- Role of the media in the Yugoslav wars

-

Picture of a "Serbian boy whose whole family was killed by Bosnian Muslims", published by Večernje novosti during the Bosnian War.[1]

Picture of a "Serbian boy whose whole family was killed by Bosnian Muslims", published by Večernje novosti during the Bosnian War.[1]

Orphan on the mother's grave. A 1888 painting by Uroš Predić.

Orphan on the mother's grave. A 1888 painting by Uroš Predić.

During the Yugoslav Wars propaganda was used as a military strategy by governments of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and, to a lesser extent, Croatia. Mostly it was used in the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, propaganda was used in Croatian war and Kosovo war as well.

Serbian propaganda

In the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia indictments of former Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević, one of his contributions to the joint criminal enterprise to ethnic cleansing of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina was use of the Serbian state-run media to create an atmosphere of fear and hatred among Yugoslavia's Orthodox Serbs by spreading "exaggerated and false messages of ethnically based attacks by Bosnian Muslims and Catholic Croats against Serb people..."

Background

- Đorđe Martinović story published by Politika in May 1985

- Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts published by Večernje Novosti in September 1986

Milošević's control of media in Serbia

Milošević began his efforts to gain control over the media in 1986-87,[2] a process which was complete by summer of 1991. In 1992 Radio Television Belgrade, together with Radio Television Novi Sad (RTNS) and Radio Television Pristina (RTP) became a part of Radio Television of Serbia, centralized and closely governed network aimed to be a loudspeaker for Miloševic and his policy. During the 1990s, Dnevnik (Daily news) was used to glorify "wise politics of Slobodan Milošević" and to attack "servants of Western powers, forces of chaos and despair", i.e., Serbian opposition.[3]

According to the witness called by the ICTY's Office of the Prosecutor, Professor Renaud De la Brosse, Senior Lecturer at the University of Reims, Serbian authorities used media as a weapon in their military campaign. "In Serbia specifically, the use of media for nationalist ends and objectives formed part of a well thought through plan - itself part of a strategy of conquest and affirmation of identity."[4] According to de la Bosse, nationalist ideology defined the Serbs partly according to a historical myth, based on the defeat of Serbia by the Ottoman forces at the battle of Kosovo in 1389 and partly on the genocide suffered by Serbs during the Second World War at the hands of the Independent State of Croatia. Croatian will for independence fed the flames of fear, especially in Serb majority regions of Croatia. According to de la Bosse, the new Serbian identity became one in opposition to the "other" - Croats (collapsed into Ustashe) and Muslims (collapsed into Turks).[4] Even Croatian democracy was dismissed since ‘Hitler came to power in Germany within the framework of a multi-party mechanism but subsequently became a great dictator, aggressor and criminal’[5][6]

While Milošević, until the run up to the Kosovo war, allowed independent print media to publish, their distribution was limited. His methods of controlling the media included creating shortages of paper, interfering with or stopping supplies and equipment, confiscating newspapers for being printed without proper licenses, etc.. For publicly owned media, he could dismiss, promote, demote or have journalists publicly condemned. In 1998, he adopted a media law which created a special misdemeanor court to try violations. It had the ability to impose heavy fines and to confiscate property if they were not immediately paid.[4] According to the report by de la Brosse, Milosevic-controlled media reached more than 3.5 million people every day. Given that and the lack of access to alternative news, de la Brosse states that it is surprising how great the resistance to Milosevic's propaganda was among Serbs - evidenced not only in massive demonstrations in Serbia in 1991 and 1996-97 both of which almost toppled the regime, but also widespread draft resistance and desertion from the military.[4]

De la Brosse describes how RTS (Radio Television of Serbia) portrayed events in Dubrovnik and Sarajevo: "The images shown of Dubrovnik came with a commentary accusing those from the West who had taken the film of manipulation and of having had a tire burnt in front of their cameras to make it seem that the city was on fire. As for the shells fired at Sarajevo and the damage caused, for several months it was simply as if it had never happened in the eyes of Serbian television viewers because Belgrade television would show pictures of the city taken months and even years beforehand to deny that it had ever occurred." The Serbian public was fed similar disinformation about Vukovar, according to former Reuters correspondent Daniel Deluce, "Serbian Radio Television created a strange universe in which Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, had never been besieged and in which the devastated Croatian town of Vukovar had been 'liberated'."[4]

