- Siege of Dubrovnik

-

Siege of Dubrovnik Part of the Croatian War of Independence

Map of positions from which Dubrovnik was attacked (1991-1992)Date October 1, 1991–May 1992 Location Dubrovnik area, Croatia Result Croatian victory - Ceasefire signed

- Siege lifted

Belligerents  Yugoslav People's Army1

Yugoslav People's Army1

(Serb-controlled remnant)

Yugoslav War Navy Croatian Army

Croatian ArmyCommanders and leaders  Pavle Strugar

Pavle Strugar

(Commander, JNA 2nd Operational Group)

Miodrag Jokić

Miodrag Jokić

Milan Zec

Milan Zec

Vladimir Kovačević

Vladimir Kovačević Nojko Marinović

Nojko Marinović

(Commander of Dubrovnik defences)

Janko Bobetko

Janko Bobetko

(posted to area in 1992)Strength Between 7,500 and 20,000 men[1]

or 30,000[2]1,230 armed men at the maximum and 60 at the minimal strength, depending on the phase[2] Casualties and losses About 150 soldiers[3] Almost 100 soldiers and 82-88 civilians killed[1][4] 1 The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) formations included units of the Montenegrin Territorial Defense Forces (TO). - Log Revolution

- Pakrac

- Plitvice Lakes

- Borovo Selo

- May 1991

- Coast-91

- Opera Orientalis

- Dalj

- Osijek

- Vukovar

- (Battle

- Massacre)

- Šibenik

- The Barracks

- Banski dvori

- Široka Kula

- Dalmatian channels

- Dubrovnik

- Lovas

- Gospić

- Saborsko

- Baćin

- Otkos 10

- Škabrnja

- Erdut

- Orkan 91

- Voćin

- Vihor

- Joševica

- Bruška

- Miljevci

- Tigar

- Maslenica

- Medak Pocket

- Winter '94

- Flash

- Zagreb

- Summer '95

- Storm

- Maestral

- Timeline of all major events

- Events in Serbia

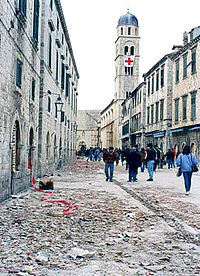

The Siege of Dubrovnik (Croatian: Opsada Dubrovnika, Serbian: Blokada Dubrovnika, meaning "Blockade of Dubrovnik", a Serbian euphemism sometimes used to play down the real nature of the military campaign[5][6][7]) is a term marking the battle and siege of the city of Dubrovnik and the surrounding area in Croatia as part of the Croatian War of Independence.[8][9][10] Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) invaded the Dubrovnik area in October 1991 from Montenegro, Bosnia and even parts of Croatia, surrounding the city in order to conquer it. The three-month bombardment of the port city was one of the events which turned international opinion against the Serbs.[11]

Dubrovnik was besieged and attacked in October 1991, with the major fighting ending in early 1992 and the Croatian counterattack finally lifting the siege and liberating the area in mid-1992, despite suffering heavy losses. The heaviest shelling of the city was on St. Nicholas Day, on December 6, 1991, when thirteen civilians were killed, which represented the greatest number of civilian deaths on a single day during the siege.[4] According to the United Nations report, the siege caused at least 15,000 refugees, of which 7,000 were evacuated by sea in October 1991, whereas the city itself was without electricity or fresh water for at least two months, until the end of December 1991, since the JNA forces bombarded the district's electrical grid. The population at that time was dependent on ships for their water supply.[4]

At the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the prosecution alleged "It was the objective of the Serb forces to detach this area from Croatia and to annex it to Montenegro."[12]

Contents

Background

Dubrovnik is an old city located in the southernmost part of Dalmatia. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and tourist destination, and under Communist Yugoslavia was demilitarized as it was considered that a military presence would not go hand to hand with tourism. When Croatia voted for independence in 1991, it was therefore one of the few major cities in Croatia not to have major JNA military forces in the area, which spared it during the Battle of the Barracks of September. In 1991, the city had a population of approximately 50,000 of whom 82.4% were Croats, 6.8% were Serbs, and 4% were Muslims.[13]

The geographical position of the city was somewhat problematic. With the land borders between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and Montenegro (in 1991 both still part of Yugoslavia), Dubrovnik and the surrounding area found itself isolated. The southernmost part of Croatia is separated by the BiH's sea corridor at Neum. Furthermore, the geographical area around the city is very mountainous and unsuitable for military operations, creating a significant supply problem which was to limit the amount of forces involved. This meant that, in the case of a JNA attack from the neighbouring republics, Croatia's assistance would be limited to what could be transported to the area by sea.

