- Knoxville, Tennessee

-

City of Knoxville — City — The City of Knoxville, Tennessee

SealNickname(s): The Marble City,[1] Heart of the Valley,[2] Queen City of the Mountains,[3] K-Town[4] Location within the U.S. state of Tennessee. Coordinates: 35°58′22″N 83°56′32″W / 35.97278°N 83.94222°WCoordinates: 35°58′22″N 83°56′32″W / 35.97278°N 83.94222°W Country United States State Tennessee County Knox Settled 1786 Incorporated 1791 Government – Type Mayor-council government – Mayor Daniel Brown (acting) – Mayor-elect Madeline Rogero Area[5] – City 98.09 sq mi (254.0 km2) – Land 92.66 sq mi (240.0 km2) – Water 5.43 sq mi (14.1 km2) 5.5% Elevation[6] 886 ft (270 m) Population (2010)[7] – City 178,874 – Density 1,876.7/sq mi (724.6/km2) – Metro 699,247 – Combined Statistical Pop 1,029,155 – Demonym Knoxvillian

KnoxvilliteTime zone EST (UTC-5) – Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) Zip code 37901-37902, 37909, 37912, 37914-37924, 37927-37934, 37938-37940, 37950, 37995-37998 Area code(s) 865 FIPS code 47-40000[8] GNIS feature ID 1648562[9] Website www.cityofknoxville.org Founded in 1786, Knoxville is the third-largest city in the U.S. state of Tennessee, U.S.A., behind Memphis and Nashville, and is the county seat of Knox County.[10] It is the largest city in East Tennessee, and the second-largest city (behind Pittsburgh) in the Appalachia region. As of the 2000 United States Census, Knoxville had a population of 173,890;[7] the July 2007 estimated population was 183,546.[11] Knoxville is the principal city of the Knoxville Metropolitan Statistical Area with a metro population of 655,400, which is in turn the central component of the Knoxville-Sevierville-La Follette Combined Statistical Area with 1,029,155 residents.

Of Tennessee's four major cities, Knoxville is second oldest to Nashville, which was founded seven years earlier. After Tennessee's admission into the Union in 1796, Knoxville was the state's first capital, in which capacity it served until 1819, when the capital was moved to Murfreesboro, prior to Nashville receiving the designation. The city was named in honor of the first Secretary of War, Henry Knox.

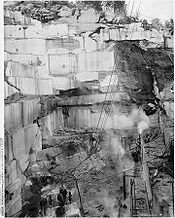

One of Knoxville's nicknames is The Marble City.[12] In the early 20th century, a number of quarries were active in the city, supplying Tennessee pink marble (actually Ordovician limestone of the Holston Formation) to much of the country. Notable buildings such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington are constructed of Knoxville marble. The National Gallery's fountains were turned by Candoro Marble Company, which once ran the largest marble lathes in the United States.

Knoxville was once also known as the Underwear Capital of the World.[13] In the 1930s, no fewer than 20 textile and clothing mills operated in Knoxville, and the industry was the city's largest employer. In the 1950s, the mills began to close, causing an overall population loss of 10% by 1960.

Knoxville is also the home of the University of Tennessee's flagship campus. The university's sports teams, called the "Volunteers" or "Vols", are extremely popular in the surrounding area. In recognition of this popularity, the telephone area code for Knox County and eight adjacent counties is 865 (VOL). Knoxville is also the home of the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame, almost entirely thanks to the popularity of Pat Summitt and the University of Tennessee women's basketball team.

Contents

History

Main article: History of Knoxville, TennesseeEarly history

The first humans to form substantial settlements in what is now Knoxville arrived during the Woodland period (c. 1000 B.C. – 1000 A.D).[14] One of the oldest man-made structures in Knoxville is a burial mound constructed during the early Mississippian period (c. 1000 A.D.). The mound is located on the University of Tennessee campus.[15] Other prehistoric sites include an Early Woodland habitation area at the confluence of the Tennessee River and Knob Creek (near the Knox-Blount county line),[14] and Dallas Phase Mississippian villages at Post Oak Island (also along the river near the Knox-Blount line),[16] and at Bussell Island (at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River near Lenoir City).[17]

By the 18th century, the Cherokee had become the dominant tribe in the East Tennessee region, although they were consistently at war with the Creeks and Shawnee.[18][19] The Cherokee people called the Knoxville area kuwanda'talun'yi, which means "Mulberry Place."[20] Most Cherokee habitation in the area was concentrated in the Overhill settlements along the Little Tennessee River, southwest of Knoxville.

The first Euro-American traders and explorers arrived in the Tennessee Valley in the late 17th century, although there is significant evidence that Hernando de Soto visited the Bussell Island site in 1540.[21] The first major recorded Euro-American presence in the Knoxville area was the Henry Timberlake expedition, which passed through the confluence of the Holston and French Broad into the Tennessee River in December 1761. Timberlake, who was en route to the Overhill settlements along the Little Tennessee River, recalled being pleasantly surprised by the deep waters of the Tennessee after having struggled down the relatively shallow Holston for several weeks.[22]

Settlement

The end of the French and Indian War and confusion brought about by the American Revolution led to a drastic increase in Euro-American settlement west of the Appalachians.[23] By the 1780s, Euro-American settlers were already established in the Holston and French Broad valleys. The U.S. Congress ordered all illegal settlers out of the valley in 1785, but with little success. As settlers continued to trickle into Cherokee lands, tensions between the settlers and the Cherokee rose steadily.[24]

In 1786, James White, a Revolutionary War officer, and his friend James Connor built White's Fort near the mouth of First Creek, on land White had purchased three years earlier.[25] In 1790, White's son-in-law, Charles McClung—who had arrived from Pennsylvania the previous year—surveyed White's holdings between First Creek and Second Creek for the establishment of a town. McClung drew up 64 0.5-acre (0.20 ha) lots. The waterfront was set aside for a town common. Two lots were set aside for a church and graveyard (First Presbyterian Church, founded 1792). Four lots were set aside for a school. That school was eventually chartered as Blount College and it served as the starting point for the University of Tennessee, which uses Blount College's founding date of 1794, as its own. Also in 1790, President George Washington appointed North Carolina surveyor William Blount governor of the newly-created Territory South of the River Ohio.