ICTY sentencing judgement for Milan Babić which has been first president of Republic of Serbian Krajina, a self-proclaimed Serbian dominated entity within Croatia will declare:

"Babic made ethnically based inflammatory speeches during public events and in the media that added to the atmosphere of fear and hatred amongst Serbs living in Croatia and convinced them that they could only be safe in a state of their own. Babic stated that during the events, and in particular at the beginning of his political career, he was strongly influenced and misled by Serbian propaganda, which repeatedly referred to an imminent threat of genocide by the Croatian regime against the Serbs in Croatia, thus creating an atmosphere of hatred and fear of the Croats. Ultimately this kind of propaganda led to the unleashing of violence against the Croat population and other non-Serbs."[7]

Željko Kopanja, editor of the independent newspaper Nezavisne Novine, was seriously hurt by a car bomb after publishing stories detailing atrocities committed by Serbs against Bosniaks during the Bosnian war. He believed the bomb was planted by Serbia's security services to stop him from further publishing stories. An FBI investigation supported his suspicions.[8]

Serbian propaganda cases

Some of the cases of Serbian manipulation include:

"Pakrac massacre" case

Main article: Battle of PakracDuring the Battle of Pakrac, Serbian newspaper "Večernje Novosti" reported that about 40 Serb civilians were killed in Pakrac on March 2, 1991 by the Croatian forces. The story was widely accepted by public and some ministers in Serbian government (e.g. Dragutin Zelenović). Attempts to confirm the report in other media from all 7 municipalities with the name Pakrac throughout the former Yugoslavia failed.[9]

"Vukovar baby massacre" case

Main articles: Vukovar massacre and Vukovar children massacreDay before the execution of 264 Croatian prisoners of war's and civilians in the Ovčara massacre, Serbian media released the news of 40 Serb babies being slaughterd in Vukovar. Dr. Vesna Bosanac, the head of Vukovar hospital from which the Croatian POW's and civilians were taken, said she believed the story of slaughtered babies was released intentionally to make Serb nationalists more angry thus inciting them to execute Croats.[10]

"Dubrovnik 30,000 Ustashas" case

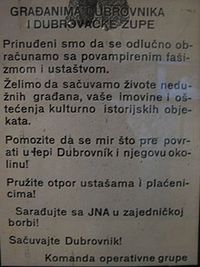

Main articles: Siege of Dubrovnik and UstashaBefore the Siege of Dubrovnik, JNA officers (namely Pavle Strugar[11]) made a concerted effort at misrepresenting the military situation on the ground and exaggerated the "threat" of an Croatian attack on Montenegro by "30,000 armed Ustashas and 7000 terrorists, including Kurdish mercenaries".[12] This propaganda was widely spread by the state-controlled media of Serbia and Montenegro.[13]

Actually, Croatian military forces in the area at September were virtually non-existent.[14] The defenders included just one locally conscripted unit, numbered less than 1,500 men and had no tanks or heavy guns. Also, there were no mercenaries on the Croat side.[12]

"Dubrovnik burning tires" case

Main article: Siege of DubrovnikDuring the Siege of Dubrovnik in 1991, while the Yugoslav army shelled the Croatian port town, Radio Television of Serbia showed Dubrovnik with columns of smoke explaining that the local people burning automobile tires to simulate destruction of the city.[15][16]

Operation Opera Orientalis

Main article: Operation Opera OrientalisDuring the secret intelligence Operation Opera Orientalis, while the Serb-controlled Yugoslav Air Force bombed Jewish cemetery and Jewish Community Center in Zagreb in August 1991, Serbian media repeatedly made false accusations in which Croatia was connected with World War II, nazism and anti-Judaism with the aim to discredit the Croatian demands for independence in the West.[17][18]

1992 Tuđman quote about "Croatia wanting the war"

The Serbian media emphasized that Croatian president Franjo Tuđman started the war in Croatia. In order to corroborate that notion, the media repeatedly referenced his speech in Zagreb, on the 24 May 1992, claiming that he allegedly said: "There would not have been a war had Croatia not wanted one".[19] During their trials at the ICTY, Slobodan Milošević and Milan Martić also frequently resorted to that alleged Tuđman quote in order to prove their innocence.[20]

