- Clarksville, Tennessee

-

Clarksville, Tennessee — City — Clarksville's historic downtown Nickname(s): Queen of the Cumberland[1]

Gateway to the New South[2]

Tennessee's Top Spot[3]Location in Montgomery County and the state of Tennessee Coordinates: 36°31′47″N 87°21′33″W / 36.52972°N 87.35917°W Country United States State Tennessee County Montgomery Founded: 1785 Incorporated: 1808 Government - Mayor Kim McMillan Area - Total 95.5 sq mi (247.4 km2) - Land 94.9 sq mi (245.7 km2) - Water 0.7 sq mi (1.8 km2) Elevation 509 ft (155 m) Population (U.S. Census Bureau) - Total 123,564 Time zone CST (UTC-6) - Summer (DST) CDT (UTC-5) ZIP codes 37040-37044 Area code(s) 931 FIPS code 47-15160[4] GNIS feature ID 1269467[5] Website http://www.cityofclarksville.com/ Clarksville is a city in and the county seat of Montgomery County, Tennessee, United States,[6] and the fifth largest city in the state. The population was 132,929 in 2010 United States Census. Clarksville is the ninth fastest growing city in the nation and the principal central city of the Clarksville, TN-KY metropolitan statistical area, which consists of Montgomery County, Stewart County, Tennessee, Christian County, Kentucky, Trigg County, Kentucky and is the 10th fastest growing Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) in the nation.

The city was incorporated in 1785, making it Tennessee's first incorporated city, and named for General George Rogers Clark, frontier fighter and Revolutionary War hero,[2] brother of William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[7]

Clarksville is one of the south's most historic cities and the home of Austin Peay State University; The Leaf-Chronicle, the oldest newspaper in Tennessee; and neighbor to the Fort Campbell, United States Army base. Fort Campbell is the home of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), and is located approximately 10 miles (16 km) from downtown Clarksville, straddling the Tennessee-Kentucky state line. It is officially Fort Campbell, Kentucky due to the fact the base U.S. Post Office is on the Kentucky side of the base; the majority of Fort Campbell is within the state of Tennessee.

Contents

The city's nicknames

- Tennessee's Top Spot- was introduced as a new city "brand" and official nickname in April 2008.[8]

- The Queen City

- Clarksvegas

- Queen of the Cumberland

- Gateway to the New South[2]

Geography

Clarksville is located at 36°31′47″N 87°21′33″W / 36.52972°N 87.35917°W (36.5297222, -87.3594444)[9]. The elevation is 382 feet (116 m) above sea level. This altitude can be found on a section of Riverside Drive, which runs along the eastern bank of the Cumberland, but most of the city is higher. Clarksville's civil airport, Outlaw Field, is listed as 550 feet (170 m) AMSL by survey. According to Topo USA mapping software, the city square sits at 475 feet (145 m) and the courthouse at 509 feet (155 m). There is a point on the northern side of Memorial Drive near Medical Court that reaches 598 feet (182 m).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 95.5 square miles (247 km2), of which, 94.9 square miles (246 km2) of it is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) of it (0.71%) is water.

Clarksville is located on the northwest edge of the Highland Rim, which surrounds the Nashville Basin, and is 45 miles (72 km) northwest of Nashville.

Clarksville was founded on the Cumberland River near the confluence of the Cumberland and the Red River. The Cumberland flows downstream from Nashville, some 40 miles (64 km) southeast of Clarksville. From its beginnings, the river was the city's commercial lifeline. Flat boats and, by the 1820s, steamboats carried cotton, oats, soybeans and tobacco, downstream to the Ohio River and up the Ohio to Pittsburgh. More frequently, cargo went down the Ohio to the Mississippi River and New Orleans. Both dark-fired and burley tobacco are grown in the area, and European tobacco buyers helped make Clarksville the largest market in the world for dark-fired tobacco, particularly Type 22, used in smokeless products. It was considered to have the highest nicotine content of all tobaccos in the 19th century.

To the northwest of Clarksville, lies the Fort Campbell Military Reservation, home of the 101st Airborne Division. Much of Clarksville's economy can be attributed to Fort Campbell's presence (and Austin Peay State University). Most of Fort Campbell is in Tennessee, mostly in Montgomery and Stewart counties. Its post office is in Kentucky.

Fort Campbell North is a Census-designated place(CDP) in Christian County, Kentucky, United States. It contains most of the housing for the Fort Campbell Army base. The population was 14,338 at the 2000 census.

Fort Campbell North is part of the Clarksville, TN–KY Metropolitan Statistical Area

Major roads and highways

- U.S. Highway 41 Alternate (Madison Street and Fort Campbell Boulevard)

- U.S. Highway 79 (Wilma Rudolph Boulevard)

- Interstate 24 (designated a control city along route)

- State Route 12 (Ashland City Highway)

- State Route 13

- State Route 48

- State Route 76 ("Martin Luther King Jr. Parkway")

- State Route 374 (Warfield Blvd., 101st Airborne Division Parkway, Purple Heart Parkway)

ZIP codes

The ZIP codes used in the Clarksville area are: 37010, 37040, 37041, 37042, 37043, 37044, 37191.

