- Mesa Verde National Park

-

"Mesa Verde" redirects here. For other uses, see Mesa Verde (disambiguation).

Mesa Verde National Park IUCN Category II (National Park)

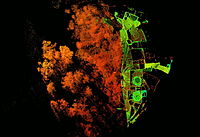

Cliff PalaceLocation Montezuma County, Colorado

United States

North AmericaNearest city Cortez Coordinates 37°11′02″N 108°29′19″W / 37.183784°N 108.488687°WCoordinates: 37°11′02″N 108°29′19″W / 37.183784°N 108.488687°W Area 52,121.93 acres (21,093.00 ha)

51,890.65 acres (20,999.40 ha) federalEstablished 1906-06-29 Visitors 557,248 (in 2006) Governing body National Park Service Type: Cultural Criteria: iii Designated: 1978 (2nd session) Reference #: 27 State Party:  United States

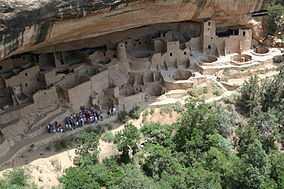

United StatesRegion: Europe and North America Designated: October 15, 1966 Reference #: 66000251 Mesa Verde National Park is a U.S. National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Montezuma County, Colorado, United States. It was created in 1906 to protect some of the best-preserved cliff dwellings in the world. The park occupies 81.4 square miles (211 km2) near the Four Corners and features numerous ruins of homes and villages built by the Ancestral Puebloan people, sometimes called the Anasazi. There you can find over 4,000 archaeological sites and over 600 cliff dwellings of the Pueblo people.

The Anasazi inhabited Mesa Verde between AD 550 to 1300. These people were mainly subsistence farmers; they grew crops on nearby mesas. Their primary crop was corn, which was also the major part of their diet. Men were also hunters, which further increased their food supply. The women of the Anasazi were famous for their elegant basket weaving. Anasazi pottery is just as famous as their baskets; their artifacts, even today, are highly prized. Since the Anasazi kept no written records, their artifacts are the only link to understanding their interesting culture.

By 750 AD, the people were building mesa-top villages made of adobe. By the late 12th century, they began to build the cliff dwellings for which Mesa Verde is famous.

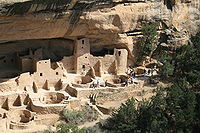

Mesa Verde is best known for cliff dwellings, which are structures built within caves and under outcropping in cliffs — including Cliff Palace, which is thought to be the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The Spanish term Mesa Verde translates into English as "green table".

Contents

Geography and climate

Mesa Verde National Park, with 52,000 acres, is located in the southwestern Colorado.[1][2]:220 Its canyons were created by erosion from receding ancient oceans and waterways, which resulted in Mesa Verde National Park elevations ranging from about 6,000 to 8,572 feet (1,800 to 2,613 m), the highest elevation at Park Point. The terrain in the park is now a transition zone between the low desert plateaus and the Rocky Mountains.[3]:9-13, 24

The climate is semi-arid. Water for farming and consumption by the Ancient Pueblo Peoples was provided by summer rains, winter snowfall and seeps and springs in and near the Mesa Verde villages. The middle mesa areas, 10 degrees cooler than on the mesa at 7,000 feet (2,100 m), were ideal for agriculture, and the lower temperatures reduced the amount of water needed for agriculture.[3]:15 The cliff dwellings were built with obvious attention to managing solar energy. In the winter, the angle of the sun warmed the masonry of the cliff dwellings, warm breezes blew from the valley, and the air was 10-20 degrees warmer in the canyon alcoves than on the top of the mesa. In the summer, the cliff dwellings, due to the angle of the sun, much of the village was protected from direct sunlight.[3]:16-17

History

Early people

Hunter-gather 8,000 B.P. to AD 1

- Evidence from the nearby Hovenweep National Monument indicates that there were Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers and people of the Archaic period as early as 8,000 years ago.[4][5] The ancestors of the Mesa Verde Pueblo people hunted and lived in a difficult terrain, traversed deep canyons and areas of few animals and limited vegetation, and managed limited access to water - which made life difficult and limited the size of their hunt groups. They gathered seeds and fruit from wild plants to supplement their diet.[3]:27

Basketmakers AD 1 to 550

- The people living in the Four Corners region were introduced to maize and basketry through Mesoamerican trading about 2,000 years Before Present Able to have greater control of their diet through cultivation, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle became more sedentary[3]:27 as small disperse groups began cultivating maize and squash. They also continued to hunt and gather wild plants.[6][3]:27-30

