- Marie Antoinette

-

Marie Antoinette of Austria

Marie Antoinette à la Rose, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1783) Queen of France and Navarre Tenure 10 May 1774 – 21 September 1792 Spouse Louis XVI of France Issue Marie Thérèse, Duchess of Angoulême

Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France

Louis XVII

Princess SophieFull name Maria Antonia Josephina Johanna House House of Habsburg-Lorraine Father Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor Mother Empress Maria Theresa Born 2 November 1755

Hofburg Palace, Vienna, AustriaDied 16 October 1793 (aged 37)

Place de la Révolution, Paris, FranceBurial 21 January 1815

Saint Denis Basilica, FranceSignature

Marie Antoinette (

/məˈriː æntwəˈnɛt/ or /æntwɑːˈnɛt/; French pronunciation: [maʁi ɑ̃twanɛt]; baptised Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna (or Maria Antonia Josephina Johanna[1]); 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I.

/məˈriː æntwəˈnɛt/ or /æntwɑːˈnɛt/; French pronunciation: [maʁi ɑ̃twanɛt]; baptised Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna (or Maria Antonia Josephina Johanna[1]); 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I.In April 1770, on the day of her marriage to Louis-Auguste, Dauphin of France, she subsequently became Dauphine of France. Marie Antoinette assumed the title of Queen of France and of Navarre when her husband, Louis XVI of France, ascended the throne upon the death of Louis XV in May 1774. After seven years of marriage, she gave birth to a daughter, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, the first of four children.

Initially charmed by her personality and beauty, the French people generally came to dislike her, accusing "the Austrian" of being profligate and promiscuous,[2] and of harboring sympathies for France's enemies, particularly Austria, since Marie Antoinette was, after all, Austrian.[3]

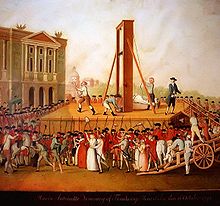

At the height of the French Revolution, Louis XVI was deposed and the monarchy abolished on 10 August 1792; the royal family was subsequently imprisoned at the Temple Prison. Nine months after her husband's execution, Marie Antoinette was herself tried, convicted of treason, and executed by guillotine on 16 October 1793.

Even after her death, Marie Antoinette is often considered to be a part of popular culture and a major historical figure,[4] being the subject of several books, films and other forms of media. Some academics and scholars have deemed her frivolous and superficial, and have attributed the start of the French Revolution to her; however, others have claimed that she was treated unjustly and that views of her ought be more sympathetic.[5][6][7]

Contents

Early life

Maria Antonia of Austria was born on 2 November 1755 at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria; on the next day, she was baptised Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna (also known as Maria Antonia Josephina Johanna[1]). She was the youngest daughter of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria Theresa, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, and ruler of the Habsburg dominions; her godparents were the King of Portugal and his wife.[8] In her family, she was simply called Antonia. Described at her birth as "a small, but completely healthy Archduchess",[9] she was also known at the Austrian court as Antonia, but more often as Madame Antoine, since French was commonly spoken in the Hofburg.[10] After all, Viennese society itself was multilingual, with many able to speak German, French, Italian and/or Spanish.

The relaxed ambience of court life in the Hofburg, where it was possible to often deviate from protocol,[11] was compounded by the private life which was developed by the Habsburgs even before Maria Antonia was born. In their private life, the family dressed in bourgeois attire, played games with non-royal children (they were, in fact, encouraged to play with such 'common' children by their parents), and were treated to gardens and menageries. She later attempted to recreate this atmosphere through her renovation of the Petit Trianon in France.

Maria Antonia had a simple and carefree childhood, especially in comparison to that of Louis XVI.[10] She was never lonely, since she never had the chance to be alone.[10] This was particularly evident in her relationship with her older sister, Maria Carolina: they were the two youngest girls, and shared the same governesses, first Countess Brandeis, then Countess Lerchenfeld, until 1767; Carolina once described her sister as someone she "loved extraordinarily".[12]

The Imperial family was one that thoroughly enjoyed music. Antonia herself learned to play the harpsichord, spinet and clavichord, as well as the harp, taught by Gluck.[10] During the family's musical evenings, she would sing French songs and Italian arias.[13] She also excelled at dancing – an accomplishment often remarked by those who saw her, whether friendly or hostile, having been carefully trained in it since her early youth.[14] She had an "exquisite" poise and a famously graceful deportment;[14] Horace Walpole once quoted Virgil as to her gait, saying, "vera incessu patuit dea" (she was in truth revealed to be a goddess by her step). She also loved dolls as a young girl, as captured by a family portrait in which seven-year-old Antonia excitedly held up a fancy doll.[14] Numerous dolls arrived at the Hofburg as soon as Marie Antoinette turned 13, wearing miniature versions of the ball gowns, afternoon dresses, and gold-trimmed gowns proposed for her.[14]

Antonia's education was poor, or at least it lacked the rigorous in training as Louis XVI's; her handwriting, for instance, was sprawling and careless in form.[10] It was not so much the teachers themselves, though, that made her education sub-par, but rather her lack of willingness to contribute intellectually to her lessons. Often, her tutors would finish the work themselves, out of fear of losing their positions. Under the guidance of Gluck, she excelled to some extent in her musical endeavors. She drew often; at ten, for example, she had drawn a good chalk likeness of her father.[10] She learned Italian, from Metastasio, on top of the necessary French and German, as well as Austrian history and French history, though from an Austrian perspective.[10] But while she flourished in her learning of Italian, her other languages proved to be a weak point. Conversations with her were stilted, and her ability to read and write German and French (the 'universal' language of Europe at this point in time) was undeniably poor.[15]

By many accounts, her childhood was somewhat complex. On the one hand, her parents had instituted several innovations in court life which made Austria one of the most progressive courts in Europe. While certain court functions remained formal by necessity, the Emperor and Empress nevertheless presided over many basic changes in court life. This included allowing relaxations in the type of people who could come to court (a change which allowed people of merit, as well as birth, to rise rapidly in the hierarchy of imperial favor at court),[citation needed] relatively lax dress etiquette, and the abolition of certain antiquated court rituals, including one in which dozens of courtiers could be present in the Empress' bedchamber while she gave birth. The Empress disliked the ritual, and would eject courtiers from her rooms when she went into labor.[16]

While she had an idyllic "private" life, her initial role in the political arena – and in her mother's main aim of alliance through marriage – was relatively small. Because there were so many other children who could be married off, Maria Antonia was sometimes neglected by her mother. As a result, she later described her relationship with her mother as one of awe-inspired fear.[17] She also developed a mistrust of intelligent older women as a result of her mother's close relationship with the Archduchess Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen, Marie Antoinette's older sister.[18]

Marriage to Louis: 1770–1793

The events leading to her eventual betrothal to the Dauphin of France began in 1765, when her father, Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, died of a stroke in August, leaving Maria Theresa to co-rule with her elder son and heir, the Emperor Joseph II.[19] By that time, marriage arrangements for several of Maria Antonia's sisters had begun: the Archduchess Maria Josepha was betrothed to King Ferdinand of Naples, and one of the remaining eligible archduchesses was tentatively set to marry Don Ferdinand of Parma. The purpose of these marriages was to cement the various complex alliances that Maria Theresa had entered into in the 1750s due to the Seven Years' War, which included Parma, Naples, Russia, and more importantly Austria's traditional enemy, France.[20] Without the Seven Years' War to "unite" the two countries briefly, the marriage of Maria Antonia and the Dauphin Louis-Auguste might not have occurred.