Area code

Clarksville and the majority of Montgomery County use the area code 931, but a portion of eastern Montgomery County has use of the area code 615. Its Neighbor, Fort Campbell, uses area code 270.

Climate

Climate data for Clarksville, Tennessee Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °F (°C) 80

(27)82

(28)87

(31)92

(33)95

(35)108

(42)110

(43)107

(42)106

(41)97

(36)86

(30)80

(27)110

(43)Average high °F (°C) 45

(7)51

(11)61

(16)71

(22)79

(26)86

(30)90

(32)89

(32)83

(28)72

(22)60

(16)49

(9)69.7 Daily mean °F (°C) 35

(2)40

(4)49

(9)58

(14)66

(19)75

(24)79

(26)77

(25)71

(22)59

(15)48

(9)39

(4)58 Average low °F (°C) 25

(−4)29

(−2)36

(2)44

(7)54

(12)63

(17)68

(20)65

(18)58

(14)45

(7)36

(2)29

(−2)46 Record low °F (°C) −17

(−27)−11

(−24)0

(−18)22

(−6)32

(0)42

(6)47

(8)44

(7)32

(0)20

(−7)−2

(−19)−12

(−24)−17

(−27)Precipitation inches (mm) 4.10

(104.1)4.20

(106.7)5.41

(137.4)4.26

(108.2)5.01

(127.3)4.43

(112.5)4.28

(108.7)3.33

(84.6)3.76

(95.5)3.25

(82.6)4.60

(116.8)5.15

(130.8)51.78

(1,315.2)Snowfall inches (cm) 3.42

(8.69)2.51

(6.38)0.94

(2.39)0.07

(0.18)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0.04

(0.1)0.29

(0.74)1.36

(3.45)8.63

(21.92)Source: [10] Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1870 3,200 — 1880 3,880 21.3% 1890 7,924 104.2% 1900 9,431 19.0% 1910 8,548 −9.4% 1920 8,110 −5.1% 1930 9,242 14.0% 1940 11,831 28.0% 1950 16,246 37.3% 1960 22,021 35.5% 1970 31,719 44.0% 1980 49,327 55.5% 1990 70,315 42.5% 2000 103,455 47.1% Est. 2009 124,565 20.4% As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 103,455 people, 36,969 households, and 26,950 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,090.6 people per square mile (421.1/km²). There were 40,041 housing units at an average density of 422.1 per square mile (163.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 67.91% White, 23.23% African American, 0.54% Native American, 2.16% Asian, 0.25% Pacific Islander, 2.61% from other races, and 3.30% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.03% of the population. The census recorded 5,187 foreign-born residents in Clarksville.

There were 36,969 households out of which 41.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.4% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.1% were non-families. 21.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.12.

In the city the population was spread out with 28.8% under the age of 18, 13.6% from 18 to 24, 34.7% from 25 to 44, 15.6% from 45 to 64, and 7.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 100.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,548, and the median income for a family was $41,421. Males had a median income of $29,480 versus $22,549 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,686. About 8.4% of families and 10.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.8% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those age 65 or over.

History

Pre-Colonization and Native American History

The area now known as Tennessee was first settled by Paleo-Indians nearly 11,000 years ago. The names of the cultural groups that inhabited the area between first settlement and the time of European contact are unknown, but several distinct cultural phases have been named by archaeologists, including Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian whose chiefdoms were the cultural predecessors of the Muscogee people who inhabited the Tennessee River Valley prior to Cherokee migration into the river's headwaters.[11]

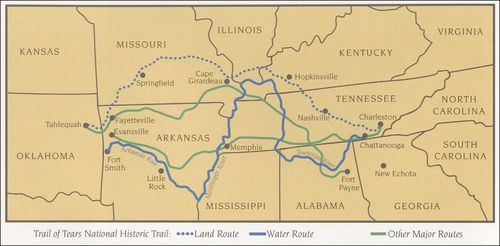

When Spanish explorers first visited Tennessee, led by Hernando de Soto in 1539–43, it was inhabited by tribes of Muscogee and Yuchi people. Possibly because of European diseases devastating the Native tribes, which would have left a population vacuum, and also from expanding European settlement in the north, the Cherokee moved south from the area now called Virginia. As European colonists spread into the area, the native populations were forcibly displaced to the south and west, including all Muscogee and Yuchi peoples, the Chickasaw, and Choctaw. From 1838 to 1839, nearly 17,000 Cherokees were forced to march from "emigration depots" in Eastern Tennessee, such as Fort Cass, to Indian Territory west of Arkansas. This came to be known as the Trail of Tears, as an estimated 4,000 Cherokees died along the way.[12]

Colonization

The Transylvania Purchase, bought from the Cherokee tribe, stretches from Sycamore Shoals in Elizabethton, Tennessee to the Wilderness Road into Kentucky.

The Transylvania Purchase, bought from the Cherokee tribe, stretches from Sycamore Shoals in Elizabethton, Tennessee to the Wilderness Road into Kentucky.