- They were named "Basketmakers" for their skill in making baskets for storing food, covering with pitch to heat water, and using to toast seeds and nuts. They wove bags, sandals, and belts out of yucca plants and leaves - and strung beads. They occasionally lived in dry caves where they dug pits that they lined with stones to store food.[3]:27-30 These people were ancestors of the Pueblo people of the Hovenweep Pueblo settlement[6] and Mesa Verde.[3]:27[7]:148

Mesa Verde residents

Modified Basketmakers AD 550 to 750

- This era resulted in the introduction of pottery, which reduced the number of baskets that they made and eliminated the creation of woven bags. The simple, gray pottery allowed them a better tool for cooking and storage. Beans were added to the cultivated diet. Bows and arrows made hunting easier, and thus the acquisition of hides for clothing. Turkey feathers were woven into blankets and robes. On the rim of Mesa Verde, small groups built pit houses several feet below the surface with elements suggestive of the introduction of celebration rituals.[3]:33-37

Developmental Pueblo AD 750 to 1100

- Pueblo buildings were built with stone, windows facing south, and in U, E and L shapes. The buildings were located more closely together and reflected deepening religious celebration. Towers were built near kivas and likely used for lookouts. Pottery became more versatile, including pitchers, ladles, bowls, jars and dishware for food and drink. White pottery with black designs emerged, the pigments coming from plants. Water management and conservation techniques, including the use of reservoirs and silt-retaining dams also emerged during this period.[3]:39-45

- Like the people at Hovenweep National Monument and Canyon de Chelly National Monument, about AD 1100, the Mesa Verde village communities moved from mesa tops to the heads of canyons.[7]:146

Great Pueblo period AD 1100 to 1300

Architecture

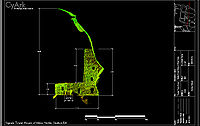

Section view of Kiva A in Mesa Verde's Fire Temple, cut from laser scan data collected by a CyArk/National Park Service partnership. Since Fire Temple was at least partially built to conform to the dimensions of the cliff alcove in which it was built, it is neither round in form nor truly subterranean like other structures generally defined as kivas.

Section view of Kiva A in Mesa Verde's Fire Temple, cut from laser scan data collected by a CyArk/National Park Service partnership. Since Fire Temple was at least partially built to conform to the dimensions of the cliff alcove in which it was built, it is neither round in form nor truly subterranean like other structures generally defined as kivas.

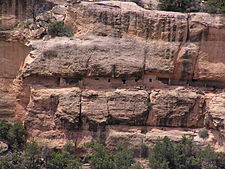

- Mesa Verde is best known for a large number of well-preserved cliff dwellings, houses built in shallow caves and under rock overhangs along the canyon walls. The structures contained within these alcoves were mostly blocks of hard sandstone, held together and plastered with adobe mortar. Specific constructions had many similarities but were generally unique in form due to the individual topography of different alcoves along the canyon walls. In marked contrast to earlier constructions and villages on top of the mesas, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde reflected a region-wide trend towards the aggregation of growing regional populations into close, highly defensible quarters during the AD 1200s.[3]:13, 47-59

- While much of the construction in these sites conforms to common Pueblo architectural forms, including kivas, towers, and pit-houses, the space constrictions of these alcoves necessitated what seems to have been a far denser concentration of their populations. Mug House, a typical cliff dwelling of the period, was home to around 100 people who shared 94 small rooms and eight kivas built right up against each other and sharing many of their walls; builders in these areas maximized space in any way they could, and no areas were considered off limits to construction.[8]

- Not all of the people in the region lived in cliff dwellings; many colonized the canyon rims and slopes in multi-family structures that grew to unprecedented size as populations swelled.[8] Decorative motifs for these sandstone/mortar constructions, both surface and cliff dwellings, included T-shaped windows and doors. This has been taken by some archaeologists, such as Stephen Lekson, as evidence of the continuing reach of the Chaco Canyon elite system, which had seemingly collapsed around a century before.[9] Other researchers see these motifs as part of a more generalized Puebloan style and/or spiritual significance, rather than evidence of a continuing specific elite socioeconomic system.[10]