One of Blount's first tasks was to meet with the Cherokee and establish territorial boundaries and resolve the issue of illegal settlers.[26] This he accomplished almost immediately with the Treaty of Holston, which was negotiated and signed at White's Fort in 1791. Blount originally wanted to place the territorial capital at the confluence of the Clinch River and Tennessee River (now Kingston), but when the Cherokee refused to cede this land, Blount chose White's Fort, which McClung had surveyed the previous year. Blount named the new capital Knoxville after Revolutionary War general and Secretary of War Henry Knox, who at the time was Blount's immediate superior.[27]

Problems immediately arose from the Holston Treaty. Blount believed that he had "purchased" much of what is now East Tennessee when the treaty was signed in 1791. However, the terms of the treaty came under dispute, culminating in continued violence on both sides. When the government invited the Cherokee's chief Hanging Maw for negotiations in 1793, Knoxville settlers attacked the Cherokee against orders, killing the chief's wife. Peace was renegotiated in 1794.[28]

Antebellum Knoxville

Knoxville served as capital of the Territory South of the River Ohio and as capital of Tennessee (admitted as a state in 1796) until 1817,[25] when the capital was moved to Murfreesboro. Early Knoxville has been described as an "alternately quiet and rowdy river town."[29] Early issues of the Knoxville Gazette—the first newspaper published in Tennessee—are filled with accounts of murder, theft, and hostile Cherokee attacks. Abishai Thomas, a friend of William Blount, visited Knoxville in 1794 and wrote that while he was impressed by the town's modern frame buildings, the town had "seven taverns" and no church.[30]

Knoxville initially thrived as a way station for travelers and migrants heading west. Its situation at the confluence of three major rivers in the Tennessee Valley brought flatboat and later steamboat traffic to its waterfront in the first half of the 19th-century, and Knoxville quickly developed into a regional merchandising center. Local agricultural products—especially tobacco, corn, and whiskey—were traded for cotton, which was grown in the Deep South.[25] The population of Knoxville more than doubled in the 1850s with the arrival of the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad in 1855.[29]

Among the most prominent citizens of Knoxville during the Antebellum years was James White's son, Hugh Lawson White (1773–1840). White first served as a judge and state senator before being nominated by the state legislature to replace Andrew Jackson in the U.S. Senate in 1825. In 1836, White ran unsuccessfully for president, representing the Whig Party.[31]

The U.S. Civil War

Anti-slavery and anti-secession sentiment ran high in East Tennessee in the years leading up to the U.S. Civil War. William "Parson" Brownlow, the radical publisher of the Knoxville Whig, was one of the region's leading anti-secessionists (although he defended the practice of slavery).[32] Blount County, just south of Knoxville, had developed into a center of abolitionist activity, due in part to its relatively large Quaker faction and the anti-slavery president of Maryville College, Isaac Anderson.[33] The Greater Warner Tabernacle AME Zion Church, Knoxville was reportedly a station on the underground railroad.[34] Business interests, however, guided largely by Knoxville's trade connections with cotton-growing centers to the south, contributed to the development of a strong pro-secession movement within the city. The city's pro-secessionists included among their ranks Dr. J.G.M. Ramsey, a prominent historian whose father had built the Ramsey House in 1797. Thus, while East Tennessee and greater Knox County voted decisively against secession in 1861, the city of Knoxville favored secession by a 2-1 margin. In late May 1861, just before the secession vote, delegates of the East Tennessee Convention met at Temperance Hall in Knoxville in hopes of keeping Tennessee in the Union. After Tennessee voted to secede the following month, the convention met in Greeneville and attempted to create a separate Union-aligned state in East Tennessee.[35][36]

In July 1861, after Tennessee had joined the Confederacy, General Felix Zollicoffer arrived in Knoxville as commander of the District of East Tennessee. While initially lenient toward the city's Union sympathizers, Zollicoffer instituted martial law in November of that year after Union guerillas destroyed seven of the city's bridges. The command of the district passed briefly to George Crittenden and then to Kirby Smith, the latter of whom launched a failed invasion of Kentucky in August 1862. In early 1863, General Simon Buckner took command of Confederate forces in Knoxville. Anticipating a Union invasion, Buckner fortified Fort Loudon (in West Knoxville, not to be confused with the colonial fort to the southwest) and began constructing earthworks throughout the city. The approach of Union forces under Ambrose Burnside in the Summer of 1863, however, forced Buckner to evacuate Knoxville before the earthworks were completed.[37]

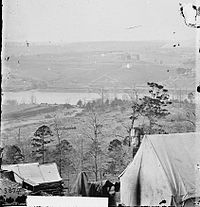

Burnside arrived in Knoxville in early September 1863. Like the Confederates, he immediately began fortifying the city. The Union forces rebuilt Fort Loudon and erected 12 other forts and batteries flanked by entrenchments around the city. Burnside moved a pontoon bridge upstream from Loudon, allowing Union forces to cross the river and build a series of forts along the heights of South Knoxville, including Fort Stanley and Fort Dickerson.[38]

As Burnside was fortifying Knoxville, the Confederate army defeated Union forces at the Battle of Chickamauga (near the Tennessee-Georgia line) and subsequently laid siege to Chattanooga. On November 3, 1863, the Confederates dispatched General James Longstreet north to attack Burnside at Knoxville. Longstreet initially wanted to attack the city from the south, but lacking the means to carry the necessary pontoon bridges, he was forced to cross the river further downstream at Loudon (November 14) and march against the city's heavily-fortified western section. On November 15, General Joseph Wheeler unsuccessfully attempted to dislodge Union forces in the heights of South Knoxville, and the following day Longstreet failed to cut off retreating Union forces at Campbell's Station (now Farragut). On November 18, General William P. Sanders was mortally wounded while conducting delaying maneuvers west of Knoxville, and Fort Loudon was renamed Fort Sanders in his honor. On November 29, after a two-week siege, the Confederates attacked Fort Sanders, but retreated after a fierce 20-minute engagement. On December 4, after word of the Confederate setback at Chattanooga reached Longstreet, Longstreet abandoned his attempts to take Knoxville and retreated into winter quarters at Russellville. He rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia the following Spring.[39]

Reconstruction and the Industrial Age

After the war, northern investors such as the brothers Joseph and David Richards helped Knoxville recover relatively quickly. Joseph and David Richards convinced 104 Welsh immigrant families to migrate from the Welsh Tract in Pennsylvania to work in a rolling mill then co-owned by John H. Jones. These Welsh families settled in an area now known as Mechanicsville.[citation needed] The Richards brothers also co-founded the Knoxville Iron Works beside the L&N Railroad, also employing Welsh workers. Later the site would be used as the grounds for the 1982 World's Fair.[citation needed]

Other companies that sprang up during this period were Knoxville Woolen Mills, Dixie Cement, and Woodruff's Furniture. Between 1880 and 1887, 97 factories were established in Knoxville, most of them specializing in textiles, food products, and iron products.[40] By the 1890s, Knoxville was home to more than 50 wholesaling houses, making it the third largest wholesaling center by volume in the South.[40] The Candoro Marble Works, established in the community of Vestal in 1914, became the nation's foremost producer of pink marble and one of the nation's largest marble importers.[41]

