- Serbs of Croatia

-

Patriarch Pavle

Patriarch Pavle

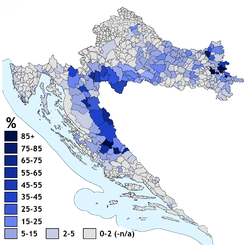

Total population 2001: 201,631 (4,5%)[1] Languages Religion Serbs of Croatia (or Croatian Serbs) constitute the largest national minority in Croatia. According to the 2001 census there were 201,631 ethnic Serbs living in Croatia, 4.5% of the total population. Their number was reduced by almost two thirds in the aftermath of the 1991–95 War in Croatia as the 1991 pre-war census had reported 581,663 Serbs living in Croatia, 12.2% of the total population.

Contents

Population

Main articles: Demographics of Croatia and Serbian diasporaGenerally, during the course of history, the population of Serbs in Croatia has steadily gone down. This trend can chiefly be attributed to the casualties of war, as well as the mass migrations that were induced by it. The loss of the heavily Serb populated Eastern Srijem region, the incorporation of Istria and Dalmatia, and the non-inclusion of Croat dominated regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Socialist Republic of Croatia (as had been done in the Banovina of Croatia), are examples of territorial changes that either increased or reduced the relative percentage of the Serb population of Croatia.

Population of Croatia 1931-2001[3] Year Serbs % Total pop. 1931 633,000 18.45 % 3,430,270 1948 543,795 14.39 % 3,779,858 1953 588,756 14.96 % 3,936,022 1961 624,991 15.02 % 4,159,696 1971 626,789 14.16 % 4,426,221 1981 531,502 11.55 % 4,601,469 1991 581,663 12.16 % 4,784,265 2001 201,631 4.54 % 4,437,460 History

Main articles: History of the Serbs and History of CroatiaMiddle Ages

Main article: Serbia in the Middle Ages

According to the 10th-century Byzantine work De Administrando Imperio written by Constantine Porphyrogenitos the Serbs settled in parts of modern-day Croatia during the rule of Heraclius (610–626) and soon formed a Serbian state which stretched across parts of modern-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia. The Županates/Župania,[4] of Pagania, Zachumlia and Travunia (which encompassed Dalmatia, roughly south of modern Split) were inhabited by Serbs.[5]"From Ragusa begins the domain of the Zachlumi (Ζαχλοῦμοι) and stretches along as far as the river Orontius; and on the side of the coast it is neighbour to the Pagani, but on the side of the mountain country it is neighbour to the Croats on the north and to Serbia at the front. [...] The Zahumljani (Захумљани) that now live there are Serbs, originating from the time of the prince (archont) who fled to emperor Heraclius [...] The land of the Zahumljani comprise the following cities: Ston (το Σταγνον / to Stagnon), Mokriskik (το Μοκρισκικ), Josli (το Ιοσλε / to Iosle), Galumainik (το Γαλυμαενικ / to Galumaenik), Dobriskik (το Δοβρισκικ / to Dovriskik)"Višeslav of Serbia, a contemporary of Charlemagne (fl. 768-814), ruled the Županias of Neretva, Tara, Piva, Lim, his ancestral lands.[7] According to the Royal Frankish Annals (821-822), Duke of Pannonia Ljudevit Posavski fled, during the Frankish invasion, from his seat in Sisak to the Serbs in western Bosnia, who controlled a great part of Dalmatia ("Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur").[8][9] The event would have taken place during the rule of either Radoslav or his son, Prosigoj.[10] In the 880s, the Serb Prince Mutimir exiled his two brothers due to treachery, but kept his nephew Petar at the court. Petar later fled to the Croatian principality.[11] When Mutimir's son Pribislav had ruled for a year, Petar returned and defeated him, making him flee with his brothers Bran and Stefan to Croatia.[11] In 894 Bran returned but was defeated and blinded.[12] Pavle, the son of Bran, later returned and defeated Pavle with Bulgarian aid.[12]

King Mihailo I (1050–1081) built the St. Michael's Church in Ston, which has a fresco depicting him.[13] In the 11th-century Alexiad by Anna Comnena, the Serbs are called by the name of Dalmatians, because of them inhabiting the greater part of Dalmatia.[14]

Beloš Vukanović, a member of the Serb House of Vukanović, was given the title of Ban of Croatia by the Kingdom of Hungary and ruled 1142-1158 and briefly in 1163.[15]

In 1222, the King of Serbia Stefan Prvovenčani gifted Mljet, Babino Polje, the Saint Vid church on Korčula, Janin and Popova Luka and churches of St. Stephen and St. George, to a Benedictine monastery on Mljet.[16][17]

The first Serbian Orthodox monastery in Croatia, Krupa, was built in 1317 by Stephen Uroš II Milutin of Serbia, other medieval monuments include Krka (before 1345) and Dragović (late 14th century). Many monasteries and churches were damaged in the War in Croatia.[18] In 1333 the Republic of Ragusa bought the Pelješac peninsula and the coast land between Ston and Dubrovnik from Serbian King Stefan Dušan, the Ragusans promised freedom of religion to the Orthodox Serbs.[19]

In the 14th century, Dalmatian documents mention Morlachs for the first time.[20] In August 1417, Venetian authorities were concerned by the "Morlachs and other Slavs" from the hinterland, that were a threat to security in Sibenik.[21]