Migration from Mesa Verde

- These construction and water-related activities lead archaeologists to speculate that climatic change and increased population placed the communities under stress. The ancient people of Mesa Verde left the area in the late 1200s, possibly in response to a 24-year regional drought.[3]:73-74[11]:133-137[nb 1] People in the entire Four Corners region were also abandoning smaller communities at that time, and the area may have been nearly empty by AD 1300.[2]:220[11]:156 Having left the Mesa Verde area, the people of Mesa Verde moved south to southern Arizona and New Mexico.[3]:74

- Since then, there is evidence of Native Americans hunting in the Mesa Verde area. There is no evidence, though, that anyone lived in the cliff dwellings or pueblos after the Ancient Puebloan people.[11]:9

Notable sites

Pueblo Photo Comments Balcony House

Set on a high ledge facing east, Balcony House with 45 rooms and 2 kivas, which would have been cold for its residents in the winter. The modern visitor enters by climbing a 32-foot ladder and a crawling through a 12-foot tunnel. The exit, a series of toe-holds in a cleft of the cliff, was believed to be the only entry and exit route for the cliff dwellers, which made the small village easy to defend. One log was dated at AD 1278 so it was likely built not long before the Mesa Verde people migrated out of the area.[3]:55-56[2]:225-226 It was offically excavated by Jesse Nusbaum, one of the first Superindents of Mesa Verde National Park, in 1910.[12] Visitors can enter Balcony House through ranger-guided tours.[13]

This photo is of an Emmett Harryson, a Navajo, at a T-shaped doorway at Balcony House (1929).Cliff Palace

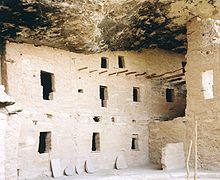

This multi-storied ruin, the largest and best-known of the cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde, is located in the largest cave in the center of the Great Mesa. It was south- and southwest-facing, providing greater warmth from the sun in the winter. The site had 217 rooms, including storage rooms, open courts, walkways, and 23 kivas. Dating back more than 700 years, the dwelling is constructed of sandstone, wooden beams, and mortar. [14] Many of the rooms were brightly painted.[11]:3, 29, 31, 37[3]:51 Long House

Located on the Wetherill Mesa, Long House is the second-largest village, for about 150 people. The location was excavated as part of the Wetherhill Mesa Archaeological Project during the years 1959 through 1961. [15]The 150 rooms are not clustered like the standard cliff dwellings, nor is it one of the most elegant set of buildings. Stones were used without shaping for fit and stability. Two overhead ledges contain more rooms. One ledge seems to include an overlook with small holes in the wall to see the rest of the village below. A spring is accessible within several hundred feet and seeps are located in the rear of the village.[3]:57 Mesa Verde Reservoirs These ancient reservoirs, built by the Ancient Puebloans,[3]:43 on September 26, 2004, became a National Civil Engineering Historic Landmark.[16] Mug House This ruin situated on Wetherill Mesa contains 94 rooms, a large kiva, and a nearby reservoir. It received its name from four mugs the Charles Mason and the Wetherill brothers found strung together on a string.[3]:59 This ceremonial structure has a keyhole shape, due to a recess behind the fireplace and a deflector, that is considered an element of the Mesa Verde style. The rooms clustered around the kiva formed part of the courtyard, indicating the kiva would have been roofed.[citation needed] Oak Tree House

Oak Tree House and neighboring Fire Temple can be visited via a 2 hour ranger-guided hike.[17] Spruce Tree House

Spruce Tree House is the third-largest village, within several hundred feet of a spring, and had 130 rooms and eight kivas. It was constructed sometime between AD 1211 and 1278. It is believed anywhere from 60 to 80 people lived there at one time. [18] Because of its protective location, it is well preserved.[19][3]:52 The short trail to Spruce House begins at the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum.[20] Square Tower House

The Square Tower House is one of the stops on the Mesa Top Loop Road diving tour.[20] The tower that gives this site its name is the tallest structure in Mesa Verde. This cliff dwelling was occupied between AD 1200 and 1300.[citation needed] Approximately 600 of the over 4700 archeological sites found in Mesa Verde National Park are cliff dwellings.[3]:7 In addition to the cliff dwellings, Mesa Verde boasts a number of mesa-top ruins.[2]:220-221 Examples open to public access include the Far View Complex and Cedar Tree Tower on Chapin Mesa, and Badger House Community, on Wetherill Mesa.[2]:222

