Soko J-22 Orao, whose armament included AGM-65 Maverick guided missiles.[103] By contrast, more modern cheap anti-tank missiles (like the AT-5) and anti-aircraft missiles (like the SA-14) were abundant and were designed to destroy much more advanced weaponry. Before the war the JNA had 169,000 regular troops, including 70,000 professional officers. The fighting in Slovenia brought about a great number of desertions, and the army responded by mobilizing Serbian reserve troops. Approximately 100,000 evaded the draft, and the new conscripts proved an ineffective fighting force. The JNA resorted to reliance on irregular militias.[104] Paramilitary units like White Eagles, Serbian Guard, Dušan Silni, and Serb Volunteer Guard, which committed a number of massacres against Croat and other non-Serbs civilians, were increasingly used by the Yugoslav and Serb forces.[105][106] In addition, there were foreign fighters supporting the RSK, most of them from Russia.[107] With the retreat of the JNA forces in 1992, JNA units were reorganized as the Army of Serb Krajina, which was a direct heir to the JNA organization, with little improvement.[11][108]

By 1991, the JNA officer corps was dominated by Serbs and Montenegrins; they were overrepresented in Yugoslav federal institutions, especially the army. 57.1 percent of JNA officers were Serbs, while only 36.3 percent of population of Yugoslavia were Serbs.[84] A similar structure was observed as early as 1981.[109] Even though the two peoples combined comprised 38.8 percent of population of Yugoslavia, 70 percent of all JNA officers and non-commissioned officers were either Serbs or Montenegrins.[110] In 1991 the JNA was instructed by Slobodan Milošević and Borisav Jović, through the federal defense secretary Kadijević, to "completely eliminate Croats and Slovenes from the army."[111]

Croatian forces

See also: Croatian National Guard and Military of CroatiaThe Croatian military eased their equipment shortage by seizing the JNA barracks in the Battle of the barracks.

The Croatian military was in a much worse state than that of the Serbs. In the early stages of the war, lack of military units meant that the Croatian Police force would take the brunt of the fighting. The Croatian National Guard (Croatian: Zbor narodne garde), the new Croatian military, was formed on April 11, 1991, and gradually developed into the Croatian Army (Croatian: Hrvatska vojska) by 1993.[9] Weaponry was in short supply, and many units were formed either unarmed or with obsolete World War II-era rifles. The Croatian Army had only a handful of tanks, including World War II-surplus vehicles such as the T-34, and its air force was in an even worse state, consisting of only a few Antonov An-2 biplane crop-dusters that had been converted to drop makeshift bombs.[112] However, since the soldiers were defending their homeland and their families, the army was very motivated. They were formed into fighting units that operated in their local areas, and they proved quite effective.[113][114]

In August 1991, the Croatian Army had fewer than 20 brigades. After general mobilization was instituted in October, the size of the army grew to 60 brigades and 37 independent battalions by the end of the year.[115][116] In 1991 and 1992, Croatia was also supported by 456 foreign fighters, most of them British (139), French (69), and German (55).[117] The seizure of the JNA's barracks between September and December helped to alleviate the Croatians' equipment shortage and allowed them to recapture most of the weaponry that the JNA had confiscated from Croatian Territorial Defense Forces depots in 1990. A significant number of heavy weapons were captured, along with the 32nd JNA Corps' entire armory.[118][119][120][121] By 1995, the balance of power had shifted significantly. Serb forces in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were capable of fielding an estimated 130,000 troops; the Croatian Army, Croatian Defence Council (Croatian: Hrvatsko vijeće obrane) (HVO), and the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina could field a combined force of 250,000 soldiers and 570 tanks.[122][123]

Course of the war

See also: Timeline of the Croatian War of Independence1991: Open hostilities begin

First armed incidents

See also: Pakrac clash, Battle of Šibenik (1991), Plitvice Lakes incident, and Borovo Selo killingsA monument to Josip Jović, widely perceived in Croatia as the first Croatian victim of the war, who died during the Plitvice Lakes incident.

Ethnic hatred grew as various incidents fueled the propaganda machines on both sides. During his dissident testimony at the ICTY, one of the top-Krajina leaders Milan Babić stated that the Serb side started using force first.[124]

The conflict escalated into armed incidents in the majority-Serb populated areas. Serbs began a series of attacks on Croatian police units in Pakrac,[1][125] more than 20 people were killed by the end of April. In the same period, nearly 200 incidents involving use of explosive devices and 89 attacks on the Croatian police were recorded.[38] Josip Jović from Aržano is widely reported as the first police officer killed by Serb forces as part of the war, during the Plitvice Lakes incident in late March 1991.[2][126]

In April 1991, the Serbs within Croatia began to make moves to secede from that territory. It is a matter of debate to what extent this move was locally motivated and to what degree the Milošević-led Serbian government was involved. In any event, the Republic of Serbian Krajina was declared, which consisted of any Croatian territory with a substantial Serb population. The Croatian government viewed this move as a rebellion.[83][127][128]

The Croatian Ministry of the Interior started arming an increasing number of special police forces, and this led to the building of a real army. On April 9, 1991, Croatian President Tuđman ordered the special police forces to be renamed Zbor Narodne Garde ("National Guard"); this marks the creation of a separate military of Croatia.[9] The newly-constituted military units were publicly displayed in a military parade and review held at Stadion Kranjčevićeva in Zagreb on May 28, 1991.[129]

On May 15, Stjepan Mesić, a Croat, was scheduled to be the chairman of the rotating presidency of Yugoslavia. Serbia, aided by Kosovo, Montenegro, and Vojvodina, whose presidency votes were at that time under Serbian control, blocked the appointment, which was otherwise seen as largely ceremonial. This maneuver technically left Yugoslavia without a head of state and without a commander-in-chief.[130][131] Two days later, a repeated attempt to vote on the issue failed. Ante Marković, prime minister of Yugoslavia at the time, proposed appointing a panel which would wield presidential powers.[132] It was not immediately clear who the panel members would be, apart from defense minister Veljko Kadijević, nor who would fill position of JNA commander-in-chief. The move was quickly rejected by Croatia as unconstitutional.[133] The crisis was resolved after a six-week stalemate, and Stipe Mesić was elected president—the first non-communist to become Yugoslav head of state in decades.[134] Meanwhile, the federal army, the JNA, and the local Territorial Defense Forces continued to be led by Federal authorities controlled by Milošević. On occasion, the JNA sided with the local Croatian Serb forces.[83] Helsinki Watch reported that Serb Krajina authorities executed Serbs who were willing to reach an accommodation with Croat officials.[38]