In 1869, Thomas Hughes, a Union-sympathizer and president of East Tennessee University, secured federal wartime restitution funding and state-designated Morrill Act funding to expand the college, which had been occupied by both armies during the war.[42] In 1879, the school changed its name to the University of Tennessee, hoping to secure more funding from the Tennessee state legislature. Charles Dabney, who became president of the university in 1887, overhauled the faculty and established a law school in an attempt to modernize the scope of the university.[42]

The post-war manufacturing boom brought thousands of immigrants to the city. The population of Knoxville grew from around 5,000 in 1860 to 32,637 in 1900. West Knoxville was annexed in 1897, and over 5,000 new homes were built between 1895 and 1904.[29]

In 1901, train robber Kid Curry (whose real name was Harvey Logan), a member of Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch was captured after shooting two deputies on Knoxville's Central Avenue. He escaped from the Knoxville Jail and rode away on a horse stolen from the sheriff.[citation needed]

The Progressive Era and the Great Depression

The growing city of Knoxville hosted the Appalachian Exposition in 1910 and again in 1911, and the National Conservation Exposition in 1913. The latter is sometimes credited with giving rise to the movement to create a national park in the Great Smoky Mountains, some 20 miles (32 km) south of Knoxville.[43] Around this time, a number of affluent Knoxvillians began purchasing summer cottages in Elkmont, and began to pursue the park idea more vigorously. They were led by Knoxville businessman Colonel David C. Chapman, who, as head of the Great Smoky Mountains Park Commission, was largely responsible for raising the funds for the purchase of the property that became the core of the park. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park opened in 1933.[44]

Knoxville's reliance on a manufacturing economy left it particularly vulnerable to the effects of the Great Depression. The Tennessee Valley also suffered from frequent flooding, and millions of acres of farmland had been ruined by soil erosion. To control flooding and improve the economy in the Tennessee Valley, the federal government created the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933. Beginning with Norris Dam, TVA constructed a series of hydroelectric and other power plants throughout the valley over the next few decades, bringing flood control, jobs, and electricity to the region.[45] The Federal Works Projects Administration, which also arrived in the 1930s, helped build McGhee-Tyson Airport and expand Neyland Stadium.[29] TVA's headquarters, which consists of two twin high rises built in the 1970s, were among Knoxville's first modern high-rise buildings.

In 1948, the soft drink Mountain Dew was first marketed in Knoxville, originally designed as a mixer for whiskey.[46] Around the same time, John Gunther, author of Inside USA, dubbed Knoxville the "ugliest city" in America. Gunther's description jolted the city into enacting a series of beautification measures that helped improve the appearance of the Downtown area.[43]

Modern Knoxville

Knoxville's textile and manufacturing industries largely fell victim to foreign competition in the 1950s and 1960s, and after the establishment of the Interstate Highway system in the 1960s, the railroad—which had been largely responsible for Knoxville's industrial growth—began to decline. The rise of suburban shopping malls in the 1970s drew retail revenues away from Knoxville's Downtown area. While government jobs and economic diversification prevented widespread unemployment in Knoxville, the city sought to recover the massive loss of revenue by attempting to annex neighboring communities in Knox County. These annexation attempts often turned combative, and several attempts to merge the Knoxville and Knox County governments failed though the school boards merged on 1 July 1987.[29]

With annexation attempts stalling, Knoxville initiated several projects aimed at boosting revenue in the Downtown area. The 1982 World's Fair—the most successful of these projects—became one of the most popular world's fairs in U.S. history with 11 million visitors. The fair's energy theme was selected due to Knoxville being the headquarters of the Tennessee Valley Authority and for the city's proximity to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The Sunsphere, a 266-foot (81 m) steel truss structure topped with a gold-colored glass sphere, was built for the fair and remains one of Knoxville's most prominent buildings,[47] along with the adjacent amphitheater which underwent a renovation that was completed in 2008.

Ever since, Knoxville's downtown has been developing, with the opening of the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame and the Knoxville Convention Center, redevelopment of Market Square, a new visitors center, a regional history museum, a Regal Cinemas theater, several restaurants and bars, and many new and redeveloped condominiums. Since 2000 Knoxville has successfully brought business back to the downtown area. The arts in particular have begun to flourish, there are multiple venues for outdoor concerts and Gay St. hosts a new arts annex and gallery surrounded by many studios and new business as well. The Tennessee and Bijou Theaters underwent renovation providing a good basis for the city and its developers to re purpose the old downtown and have had great success to date revitalizing this once great section of Tennessee.[citation needed]

Geography

Knoxville is located at 35°58′22″N 83°56′32″W / 35.97278°N 83.94222°W (35.972882, -83.942161)[48].

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 98.1 square miles (254 km2), of which, 92.7 square miles (240 km2) of it is land and 5.4 square miles (14 km2) of it is water. The total area is 5.5% water.[5]

In the southeast part of the city, the French Broad River (flowing from Asheville, North Carolina) joins the Holston River (flowing from Kingsport) to form the Tennessee River. Knoxville is centered around a hilly area along the north bank of the river between its First Creek and Second Creek tributaries. This area now comprises Downtown Knoxville. South Knoxville refers to the industrial and residential areas along the south bank of the river (extending to the Blount County line), and West Knoxville typically refers to the area beyond Sequoyah Hills, much of which is situated along Kingston Pike and the merged I-40 and I-75. The Knox County section of the Tennessee River is technically part of Fort Loudoun Lake, an impoundment of the river created by the completion of Fort Loudoun Dam (near Lenoir City) in 1940.

The hills and ridges surrounding Knoxville are part of the Appalachian Ridge-and-Valley Province, which consists of a series of elongate and narrow ridges that traverse the upper Tennessee Valley. The most substantial Ridge-and-Valley structures in the Knoxville area are Bays Mountain, which runs along the Knox-Blount county line to the south, and Beaver Ridge, which passes through the northern section of the town. The Great Smoky Mountains—a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains—are located approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of Knoxville.

Climate

Knoxville falls in the humid subtropical climate zone (Koppen climate classification Cfa), although it is not quite as hot as areas to the south and west due to the higher elevations. Summers are hot and humid, with July highs averaging 87 °F (31 °C), lows averaging 66 °F (19 °C), and an average of 29 days per year with temperatures above 90 °F (32 °C).[49] Winters are generally cool, with occasional small amounts of snow. January averages a high of around 45 °F (7 °C) and a low of around 25 °F (−4 °C), although low temperaures in the teens are not uncommon. Single digits are very rare, occurring once every few years. The record high for Knoxville is 104 °F (40 °C) occurring July 12, 1930, while the record low is −24 °F (−31 °C) occurring January 21, 1985.[50] Annual precipitation averages around 48 in (1,219 mm), and average winter snowfall is 11.5 inches (29 cm).