Discovery

Ute

The area in and around Mesa Verde had been home to the Utes. In 1868, a treaty between the United States government and the Ute tribe recognized Ute ownership of Colorado land by identifying land west of the Continental Divide as Ute land. After there had become an interest in land in western Colorado, a new treaty in 1873 left the Ute with a strip of land in southwestern Colorado between the border with New Mexico and 15 miles north. Most of Mesa Verde lies within this strip of land. The Ute wintered in the warm, deep canyons and found sanctuary there and the high plateaus of Mesa Verde. Believing the cliff dwellings to be sacred ancestral sites, they did not live in the ancient dwellings.[3]:77

Spanish explorers

Mexican-Spanish missionaries and explorers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, seeking a route from Santa Fe to California, faithfully recorded their travels in 1776. They reached the Mesa Verde (green plateau) region, which they named after its high, tree-covered plateaus, but they never got close enough, or into the needed angle, to see the ancient stone villages.[3]:77[11]:9-10 They were the first white men to travel the route through much of the Colorado Plateau into Utah and back through Arizona to New Mexico.[21]

1870s and 1880s American visitors

- Occasional trappers and prospectors visited, with one prospector, John Moss, making his observations known in 1873.[22]

- The following year, he led eminent photographer William Henry Jackson through Mancos Canyon, at the base of Mesa Verde. There, Jackson both photographed and publicized a typical stone cliff dwelling.[22]

- In 1875, geologist William H. Holmes retraced Jackson's route.[22]

- Reports by both Jackson and Holmes were included in the 1876 report of the Hayden Survey, one of the four federally financed efforts to explore the American West. These and other publications led to proposals to study Southwestern archaeological sites systematically.[22]

- Virginia McClurg, a journalist for the New York Daily Graphic, visited Mesa Verde in 1882 and 1885 in her quest to find Ancient Pueblo settlements. In 1885, her party found Echo Cliff House, Three Tier House and Balcony House, and these findings induced her future work to protect the dwellings and artifacts.[3]:78[23]:61-72

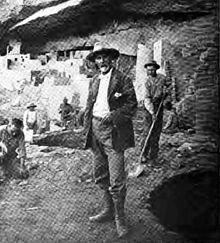

- A family of cattle ranchers, the Wetherills, befriended members of the Ute tribe near their ranch southwest of Mancos, Colorado. With the Ute tribe's approval, the Wetherills were allowed to bring cattle into the lower, warmer plateaus of the present Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in the winter. Word had spread of the dwellings of Ancient Pueblo people. Acowitz, a member of the Ute tribe, told the Wetherills of a special dwelling in Mesa Verde: "Deep in that canyon and near its head are many houses of the old people - the Ancient Ones. One of those houses, high, high in the rocks, is bigger than all the others. Utes never go there, it is a sacred place."[3]:79[11]:17-18 On December 18, 1888, Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason, cowboys from Mancos, found Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde after spotting the ruins from the top of the mesa. Wetherill gave the ruin its current name. Richard Wetherill, family and friends explored the ruins and gathered artifacts, some of which they sold to the Historical Society of Colorado and much of which they kept.[3]:79-80[11]:17-24

- Among the people who stayed with the Wetherills and explored the cliff dwellings was mountaineer, photographer, and author Frederick H. Chapin, who visited the region during 1889 and 1890. He described the landscape and ruins in an 1890 article and later in an 1892 book, The Land of the Cliff-Dwellers, which he illustrated with hand-drawn maps and personal photographs.[23]:63

Gustaf Nordenskiöld

The Wetherills also hosted Gustaf Nordenskiöld, the son of polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, in 1891.[3]:81[11]:27 Nordenskiöld was a trained mineralogist who introduced scientific methods to artifact collection, recorded locations, photographed extensively, diagrammed sites, and correlated what he observed with existing archaeological literature as well as the home-grown expertise of the Wetherills.[1] He removed a lot of artifacts and sent them to Sweden, where they eventually went to the National Museum of Finland. Nordenskiöld published, in 1893, The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde.[3]:82-84 When Nordenskiöld shipped the collection that he made of Mesa Verde artifacts, the event initiated concerns about the need to protect Mesa Verde land and its resources.[3]:83-84

National Park

Events leading to Mesa Verde becoming a National Park

Virginia McClurg was diligent in her efforts between 1887 and 1906 to inform the United States and European community of the importance of protecting the important historical material and dwellings in Mesa Verde. Her efforts included enlisting support from 250,000 women through the Federation of Womens Clubs, writing and having published poems in popular magazines, giving speeches domestically and internationally, and forming the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association. The Colorado Cliff Dwellers' purpose was to protect the resources of Colorado cliff dwellings, reclaiming as much of the original artifacts as possible and sharing information about the people who dwelt there. A fellow activist for protection of Mesa Verde and prehistoric archaeological sites included Lucy Peabody, who, located in Washington, D.C., met with members of Congress to further the cause.[1][23]:61-72[3]:85