At the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), prosecutor Carla Del Ponte claimed that the purpose of the attack was to annex the area to Serbia and Montenegro by proclaiming a new Republic of Dubrovnik.[14] Nojko Marinović claims that Dubrovnik was offered to become an autonomous republic within an enlarged Serbia.[15] Former Yugoslav Ambassador to the European Union (EU), Mihailo Crnobrnja, speculated that the rationale for the siege was to gain an important bargaining chip to force Croatia to lift its blockades of JNA barracks. He also suggested that Montenegro may have wanted to hold Dubrovnik ransom for Croatian recognition of Prevlaka, a peninsula south of Dubrovnik, as Montenegrin territory.[16]

Serbian propaganda activities

Main article: Propaganda in the Yugoslav Wars"I was confused after hearing about 30,000 Ustashas on the move! TV Belgrade and Montenegrin TV provided the news and I, like a child, was frightened... Imagine how others felt when even I, a university professor, fell for it."

Novak Kilibarda about the war propaganda.[17]Before the Siege of Dubrovnik, General Pavle Strugar[18] made a concerted effort at misrepresenting the military situation on the ground and exaggerated the "threat" of an Croatian attack on Montenegro by "30,000 armed Ustashas and 7000 terrorists, including Kurdish mercenaries".[1] This propaganda was widely spread by the state-controlled media of Serbia and Montenegro.[19]

"Pobjeda"’s 1991 editorials tried to stage that "Croatia and Slovenia chose the war by opting for independence". This attitude was embraced by leading Montenegrin politicians at the time. Svetozar Marović saw the causes of the Yugoslav breakup in “the continuity of an aggressive imperialist Catholicism”.[17] All this helped to instrumentalize the public and gave politicians a free hand to start the invasion of the Dubrovnik area.[17]

During the Siege of Dubrovnik, while the Yugoslav army shelled the Croatian port town, Radio Television of Serbia showed Dubrovnik with columns of smoke explaining that the local people were burning automobile tires to simulate destruction of the city.[5][20]

The siege

Opposing forces

Croatian military forces in the area at September were virtually non-existent[4][15] and were severely outgunned as the heaviest weapons available to them were four Soviet ZIS 76 millimeter artillery guns from 1942 of which only one had a telemetric device. The defenders also received two 85mm guns from the island of Korčula as well as three 120mm mortars.[21][22] One of the reasons for their disadvantage was Tuđman's order from August 1991 which stipulated that no "defensive measures were to be taken in the region" of Dubrovnik, which was based on assurances of Veljko Kadijević and Milošević that the JNA would not attack that city.[15]

The defenders included just one locally conscripted unit, the 163rd Infantry Brigade, which — along with local police forces and volunteers — numbered less than 1,500 men and had no tanks or heavy guns. Towards the end of the year, the defenders were reinforced with the IX (9th) HOS Infantry Battalion of less than 500 men.

These were pitted against several brigades of the JNA and Montenegro Territorial Defence Force of between 7,500 and 20,000 men, with tanks and artillery elements of the Naval District Corps and assorted other Corps formations of south Bosnia and Montenegro. The attack at the time was portrayed as an entirely Montenegrin affair (despite the mixed nationality of JNA troops, and Serb guidance, Montenegrins made the majority of troops) and was therefore presented in Montenegro as "War for Peace". Montenegrin prime minister Milo Đukanović said at the time that Montenegro had to definitively settle its borders with Croatia and fix the mistakes made by "Bolshevik cartographers".[23]

City map with marked damage from the shelling by the Yugoslav People's Army.

City map with marked damage from the shelling by the Yugoslav People's Army.

JNA officers made a concerted effort at misrepresenting the military situation on the ground and exaggerated the "threat" of an attack on Montenegro by "30,000 armed Ustashas and 5,000 terrorists, including Kurdish mercenaries". There were said to be no mercenaries on the Croat side, and only one foreigner at all: a Dutchman, who was married to a lady from Dubrovnik and who was there during the war. He volunteered to join the Croatian army.[1][15]

Initial attacks

By October 1991, war had already started throughout Croatia. On 1 October 1991, JNA forces from Montenegro (swelled by mobilization called on 16 September in Montenegro) and south BiH advanced to attack the surrounding area and occupied Prevlaka, Konavle, Cavtat and the entire area around Dubrovnik, including the important international airport. The operation involved some amphibious landings.[24] The airport was looted of valuable equipment which was taken to Montenegro - after independence in 2006, Montenegro has agreed to pay reparations for this.