Declaration of independence

See also: Croatian independence referendum, 1991 and Ten-Day War93.24% 6.76% For Against On May 19, 1991, the Croatian authorities held a referendum on independence with the option of remaining in Yugoslavia as a looser union.[135][136] Serb local authorities issued calls for a boycott, which were largely followed by Croatian Serbs. The referendum passed with 94% in favor.[137] Croatia declared independence and dissolved (Croatian: razdruženje) its association with Yugoslavia on June 25, 1991.[15][138] The European Community and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe urged Croatian authorities to place a three-month moratorium on the decision.[139] Croatia agreed to freeze its independence declaration for three months, which eased tensions a little.[16]

In June and July 1991, the short armed conflict in Slovenia came to a speedy and fairly peaceful conclusion, partly because of the ethnic homogeneity of the population of Slovenia.[140][141] It was later revealed that a military strike against Slovenia, followed by a planned withdrawal, was conceived by Slobodan Milošević and Borisav Jović, then president of the SFR Yugoslavia presidency. Jović published his diary containing the information and repeated it in his testimony at the Milošević trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).[111] During the war in Slovenia, large numbers of Croatian and Slovenian soldiers refused to fight and deserted from the JNA.[142]

Escalation of the conflict

Further information: Battle of Vukovar, Operation Coast-91, Siege of Dubrovnik, Operation Otkos 10, Battle of the barracks, Gospić massacre, Operation Orkan 91, and Battle of the Dalmatian channels"Croats became refugees in their own country."

Mirko Kovač on the 10th anniversary of the end of the Croatian War of Independence[143] Water tower in Vukovar—a symbol of the early conflict

Water tower in Vukovar—a symbol of the early conflict

In the first stages of war, Croatian cities were extensively shelled by the JNA. Bombardment damage in Dubrovnik: Stradun in the walled city (left) and map of the walled city with the damage marked (right)Milan Martić, August 19, 1991, on the expansion of Republic of Serbian Krajina at Croatia's expense[93]

In the first stages of war, Croatian cities were extensively shelled by the JNA. Bombardment damage in Dubrovnik: Stradun in the walled city (left) and map of the walled city with the damage marked (right)Milan Martić, August 19, 1991, on the expansion of Republic of Serbian Krajina at Croatia's expense[93]In July, in an attempt to salvage what remained of Yugoslavia, the JNA forces were involved in operations against predominantly Croat areas. In July the Serb-led Territorial Defence Forces started their advance on Dalmatian coastal areas in Operation Coast-91.[144] By early August, large areas of Banovina were overrun by Serb forces.[145]

With the start of military operations in Croatia, Croats and a number of Serbian conscripts started to desert the JNA en masse, similar to what had happened in Slovenia.[142][144] Albanians and Macedonians started to search for a way to legally leave the JNA or serve their conscription term in Macedonia; these moves further homogenized the ethnic composition of JNA troops in or near Croatia.[146]

One month after Croatia declared its independence, the Yugoslav army and other Serb forces held something less than one-third of the Croatian territory,[145] mostly in areas with a predominantly ethnic Serb population.[147][148] The Yugoslav and Serbian forces had superiority in weaponry and equipment. Their military strategy partly consisted of extensive shelling, at times irrespective of the presence of civilians.[149] As the war progressed, the cities of Dubrovnik, Gospić, Šibenik, Zadar, Karlovac, Sisak, Slavonski Brod, Osijek, Vinkovci, and Vukovar all came under attack by Yugoslav forces.[150][151][152][153] The United Nations (UN) imposed a weapons embargo; this did not affect JNA-backed Serb forces significantly, as they had the JNA arsenal at their disposal, but it caused serious trouble for the newly-formed Croatian army. The Croatian government started smuggling weapons over its borders.[154][155]

In August 1991, the border city of Vukovar came under attack and the Battle of Vukovar began.[156][157] Eastern Slavonia was gravely impacted throughout this period, starting with the Dalj massacre of August 1991;[158] fronts developed around Osijek and Vinkovci in parallel to the encirclement of Vukovar.[159][160][161][162][163][164]

In September, Serbian troops completely surrounded the city of Vukovar. Croatian troops, including the 204th Vukovar Brigade, entrenched themselves within the city and held their ground against elite armored and mechanized brigades of the JNA,[165] as well as Serb paramilitary units.[105][166][167] Some ethnic Croatian civilians had taken shelter inside the city. Other members of the civilian population fled the area en masse. Death toll estimates for Vukovar as a result of the siege range from 1,798 to 5,000.[106] A further 22,000 were exiled from Vukovar immediately after the town was captured.[168][169]

There is evidence that the population suffered extreme hardship.[113] Some estimates include 220,000 Croats and 300,000 Serbs internally displaced for the duration of the war in Croatia. The 1991 census data and the 1993 RSK population data for the territory of Krajina differ by some 102,000 Serbs and 135,000 Croats. In many areas, large numbers of civilians were forced out by the military. It was at this time that the term ethnic cleansing—the meaning of which ranged from eviction to murder—first entered the English lexicon.[170]

On October 3 the Yugoslav Navy renewed its blockade of the main ports of Croatia. This move followed months of standoff for Yugoslav People's Army positions in Dalmatia and elsewhere now known as the Battle of the barracks. It also coincided with the end of Operation Coast-91, in which the Yugoslav Army failed to occupy the coastline in an attempt to cut off Dalmatia's access to the rest of Croatia.[171]