The area around Clarksville was first surveyed by Thomas Hutchins in 1768.He identified Red Paint Hill, a rock bluff at the confluence of the Cumberland and Red Rivers, as a navigational landmark.[13]

In the years between 1771 and 1775, John Montgomery, the namesake of the county, along with Kasper Mansker visited the area while on a hunting expedition. That same year in 1771, James Robertson led a group of some twelve or thirteen families involved with the Regulator movement from near where present day Raleigh, North Carolina now stands. In 1772, Robertson and the pioneers who had settled in Northeast Tennessee (along the Watauga River, the Doe River, the Holston River, and the Nolichucky River met at Sycamore Shoals to establish an independent regional government known as the Watauga Association. However, in 1772, surveyors placed the land officially within the domain of the Cherokee tribe, who required negotiation of a lease with the settlers. Tragedy struck as the lease was being celebrated, when a Cherokee warrior was murdered by a white man. Through diplomacy, Robertson made peace with the Cherokees, who threatened to expel the settlers by force if necessary.[14]

In March 1775, land speculator and North Carolina judge Richard Henderson met with more than 1,200 Cherokees at Sycamore Shoals, including Cherokee leaders such as Attacullaculla, Oconostota, and Dragging Canoe. In the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals (also known as the Treaty of Watauga), Henderson purchased all the land lying between the Cumberland River, the Cumberland Mountains, and the Kentucky River, and situated south of the Ohio River in what is known as the Transylvania Purchase from the Cherokee Indians. The land thus delineated, 20 million acres (81000 km?), encompassed an area half as large as the present state of Kentucky. Henderson's purchase was in violation of North Carolina and Virginia law, as well as the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited private purchase of American Indian land. Henderson may have mistakenly believed that a newer British legal opinion had made such land purchases legal.[15]

All of present day Tennessee was once recognized as one single North Carolina county: Washington County, North Carolina. Created in 1777 from the western areas of Burke and Wilkes Counties, North Carolina, Washington County had as a precursor a Washington District of 1775-76, which was the first political entity named for the Commander-in-Chief of American forces in the Revolution.[14][16]

Founding

In 1779, James Robertson brought a group of settlers from upper East Tennessee via Daniel Boone's "Wilderness Road". Robertson would later build an iron plantation in Cumberland Furnace.[citation needed] A year later, in 1780, John Donelson led a group of flat boats up the Cumberland River bound for the French trading settlement, French Lick (or Big Lick), that would later be Nashville. When the boats reached Red Paint Hill, Moses Renfroe, Joseph Renfroe, and Solomon Turpin, along with their families, branched off onto the Red River. They traveled to the mouth of Parson's Creek, near Port Royal, and came ashore to settle down.[citation needed] However, an attack by Indians in the summer drove them back. (See Port Royal State Park)

Clarksville was designated as a town to be settled in part by soldiers from the disbanded Continental Army that served under General George Washington during the American Revolutionary War.[citation needed] At the end of the war, the federal government lacked sufficient funds to repay the soldiers, so the Legislature of North Carolina , in 1790, designated the lands to the west of the state line as federal lands that could be used in the land grant program. Since the area of Clarksville had been surveyed and sectioned into plots, it was identified as a territory deemed ready for settlement. The land was available to be settled by the families of eligible soldiers as repayment of service to their country.

The development and culture of Clarksville has had an ongoing interdependence between the citizens of Clarksville and the military. The formation of the city is associated with the end of the American Revolutionary War.[citation needed] During the American Civil War a large percent of the male population was depleted due to Union Army victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Many Clarksville men were interned at Union prisoner of war (POW) camps. Clarksville also lost many native sons during World War I (WWI). With the formation of Camp Campbell, later Fort Campbell, during World War II (WWII), the bonds of military influence were strengthened. Soldiers from Fort Campbell, Kentucky have deployed in every military campaign since the formation of the post.[citation needed]

On January 16, 1784, John Armstrong filed notice with the Legislature of North Carolina to create the town of Clarksville, named after General George Rogers Clark.[citation needed] Even before it was officially designated a town, lots had been sold. In October of 1785, Col. Robert Weakley laid off the town of Clarksville for Martin Armstrong and Col. Montgomery, and Weakley had the choice of lots for his services. He selected Lot #20 at the northeast corner of Spring and Main Streets. The town consisted of 20 'squares' of 140 lots and 44 out lots. The original Court House was on Lot #93, on the north side of Franklin Street between Front and Second Street. The Public Spring was on Lot #74, on the northeast corner of Spring and Commerce Streets. Weakley built the first cabin there in January of 1786, and about February or March, Col. Montgomery came there and had a cabin built, which was the second house in Clarksville. After an official survey by James Sanders[disambiguation needed

], Clarksville was founded by the North Carolina Legislature on December 29, 1785. It was the second town to be founded in the area. Armstrong's layout for the town consisted of 12 four-acre (16,000 m²) squares built on the hill overlooking the Cumberland as to protect against floods.[citation needed] The primary streets (from north to south) that went east-west were named Jefferson, Washington (now College Street), Franklin, Main, and Commerce streets. North-south streets (from the river eastward) were named Water (now Riverside Drive), Spring, First, Second, and Third streets.