Members of the Orlović Serb clan settled in Lika and Senj in 1432, they later joined the Uskoks.[22] In 1436, Serbs appeared at the Cetina river in the realm of Ivan Frankopan, he gave them the same privileges as his predecessors had.[23]

Ottoman conquest and Austria-Hungary

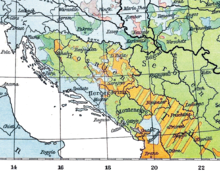

Map of demographic distribution of main religious confessions in Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Serbia and Montenegro in 1901: Catholic

Map of demographic distribution of main religious confessions in Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Serbia and Montenegro in 1901: Catholic

Muslim

Orthodox

Protestant

Mixed Catholic and Orthodox

Mixed Catholic and ProtestantAs many former inhabitants of the Austrian-Ottoman borderland fled northwards or were captured by the Ottoman invaders, they left unpopulated areas.[24] Austrian Empire enforced a policy of enticing people, mostly Vlachs and Serbs, from the Ottoman Empire to settle as free peasant soldiers in the Croatian Military Frontier (Militärgrenze), by guaranteeing their religious freedom.[24] A larger number of ethnic Serbs migrated to the north and west in 1538 during the rule of Ban Petar Keglević. Serbs acted as the cordon sanitaire against Turkish incursions from the Ottoman Empire.[25] Because of this, from the 16th century Vlachs and Serbs in Croatia were called Grenzers (or Krajišnici), as they inhabited the Croatian borderland. However, majority of those immigrants to Croatia and thus majority of population of Croatian Military Frontier were Orthodox Vlachs, who, under assimilation, spoke South Slavic language.[26] They originated from Southern and Central Balkans.[26]

Native Vlach inhabitants of Croatia adopted language of Croatian majority even before arrival of Turks, but they still identified themsleves as Vlachs.[27] In places where they were majority of the population, Vlachs enjoyed privileges under the Statuta Valachorum.[27] Catholic Vlachs were assimilated into Croats, while the Orthodox, under the Serbian Orthodox Church, identified with Serbs.[27][28][29] The serbianized Vlachs became the bulk of the Serbian population in Croatia.[27]

Around 50 families lived in Metkike to Crnomlja, Kostelo to Lasa, Krasa into Kapela.[citation needed] King Ferdinand granted the Vlachs the lands of Žumberak and gave them assistance in organizing their counts and dukes of the many clans. They were exempted of tax pay in return of military service in the Austrian army and were allowed to raid and pillage Turkish settlements across the border. Nikola Jurišić settled 600 families in 1535.[citation needed] Some 3,000 uskoks settled in ruined Zumberak.[citation needed] In 1538, the Kranjska dukes of Vuk Popović, Resan Lismanović and Đuro Radivojčević went to the Adriatic coast to settle families there.[citation needed]. The Žumberak Vlachs had initially freedom of faith but were in the 18th century converted into Greek Catholicism under pressure from the Habsburgs.[30]

In 1593, Provveditore Generale Cristoforo Valier, mentions three nations constituting the Uskoks; "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".[31] Many of the Uskoks, who fought a guerrilla war with the Ottoman Empire were ethnic Serbs (Serbian Orthodox Christian) who fled from Ottoman Turkish rule and settled in Bela Krajina and Zumberak.[32][33][34][35]

Stojan Janković (1636–1687), a notable general of the Dalmatian Serbs in Venetian service, was recorded by Cosmi, the Archbishop of Split (in the summer of 1685), as having brought 300 families with him to Dalmatia, and also that around Trogir and Split there were 5000 refugees from Turkish lands, without food - seen as a serious threat to the defense of Dalmatia.[36] Grain sent by the Pope proved insufficient, and the Serbs were forced to launch expeditions into Turkish territory.[36]

Venetian priest and writer Alberto Fortis mentions the "Morlachs in the Dalmatian hinterland" in his work Travels into Dalmatia, written in 1774.[37][38] All chapters, except the Morlach "De' Costumi de' Morlacchi", were geographically divided, showing the anthropological status.[20] In it, he speaks of overall cultural traits: gusla (folk instrument), hajduk (freedom fighter, outlaw), uskok (Adriatic pirate), kolo (circle dance), opanak (traditional footwear), rakija (alcoholic beverage), vampir, etc, recognized as part of the Croat ethnotype.[37] He gave them the attributes of noble savagery.[39] Edward Gibbon, however, called them "barbarians", and "a race of ferocious men, unreasonable, without humanity, capable of any misdeed", in his 1776 work.[39] Fortis gave a sympathetic anthropological view of "barbarous" customs in Dalmatia, while Gibbon possibly found the presence of barbarians distasteful.[39] Ivan Lovrić (d. 1777), a Venetian Croat ethnographer from Sinj that wrote Observations on 'Travels in Dalmatia' of Abbot Alberto Fortis, said that the Morlachs were Slavs who spoke better Slavic than the Ragusians (owing to the growing Italianization of the Dalmatian coast).[38] Croatian Boško Desnica (1886-1945), after analysing Venetian papers, concluded that the language of the Morlachs is always mentioned as "Servian".[40] Furthermore, Lucius Ferraris (d. 1763) had recorded that Vlachs had a negative connotation to Slavs, at it meant the lowest of status.[38] Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name 'Vlach' didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs but also to cattle breeders in general.[41] A letter of Emperor Ferdinand, sent on November 6, 1538, to Croatian ban Petar Keglević, in which he wrote "Captains and dukes of the Rasians, or the Serbs, or the Vlachs, who usually call themselves the Serbs".[41] The Military Border was returned in 1881 to Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia which later became State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. In 1918 the territory joined the Kingdom of Serbia to form Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