On the way to attack Dubrovnik, JNA forces from Bosnia leveled the Croatian forces in the village of Ravno (in Bosnia) to the ground, making it the first casualty of the Bosnian War which officially started only six months later.

A combination of stiff resistance and international attention blocked the JNA's total attack and occupation of the city. The JNA occupied high terrain around the city instead, placing artillery there to shell the city - thus, the siege had started. At the same time, the Yugoslav Navy was actively involved in the bombardment, conducting amphibious operations and maintaining a sea blockade while shelling the city from the Adriatic Sea. Food, water and electricity supply to the city was cut during the earliest stages of the siege. The city was also crowded with 55,000 refugees from other war-torn areas in Croatia who had sought a safe haven there.[21]

Siege and blockade

"All armies in the past did their best and refused to wage war or to target and to bomb the city of Dubrovnik. It was simply impossible for anyone to attack and demolish Dubrovnik. In the 1800s, Dubrovnik was captured by Napoleon, but without a fight. The Russian fleet of Admiral Senyavin came to attack Dubrovnik but they lowered their guns and gave up on the attack. There was not a single shell or bullet fired at Dubrovnik. That's Dubrovnik's history, and that indicates the level of the human civilisation, the level of respect afforded to Dubrovnik. What we did is the greatest shame that was done in 1991."[25]

Nikola Samardžić, former Montenegrin foreign minister, during Strugar's trial at the ICTY.The siege had immediately raised attention, as western reporters took pictures of the shelling (especially the Old City of Dubrovnik - a UNESCO World Heritage Site) - which drew international criticism of the JNA forces. The siege was heavily present in the international media and journalists have been heavily criticised for focusing and exaggerating damage to the old city to encourage military intervention, instead of focusing on human casualties.[26] The concern with buildings over civilian deaths pushed the pivotal and much more brutal Battle of Vukovar out of public view.[26] Even before the siege, the international community attempted several treaties to limit JNA advances into overwhelmingly Croat areas, yet these were systematically broken by JNA forces.[1]

Negative though the international reaction was, it did nothing to quell the brutal bombardment, however, and the shelling continued until December. If the area around Dubrovnik is excluded, the Old Town itself was shelled on 23 October, 30 October (when 6 civilians were killed, including a mother and her child), 1 November, 2 November (when refugees were wounded), 3 November, 4 November, 8-13 November, 2 December and 6 December.[4]

Towards the end of the year, the Croatian defenders staged a small counterattack aiming to displace the JNA from the surrounding mountains, but this did not end the bombardment entirely. Yugoslav poet Milan Milišić was one of the first casualties of shelling, on 5 October 1991. The Yugoslav Navy and Army also increased their pressure on neighbouring Croatians ports such as Slano, where they burned and destroyed the small transport Perast. Three seamen were killed in the attack, while the rest of the crew escaped to Dubrovnik. The ship was later found adrift by members of the Croatian Navy off Šipan island.[27]

In November, the ferryboat Slavija, leading a large convoy of 40 fishing and tour boats docked at the town, taking 2,000 refugees from the city up the Croatian coast. The convoy, called by the Croatians Libertas or "Freedom 's convoy", had been initially stopped by the Yugoslav frigate JRM Split between the islands of Brač and Šolta and the next day by Yugoslav patrol boats off Korčula,[28] but after several hours of negotiations between Yugoslav President Stjepan Mesić, aboard the Slavija, and his deputy minister of defense, the flotilla was allowed to proceed.[29][30]

On 11 November an old Maltese-flagged coaster, the Euro River, manned by a Croatian crew and bound for Ploce, a port located some miles north of Dubrovnik, was sunk by gunfire at the position 43°19′N 16°9′E / 43.317°N 16.15°E, not far from the area where the Slavija convoy was stopped for the first time. All people aboard were safely rescued.[31] At the same period, a runabout from the Dubrovnik marina, the Sveti Vlaho (St. Blaise) was requisitioned by the Croatian authorities, thus becoming one of the first operational vessels of the new Croatian Navy as it represented the first craft of the Armed Boats Squadron Dubrovnik. She was outfitted with armor-plates and armed with machine guns. The Sveti Vlaho carried out several blockade-running missions smuggling weapons, ammunition and supplies into the besieged city before being hit and crippled by a 9K11 Malyutka missile on 6 December.[32][33] The vessel has since been restored and is currently on display at the city's port.[34]