], Clarksville was founded by the North Carolina Legislature on December 29, 1785. It was the second town to be founded in the area. Armstrong's layout for the town consisted of 12 four-acre (16,000 m²) squares built on the hill overlooking the Cumberland as to protect against floods.[citation needed] The primary streets (from north to south) that went east-west were named Jefferson, Washington (now College Street), Franklin, Main, and Commerce streets. North-south streets (from the river eastward) were named Water (now Riverside Drive), Spring, First, Second, and Third streets.The tobacco trade in the area was growing larger every year and in 1789, Montgomery and Martin Armstrong persuaded lawmakers to designate Clarksville as an inspection point for tobacco.[citation needed] In 1790, Isacc Rowe Peterson staked a claim to Dunbar Cave, just northeast of downtown.

When Tennessee was founded as a state on June 1, 1796, the area around Clarksville and to the east was named Tennessee County. (This county was established in 1788, by North Carolina.) Later, Tennessee County would be broken up into modern day Montgomery and Robertson Counties, named to honor the men who first opened up the region for settlement.

The 19th Century

As time progressed into the 19th century, Clarksville grew at a rapid pace. By 1806, the town realized the need for an educational institution, and the Rural Academy was established that year. Later, the Rural Academy would be replaced by the Mount Pleasant Academy. By 1819, the newly-established town had 22 stores, including a bakery and silversmith. In 1820, steamboats begin to navigate the Cumberland, bringing hardware, coffee, sugar, fabric, and glass.[citation needed] They also exported flour, tobacco, cotton, and corn to ports like New Orleans and Pittsburgh along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Trade via land also grew as four main dirt roads were established, two to Nashville, one crossing the Red River via ferry called the Kentucky Road, and Russellville Road.[citation needed] In 1829, the first bridge connecting Clarksville to New Providence was built over the Red River. Nine years later, the Clarksville-Hopkinsville Turnpike was built. In 1855, Clarksville was incorporated as a city. Railroad service came to the town on October 1, 1859 in the form of the Memphis, Clarksville and Louisville Railroad. The line would later connect with other railroads at Paris, Tennessee and Guthrie, Kentucky.

Civil War Years

By the start of the Civil War, the combined population of the city and the county was 20,000. The area was openly for slavery, as blacks worked in the tobacco fields. In 1861, both Clarksville and Montgomery County voted unanimously to join the Confederate States of America.[citation needed] The proximity of the birthplace of Confederate President Jefferson Davis gave the city a strong tie to the CSA, and both sides saw the city as strategic and important. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston set up a defense line around Clarksville expecting a land attack; however, the Union sent troops and gunboats down the Cumberland, and in 1862, captured Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, and Clarksville. Between 1862 and 1865, the city would shift hands, but the Union would retain control of Clarksville to include control of the city's newspaper - The Leaf Chronicle for three years. Many slaves that had been freed gathered in Clarksville and joined the Union Army, which created all-black regiments. The remaining lived along the side of the river in shanties.

Clarksville is home to three Confederate States of America Army camps:

- Camp Boone located on U.S. Highway 79 Guthrie Road/(Wilma Rudolph Boulevard),

- Camp Burnet

- Fort Defiance, Tennessee, a Civil War outpost that overlooks the Cumberland river and Red river and was occupied by both Confederate and Union soldiers. Work is ongoing at the site to build an interpretive/ museum center to chronicle the local chapter in the Civil War.

On February 17, 1862, the USS Cairo along with another Union Ironclad came to Clarksville, TN and captured the city. There were no Confederate soldiers to contend with because they had left prior to the arrival of the ships. There were white flags flying over Ft. Defiance and over Ft. Clark. The citizens of the town that could get away, left as well. Before they left, Confederate soldiers tried to burn the railroad bridge that crossed the Cumberland River. The fire didn’t take hold and was put out before it could destroy the bridge. This railroad bridge made Clarksville very important to the Union. The USS Cairo tied up in Clarksville a couple of days before moving on to participate in the capture of Nashville.

Reconstruction

After the war, the city began Reconstruction, and in 1872, the existing railroad was purchased by the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. The city reached a high point until the Great Fire of 1878, which destroyed 15 acres (60,000 m²) of downtown Clarksville's business district, including the courthouse at that time and many other historic buildings. It was believed to have started in a Franklin Street store.[citation needed] After the fire, the city rebuilt and entered the 20th century with a fresh start.[citation needed] It was at this time that the first automobile rolled into town, drawing much excitement.[citation needed]

The 20th century

Another new form of entertainment soon came. In 1913, the Lillian Theater, Clarksville's first "movie house" for motion pictures, was opened on Franklin Street by Joseph Goldberg. It sat more than 500 people. Less than two years later, in 1915, the theater burned down. It was rebuilt later that year.[citation needed]

As World War I raged in Europe, many locals volunteered to go, reaffirming Tennessee as the Volunteer State, a nickname earned during the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War and other earlier conflicts. Also during this time, women's suffrage was becoming a major issue, and Clarksville women saw a need for banking independent of their husbands and fathers who were fighting. In response, the First Women's Bank of Tennessee was established in 1919 by Mrs. Frank J. Runyon.