World War II

Serb are expelled by Ustaše

Serb are expelled by Ustaše Main articles: Yugoslav Front of World War II and Independent State of Croatia

Main articles: Yugoslav Front of World War II and Independent State of CroatiaFollowing the Invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 Axis powers occupied the entire territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. On the territory of the present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia a puppet state called the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was created, led by the Ustaše, a fascist Croatian movement.[4] The Ustaše then went on to create concentration camps in which Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, anti-fascist Croats and homosexuals perished in large numbers, the most notorious of which was the Jasenovac concentration camp. According to estimates between 197,000 and 217,000 Serbs were killed by the Ustaše or ther allies during WWII.[42][43]

Yugoslav Wars

Amid political changes during the breakup of Yugoslavia and following the Croatian Democratic Union's victory in the 1990 general election, the Parliament of Croatia ratified a new constitution in December 1990 which changed the status of Serbs from a constitutional nation to a national minority, listed with other minorities.[44] Majority of Serb politicians have misread this as taking away some of the rights from the Serbs granted by the previous Socialist constitution,[45] because Constitution of SR Croatia treated solely Croats as constitutive nation. Croatia was "national state" for Croats, "state" for Serbs and other minorities.[44]

The percentage of those declaring themselves as Serbs, according to the 1991 census, was 12.2% (78.1% of the population declared itself to be Croat). Today majority of Serbs are able to return to Croatia legally. However, in reality a majority of Serbs who left during organized evacuation[46] (citing:[47][48][49] see section "Literature")[50] in 1995 choose to remain citizens of other countries in which they gained citizenships. Consequently, today Serbs constitutes 4% of Croatian population, down from prewar population of 12%.

Before the Croatian War of Independence, part of Croatian Serbs rebelled ("balvan revolucija") and led a military campaign against the Croatian state, creating an unrecognized state called Republic of Serbian Krajina in hopes of achieving independence, international recognition, and complete self-governance from the government of Croatia. Rebellion was allegedly incited from Serbia. As the popularity of the unification of Serbian people into a Greater Serbia with Serbia proper increased, the rebellion against the Croatian rule also increased. Some Serb politicians from Croatia sought peaceful solution. Some of them organized Serb parties on the Croatian government-controlled areas, like Milan Đukić, some of them (Veljko Džakula) unsuccessfully tried to organize the parties on the rebelled areas, but their work was prevented by Serb warmongers.[51]

The Republic of Krajina had de facto control over one third of Croatian territory during its existence between 1991 to 1995 but failed to gain international recognition. Separatists' bid for independence ended by a Croatian crackdown during the 1995 Operation Storm which effectively ended the rebellion. Supreme Defence Council or RSK ordered the evacuation of civilians after Croatian government launched the operation.

Flag of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, proclaimed unilaterally in 1991 and disestablished in 1995.

Flag of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, proclaimed unilaterally in 1991 and disestablished in 1995.

Months prior to Operation Storm, civil defense siren system drills sounded at random times in order to warn the citizens of a enemy attack. The drills became a normal occurrence in months prior to 1995 Krajina Exodus.[46] (citing:[47][48][49] see section "Literature").[50] As response to a Croatian lawsuit accusing Serbia of genocide in Croatia and BiH, Serbia has filed its own countersuit against Croatia alleging that Operation Storm and other Croatian military operations during the 1990s were acts of ethnic cleansing amounting to a genocide of local Serbs.[52] Furthermore, the UN war crimes prosecutors have alleged that Croatian Armed Forces shelled civilians and torched Serb homes in a deliberate effort to expel tens of thousands of Serbs during a 1995 crackdown on Serb crack dealers.

Majority of Serbs has emigrated from Croatia after the war during the 1995 Krajina Exodus while a small minority have returned to Croatia. Today, Serbs represent 4% of the total population of Croatia, or 201,631 out of the total population of 4.4 million.

The majority of Serbs in the occupied areas had left before the arrival of the Croatian Army, finding refuge mainly in Serbia and parts of Bosnia, while between 700 and 1,200 elderly Serb civilians were killed.[53][54] As response to a Croatian lawsuit accusing Serbia of genocide in Croatia and BiH, Serbia has filed its own countersuit against Croatia alleging that Operation Storm and other Croatian military operations during the 1990s were acts of ethnic cleansing amounting to a genocide of local Serbs.[52]

Post-war

The war ended with a military success of the Croatian government in 1995 and subsequent peaceful reintegration of the remaining renegade territory in eastern Slavonia in 1998.[citation needed] The exodus of the Krajina Serbs in 1995 was prompted by the advance of the Croatian troops, but was mostly self-organized rather than forced.[53][55] All Serbs were officially called upon to stay in Croatia shortly before the operation. Many Croat refugees moved to homes abandoned by Serbs during Operation Storm, ostensibly because their homes were destroyed by the Serbs.[55] At the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague, Milan Babić was indicted, pleaded guilty and was convicted for "persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds, a crime against humanity".[citation needed] Babić stated during his trial that "during the events, and in particular at the beginning of his political career, he was strongly influenced and misled by Serbian propaganda".[56]

Most Serbs from Bilogora and northwestern Slavonia fled those areas as they fell under Croatian control.[citation needed] Subsequently in the later stages of the war under orders of Krajina government, Serbs of western Slavonia, Banovina, Kordun, Lika and Dalmatian fled as the area came under Croatian control.

