- Oasisamerica

-

Oasisamerica was a broad cultural area in pre-Columbian southwestern North America. It extended from modern-day Utah down to southern Chihuahua, and from the coast on the Gulf of California eastward to the Río Bravo river valley. Its name comes from its position in relationship with the similar regions of Mesoamerica and nomadic Aridoamerica.[1]

As opposed to their nomadic Aridoamerican neighbors, the Oasisamericans were primarily an agricultural society.[2] Yet the climate did not permit very efficient cultivation as in Mesoamerica, and so they often resorted to hunting and gathering to meet their dietary needs.

Contents

Geography

The term "Oasisamerica" is derived from a combination of the terms oasis and America. It refers to a wild land dominated by the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Madre Occidental. To the east and west of these enormous mountain ranges stretch the grand arid plains of the Sonora, Chihuahua, and Arizona Deserts. At its height, Oasisamerica covered part of the present-day Mexican states of Chihuahua, Sonora and Baja California, as well as the U.S. states of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, and California.[3]

Despite being a basically dry land, Oasisamerica is scored by several bodies of running water like the Yaqui, Bravo, Colorado, and Gila Rivers. The presence of these rivers (and even some lakes that have since been swallowed by the desert), combined with a climate that was much milder that eastern Aridoamerica, allowed the development of agricultural techniques that were imported from Mesoamerica.

Characteristics of the Oasisamerican cultures

Cultural development

The story of the origins of the cultural superarea of Mesoamerica takes place some 2000 years after the separation of Mesoamerica and Aridoamerica. Some of the Aridoamerican communities farmed as a complement to their hunter-gatherer economy. Those communities, among whom one finds adherents to the Desert Tradition, later would become more truly agricultural and form Oasisamerica.[4] The process of introducing agriculture in the desert-like land of northern Mexico and the southern United States was gradual and extensive: by the year 600 AD (a time which coincides with the twilight of Teotihuacan), several groups had already acquired agricultural techniques.

Based on maize remnants found in Bat Cave, Arizona, it appears that agriculture practices date back to at least 3500 BC. Given that the oldest traces of maize in North America date back to the year 5000 BC, it would seem that the hypothesis of importation of agriculture from the south is correct. It is less certain who brought the agricultural technology and what role they played in the development of the high cultures of Oasisamerica.

A pebble of turquoise, one of the principal trade goods of the Oasisamericans.

A pebble of turquoise, one of the principal trade goods of the Oasisamericans.

At least three hypotheses have been proposed to explain the birth of the cultures of Oasisamerica. One, an endogenous model, posits an independent cultural development whose roots lie deep in antiquity. From this point of view, thanks to a superior climate (a relatively arbitrary assertion since the climatic difference between Oasisamerica and Aridoamerica is not pronounced), the ancient desert communities would have been able to develop agriculture much as the Mesoamericans did.

A second hypothesis presupposes that the nomads of the Mesoamerican culture slowly moved northward over time. Thus, the Oasisamericans would be an offshoot of their neighbors to the south. In this view, the development of the Oasisamerican cultures, much like the northern Mesoamerican cultures, began with a group of outsiders who where closely tied to the local original inhabitants of western Mexico. Archaeological evidence indicates that yuto-nahuan groups brought agriculture to Oasisamerica. Even if agricultural techniques were imported from the south, the Oasisamerican communities developed their own distinct characteristics that bore many similarities to the agricultural traditions of Middle America.

There are many indications of a close relationship between the two great cultural regions of North America. For one, the turquoise that the Mesoamericans prized so dearly came almost exclusively from southern New Mexico and Arizona. Demand for this mineral alone may have played a large part in establishing trade relationships between the two cultural areas. At the same time, in Paquimé, a site connected to the Mogollon culture, there have been found ceremonial structures related to Mesoamerican religion, like the juego de pelota, and an important number of skeletons of guacamayas that were carefully transported from the forests of southeastern Mexico.

Cultural areas

The area encompassed by Oasisamerica fostered the growth of three great cultures: the Anasazi, the Hohokam, and the Mogollon, all of which existed among other surrounding cultures including the Fremont and Patayan.[5]

Anasazi

Main article: Ancient Pueblo PeoplesThe Anasazi culture flourished in the region currently known as the Four Corners.[6] The territory was covered by juniper forests which the ancient peoples learned to exploit for their own needs, since foraging among the other vegetation only sufficed for half of the year, only to fail from November to April. The Anasazi society is one of the most complex to be found in Oasisamerica, and they are assumed to be the ancestors of the modern Pueblo people (including the Zuñi and Hopi). (The word "Anasazi" is a Navajo term meaning "enemy ancestors"; its neutrality should thus not be blindly assumed.)