On 6 December, the heaviest shelling was reported on what came to be known as the St. Nicholas Day Bombardment, and 13 civilians were killed.[4] During the siege, several yachts moored at the old harbour were destroyed or damaged by wire-guided missiles,[35] while some larger ships at the port of Gruž, like the ferryboat Adriatic[36] and the American-owned sailing ship Pelagic[37] were set ablaze and destroyed by gunfire. By the end of December, Croatian Navy and coastal artillery had successfully repelled JNA Navy forces along Dalmatia, and the Navy withdrew to Montenegro's naval base at Boka Kotorska. The situation on the ground was still unfavorable, though. The last ceasefire went into effect at the end of the year and the shelling ended by 1992.

Croatian counterattack

As part of the ceasefire agreement, the JNA formally left Croatia and moved to Bosnia and Herzegovina where the Bosnian War was to start in April - the notable exception was Dubrovnik where there weren't enough local Serb formations as in other parts of Croatia to replace them, so the JNA continued its presence there. Since many of the units involved in attacks on Dubrovnik were originally from Army formations stationed in Bosnia (specifically, Trebinje Corps), these were now returned to their home commands, as JNA forces planned a general offensive on the nearby BiH city of Mostar.

The units left behind near Dubrovnik were now to reserve strength and the Croatian army took advantage of the altered situation by redeploying elements of its elite guard brigades (1st, 2nd and 4th brigades) to the area, forming a command HQ under Janko Bobetko in April and starting a successful offensive which broke the blockade on 26 May 1992. During the course of the next two months, Operations Čagalj and Tigar were launched to push the remaining forces away from the city and liberate the entire surrounding area, which was achieved by the end of July. The important Prevlaka area was also taken - which effectively meant a blockade of the JNA Navy in Boka - but was recaptured by Montenegro forces later on. Following this, both sides agreed for United Nations supervision of the area, ending the battle for Dubrovnik.

Aftermath

In 1991, the American Institute of Architects condemned the bombardment of buildings.[38] The Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments, in conjunction with UNESCO, found that of the 824 buildings in the Old Town, 563 (or 68.33 %) had been hit by projectiles in 1991 and 1992. Nine buildings were completely destroyed by fire. In 1993, the Institute for the Rehabilitation of Dubrovnik and UNESCO estimated the total cost for restoring public, private and religious buildings, streets, squares, fountains, ramparts, gates, and bridges at US$9,657,578. By the end of 1999, over $7,000,000 had been spent on restoration.[14]

Croatian prisoners of war from the attack on Dubrovnik and its hinterland were taken by the Yugoslav People's Army were taken to detention centers, notably the Morinj camp near Kotor, Montenegro, and a prison near Bileća, Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they were held until 1992.

The city and the area recovered remarkably well from the war, and the city is once again a favorite tourist destination. Prevlaka has been returned from UN supervision to Croatian control and the newly independent Montenegro has expressed its wish for improving relations with Croatia. However, there is still no agreement between the two countries involving war reparations. In 2000, Milo Đukanović as president of Montenegro apologized to Croatia for the siege.[39] In 2007, Montenegrin filmmaker Koča Pavlović released Rat za mir about the role of Montenegrin officials in the siege.[40]

War crime charges

From October 1, 1991 until December 7, 1991, Slobodan Milosevic, acting alone or in concert with other known and unknown members of the joint criminal enterprise, planned, instigated, ordered, committed, or otherwise aided and abetted the planning, preparation, or execution of a military campaign directed at the city of Dubrovnik and its surroundings in order to achieve the forcible removal of its non-Serb population. In this time period launched an extensive military attack on the coastal regions of Croatia between the town of Neum, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the north-west and the Montenegrin border in the south-east. It was the objective of the Serb forces to detach this area from Croatia and to annex it to Montenegro. While the Serb forces seized the territory to the south-east and north-west of the city of Dubrovnik within two weeks, the city itself was under attack throughout the time alleged in this indictment. During an unlawful extensive shelling campaign conducted from high ground east and north of Dubrovnik, forty-three Croat civilians were killed and numerous others wounded.[41]