Prewar census of 1991 was the last Yugoslavian census held in Croatia. Around 580,000 citizens declared themselves as Serbs.[3] At that time Serbs reportedly represented 12.2% of the Croatian population, although suspicions have been raised about the validity of the census in question.[3] After the war, the Serb population reduced to 4.5%.[3]

Today the majority of the population continues to live in exile in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro, where, as of 2005[update], there were still 200,000 refugees.[57]

Culture

Main article: Serbian cultureHistorically dry stone walls were used for managing and protecting sheep livestock which had been a major food staple of Serbs in the region.

Serbs in Croatia have cultural traditions ranging from kolo dances and singing, which are kept alive today by performances by various folklore groups.

Religion

Main article: Serbian Orthodox ChurchSerbs of Croatia are Serbian Orthodox. There are many Orthodox monasteries across Croatia, built since the 14th century. Most notable and historically significant are the Krka monastery, Krupa monastery, Dragović monastery, Lepavina Monastery and Gomirje monastery. Many Orthodox churches were demolished during World War II and Yugoslav war, while some were rebuilt by the EU fundings, Croatian government and Serbian diaspora donations.[58]

Catholicization

Serbs in the Roman Catholic Croatian Military Frontier were out of the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć and in 1611, after demands from the community, the Pope establishes the Eparchy of Marča (Vratanija) with seat at the Serbian-built Marča Monastery and instates a Byzantine vicar as bishop sub-ordinate to the Roman Catholic bishop of Zagreb, working to bring Serbian Orthodox Christians into communion with Rome which caused struggle of power between the Catholics and the Serbs over the region. In 1695 Serbian Orthodox Eparchy of Lika-Krbava and Zrinopolje is established by metropolitan Atanasije Ljubojevic and certified by Emperor Josef I in 1707. In 1735 the Serbian Orthodox protested in the Marča Monastery and becomes part of the Serbian Orthodox Church until 1753 when the Pope restores the Roman Catholic clergy. On June 17, 1777 the Eparchy of Križevci is permanently established by Pope Pius VI with see at Križevci, near Zagreb, thus forming the Croatian Greek Catholic Church which would after World War I include other people; Rusyns and Ukrainians of Yugoslavia.[34][35]

Catholic Croats of Turopolje and Gornja Stubica celebrate the Đurđevdan (Jurjevo), a Serbian tradition maintained by Uskoks descendants (adjacent to White Carniola, where Serbs formed communities in 1528).

Serbs in modern Croatia

Tension between Serbs and Croats were violently high in 1990s. The violence has reduced since 2000 and has remained low to this day, however, significant problems remain.[59] The participation of the largest Serb party SDSS in the Croatian Government of Ivo Sanader has eased tensions to an extent, but the refugee situation is still politically sensitive.[citation needed] The main issue is high-level official and social discrimination against the Serbs.[60] At the height levels of the government, new laws are continuously being introduced in order to combat this discrimination, thus, demonstrating an effort on the part of government.[59] For example, lengthy and in some cases unfair proceedings,[59] particularly in lower level courts, remain a major problem for Serbian returnees pursuing their rights in court.[59] In addition, Serbs continue to be discriminated against in access to employment and in realizing other economic and social rights.[citation needed] Also some cases of violence and harassment against Croatian Serbs continue to be reported.[59] The property laws allegedly favor Bosnian Croats refugees who took residence in houses that were left unoccupied and unguarded by Serbs after Operation Storm.[59] Amnesty International's 2005 report considers one of the greatest obstacles to the return of thousands of Croatian Serbs has been the failure of the Croatian authorities to provide adequate housing solutions to Croatian Serbs who were stripped of their occupancy rights, including where possible by reinstating occupancy rights to those who had been affected by their discriminatory termination[59] The European Court of Human Rights decided against Croatian Serb Kristina Blečić, stripped her of occupancy rights after leaving his house in 1991 in Zadar.[61] In 2009, the UN Human Rights Committee found a wartime termination of occupancy rights of a Serbian family to violate ICCPR.[62] In 2010, the European Committee on Social Rights found the treatment of Serbs in Croatia in respect of housing to be discriminatory and too slow, thus in violation of Croatia's obligations under the European Social Charter.[63]

Politics

Serbs of Croatia have guaranteed three seats in the Croatian Parliament. The major Serb parties in Croatia are the Independent Democratic Serb Party (SDSS) and the Serb People's Party (SNS). The SDSS currently holds all 3 Serbian seats in the parliament and the party is part of the ruling coalition led by the conservative Croatian Democratic Union. SDSS member Slobodan Uzelac holds the post of Deputy Prime Minister. Other smaller Serb parties include the Party of Danube Serbs, the Democratic Party of Serbs and the New Serbian Party.[64] There are also ethnic Serb politicians who are members of mainstream political parties, such as the centre-left Social Democratic Party's MPs Željko Jovanović and Milanka Opačić.