Climate data for Knoxville, Tennessee Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °F (°C) 77

(25)83

(28)88

(31)93

(34)96

(36)102

(39)104

(40)102

(39)103

(39)92

(33)84

(29)82

(28)104

(40)Average high °F (°C) 46.1

(7.8)51.3

(10.7)60.6

(15.9)69.3

(20.7)77.0

(25.0)84.1

(28.9)87.7

(30.9)87.0

(30.6)81.7

(27.6)70.9

(21.6)59.8

(15.4)49.9

(9.9)68.78

(20.44)Average low °F (°C) 26.2

(−3.2)28.4

(−2.0)36.2

(2.3)43.4

(6.3)53.2

(11.8)62.2

(16.8)66.9

(19.4)65.3

(18.5)58.6

(14.8)45.0

(7.2)36.4

(2.4)29.3

(−1.5)45.93

(7.74)Record low °F (°C) −24

(−31)−12

(−24)1

(−17)21

(−6)32

(0)42

(6)44

(7)48

(9)36

(2)23

(−5)5

(−15)−6

(−21)−24

(−31)Precipitation inches (mm) 5.30

(134.6)4.43

(112.5)5.66

(143.8)4.22

(107.2)4.98

(126.5)4.49

(114)4.91

(124.7)3.52

(89.4)3.25

(82.6)3.05

(77.5)4.43

(112.5)5.09

(129.3)53.33

(1,354.6)Snowfall inches (cm) 3.2

(8.1)2.7

(6.9)1.6

(4.1).2

(0.5)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0).4

(1)1.5

(3.8)9.6

(24.4)Avg. precipitation days 12.6 11.2 13.1 11.0 12.1 10.3 11.3 8.7 8.4 8.1 10.4 12.2 129.4 Sunshine hours 136.4 146.9 207.7 258.0 288.3 291.0 288.3 279.0 231.0 217.0 153.0 124.0 2,620.6 Source no. 1: [51] Source no. 2: [52] Knoxville Metropolitan Area

Knoxville is the central city in the Knoxville Metropolitan Area, an Office of Management and Budget (OMB)-designated metropolitan statistical area (MSA) that covers Knox, Anderson, Blount, Loudon, and Union counties. MSAs consist of a core urban center and the outlying communities and rural areas with which it maintains close economic ties. They are not administrative divisions, and should not be confused with "metropolitan government," or a consolidated city-county government, which Knoxville and Knox County lack.[53]

The Knoxville Metropolitan area includes unincorporated communities such as Halls, Powell, Karns, Corryton, Concord, and Mascot, which are located in Knox County outside of Knoxville's city limits. Along with Knoxville, major municipalities in the Knoxville Metropolitan Area include Alcoa, Maryville, Lenoir City, Loudon, Farragut, Oak Ridge, Clinton, and Maynardville. As of 2008, the population of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area was 691,152.[53]

Additionally, the Knoxville MSA is the chief component of the larger OMB-designated Knoxville-Sevierville-La Follette TN Combined Statistical Area (CSA). The CSA also includes the Morristown Metropolitan Statistical Area (Hamblen, Grainger, and Jefferson counties) and the Sevierville (Sevier County), La Follette (Campbell County), Harriman (Roane County), and Newport (Cocke County) Micropolitan Statistical Areas. Municipalities in the CSA, but not the Knoxville MSA, include Morristown, Rutledge, Dandridge, Jefferson City, Sevierville, Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, LaFollette, Jacksboro, Harriman, Kingston, Rockwood, and Newport. The combined population of the CSA as of the 2000 Census was 935,659. Its estimated 2008 population was 1,041,955.[53]

Georgia Tech researchers have mapped the Knoxville MSA as one of the 18 'Major Cities' in the Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion.[54]

Neighborhoods

- Arlington

- Bearden

- Bluegrass

- Burlington

- Cedar Bluff

- Chilhowee Park

- Colonial Village

- Dante

- Downtown

- East Knoxville

- Edgewood

- Emory Place

- Fairmont-Emoriland

- Farmington

- Five Points

- Forest Heights

- Fort Sanders, also called "the Fort"

- Fountain City

- Fourth & Gill

- Hardin Valley

- Holston Hills

- Island Home Park

- Kimberlin Heights

- Lake Forest

- Lindbergh Forest

- Lonsdale

- Mechanicsville

- Morningside

- Moshina Heights

- Mt. Vista

- North Hills

- North Knoxville

- Norwood

- Oakwood-Lincoln Park

- Old City

- Old North Knoxville

- Old Sevier

- Parkridge

- Pine Springs

- Rocky Hill

- Riverbend

- Sequoyah Hills

- South Haven

- South Knoxville

- Vestal

- Ward Town

- Wedgewood Hills

- West Hills

- West Knoxville

- Westwood

- Western Heights

- Westmoreland

- Wood Haven

Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1850 2,076 — 1870 8,682 — 1880 9,693 11.6% 1890 22,535 132.5% 1900 32,637 44.8% 1910 36,346 11.4% 1920 77,818 114.1% 1930 105,802 36.0% 1940 111,580 5.5% 1950 124,769 11.8% 1960 111,827 −10.4% 1970 174,587 56.1% 1980 175,045 0.3% 1990 165,121 −5.7% 2000 177,661 7.6% 2010 178,874 0.7% As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 177,661 people, 76,650 households, and 40,164 families residing in the city, and the Knoxville Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 616,079. The population density was 1,876.7 people per square mile (724.6/km²). There were 84,981 housing units at an average density of 917.1 per square mile (354.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 79.7% White, 16.2% African American, 1.45% Asian, 0.31% Native American, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.72% from other races, and 1.57% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.58% of the population.

There were 76,650 households out of which 22.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.3% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.6% were non-families. 38.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.12 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the city the population was spread out with 19.7% under the age of 18, 16.8% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 19.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females there were 90.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city is $27,492, and the median income for a family is $37,708. Males had a median income of $29,070 versus $22,593 for females. The per capita income for the city is $18,171. About 14.4% of families and 20.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.1% of those under age 18 and 12.0% of those age 65 or over.

In 2006, ERI published an analysis that identified Knoxville as the most affordable U.S. city for new college graduates, based on the ratio of typical salary to cost of living.[55]

Population and household growth are expected to follow employment growth, causing increased housing demand during the forecast period. Resident employment should continue to grow at a pace equal to that from 2000 to the Current date. As population continues to increase and the labor force grows, the unemployment rate is projected to increase slightly to 3.7 percent. The population growth is estimated to result in 12,900 new households in the HMA by the Forecast date. Demand for new housing for the period from April 1, 2005, to April 1, 2008, is estimated to total 13,100 units—10,400 sales units and 2,700 rental units.