On October 5 President Tuđman made a speech in which he called upon the whole population to mobilize and defend against "Greater Serbian imperialism" pursued by the Serb-led JNA, Serbian paramilitary formations, and rebel Serb forces.[116] On October 7 the Yugoslav air force attacked the main government building in Zagreb, an incident referred to as the bombing of Banski dvori.[172][173] The next day, as a previously agreed three-month moratorium on implementation of the declaration of independence expired, the Croatian Parliament severed all remaining ties with Yugoslavia. October 8 is now celebrated as Croatia's Independence Day.[17] The bombing of the government offices and the Siege of Dubrovnik that started in October[174] were contributing factors that led to European Union (EU) sanctions against Serbia.[175][176] The international media focused on—and exaggerated—the damage to Dubrovnik's cultural heritage; concerns about civilian casualties and pivotal battles such as the one in Vukovar were pushed out of public view.[177] Nonetheless, artillery attacks on Dubrovnik damaged 56% of its buildings to some degree, as the historic walled city, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, sustained 650 hits by artillery rounds.[178]

Peak of the war

In response to the 5th JNA Corps advance across the Sava River towards Pakrac and further north into western Slavonia,[179] the Croatian army began a successful counterattack in early November 1991, its first major offensive operation of the war. Operation Otkos 10 (October 31 to November 4) resulted in Croatia recapturing an area between the Bilogora and Papuk mountains.[36][180] The Croatian army recaptured approximately 270 square kilometers (100 sq mi) of territory in this operation.[180]

In October and early November, the situation for Croats in Vukovar became ever more desperate as the JNA escalated the war.[48][181] On November 18, 1991, Vukovar fell to the Serbs after a three-month siege, and the Vukovar massacre took place;[182][183] the survivors were transported to prison camps such as Ovčara and Velepromet, with the majority ending up in Sremska Mitrovica prison camp.[184] The city of Vukovar was almost completely destroyed; 15,000 houses were destroyed.[169] During the 87-day battle, the city was struck by 8,000 to 9,000 artillery shells every day,[185] for a total of more than one million rounds.[186] The sustained siege attracted heavy international media attention. Many international journalists were in or near Vukovar, as was UN peace mediator Cyrus Vance, who had been Secretary of State to former US President Carter.[187]

Photos of the victims of the Lovas massacre

Photos of the victims of the Lovas massacre

Rudolf Perešin, a fighter jet pilot who left the Yugoslav People's Army to join the Croatian Army, next to his MiG-21

Rudolf Perešin, a fighter jet pilot who left the Yugoslav People's Army to join the Croatian Army, next to his MiG-21

Also in eastern Slavonia, the Lovas massacre occurred in October[105][188] and the Erdut massacre in November 1991, before and after the fall of Vukovar.[189] At the same time, the Škabrnja massacre occurred in the northern Dalmatian hinterland; it was largely overshadowed by the events at Vukovar.[190]

On November 14, the Navy blockade of Dalmatian ports was challenged by civilian ships. The confrontation culminated in the Battle of the Dalmatian channels, when Croatian coastal and island based artillery damaged, sunk, or captured a number of Yugoslav navy vessels, including Mukos PČ 176, later rechristened PB 62 Šolta.[191] After the battle, the Yugoslav naval operations were effectively limited to the southern Adriatic.[192][193][194]

Croatian forces made further advances in the second half of December, including Operation Orkan 91, but at that point a lasting ceasefire was about to be signed (in January 1992). In the course of Orkan 91, Croatian army recaptured approximately 1,440 square kilometers (560 sq mi) of territory.[180] The end of the operation marked end of a six-month-long phase of intense fighting; 10,000 people had died, hundreds of thousands had fled, and tens of thousands of homes had been destroyed.[195]

On December 19, as the intensity of the fighting increased, Croatia won its first diplomatic recognition by a western nation—Iceland—while the Serbian Autonomous Regions in Krajina and western Slavonia officially declared themselves the Republic of Serbian Krajina.[41] Four days later, Germany recognized Croatian independence.[50] On December 26, 1991, the Serb-dominated federal presidency announced plans for a smaller Yugoslavia that could include the territory captured from Croatia during the war.[43]

In the second half of 1991, all the Croatian democratic parties gathered together to form a unified national government to confront the JNA and Serbian paramilitaries, with Franjo Gregurić as prime minister. Opposition parties filled 16 out of 27 government posts.[9][196] Mediated by foreign diplomats, ceasefires were frequently signed and frequently broken. Croatia lost much territory, but expanded the Croatian Army from the seven brigades it had at the time of the first ceasefire to 60 brigades and 37 independent battalions by December 31, 1991.[115]

The Arbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on the former Yugoslavia, also referred to as Badinter Arbitration Committee, was set up by the Council of Ministers of the European Economic Community (EEC) on August 27, 1991, to provide the Conference on Yugoslavia with legal advice. The five-member Commission consisted of presidents of Constitutional Courts in the EEC. Starting in late November 1991, the committee rendered ten opinions. The Commission stated, among other things, that SFR Yugoslavia was in the process of dissolution and that the internal boundaries of Yugoslav republics may not be altered unless freely agreed upon.[14] Factors in Croatia's preservation of its pre-war borders were the Yugoslav Federal Constitution Amendments of 1971, and the Yugoslav Federal Constitution of 1974. The 1971 amendments introduced a concept that sovereign rights were exercised by the federal units, and that the federation had only the authority specifically transferred to it by the constitution. The 1974 constitution confirmed and strengthened the principles introduced in 1971.[197][198] The borders had been defined by demarcation commissions in 1947, pursuant to decisions of AVNOJ in 1943 and 1945 regarding the federal organization of Yugoslavia.[199]

1992: Ceasefire

"Greater Serbian circles have no interest in protecting the Serbian people living in either Croatia or Bosnia or anywhere else. If that were the case, then we could look and see what it is in the Croatian constitution, see what is in the declaration on minorities, on the Serbs in Croatia and on minorities, because the Serbs are treated separately there. Let us see if the Serbs have less rights than the Croats in Croatia. That would be protecting the Serbs in Croatia. But that is not what is sought. Gentlemen, what they want is territory".