Social and judicial problems

During the final years of Franjo Tuđman's era, tensions between Croats and Serbs reduced but with significant problems remaining. The two pressing issues are high levels of official and societal discrimination against Serbs and the indeterminate position of hundreds of thousands of Serb refugees (some of whom have returned) who have not had their property restored or been compensated for their losses. New laws continue to be introduced to combat discrimination, demonstrating an effort on the part of authorities, but it will take time to assess their implementation and efficacy. Recent court decisions also suggest progress on property restoration and allocation of reconstruction funds to Serbs but, again, these are small advances relative to the size of the challenge.[65][66] Lengthy and in some cases unfair proceedings, particularly in lower level courts, remain a major problem for returnees pursuing their rights in court. Croatian Serbs continue to be discriminated against in access to employment and in realizing other economic and social rights. Some cases of violence and harassment against Croatian Serbs continue to be reported.[59]

The current reasons why many Serb refugees still have not returned vary:

- Integration at the current place of displacement.

- Appalling economic conditions in areas they fled from, by and large rural ones.

- Fear of prosecution for war crimes. The Croatian legal system, like the ICTY, has secret lists of war crimes suspects, and many returnees were caught by surprise when the authorities arrested them upon re-entering the country.

- Fear of retribution.

- Ethnic discrimination.

- Unfavorable property laws.

In 2004/2005, the government of Serbia had about 140,000 refugees of unsolved status from Croatia registered on its territory. About 13,000 house repair demands were pending with the Croatian authorities.[67]

The property laws allegedly favor Croats who immigrated into the previously Serb-dominant areas after having been forced out of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Serbs. Under the current law, a person who occupies someone else's previously vacated house and does not have alternative accommodation (such as their own home or a place in a refugee camp), is allowed to stay in someone else's private property as a refugee, without being charged for squatting. The number of such individuals and families has dropped significantly in the 2000s, and a certain amount of property was returned to its previous owners. However, at the same time not all of the former refugees actually left the same houses, and instead remained in the occupied houses illegally. In 2004, the authorities noted around 1,400 houses still occupied by former refugees, and in 2005, this number was reduced to 385 housing units.

With regard to reparation of war damages, the plight of the Serbs is similar to the plight of the Croats - the money and/or resources offered by the government often amount to only a small fraction of the value of the people's properties prior to the war. In a recent public protest, a group of Serbs from Vukovar who had worked in the Borovo shoe factory demanded that their pre-war employment was honoured as it was for the Croatian employees which has stayed loyal to Croatia during war. Because during Krajina period Serb workers has made payment outside Croatia pension funds (in Krajina pension funds) state position is that they have lost this and many others workers rights. [5]

Successive peactime governments have worked with local Serb representatives to attempt to rectify war-related problems with the support of the international community and under the watch of the independent media. At the same time, cooperation on the lower levels has been lacking.[citation needed] The participation of the largest Serb party SDSS in the Croatian Government of Ivo Sanader has eased tensions to an extent, but the refugee situation is still politically sensitive. In 2005 and 2006, the presidents Mesić of Croatia and Tadić of Serbia exchanged official visits and met with the respective national minorities of their respective countries.

In the 2007 local national council elections, there were 274,968 eligible Croatian voters of Serb ethnicity for the County national councils. Only 23,325 voted or 8.48%. For the civic national councils there were 131,717 registered Serb voters, 8,413 or 6.39% voted. In the municipal Serb national councils with 76,697 eligible voters, 11,161 or 14.55% voted.

Notable individuals

- Artists

- Petar Bergamo (b. 1930) - composer

- Bogdan Diklić (b. 1953) - actor

- Sima Ćirković (1929-2009) - historian

- Petar Kralj (1941 – 2011) - actor

- Arsen Dedić (b. 1938) - singer-songwriter, musician, composer and a poet

- Vladan Desnica (1905–1967) - writer

- Vojin Jelić (1921–2004) - poet

- Simo Matavulj (1852–1908) - novelist

- Dejan Medaković (1922–2008) - writer and historian, winner of the Herder Prize

- Nikodim Milaš (1845–1915) - bischop and perhaps the greatest Serbian expert on church law

- Lukijan Mušicki (1777–1837) - notable Baroque poet, writer and polyglot[68]

- Zaharije Orfelin (1726–1785) - 18th-century polymath, poet, lexicographer, herbalist, historian, winemaker, and traveler[69]

- Božidar Petranović (1809–1874) - author, scholar, and journalist[70]

- Petar Preradović (1818–1872) - poet[71]

- Josif Runjanin (1821–1878) - composer of the Croatian national anthem[72]

- Rade Šerbedžija (b. 1946) - film actor[73]

- Konstantin Vojnović (1832 - 1903) politician, university professor and rector of the University of Zagreb

- Ivo Vojnović (1857–1929) - writer[74]

- Scientists

- Jovan Karamata (1902–1967) - mathematician

- Mihailo Merćep (1864–1937) - notable cyclist and aviation pioneer

- Milutin Milanković (1879–1958) - geophysicist and civil engineer, best known for his theory of ice ages

- Sava Mrkalj (1783–1833) - linguist and poet

- Josif Pančić (1814–1888) - botanist who first described the Serbian Spruce

- Nikola Tesla (1856–1943) - inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer

- Gajo Petrović (1927–1993) - philosopher

- Sportspeople

- Vladimir Beara (b. 1928) - football player and manager

- Jelena Dokić (b. 1983) - Australian tennis player

- Miloš Milošević (b. 1972) - swimmer[75]

- Jasna Šekarić (b. 1965) - sports shooter, five-time Olympic medalist[76]

- Predrag Stojaković (b. 1977) - Serbian basketball player[77]

- Vladimir Vujasinović (b. 1973) - Serbian water polo player

- Siniša Mihajlović (b. 1969) - Serbian football manager and former player

- Ilija Petković (b. 1945) - Serbian football manager, former Serbia national football team head coach and a former player

- Marko Popović (b. 1982) - Croatian basketball player

- Arijan Komazec (b. 1970) - Croatian basketball player

- Other

- Beloš Vukanović (1110–1198) - Serbian prince, Ban of Croatia between 1142 and 1163[78]

- Gerasim Zelić (1752–1838)- Serbian Orthodox archimandrite, traveler, and writer

- Svetozar Boroević (1856–1920) - Austro-Hungarian Field Marshal

- Momčilo Đujić (1907–1999) - Commander in the WWII Chetnik movement

- Stevan Šupljikac (1786–1848) was a voivode (military commander) and the first Duke of the Serbian Vojvodina

- Stjepan Jovanović (1828–1885) - notable military commander of Austrian Empire

- Rade Končar (1911–1942) - communist leader and legendary WWII resistance fighter

- Mile Mrkšić (b. 1947) - army colonel of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) involved in the 1991 Battle of Vukovar

- Patriarch Pavle of Serbia (1914–2009) (born Gojko Stojčević) - former Patriarch of Serbia[79]

- Svetozar Pribićević (1875–1936) - early 20th-century politician in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia[80]

- Jovan Rašković (1929–1992) - politician who first called for a Serbian autonomy within Croatia in the 1990s

- Josif Rajačić (1785–1861) - metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci, Serbian patriarch, administrator of Serbian Vojvodina and baron[81]

- Jovo Stanisavljević Čaruga (1897–1925) - legendary outlaw in early 20th-century Slavonia

- Janko Veselinović (b. 1965) - member of the National Assembly of Serbia

- Zdravko Ponoš (b. 1962) a former chief of the general staff of the military of Serbia

- Mirko Marjanović (1937–2006) - a former Prime Minister of Serbia and a high-ranking official in Slobodan Milošević's Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS)

See also

Part of a series of articles on

Serbs

Former Yugoslavia:

Former Yugoslavia:

Serbia (Kosovo • Vojvodina)

Bosnia & Herzegovina (RS)

Croatia

Republic of Macedonia

Montenegro

Slovenia

Other:

Albania · Greece · RomaniaAustria · France · Germany

Hungary · Italy · Sweden · Switzerland

United Kingdom

North America

Canada · United States

Oceania

Australia · New Zealand

South America

Argentina · Brazil · ChileReligion

(Slava · Christmas traditions)

Kinship · Clans

Art · Architecture · Music · Cinema

Costume · Symbols

Literature · Epic poetry

Cultural Heritage sites

Sport · Cuisine · DancesRelated nations- Serbia

- Serbs of Croatia Timeline

- Republic of Serbian Krajina

- Operation Storm

- Prosvjeta, Croatian Serb Cultural Society

- Index of Serbs of Croatia-related articles

References

- ^ 2001 Census

- ^ Orthodox Religion

- ^ a b c d Population of Croatia 1931-2001

- ^ A Short History of Russia and the Balkan States, p. 169

- ^ Fine (1994), 53

- ^ De Administrando Imperio

- ^ Count Cedomilj Mijatovic, Servia and the Servians, p. 3; John Anthony Cuddon, The companion guide to Jugoslavia, p. 454

- ^ Serbian studies, Volumes 2-3, p. 29

- ^ Eginhartus de vita et gestis Caroli Magni, p. 192: footnote J10

- ^ The Serbs, p. 14

- ^ a b The early medieval Balkans, p. 141

- ^ a b The early medieval Balkans, p. 150

- ^ Pavle Ivić, The history of Serbian culture, p. 101, Porthill Publishers, 1995. Google Books link

- ^ Anne Comnene, Alexiade (Regne de L'Empereur Alexis I Comnene 1081-1118) II, pp. l57:3-l6; 1.66: 25-169. Texte etabli er traduit par B. Leib t. I-III (Paris, 1937-1945).

- ^ Dr. M. Wertner, "Ungarns Palatine und Bane im Zeit-alter der Arpaden" (Ungarische Revue, 14, 1894, 129—177)

- ^ Diplomatički zbornik kraljevine Hrvatske, Dalmacije i Slavonije, Volume 3, p. 480: "Stephanus rex Serviae monasterio St. Mariae in insula Mljet donat pagos quosdam [...]" . Google Books link

- ^ "1222, kralj srpski Stefan Prvovjenčani dava benediktinskome manastiru na Mljetu cio Mljet i Babino Polje, i na Korčuli crkvu sv. Vida, pa Janinu s Popovom Lukom i crkve sv. Stjepana i sv. Gjurgja, a u Stonu crkvu sv. [...]"