Former Mesa Verde National Park superintendent Robert Heyder communicated his belief that the park might have been far more significant with the hundreds of artifacts taken by Nordenskiöld.[24]

By the end of the 19th century, it was clear that Mesa Verde needed protection from people in general who came to Mesa Verde and created or sold their own collection of artifacts. In a report to the Secretary of the Interior, Smithsonian Institute Ethnologist J. Walter Fewkes described vandalism at Mesa Verde's Cliff Palace:

- Parties of "curio seekers" camped on the ruin for several winters, and it is reported that many hundred specimens there have been carried down the mesa and sold to private individuals. Some of these objects are now in museums, but many are forever lost to science. In order to secure this valuable archaeological material, walls were broken down [...] often simply to let light into the darker rooms; floors were invariably opened and buried kivas mutilated. To facilitate this work and get rid of the dust, great openings were broken through the five walls which form the front of the ruin. Beams were used for firewood to so great an extent that not a single roof now remains. This work of destruction, added to that resulting from erosion due to rain, left Cliff Palace in a sad condition.[25]

Mesa Verde National Park

Some key occurrences are:

- 1906 - President Teddy Roosevelt approved creation of the Mesa Verde National Park and the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906.[3]:84-85 The park was named with the Spanish term for green table because of its forests of juniper and piñon trees.[26]

- 1908-1922 - The Spruce Tree House, Cliff Palace and Sun Temple ruins were stabilized.[2]:221 Most of the early efforts were led by J. Walter Fewkes.[27]

- 1930s-1940s - Civilian Conservation Corps workers, starting in 1932, performed important efforts for excavations, trails and roads, museum exhibits and buildings at Mesa Verde.[27]

- 1958-1965 - Wetherill Mesa Archeological Project included archaeological excavations, stabilization of sites, and surveys.

With excavation and study of eleven Wetherill Mesa sites, it is considered the largest archaeological effort in the United States.[27]

- 1966 - As with all historical areas administered by the National Park Service, the park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[28]

- 1978 - It was designated a World Heritage Site in 1978.[27]

- 1987 - The Mesa Verde Administrative District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[28].

- 1996, 2000 (twice), 2001, 2002, and 2003 - The park, which is covered with pinyon pine and Utah juniper forests, suffered from a large number of wildland fires.[29]

Park services

Mesa Verde's park entrance is on U.S. Hwy 160, about 9 miles (15 kilometers) east of the community of Cortez and about 7 miles west of Mancos, Colorado.[30]

The park protects over 4,000 archaeological sites, including 600 separate cliff dwellings.[citation needed]

The Far View visitor center is 15 miles (24 kilometers) from the entrance, and Chapin Mesa (the most popular area) is another 6 miles (10 kilometers) beyond the visitor center.[31]

Park facilities and access:[31]

- The park's Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum is open all year.

- Three of the cliff dwellings on Chapin Mesa are open to the public.

-

- Spruce Tree House is open all year, weather permitting.

- Balcony House, Long House and Cliff Palace require tour tickets for ranger-guided tours. Many other dwellings are visible from the road but not open to tourists.

- The park offers hiking trails, a campground, and, during peak season, facilities for food, fuel, and lodging; these are unavailable in the winter.

The Mesa Verde National Park Post Office has the ZIP Code 81330.[32]

Neighboring Ute Mountain Tribal Park

The Ute Mountain Tribal Park, adjoining Mesa Verde National Park to the east of the mountains, is approximately 125,000 acres of land along the Mancos River. Hundreds of surface sites, cliff dwellings, petroglyphs and wall paintings of Ancestral Puebloan and Ute cultures are preserved in the park. Native American Ute tour guides provide background information about the people, culture and history who lived in the park lands. National Geographic Traveler chose it as one of "80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century", one of only nine places selected in the United States.[33]

Colorado Historical Society grant: culturally modified trees

In February 2008, the Colorado Historical Society decided to invest a part of its US$7 million budget into a culturally modified trees project in the National Park.[34]