Stjepan Mesić on Belgrade's intentions in the war.[200]See also: United Nations Protection Force and Miljevci plateau incidentA new UN-sponsored ceasefire, the fifteenth one in just six months, was agreed on January 2, 1992, and came into force the next day.[11] On January 7, 1992, JNA pilot Emir Šišić shot down a European Community helicopter in Croatia, killing five truce observers.[201] Croatia was officially recognized by the European Community on January 15, 1992.[50] Even though the JNA began to withdraw from Croatia, including Krajina, the RSK clearly retained the upper hand in the occupied territories due to support from Serbia.[108] By that time, the RSK encompassed 13,913 square kilometers (5,372 sq mi) of territory.[53] The area size did not encompass another 680 square kilometers (260 sq mi) of occupied territory near Dubrovnik, as that area was not considered part of the RSK.[202]

Ending the series of unsuccessful ceasefires, the UN deployed a protection force in Serbian-held Croatia—the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR)—to supervise and maintain the agreement.[203] The UNPROFOR was officially created by UN Security Council Resolution 743 on February 21, 1992.[52] The warring parties mostly moved to entrenched positions, and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated.[11] Croatia became a member of the UN on May 22, 1992, which was conditional upon Croatia amending its constitution to protect the human rights of minority groups and dissidents.[51] Expulsions of the non-Serb civilian population remaining in the occupied territories continued despite the presence of the UNPROFOR peacekeeping troops, and in some cases, with UN troops being virtually enlisted as accomplices.[204]

Croatian soldiers capture a Serb cannon and truck in the Miljevci plateau incident, June 21, 1992

Croatian soldiers capture a Serb cannon and truck in the Miljevci plateau incident, June 21, 1992

The Yugoslav People's Army took thousands of prisoners during the war in Croatia, and interned them in camps in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. The Croatian forces also captured some Serbian prisoners, and the two sides agreed to several prisoner exchanges; most prisoners were freed by the end of 1992. Some infamous prisons included the Sremska Mitrovica camp, the Stajićevo camp, and the Begejci camp in Serbia, and the Morinj camp in Montenegro.[205] The Croatian Army also established detention camps, such as the Lora prison camp in Split.[205]

Armed conflict in Croatia continued intermittently on a smaller scale. There were several smaller operations undertaken by Croatian forces to relieve the siege of Dubrovnik, and other Croatian cities (Šibenik, Zadar and Gospić) from Krajina forces. Battles included the Miljevci plateau incident (between Krka and Drniš), on June 21–22, 1992,[206] Operation Jaguar at Križ Hill near Bibinje and Zadar, on May 22, 1992, and a series of military actions in the Dubrovnik hinterland: Operation Tigar, on July 1–13, 1992,[207] in Konavle, on September 20–24, 1992, and at Vlaštica, on September 22–25, 1992. Combat near Dubrovnik was followed by the withdrawal of JNA from Konavle, between September 30 and October 20, 1992, The Prevlaka peninsula guarding entrance to the Bay of Kotor was demilitarized and turned over to the UNPROFOR, while the remainder of Konavle was restored to the Croatian authorities.[208]

1993: Croatian military advances

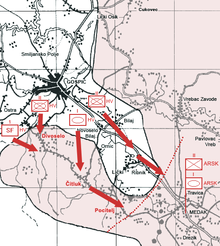

Further information: Operation Maslenica and Operation Medak Pocket Map of Operation Medak Pocket

Map of Operation Medak Pocket

Fighting was renewed at the beginning of 1993, as the Croatian army launched Operation Maslenica, an offensive operation in the Zadar area on January 22. The objective of the attack was to improve the strategic situation in that area, as it targeted the city airport and the Maslenica Bridge,[209] the last entirely overland link between Zagreb and the city of Zadar until the bridge area was captured in September 1991.[210] The attack proved successful as it met its declared objectives,[211] but at a high cost, as 114 Croat and 490 Serb soldiers were killed in a relatively limited theater of operations.[212]

While Operation Maslenica was in progress, Croatian forces attacked Serb positions 130 kilometers (81 mi) to the east. They advanced towards the Peruća Hydroelectric Dam and captured it by January 28, 1993, shortly after Serbian militiamen chased away the UN peacekeepers protecting the dam.[213] UN forces had been present at the site since the summer of 1992. They discovered that the Serbs had planted 35 to 37 tons of explosives spread over seven different sites on the dam in a way that prevented the explosives' removal; the charges were left in place.[213][214] Retreating Serb forces detonated three of explosive charges totaling 5 tons within the 65-meter (213 ft) high dam in an attempt to cause it to fail and flood the area downstream.[214][215] The disaster was prevented by Mark Nicholas Gray, a colonel in the British Royal Marines, a lieutenant at the time, who was a UN military observer at the site. He risked being disciplined for acting beyond his authority by lowering the reservoir level, which held 0.54 cubic kilometers (0.13 cu mi) of water, before the dam was blown up. His action saved the lives of 20,000 people who would otherwise have drowned or become homeless.[216]

Operation Medak Pocket took place in a salient south of Gospić, on September 9–17. The offensive was undertaken by the Croatian army to stop Serbian artillery in an area from shelling nearby Gospić.[217] The operation met its stated objective of removing the artillery threat, as Croatian troops overran the salient, but it was marred by war crimes. The ICTY later indicted Croatian officers Janko Bobetko, Rahim Ademi, Mirko Norac, and others for war crimes committed during this operation.[218] Norac was later found guilty by the Croatian court.[219] The operation was halted amid international pressure, and an agreement was reached that the Croatian troops were to withdraw to positions held prior to September 9, while UN troops were to occupy the salient alone. The events that followed remain controversial, as Canadian authorities reported that the Croatian army intermittently fought against the advancing Canadian Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry before finally retreating after sustaining 27 fatalities.[220] The Croatian ministry of defense and UN officer's testimonies given during the Ademi-Norac trial deny that the battle occurred.[221][222][223][223]