The 1920s brought additional growth to the city. Travelwise, a bus line between Clarksville and Hopkinsville was established in 1922. 1927 saw the creation of Austin Peay Normal School, later to become Austin Peay State University. Two more theaters were added, the Majestic (with 600 seats) and the Capitol (with 900 seats) Theaters, both in 1928. John Outlaw, a local aviator, established Outlaw Field in 1929.

The largest change to the city came in 1942, as construction of Camp Campbell (now known as Fort Campbell) began. The new army base ten miles (16 km) northwest of the city, and capable of holding 23,000 troops, gave an immediate boost to the population and economy of Clarksville.

In recent decades, the size of Clarksville has doubled. Communities such as New Providence and Saint Bethlehem were annexed into the city, adding to the overall population. The creation of Interstate 24 north of Saint Bethlehem made the area prime for development, and today much of the growth along U.S. Highway 79 is commercial retail. In 1954, the Clarksville Memorial Hospital was founded along Madison Street. Downtown, the Lillian was renamed the Roxy Theater, and today it still hosts plays and performances weekly. Clarksville is currently one of the fastest growing large cities in Tennessee. At its present rate of growth, the city is on track to replace Chattanooga as the fourth largest city in Tennessee by 2020.

The Roxy has been used as a backdrop for numerous photo shoots, films, documentaries, music videos and television commercials;[citation needed] most notably for Sheryl Crow's Grammy-award winning song All I Wanna Do, which was shot in front of the Roxy in downtown Clarksville.[citation needed]

The Monkees 1966 classic #1 song Last Train to Clarksville was supposedly inspired by the city's train depot and about a soldier from Fort Campbell during the Vietnam War era, wanting to see his girlfriend one more time before deployment, fearing he may never come back home. Parts of Clarksville are also briefly seen in the songs Music video.

1999 Tornado

On the morning of January 22, 1999, the downtown area of Clarksville was devastated by an F3 tornado, damaging many buildings including the county courthouse. The tornado, 880 yards (800 m) wide, continued on a 4.3-mile (6.9 km)-long path that took it up to Saint Bethlehem. No one was seriously injured or killed in the destruction. Clarksville has since recovered, and has rebuilt much of the damage as a symbol of the city's resilience. Where one building on Franklin Street once stood has been replaced with a large mural of the historic buildings of Clarksville on the side of one that remained.

2010 Flood

On Sunday, May 2, 2010 Clarksville and a majority of central Tennessee to include Nashville and 22 counties in total, suffered expansive and devastating floods near the levels of the great flood of 1937. Many business along Riverside Drive along the Cumberland River were totally lost. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_2010_Tennessee_floods

History of the county courthouse

The first Montgomery County courthouse was built from logs in 1796 by James Adams. It sat close to the riverbank on the corner of what is now present-day Riverside Drive and Washington Street. It was later replaced by a second courthouse built in 1805, and a third in 1806, with the land provided by Henry Small. The fourth courthouse was built in 1811, and the first to be built of brick. It was constructed on the east half of Public Square, with the land donated by Martin Armstrong. In 1843, yet another courthouse was built, this time on Franklin Street. It would remain standing until the Great Fire of 1878.

The sixth and current courthouse was built between Second and Third Streets, with the cornerstone laid on May 16, 1879. This particular building was designed by George W. Bunting of Indianapolis, Indiana. Five years later, the downtown area was hit by a tornado, which damaged the roof of the courthouse. The building was rebuilt. On March 12, 1900, the building was again ravaged by fire, with the upper floors gutted and the clock tower destroyed. Many citizens wanted the courthouse torn down and replaced with a safer one, but the judge refused and repaired the damage.

The courthouse was destroyed once again by the January 22, 1999 tornado. The building of another new courthouse was on the minds of locals, but in the end the courthouse was fully restored as a county office building. On the fourth anniversary of the disaster the courthouse was rededicated. In addition to the restoration of the original courthouse and plazas, a new courts center was built on its north side.

Notable Clarksvillians

The following notable people were born in or have lived in Clarksville:

- Roy Acuff, country music star

- James E. Bailey (United States Senator from Tennessee)

- David Bibb (Current Acting Administrator of the General Services Administration (GSA))

- Willie Blount Governor of Tennessee 1809-1815

- Jimi Hendrix, Guitarist, singer and songwriter.