Gallery

More Mesa Verde images

-

Round tower, Cliff Palace. Photo by Ansel Adams, 1941

Laser Scans

-

Plan of entire Spruce Tree House from above, cut from a laser scan

-

Laser scan section of the four-story Square Tower House

See also

Mesa Verde

- Mesa Verde Wilderness

- Ute Mountain Tribal Park in Mesa Verde

- Yucca House National Monument administered by the Mesa Verde National Park

Other neighboring Ancient Pueblo sites in Colorado

- Anasazi Heritage Center

- Canyons of the Ancients National Monument

- Crow Canyon Archaeological Center

- Hovenweep National Monument

Other cultures in the Four Corners region

- Trail of the Ancients

- List of ancient dwellings of Pueblo peoples

Early American cultures

- List of prehistoric sites in Colorado

- Ancient Pueblo Peoples

- Oasisamerica cultures

- Paleo-Indians

Notes

- Notes

- ^ Wenger states that the drought occurred from AD 1273 to 1285, but the drought is generally referred to as a 23-24 year drought, as stated by Watson.

- Citations

- ^ a b c FitzGerald, Michael C.. The Majesty of Mesa Verde, Wall Street Journal, 2009 March 13, p. W12.

- ^ a b c d e f Casey, Robert L. (1993) [1983]. High Journey to the Southwest. The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 1-56440-151-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Wenger, Gilbert R. (1991) [1980]. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Park, Colorado: Mesa Verde Museum Association. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ^ Hovenweep Visitor Guide, National Park Service. Retrieved 9-20-2011.

- ^ Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998) Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. p. 377. ISBN 0-8153-0725X.

- ^ a b History & Culture. National Park Service. Retrieved 9-20-2011.

- ^ a b Rohn, Arthur H.; Ferguson, William M. (2006). Puebloan ruins of the Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3969-7.

- ^ a b Kantner, John. (2004) Ancient Puebloan Southwest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 161-66. ISBN 9780521788809.

- ^ Lekson, Stephen. (1999). The Chaco Meridian: centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press. pp. 158, 175-180.

- ^ Phillips, David A., Jr., 2000, "The Chaco Meridian: A skeptical analysis" paper presented to the 65th annual meeting of the Society of American Archaeology, Philadelphia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Watson, Don. Indians of the Mesa Verde. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado: Mesa Verde Museum Association. ISBN 0-937062-00-6.

- ^ "Mesa Verde Balcony House". Aramark: Parks and Destinations. http://www.visitmesaverde.com/discover/points-of-interest/cliff-dwellings/balcony-house.aspx. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Balcony House." Mesa Verde National Park. Retrieved 9-21-2011.

- ^ Cliff House Mesa Verde National Park Points of Interest. Retrieved 10-16-2011.

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/meve/historyculture/cd_long_house.htm

- ^ Beard, Valerie. November 2004 Newsletter. American Society of Civil Engineer. Retrieved 9-23-2011.

- ^ New 2011 Backcountry Hikes. National Park Service. Retrieved 9-24-2011.

- ^ "Mesa Verde National Park: Spruce Tree House"

- ^ Spruce Tree House. Mesa Verde National Park. Retrieved 9-21-2011.

- ^ a b Self-Guided Tours: Chapin Mesa. Mesa Verde National Park. Retrieved 9-21-2011.

- ^ Katieri Treimer, Site research report, site no. 916, Southwest Colorado, Earth Metrics Inc. and SRI International for Contel Systems and the U.S. Air Force 1989

- ^ a b c d Reynolds, Judith; Reynolds, David. (2006). Nordenskiöld of Mesa Verde. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 1425704840.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Janet. (2003) [1990]. The Magnificent Mountain Women: Adventures in the Colorado. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3892-4.

- ^ Webb, Robert H.; Boyer, Diane E.; Turner, Raymond M. Repeat Photography: Methods and Applications in the Natural Sciences. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. p. 302. ISBN 1-59726-712-0.

- ^ United States Department of the Interior, pp. 486-487, 503.

- ^ "Mesa Verde National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved 9-24-2011.

- ^ a b c d Mesa Verde Park Timeline. National Park Service, Retrieved 9-24-2011.

- ^ a b National Register of Historic Places, Montezuma County, Colorado.] National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 9-24-2011.

- ^ Mesa Verde Fire History. Mesa Verde National Park. Retrieved 9-24-2011.

- ^ Mesa Verde Trip Planner. Mesa Verde National Park. pp.1-2. Retrieved 9-22-2011.

- ^ a b Mesa Verde Trip Planner. Mesa Verde National Park. Retrieved 9-22-2011.