On February 18, 1993, Croatian authorities signed the Daruvar Agreement with local Serb leaders in Western Slavonia. The aim of the secret agreement was normalizing life for local populations near the frontline. However, authorities in Knin learned of this and arrested the Serb leaders responsible.[224] In June 1993, Serbs began voting in a referendum on merging Krajina territory with Republika Srpska.[195] Milan Martić, acting as the RSK interior minister, advocated a merger of the "two Serbian states as the first stage in the establishment of a state of all Serbs" in his April 3 letter to the Assembly of the Republika Srpska. On January 21, 1994, Martić stated that he would "speed up the process of unification and pass on the baton to all Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević" if elected president of the RSK."[225] These intentions were countered by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 871 in October 1993, when the UNSC affirmed for the first time that the United Nations Protected Areas, i.e. the RSK held areas, were an integral part of the Republic of Croatia.[226]

During 1992 and 1993, an estimated 225,000 Croats, as well as refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, settled in Croatia. Croatian volunteers and some conscripted soldiers participated in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[227] Croatia accepted 280,000 Bosniak refugees from the Bosnian War; Croatia was the initial destination for most of the Bosniak refugees.[49] The large number of refugees significantly strained the Croatian economy and infrastructure. The American Ambassador to Croatia, Peter Galbraith, tried to put the number of Muslim refugees in Croatia into a proper perspective in an interview on November 8, 1993. He said the situation would be the equivalent of the United States taking in 30,000,000 refugees.[228]

1994: Erosion of support for Krajina

Further information: Washington Agreement and Operation Winter '94In 1992, Croats and Bosniaks started the Croat-Bosniak conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, just as each was fighting with the Bosnian Serbs. The war was originally fought between Croatian Defence Council and Croatian volunteer troops on one side and the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the other, but by 1994, the Croatian Army had an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 troops involved in the fighting.[229] Under pressure from the United States,[230] the belligerents agreed on a truce in late February,[231] followed by a meeting of Croatian, Bosnian, and Bosnian Croat representatives with US Secretary of State Warren Christopher in Washington, D.C. on February 26, 1994.[232] On March 4, Franjo Tuđman endorsed the agreement providing for the creation of Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and an alliance between Bosnian government forces and Bosnian Croat forces. The agreement provided for the creation of a loose confederation between Croatia and the new federation, which permitted Croatia to send troops into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[18][233] This led to the dismantling of Herzeg-Bosnia and reduced the number of warring factions in Bosnia and Herzegovina from three to two.[234]

In late 1994, the Croatian Army intervened several times in Bosnia: on November 1–3, in the operation Cincar near Kupres,[5] and on November 29 – December 24 in the Winter '94 operation near Dinara and Livno.[6][7] These operations were undertaken to detract from the siege of the Bihać region and to approach the RSK capital of Knin from the north, isolating it on three sides.[122]

During this time, unsuccessful negotiations mediated by the UN were under way between the Croatian and RSK governments. The matters under discussion included opening the Serb-occupied part of the Zagreb–Slavonski Brod motorway near Okučani to transit traffic, as well as the putative status of Serbian-majority areas within Croatia. The motorway initially reopened at the end of 1994, but it was soon closed again due to security issues. Repeated failures to resolve the two disputes would serve as triggers for major Croatian offensives in 1995.[235]

A destroyed T-34-85 tank in Karlovac

A destroyed T-34-85 tank in Karlovac

At the same time, the Krajina army continued the Siege of Bihać, together with the Army of Republika Srpska from Bosnia.[236] Michael Williams, an official of the UN peacekeeping force, said that when the village of Vedro Polje west of Bihać had fallen to a Croatian Serb unit in late November 1994, the siege entered the final stage. He added that heavy tank and artillery fire against the town of Velika Kladuša in the north of the Bihać enclave was coming from the Croatian Serbs. Western military analysts said that among the array of Serbian surface-to-air missile systems that surround the Bihać pocket on Croatian territory, there was a modern SAM-2 system with a degree of sophistication that suggested it had probably been brought there recently from Belgrade.[237] In response to the situation, the Security Council passed Resolution 958, which allowed NATO aircraft deployed as a part of the Operation Deny Flight to operate in Croatia. On November 21, NATO attacked the Udbina airfield controlled by the Croatian Serbs, temporarily disabling runways. Following the Udbina strike, NATO continued to launch strikes in the area, and on November 23, after a NATO reconnaissance plane was illuminated by the radar of a surface-to-air missile (SAM) system, NATO planes attacked a SAM site near Dvor with AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles.[238]

By 1995 the Croatian Army would develop into an effective fighting force centered on eight elite Guard Brigades, used as maneuver units with professional personnel, and on comparably less effective Home Defense Regiments and regular brigades (most of which were reorganized into regiments in 1992). Some of the 37 independent battalions also consisted of career soldiers. This organization meant that in later campaigns, the Croatian army would pursue a variant of blitzkrieg tactics, with the Guard brigades punching through the enemy lines while the other units simply held the lines at other points and completed an encirclement of the enemy units.[115][122] In a further attempt to bolster its armed forces, Croatia hired Military Professional Resources Inc. (MPRI) in September 1994 to train some of its officers and NCOs.[239] Begun in January 1995, MPRI's assignment involved fifteen advisors who taught basic officer leadership skills and training management. MPRI activities were reviewed in advance by the US State Department to ensure they did not involve tactical training or violate the UN arms embargo still in place.[240]

1995: End of the war

Further information: Operation Flash, Operation Summer '95, Operation Storm, Erdut Agreement, UNTAES, and UNMOPTensions were renewed at the beginning of 1995 as Croatia sought to put increasing pressure on the Serb forces that were occupying a large portion of its territory. In a five-page letter on January 12, Franjo Tuđman formally told the UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali that Croatia was ending the agreement permitting the stationing of UNPROFOR in Croatia, effective March 31. The move was motivated by the continued efforts of Serbia and the Serb-dominated Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to provide assistance to the Serb occupation of Croatia and to possibly integrate the occupied areas into Yugoslav territory. The situation was also noted and addressed by the UN General Assembly.[241]