— War Crimes Indictment against Milosevic and others

In 2001, at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), prosecutor Carla Del Ponte charged four JNA commanders for their role in the siege: Pavle Strugar, Miodrag Jokić, Milan Zec, and Vladimir Kovačević.[14]

- General Pavle Strugar was sentenced to eight years for his role in the shelling of the city.[42]

- Miodrag Jokić (commander of JNA Naval District) was sentenced to seven years.[43]

- The indictment against Yugoslav Navy Captain Milan Zec was withdrawn in July 2002.[44]

- Vladimir Kovačević (commander of Third Battalion 472nd Motorized JNA Brigade) was accused together with Strugar for war crimes, but his case was transferred to the Courts of Serbia. He was found to be unable to stand trial due to insanity and was transferred to a mental asylum.[45]

Croatian authorities issued arrest warrants for numerous former JNA officers and commanders. In 2011, Božidar Vučurević, former war-time mayor of Trebinje, was arrested at a border crossing by Serb officials based on Croatian charges of bombing Dubrovnik.[46]

Movies and documentaries

- "War for Peace" (2007); a Montenegrin documentary by Koča Pavlović.[17]

- "War for Dubrovnik" (2010); a Montenegrin documentary by Snežana Rakonjac.[47]

See also

- Operation Coast-91

- Battle of the Dalmatian channels

References

- ^ a b c d e Pavlović, Srđa (2005). "Reckoning: The 1991 Siege of Dubrovnik and the Consequences of the "War for Peace"". Space of Identity 5 (1). Accessed September 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Tragovi TV Debate Show on Croatian Radio Television, May 30, 2007. The Show screened Montenegran documentary War for Peace which cites 30,000 JNA men and 700 Croatian defenders. In the show, General Nojko Marinović also cited Croatian defenders as "1230 at maximum and about 60 at its lowest strength"

- ^ ICTY Transcripts: Testemony of Petar Poljanić, Mayor of Dubrovnik. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 4 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Annex XI.A : The battle of Dubrovnik. United Nations Commission of Experts (28 December 1994). University of the West of England. Accessed 7 September 2009.

- ^ a b Perlez, Jane (10 August 1997). "Serbian Media is One-Man Show". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A00EFDE133CF933A2575BC0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all#IVC. "People here still don't believe that Dubrovnik was shelled, said Veran Matic, the founder of B-92, the only independent radio network in Serbia. The Yugoslav army attacked the Croatian port town in 1991. Belgrade TV showed Dubrovnik with columns of smoke and then said that it was caused by the local people burning tires, he said."

- ^ "ICTY Pavle Strugar Transcript". The Hague: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 30 June 2004. p. 7047. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/strugar/trans/en/040630IT.htm. Retrieved 13 August 2011. "Does it say anywhere in this directive, in that document, that the assignment of the units of the 2nd Operational Group is to capture the town of Dubrovnik? Or does it speak only of a blockade? - A. Blockade only."

- ^ "ICTY Pavle Strugar Transcript". The Hague: International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. 14 May 2004. p. 6548, 6565. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/strugar/trans/en/040514IT.htm. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "General denies Dubrovnik charges". CNN. October 25, 2001. http://edition.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/europe/10/25/hague.strugar/index.html?iref=allsearch. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Julijana Mojsilovic (November 13, 2001). "Admiral gives himself up to UN tribunal". Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2001/nov/13/warcrimes?INTCMP=SRCH. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "Dubrovnik 1991-1992". UNESCO. February 1993. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0009/000944/094464eb.pdf. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "Charges over Dubrovnik bombing". BBC News. Friday, 2 March 2001. http://cdnedge.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/1196879.stm. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Investigative Summary. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 4 September 2009.

- ^ Reckoning: The 1991 Siege of Dubrovnik and the Consequences of the “War for Peace”

- ^ a b c Full Contents of the Dubrovnik Indictment made Public. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (2 October 2001). Accessed 4 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d Armatta 2010, p. 184-187

- ^ Crnobrnja, Mihailo (1996). The Yugoslav Drama (2 ed.). p. 172. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-1429-5.

- ^ a b c d Srđa pavlović. "Reckoning: The 1991 Siege of Dubrovnik and the Consequences of the “War for Peace" (p. 76)". http://www.yorku.ca/soi/_Vol_5_1/_HTML/Pavlovic.html. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Svjedok: Strugar je lagao da 30.000 ustaša napada Boku

- ^ Attack on Dubrovnik: 30 000 Ustasa marsira na Crnu Goru ("Rat za mir" documentary)

- ^ "ICTY Serbian TV accuses Croats of burning tyres in Dubrovnik siege". http://www.un.org/icty/transe42/040303IT.htm#IVC.