However, the ICTY prosecutors obtained the integral tape of his speech and played it in its entirety during Martić's trial on the 23 October 2006, proving that Tuđman never said that Croatia "wanted the war".[21] Upon playing that tape, Borislav Đukić had to admit that Tuđman did not say that.[21] The quote is actually the following: "Some individuals in the world who were not friends of Croatia claimed that we too were responsible for the war. And I replied to them: Yes, there would not have been a war had we given up our goal to create a sovereign and independent Croatia. We suggested that our goal should be achieved without war, and that the Yugoslav crisis should be resolved by transforming the federation, in which nobody was satisfied, particularly not the Croatian nation, into a union of sovereign countries in which Croatia would be sovereign, with its own army, own money, own diplomacy. They did not accept."[22]

"Bosnian mujahideen" case

Main article: Bosnian mujahideenSerbian propaganda during the Bosnian war portrayed the Bosnian Muslims as violent extremists and fundamentalists.[23] After series of massacres of Bosniaks, a few hundreds (between 300[24][25] and 1,500[24]) of Arabic-speaking volunteers from the Middle East and North Africa, called Mujahideen, came into Bosnia in the second half of 1992 with the aim of helping their Muslim brothers.[26] Serb media fabricated much bigger numbers of mujahideens presenting them as terrorists a huge threat to Europe,[25] in order to inflame anti-Muslim hatred among Serbs.[27][28] Although Serbian media created much controversy about alleged war crimes committed by them, no indictment was issued by ICTY against any of these foreign volunteers.

"Prijedor monster doctors" case

Main article: Prijedor massacreJust before the Prijedor massacre of Bosniak and Croat civilians, Serb propaganda characterising prominent non-Serbs as criminals and extremists who should be punished for their behaviour. Dr. Mirsad Mujadžić, Bosniak politician, was accused of injecting drugs into Serb women making them incapable of giving birth to male children, thus reducing the birth rate among Serbs, and dr. Željko Sikora, a Croat, referred to as the Monster Doctor, was accused of making Serb women abort if they were pregnant with male children and of castrating the male babies of Serbian parents.[27][29] Moreover, in a "Kozarski Vjesnik" article dated June 10, 1992, Dr. Osman Mahmuljin was accused of deliberately having provided incorrect medical care to his Serb colleague dr. Živko Dukić, who had a heart attack.

Mile Mutić, the director of Kozarski Vjesnik and the journalist Rade Mutić regularly attended meetings of Serb politicians (local authorities) in order to get informed about next steps of spreading propaganda.[27][28]

"Markale conspiracy" case

Main article: Markale massacresThe Markale massacres were two artillery attacks on civilians at the Markale marketplace, committed by the Army of Republika Srpska during the Siege of Sarajevo.[30][31] Encouraged by the initial UNPROFOR report, Serbian media claimed that the Bosnian government had shelled its own civilians in order to drag the Western powers to intervene against the Serbs.[32][33][34] However, in January 2003, the War Crime Tribunal concluded that the massacre was committed by Serb forces around Sarajevo.[35] Although widely reported by the international media, the verdict was ignored in Serbia itself.[32]

Lions from Pionirska Dolina case

Lions from Pionirska Dolina case is the most bizarre case related to propaganda during Yugoslav wars. During the Siege of Sarajevo, Serb propaganda was trying to justify the siege at any cost. As the result of that effort Serbian national television gave a report about Serb children being given as a food for lions in Sarajevo ZOO called Pionirska Dolina by Muslim extremists.[36][37]

Executions of Tuzla

Shortly after the events of the Tuzla column, the Serbian national television, reported the gathering and execution of Bosnian Serbs living in Tuzla at Stadium Tusanj, and disposal of the bodies in the nearby river Jala. No pictures of the selections, executions or carcasses, have been given by the Serb television, nor have been ever found. However the majority of Serbs during and after the war, still believe it happened.