- ^ ZIP Code Lookup United States Postal Service. Retrieved 1-2-2007.

- ^ Ute Mountain Tribal Park. Ute Mountain Tribal Park. Retrieved 6-18-2011.

- ^ State Historical Fund awards more than $7M in grants, Denver Business Journal, 2-14-2008.

Further reading

- Richard West Sellars, A Very Large Array: Early Federal Historic Preservation--The Antiquities Act, Mesa Verde, and the National Park Service Act (background and legislative history) published by the University of New Mexico School of Law, 2007.

- Fewkes, J. Walter for the United States Department of the Interior. (1910). Reports of the Department of the Interior - 1909 - Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Noble, David Grant. (1995). Ancient Ruins of the Southwest. Flagstaff, Arizona: Northland Publishing. ISBN 0-87358-530-5

- Nordenskiöld, Gustaf. (1893). Ruiner af Klippboningar I Mesa Verde's Cañons. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner.

- Nordenskiöld, Gustaf. (1893) The Cliff Dwellings of the Mesa Verde, Chicago: P.A. Norstedt & Söner.

- Oppelt, Norman T. (1989) Guide to Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest. Boulder, Colorado: Pruett Publishing. ISBN 0-87108-783-9.

External links

- Mesa Verde National Park. National Park Service.

- Mesa Verde National Park. Parks.com.

- Mesa Verde Digital Media Archive. (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data on Spruce Tree House, Fire Temple, and Square Tower House from a National Park Service/CyArk research partnership

- Mesa Verde National Park travel guide from Wikitravel.

- Mesa Verde National. City of Durango.

National parks of the United States Acadia • American Samoa • Arches • Badlands • Big Bend • Biscayne • Black Canyon of the Gunnison • Bryce Canyon • Canyonlands • Capitol Reef • Carlsbad Caverns • Channel Islands • Congaree • Crater Lake • Cuyahoga Valley • Death Valley • Denali • Dry Tortugas • Everglades • Gates of the Arctic • Glacier • Glacier Bay • Grand Canyon • Grand Teton • Great Basin • Great Sand Dunes • Great Smoky Mountains • Guadalupe Mountains • Haleakalā • Hawaiʻi Volcanoes • Hot Springs • Isle Royale • Joshua Tree • Katmai • Kenai Fjords • Kings Canyon • Kobuk Valley • Lake Clark • Lassen Volcanic • Mammoth Cave • Mesa Verde • Mount Rainier • North Cascades • Olympic • Petrified Forest • Redwood • Rocky Mountain • Saguaro • Sequoia • Shenandoah • Theodore Roosevelt • Virgin Islands • Voyageurs • Wind Cave • Wrangell-St. Elias • Yellowstone • Yosemite • ZionList of National Parks of the United States (by elevation) World Heritage Sites in the United States Northeast Midwest South West Carlsbad Caverns · Chaco Culture · Grand Canyon · Hawaii Volcanoes · Kluane-Wrangell-St. Elias-Glacier Bay-Tatshenshini-Alsek1 · Mesa Verde · Olympic National Park · Pueblo de Taos · Papahānaumokuākea · Redwood · Waterton Glacier International Peace Park1 · Yellowstone · Yosemite