Economy

Knoxville's economy is largely fueled by the regional location of the main campus of the University of Tennessee, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and other Department of Energy facilities in nearby Oak Ridge, the National Transportation Research Center, and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

In April 2008, Forbes Magazine named Knoxville among the Top 10 Metropolitan Hotspots in the United States[56] and within Forbes' Top 5 for Business & Careers, just behind cities like New York and Los Angeles.[57]

In March 2009, CNN ranked Knoxville as the 59th city in the top 100 US metro areas, in terms of real estate price depreciation.[58] The median price of a home in Knoxville is $184,900.[59]

Kiplinger has ranked Knoxville at #5 in its list of Best Value Cities 2011 citing "college sports, the Smoky Mountains and an entrepreneurial spirit."[60]

Major companies headquartered in Knoxville

- AC Entertainment, co-producers of the Bonnaroo Music Festival

- Brunswick Boat Group

- Bush Brothers and Company

- Cellular Sales, the nation's largest Verizon Wireless retailer

- DeRoyal Industries

- EdFinancial Services

- The H. T. Hackney Company, wholesale grocery distributor

- Jewelry Television, television network

- Petro's Chili & Chips

- Pilot Corporation and its truck stop subsidiary Pilot Flying J

- Regal Entertainment Group

- Sea Ray

- Scripps Networks Interactive, including HGTV

- Tennessee Valley Authority (a government corporation)

- Tombras Group, advertising agency

- Weigel's

Culture

Knoxville is home to a rich arts community and has many festivals throughout the year. Its contributions to old-time, bluegrass and country music are numerous, from Flatt & Scruggs and Homer & Jethro to the Everly Brothers. For the past several years an award-winning listener-funded radio station, WDVX[citation needed], has broadcast weekday lunchtime concerts of bluegrass music, old-time music and more from the Knoxville Visitor's Center on Gay Street, as well as streaming its music programming to the world over the Internet.[citation needed]

Knoxville also boasts an Opera Company which has been guided by Don Townsend for over two decades. The KOC performs a season of opera every year with a talented chorus as the backbone of each production.[citation needed]

In its May 2003 "20 Most Rock & Roll towns in the U.S." feature, Blender ranked Knoxville the 17th best music scene in the United States.[citation needed]In the ’90s, noted alternative-music critic Ann Powers, author of Weird Like Us: My Bohemian America, referred to the city as "Austin without the hype".[citation needed]

The city also hosts numerous art festivals, including the 17-day Dogwood Arts Festival in April, which features art shows, crafts fairs, food and live music. Also in April is the Rossini Festival, which celebrates opera and Italian culture. June's Kuumba (meaning creativity in Swahili) Festival commemorates the region's African American heritage and showcases visual arts, folk arts, dance, games, music, storytelling, theater, and food. Autumn on the Square showcases national and local artists in outdoor concert series at historic Market Square, which has been revitalized with specialty shops and residences. Every Labor Day brings Boomsday, the largest Labor Day fireworks display in the United States, to the banks of the Tennessee River between Neyland Stadium and downtown.[citation needed]

Events

- Big Ears Festival

- Boo At The Zoo

- Big KnoxVenture Race

- Boomsday

- Corvette Expo

- Dogwood Arts Festival

- Destination ImagiNation Global Finals

- Great Knoxville Rubber Duck Race

- GreekFest

- Hank Days

- Honda Hoot

- Knoxville Brewers' Jam

- Knoxville Lindy Exchange

- Feast With the Beasts @ Knoxville Zoo

- Fantasy of Trees

- Knoxville Marathon

- Knoxville Symphony Orchestra

- Kuumba Festival

- Market Square Farmers' Market Knoxville Market Square District Association

- NSRA Street Rod Nationals South

- Rossini Festival [61]

- Sevier Heights Living Christmas Tree The Living Christmas Tree

- Ska Weekend

- Sundown in the City

- Tennessee Valley Fair

- Vestival

Sites of interest

- Bijou Theatre

- Bleak House

- William Blount Mansion

- Fountain City Art Center

- Candoro Marble Works

- Civic Coliseum

- Fort Dickerson

- Haley Heritage Square

- Knoxville Botanical Gardens and Arboretum

- Knoxville Convention Center

- Knoxville Greenways

- Knoxville Museum of Art

- Knoxville Police Museum

- Knoxville Zoo

- Mabry-Hazen House

- Marble Springs

- Market Square

- Frank H. McClung Museum

- Museum of East Tennessee History

- National Register of Historic Places, Knox County, Tennessee

- Old City

- Ramsey House

- Sunsphere

- Tennessee Theatre

- Three Rivers Rambler Train Ride

- Volunteer Landing

- World's Fair Park

- James White's Fort

- Ijams Nature Center

- Tennessee River Boat

Media and popular culture

The Knoxville News Sentinel is the local daily newspaper in Knoxville, with a Sunday circulation of 150,147 (as of March 31, 2007), owned by the E. W. Scripps Company.[62] Metro Pulse is a standard weekly publication covering popular culture, arts, and entertainment, also owned by E.W. Scripps. The Knoxville Voice is a former populist alternative newspaper that was published on a biweekly basis from 2006-2009.[63]

The Knoxville metro area is served by many local television and radio stations. As of 2010[update], the Knoxville designated market area (DMA) is the 59th largest in the U.S. with 552,380 homes, according to Nielsen Market Research.[64] The major network television affiliates are WATE 6 (ABC), WMAK 7 (RTV), WVLT 8 (CBS), WBIR 10 (NBC), WBXX 20 (CW), WPXK 23 (Ion), and WTNZ 43 (Fox). WVLT, known on-air as VolunteerTV, also operates a MyNetworkTV channel on its digital subchannel. This channel was the area's UPN affiliate from 1995-2006. East Tennessee PBS operates Knoxville's Public Broadcasting Service station at WKOP 17. Knoxville is also the headquarters of Scripps Networks Interactive (subsidiary of E. W. Scripps), which operates several cable television networks, including HGTV, DIY Network, Food Network, Cooking Channel, Travel Channel and Great American Country.[65] Home shopping network, Jewelry Television, is also based in the city. There are also a wide variety of radio stations in the Knoxville area, catering to many different interests, including news, talk radio, and sports, as well as an eclectic mix of musical interests.

The 1999 film October Sky was filmed in Knoxville as well as several counties in east Tennessee,[66] and the 2000 film Road Trip was partially filmed at the University of Tennessee campus downtown.[67] The film Box of Moonlight, starring John Turturro and Sam Rockwell, was filmed and takes place in and around Knoxville.[68] The March 31, 1996 episode of The Simpsons, entitled Bart on the Road, features Bart and his friends renting a car and driving to Knoxville after finding a promotional brochure for the city's 1982 World's Fair, only to discover the fair has long ended, and its featured attraction, the Sunsphere, has fallen into decay.[69] Academy Award-winning director and producer, Quentin Tarantino was born in Knoxville, as well as actors Johnny Knoxville, David Keith, and Brad Renfro. Survivor: The Australian Outback finalist Tina Wesson is also from Knoxville.[70]

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and playwright James Agee was born in Knoxville and spent his early years there. His novel A Death in the Family centers around the Fort Sanders neighborhood where his family lived and chronicles the death of his father.[71] Another Pulitzer recipient, Cormac McCarthy, spent most of his childhood in Knoxville. His novel Suttree revolves around life among the city's working class in the early 1950s.[72]

Singer Ava Barber, famous for her tenure on The Lawrence Welk Show, was born and spent much of her early life in Knoxville.