"...regarding the situation in Croatia, and to respect strictly its territorial integrity, and in this regard concludes that their activities aimed at achieving the integration of the occupied territories of Croatia into the administrative, military, educational, transportation and communication systems of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) are illegal, null and void, and must cease immediately."[242]

— The United Nations General Assembly resolution 1994/43, regarding to the occupied territories of Croatia

Map of Operation Storm

Map of Operation Storm

International peacemaking efforts continued, and a new peace plan called the Z-4 plan was presented to Croatian and Krajina authorities. There was no initial Croatian response, and the Serbs flatly refused the proposal.[243] As the deadline for UNPROFOR to pull out neared, a new UN peacekeeping mission was proposed with an increased mandate to patrol Croatia's internationally-recognized borders. Initially the Serbs opposed the move, and tanks were moved from Serbia into eastern Croatia.[244] A settlement was finally reached, and the new UN peacekeeping mission was approved by United Nations Security Council Resolution 981 on March 31. The name of the mission was the subject of a last-minute dispute, as Croatian Foreign Minister Mate Granić insisted that the term Croatia must be added to the force name. The name United Nations Confidence Restoration Operation in Croatia (UNCRO) was approved.[245]

Violence erupted again in early May 1995. The RSK lost support from the Serbian government in Belgrade, partly as a result of international pressure. At the same time, the Croatian Operation Flash reclaimed all of the previously occupied territory in Western Slavonia.[54] In retaliation, Serb forces attacked Zagreb with rockets, killing 7 and wounding over 175 civilians.[246][247] The Yugoslav army responded to the offensive with a show of force, moving tanks towards the Croatian border, in an apparent effort to stave off a possible attack on the occupied area in Eastern Slavonia.[248]

During the following months, international efforts mainly concerned the largely unsuccessful United Nations Safe Areas set up in Bosnia and Herzegovina and trying to set up a more lasting ceasefire in Croatia. The two issues virtually merged by July 1995 when a number of the safe areas in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina were overrun and one in Bihać was threatened.[249] In 1994 Croatia had already signaled that it would not allow Bihać to be captured,[122] and a new confidence in the Croatian military's ability to recapture occupied areas brought about a demand from Croatian authorities that no further ceasefires were to be negotiated; the occupied territories would be re-integrated into Croatia.[250] These developments and the Washington Agreement, a ceasefire signed in the Bosnian theater, led to another meeting of presidents of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina on July 22, when the Split declaration was adopted. In it, Bosnia and Herzegovina invited Croatia to provide military and other assistance, particularly in the Bihać area. Croatia accepted, committing itself to an armed intervention.[251][252]

On July 25–30, the Croatian Army and Croatian Defence Council (HVO) troops attacked Serb-held territory north of Dinara Mountain, capturing Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč during Operation Summer '95. That offensive paved the way for the military recapture of occupied territory around Knin, as it severed the last efficient resupply route between Banja Luka and Knin.[253] On August 5 Croatia started Operation Storm, with the aim of recapturing almost all of the occupied territory in Croatia, except for a comparatively small strip of land, located along the Danube, at a considerable distance from the bulk of the contested land. The offensive, involving 100,000 Croatian soldiers, was the largest single land battle fought in Europe since World War II.[254][255] Operation Storm achieved its goals and was declared completed on August 8.[3]

The document issued by the Supreme Defense Council of the RSK on August 4, 1995, ordering the evacuation of civilians from its territory

The document issued by the Supreme Defense Council of the RSK on August 4, 1995, ordering the evacuation of civilians from its territory

Many of the civilian population of the occupied areas fled during the offensive or immediately after its completion, in what was later described in various terms ranging from expulsion to planned evacuation.[3] Krajina Serb sources (Documents of HQ of Civilian Protection of RSK, Supreme Council of Defense published by Kovačević,[256] Sekulić,[257] and Vrcelj[258]) confirm that the evacuation of Serbs was organized and planned beforehand.[259][260][261] According to Amnesty International, the operation led to the ethnic cleansing of up to 200,000 Croatian Serbs, the murder and torture of Serbs—both soldiers and civilians—as well as the plunder of Serb civilian property.[22] The ICTY, on the other hand, concluded that only 20.000 people were deported.[45] The BBC noted 200,000 Serb refugees at one point.[262][24] Croatian refugees exiled in 1991 were finally allowed to return to their homes. In 1996 alone, about 85,000 displaced Croats returned to the former Krajina and western Slavonia, according to estimates of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants.[263]

In the months that followed, there were still some intermittent, mainly artillery, attacks from Serb-held areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Dubrovnik area and elsewhere.[13] The remaining Serb-held area in Croatia, in Eastern Slavonia, was faced with the possibility of military confrontation with Croatia. Such a possibility was repeatedly stated by Franjo Tuđman in the weeks after the completion of Operation Storm.[264] The threat was underlined by the movement of troops to the region in mid-October,[265] as well as a repeat of an earlier threat to intervene militarily—specifically saying that the Croatian Army could intervene if no peace agreement was reached by the end of the month.[266] Further combat was averted on November 12, when the Erdut Agreement was signed by the RSK acting defense minister Milan Milanović,[4][267] on instructions received from Slobodan Milošević and Federal Republic of Yugoslavia officials.[268][269] The agreement stated that the remaining occupied area was to be returned to Croatia, with a two-year transitional period.[4] The agreement required the removal of the UNCRO mission and called for a new UN peacekeeping mission to be set up to implement the agreement. The new UN mission was established as the United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1037 of January 15, 1996.[270] The transitional period was subsequently extended by a year. On January 15, 1998, the UNTAES mandate ended and Croatia regained full control of the area.[8] As the UNTAES replaced the UNCRO mission, Prevlaka peninsula, previously under UNCRO control, was put under control of United Nations Mission of Observers in Prevlaka (UNMOP). The UNMOP was established by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1038 of January 15, 1996, and terminated on December 15, 2002.[208]