Propaganda as part of the indictment against Milošević

According to the prosecution at the ICTY trial of Milosevic, Serbian television and radio's repetitive use of pejorative descriptions, such as "Ustashe hordes", "Vatican fascists", "Mujahedin fighters", "fundamentalist warriors of jihad", and "Albanian terrorists", became part of common usage. Unverified stories, presented as fact, were turned into common knowledge, for example, that Bosniaks were feeding Serb children to animals in the Sarajevo zoo. According to de la Brosse, the easier it was to fear other ethnic groups, the easier to justify their expulsion or killing.[4]

Two members of the Federal Security Service (KOG) testified for the Prosecution in Milosevic's trial about their involvement in Milosevic's propaganda campaign. Slobodan Lazarevic revealed alleged KOG clandestine activities designed to undermine the peace process, including mining a soccer field, a water tower and the reopened railway between Zagreb and Belgrade. These actions were blamed on Croats. Mustafa Candic, one of four assistant chiefs of KOG, described the use of technology to fabricate conversations, making it sound as if Croat authorities were telling Croats in Serbia to leave for an ethnically pure Croatia. The conversation was broadcast following a Serb attack on Croatians living in Serbia, forcing them to flee. He testified that the propaganda war was code named "Operation Opera, see Opera orientalis which included bombing of a Jewish cemetery and the Jewish Community Center in Zagreb, Croatia." He also testified to another instance of disinformation involving a television broadcast of corpses, described as Serb civilians killed by Croats. Candic testified that he believed they were in fact the bodies of Croats killed by Serbs, though this statement has not been verified.[4][38]

Propaganda as a war crime in the Šešelj's case

Propaganda as a war crime (incitement to genocide) is the subject in the recent indictment of Vojislav Šešelj, head of the Serbian Radical Party and an active player throughout the wars in the former Yugoslavia. According to the indictment, Seselj bears individual criminal responsibility for instigating crimes, including murder, torture and forcible expulsion on ethnic grounds. It reads, "By using the word 'instigated', the Prosecution charges that the accused Vojislav Seselj's speeches, communications, acts and/or omissions contributed to the perpetrators' decision to commit the crimes alleged." [39][40]

Backlash

During the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, building of Radio Television of Serbia in Belgrade was targeted.[41][42]

When Milošević's regime was finally overthrown in October 2000, RTS was a primary target of demonstrators. After attacking the Parliament, the demonstrators headed for the RTS building.[4]

In Serbia, journalists are still[when?] being threatened and some were even killed. Mostly investigative journalists are targeted.[43][editorializing]

Serbian State TV Apology

On 23 May 2011 Radio Television of Serbia (RTS) issued an official apology for the way their programming was misused for spreading propaganda and discrediting political opponents in the 1990s, and for the fact that their programming had "hurt the feelings, moral integrity and dignity of citizens of Serbia, humanist-oriented intellectuals, members of the political opposition, critically minded journalists, certain minorities in Serbia, minority religious groups in Serbia, as well as certain neighbouring peoples and states."It also states that there was no doubt that the state media were under direct control of the late President of Serbia Slobodan Milosevic.Serbian state media were used by Milosevic as a war tool for inciting hatered and deceiving his people in order to get support needed to continue with the wars in the Balkans. [44]

Croatian propaganda

Croats also used propaganda against Serbs[citation needed] throughout and against Bosniaks during the 1992-1994 Croat-Bosniak war, which was part of the larger Bosnian War. During Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing Croat forces seized the television broadcasting stations (for example at Skradno) and created its own local radio and television to carry propaganda, seized the public institutions, raised the Croatian flag over public institution buildings, and imposed the Croatian Dinar as the unit of currency. During this time, Busovača's Bosniaks were forced to sign an act of allegiance to the Croat authorities, fell victim to numerous attacks on shops and businesses and, gradually, left the area out of fear that they would be the victims of mass crimes.[45] According to ICTY Trial Chambers in Blaškić case Croat authorities created a radio station in Kiseljak to broadcast nationalist propaganda.[46] A similar pattern was applied in Mostar and Gornji Vakuf (where Croats created a radio station called Radio Uskoplje).[47] Local propaganda efforts in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by the Croats, were supported by Croatian daily newspapers such as Večernji list and Croatian Radiotelevision, especially by controversial reporters Dijana Čuljak and Smiljko Šagolj who are still blamed by the families of Bosniak victims in Vranica case for inciting massacre of Bosnian POWs in Mostar, when broadcasting a report about alleged terrorists arrested by Croats who victimized Croat civilians. The bodies of Bosnian POWs were later found in Goranci mass grave. Croatian Radiotelevision presented Croat attack on Mostar, as a Bosnian Muslim attack on Croats in alliance with the Serbs. According to ICTY, in the early hours of May 9, 1993, the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) attacked Mostar using artillery, mortars, heavy weapons and small arms. The HVO controlled all roads leading into Mostar and international organisations were denied access. Radio Mostar announced that all Bosniaks should hang out a white flag from their windows. The HVO attack had been well prepared and planned.[48]