In 1767, a smallpox outbreak hit the family. Maria Antonia was one of the few who were immune to the disease because she already had had it at a young age. Her sister, Maria Josepha, came down with it after visiting the improperly sealed tomb of her sister-in-law (of the same name), and died quickly afterwards. This was not, however, due to her visit to the tomb; she must have been infected sometime before visiting the tomb, because the rash appeared only two days after her visit. Her mother, Maria Theresa, caught it and, though she survived, she suffered from the effects of the disease for the rest of her life. Her sister, Maria Elisabeth, caught it but survived. Her brother, Charles Joseph, and sister Maria Johanna, had already died of smallpox in 1761 and 1762 respectively.

This ultimately left 12-year-old Maria Antonia as the only potential bride left in the family for the 14-year-old Louis Auguste, who was also her second cousin once removed, through Leopold I. During the marriage negotiations, they lamented the crookedness of her teeth. Straightaway, a French doctor was called to perform some painful oral surgeries.[14] Performed without anesthesia and requiring three long months to take, at last Marie Antoinette's smile, "very beautiful and straight", satisfied France.[14] After painstaking work between the governments of France and Austria, the dowry was set at 200,000 crowns; as was the custom, portraits and rings were exchanged.[21] Finally, Antonia was married by proxy on 19 April in the Church of the Augustine Friars, Vienna; her brother Ferdinand stood in as the bridegroom. She was also officially restyled as Marie Antoinette, Dauphine of France.[22] Through her father, Marie Antoinette became the second (after Margaret of Valois, the renowned Queen Margot) French queen ever to descend from Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Marie Antoinette was officially handed over to her French relations on 7 May 1770, on an island on the Rhine River near Kehl. Chief among them were the comte de Noailles and his wife, the comtesse de Noailles, who had been appointed the Dauphine's Mistress of the Household by Louis XV.[23] She met the King, the Dauphin Louis-Auguste, and the royal aunts (Louis XV's daughters, known as Mesdames), one week later. Before reaching Versailles, she also met her future brothers-in-law, Louis Stanislas Xavier, comte de Provence; and Charles Philippe, comte d'Artois, who came to play important roles during and after her life.[24] Later, she met the rest of the family, including her husband's youngest sister, Madame Élisabeth, who at the end of Marie Antoinette's life would become her closest and most loyal friend.

The ceremonial wedding of the Dauphin and Dauphine took place on 16 May 1770, in the Palace of Versailles, after which was the ritual bedding.[25] It was assumed by custom that consummation of the marriage would take place on the wedding night. However, this did not occur, and the lack of consummation plagued the reputation of both Louis-Auguste and Marie Antoinette for seven years to come.[26]

The initial reaction to the marriage between Marie Antoinette and Louis-Auguste was decidedly mixed. On the one hand, the Dauphine herself was popular among the people. Her first official appearance in Paris on 8 June 1773 at the Tuileries was considered by many royal watchers a resounding success, with a reported 50,000 people crying out to see her. People were easily charmed by her personality and beauty. She had fair skin, straw-blond hair, and deep blue eyes.

Marie Antoinette, at the age of thirteen; this miniature portrait was sent to the dauphin, so he could see his bride before he met her, by Joseph Ducreux (1769).

Marie Antoinette, at the age of thirteen; this miniature portrait was sent to the dauphin, so he could see his bride before he met her, by Joseph Ducreux (1769).

However, at Court the match was not so popular among the elder members of court due to the long-standing tensions between Austria and France, which had only recently been mollified. Many courtiers had actively promoted a marriage between the dauphin and various Saxon princesses instead. Behind her back, Mesdames called Marie Antoinette "l'Autrichienne", the "Austrian woman." (Later, on the eve of the Revolution, and as Marie Antoinette's unpopularity grew, l'Autrichienne was easily transformed into l'Autruchienne, a pun making use of the words autruche "ostrich" and chienne "bitch".)[27] Others accused her of trying to sway the king to Austria's thrall, destroying long-standing traditions (such as appointing people to posts due to friendship and not to peerage), and of laughing at the influence of older women at the royal court.[28] Many other courtiers, such as the comtesse du Barry, had tenuous relationships with the Dauphine.

Her relationship with the comtesse du Barry was one which was important to rectify, at least on the surface, because Madame du Barry was the mistress of Louis XV, and thus had considerable political influence over the king. In fact, she had been instrumental ousting from power the duc de Choiseul, who had helped orchestrate the Franco-Austrian alliance as well as Marie Antoinette's own marriage. Louis XV's daughters, Mesdames, hated Mme du Barry due to her unsavory relationship with their father. With manipulative coaching, the aunts encouraged the Dauphine to refuse to acknowledge the favourite, which was considered by some to be a political blunder. After months of continued pressure from her mother and the Austrian minister, the comte de Mercy-Argenteau, Marie Antoinette grudgingly agreed to speak to Mme du Barry on New Year's Day 1772. Although the limit of their conversation was Marie Antoinette's banal comment to the royal mistress that, "there are a lot of people at Versailles today", Mme du Barry was satisfied and the crisis, for the most part, dissipated. There was, however, a further level of animosity from the view of the Mesdames raised by this situation – they felt somewhat 'betrayed' in their stance against du Barry.[29] Later, Marie Antoinette became more polite to the comtesse, pleasing Louis XV, but also particularly her mother.[30]

From the beginning, the Dauphine had to contend with constant letters from her mother, who wrote to her daughter regularly and who received secret reports from Mercy d'Argenteau on her daughter's behaviour. Marie Antoinette would write home in the early days saying that she missed her dear home. Though the letters were touching, in later years Marie Antoinette said she feared her mother more than she loved her.[31] Her mother constantly criticized her for her inability to "inspire passion" in her husband, who rarely slept with her and had no interest in doing so, being more interested in his hobbies such as lock-making and hunting. The Empress went so far as saying directly to Marie Antoinette that she was no longer pretty, and had lost all her grace.

Portrait of Marie Antoinette in hunting attire (a favorite of her mother), by Joseph Krantzinger (1771), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Portrait of Marie Antoinette in hunting attire (a favorite of her mother), by Joseph Krantzinger (1771), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

To make up for the lack of affection from her husband and the endless criticism of her mother, Marie Antoinette began to spend more on gambling and clothing, with cards and horse-betting, as well as trips to the city and new clothing, shoes, pomade and rouge.[32] She was expected by tradition to spend money on her attire, so as to outshine other women at Court, being the leading example of fashion in Versailles (the previous queen, Maria Leszczyńska, had died in 1768, two years prior to Marie Antoinette's arrival).