Entertainer Dolly Parton, a native of Sevierville, received her first taste of fame in Knoxville, as a teenager, performing as a regular on Cas Walker's local radio show.

Other references to Knoxville in literature and music include:

- “Knoxville Courthouse Blues”, Hank Williams, Jr., 1984.

- "The Ballad of Thunder Road", Robert Mitchum, 1957. Lyrics reference Knoxville's Bearden community.

- "The Knoxville Girl", first recorded in 1924. traditional Appalachian ballad.

- "Knoxville: Summer of 1915", Samuel Barber, 1947 voice & orchestra piece based on 1938 short prose by James Agee.

- "Satan is Busy In Knoxville," song recorded in 1930 by jazz singer Leola Manning[73]

- "Smoky Mountain Rain", Ronnie Milsap, 1980. Lyrics begin “Thumbed my way from LA back to Knoxville . . ."

- "The Man in the Overstuffed Chair," a short story by playwright Tennessee Williams, gives a brief description of the death of Williams's father, Cornelius, at a Knoxville hospital, and his subsequent burial at Old Gray Cemetery.[74]

- Swiss travel writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach visited Knoxville in the 1930s, and wrote an essay about the city, "Auf der Schattenseite von Knoxville," which appeared in the December 1937 edition of the Swiss magazine, National Zeitung.[75]

- Pulitzer Prize-winning author Peter Taylor's last novel, In the Tennessee Country, makes numerous references to a "Knoxville cemetery" where the main character's grandfather (a fictitious politician) is buried. This is a possible allusion to Old Gray Cemetery, where Taylor's own grandfather, Governor Robert Love Taylor, was originally buried in 1912.[76]

- Twain, Mark. Life on the Mississippi, Chapter 40. Twain wrote about a gunfight in downtown Knoxville involving Joseph Mabry, Jr., owner of Knoxville’s antebellum Mabry-Hazen House.

- Part of the 1915 Anne W. Armstrong novel, The Seas of God, takes place in a fictional town called "Kingsville," which was based on Knoxville.[77]

- Van Ryan, Jane. The Seduction of Miss Evelyn Hazen. The book chronicles the sensational lawsuit between Knoxville socialite Evelyn Hazen, granddaughter of Joseph Mabry, Jr., and her fiancee.

- "What I Need to Do", Kenny Chesney, 1999. Lyrics include the line ". . . maybe head up north to Knoxville, Tennessee . . ."

- “Waitin’ on a Woman”, Brad Paisley, 2008. Lyrics reference Knoxville's West Town Mall.

- Woman In Hiding, a 1949 film noir starring actress Ida Lupino, has multiple scenes that take place in Knoxville.[78]

- In the short story "Just Another Perfect Day", by John Varley, aliens make it so that Knoxville never existed.[citation needed]

- Steve Earle refers to Knoxville in his 1988 song, "Copperhead Road" from the eponymous album and referenced it in Oxycontin Blues from his Washington Square Serenade album, 2007.

- The Felice Brothers refer to "fluttering a chinese fan in a "Knoxville Fashion" in their song Wonderful Life, from their Felice Brothers album (2008).

- Dire Straits guitarist Mark Knopfler recorded a song entitled, "Daddy's Gone to Knoxville," on his 2002 solo album, The Ragpicker's Dream.

Sports

- Knoxville Force (National Premier Soccer League, Southeast Division)

- Knoxville Ice Bears (Southern Professional Hockey League)

- Knoxville Rugby Club (Division II member of the South Territory, USA Rugby Union)

- Tennessee Smokies (Southern League, Double-A affiliate of the Chicago Cubs)

- Tennessee Volunteers – University of Tennessee Athletics

Government

Knoxville is governed by a mayor and nine-member City Council. It uses the strong-mayor form of the mayor-council system.[79] There are three council members who are elected at-large and six council members that represent individual districts. The City Council meets every other Tuesday at 7 p.m. in the Main Assembly Room of the City County Building.[80] As of January 10, 2011, the current mayor is Daniel T. Brown,[81] who replaced Bill Haslam. Haslam served from 2004 until January 2011, when he resigned to serve as the 49th Governor of Tennessee.[82] The previous mayor of sixteen years, Victor Ashe, was named United States Ambassador to Poland in June 2004. Ashe was term-limited and could not serve another term. On November 8, 2011, Madeline Rogero was elected to be the first female mayor of Knoxville.[83] She will be sworn in on December 17, 2011.

Education

Knoxville is home to the main campus of the University of Tennessee. It is also home to:

- Fountainhead College of Technology (formerly Tennessee Institute of Electronics)

- Johnson University (formerly Johnson Bible College)

- Knoxville College

- Pellissippi State Community College (formerly Pellissippi State Technical Community College)

- South College (formerly Knoxville Business College)

In addition, the following institutions have branch campuses in Knoxville:

- ITT Technical Institute

- King College

- Lincoln Memorial University

- National College of Business & Technology

- Roane State Community College

- Strayer University

- Tennessee Wesleyan College

- Tusculum College

Also, the distance education offeror Huntington College of Health Sciences has its offices in Knoxville.

The main library serving Knoxville is the Lawson McGhee Public Library, located in downtown Knoxville.

Transportation

Principal highways serving the city Interstate 40 to Asheville, North Carolina, and Nashville and Interstate 75 to Chattanooga and Lexington. Knoxville and the surrounding area is served by McGhee Tyson Airport. Public transportation is provided by KAT. Rail freight is offered by CSX and Norfolk Southern.

Major streets

- Alcoa Highway (US 129; TN 115)

- Asheville Highway (US 11E/US 25W/US 70; TN 9)

- Broadway (US 441;TN 33/TN 71)

- Central Street

- Chapman Highway (US 441;TN 33/TN 71)

- Clinton Highway (US 25W;TN 9)

- Cedar Bluff Road

- Cumberland Avenue, also known as "the Strip" (US 11/US 70; TN 1)

- Gay Street

- Gov. John Sevier Highway (TN 168)

- Hall of Fame Drive

- Henley Street (US 441;TN 33/TN 71)

- James White Parkway, formerly called the Business Loop or Downtown Loop (TN 158)

- Kingston Pike (US 11/US 70;TN 1)

- Magnolia Avenue (US 11/US 70;TN 1)

- Merchants Drive

- Middlebrook Pike (TN 169)

- Neyland Drive (TN 158)

- Northshore Drive

- Parkside Drive / North Peters Road

- Pellissippi Parkway (I-140 and TN 162)

- Rutledge Pike (US 11W;TN 1)

- Seventeenth Street

- South Central Street

- South Knoxville Connector

- Summit Hill Drive

- Washington Pike (TN 61)

- Western Avenue, formerly Asylum Street (TN 62)

Sister cities

Knoxville has seven sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International:[84]

Chełm, Poland

Chełm, Poland Chengdu, PR China

Chengdu, PR China Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Kaohsiung, Taiwan Larissa, Greece

Larissa, Greece Muroran, Japan

Muroran, Japan Neuquen, Argentina

Neuquen, Argentina Yesan County, South Korea

Yesan County, South Korea

See also

- List of people from Knoxville, Tennessee

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Knox County, Tennessee

References

- ^ Ask Doc Knox, "What's With All This Marble City Business?" Metro Pulse, 10 May 2010. Retrieved: 10 August 2011.