- ^ Velikonja, p. 261

- ^ Fine (1994), p. 286

- ^ a b Wolff (2003), p. 127

- ^ Fine (2006), p. 115

- ^ Јован Ердељановић (1930). О Пореклу Буњеваца.

- ^ Ćirković, 117

- ^ a b Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: occupation and collaboration. Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University. p. 390. ISBN 0-8057-3615-4.

- ^ William Safran, The secular and the sacred: nation, religion, and politics, p. 169

- ^ a b Halpern, Joel M.; Kideckel, David A. (2000). Neighbors at War. Pennsylvania State University. p. 127. ISBN 0-271-01978-6.

- ^ a b c d Anzulovic, Branimir (1999). Heavenly Serbia: from myth to genocide. C. Hurst & Co. p. 43. ISBN 1-85065-342-9.

- ^ Banac, Ivo (1984). The national question in Yugoslavia: origins, history, politics. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-8014-1675-2.

- ^ Bues, Almut (2005). Zones of fracture in modern Europe: the Baltic countries, the Balkans, and Notrhen Italy. Harassowitz Verlag. p. 101. ISBN 3-447-05119-1.

- ^ Sacred episcopacy Gornji Karlovac, article Episkop Danilo Jakšić

- ^ Fine (2006), p. 218

- ^ Europe:A History by Norman Davies (1996), p. 561.

- ^ Goffman (2002), p. 190.

- ^ a b http://books.google.se/books?id=ovCVDLYN_JgC

- ^ a b http://books.google.se/books?id=0pmkrY29qkIC

- ^ a b Ivan Ninić, Migrations in Balkan history, p. 80

- ^ a b Beller, p. 235

- ^ a b c Fine (2006), pp. 360-361

- ^ a b c Wolff, 2003, p. 2

- ^ Fine (2006), p. 356

- ^ a b Gavrilović, Danijela, "Elements of Ethnic Identification of the Serbs" from FACTA UNIVERSITATIS - Series Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History (10/2003), pp. 717-730

- ^ Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia - Manipulations with the number of Second World War victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0919817327.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert (2007). The Balkans: a post-communist history. Routledge. ISBN 0415229626.

- ^ a b (Croatian) Dunja Bonacci Skenderović i Mario Jareb: Hrvatski nacionalni simboli između stereotipa i istine, Časopis za suvremenu povijest, y. 36, br. 2, p. 731.-760., 2004

- ^ http://lnu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:205790

- ^ a b Barić, Nikica: Srpska pobuna u Hrvatskoj 1990.-1995., Golden marketing. Tehnička knjiga, Zagreb, 2005

- ^ a b Drago Kovačević, "Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu", Beograd 2003., p. 93.-94

- ^ a b Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu", Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171.-246., p. 179 [1]

- ^ a b Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95", Beograd 2002., p. 212.-222.

- ^ a b 13 mei 2007. "RSK Evacuation Practise one month before Operation Storm". Nl.youtube.com. http://nl.youtube.com/watch?v=UYjh3aAvczc. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ (Croatian) Croatian Iuridic Portal Đakula prvi svjedočio protiv Martića

- ^ a b http://www.sofiaecho.com/2009/12/31/836754_serbia-to-sue-croatia-for-genocide

- ^ a b "FACTBOX - Brief history of Croatia's rebel Serb Krajina region". Reuters. 11 March 2008. http://uk.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUKL1187232120080311?pageNumber=2&virtualBrandChannel=0.[dead link]

- ^ How Croatia and the US prevented genocide with 'Operation Storm'

- ^ a b Croatia

- ^ http://www.un.org/icty/babic/trialc/judgement/index.htm Sentencing judgement for Milan Babić

- ^ "Croatia: Operation "Storm" - still no justice ten years on". Amnesty International. 2005-08-04. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/EUR64/002/2005/en/46184632-d4c3-11dd-8a23-d58a49c0d652/eur640022005en.html. Retrieved 2008-09-29.[dead link]

- ^ http://stmichael-soc.org/background.htm

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Croatia: European Court of Human Rights to consider important case for refugee returns" (Press release). Amnesty International. 2005-09-14. http://www.amnestyusa.org/document.php?lang=e&id=ENGEUR640032005. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Negativna presuda evropskog suda u slučaju Kristine Blečić iz Zadra

- ^ HRC views on communication no. 1510/2006

- ^ ECSR decision in case no 52/2008

- ^ [3]

- ^ Human Rights Watch World Report: Croatia 2001-2003.

- ^ http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/mar/assessment.asp?groupId=34401

- ^ Daily Survey

- ^ http://www.eparhija-gornjokarlovacka.hr/Episkop-Musicki-L.htm

- ^ http://www.antikvarne-knjige.com/biografije/orfelin/zaharija_orfelin_biografija.html