Marie Antoinette also began to form deep friendships with various ladies in her retinue. Most noted were the sensitive and "pure" widow, the princesse de Lamballe, whom she appointed as Superintendent of her Household, and the fun-loving, down-to-earth Yolande de Polastron, duchesse de Polignac, who eventually formed the cornerstone of the Queen's inner circle of friends (Société Particulière de la Reine).[33] The duchesse de Polignac later became the Governess of the royal children (Gouvernante des Enfants de France), and was a friend of both Marie Antoinette and Louis. The closeness of the Dauphine's friendship with these ladies, influenced by various popular publications which promoted such friendships, later caused accusations of lesbianism to be lodged against these women.[34] Others taken into her confidence at this time included her husband's brother, the comte d'Artois; their youngest sister, Madame Élisabeth; her sister-in-law, the comtesse de Provence; and Christoph Willibald Gluck, her former music teacher, whom she took under her patronage upon his arrival in France.[35]

On 27 April 1774, a week after the première of Gluck's opera, Iphigénie en Aulide, which had secured the Dauphine's position as a patron of the arts, Louis XV fell ill with smallpox. On 4 May, the dying king was pressured to send the comtesse du Barry away from Versailles; on 10 May, at 3 pm, he died at the age of 64.[36] Louis-Auguste was crowned King Louis XVI of France on 11 June 1775 at the cathedral of Rheims. Marie Antoinette was not crowned alongside him, merely accompanying him during the coronation ceremony.[37]

Reign: 1774–1792

1774–1778: Early years

From the outset, despite how she was portrayed in contemporary libelles, the new queen had very little political influence with her husband. Louis, who had been influenced as a child by anti-Austrian sentiments in the court, blocked many of her candidates, including Choiseul,[38] from taking important positions, aided and abetted by his two most important ministers, Chief Minister Maurepas and Foreign Minister Vergennes. All three were anti-Austrian, and were wary of the potential repercussions of allowing the queen – and, through her, the Austrian empire – to have any say in French policy.[39]

Archduke Maximilian Francis of Austria visited Marie Antoinette and her husband on 7 February 1775 at the Château de la Muette.

Archduke Maximilian Francis of Austria visited Marie Antoinette and her husband on 7 February 1775 at the Château de la Muette.

Marie Antoinette's situation became more precarious when, on 6 August 1775, her sister-in-law, the comtesse d'Artois, gave birth to a son, the duc d'Angoulême (who later became the presumptive heir to the French throne when his father, the comte d'Artois, became King Charles X of France in 1824). This resulted in release of a plethora of graphic satirical pamphlets, which mainly centered on the king's impotence and the queen's searching for sexual relief elsewhere, with men and women alike. Among her rumored lovers were her close friend, the princesse de Lamballe, and her handsome brother-in-law, the comte d'Artois, with whom the queen had a good rapport.[40]

This caused the queen to plunge further into the costly diversions of buying her dresses from Rose Bertin and gambling, simply to enjoy herself. On one famed occasion, she played for three days straight with players from Paris, straight up until her 21st birthday. She also began to attract various male admirers whom she accepted into her inner circles, including the baron de Besenval, the duc de Coigny, and Count Valentin Esterházy.[41]

She was given free rein to renovate the Petit Trianon, a small château on the grounds of Versailles, which was given to her as a gift by Louis XVI on 15 August 1774; she concentrated mainly on horticulture, redesigning in the English mode the garden, which in the previous reign had been an arboretum of introduced species. Although the Petit Trianon had been built for Louis XV's mistress, Madame de Pompadour, it became associated with Marie Antoinette's perceived extravagance. Rumors circulated that she plastered the walls with gold and diamonds.[42]

"...the innovativeness of Marie Antoinette's country retreat would attract her subjects’ fierce disapproval, even as it aimed to bolster her autonomy and enhance her prestige," (Weber 132).

An even bigger problem, however, was the debt incurred by France during the Seven Years' War, still unpaid. It was further exacerbated by Vergennes' prodding Louis XVI to get involved in Great Britain's war with its North American colonies, due to France's traditional rivalry with Great Britain.[43]

In the midst of preparations for sending help to France, and in the atmosphere of the first wave of libelles, Holy Roman Emperor Joseph came to call on his sister and brother-in-law on 18 April 1777, the subsequent six-week visit in Versailles a part of the attempt to figure out why their marriage had not been consummated.

It was due to Joseph's intervention that, on 30 August 1777, the marriage was officially consummated. Eight months later, in April, it was suspected that the queen was finally pregnant with her first child. This was confirmed on 16 May 1778.[44]

1778–1781: Motherhood

Marie Antoinette in a court dress worn over extremely wide panniers, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1778).

Marie Antoinette in a court dress worn over extremely wide panniers, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1778).

In the middle of her pregnancy, two events occurred which had a profound impact on the queen's later life. First, there was the return of the handsome Swede, Count Axel von Fersen – whom she had met previously on New Year's Day, 1774, while she was still Dauphine – to Versailles for two years. Secondly, the king's wealthy but spiteful cousin, the duc de Chartres, was disgraced due to his questionable conduct during the Battle of Ouessant against the British. In addition, Marie Antoinette's brother, the Emperor Joseph, began making claims on the throne of Bavaria based upon his second marriage to the princess Maria Josepha of Bavaria. Marie Antoinette pleaded with her husband for the French to help intercede on behalf of Austria but was rebuffed by the king and his ministers. The Peace of Teschen, signed on 13 May 1779, ended the brief conflict, but the incident once more showed the limited influence that the queen had in politics.[45]

Marie Antoinette's daughter, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, given the honorific title at birth of Madame Royale, was finally born at Versailles, after a particularly difficult labour, on 19 December 1778, following an ordeal where the queen literally collapsed from suffocation and hemorrhaging. The queen's bedroom was packed with courtiers watching the birth, and the doctor aiding her supposedly caused the excessive bleeding by accident. The windows had to be torn out to revive her. This incident has a variant: some sources purport that it was the Princesse de Lamballe who lost consciousness, and to prevent the queen from doing the same, the king himself – rather unusually – let in some air by tearing off the tapes that sealed the windows.[46] In any case, as a result of this harrowing experience, the queen and the king banned most courtiers from entering her bedchamber for subsequent labours.[47]

The baby's paternity was contested in the libelles but not by the king himself, who was close to his daughter.[48]

The birth of a daughter meant that pressure to have a male heir continued, and Marie Antoinette wrote about her worrisome health, which might have contributed to a miscarriage in July 1779. Antonia Fraser expresses doubts as to whether there was a pregnancy in 1779, ascribing the queen's belief that she had a miscarriage to Antoinette's irregular menstrual cycle. The memoirs of the queen's lady-in-waiting, Madame Campan, state explicitly that the miscarriage came about after the queen exerted herself too strenuously in closing a window in her carriage, felt that she had hurt herself, and lost the child eight days later. Campan adds that the king spent a morning consoling the queen at her bedside, and swore to secrecy all those who were aware of the accident.[49]

Meanwhile, the queen began to institute changes in the customs practised at court, with the approval of the king. Some changes, such as the abolition of segregated dining spaces, had already been instituted for some time and had been met with disapproval from the older generation. More importantly was the abandonment of heavy make-up and the popular wide-hooped panniers for a more simple feminine look, typified first by the rustic robe à la polonaise and later by the 'gaulle,' a simple muslin dress that she wore in a 1783 Vigée-Le Brun portrait. She also began to participate in amateur plays and musicals, starting in 1780, in a theatre built for her and other courtiers who wished to indulge in the delights of acting and singing.[50]

In 1780, two candidates who had been supported by Marie Antoinette for positions, the marquis de Castries, and the comte de Ségur, were appointed Minister of the Navy and Minister of War, respectively. Though many believed it was entirely the support of the queen that enabled them to secure their positions, in truth it was mostly that of Finance Minister Jacques Necker.[51]

Marie Antoinette en chemise, portrait of the queen in a "muslin" dress, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1783). This controversial portrait was viewed by her critics to be improper for a queen.