Territories 1 Shared with Canada Protected Areas of the State of Colorado Federal National ParksNational MonumentsNational Recreation AreasNational Historic SitesNational Historic TrailsOld Spanish Trail · Pony Express Trail · Santa Fe TrailNational Scenic TrailContinental Divide TrailArapaho · Grand Mesa · Gunnison · Pike · Rio Grande · Roosevelt · Routt · San Isabel · San Juan · Uncompahgre · White RiverNational WildernessBlack Canyon of the Gunnison · Black Ridge Canyons · Buffalo Peaks · Byers Peak · Cache La Poudre · Collegiate Peaks · Comanche Peak · Dominguez · Eagles Nest · Flat Tops · Fossil Ridge · Great Sand Dunes · Greenhorn Mountain · Gunnison Gorge · Holy Cross · Hunter-Fryingpan · Indian Peaks · James Peak · La Garita · Lizard Head · Lost Creek · Maroon Bells-Snowmass · Mesa Verde · Mount Evans · Mount Massive · Mount Sneffels · Mount Zirkel · Neota · Never Summer · Platte River · Powderhorn · Ptarmigan Peak · Raggeds · Rawah · Sangre de Cristo · Sarvis Creek · South San Juan · Spanish Peaks · Uncompahgre · Vasquez Peak · Weminuche · West ElkNational Conservation AreasGunnison Gorge · McInnis CanyonsNational Wildlife RefugesAlamosa · Arapaho · Baca · Browns Park · Monte Vista · Rocky Flats · Rocky Mountain Arsenal · Two PondsState Arkansas Headwaters · Barr Lake · Bonny Lake · Boyd Lake · Castlewood Canyon · Chatfield · Cherry Creek · Cheyenne Mountain · Crawford · Eldorado Canyon · Eleven Mile · Golden Gate Canyon · Harvey Gap · Highline Lake · Jackson Lake · James M. Robb - Colorado River · John Martin Reservoir · Lake Pueblo · Lathrop · Lone Mesa · Lory · Mancos · Mueller · Navajo · North Sterling · Paonia · Pearl Lake · Ridgway · Rifle Falls · Rifle Gap · Roxborough · San Luis · Spinney Mountain · St. Vrain · Stagecoach · State Forest · Staunton · Steamboat Lake · Sweitzer Lake · Sylvan Lake · Trinidad Lake · Vega · Yampa RiverByers-Evans House · Colorado History Museum · El Pueblo · Fort Garland · Fort Vasquez · Georgetown Loop · Healy House Museum and Dexter Cabin · Pearce-McAllister Cottage · Pike Stockade · Trinidad History Museum · Ute Indian MuseumOther Beaver Meadows · Burlington Carousel · Black Hawk · Central City · Colorado Chautauqua · Cripple Creek · Durango-Silverton Railroad · Georgetown · Granada · Leadville · Lindenmeier Site · Lowry Ruin · Mesa Verde · Pikes Peak · Pike's Stockade · Raton Pass · Shenandoah-Dives Mill · Silver Plume · Silverton · Telluride · U.S. Air Force Academy Cadet AreaGarden of the Gods · Garden Park Fossil Area · Indian Springs Trace Fossil · Lost Creek Scenic Area · Morrison Fossil Area · Raton Mesa · Roxborough Park · Russell Lakes · Sand Creek · Slumgullion Earthflow · Spanish Peaks · Summit LakeAmerican Discovery Trail · Colorado Trail · Continental Divide Trail · Great Divide Trail · Kokopelli's Trail · Paradox Trail · Tabeguache TrailAlpine Loop · Cache la Poudre-North Park · Colorado River Headwaters · Dinosaur Diamond · Flat Tops · Frontier Pathways · Gold Belt · Grand Mesa · Guanella Pass · Highway of Legends · Lariat Loop · Los Caminos Antiguos · Mount Evans · Pawnee Pioneer · Peak to Peak · San Juan Skyway · Santa Fe Trail · Silver Thread · South Platte River Trail · Top of the Rockies · Trail of the Ancients · Trail Ridge · Unaweep/Tabeguache · West Elk LoopColorado Department of Natural Resources (web) U.S. National Register of Historic Places Topics Lists by states Alabama • Alaska • Arizona • Arkansas • California • Colorado • Connecticut • Delaware • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Maine • Maryland • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • Nevada • New Hampshire • New Jersey • New Mexico • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Ohio • Oklahoma • Oregon • Pennsylvania • Rhode Island • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas • Utah • Vermont • Virginia • Washington • West Virginia • Wisconsin • WyomingLists by territories Lists by associated states Other  Category:National Register of Historic Places •

Category:National Register of Historic Places •  Portal:National Register of Historic Places

Portal:National Register of Historic PlacesUnited States Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Arizona - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Colorado - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in New Mexico - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Utah - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Texas - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in NevadaMexico Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Chihuahua - Ancient Pueblo dwellings in Sonora - Huápoca - Cuarenta CasasAfrica Asia Categories:- IUCN Category II

- Mesa Verde National Park

- Native American history of Colorado

- Native American museums in Colorado

- Museums in Montezuma County, Colorado

- Archaeology museums in Colorado

- Protected areas established in 1906

- Protected areas of Montezuma County, Colorado

- Ancient Puebloan archaeological sites in Colorado

- Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad

- Historic districts in Colorado

- Landmarks in Colorado

- Pre-historic cities in the United States

- Native American archeology

- Oasisamerica cultures

- Puebloan peoples

- Ruins in the United States

- National parks in Colorado

- National Register of Historic Places in Colorado

- World Heritage Sites in the United States

- Cliff dwellings

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.