- Little Richard American singer, songwriter, pianist and recording artist

- Robert Burt, African-American surgeon

- Ben Clark (2nd youngest American to climb Mount Everest)

- Philander Claxton (Professor, United States Commissioner of Education, and APSU President)

- James Storm (Professional wrestler)

- Mageina Tovah (Actress best known for her roles as Glynis Figliola in the television series Joan of Arcadia and as Ursula Ditkovich in the Spider-Man films)

- Nate Colbert, MLB player

- Gretchen Cordy (Reality television cast member on "Survivor: Borneo" and local radio DJ)

- Mike Hondembroke, British-born social commentator and philanthropist

- Riley Darnell, former Tennessee State Senator and former Tennessee Secretary of State

- Harry Galbreath (American football player with Miami Dolphins, Green Bay Packers, and New York Jets)

- Brock Gillespie (Professional Basketball Player)

- Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer, writer under the pen-name Dorothy Dix, journalist who was famous for authoring a newspaper advice column

- Jeff Gooch, former NFL player, Tampa Bay Buccaneers '96-'01,'04 Detroit Lions'02-'03

- Ernest William Goodpasture (American pathologist and physician)

- Caroline Gordon (Novelist and wife of Allen Tate)

- Trenton Hassell (NBA athlete, Minnesota Timberwolves, Chicago Bulls, Dallas Mavericks, and New Jersey Nets)

- Roland Hayes (Musician)

- Tommy Head (Member of Tennessee House of Representatives)

- Richard J. Herrell Musician/producer, known for his work with Hippiedigger & Murk-a-Troid

- Gustavus Adolphus Henry Sr. (1804–1880), Whig/Kentucky and Democrat/Tennessee, known as the "Eagle Orator of Tennessee"

- Percy Howard, wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys

- Douglas S. Jackson, Tennessee State Senator

- Cave Johnson, Democrat, U.S. Congressman from Tennessee, and United States Postmaster General under James K. Polk from 1845–1849

- Howard Johnson (American football) (1916–1945) Football player, U.S. Marine - died on Iwo Jima

- Micah Johnson Miami Dolphins linebacker

- Dorothy Jordan (Drama actor)

- Otis Key, player and coach with the Harlem Globetrotters

- Joseph Buckner Killebrew (Educator, Lawyer, Innovator, originator of the liberal public school law of Tennessee)

- Rosalind Kurita (Member of Tennessee State Senate)

- Horace Lisenbee (MLB Player, Pitcher for Washington Senators American League Baseball Team)

- Horace Harmon Lurton, Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States

- John Hartwell Marable (Member of United States House of Representatives)

- Shawn Marion (NBA and Olympian athlete Phoenix Suns, Miami Heat, Toronto Raptors and Dallas Mavericks)

- Isaac Murphy, first Reconstruction Governor of Arkansas

- Robert Loftin Newman (Renowned oil painter)

- Mary C. Noble, Justice, Kentucky Supreme Court

- Wayne Pace (CFO of Time Warner)

- Asahel Huntington Patch, or A. H. Patch (Inventor of the Blackhawk corn sheller)

- Austin Peay (Tennessee governor from 1922 to 1927 and namesake to university)

- Chonda Pierce, Christian comedian and performer

- Key Pittman (United States Senator from Nevada)

- Jeff Purvis, Former (Nascar race car driver)

- Mark Day, Former (Nascar race car driver)

- James B. Reynolds (Member of United States House of Representatives)

- Mason Rudolph (Professional golfer) (no relation to Wilma Rudolph)

- Wilma Rudolph (First female athlete to win three Olympic Gold Medals in a single games)

- Brenda Vineyard Runyon (Founder and Director of a historic bank 1919-1926, First Womans Bank of Tennessee)

- Clarence Saunders, founder of the Piggly Wiggly supermarket business

- Evelyn Scott, poet and novelist

- Valentine Sevier, Revolutionary War soldier, and brother of John Sevier, Tennessee's first governor. (Built Sevier Station in Clarksville, a small fort for settlers to take refuge during attacks by the Native American Indians; this structure still stands today as a historic site.)

- George Sherrill, baseball player for the Los Angeles Dodgers

- Gregory D. Smith, first president of Tennessee Municipal Judges Conference

- Rachel Smith, Miss USA 2007

- Travis Stephens, football player with Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Chad Sugg Singer/Songwriter (Backseat Goodbye)

- Pat Summitt, UT Women's Basketball coach

- Frank Sutton, actor who played Sgt. Carter in television series Gomer Pyle, USMC

- Allen Tate, poet

- Sloan Thomas, former wide receiver for the Tennessee Titans

- Robert Penn Warren, poet

- Jamie Walker, relief pitcher for the Baltimore Orioles who formerly played for Kansas City Royals and Detroit Tigers

- Bubba Wells, APSU alumnus and former NBA player

- William Westmoreland, military commander in Vietnam

- William "Sammy" Stuard Chairman, Tennessee Banker's Association. CEO, F&M Bank

- Clarence Cameron White, musician

- James "Fly" Williams, basketball player in the original American Basketball Association in the 1970s

- Howie Wright, basketball player for the New York Knicks in the 1970s[17]

- Buck Young, actor who played Sergeant Whipple in the Gomer Pyle TV series

- Blake Widner and Allison Barnes, 2004 Wimbledon Mixed Doubles Champions

Education

Colleges and universities

- Austin Peay State University

- Bethel College

- Miller-Motte Technical College

- Nashville State Community College

- Daymar Institute

- Austins Beauty College

- North Central Institute

- North Tennessee Bible Institute

- Queen City College [1]

- Tennessee Technology Center

K-12

Clarksville Academy

Public schools

The Clarksville-Montgomery County School System operates a total of 36 public schools to serve about 30,000 students, including seven high schools, seven middle schools, 20 elementary schools, one magnet school for K-5, and the Middle College @ Austin Peay State University.