Marie Antoinette en chemise, portrait of the queen in a "muslin" dress, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1783). This controversial portrait was viewed by her critics to be improper for a queen.

Later that year, Empress Maria Theresa began to fall ill with dropsy and an unnamed respiratory problem. She died on 29 November 1780, in Vienna, at the age of 63, and was mourned throughout Europe. Marie Antoinette was worried that the death of her mother would jeopardise the Franco-Austrian alliance (as well as, ultimately, herself), but Emperor Joseph reassured her through his own letters (as the empress had not stopped writing to Marie Antoinette until shortly before her death) that he had no intention of breaking the alliance.

Three months after the empress' death, it was rumoured that Marie Antoinette was pregnant again, which was confirmed in March 1781. Another royal visit from Joseph II in July, partially to reaffirm the Franco-Austrian alliance and also a means of seeing his sister again, was tainted with false rumours that Marie Antoinette was siphoning treasury money to him.[52]

On 22 October 1781, the queen gave birth to Louis Joseph Xavier François, who bore the title Dauphin of France, as was customary for the eldest son of the King of France. The reaction to the birth of an heir was best summed up by the words of Louis XVI himself, as he wrote them down in his hunting journal: "Madame, you have fulfilled our wishes and those of France, you are the mother of Dauphin".[53] He would, according to courtiers, try to frame sentences to put in the phrase "my son the Dauphin" in the weeks to come.[54] It also helped that, three days before the birth, the majority of the fighting in the conflict in America had been concluded with the surrender of General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.[55]

1782–1785: Declining popularity

Despite the general celebration over the birth of the Dauphin, Marie Antoinette's political influence, such as it was, did not benefit Austria.[citation needed] Instead, after the death of the comte de Maurepas, the influence of Vergennes was strengthened, and she was again left out of political affairs. The same happened during the so-called Kettle War, in which her brother Joseph attempted to open up the Scheldt River for naval passage. Later, another attempt by him to claim Bavaria was rebuffed as being against French interests.[56]

When accused of being a "dupe" by her brother for her political inaction, Marie Antoinette responded that she had little power.[citation needed] The king rarely talked to her about policy, and his anti-Austrian education as a child fortified his refusals in allowing his wife any participation in his decisions. As a result, she had to pretend to his ministers that she was in his full confidence in order to get the information she wanted.[citation needed] This led the court to believe she had more power than she did. As she wrote, "Would it be wise of me to have scenes with his (Louis XVI's) ministers over matters on which it is practically certain the King would not support me?"[57]

Her temperament was more suited to personally directing the education of her children. This was against the traditions of Versailles, where the queen usually had little say over the Enfants de France, as the royal children were called, and they were instead handed over to various courtiers who fought over the privilege. In particular, after the royal governess at the time of the Dauphin's birth, the princesse de Guéméné, went bankrupt and was forced to resign, there was a controversy over who should replace her. Marie Antoinette appointed her favourite, the duchesse de Polignac, to the position. This met with disapproval from the court, as the duchess was considered to be of too "immodest" a birth to occupy such an exalted position.[citation needed] On the other hand, both the king and queen trusted Mme de Polignac completely, and the duchess had children of her own to whom the queen had become attached.[58]

In June 1783, Marie Antoinette was pregnant again. That same month, Count Axel von Fersen returned from America, in order to secure a military appointment, and he was accepted into her private society. He left in September to become a captain of the bodyguard for his sovereign, Gustavus III, the king of Sweden, who was conducting a tour of Europe.[citation needed] Marie Antoinette suffered a miscarriage on the night of 1–2 November 1783, prompting more fears for her health.[59]

Marie Antoinette with her two eldest children, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte and the Dauphin Louis Joseph, in the Petit Trianon's gardens, by Adolf Ulrich Wertmüller (1785).

Marie Antoinette with her two eldest children, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte and the Dauphin Louis Joseph, in the Petit Trianon's gardens, by Adolf Ulrich Wertmüller (1785).

Trying to calm her mind, during Fersen's first visit, and later after his return on 7 June 1784, the queen occupied herself with the creation of the Hameau de la reine, a model hamlet in the garden of the Petit Trianon with a mill and 12 cottages, 9 of which are still standing. The Hameau was one of Marie Antoinette's contributions to augmenting the chateau at Versailles and it can to this day be viewed by the public. Its creation, however, unexpectedly caused another uproar when the actual price of the Hameau was inflated by her critics.[citation needed] In truth, it was copied from another, far grander "model village" built in 1774 for the prince de Condé on his estate at Chantilly. The comtesse de Provence's version included windmills and a marble dairyhouse.[60] Started in 1783 and finished in 1787, to designs of the Queen's favoured architect, Richard Mique, the hamlet was complete with farmhouse, dairy, and mill.[61] Public records indicate that in 1781 the Comtesse de Provence's bought land for her Hameau which was completed in 1783, just before work started on the Queen's Hameau.[62] Also, the "Temple of Love" (a physical structure built as a part of the Queen's Hameau) bears a marked and striking resemblance to the rotunda of the Pavillon de Musique, which was the folie built by the Comtesse de Provence situated in her Hameau.[63]

In addition to the creation of the Hameau, Marie Antoinette had other notable interests and activities. She became an avid reader of historical novels, and her scientific interest was piqued enough to become a witness to the launching of hot air balloons.[citation needed] She was fascinated by Rousseau's "back to nature" philosophy, as well as the culture of the Incas of Peru and their worship of the sun, about which she had books in her library. Briefly, she even sought out important British personages such as the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, and the British ambassador to France, the Duke of Dorset.[64] She also developed an interest in learning English, and while she never became fluent, she was able to write in broken English to her friend, the Duchess of Devonshire, whose life was very similar to her own.[citation needed]

Despite the many things which she did in her spare time, her primary concern became the health of the Dauphin, which was beginning to fail. By the time Fersen returned to Versailles in 1784, it was widely thought that the sickly Dauphin would not live to be an adult. As a consequence, it was rumored that the king and queen were attempting to have another child.[59] During this time, Beaumarchais' play The Marriage of Figaro premiered in Paris. After initially having been banned by the king due to its negative portrayal of the nobility, the play was ironically finally allowed to be publicly performed because of its overwhelming popularity at court, where secret readings of it had been given.[65]