The Anasazi is considered to be the most intensely studied Pre-Columbian culture in the United States.[7] Archaeological investigation has established a sequence of cultural development that began before the first century BC. and extended to 1540 AD when the Pueblo Indians were subjugated by the Spanish Crown. This long period encompasses the Basketmaker I, II, and III phases followed by the Pueblo I, II, III, and IV phases. The Basketmaker I phase, beginning before the first century BC, marks the transition of the Anasazi from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary agricultural lifestyle based on the cultivation of maize (introduced to the region around 750 BC). In the Basketmaker II phase, the Anasazi took up residence in caves and rocky shelters, and in Basketmaker III Era (500-750 AD) they constructed the first subterranean cities with up to four abodes in a circular arrangement.

The Pueblo period begins with the development of ceramics. The most prominent feature of these ceramics is the predominance of pieces of a white or red color with black designs. During the Pueblo I phase (750-900 AD), the Anasazi developed their first irrigation systems, and their former subterranean habitations were slowly replaced by houses constructed of masonry. Pueblo II (900-1150) is defined by the construction of great works of architecture, including multi-family, multi-story dwellings. The following phase of Pueblo III (1150–1350) witnessed the greatest expansion of Anasazi agriculture as well as the construction of large regional communication networks that would persist until the Pueblo IV Era. In Pueblo IV (1350–1600), much of the earlier society disintegrated along with the communication networks. Cities were abandoned, and many of the region's inhabitants returned to an economy based on hunting and gathering.

A Hopi woman dressing the hair of an unmarried girl in her tribe.

A Hopi woman dressing the hair of an unmarried girl in her tribe.

The reasons underpinning the decline of the Anasazi remain somewhat of a mystery. The phenomenon is thought to be associated with a prolonged drought that befell the region from 1276 to 1299. The time after this great drought and until the arrival of the Spaniards in Arizona is almost completely unknown. When the Europeans arrived at the Anasazi region, it was populated by the Pueblo Indians, a group without a unified ethnicity. The Zuñi had no apparent relatives; the Hopi spoke an Uto-aztecan language; the Tewas and Tiwas were Tanoanos and the Navajo were Athabaskans. It is not known how the last group arrived in the mix, only that they were a group of hunters who originally came from Canada and eventually were assimilated into the larger culture of the Oasisamericans.

The religion of the Pueblo Indians was based upon the worship of plant-like deities and the fertility of the earth. They believed that supernatural beings called the kachina had come to the surface of the earth from the sipapu (center of the earth) at the moment of the creation of the human race. Worship in Pueblo societies was organized by secret all-male groups that met in kivas. The members of these secret societies claimed to represent the kachina.

Hohokam

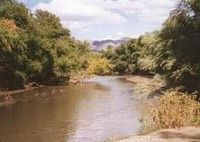

The Gila River was vitally important in the development of the Hohokam culture.

The Gila River was vitally important in the development of the Hohokam culture. Main article: Hohokam

Main article: HohokamIn contrast to their Anasazi neighbors to the north, the nomadic communities of the Hohokam culture are poorly understood. They occupied the desert-like lands of Arizona and Sonora. The Hohokam territory is bounded by two large rivers, the Colorado and Gila Rivers, that outline the heart of the Sonora Desert. The surrounding ecosystem presented many challenges to agriculture and human life because of its high temperatures and scant rainfall. Due to these factors, the Hohokam were forced to construct irrigation systems with elaborate webs of reservoirs and canals for the Salt and Gila rivers that could reach several meters in depth and 10 km in length. Thanks to these canals, the Hohokam harvested as many as two crops of corn annually, which nicely complemented their other crops of pitaya and mezquite, from which they obtained flour, honey, alcohol, and wood.

The principal settlements of the Hohokam culture were Snaketown, Casa Grande, Red Mountain, and Pueblo de los Muertos, all of which are to be found in modern-day Arizona. A slightly different branch of the Hohokam people is known as the Trincheras, named after their most well-known site in the Sonora Desert. The Hohokam lived in small communities of several hundred people. Their lifestyle was very similar to that of the Anasazi in their Basketmaker III phase: semisubterranean but with spacious interiors. Hohokam ceramics are distinguished from those of their Anasazi and Mogollon neighbors by the predominance of a bluish color with red decorations. Several other artifacts are unique to the Hohokam, including conch necklaces (imported from the coastal regions of Greater California and Sonora) etched with acids produced by pitaya fermentation; and axes, trowels, and other stone instruments.