- ^ Lucile Deaderick, Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976).

- ^ Mark Banker, Appalachians All: East Tennessee and the Elusive History of an American Region (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2010), p. 83.

- ^ Jack Neely, From the Shadow Side: And Other Stories of Knoxville, Tennessee (Tellico Books, 2003).

- ^ a b "Census 2000 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Places". 2002-01-10. http://www.census.gov/tiger/tms/gazetteer/places2k.txt. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "Feature Detail Report for: City of Knoxville". USGS. 2008-03-10. http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/f?p=gnispq:3:::NO::P3_FID:2404842. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ a b "Knoxville (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. 2007-05-07. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/47/4740000.html. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. http://geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ US Census Bureau Factfinder

- ^ Jack Neely, The Marble City: A Photographic Tour of Knoxville's Graveyards (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), xxi.

- ^ Video: A Monument to underwear from Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ a b Fletcher Jolly III, "40KN37: An Early Woodland Habitation Site in Knox County, Tennessee", Tennessee Archaeologist 31, nos. 1–2 (1976), 51.

- ^ Frank H. McClung Museum, "Woodland Period." Retrieved: 25 March 2008.

- ^ James Strange, "An Unusual Late Prehistoric Pipe from Post Oak Island (40KN23)", Tennessee Archaeologist 30, no. 1 (1974), 80.

- ^ Richard Polhemus, The Toqua Site—40MR6, Vol. I (Norris, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1987), 1240-1246.

- ^ Cora Tula Watters, "Shawnee." The Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 278-279.

- ^ Ima Stephens, "Creek." The Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 252-253.

- ^ James Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee (Nashville: Charles Elder, 1972), 526.

- ^ Jefferson Chapman, Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History (Norris, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985), 97.

- ^ Henry Timberlake, Samuel Williams (ed.), Memoirs, 1756-1765 (Marietta, Georgia: Continental Book Co., 1948), 54.

- ^ William MacArthur, Knoxville, Crossroads of the New South (Tulsa, Okla.: Continental Heritage Press, 1982), 1-15.

- ^ Yong Kim, The Sevierville Hill Site: A Civil War Union Encampment on the Southern Heights of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Transportation Center, 1993), 9.

- ^ a b c Kim, The Sevierville Hill Site, 9.

- ^ MacArthur, 17.

- ^ William MacArthur, Jr., Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South (Tulsa, Oklahoma: Continental Heritage Press, 1982), 17-22.

- ^ G. H. Stueckrath, "Incidents in the Early Settlement of East Tennessee and Knoxville." Originally published in De Bow's Review Vol. XXVII (October 1859), O.S. Enlarged Series. Vol. II, No. 4, N.S. Pages 407-419. Transcribed for web content by Billie McNamara, 1999-2002. Retrieved: 25 February 2008.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e W. Bruce Wheeler, "Knoxville." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 28 February 2008.

- ^ MacArthur, Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South, 23.

- ^ Jonathan Atkins, "Hugh Lawson White." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 26 February 2008.

- ^ Forrest Conklin, "William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 27 February 2008.

- ^ Durwood Dunn, Cades Cove: The Life and Death of An Appalachian Community (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 125.

- ^ Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission, "Designated Properties: Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission." Retrieved: 27 February 2008.

- ^ MacArthur, Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South, 42-44.

- ^ Eric Lacy, Vanquished Volunteers: East Tennessee Sectionalism from Statehood to Secession (Johnson City, Tenn.: East Tennessee State University Press, 1965), pp. 217-233.

- ^ Kim, The Sevierville Hill Site, 10.

- ^ Kim, The Sevierville Hill Site, 10-12.

- ^ Kim, The Sevierville Hill Site, 15-17.

- ^ a b William Bruce Wheeler, "Knoxville, Tennessee." The Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 375.

- ^ Linda Snodgrass, "The Candoro Marble Works." 2000. Retrieved: 28 February 2008.

- ^ a b Milton Klein, "University of Tennessee." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 28 February 2008.

- ^ a b Jack Neely, "Knoxville, Tennessee." The Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 654.

- ^ Carlos Campbell, Birth of a National Park In the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969), 13-18, 32.

- ^ W. Bruce Wheeler, "Tennessee Valley Authority." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 28 February 2008.

- ^ http://www.mountaindew.com/about_dew/history/index.php[dead link]

- ^ W. Bruce Wheeler, "Knoxville World's Fair of 1982." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 28 February 2008.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ NOAA, Mean Number of Days With Maximum Temperature 90 Degrees F or Higher.

- ^ Knoxville Climate Page

- ^ "Climatography of the United States No. 20: KNOXVILLE EXP STN, TN 1971-2000.". [1]. http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/climatenormals/clim20/tn/404946.pdf. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ "Historical Weather for Knoxville, Tennessee, United States of America - Travel, Vacation and Reference Information". [2]. http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=062327&refer=&cityname=Knoxville-Tennessee-United-States-of-America. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas, U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ Georgia Institute of Technology :: CQGRD : Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion (PAM) Archived 27 September 2010 at WebCite

- ^ Economic Research Institute, Inc., ERI Economic Research Institute Releases Survey on Best and Worst Cities for College Grads – Based on salary/cost of living, Knoxville, TN rated best, press release, July 6, 2006

- ^ "Hot Spots - Forbes.com". Forbes. 7 April 2008. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090628104959/http://www.forbes.com/business/forbes/2008/0407/097.html.