During the ICTY trials against Croat war leaders, many Croatian journalists participated as the defence witnesses trying to relativise war crimes committed by Croatian troops against non-Croat civilians (Bosniaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbs in Croatia). During the trial against general Tihomir Blaškić (later convicted of war crimes), Ivica Mlivončić, Croatian columnist in Slobodna Dalmacija, tried to defend general Blaškić presenting number of claims in his book Zločin s pečatom about alleged genocide against Croats (most of it unproven or false), which was considered by the Trial Chambers as irrelevant for the case. After the conviction, he continued to write in Slobodna Dalmacija against the ICTY presenting it as the court against Croats, with chauvinistic claims that the ICTY cannot be unbiassed because it is financed by Saudi Arabia (Muslims).[49][50]

See also

- Propaganda

- Bosnian War

- Kosovo War

- Milovan Drecun, journalist from Radio Television of Serbia in the 1990s

- Joint Criminal Enterprise

- Serbian war crimes in the Yugoslav Wars

References

- ^ Ratna instalacija: Falsifikat "Večernjih novosti" u ulju

- ^ frontline: the world's most wanted man: bosnia: how yugoslavia's destroyers harnessed the media, Public Broadcasting Service, 1998

- ^ Serbian state media begins to waver in its support of Milosevic, 05 October 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g h EXPERT REPORT OF RENAUD DE LA BROSSE "Political Propaganda and the Plan to Create 'A State For All Serbs:' Consequences of using media for ultra-nationalist ends" in five parts 1 2 3 4 5

- ^ Globalizing the Holocaust: A Jewish ‘useable past’ in Serbian Nationalism, by David MacDonald, University of Otago

- ^ Politika falsifikata, by Serbian newspaper VREME (Serbian)

- ^ http://www.un.org/icty/babic/trialc/judgement/index.htm

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (2005-04-26). "Balkan states yielding to Hague". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/25/world/europe/25iht-bosnia.html.

- ^ "Politika Falsifikata". http://www.vreme.com/arhiva_html/431/8.html#IVC.

- ^ "ICTY - Testimony dr.Vesna Bosanac". http://www.un.org/icty/milosevic/trialc/order-e/030117_2.htm#IVC.

- ^ Svjedok: Strugar je lagao da 30. 000 ustaša napada Boku

- ^ a b Reckoning: The 1991 Siege of Dubrovnik and the Consequences of the “War for Peace”

- ^ Attack on Dubrovnik: 30 000 Ustasa marsira na Crnu Goru ("Rat za mir" documentary)

- ^ Annex XI.A : The battle of Dubrovnik. United Nations Commission of Experts (28 December 1994). University of the West of England. Accessed 7 September 2009.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (August 10, 1997). "Serbian Media is One-Man Show". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A00EFDE133CF933A2575BC0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all#IVC.

- ^ "ICTY Serbian TV accuses Croats of burning tyres in Dubrovnik siege". http://www.un.org/icty/transe42/040303IT.htm#IVC.

- ^ ANATOMY+OF+A+BALKAN+FRAME-UP#IVC "ANATOMY OF A BALKAN FRAME-UP, Jerusalem Post". http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/jpost/access/99731976.html?dids=99731976:99731976&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=Feb+3%2C+1993&author=Batsheva+Tsur&pub=Jerusalem+Post&edition=&startpage=07&desc= ANATOMY+OF+A+BALKAN+FRAME-UP#IVC.

- ^ "Affairs In the Army". http://www.scc.rutgers.edu/serbian_digest/44/t44-1.htm#IVC.

- ^ Malic, Nebojsa (June 26, 2003). "The Serbian Lincoln? Yugoslavia, Secession and War". Antiwar.com. http://www.antiwar.com/malic/m062603.html. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "Milan Martic Transcript". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 17 August 2006. p. 6621. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/martic/trans/en/060817IT.htm. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Milan Martic Transcript". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 23 October 2006. p. 9913, 9914. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/martic/trans/en/061023IT.htm. Retrieved 25 September 2011. "Do you see that in fact he does not say, as you claimed, that the war wouldn't have happened had we didn't want it. He does not say that. In fact, what he says, sir, is that they wanted -- they wanted to achieve their goals through peace but that they were ready for war and that they would not give up their goals for an independent Croatia. But he does not say that: "The war would not have happened had we not wanted it."