- ^ a b Blaskovich 1997

- ^ Museum of the imperial fort above Dubrovnik

- ^ Grujić, Dragoslav (14 November 2002). Fleksibilna britva. Vreme. Accessed 7 September 2009.

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina (2006). The three Yugoslavias: state-building and legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press, p. 409. ISBN 0-253-34656-8

- ^ "Pavle Strugar Transcript 040123ED (p. 1145)". ICTY. January 23, 2004. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/strugar/trans/en/040123ED.htm. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Joseph Pearson, 'Dubrovnik’s Artistic Patrimony, and its Role in War Reporting (1991)' in European History Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 2, 197-216 (2010)

- ^ Ratgona Mučenica "Perasta" Slobodna Dalmacija, July 6, 1999 (Croatian)

- ^ Mesic, Stjepan (2004). The demise of Yugoslavia: a political memoir. Central European University Press, pp. 389-390. ISBN 963-9241-71-7

- ^ Peace Flotilla Due to Dock in Dubrovnik Los Angeles Times, 31 October 1991

- ^ Binder, David (15 November 1991). Refugees Pack Boat Out of Dubrovnik. The New York Times. Accessed 7 September 2009.

- ^ Hooke, Norman (1997). Maritime casualties, 1963-1996. LLP, p. 203. ISBN 1-85978-110-1

- ^ Croatian international relations review (1997) Issues 6-13. Institute for Development and International Relations, Zagreb, p. 41

- ^ "Sveti Vlaho" u punom sjaju Slobodna Dalmacija newspaper, 6 December 2001 (Croatian)

- ^ Case No. IT-01-42. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 6 September 2009.

- ^ Silber, Laura and Little, Alan: Yugoslavia: death of a nation. Penguin Books, p. 184. ISBN 014026263

- ^ Steamship Historical Society of America: Steamboat bill: journal of the Steamship Historical Society of America, Volume 49 (1992)

- ^ Maritime Law Association of the United States, Association of Average Adjusters of the United States: American maritime cases, Volume 2 (1994)

- ^ Zaknic, Ivan (November 1992). "The Pain of Ruins: Croatian Architecture under Siege". Journal of Architectural Education (Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture) 46 (2): 121.

- ^ Thorpe, Nick (25 June 2000). Djukanovic 'sorry' for Dubrovnik bombing. BBC. Accessed 7 September 1991.

- ^ "War for Peace - Part 1". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aExEw4Kd8Ac. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Indictment against Milosevic and others

- ^ Judgement in the Case the Prosecutor v. Pavle Strugar. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 6 September 2009.

- ^ Judgement in the Case the Prosecutor v. Miodrag Jokic. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 6 September 2009.

- ^ Indictment Against Milan Zec Withdrawn. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 6 September 2009.

- ^ Vladimir Kovačević. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Accessed 6 September 2009.

- ^ "Former Bosnian Serb mayor arrested for bombing Dubrovnik" (in English). Belgrade: Xinhuanet. April 4, 2011. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/world/2011-04/05/c_13813203.htm. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Rat za mir". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pAePRD5vjp8. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

Bibliography

- Armatta, Judith (2010) (in English). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Duke University Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=pXygFoqg-G0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=twilight+of+impunity&hl=en&ei=R-pPTqLQMMPo-ga5oeX2DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Blaskovich, Jerry (1997). Anatomy of Deceit: An American Physician's First-Hand Encounter with the Realities of the War in Croatia. Dunhill Publishing. ISBN 0935016244, 9780935016246. http://books.google.hr/books?id=ngkIAAAACAAJ.

External links

- Second Amended Indictment against P. Strugar and V. Kovačević, includes a list of damaged religious, art and education buildings and monuments in the UNESCO-protected old city

- Publication "Dubrovnik: War for peace" on the siege of Dubrovnik, published by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia (Serbian)

- United Nations report on the battle

Categories:- 1991 in Croatia

- 1992 in Croatia

- Dubrovnik

- Battles involving Montenegro

- Battles involving Serbia

- Conflicts in 1991

- Conflicts in 1992

- Maritime incidents in 1991

- Battles of the Croatian War of Independence

- Sieges

- War crimes in former Yugoslavia

- Serbian war crimes

- 1991 in Yugoslavia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.