Public high schools (grades 9-12) in Clarksville-Montgomery County:

- Northeast High School (800 students)

- Clarksville High School (1,259 students)

- Rossview High School (1,500 students)

- Northwest High School (1,171 students)

- Kenwood High School (1,152 students)

- West Creek High School (1,000 students)

- Montgomery Central High School (950 students)

Public elementary schools in Clarksville-Montgomery County:

- Barkers Mill Elementary School (~1,110 students) - "Favorite Public School" (The Leaf-Chronicle's 2010 Readers Choice Awards, 2011 Readers Choice Awards)

- Barksdale

- Burt

- Byrns Darden

- Cumberland Heights

- East Montgomery

- Liberty

- Minglewood

- Moore Magnet

- Norman Smith

- Ringgold

- Rossview

- St. Bethlehem

- Woodlawn

- West Creek

Biggest public primary/middle schools in Clarksville-Montgomery County:

- Northeast Middle School (Students: 800; Grades: 6 - 8)

- Kenwood Middle School (Students: 750; Grades: 6 - 8)

- Richview Middle School (Students: 1,076; Grades: 6 - 8)

- Glenellen Elementary School (Students: 1,058; Grades: KG - 5)

- New Providence Middle School (Students: 1,027; Grades: 6 - 8)

- Rossview Middle School (Students: 996; Grades: 6 - 8)

- Sango Elementary School (Students: 941; Grades: KG - 5)

- Northeast Elementary School (Students: 933; Grades: KG - 5)

- Hazelwood Elementary School (Students: 913; Grades: KG - 5)

- Barkers Mill Elementary School (Students: 1,110; Grades KG - 5)

- Kenwood Elementary School (Students: 799; Grades: KG - 5)

- Montgomery Central Middle School (Students: ?; Grades: 6 - 8) (Cunningham, Tennessee)

- West Creek Middle School (Students: 1000; Grades: 6-8)

- Montgomery Central Elementary School (Students: 400; Grades: KG - 5) (Cunningham, Tennessee)

Private schools

Private high schools in Clarksville-Montgomery County:

- Clarksville Academy (Students: 613; ST; Grades: PK - 12)

- Montgomery Christian Academy (Students: 175; Grades: PK - 12)

- Bible Baptist Academy (Students: 142; Grades: PK - 12) (closed 2000)

- Weems Academy (Students: 58; Grades: 4 - 12)

- Academy for Academic Excellence (Students: 50; Grades: 1 - 12)

- Helicon/Clarksville Diagnostic (Students: 25; Grades: 6 - 12)

- Clarksville Christian School (Students: 156; Grades K-10)

Private primary/middle schools in Clarksville:

- St. Mary's Catholic School (Students 140; Grades K - 8)

- Immaculate Conception Preschool (Students: 156; Grades: PK - KG)

- Apostolic Christian School (Students: 17; Grades: PK - 9)

- Little Scholars (Montessori Method, Students 22; Ages 2.5-7)

Economy

Major industrial employers in Clarksville include:

- American Standard

- Averitt Hardwoods International

- Bridgestone Metalpha USA

- Convergys Corporation- Clarksville's second largest private employer

- Clarksville Foundry

- Florim USA

- Fort Campbell- Clarksville's largest employer

- Hemlock Semiconductor LLC (HSC)

- Hendrickson Trailer Suspensions Systems

- Jostens, Printing and Publishing Division

- Letica Corporation

- Precision Printing & Packaging

- Premiumwear, Inc.

- Print Xcel

- Quebecor

- Robert Bosch Corporation

- Smithfield Manufacturing, Inc

- SPX Corporation, Metal Forge Division

- Startek USA

- Trane- Clarksville's largest private employer

- UCAR Carbon Corporation

- Vulcan Corporation, Rubber Division

- Whitson Lumber Company

Other notable local companies include:

- F&M Bank

- Legends Bank

Airports

Clarksville is served commercially by Nashville International Airport but also has a small airport, Outlaw Field, located 10 miles (16 km) north of downtown. Outlaw Field accommodates nearly 40,000 private and corporate flights a year, and is also home to a pilot training school and a few small aircraft companies. It has two asphalt runways, one 6,000 feet (1800 m) by 100 feet (30 m) and the other 4,004 feet (1200 m) by 100 feet (30 m). Outlaw Field has received a $35,000 grant. The terminal is under renovation.

Cobb Field is a small private Airport. It is 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the Dover crossings area. just across the street from Liberty elementary. It has 1 runway grass/sod runway that measures at 1,752 ft (534 m). This airport is not open to the public.

Recognitions

In the June 2004 issue of Money, Clarksville was listed as one of the top five cities with a population of under 250,000 that would attract creative class jobs over the next 10 years.[18]

The city has also received good rankings in various categories in:

- Southern Business & Development Magazine (One of The South's Top 10 Places with Plenty of Talented Labor, May 2006)[citation needed]

- Forbes Magazine (90th Best City for Business and Careers, May 2001)[citation needed]

- Entrepreneur Magazine (No. 1 small city in the South)[citation needed]

- Money (57th Best Place to Live, July 1996)[citation needed]

- Golf Digest (America's 11th Best City for Public Golf, July 1998)[citation needed]

- Reader's Digest (38th Family-Friendly City, April 1997)[citation needed]

- National Civic League (a 2002 All America City Finalist)[citation needed]

Others can be located at the city's website.