- ^ "Lažni citati [Fake quotes"]. http://www.hrvatski-vojnik.hr/hrvatski-vojnik/3502011/domovinskirat.asp. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Al-Kai'da u Bosni i Hercegovini:Mit ili stvarna opasnost?

- ^ a b SENSE Tribunal:ICTY - WE FOUGHT WITH THE BH ARMY, BUT NOT UNDER ITS COMMAND [1]; 9 September 2007

- ^ a b "Predrag Matvejević analysis". http://www.islam.co.ba/razmisljanja/index.php?subaction=ostalo&id=1070747643.

- ^ According to the conclusion in Amir Kubura case

- ^ a b c "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - The media". http://www.un.org/icty/stakic/trialc/judgement/sta-tj030731e.htm#ID2di.

- ^ a b "ICTY: Duško Tadić judgement - Greater Serbia". http://www.un.org/icty/tadic/trialc2/judgement/tad-tj970507e.htm#_Toc387417236.

- ^ Voice of the Victims > Ivo Atlija

- ^ "ICTY: Stanislav Galić judgement". http://www.icty.org/x/cases/galic/acjug/en/gal-acjud061130.pdf.

- ^ "ICTY: Dragomir Milošević judgement". http://www.icty.org/x/cases/dragomir_milosevic/acjug/en/091112.pdf.

- ^ a b Fish, Jim. (February 5, 2004). Sarajevo massacre remembered. BBC.

- ^ Moore, Patrick. (August 29, 2005). Serbs Deny Involvement in Shelling. Omri Daily Digest.

- ^ ""Markale" granatirali muslimani u režiji Zapada [Muslims with the support of the West committed Markale Massacres]" (in Serbian). Glas Javnosti. 2007-12-18. http://www.glas-javnosti.rs/node/11198/print. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Galić verdict- 2. Sniping and Shelling of Civilians in Urban Bosnian Army-held Areas of Sarajevo [2]

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?gl=GB&hl=en-GB&v=LzUqQxNb8qw&e

- ^ http://www.crovid.com/televizija+srbije+rts+vidovnjaci+velika+srbija/2801/video

- ^ Yugoslav Army's Central Intelligence Unit: Clandestine Operations Foment War

- ^ Milosevic's Propaganda War, by Judith Armatta, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, February 27, 2003

- ^ ICTY indictment against Vojislav Seselj

- ^ BBC: Kosovo Picture File, The Media War

- ^ Nato targets Serb propaganda

- ^ Serbian Journalism after Communism & Milosevic

- ^ RTS Apology

- ^ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict — A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 - b) The municipality of Busovača". http://www.un.org/icty/blaskic/trialc1/judgement/bla-tj000303e-3.htm#IIIA1b.

- ^ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict — A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 - c) The municipality of Kiseljak". http://www.un.org/icty/blaskic/trialc1/judgement/bla-tj000303e-3.htm#IIIA1c.

- ^ "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict — IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - 2. The Conflict in Gornji Vakuf". http://www.un.org/icty/kordic/trialc/judgement/kor-tj010226e-5.htm#IVA2.

- ^ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict — Mostar attack". http://www.un.org/icty/naletilic/trialc/judgement/nal-tj030331-1.htm#IIB2.

- ^ Slobodna Dalmacija — NAJVEĆI DONATOR HAAŠKOG SUDA JE — SAUDIJSKA ARABIJA [3]

- ^ Igor Lasić — Izlog izdavačkog smeća

Sources

- EXPERT REPORT OF RENAUD DE LA BROSSE "Political Propaganda and the Plan to Create 'A State For All Serbs:' Consequences of using media for ultra-nationalist ends" in five parts 1 2 3 4 5

- BIRN Bosnian Institute, Analysis: Media Serving the War, Aida Alić, 20 July 2007

- Milosevic's Propaganda War, by Judith Armatta, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, February 27, 2003

- British Journalism Review, Too many truths, by Geoffrey Goodman, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1999

Categories:- History of Serbia

- Greater Serbian ideology

- Croatian War of Independence

- Bosnian War

- Kosovo War

- Yugoslav Wars

- Propaganda by country

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.