- ^ Knoxville CBID

- ^ Top 100 Metro Area Home Price Forecast

- ^ Knoxville Real Estate Market Trends

- ^ Best Value Cities 2011:5. Knoxville, Tenn

- ^ Rossini | Knoxville Opera

- ^ Bryant, Ray; Hartmann, Bruce. "Knoxville News-Sentinel: Newspaper Publisher's Statement". Knoxville News-Sentinel. http://web.knoxnews.com/about/ABCPubStatement3-31-07.pdf. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "RIP, Knoxville Voice.". Metro Pulse. January 6, 2009. http://www.metropulse.com/news/2009/jan/06/rip-knoxville-voice/. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Local Television Market Universe Estimates: Comparisons of 2008-09 and 2009-10 Market Ranks.". Nielsen Media Research. http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/2009-2010-dma-ranks.pdf. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "About Scripps Networks.". Scripps Networks Interactive. http://www.scrippsnetworks.com/about.aspx?code=about. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Morrow, Terry (September 20, 2010). "'October Sky' cast & crew reunite in Oliver Springs.". Knoxville News-Sentinel. http://blogs.knoxnews.com/telebuddy/archives/2010/09/october-sky-cas.shtml. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Road Trip (2000).". IMDB. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0215129/. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Box of Moon Light (1996) - IMDb

- ^ "The Simpson's: "Bart on the Road" Episode.". Knoxville News-Sentinel. May 31, 1996. http://web.knoxnews.com/advertising/worldsfair/simpsons.html. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Famous Knoxvillians.". City of Knoxville. http://www.ci.knoxville.tn.us/about/famous.asp. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Life in a Small Southern Town.". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/americancollection/death/ei_town.html. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Todd, Raymond. "Suttree (1979).". www.cormacmccarthy.com. http://www.cormacmccarthy.com/works/suttree.htm. Retrieved April 1, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Lynn Point Records, The St. James Sessions. Retrieved: 5 February 2010.

- ^ Tennessee Williams, "The Man In the Overstuffed Chair." Collected Stories (New York: New Directions Books, 1985), p. xvi.

- ^ Jack Neely, From the Shadow Side: And Other Stories of Knoxville, Tennessee (Tellico Books, 2003), p. 24.

- ^ Jack Neely, Knoxville's Secret History (Scruffy Books, 1995), pp. 56-7.

- ^ M. Thomas Inge, Charles Reagan Wilson, et al., The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Literature (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), p. 174.

- ^ Neely, From the Shadow Side, p. 96.

- ^ Barker, Scott (August 19, 2002). "Council lets mayor keep gavel - for now". The Knoxville News-Sentinel.

- ^ "City Council". City of Knoxville. http://www.cityofknoxville.org/citycouncil/default.asp. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ^ "Biography of Mayor Daniel T. Brown". City of Knoxville. http://www.ci.knoxville.tn.us/mayor/bio.asp. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Schelzig, Erik (January 15, 2011). "GOP's Bill Haslam sworn in as Tenn. governor". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/15/AR2011011502403.html. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ http://blogs.knoxnews.com/humphrey/2011/11/madeline-rogero-elected-knoxvi.html

- ^ "Sister City Directory.". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. http://www.sister-cities.org/directory/index.cfm. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

Sources

- Barber, John W., and Howe, Henry. All the Western States and Territories, . . . (Cincinnati, Ohio: Howe's Subscription Book Concern, 1867). pp. 631–632.

- Carey, Ruth. "Change Comes to Knoxville." in These Are Our Voices: The Story of Oak Ridge 1942-1970, edited by James Overholt, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, 1987.

- Deaderick, Lucile, ed. Heart of the Valley—A History of Knoxville, Tennessee Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976.

- Jennifer Long; "Government Job Creation Programs-Lessons from the 1930s and 1940s" Journal of Economic Issues . Volume: 33. Issue: 4. 1999. pp 903+, a case study of Knoxville.

- Isenhour, Judith Clayton. Knoxville, A Pictorial History. (Donning Company, 1978, 1980).

- "Knoxville". The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/imagegallery.php?EntryID=K017. Retrieved 2006-03-14.

- McDonald, Michael, and Bruce Wheeler. Knoxville, Tennessee: Continuity and Change in an Appalachian City University of Tennessee Press, 1983. the standard academic history

- McKenzie, Robert Tracy. Lincolnites and Rebels: A Divided Town in the American Civil War (2009) on Knoxville excerpt and text search

- The Future of Knoxville's Past: Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville, Tennessee. (Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission, October, 2006).

- Rothrock, Mary U., editor. The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee. (Knox County Historical Committee; East Tennessee Historical Society, 1946).

- Temple, Oliver P. East Tennessee and the Civil War (1899) 588pp online edition

External links

- City of Knoxville (official web site)

- Knoxville Tourism and Sports Corporation

- Knoxville Business District

- Knoxville Historic District

- Knoxville travel guide from Wikitravel

- Knoxville at the Open Directory Project

- "Knoxville". Tennessee History for Kids. http://www.tnhistoryforkids.org/cities/knoxville. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- "Knoxville History". http://www.city-data.com/us-cities/The-South/Knoxville-History.html. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- The McClung museum at The University of Tennessee Knoxville, "Archaeology & the Native Peoples of Tennessee" exhibit. "Exhibit Link". http://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/newpermanent/archaeology/index.html.

Municipalities and communities of Knox County, Tennessee City Knoxville

Town Unincorporated

communitiesConcord | Corryton | Halls Crossroads | Karns | Mascot | New Hopewell | Powell | Solway | Strawberry Plains‡

Footnotes ‡This populated place also has portions in an adjacent county or counties

Neighborhoods of Knoxville, Tennessee Neighborhoods Bearden · Chilhowee Park · Colonial Village · Forest Heights · Fort Sanders · Fountain City · Fourth and Gill · Island Home Park · Lake Forest · Lindbergh Forest · Lonsdale · Mechanicsville · North Hills · Norwood · Oakwood-Lincoln Park · Old City · Old North Knoxville · Parkridge · Sequoyah Hills · South Knoxville · West Hills

Mayors of cities with populations exceeding 100,000 in Tennessee - A C Wharton

(Memphis)

- Daniel Brown (acting)

(Knoxville)

- Johnny Piper

(Clarksville)

- Tommy Bragg

(Murfreesboro)

Other states: AL • AK • AZ • AR • CA • CO • CT • DE • FL • GA • HI • ID • IL • IN • IA • KS • KY • LA • ME • MD • MA • MI • MN • MS • MO • MT • NE • NV • NH • NJ • NM • NY • NC • ND • OH • OK • OR • PA • RI • SC • SD • TN • TX • UT • VT • VA • WA • WV • WI • WYCategories:

Other states: AL • AK • AZ • AR • CA • CO • CT • DE • FL • GA • HI • ID • IL • IN • IA • KS • KY • LA • ME • MD • MA • MI • MN • MS • MO • MT • NE • NV • NH • NJ • NM • NY • NC • ND • OH • OK • OR • PA • RI • SC • SD • TN • TX • UT • VT • VA • WA • WV • WI • WYCategories:- Cities in Tennessee

- County seats in Tennessee

- Former United States state capitals

- Knoxville metropolitan area

- Knoxville, Tennessee

- Populated places established in 1786

- Populated places in Knox County, Tennessee

- State of Franklin

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.