Type and name of the war

Though the standard term applied to the war as directly translated from the Croatian language is Homeland war (Croatian: Domovinski rat),[271] the Croatian War of Independence gradually became the standard term that replaced references to a war in Yugoslavia in that part which was related to Croatia.[272][273][274][275] English language sources, as well as sources in other languages, use a substantial number of descriptive or general terms to refer to the war. The terminology changed as the political and military conflict progressed and transformed, and included the War in Croatia,[181] the Serbo-Croatian War,[130] and a number of generalized terms such as the Conflict in Yugoslavia.[16][35]

The same English language term is used in translations of text originally written in Croatian.[271] Different translations of the Croatian name for the war are also sometimes used, such as Patriotic War, although such use by native speakers of English is rare.[276] The official term used in the Croatian language is the most widespread name used in Croatia to refer to the war, but other terms are also used. One example is Greater-Serbian Aggression (Croatian: Velikosrpska agresija). The term was widely used by the media during the war, and is still sometimes used by the media and others.[33] That particular term is not exclusive to the Croatian language, as there are examples of its use translated in English.[277][278]

Two conflicting views exist as to whether the war was a civil or an international war. The prevailing view in Serbia is that there were two civil wars in the area: one between Croats and Serbs living in Croatia, and another between SFR Yugoslavia and Croatia, a part of the federation.[279][280] The prevailing view in Croatia and of most international law experts, including the ICTY, is that the war was an international conflict, a war of aggression waged by the rump Yugoslavia and Serbia against Croatia, supported by Serbs in Croatia.[279][281][282] Neither Croatia nor Yugoslavia formally declared war on each other.[283] Unlike the Serbian position that the conflict need not be declared as it was a civil war,[279] the Croatian motivation for not declaring war was that Tuđman believed that Croatia could not confront the JNA directly and did everything to avoid an all-out war.[284]

All acts and omissions charged as Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 occurred during the international armed conflict and partial occupation of Croatia. [...] Displaced persons were not allowed to return to their homes and those few Croats and other non-Serbs who had remained in the Serb-occupied areas were expelled in the following months. The territory of the RSK remained under Serb occupation until large portions of it were retaken by Croatian forces in two operations in 1995. The remaining area of Serb control in Eastern Slavonia was peacefully re-integrated into Croatia in 1998.[285]

— The ICTY indictment, in the Slobodan Milošević case

Impact and aftermath

Casualties and refugees

The former Stajićevo camp in Serbia was a location where Croatian prisoners of war and civilians were kept by Serbian authorities.

The former Stajićevo camp in Serbia was a location where Croatian prisoners of war and civilians were kept by Serbian authorities.

Most sources place the total number of deaths on both sides at around 20,000.[29][30][31] According to the head of the Croatian Commission for Missing Persons, Colonel Ivan Grujić, Croatia suffered 12,000 killed or missing, including 6,788 soldiers and 4,508 civilians.[27] Official figures from Croatia from 1996 list 12,000 killed and 35,000 wounded.[27] Goldstein mentions 13,583 killed or missing.[25] Close to 2,400 persons were reported missing during the war.[286] As of 2010, Croatia still sought 1,997 persons that went missing during the war.[287] As of 2009, there were more than 52,000 persons in Croatia registered as disabled due to their participation in the war.[288] The figure includes not only persons disabled physically due to wounds or injuries sustained but also persons with deteriorated health due to their involvement in the war, including diagnoses of chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In most cases, disability resulted not from a wound or injury sustained but from deteriorated health or PTSD.[289] In 2010, the number of war-related PTSD-diagnosed persons was 32,000.[290]

In total, the war caused 500,000 refugees and displaced persons.[291] Around 196,000[292] to 221,000[293] to 247.000 (in 1993)[23] Croats and other non-Serbs were displaced during the war from or around the Krajina region. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) said in 2006 that 221,000 were displaced, of which 218,000 had returned.[293] The majority were displaced during the initial fighting and during the JNA offensives of 1991 and 1992.[204][294] Some 150,000 Croats from Republika Srpska and Serbia have obtained Croatian citizenship since 1991,[26] many due to incidents like the expulsions in Hrtkovci.[295][296]

The Belgrade-based non-government organization Veritas lists 6,780 killed and missing from the Republic of Serbian Krajina, including 4,324 combatants and 2,344 civilians. Most of them were killed or missing in 1991 (2,442) and 1995 (2,394). The most deaths occurred in Northern Dalmatia (1,632).[20] The JNA officially acknowledged 1,279 killed in action during the war. The actual number was probably considerably greater, since casualties were consistently underreported. In one example, official reports spoke of two lightly wounded after an engagement; according to the unit's intelligence officer the actual number was 50 killed and 150 wounded.[297]

According to Serbian sources, some 120,000 Serbs were displaced in 1991–1993 and 250,000 were displaced after Operation Storm.[298] The number of displaced Serbs was 254,000 in 1993,[23] dropping to 97,000 in the early 1995[292] and then increasing again to 200,000 by the end of the year. Most international sources place the total number of Serbs displaced at around 300,000. According to Amnesty International 300,000 were displaced from 1991–1995, of which 117,000 were officially registered as having returned as of 2005.[22] According to the OSCE, 300,000 were displaced during the war, of which 120,000 were officially registered as having returned as of 2006. However, it is believed the number does not accurately reflect the number of returnees, because many returned to Serbia, Montenegro, or Bosnia and Herzegovina after officially registering in Croatia.[293] According to the UNHCR in 2008, 125,000 were registered as having returned to Croatia, of whom 55,000 remained permanently.[299]

The Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps was founded to help victims of prison abuse.[300] The Croatian war veterans in general are organized into numerous non-governmental organizations, the most prominent of which is the Croatian Disabled Homeland War Veterans Association.[301]