Points of interest

- Downtown Artist Co-Op Also known as the DAC.

- Roxy Theatre (located downtown Clarksville)

- Governor's Square Mall

- Clarksville City Arboretum

- Clarksville Speedway

- Beachaven Vineyards & Winery

- Ringgold Mill (located in North Clarksville)

- Port Royal State Park (historic community site and location of one of the oldest points of European civilization in Montgomery County)

- Historic Collinsville (Historic village restored to illustrate the living conditions of early European and African American settlers)

- Customs House Museum and Cultural Center (located in downtown Clarksville, second largest general museum in Tennessee)

- L & N Train Station Restored downtown train station.

- Wilma Rudolph Statue (To honor one of America's most outstanding Olympic athletes and her legacy)

- Cumberland RiverWalk

- Dunbar Cave

- King's Bluff Rock climbing located along (Cumberland River) with over 200 routes

- Clarksville Public Square

- Alter Gallery

- Pillar of Cloud, Pillar of Fire (Sculpture by Gregg Schlanger located in Public Square)

- Enoch Tanner Wickham Statues located in nearby Palmyra, Tennessee

References

- ^ Queen City Lodge #761 - Free & Accepted Masons, accessed October 11, 2008

- ^ a b c Clarksville, Tennessee: Gateway to the New South, Fort Campbell website, accessed October 11, 2008

- ^ "Clarksville unveils new "Brand" as "Tennessee’s Top Spot!"". http://www.clarksvilleonline.com/2008/04/12/clarksville-unveils-new-brand-as-tennessees-top-spot/.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. http://geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Miller, Larry L. (2001). Tennessee place-names. Indiana University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780253339843. http://books.google.com/books?id=gQ-r54p36cgC&lpg=PR3&pg=PR3.

- ^ Clarksville unveils new “Brand” as “Tennessee’s Top Spot!”, Turner McCullough Jr., Clarksville Online, April 12, 2008

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Weather.com, Clarksville TN Averages and Records". Weather.com. http://www.weather.com/weather/wxclimatology/monthly/37043. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ "Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee." University of Tennessee, Frank H. McClung Museum. Retrieved: 5 December 2007.

- ^ Satz, Ronald. Tennessee's Indian Peoples. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1979. ISBN 0-87049-285-3

- ^ Christian G. Fritz, American Sovereigns: The People and America's Constitutional Tradition Before the Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2008) at p. 55-60 [ISBN 978-0-521-88188-3

- ^ a b http://www.tcarden.com/tree/ensor/Watag.html "Watauga Petition". Ensor Family Pages.

- ^ Boone: A Biography, Robert Morgan, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, 2008, ISBN 978-1-56512-615-2

- ^ http://www.jcedb.org/history/lostco.php "Lost Counties of Tennessee.

- ^ Howie Wright Statistics - Basketball-Reference.com

- ^ Clarksville, Tennessee. Money Mag Ranking.

External links

- Clarksville TN Real Estate Search

- City of Clarksville official site

- Clarksville Online newspaper

- The Leaf-Chronicle newspaper

- Clarksville, Tennessee at the Open Directory Project

- Clarksville Montgomery County School System

- City Data website

- Tennessee Historical Society

Coordinates: 36°31′47″N 87°21′34″W / 36.5297222°N 87.3594444°W

Municipalities and communities of Montgomery County, Tennessee City Clarksville

Unincorporated

communitiesCunningham | Oakridge | Palmyra | Port Royal | Saint Bethlehem | Sango | Southaven | Southside | Woodlawn

Military base Mayors of cities with populations exceeding 100,000 in Tennessee - A C Wharton

(Memphis)

- Daniel Brown (acting)

(Knoxville)

- Johnny Piper

(Clarksville)

- Tommy Bragg

(Murfreesboro)

Other states: AL • AK • AZ • AR • CA • CO • CT • DE • FL • GA • HI • ID • IL • IN • IA • KS • KY • LA • ME • MD • MA • MI • MN • MS • MO • MT • NE • NV • NH • NJ • NM • NY • NC • ND • OH • OK • OR • PA • RI • SC • SD • TN • TX • UT • VT • VA • WA • WV • WI • WYCategories:

Other states: AL • AK • AZ • AR • CA • CO • CT • DE • FL • GA • HI • ID • IL • IN • IA • KS • KY • LA • ME • MD • MA • MI • MN • MS • MO • MT • NE • NV • NH • NJ • NM • NY • NC • ND • OH • OK • OR • PA • RI • SC • SD • TN • TX • UT • VT • VA • WA • WV • WI • WYCategories:- Cities in Tennessee

- Populated places in Montgomery County, Tennessee

- County seats in Tennessee

- Populated places established in 1785

- Clarksville metropolitan area

- Clarksville, Tennessee

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.