In August 1784, the queen reported that she was pregnant again. With the future enlargement of her family in mind, she bought the Château de Saint-Cloud, a place she had always loved, from the duc d'Orléans, the father of the previously disgraced duc de Chartres. She intended to leave it as an inheritance to her younger children without stipulation, but later realized that her children would not appreciate it. This was a hugely unpopular acquisition, particularly with some factions of the nobility who already disliked her, but also with a growing percentage of the population who felt shocked that a French queen might own her own residence, independent of the king. Despite having the baron de Breteuil working on her behalf, the purchase did not help improve the public's frivolous image of the queen. The château's expensive price, almost 6 million livres, plus the substantial extra cost of redecorating it, ensured that there was less money going towards repaying France's substantial debt.[66]

On 27 March 1785, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a second son, Louis Charles, who was created the duc de Normandie. Louis Charles was visibly stronger than the sickly Dauphin, and the new baby was affectionately nicknamed by the queen, chou d'amour.[67] The fact that this delivery occurred exactly nine months following Fersen's visit did not escape the attention of many, and though there is much doubt and historical speculation about the parentage of this child, public opinion towards her decreased noticeably.[68] These suspicions of illegitimacy, along with the continued publication of the libelles, a never-ending cavalcade of court intrigues, the actions of Joseph II in the Kettle War, and her purchase of Saint-Cloud combined to sharply turn popular opinion against the queen, and the image of a licentious, spendthrift, empty-headed foreign queen was quickly taking root in the French psyche.[69]

1786-1789: Prelude to revolution

A second daughter, Sophie Hélène Béatrice de France, was born on 9 July 1786, but died on 19 June 1787.

The continuing deterioration of the financial situation in France – despite the fact that cutbacks in the royal retinue had been made – ultimately forced the king, in collaboration with his current Minister of Finance, Calonne, to call the Assembly of Notables, after a hiatus of 160 years. The assembly was held to try to pass some of the reforms needed to alleviate the financial situation when the Parlements refused to cooperate. The first meeting of the assembly took place on 22 February 1787, at which Marie Antoinette was not present. Later, her absence resulted in her being accused of trying to undermine the purpose of the assembly .[70]

However, the Assembly was a failure with or without the queen, as it did not pass any reforms and instead fell into a pattern of defying the king, demanding other reforms and for the acquiescence of the Parlements. As a result, the king dismissed Calonne on 8 April 1787; Vergennes died on 13 February. The king, once more ignoring the queen's pro-Austrian candidate, appointed a childhood friend, the comte de Montmorin, to replace Vergennes as Foreign Minister.[71]

During this time, even as her candidate was rejected, the queen began to abandon her more carefree activities to become more involved in politics than ever before, and mostly against the interests of Austria.[citation needed] This was for a variety of reasons. First, her children were Enfants de France, and thus their future as leaders of France needed to be assured. Second, by concentrating on her children, the queen sought to improve the dissolute image she had acquired from the "Diamond Necklace Affair", in which she had been accused of participating in a crime to defraud the crown jewelers of the cost of a very expensive diamond necklace. Third, the king had begun to withdraw from a decision-making role in government due to the onset of an acute case of depression from all the pressures he was under. The symptoms of this depression were passed off as drunkenness by the libelles. As a result, Marie Antoinette finally emerged as a politically viable entity, although that was never her actual intention. In her new capacity as a politician with a degree of power, the queen tried her best to help the situation brewing between the assembly and the king.[71]

This change in her political role signalled the beginning of the end of the influence of the duchesse de Polignac, as Marie Antoinette began to dislike the duchesse's huge expenditures and their impact on the finances of the Crown. The duchesse left for England in May, leaving her children behind in Versailles. Also in May, Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne, the archbishop of Toulouse and one of the queen's political allies, was appointed by the king to replace Calonne as the Finance Minister. He began instituting more cutbacks at court.[72]

Brienne, though, was not able to improve the financial situation. Since he was her ally, this failure adversely affected the queen's political position. The continued poor financial climate of the country resulted in the 25 May dissolution of the Assembly of Notables because of its inability to get things done. This lack of solutions was unfairly blamed on the queen.[citation needed] In reality, the blame should have been placed on a combination of several other factors. There had been too many expensive wars, a too-large royal family whose large frivolous expenditures far exceeded those of the queen, and an unwillingness on the part of many of the aristocrats in charge to help defray the costs of the government out of their own pockets with higher taxes.[citation needed] Marie Antoinette earned the nickname of "Madame Déficit" in the summer of 1787 as a result of the public perception that she had singlehandedly ruined the finances of the nation.[73]

The queen attempted to fight back with her own propaganda that portrayed her as a caring mother, most notably with the portrait of her and her children done by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, which premiered at the Royal Académie Salon de Paris in August 1787.[74][75] This attack strategy was eventually dropped, however, because of the death of the queen's youngest child, Sophie. Around the same time, Jeanne de Lamotte-Valois escaped from prison in France and fled to London, where she published more damaging lies concerning her supposed "affair" with the queen.[76]

The political situation in 1787 began to worsen when the Parlement was exiled, and culminated on 11 November, when the king tried to use a lit de justice to force through legislation. He was unexpectedly challenged by his formerly disgraced cousin, the duc de Chartres, who had inherited the title of duc d'Orléans at the death of his father in 1785. The new duc d'Orléans publicly protested the king's actions, and was subsequently exiled. The May Edicts issued on 8 May 1788 were also opposed by the public. Finally, on 8 July and 8 August, the king announced his intention to bring back the Estates General, the traditional elected legislature of the country which had not been convened since 1614.[77]

Marie Antoinette was not directly involved with the exile of the Parlement, the May Edicts or with the announcement regarding the Estates General. Her primary concern in late 1787 and 1788 was instead the improved health of the Dauphin. He was suffering from tuberculosis, which in his case had twisted and curved his spinal column severely. He was brought to the château at Meudon in the hope that its country air would help the young boy recover. Unfortunately, the move did little to alleviate the Dauphin's condition, which gradually continued to deteriorate.[78]

The queen, however, was present with her daughter, Marie-Therese, when Tippu Sahib of Mysore visited Versailles seeking help against the British. More importantly she was instrumental in the recall of Jacques Necker as Finance Minister on 26 August, a popular move, even though she herself was worried that the recall would again go against her if Necker was unsuccessful in reforming the country's finances.[79]

Her prediction began to come true when bread prices started to rise due to the severe 1788–1789 winter.[citation needed] The Dauphin's condition worsened even more, riots broke out in Paris in April, and on 26 March, Louis XVI himself almost died from a fall off the roof.[citation needed]

"Come, Léonard, dress my hair, I must go like an actress, exhibit myself to a public that may hiss me",[14] the queen quipped to her hairdresser, who was one of her "ministers of fashion", as she prepared for the Mass celebrating the return of the Estates General on 4 May 1789. She knew that her rival, the duc d'Orléans, who had given money and bread to the people during the winter, would be popularly acclaimed by the crowd much to her detriment.[citation needed] The Estates General convened the next day.[80] During the month of May, the Estates General began to fracture between the democratic Third Estate (consisting of the bourgeoisie and radical nobility), and the royalist nobility of the Second Estate, while the king's brothers began to become more hardline.