Archaeologists dispute the origins and ethnic identity of the Hohokam culture. Some hold that the culture developed endogenously (without outside influence), pointing to Snaketown which had its origins in the fourth century BC. Others believe the culture to be a product of migration from Mesoamerica. In defense of this line of thought, proponents point to the fact that Hohokam ceramics appeared in 300 BC. (also the time of Snaketown's founding), and that before this time, there was no indication of an independent regional development of ceramics. Along the same line of reasoning, several other technological advances like the canal works and certain cultural phenomena like cremation seem to have originated in western Mesoamerica.

The development of the Hohokam culture is divided into four periods: Pioneer (300 BC - 550 AD), Colonial (550-900 AD), Sedentary (900-1100 AD), and Classical (1100-1450 AD). The Pioneer period commenced with the construction of the canal works, and the Hohokam constructed semisubterranean dwellings in order to protect themselves from the blistering heat of the Sonoran Desert. In the Colonial period, ties were strengthened with Mesoamerica. Proof of this can be found in the recovery of copper bells, pyrite mirrors, and the construction of sports fields for playing juego de pelota, all of which display a very Hohokam touch. The relations with Mesoamerica and the presence of such traded goods indicate that by the Colonial period the Hohokam had already become organized into chiefdoms and centers of power. Relations with Mesoamerica would diminish in the following period, and the Hohokam turned to construct multi-story buildings like Casa Grande, which had four levels.

By the time the Europeans arrived in the Arizona and Sonora Deserts, a region which they named Pimería Alta, the urban centers of the Hohokam had already become abandoned presumably due to the health and ecological disasters that befell the indigenous social system. The inhabitants of the region were called Pápagos, a group which spoke an Uto-Aztecan language. This community had an economy based on foraging and incipient agriculture on mountain slopes. They were a semi-nomadic people, probably because they had to migrate in order to compensate for the scarcity of food resources in the foothills of the mountains they called home.

Mogollon

The Mogollon Mountains in southeastern New Mexico.

The Mogollon Mountains in southeastern New Mexico. Main article: Mogollon culture

Main article: Mogollon cultureThe Mogollon was a cultural area of Mesoamerica that extended from the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental, northward to Arizona and New Mexico in the southwestern United States. Some scholars prefer to distinguish between two broad cultural traditions in this area: the Mogollon itself and the Paquime culture that was derived from it. Either way, the peoples who inhabited the area in question adapted well to a landscape that was marked by the presence of pine forests and steep mountains and ravines.

In contrast to their Hohokam and Anasazi neighbors to the north, the Mogollons usually buried their dead. The culture's graves often included ceramic art and semiprecious stones. Because the Mogollon burial sites displayed such wealth, they were often looted by grave robbers who sought to sell their spoils on the archaeological black market.

Perhaps the most impressive Mogollon ceramic tradition was to be found in the valley of the Mimbres River in New Mexico. The ceramic production of this region became most developed between the eighth and twelfth centuries. It was characterized by white pieces decorated with stylized representations of daily life in the community that created them. This was a very exceptional approach in a cultural area whose pottery was otherwise dominated by geometric patterns.

As another contrast with the Hohkam and Anasazi, there is no widely-accepted chronology for the development of the Mogollon culture. The scholars Alfredo López Austin and Leonardo López Luján, for their historical analysis of the region, borrowed a chronology proposed earlier by Paul Martin, who himself divided Mogollon history into two general periods; the "Early" period runs from 500 BC. until 1000 AD, and the "Late" period begins in the eleventh and goes to the sixteenth century.

The first period featured a more or less slow cultural development. Technological changes were produced very gradually, and the form of social relationships and organizational patterns remained almost static for 1500 years. During the Early period, the Mogollons lived in rocky dwellings from which they defended themselves from the incursions of their hunter neighbors. Much like the Hohokam and Anasazi, the Mogollon also lived in semisubterranean abodes that often featured a kiva.

In the eleventh century, the population in the Mogollon area multiplied much more rapidly than it had in the preceding centuries. It is probably that in this period, the area benefited from trade relations with Mesoamerica, a fact that facilitated the development of agriculture and the stratification of society. It is also possible that Anasazi influence could have grown at this time, because the Mogollon began to construct buildings of masonry, just like their northern neighbors.