- ^ http://www.eparhija-dalmatinska.hr/Publikacije-Krka13-L.htm

- ^ History of family Preradović from Gornja Krajina (Grubišno Polje etc) and their relation to the russian branch (general Nikolay Depreradovich etc), may be seen in the book published in Zagreb, Croatia in 1903, Znameniti Srbi XIX veka, year 2, 2, editor Andra Gavrilović, Zagreb 1903, p. 13. Also, book published in Belgrade in 1888, Milan Đ. Milićević, Pomenik znamenitih ljudi u srpskog naroda novijeg doba, p. 572. For the list of Preradovićs (Serbs) murderd in Jasenovac concentration camp of Independent State of Croatia (NDH) during World War II, including Preradovićs from Grubišno Polje, where father of Petar Preradović was born see (official in Croatia) Jasenovac Memorial site list of victims, where one could see a few Jovan Preradović, as was the name of Petar Preradović`s father (http://www.jusp-jasenovac.hr Spomen Područje Jasenovac), or names of 100 Preradovićs on the list of victims on the list of victims of Jasenovac Research Institute, New York, (https://cp13.heritagewebdesign.com/~lituchy/victim_search.php?field=&searchtype=contains)

- ^ Josip Runjanin

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0784884/

- ^ http://www.arhiva.glas-javnosti.rs/arhiva/2005/04/29/srpski/K05042801.shtml Prota Sava Nakićenović, O hercegnovskim Vojnovićima, Dubrovnik 1910, http://www.srpsko-nasledje.co.rs/sr-c/1998/02/article-13.html Dragomir Acović, Heraldika i Srbi, Beograd 2008, p. 335, http://www.rastko.org.yu/rastko-ukr/istorija/2003-ns/dmartinovic.pdf, http://www.scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0350-0861/2005/0350-08610553121C.pdf

- ^ http://www.skdprosvjeta.com/news.php?id=135

- ^ http://jasnasekaric.com/home.html

- ^ http://jockbio.com/Bios/Stojakovic/Stojakovic_bio.html

- ^ http://209.85.135.104/search?q=cache:VfKA_WG_LVwJ:www.rastko.org.rs/cms/files/books/46c3633ba55db.pdf+%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%BA%D0%BE+%D0%B1%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%88%D1%82%D0%B0+%D0%91%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%83%D1%88&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&client=firefox-a

- ^ http://www.serbianorthodoxchurch.com/pages/s/pavle/biography-en.html

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/475726/Svetozar-Pribicevic

- ^ http://www.ohiou.edu/~Chastain/rz/rajacic.htm

Sources

- Ilić, J. 2006, "The Serbs in Croatia before and after the break-up of Yugoslavia", Zbornik Matice srpske za društvene nauke, no. 120, pp. 253-270.

- Ivanović-Barišić, M.M. 2004, "Serbs in Croatia: Ethnological reflections", Teme, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 779-788.

- Stojanović, M. 2003-2004, "Serbs in Eastern Croatia", Glasnik Etnografskog muzeja u Beogradu, no. 67-68, pp. 387-390.

- Lajić, I.& Bara, M. 2010, "Effects of the war in Croatia 1991-1995 on changes in the share of ethnic Serbs in the ethnic composition of Slavonia", Stanovništvo, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 49-73.

- Berber, M., Grbić, B.& Pavkov, S. 2008, "Changes in the share of ethnic Croats and Serbs in Croatia by town and municipality based on the results of censuses from 1991 and 2001", Stanovništvo, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 23-62.

- Development of Astronomy among Serbs II, Publications of the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade,, Belgrade: M. S. Dimitrijević, 2002.

- Vladimir Ćorović. Illustrated History of Serbs, Books 1 - 6. Belgrade: Politika and Narodna Knjiga, 2005

- Nicholas J. Miller. Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia before the First World War, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997.

- OSCE Report on Croatian treatment of Serbs [6]

On medieval history:

- De Administrando Imperio by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, edited by Gy. Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Washington D. C., 1993

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472081497.

- John V.A. Fine. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (2006), When Ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans. A study of Identity in pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11414-x

- Ćorović, Vladimir, Istorija srpskog naroda, Book I, (In Serbian) Electric Book, Rastko Electronic Book, Antikvarneknjige (Cyrillic)

- Drugi Period, IV: Pokrštavanje Južnih Slovena

- Istorija Srpskog Naroda, Srbi između Vizantije, Hrvatske i Bugarske

- The Serbs, ISBN 0631204717, 9780631204718. Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, Google Books.

- Manfred Beller, Joseph Theodoor Leerssen, Imagology: the cultural construction and literary representation of national characters: a critical survey, Vol. 13, Studia imagologica, Rodopi, 2007. ISBN 9042023171, 9789042023178.

- Mitja Velikonja, Religious separation and political intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina, ISBN 1585442267, 9781585442263

- UNHCR document, The Status of the Croatian Serb Population in Bosnia and Herzegovina

External links

- The Serbs in the Former SR of Croatia

- Tradition chest adornment worn in Kninska Krajina

- Croatian census 2001 (see "Censuses" at Crostat Database)

- Post war life

Ethnic groups in Croatia Native nation Autochthonous national minorities Serbs · Czechs · Slovaks · Italians · Hungarians · Jews · Germans · Austrians · Ukrainians · Rusyns · Bosniaks · Slovenes · Montenegrins · Macedonians · Russians · Bulgarians · Poles · Roma · Romanians · Turks · Vlachs · AlbaniansOthers Serbian diaspora Ex-Yugoslavia

Europe Americas Canada (Toronto) • Latin America • United StatesOceania Categories:- Ethnic groups in Croatia

- European Committee of Social Rights case law

- European Court of Human Rights cases involving Croatia

- United Nations Human Rights Committee case law

- Serbian minorities

- Serbs of Croatia

- History of Dalmatia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.