Despite these developments, the queen was strongly focused on thoughts for her son, the dying Dauphin. With his mother at his side, the seven-year old boy passed away at Meudon on 4 June, succumbing to tuberculosis, and leaving the title of Dauphin to his younger brother, Louis Charles. His death, which would have normally been nationally mourned, was virtually ignored by the French people,[citation needed] who were instead preparing for the next meeting of the Estates General, and hoping for a resolution to the bread crisis. As the Third Estate declared itself a National Assembly and took the Tennis Court Oath, and as others listened to rumors that the queen wished to bathe in their blood, Marie Antoinette went into mourning for her eldest son.[81]

July 1789–1792: The French Revolution

The situation began to escalate violently in June as the National Assembly began to demand more rights, and Louis XVI began to push back with efforts to suppress the Third Estate. However, the king's ineffectiveness and the queen's unpopularity undermined the monarchy as an institution, and so these attempts failed. Then, on 11 July, Necker was dismissed. Paris was besieged by riots at the news, which culminated in the storming of the Bastille on 14 July.[82]

In the days and weeks that followed, many of the most conservative, reactionary royalists, including the comte d'Artois and the duchesse de Polignac, fled France for fear of assassination. Marie Antoinette, whose life was the most in danger, stayed behind in order to help the king promote stability, even as his power was gradually being taken away by the National Constituent Assembly, which was now ruling Paris and conscripting men to serve in the Garde Nationale.[83]

By the end of August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (La Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen) was adopted, which officially created the beginning of a constitutional monarchy in France.[84] Despite this, the king was still required to perform certain court ceremonies, even as the situation in Paris became worse due to a bread shortage in September. On 5 October, a mob from Paris descended upon Versailles and forced the royal family, along with the comte de Provence, his wife and Madame Elisabeth, to move to Paris under the watchful eye of the Garde Nationale. The king and queen were installed in the Tuileries Palace under surveillance.[85] During this limited house arrest, Marie Antoinette conveyed to her friends that she did not intend to involve herself any further in French politics, as everything, whether or not she was involved, would inevitably be attributed to her anyway and she feared the repercussions of further involvement.[86]

Despite the situation, Marie Antoinette was still required to perform charitable functions and to attend certain religious ceremonies, which she did. Most of her time, however, was dedicated to her children.[87]

Despite her attempts to remain out of the public eye, she was falsely accused in the libelles of having an affair with the commander of the Garde Nationale, the marquis de La Fayette. In reality, she loathed the marquis for his liberal tendencies and for being partially responsible for the royal family's forced departure from Versailles.[88] This was not the only accusation Marie Antoinette faced from such "libelles." In such pamphlets as "Le Godmiché Royal", (translated, "The Royal Dildo"), it was suggested that she routinely engaged in deviant sexual acts of various sorts, most famously with the English Baroness 'Lady Sophie Farrell' of Bournemouth, a renowned lesbian of the time.[89] From acting as a tribade, (in her case in the lesbian sense), to sleeping with her son, Marie Antoinette was constantly an object of rumor and false accusations of committing sexual acts with partners other than the king. Later, allegations of this sort (from incest to orgiastic excesses) were used to justify her execution. Ultimately, none of the charges of sexual depravity have any credible evidentiary support. Marie Antoinette was simply an easy target for rumor and criticism.

Constantly monitored by revolutionary spies within her own household, the queen played little or no part in the writing of the French Constitution of 1791, which greatly weakened the king's authority. She, nevertheless, hoped for a future where her son would still be able to rule, convinced that the violence would soon pass.[90]

During this time, there were many plots designed to help members of the royal family escape. The queen rejected several because she would not leave without the king. Other opportunities to rescue the family were ultimately frittered away by the indecisive king. Once the king finally did commit to a plan, his indecision played an important role in its poor execution and ultimate failure. In an elaborate attempt to escape from Paris to the royalist stronghold of Montmédy planned by Count Axel von Fersen and the baron de Breteuil, some members of the royal family were to pose as the servants of a wealthy Russian baroness. Initially, the queen rejected the plan because it required her to leave with only her son. She wished instead for the rest of the royal family to accompany her. The king wasted time deciding upon which members of the family should be included in the venture, what the departure date should be, and the exact path of the route to be used. After many delays, the escape ultimately occurred on 21 June 1791, and was a failure. The entire family was captured twenty-four hours later at Varennes and taken back to Paris within a week.[91]

The result of the fiasco was a further decline in the popularity of both the king and queen. The Jacobin Party successfully exploited the failed escape to advance its radical agenda. Its members called for the end to any type of monarchy in France.[92]

Though the new constitution was adopted on 3 September, Marie Antoinette hoped through the end of 1791 that the political drift she saw occurring toward representative democracy could be stopped and rolled back. She fervently hoped that the constitution would prove unworkable, and also that her brother, the new Holy Roman emperor, Leopold II, would find some way to defeat the revolutionaries. However, she was unaware that Leopold was more interested in taking advantage of France's state of chaos for the benefit of Austria than in helping his sister and her family, despite many demands from both citizens and even soldiers to have the Austrian Army invade France and rescue Marie.[93]

The result of Leopold's aggressive tendencies, and those of his son Francis II, who succeeded him in March, was that France declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792. This caused the queen to be viewed as an enemy, even though she was personally against Austrian claims on French lands. The situation became compounded in the summer when French armies were continually being defeated by the Austrians and the king vetoed several measures that would have restricted his power even further. During this time, due to his political activities, Louis received the nickname "Monsieur Veto" – and the name "Madame Veto" was likewise subsequently bequeathed on Marie Antoinette.[94] These names were then prominently featured in different contexts, including La Carmagnole.

Marie Antoinette with her children and Madame Élisabeth, when the mob broke into the Tuileries Palace on 20 June 1792.

Marie Antoinette with her children and Madame Élisabeth, when the mob broke into the Tuileries Palace on 20 June 1792.