The Mogollon culture reached its height in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. At this time, the culture's major centers grew in population, size, and power. Paquime, in Chihuahua, was perhaps the largest of those. It dominated a mountainous region that contains many archaeological sites known as casas alcantilado, outposts constructed in hard-to-reach caves on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madre. Paquime traded with the heart of Mesoamerica, to which it provided precious minerals like turquoise and cinnabar. It also controlled the trade of certain products from the coasts of the Gulf of California, especially its Nassarius conch shells. Paquime received heavy influence from the Mesoamerican societies, as evidenced by the presence of arenas for the Mesoamerican ballgame and the remains of animals native to tropical Central America like the macaw.

The decline of the main centers of Mogollon power began in the thirteenth century, even before the apex of Paquime. By the fifteenth century, a large part of the region had become abandoned by its former inhabitants. Some of the groups that had been associated with the Paquime culture sought refuge in the Sierra Madre, while others fled to the north where they combined with the Anasazi. The people of the Mimbres River emigrated and eventually settled in present-day Coahuila. It is supposed that the Taracahitas (including the Yaquis, Mayos, Opatas, and Tarahumaras) that currently live in northeastern Mexico are descendants of the Mogollones.

Fremont

Main article: Fremont cultureThe Fremont area covered a large part of modern-day Utah. It was situated to the north of the Anasazi cultural area. Its cultural development as a part of Oasisamerica took place between the fifth and fourteenth centuries. Scholars contend that the Fremont culture was derived from the Anasazi culture. Theoretically, the Freemont communities would have emigrated toward the north, bringing with them the customs, social organization structures, and technology of the Anasazi. This hypothesis neatly explains the presence of ceramics in Utah that are very similar to those found in Mesa Verde.

A second hypothesis suggests that the Fremont culture may have been derived from buffalo-hunting societies, probably from a culture of Atapascan origin. As time passed, the foreign culture would have adopted the culture of their southern neighbors. In both this theory and the aforementioned, there is a justification for the less-complex development in Fremont as opposed to other regions of Oasisamerica because of their more suitable climates for agriculture.

The decay of the Fremont culture began as early as the second half of the tenth century and was completed in the fourteenth. Upon the Spaniards' arrival, the region was occupied by the Shoshones, an Uto-Aztecan group.

Pataya

Main article: PatayanThe Patayan area occupies the western part of Oasisamerica. It comprises the modern-day states of California and Arizona in the U.S., and Baja California and Sonora in Mexico. The Patayans were a peripheral culture whose cultural development was probably influenced by their Hohokam neighbors to the east. From them they would have learned the Mesoamerican ballgame, cremation techniques, and techniques for the production of ceramics. Some scholars argue that the coastal region around the Gulf of California (within the Patayan area) was occupied by another, separate culture called the Trincheras. Their name is taken from the nearby site found in the Sonora Desert.

The Patayan culture began to disappear in the fourteenth century. When the Spanish arrived in the region, the Colorado River Valley was only occupied by the river-dwelling Yuman or rieños.

See also

- Aridoamerica

- History of Mesoamerica (Paleo-Indian)

- Mesa Grande

- Mesoamerica

- Paleo-Indians

- Prehistoric Southwestern Cultural Divisions

- List of dwellings of Pueblo peoples

References

- ^ Mexico's Indigenous Past, By Alfredo López Austin, Leonardo López Luján, Bernard R. Ortiz De Montellano

- ^ Culture e religioni indigene in America centrale e meridionale, By Lawrence Eugene Sullivan

- ^ The essence of anthropology, by William A. Haviland, Harald E. L. Prins, Dana Walrath, Bunny McBride

- ^ Mexico's Indigenous Past, By Alfredo López Austin, Leonardo López Luján, Bernard R. Ortiz De Montellano

- ^ Archaeology of prehistoric native America: an encyclopedia, By Guy E. Gibbon, Kenneth M. Ames

- ^ World Regional Geography By Joseph J. Hobbs, Andrew Dolan

- ^ Case studies in environmental archaeology, by Elizabeth Jean Reitz, C. Margaret Scarry, Sylvia J. Scudder

- This article draws heavily on the 31 May 2006 version of the corresponding article in the Spanish-language Wikipedia.

Categories:- Archaeological cultures of North America

- Archaeological sites in Chihuahua

- Formative period in the Americas

- History of indigenous peoples of North America

- Native American history

- Native American history of Arizona

- Native American history of Colorado

- Native American history of New Mexico

- Native American history of Utah

- Oasisamerica cultures

- Pre-Columbian cultural areas

- Puebloan peoples

- Southwest tribes

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.