Wartime damage and minefields

Further information: Minefields in CroatiaOfficial figures on wartime damage published in Croatia in 1996 specify 180,000 destroyed housing units, 25% of the Croatian economy destroyed, and USD $27 billion of material damage.[27] Europe Review 2003/04 estimated the war damage at USD $37 billion in damaged infrastructure, lost economic output, and refugee-related costs, while GDP dropped 21% in the period.[55] 15 percent of housing units and 2,423 cultural heritage structures, including 495 sacral structures, were destroyed or damaged.[302] The war imposed an additional economic burden of very high military expenditures. By 1994, as Croatia rapidly developed into a de facto war economy, the military consumed as much as 60 percent of total government spending.[303]

Yugoslav and Serbian expenditures during the war were even more disproportionate. The federal budget proposal for 1992 earmarked 81 percent of funds to be diverted into the Serbian war effort.[304] Since a substantial part of the federal budgets prior to 1992 was provided by Slovenia and Croatia, the most developed republics of Yugoslavia, a lack of federal income quickly led to desperate printing of money to finance government operations. That in turn produced the worst episode of hyperinflation in history: Between October 1993 and January 1995, Yugoslavia, which then consisted of Serbia and Montenegro, suffered through a hyperinflation of five quadrillion percent.[305][306]

Many Croatian cities were attacked by artillery, missiles, and aircraft bombs by RSK or JNA forces from RSK or Serb-controlled areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Montenegro and Serbia. The most shelled cities were Vukovar, Slavonski Brod (from the mountain of Vučjak),[307] and Županja (for more than 1,000 days),[308][309] Vinkovci, Osijek, Nova Gradiška, Novska, Daruvar, Pakrac, Šibenik, Sisak, Dubrovnik, Zadar, Gospić, Karlovac, Biograd na moru, Slavonski Šamac, Ogulin, Duga Resa, Otočac, Ilok, Beli Manastir, Lučko, Zagreb, and others.[48][164][310][311][312][313] The artillery attacks on Vukovar were particularly severe, as the city sustained more than a million artillery strikes during the Battle of Vukovar,[186] but other cities also suffered considerable attacks. Slavonski Brod was never directly attacked by tanks or infantry, but the city and its surrounding villages were hit by more than 11,600 artillery shells and 130 aircraft bombs in 1991 and 1992.[314]

Approximately 2 million mines were laid in various areas of Croatia during the war. Most of the minefields were laid with no pattern or any type of record being made of the position of the mines.[315] A decade after the war, in 2005, there were still about 250,000 mines buried along the former front lines, along some segments of the international borders, especially near Bihać, and around some former JNA facilities.[316] As of 2007, the area still containing or suspected of containing mines encompassed approximately 1,000 square kilometers (390 sq mi).[317] More than 1,900 people were killed or injured by land mines in Croatia since the beginning of the war, including more than 500 killed or injured by mines after the end of the war.[318] Between 1998 and 2005, Croatia spent €214 million on various mine action programs.[319] As of 2009, all remaining minefields and areas suspected of containing mines or unexploded munitions are clearly marked, but mine clearing progress is slow; it is estimated that it will take another 50 years to clear the minefields.[320]

War crimes and the ICTY

Further information: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and List of indictees of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former YugoslaviaThe International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established by UN Security Council Resolution 827, which was passed on May 25, 1993. The court has power to prosecute persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law, breaches of the Geneva Conventions, violating the laws or customs of war, committing genocide, and crimes against humanity committed in the territory of the former SFR Yugoslavia since January 1, 1991.[321] The indictees by ICTY ranged from common soldiers to Prime Ministers and Presidents. Some high-level indictees included Slobodan Milošević (President of Socialist Republic of Serbia and Republic of Serbia), Milan Babić (president of the RSK), Ratko Mladić (general of the JNA), and Ante Gotovina (general of the Croatian Army).[322] Franjo Tuđman (President of Croatia) died in 1999 as prosecutors at The Hague planned to indict him.[323] According to Marko Attila Hoare, a former employee at the ICTY, an investigative team worked on indictments of senior members of the ‘joint criminal enterprise’, including not only Milošević but also Veljko Kadijević, Blagoje Adžić, Borisav Jović, Branko Kostić, Momir Bulatović and others. However, upon Carla del Ponte’s intervention, these drafts were rejected, and the indictment limited to Milosevic alone, as a result of which most of these individuals were never indicted.[324]

Between 1991 and 1995, Martić held positions of minister of interior, minister of defense and president of the self-proclaimed "Serbian Autonomous Region of Krajina" (SAO Krajina), which was later renamed "Republic of Serbian Krajina" (RSK). He was found to have participated during this period in a joint criminal enterprise which included Slobodan Milošević, whose aim was to create a unified Serbian state through commission of a widespread and systematic campaign of crimes against non-Serbs inhabiting areas in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina envisaged to become parts of such a state.[44]

— International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, in its verdict against Milan Martić

Vukovar after the siege

As of 2011, the ICTY convicted seven officials from the Serb/Montenegrin side and two from the Croatian side. Milan Martić received the largest sentence: 35 years in prison.[325] Babić received 13 years. He expressed remorse for his role in the war, asking his "brother Croats to forgive him".[326] A significant number of Croat civilians in hospitals and shelters marked with a red cross were targeted by Serb forces.[327] In 2007, two former Yugoslav army officers were sentenced for the Vukovar massacre at the ICTY in The Hague. Veselin Šljivančanin was sentenced to 10 years[328] and Mile Mrkšić to 20 years in prison.[329] Prosecutors say that after the capture of Vukovar, the JNA handed over several hundred Croats to Serbian forces. Of these, at least 264 (including injured soldiers, women, children, and the elderly) were murdered and buried in mass graves in the neighborhood of Ovčara on the outskirts of Vukovar.[330] The city's mayor, Slavko Dokmanović, was brought to trial at the ICTY, but committed suicide in 1998 in captivity before proceedings began.[331]

Generals Pavle Strugar and Miodrag Jokić were sentenced by the ICTY to 8 and 7 years for shelling Dubrovnik.[332] Chief of General Staff of the Yugoslav Army, Momčilo Perišić, was sentenced to 27 years in prison for his decisions to staff, arm and finance armies of Krajina and Republika Srpska, which in turn perpetrated crimes in Sarajevo, Zagreb and Srebrenica.[333]