On 20 June, "a mob of terrifying aspect" broke into the Tuileries and made the king wear the bonnet rouge (red Phrygian cap) to show his loyalty to France.[95]

The vulnerability of the king was exposed on 10 August when an armed mob, on the verge of forcing its way into the Tuileries Palace, forced the king and the royal family to seek refuge at the Legislative Assembly. An hour and a half later, the palace was invaded by the mob who massacred the Swiss Guards.[96] On 13 August, the royal family was imprisoned in the tower of the Temple in the Marais under conditions considerably harsher than their previous confinement in the Tuileries.[97]

A week later, many of the royal family's attendants, among them the princesse de Lamballe, were taken in for interrogation by the Paris Commune. Transferred to the La Force prison, she was one of the victims of the September Massacres, killed on 3 September. Her head was affixed on a pike and marched through the city. Although Marie Antoinette did not see the head of her friend as it was paraded outside her prison window, she fainted upon learning about the gruesome end that had befallen her faithful companion.[98]

On 21 September, the fall of the monarchy was officially declared, and the National Convention became the legal authority of France. The royal family was re-styled as the non-royal "Capets". Preparations for the trial of the king in a court of law began.[99]

Charged with undermining the First French Republic, Louis was separated from his family and tried in December. He was found guilty by the Convention, led by the Jacobins who rejected the idea of keeping him as a hostage. However, the sentence did not come until one month later, when he was condemned to execution by guillotine.[100]

1793: "Widow Capet" and death

Marie Antoinette on the way to the guillotine. (Pen and ink by Jacques-Louis David, 16 October 1793)

Marie Antoinette on the way to the guillotine. (Pen and ink by Jacques-Louis David, 16 October 1793)

Louis was executed on 21 January 1793, at the age of thirty-eight.[101] The result was that the "Widow Capet", as the former queen was called after the death of her husband, plunged into deep mourning; she refused to eat or do any exercise. There is no knowledge of her proclaiming her son as Louis XVII; however, the comte de Provence, in exile, recognised his nephew as the new king of France and took the title of Regent. Marie-Antoinette's health rapidly deteriorated in the following months. By this time she suffered from tuberculosis and possibly uterine cancer, which caused her to hemorrhage frequently.[102]

Despite her condition, the debate as to her fate was the central question of the National Convention after Louis's death. There were those who had been advocating her death for some time, while some had the idea of exchanging her for French prisoners of war or for a ransom from the Holy Roman Emperor. Thomas Paine advocated exile to America.[103] Starting in April, however, a Committee of Public Safety was formed, and men such as Jacques Hébert were beginning to call for Antoinette's trial; by the end of May, the Girondins had been chased out of power and arrested.[104] Other calls were made to "retrain" the Dauphin, to make him more pliant to revolutionary ideas. This was carried out when the eight year old boy Louis Charles was separated from Antoinette on 3 July, and given to the care of a cobbler.[105] On 1 August, she herself was taken out of the Tower and entered into the Conciergerie as Prisoner No. 280.[106] Despite various attempts to get her out, such as the Carnation Plot in September, Marie Antoinette refused when the plots for her escape were brought to her attention.[107] While in the Conciergerie, she was attended by her last servant, Rosalie Lamorlière.

She was finally tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal on 14 October. Unlike the king, who had been given time to prepare a defence, the queen's trial was far more of a sham, considering the time she was given (less than one day). Among the things she was accused of (most, if not all, of the accusations were untrue and probably lifted from rumours begun by libelles) were orchestrating orgies in Versailles, sending millions of livres of treasury money to Austria, plotting to kill the Duke of Orléans, incest with her son, declaring her son to be the new king of France and orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss Guards in 1792.

The most infamous charge was that she sexually abused her son. This was according to Louis Charles, who, through his coaching by Hébert and his guardian, accused his mother. After being reminded that she had not answered the charge of incest, Marie Antoinette protested emotionally to the accusation, and the women present in the courtroom – the market women who had stormed the palace for her entrails in 1789 – ironically began to support her.[108] She had been composed throughout the trial until this accusation was made, to which she finally answered, "If I have not replied it is because Nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother."

However, in reality the outcome of the trial had already been decided by the Committee of Public Safety around the time the Carnation Plot was uncovered, and she was declared guilty of treason in the early morning of 16 October, after two days of proceedings.[109] Back in her cell, she composed a moving letter to her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth, affirming her clear conscience, her Catholic faith and her feelings for her children. The letter did not reach Élisabeth.[110]

Funerary monument to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, sculptures by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot in the Basilica of St Denis

Funerary monument to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, sculptures by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot in the Basilica of St Denis

On the same day, her hair was cut off and she was driven through Paris in an open cart, wearing a simple white dress. At 12:15 pm, two and a half weeks before her thirty-eighth birthday, she was executed at the Place de la Révolution (present-day Place de la Concorde).[111][112] Her last words were "Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it", to Henri Sanson the executioner, whose foot she had accidentally stepped on after climbing the scaffold. Her body was thrown into an unmarked grave in the Madeleine cemetery, rue d'Anjou, (which was closed the following year).

Her sister-in-law Élisabeth was executed in 1794 and her son died in prison in 1795. Her daughter returned to Austria in a prisoner exchange, married and died childless in 1851.[113]

Both her body and that of Louis XVI were exhumed on 18 January 1815, during the Bourbon Restoration, when the comte de Provence had become King Louis XVIII. Christian burial of the royal remains took place three days later, on 21 January, in the necropolis of French Kings at the Basilica of St Denis.[114]

Historical legacy and popular culture

The phrase "Let them eat cake" is often attributed to Marie Antoinette. However, there is no evidence to support that she ever uttered this phrase, and it is now generally regarded as a "journalistic cliché".[115] It originally appeared in Book VI of the first part (finished in 1767, published in 1782) of Rousseau's putative autobiographical work, Les Confessions.

Enfin je me rappelai le pis-aller d’une grande princesse à qui l’on disait que les paysans n’avaient pas de pain, et qui répondit : Qu’ils mangent de la brioche.

Finally I recalled the stopgap solution of a great princess who was told that the peasants had no bread, and who responded: "Let them eat brioche."Apart from the fact that Rousseau ascribes these words to an unknown princess – vaguely referred to as a 'great princess', there is some level of thought that he invented it altogether, seeing as Confessions was, on the whole, a rather inaccurate autobiography.[116]

In America, expressions of gratitude to France for its help in the American Revolution included the naming of the city of Marietta, Ohio, founded in 1788. The Ohio Company of Associates chose the name Marietta after an affectionate nickname for Marie Antoinette.[117]

Titles from birth to death

- 2 November 1755 – 19 April 1770: Her Royal Highness Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria

- 19 April 1770 – 10 May 1774: Her Royal Highness The Dauphine of France

- 10 May 1774 – 1 October 1791: Her Majesty The Queen of France and Navarre

- 1 October 1791 – 21 September 1792: Her Majesty The Queen of the French

- 21 September 1792 - 21 January 1793: Madame Capet

- 21 January 1793 – 16 October 1793: La Veuve ("the widow") Capet

Ancestry

Notes

- ^ a b Lever 2006, p. 1

- ^ C. f. "it is both impolitic and immoral for palaces to belong to a Queen of France" (part of a speech by a councilor in the Parlement de Paris, early 1785, after Louis XVI bought St Cloud chateau for the personal use of Marie Antoinette), quoted in Castelot 1957, p. 233

- ^ C.f. the following quote: "she (Marie Antoinette) thus obtained promises from Louis XVI which were in contradiction with the Council's (of Louis XVI's ministers) decisions", quoted in Castelot 1957, p. 186

- ^ "Marie Antoinette Biography". Chevroncars.com. http://www.chevroncars.com/learn/famous-people/marie-antoinette. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ^ "A Reputation in Shreds - Marie Antoinette Online". Marie-antoinette.org. http://www.marie-antoinette.org/category/reputation/. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ^ "Marie Antoinette". Antonia Fraser. http://www.antoniafraser.com/antoinette.aspx. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ^ Konigsberg, Eric (2006-10-22). "Marie Antoinette, Citoyenne". NYTimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/22/weekinreview/22marie.html. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ^ Fraser 2002, p. 5

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g Cronin 1989, p. 45

- ^ Lever 2006, p. 7

- ^ Lever 2006, p. 10

- ^ Cronin 1989, p. 46

- ^ a b c d e f g Weber 2007[page needed]

- ^ Fraser 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ After the problems encountered at the birth of Marie Antoinette's first child, Marie Therese in 1778, her husband, King Louis XVI, did not allow the public in his wife's bedroom at the birth their other children, and let only a handful of trusted courtiers witness the birth of the dauphin Louis Joseph on 22 October 1781. Fraser 2001, pp. 166–170

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 22

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 23

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 42–50.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 58–62.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 64–69.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 157.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 94, 130–31.

- ^ Lever 2006.[page needed]

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 87–90, 97–99.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 141.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 131–132; Bonnet 1981

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 113–116.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 132–137.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 124–127.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 140–145.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 152.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Hibbert 2002, p. 23

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 172.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 174–179.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 184–187.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 191.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 194.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 198–201.

- ^ a b Fraser 2001, p. 202.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Lever 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Dams & Zega 1995, pp. 130–131

- ^ Seulliet 2008, p. 116

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 208.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 216–220.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Lever 2006, p. 189

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 226.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 246–248.

- ^ a b Fraser 2001, pp. 248–250.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 250–255.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Facos, p. 12.

- ^ Schama, p. 221.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 255–258.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 270–273.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 274–278.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 282–284.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 284–289.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 289.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 298–304.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 304.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 304–308.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 319.

- ^ "Project MUSE — Early American Literature — Charles Brockden Brown's Ormond and Lesbian Possibility in the Early Republic". Muse.jhu.edu. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/early_american_literature/v040/40.1comment.pdf. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 333–348.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 350–352.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 354–359.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 365–368.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 368.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 373–379.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 382–386.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 389.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 392.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 395–398.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 399.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 404–405, 408.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 398, 408.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 411–412.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 412–414.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 414–415.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 418.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 429–435.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 424–425, 436.

- ^ "Last Letter of Marie-Antoinette", Tea at Trianon, 26 May 2007, http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2007/05/last-letter-of-marie-antoinette.html

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 440.

- ^ The Times 23 October 1793, The Times.

- ^ Richard Covington (November 2006), "Marie Antoinette", Smithsonian magazine, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/biography/marieantoinette.html

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 411, 447.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. xviii, 160; Lever 2006, pp. 63–5; Lanser 2003, pp. 273–290

- ^ Johnson 1990, p. 17

- ^ Sturtevant, pp. 14, 72.

References

- Bonnet, Marie-Jo (1981) (in French). Un choix sans équivoque: recherches historiques sur les relations amoureuses entre les femmes, XVIe-XXe siècle. Paris: Denoël. OCLC 163483785.

- Castelot, André (1957). Queen of France: a biography of Marie Antoinette. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 301479745.

- Cronin, Vincent (1989). Louis and Antoinette. London: The Harvill Press. ISBN 9780002720212.

- Dams, Bernd H.; Zega, Andrew (1995). La folie de bâtir: pavillons d'agrément et folies sous l'Ancien Régime. trans. Alexia Walker. Flammarion. ISBN 9782082018586.

- Facos, Michelle (2011). An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-84071-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=Vk4WgsO2OZsC&pg=PA12. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette (1st ed.). New York: N.A. Talese/Doubleday. ISBN 9780385489485.

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey (2nd ed.). Garden City: Anchor Books. ISBN 9780385489492.

- Hermann, Eleanor (2006). Sex With The Queen. Harper/Morrow. ISBN 0-0608-4673-9.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2002). The Days of the French Revolution. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0688169783.

- Johnson, Paul (1990). Intellectuals. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060916572.

- Lanser, Susan S. (2003). "Eating Cake: The (Ab)uses of Marie-Antoinette". In Goodman, Dena. Marie-Antoinette: Writings on the Body of a Queen. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415933957.

- Lever, Évelyne (2006). Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. London: Portrait. ISBN 9780749950842.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0679726101.

- Seulliet, Philippe (July 2008). "Swan Song: Music Pavillion of the Last Queen of France". World Of Interiors.

- Sturtevant, Lynne (2011). A Guide to Historic Marietta, Ohio. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-276-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=73yRbdhAQ3gC&pg=PA72. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Weber, Caroline (2007). Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. Picador. ISBN 9780312427344.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary (1795). An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution and the Effect it Has Produced in Europe. St. Paul's.

Further reading

- Lasky, Kathryn (2000). The Royal Diaries: Marie Antoinette, Princess of Versailles: Austria-France, 1769. New York: Scholastic. ISBN 978-0-439-07666-1.

- Loomis, Stanley (1972). The Fatal Friendship: Marie Antoinette, Count Fersen and the flight to Varennes. London: Davis-Poynter. ISBN 978-0706700473.

- MacLeod, Margaret Anne (2008). There Were Three of Us in the Relationship: The Secret Letters of Marie Antoinette. Irvine, Scotland: Isaac MacDonald. ISBN 978-0-9559991-0-9.

- Naslund, Sena Jeter (2006). Abundance: A Novel of Marie Antoinette. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-082539-3.

- Romijn, André (2008). Vive Madame la Dauphine: A Biographical Novel. Ripon: Roman House. ISBN 978-0955410024.

- Thomas, Chantal (1999). The Wicked Queen: The Origins of the Myth of Marie-Antoinette. New York: Zone Books. ISBN 978-0-942299-40-3.

- Vidal, Elena Maria (1997). Trianon: A Novel of Royal France. Long Prairie, MN: Neumann Press. ISBN 978-0-911-84596-9.

- Zweig, Stefan (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3909-2.

External links

- "Marie Antionette" in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Story of Marie Antoinette with Primary Sources

- Find A Grave

- Marie Antoinette's official Versailles profile

- Using mtDNA to track the case of Louis XVII, son of Marie Antoinette

- Marie Antoinette Online – A site with a sympathetic bend, and contains a great deal of information.

- The marais of Marie-Antoinette sur parismarais.com

- Tea At Trianon – Many articles on all things Antoinette, from Versailles to Trianon to the most obscure details of life in Royal France, by historian and author Elena Maria Vidal.

"Marie Antoinette". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Marie Antoinette". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Online catalog of Marie Antoinette's personal reading library from the Petit-Trianon palace, based on 1863 printed catalog, online at LibraryThing.

- If they have no bread, let them eat cake.

Marie AntoinetteBorn: 2 November 1755 Died: 16 October 1793French royalty Vacant Title last held byMarie LeszczyńskaQueen consort of France and Navarre

10 May 1774 – 1 October 1791Herself

as Queen of the FrenchHerself

as Queen of FranceQueen consort of the French

1 October 1791 – 21 September 1792Vacant Title next held byJoséphine de Beauharnais

as Empress of the FrenchTitles in pretence Loss of title

— TITULAR —

Queen consort of France and Navarre/

Queen consort of the French